Abstract

Background

Huge efforts are being made to control the spread and impacts of the coronavirus pandemic using vaccines. However, willingness to be vaccinated depends on factors beyond the availability of vaccines. The aim of this study was three-folded: to assess children’s rates of COVID-19 Vaccination as reported by parents, to explore parents’ attitudes towards children’s COVID-19 vaccination, and to examine the factors associated with parents’ hesitancy towards children’s vaccination in several countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR).

Methods

This study utilized a cross-sectional descriptive design. A sample of 3744 parents from eight countries, namely, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia (KSA), and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), was conveniently approached and surveyed using Google forms from November to December 2021. The participants have responded to a 42-item questionnaire pertaining to socio-demographics, children vaccination status, knowledge about COVID-19 vaccines, and attitudes towards vaccinating children and the vaccine itself. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS- IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to analyze the data. A cross-tabulation analysis using the chi-square test was employed to assess significant differences between categorical variables and a backward Wald stepwise binary logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the independent effect of each factor after controlling for potential confounders.

Results

The prevalence of vaccinated children against COVID-19 was 32% as reported by the parents. Concerning parents’ attitudes towards vaccines safety, about one third of participants (32.5%) believe that all vaccines are not safe. In the regression analysis, children’s vaccination was significantly correlated with parents’ age, education, occupation, parents’ previous COVID-19 infection, and their vaccination status. Participants aged ≥50 years and those aged 40-50 years had an odds ratio of 17.9 (OR = 17.9, CI: 11.16-28.97) and 13.2 (OR = 13.2, CI: 8.42-20.88); respectively, for vaccinating their children compared to those aged 18-29 years. Parents who had COVID-19 vaccine were about five folds more likely to vaccinate their children compared with parents who did not receive the vaccine (OR = 4.9, CI: 3.12-7.70). The prevalence of children’s vaccination in the participating Arab countries is still not promising.

Conclusion

To encourage parents, vaccinate their children against COVID-19, Arab governments should strategize accordingly. Reassurance of the efficacy and effectiveness of the vaccine should target the general population using educational campaigns, social media, and official TV and radio channels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19) was announced as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) in January 2020, with 5.5 million deaths reported until January 2022 [1]. Most countries, around the World, have witnessed large numbers of cases despite the precautions taken [2]. For instance, the total number of the reported COVID-19 cases has exceeded 10% of the total population in 115 countries [3]. This, in turn, have led to severe impact including psychological burden [4, 5]. Efficacious vaccine is an essential tool in the fight against the current COVID-19 pandemic to achieve collective immunity, which can help reduce transmission, hospitalizations, and intensive care utilization, as well as prevent additional mortality [6]. An up-to-date Italian study found that COVID-19 vaccines can prevent approximately 17% of expected cases, 32% of hospitalizations, 29% of admissions to intensive care units, and 38% of deaths [7].

Several COVID-19 vaccines are now available for public. However, major issues have been identified to affect vaccine coverage, including limited manufacturing capacity, global inequality in the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, and most importantly vaccine hesitancy which could represent a major challenge in the global efforts to control the pandemic [8, 9]. Vaccine hesitancy refers to a delay in accepting or refusing vaccination despite its availability [10].

Many studies around the world have reported hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccine among the public and this was reflected in a systematic review involved 31 studies published in 2020 [11]. One-third of participants in a study from four African and Middle Eastern countries were hesitant about getting vaccinated against the COVID-19 [12]. Similarly, another multi-country study showed that around one-third of respondents from Bangladesh and India, and around one-quadrant of respondents from Pakistan and Nepal are hesitant about getting vaccinated against the COVID-19 [13]. Likewise, a Japanese study showed that approximately one-third of respondents are hesitant about getting vaccinated against the COVID-19 [14]. Arab countries also reported similar trends in COVID-19 hesitancy [15,16,17]. Certainly, individuals who are hesitant in getting vaccinated query the usefulness and safety of vaccines for their children [18]. In Italy, a cross-sectional study was conducted to evaluate the knowledge, attitude, and intention to vaccinate children < 18 years. They found that 41.2% of families of children ≥12 years and 36.1% among families of children < 12 years would not vaccinate their children [18]. Perceived vaccine safety and efficacy and perceived risk of transmission of infection to adults were the two determinants of intention to vaccinate for both age groups [18].

