Abstract

Background

Review studies increasingly emphasize the importance of the role of parenting in interventions for preventing overweight in children. The aim of this study was to examine typologies regarding how consistently parents apply energy-balance related behavior rules, and the association between these typologies and socio-demographic characteristics, energy balance-related behaviors among school age children, and the prevalence of being overweight.

Methods

For this cross-sectional study, we had access to a database managed by a Municipal Health Service Department in the Netherlands. In total, 4,865 parents with children 4–12 years of age participated in this survey and completed a standardized questionnaire. Parents classified their consistency of applying rules as “strict”, “indulgent”, or “no rules”. Typologies were identified using latent class analyses. We used regression analyses to examine how the typologies differed with respect to the covariates socio-demographic characteristics, children’s energy balance-related behaviors, and weight status.

Results

We identified four stable, distinct parental typologies with respect to applying dietary and sedentary behavior rules. Overall, we found that parents who apply “overall strict EBRB rules” had the highest level of education and that their children practiced healthier behaviors compared to the children of parents in the other three classes. In addition, we found that parents who apply “indulgent dietary rules and no sedentary rules” had the lowest level of education and the highest percentage of non-Caucasians; in addition, their children 8–12 years of age had the highest likelihood of being overweight compared to children of parents with “no dietary rules”.

Conclusions

Parents’ consistency in applying rules regarding dietary and sedentary behaviors was associated with parents’ level of education and ethnic background, as well as with children’s dietary and sedentary behaviors and their likelihood of becoming overweight. Our results may contribute to helping make healthcare professionals aware that children of parents who do not apply sedentary behavior rules are more likely to become overweight, as well as the importance of encouraging parents to apply strict dietary and sedentary behavior rules. These results can serve as a starting point for developing effective strategies to prevent overweight among children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Childhood overweight and obesity are a major public health concern worldwide [1, 2], particularly among children in low socio-economic status (SES) families. Moreover, in the Netherlands, being overweight and obese is most prevalent among children of Turkish or Moroccan descent [3,4,5]. Addressing this increasing problem and preventing overweight are important because overweight and obesity is typically rather difficult to treat [6] and because of their far reaching (social) health consequences that can develop in childhood and/or adulthood [7,8,9]. A high number of children have unhealthy energy-balance-related behaviors (EBRBs), including low consumption of fruit and/or vegetables, high intake of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), and amounts of excessive screen time. [10,11,12,13]. Moreover, over the long term unhealthy EBRBs can result in children becoming overweight or obese. In addition, review studies show that a high-fiber diet, for example a diet containing high amounts of fruits and vegetables consumption, and regular physical activity (PA) have been shown to be protective against becoming overweight and obese [3, 5].

Improvement of the EBRBs can contribute to the prevention of childhood obesity, but requires understanding of the factors determining children’s EBRBs. Parents play an essential role in the development of their child’s EBRBs by facilitating, promoting, and modeling EBRBs in their child's microenvironment, and by dealing with various environmental factors that contribute to the risk of overweight or obesity [14, 15]. Several reviews emphasize the importance of parenting in developing healthy EBRBs and helping prevent childhood overweight and obesity [16,17,18,19]. In addition, improving parenting skills (both general parenting styles and specific EBRB practices) can increase the efficacy of interventions designed to prevent overweight or obesity in children [17, 20]. Examples of healthy EBRBs in school age children include the daily consumption of breakfast, eating fruits and vegetables, drinking fewer than two glasses of SSBs a day, engaging in less than two hours of screen time a day, and playing outside for at least one hour a day [21,22,23].

In addition to the moderating role that general parenting styles play in EBRBs [24,25,26,27,28], establishing specific parental EBRB rules can have a positive effect on the child’s healthy dietary and physical activity behaviors while reducing the child’s television watching and unhealthy dietary behaviors [29, 30]. Furthermore, research show that unhealthy behaviors are more common among children of parents who do not apply EBRB rules. For example, absence of rules regarding watching television is associated with an average of > 2 h of television watching per day [31]. Thus, establishing and applying EBRB rules seems to be important steps for preventing the child from developing a positive energy balance state, which can lead to overweight. Therefore, it is important to involve parents in interventions and to emphasize the importance of applying EBRB rules. In addition, regarding the likelihood of a child becoming overweight, Leech reviewed studies to identify clustering patterns (typologies) of diet, PA and sedentary behavior among children or adolescents and their associations with socio-demographic indicators, and overweight and obesity. He found that obesogenic EBRBs cluster among school-age children in complex ways, that are both conducive and deleterious to good health, and thereby might have a cumulative effect on the development of overweight [32]. Because EBRBs seem to cluster, we hypothesized that this clustering phenomenon might also apply to EBRB rules established by parents. This may have implications for public health because understanding which EBRB rules need to be targeted simultaneously is useful to assist in the development of overweight prevention initiatives.