Many factors influence vaccination decisions, including trust in the government and health care professionals, social influences, high levels of knowledge about the vaccine, and general positive attitudes toward vaccines [19]. Another study found that parents with different levels of education and employment status had significant differences in vaccine knowledge and awareness; similarly, these two factors also significantly influenced parental vaccine hesitancy [20]. The knowledge score of parents was inversely correlated with vaccine hesitancy and moderately associated with their awareness score [20].

In a study conducted in Poland regarding children vaccination, the main concerns expressed by parents were the possibility of adverse effects, the lack of adequate testing of the preparations in children, and the fear of future complications [21]. Therefore, the COVID-19 vaccine must have proven safety and efficacy in preventing complications as well as transmission to ensure vaccination of children [22].

In the Arab countries, like Jordan, commitment to precaution measures against COVID-19 virus such as hand washing, wearing a face mask, and social distancing is not optimal [23]. Figures of the vaccinated population against COVID-19 in Arab countries, including children, are still not promising. To our knowledge, no studies have been conducted in these countries to assess the attitudes of parents towards children vaccination against COVID-19 infection. At the same time, official data on the rates of vaccinated children in the participating countries are lacking despite its availability since Arab countries were first to approve Chinese COVID-19 vaccine [24]. The aims of this study were to (1) assess the parents’ self-reported coverage of children’s vaccination against COVID-19, (2) assess parents’ attitudes toward children’s vaccination, and (3) study factors associated with vaccination’s status and hesitancy of parents towards children’s vaccination in several Arab countries. It is important to stress the point that all the countries involved in our study had almost similar response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including lockdowns, quarantine, as well as non-pharmaceutical interventions including physical distancing, public face masking, hand hygiene, and practicing respiratory etiquette. Additionally, these countries made huge efforts to make COVID-19 vaccines available in their respective communities.

Methods and materials

Study setting, design, and participants

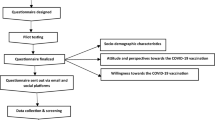

Our study was conducted in eight countries located in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR), namely: Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia (KSA), and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). A descriptive questionnaire-based cross-sectional online survey was employed in this study focusing on married individuals having children (parents). A convenience sample was approached through social media platforms. A questionnaire was firstly developed in English, then it was translated into Arabic (the native language of our respondents) by two bilingual specialists. The questionnaire was then uploaded to Google Form® and disseminated to those who could access the online survey. The inclusion criteria included being a citizen of any participating country, aged 18 or older, married and having children, reading, and understanding Arabic, and being willing to fill the online questionnaire. The google form led participants who were single or not having children to submit their responses at early stage and their responses were excluded. An online link of the questionnaire, along with an introductory letter about the study, was sent to participants via media platforms like Facebook®, WhatsApp®, Twitter®, and email addresses, for a period of four weeks; 15-November- 13-December 2021. In addition, respondents were asked to share the questionnaire link with their relatives, friends, and social networks.

Study instrument

The authors reviewed the available literature and developed a 42-item questionnaire composed of three main sections (Supplementary File). The first section consisted of 12 questions on participants’ socio-demographic characteristics such as age, gender, marital status, having children, education, nature of work or study, and country of residence. The second section comprised four questions that solicited general knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine. The third section of the questionnaire consisted of 26 items and inquired about participants’ attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination of their children and the vaccine itself.

Survey development

Two researchers checked the content of the questionnaire and its face validity before the final approval. To ensure its reliability, the questionnaire was pilot tested with the first 40 responses. Based on these responses and the feedback, refinements were made. The Cronbach’s alpha score was found to be 0.81. The responses of the pilot-testing were excluded from the final analysis.

Ethical considerations

All participants have given their informed consent through reading the following statement and ticking a box next to it: “Completing the questionnaire would be considered consent to voluntary participation”. Participants were informed that the study would not disclose any personal information and that their data would be stored under high-security settings with only the research team having access to these data.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS- IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to analyze the data. Categorical variables were reported as frequency counts and percentages. A cross-tabulation analysis using the chi-square test was employed to assess significant differences between categorical variables. Finally, all statistically significant factors revealed from the cross-tabulation analysis were subjected to a backward Wald stepwise binary logistic regression analysis to assess the independent effect of each factor after controlling for potential confounders. A P value < 0.05 was set for statistical significance.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

A total of 3744 participants with valid responses were involved in the final analysis. More than half of the sample (55.5%) was females (n = 2078) and 44.5% (n = 1666) was males. About 40% of the study population have been diagnosed with COVID-19 infection and the majority (83%, n = 3108) have been vaccinated against the infection. The socio-demographic characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1.

Prevalence of children vaccination against COVID-19 and parents’ beliefs about COVID-19 vaccine safety

Table 2 shows the number of children, their age, and beliefs of the study population towards the COVID-19 vaccine for children. About one-third of the sample (32.5%) reported that all COVID-19 vaccines are not safe and close percentage reported that their children received the vaccine (31.9%, n = 1194). Also, Fig. 1 shows children’s vaccination prevalence per country.

The relationship between participants’ socio-demographic characteristics and vaccination status of their children

To assess the impact of socio-demographic characteristics on the vaccination against COVID-19 among children, a cross-tabulation analysis was performed. This analysis revealed that all participant’s socio-demographic factors were associated with vaccination status of their children. These factors included: participant’s gender (p = 0.037), participant’s education (p < 0.001), work or study field (p < 0.001), participant’s age (p < 0.001), number of children (p < 0.001), children age (p < 0.001), if the parent had a COVID-19 before (p < 0.001), and if the parent received a COVID-19 vaccine (p < 0.001).

As shown in Table 3, parents whose work or study was health-related showed a higher tendency for not vaccinating their children compared to others. Moreover, willingness to vaccinate increased with an increased parents’ age. Remarkably, less than 4% of parents whose children were younger than 12 years have vaccinated their children.

As seen in Table 3, parents who have been vaccinated against COVID-19 and those who intend to get the vaccine in the future were more likely to have vaccinated children. With respect to the country of residence and perceived necessity for COVID-19 vaccine with vaccination status among children, parents living in KSA, UAE, Kuwait, and Iraq were more willing to vaccinate their children compared to parents from Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Qatar. Furthermore, parents who believed that the vaccine is necessary for individuals younger than 18 years were more willing to vaccinate their children than those who didn’t have the same belief. Table 4 illustrates these associations.

Parents’ attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccine according to children’s vaccination status

Table 5 presents parents’ attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccine according to children’s vaccination status. All attitudes’ items had significant statistical associations with vaccination status (p ≤ 0.05). About half of parents who believed that COVID-19 vaccines are safe for children had vaccinated their offspring compared to only about 20% of parents who did not have the same belief (P < 0.001). In addition, parents who were against children’s vaccines due to the unknown long-term side effects of the vaccine (P < 0.001) or perceived a lack of scientific research about the effects of the vaccine on children (P < 0.001) were less likely to vaccinate their children. Most importantly, willingness to vaccinate children decreased among parents who think that the vaccine may change human genes (P < 0.001).

Regression analysis of factors associated with increased chance of having vaccinated children

In the binary regression analysis, the vaccination status was categorized into two main levels; (Yes) and (No). Children’s vaccination was significantly correlated with parents’ age, education, occupation, parents’ previous COVID-19 infection, and their vaccination status. Participants aged ≥50 years and those aged 40-50 years had an OR of 18 (OR = 17.9, CI: 11.16-28.97) and 13 (OR = 13.2, CI: 8.42-20.88) for vaccinating their children compared to those aged 18-29 years. Significantly, parents who had COVID-19 vaccine were five folds more likely to vaccinate their children compared with parents who didn’t receive the vaccine (OR = 4.9, CI: 3.12-7.70). Table 6 presents the results of the binary logistic regression analysis.