To increase our understanding of the effect of parental EBRB rules on the likelihood of a school age child becoming overweight, our aim was to examine: i) typologies regarding the degree of consistency with respect to applying parental EBRB rules across dietary and sedentary behavioral domains; ii) the association between these typologies and socio-demographic characteristics; iii) the association between these typologies and healthy or unhealthy EBRBs among children; and iv) the association between these typologies and the prevalence of overweight among children. These results may help identify risk profiles of parents who could be targeted for preventive interventions, and the results may help improve existing interventions designed to prevent childhood overweight and obesity.

Methods

Study design

This study was a cross-sectional, survey-based study.

Database

For our study, we had access to the Child Monitor, a database managed by the Municipal Health Services Department of the Gelderland-South region in the Netherlands. This database we also used in another published study. For that reason we will describe this method section in an uniform way to that study [33]. This database contains data collected in a cross-sectional survey conducted in 2009, to gain insight into the population’s health, lifestyle and well-being of children age 6 months to 12 years living in the Nijmegen region of the Netherlands [33, 34]. The Child Monitor is part of a monitoring cycle and is required by the Dutch Public Health Act. For the purpose of our study, we used data collected from parents with a child 4–12 years of age at the time of the survey, as the questions in the Child Monitor questionnaire about establishing EBRBs rules were only for parents of children 4–12 years of age. The Child Monitor questionnaire is part of the "Local and National Health Monitor", which uses standard questions. The questionnaire was available only in Dutch. Parents who have difficulty with the Dutch language were able to request help with completing the questionnaire.

Because these data were routinely collected and are anonymous, and because participation in the survey was voluntary, informed consent was not required for this study [33]. The research population that was asked to complete the Child Monitor questionnaire was well informed about the aim of the Child Monitor [33]. The design and method (data collection) of the Child Monitor complies with the legal provisions of the Personal Data Protection Act and the General Data Protection Regulation in the Netherlands and the protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the Municipal Health Services, Department of the Gelderland-South region in the Netherlands [33]. We received approval from the Director of the medical office of the Municipal Health Services Department of the Gelderland-South region in the Netherlands to use the Child Monitor database for our analyses and to report the results [33].

Participants

In 2009, a total of 15,991 parents/caregivers in the Gelderland-South region of the Netherlands with a child between the ages of 6 months and 12 years were randomly selected and invited to complete the Child Monitor questionnaire (either digitally or on paper). A total of 9,796 parents (61%) completed the questionnaire, and 4,865 of these questionnaires were about children 4–12 years of age at the time the questionnaire was completed.

Measures

Socio-demographic characteristics

The following demographic data were obtained from parents via the Child Monitor questionnaire: the child’s age, gender, and ethnicity, and the level of education of both parents (as an indicator of the SES). Ethnic background was determined by asking the country of birth of the child and for both parents. The parents were able to choose from the following six categories: “The Netherlands”, “Turkey”, “Morocco”, “Suriname”, “Netherlands Antilles” or “Other country”. The results were classified according to standard procedures established by Statistics Netherlands [35]: “Caucasian” (native-born and western migration background) and “non-Caucasian” (non-western migration background). The parent’s level of education was based on the highest level achieved and was classified as follows in accordance with international classification systems [36]: “low” (lower general secondary education, lower vocational training and primary school), “middle” (intermediate vocational training, higher general secondary training, or pre-university education), or “high” (higher vocational training or university education). If the educational level of both parents differed from each other, then the following criteria were used: If the parents’ level of education of one parent is low and the other is middle, then the education level of both parents is low; If parents’ level of education of one parent is low and the other is high, then the education level of both parents is middle; If the parents’ level of education of one parent is middle and the other is high, then the education level of both parents is middle.

Parental rules

Parental EBRB rules were assessed by asking the parents whether they had rules and/or agreements with their child regarding the following seven aspects: i) consuming snacks, ii) drinking SSBs, iii) eating fruit, iv) eating vegetables, v) eating breakfast each morning, vi) total hours per day spent watching television, DVDs, or other videos, and vii) total hours spent per day using the computer (including accessing the Internet and/or playing computer games). Parents were instructed to answer each question on a 3-point scale, with the following possible answers: “strict”, “indulgent”, or “no rules”. Parents were provided with brief definitions of these three categories: i) yes, and we stick to them; ii) yes, but we are flexible with them, and iii) no, we have no rules about it.

Energy balance-related behaviours

Parents were asked how often their child eats/consumes the following items: i) SSBs, ii) fruit, iii) vegetables, and iv) breakfast. Eight responses were possible, including “never”, “1 day a week” to “7 days a week”. In addition, parents were asked the following question: “On days that your child drinks a SSB, how many glasses does he/she drink?” Seven responses were possible, including “1 glass a day” to “6 glasses a day”, and “more than 6 glasses a day”.

To assess the child’s sedentary behaviour, parents were asked the following two questions: “How many days per week does your child watch television/videos/DVDs?” and “How many days per week does your child use the computer (including accessing the Internet and playing computer games)?” Eight answers were possible, including “never”, “1 day a week”, and “7 days a week”. In addition, parents were asked how much time their child spends on these activities on an average day, with the following possible answers: “less than half an hour a day”, “half an hour to 1 h per day”, “1- 2 h per day”, “2–3 h a day”, and “3 h a day or longer”.