Discussion

Prevalence of children vaccination against COVID-19 and parents’ beliefs about COVID-19 vaccine safety

Globally, there is a dearth of literature regarding the vaccine coverage amongst children and most published studies have assessed the parents’ willingness or intention to vaccinate children rather than true vaccination status. The preliminary finding of this study shows that most of the parents in the Arab countries are hesitant to vaccinate their children. This hesitancy can be explained by the lack of information about vaccine safety [25], concerns about vaccine effectiveness [26]. However, this finding might be different from other studies conducted in different countries. For example, results from a previous study in the Singapore population showed much higher willingness of parents to vaccinate their children aged between 12 and 18 years [26]. The variance between our study and the Singaporean study can be explained by differences in culture and society. Despite the majority of the parents have been already vaccinated against COVID-19, most of them didn’t vaccinate their children against COVID-19. This finding cannot be isolated from the other finding which demonstrated that one third of the participants believe that all vaccines are not safe.

The relationship between parents’ socio-demographic characteristics and vaccination status of their children

Several significant correlations between children’s vaccination status and participants’ sociodemographic characteristics were found in this study. For instance, older parents showed extreme higher readiness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 than younger counterparts. This result is congruent with a previous study which found that parents younger than 40 are more hesitant to vaccinate children [27]. However, this finding mismatches a previous study which showed that parents younger than 35 in Latin American countries are less likely to be hesitant to vaccinate children [28]. In terms of children’s number, parents with three or more children were more willing to vaccinate them than their counterparts. Participants of children aged between 12 and 17 years were more ready to vaccinate them than their counterparts. Our findings might be explained by the fact that younger parents usually have younger children (less than 12 years). Despite its approval, vaccination of the children younger than 12 years is still questionable among public.

In terms of caretaker’s gender, fathers showed a higher tendency towards vaccinating their kids than mothers. This result is consistent with a previous study from Lebanon [16] and US [29]. However, the result was different from a previous study in Poland which showed that mothers are more enthusiastic to vaccinate children than fathers [21]. This may be explained by the difference in the social role of fathers or mothers between communities.

Interestingly, parents whose work or study was health-related showed a lower tendency towards vaccinating their children than parents working in non-health-related fields. This finding could mean means that healthcare workers are concerned about safety, not convinced about efficacy, and worried about side effects. This result is consistent with a previous study stated that fewer caregivers plan to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 [30]. Also, parents with a lower educational level showed higher readiness towards vaccinating their children than parents with a higher educational level. This finding is consistent with a previous study which showed that undergraduate parents are more enthusiastic to vaccinate children than parents with higher education [12, 28, 31]. This finding is also congruent with previous studies which concluded that parents’ educational level is one of the determinants of willingness to vaccinate children [20, 32].

Parents who haven’t been infected with COVID-19 were more eager to vaccinate their children than other participants. This finding can be explained by their carefulness from being infected with COVID-19. Another explanation to this result may refer to the fear of the vaccine’s side effects perceived by those who have already got the infection before as the side effects can be similar to symptoms of the infection itself. This result is supported by previous studies. For example, a study showed that parents who are anxious from COVID-19 are keener to vaccinate children [31]. Another study showed that the perceived danger of being infected with COVID-19 is one of the determinants for parents’ willingness to vaccinate children [18]. Additionally, another research found that the readiness to get the COVID-19 vaccine increases with a higher perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 [33]. Vaccinated parents and those who intend to get the vaccine in the future were more willing to vaccinate their children than unvaccinated parents and those who do not intend to get the vaccine. The reason behind this difference can be explained by awareness of vaccinated parents about the COVID-19 vaccines which is supported by an earlier study [31].

Results of the current study showed that parents who had received COVID-19 vaccine or those who intend to get the vaccine are more likely to vaccinate their children. These results are consistent with results from another study stated that the likelihood of child vaccination was greater among parents who had already received or were likely to receive a COVID-19 vaccine [34].

Parents’ attitudes towards vaccinating their children against COVID-19

This study showed that parents’ attitudes towards vaccinating children are significantly associated with their children’s vaccination status. For example, almost half of parents who believe that COVID-19 vaccines are safe on children had vaccinated their children. This result is similar to the rates found in a previous scoping review [32]. On the other hand, only one-fifth of parents who don’t trust safety of COVID-19 vaccines on children had vaccinated their children.

This study demonstrated that parents who were against children vaccination because of the unknown long-term side effects of the vaccine were less willing to vaccinate their children. This finding matches a previous research which found that one of the main parents’ concerns is the possible future complications of the vaccine [21]. Similarly, parents who think that the vaccine may change human genes were less eager to vaccinate their children. These findings were consistent with a previous study which showed that vaccination concerns determine parents’ willingness to vaccinate children against COVID-19 [26]. These results are consistent with results from Palestine which reported that adequate information about vaccines and their risk–benefit ratios are important to build trust and favorable attitudes towards vaccines [17].

It is worthy to mention that the willingness towards vaccinating children is significantly different depending on the country of residence. For instance, parents from KSA, UAE, Kuwait, and Iraq were more enthusiastic to vaccinate their children than those from Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Qatar. A previous study has shown high rates of vaccine hesitancy in Jordan and Kuwait [35]. A probable cause of vaccination hesitancy may be also linked to misleading information shared on media platforms. This explanation was addressed in a previous study done on adolescents and parents of adolescents in the USA which showed that social media negatively impacted the opinions of adolescents and parents on COVID-19 vaccination [36].

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of our study lies in the relatively large sample selected from eight middle eastern countries. This type of multi-country study gives importance to the results and overcomes the bias that might result from cultural, economic, or social varieties. However, the authors recognize that our cross-sectional design and convenient sample could impact statistical conclusions and the generalizability of the findings. Another limitation is the lack of precise data about the COVID-19 vaccines’ availability for children in the studied countries. Such data would address the role of vaccines’ availability in vaccinating children against the COVID-19. Although our results, collected via social media yielded a similar male-to-female ratio in the Arab world, the decisional autonomy in relation to children’s vaccination might refer finally to fathers. Additionally, there are many assumptions and findings in our study that can be fully understood, addressed, and explored with qualitative research which uses smaller information-rich samples and asks open questions to get a holistic picture about the factors that impact children vaccination against COVID-19. Moreover, our study reported the parents’ self-reported coverage of children vaccination against COVID-19, therefore, the method of ascertaining vaccination status of all children in the household could be affected by recall bias. Finally, other factors could impact COVID-19 vaccine uptake among children, including availability of vaccines, awareness of recommendations, access or convenience of the services and their booking systems. As these factors were not measured in our present study, it is complicated to infer what the largest barriers to uptake are.

Recommendations

Face-to-face information or educational interventions should be used to help parents understand why vaccines are important; explain where, how, and when to access service and respond to hesitations and concerns about vaccine safety or effectiveness. Such interventions are interactive and can be tailored to target specific populations or identified barriers. Concise and clear vaccine information should be provided in multiple languages to improve vaccine confidence. Targeted campaigns should be implemented for parents that are socioeconomically disadvantaged and less educated.

Conclusion

The parents’ self-reported coverage of children vaccination against COVID-19 in Arab countries seems to be much lower than those in other countries such as Singapore. Moreover, parents in the studied countries are still hesitant to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19. This hesitancy could be led by certain parents’ socio-demographic characteristics, contracting COVID-19 infection before, and their vaccination status. To increase COVID-19 vaccination rates in the countries located in the EMR, it is essential to address variables connected to parents’ hesitancy to vaccinate children.

Availability of data and materials

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (MK).

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus Disease-2019

- EMR:

-

Eastern Mediterranean Region

- KSA:

-

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- OR:

-

Odd Ratio

- PHEIC:

-

Public Health Emergency of International Concern

- UAE:

-

United Arab Emirates

References

Johns Hopkins University Center. COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins; 2022.

Khatatbeh M. The Battle Against COVID-19 in Jordan: From Extreme Victory to Extreme Burden. Front Public Health. 2021;8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.634022.

Worldometer COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Available at: https://www.worldometers.info/corona; Accessed 19 June 2022.

Khatatbeh M, Alhalaiqa F, Khasawneh A, Al-tammemi AB, Khatatbeh H, Alhassoun S, et al. The Experiences of Nurses and Physicians Caring for COVID-19 Patients : Findings from an Exploratory Phenomenological Study in a High Case-Load Country. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179002.

Khatatbeh M, Khasawneh A, Hussein H, Altahat O, Alhalaiqa F. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic Among the General Population in Jordan. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.618993.

Hodgson SH, Mansatta K, Mallett G, Harris V, Emary KRW, Pollard AJ. What defines an efficacious COVID-19 vaccine? A review of the challenges assessing the clinical efficacy of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:e26–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30773-8.

Sacco C, Mateo-Urdiales A, Petrone D, Spuri M, Fabiani M, Vescio MF, et al. Estimating averted COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, intensive care unit admissions and deaths by COVID-19 vaccination, Italy, january−september 2021. Eurosurveillance. 2021;26. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.47.2101001.

Al-Tammemi AB, Tarhini Z. Beyond equity: Advocating theory-based health promotion in parallel with COVID-19 mass vaccination campaigns. Public Heal Pract. 2021;2:100142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhip.2021.100142.

Neumann-Böhme S, Varghese NE, Sabat I, Barros PP, Brouwer W, van Exel J, et al. Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21:977–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-020-01208-6.

MacDonald NE, Eskola J, Liang X, Chaudhuri M, Dube E, Gellin B, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33:4161–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036.

Sallam M. Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: A concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines. 2021;9:160. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9020160.

Faezi NA, Gholizadeh P, Sanogo M, Oumarou A, Mohamed MN, Cissoko Y, et al. Peoples’ attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine, acceptance, and social trust among African and Middle East countries. Health Promot Perspect. 2021;11:171–8. https://doi.org/10.34172/hpp.2021.21.

Hawlader MDH, Rahman ML, Nazir A, Ara T, Haque MMA, Saha S, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in South Asia: a multi-country study. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;114:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.09.056.

Machida M, Nakamura I, Kojima T, Saito R, Nakaya T, Hanibuchi T, et al. Acceptance of a covid-19 vaccine in japan during the covid-19 pandemic. Vaccines. 2021;9:210. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9030210.

Alduwayghiri EM, Khan N. Acceptance and Attitude toward COVID-19 Vaccination among the Public in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-sectional Study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2021;22:730–4. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10024-3114.

Kasrine Al Halabi C, Obeid S, Sacre H, Akel M, Hallit R, Salameh P, et al. Attitudes of Lebanese adults regarding COVID-19 vaccination. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10902-w.

Kateeb E, Danadneh M, Pokorná A, Klugarová J, Abdulqader H, Klugar M, et al. Predictors of willingness to receive covid-19 vaccine: Cross-sectional study of palestinian dental students. Vaccines. 2021;9:954. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9090954.

Russo L, Croci I, Campagna I, Pandolfi E, Villani A, Reale A, et al. Intention of Parents to Immunize Children against SARS-CoV-2 in Italy. Vaccines. 2021;9:1469.

Smith LE, Amlôt R, Weinman J, Yiend J, Rubin GJ. A systematic review of factors affecting vaccine uptake in young children. Vaccine. 2017;35:6059–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.046.

Voo JYH, Lean QY, Ming LC, Hanafiah NHM, Al-Worafi YM, Ibrahim B. Vaccine knowledge, awareness and hesitancy: A cross sectional survey among parents residing at sandakan district, sabah. Vaccines. 2021;9:1348. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9111348.

Babicki M, Pokorna-Kałwak D, Doniec Z, Mastalerz-Migas A. Attitudes of parents with regard to vaccination of children against covid-19 in Poland. A nationwide online survey. Vaccines. 2021;9:1192. https://doi.org/10.3390/VACCINES9101192.

Eberhardt CS, Siegrist CA. Is there a role for childhood vaccination against COVID-19? Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2021;32:9–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/pai.13401.

Khatatbeh M, Al-Maqableh HO, Albalas S, Al Ajlouni S, A’aqoulah A, Khatatbeh H, et al. Attitudes and Commitment Toward Precautionary Measures Against COVID-19 Amongst the Jordanian Population: A Large-Scale Cross-Sectional Survey. Front Public Health. 2021;9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.745149.

Cyranoski D. Arab nations first to approve Chinese COVID vaccine - despite lack of public data. Nature. 2020;588:548. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03563-z.

Altulaihi BA, Alaboodi T, Alharbi KG, Alajmi MS, Alkanhal H, Alshehri A. Perception of Parents Towards COVID-19 Vaccine for Children in Saudi Population. Cureus. 2021. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.18342.

Griva K, Tan KYK, Chan FHF, Periakaruppan R, Ong BWL, Soh ASE, et al. Evaluating Rates and Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy for Adults and Children in the Singapore Population: Strengthening Our Community’s Resilience against Threats from Emerging Infections (SOCRATEs) Cohort. Vaccines. 2021;9:1415. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9121415.

Zona S, Partesotti S, Bergomi A, Rosafio C, Antodaro F, Esposito S. Anti-COVID vaccination for adolescents: A survey on determinants of vaccine parental hesitancy. Vaccines. 2021;9:1309. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9111309.

Urrunaga-Pastor D, Herrera-Añazco P, Uyen-Cateriano A, Toro-Huamanchumo CJ, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Hernandez AV, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with parents’ non-intention to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 in Latin America and the Caribbean. Vaccines. 2021;9:1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9111303.

Litaker JR, Tamez N, Bray CL, Durkalski W, Taylor R. Sociodemographic Factors Associated with Vaccine Hesitancy in Central Texas Immediately Prior to COVID-19 Vaccine Availability. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:368.

Goldman RD, Krupik D, Ali S, Mater A, Hall JE, Bone JN, et al. Caregiver willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 after adult vaccine approval. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:10224. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910224.

Bono SA, Siau CS, Chen WS, Low WY, Faria E, Villela DM, et al. Adults ’ Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccine for Children in Selected Lower- and Middle-Income Countries. Vaccines. 2022;10:11.

Pan F, Zhao H, Nicholas S, Maitland E, Liu R, Hou Q. Parents’ Decisions to Vaccinate Children against COVID-19 : A Scoping Review. Vaccines. 2021;9:1476.

Patwary MM, Bardhan M, Disha AS, Hasan M, Haque MZ, Sultana R, et al. Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among the Adult Population of Bangladesh Using the Health Belief Model and the Theory of Planned Behavior Model. Vaccines. 2021;9:1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9121393.

Szilagyi PG, Shah MD, Delgado JR, Thomas K, Vizueta N, Cui Y, et al. Parents’ intentions and perceptions about COVID-19 vaccination for their children: Results from a national survey. Pediatrics. 2021;148. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-052335.

Sallam M, Dababseh D, Eid H, Al-Mahzoum K, Al-Haidar A, Taim D, et al. High rates of covid-19 vaccine hesitancy and its association with conspiracy beliefs: A study in jordan and kuwait among other arab countries. Vaccines. 2021;9:42. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9010042.

Middleman AB, Klein J, Quinn J. Vaccine Hesitancy in the Time of COVID-19 : Attitudes and Intentions of Teens and Parents Regarding the COVID-19 Vaccine. Vaccines. 2022;10:4. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10010004.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants in this survey.

Funding

This research project did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: MK, HK, ABA, WM, AA.; Methodology: MK, HK, ABA, AA; Validation, MS; Formal analysis: MK.; Investigation: all authors; Data curation: all authors; Writing—original draft preparation: MK, HK, ABA, ZT; Writing—review and editing: all authors; Visualization: MK.; Supervision: MK, AA, ABA; Project administration: MK, M-AM. All authors have read and approved to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol of this study was reviewed and approved by Yarmouk University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) Committee (IRB/2021/47). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Written Informed consent (electronically) was obtained from all participants. Participation in this study was voluntary. Informed consent was ensured by the presence of an introductory section in the survey used in this study, with the submission of responses implying an agreement to participate.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Khatatbeh, M., Albalas, S., Khatatbeh, H. et al. Children’s rates of COVID-19 vaccination as reported by parents, vaccine hesitancy, and determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among children: a multi-country study from the Eastern Mediterranean Region. BMC Public Health 22, 1375 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13798-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13798-2