The child’s body weight and height were determined by asking the following questions: “What is the current weight of your child in kg (without clothing)?” and “What is the current height of your child in cm (without shoes)?”.

Data analysis

First, we calculated each child’s body mass index (BMI) based on the child’s weight and height reported by the parents. Each child’s BMI was then converted to weight status, which was classified into three categories (“not overweight”, “overweight”, or “obese”) based on international cut-off values for childhood overweight as recommended by the International Obesity Task Force [37].

Next, means and frequencies were calculated for descriptive analyses of the demographic variables, parental EBRB rules, the child’s dietary and sedentary behaviors, and the child’s BMI. The child’s age was dichotomized into either 4–7 years and 8–12 years, as we expect that the application of rules likely differs between younger (4–7 years of age) and older (8–12 years of age) primary school students. For example, children 4–7 years of age are generally more dependent on their parents and are more easily influenced by parenting behaviors, whereas children 8–12 years of age are generally better able to reflect on their own and delve more deeply into the intent behind their parents’ rules. In addition, parents of younger primary school children who are overweight or obese tend to underestimate their child’s weight status [33, 38]. EBRBs were dichotomized in accordance with Dutch standards for healthy EBRBs in children [21,22,23]. For food behaviors, the responses were dichotomized into “not daily consumption” and “daily consumption of fruit, vegetables, and breakfast”; the responses based on SSBs were dichotomized into “drinks an average of less than two glasses a day” and “drinks an average of two or more glasses a day”. Sedentary behavior was dichotomized into “120 min or less screen time a day on average” and “more than 120 min of screen time a day on average”.

Next, we conducted latent class analysis (LCA) using the software package Mplus 5.1 in order to empirically identify heterogeneous classes of the degree of consistency in applying parental EBRB rules across dietary and sedentary behavioral domains. LCA was used with ordered and unordered categorical variables as indicators of the latent classes. We used the seven manifest variables of applying parental rules to identify distinct typologies (i.e., profiles or clusters).

To obtain the most appropriate and most parsimonious model, we examined each of the five latent profiles by conducting a series of five nested models. This analysis was performed separately for the two age groups (i.e., 4–7 years of age and 8–12 years of age). The bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT) [39] and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) [40] are reliable and consistent statistical indicators for determining the number of classes in a LCA model [41]. BIC is a commonly used and trusted indicator for comparing models, with a lower BIC value indicating a better-fitting model. BLRT uses bootstrap samples to estimate the distribution of the log-likelihood difference test statistic. Thus, instead of assuming that the differences have a known distribution (e.g., a chi-square distribution), BLRT estimates the distribution empirically [41]. The significance of the resulting BLRT ρ value is then used to assess whether there is a significant improvement in fit between models that differ in their number of included classes. In addition, we determined the Akaike information criteria (AIC) and entropy values. Final solutions were determined by performing a careful ad hoc examination of the model selection criteria and by including substantive considerations such as class interpretability and distinctiveness, representation of reality, and scientific relevance.

Last, in this study we wanted to examine how the typologies differed with respect to covariates such as socio-demographic characteristics, the child’s EBRBs, and the child’s weight status. Thus, the LCA models with covariates had fixed class-specific item probabilities, whereas the item probabilities values were fixed at values from the LCA model without covariates. This was done to ensure that the covariate values were estimated on the basis of the established final solution of classes. To test whether socio-demographic characteristics are differentially related to the subtypes of the degree of consistency in applying parental EBRB rules, we made comparisons regarding the characteristics’ links to each class, compared with all other classes as reference class. The child’s EBRBs were divided into four categories. The responses were categorized into “less than 3 days” “3 to 4 days”, “5 to 6 days” and “7 days a week consumption of fruit, vegetables, and breakfast”; the responses based on SSBs were categorized into “none”, “1 glass”, “2 glasses” and “3 or more glasses a day”. In these analyses posterior probabilities were used as weight factors in order to account for profile membership uncertainty. Missing data (less than 10% of data) were imputed by estimate regression in SPSS.

Results

Study population

The socio-demographic characteristics of the children and parents, the application of parental EBRB rules, the children’s EBRBs, and the children’s weight status are summarized in Table 1. The highest consistency among parents of children 4–12 years of age was in the application of strict rules regarding eating breakfast (approximately 88%), but more than 20% of these parents reported that they have no rules regarding their child drinking SSB, more than 30% have no rules regarding using the computer and even 40% of parents reported that they have no rules regarding their child’s television watching. Parents of children 8–12 years apply less strict rules regarding consuming snacks (42.3%, p p < 0.001), fruit (52%, p < 0.001), and watching television (21.8%, p = 0.041) compared to parents of children 4–7 years (47.1%, 61.5%, and 24.4% respectively). Less than 45% of children 4–12 years eat vegetables daily, and about 64% is drinking 2 or more SSB daily. Finally, children 8–12 years of age more often have two or more hours screen time a day, compared to children 4–7 years of age, 40.1% and 16.5% (p < 0.001) respectively.

Parental EBRB rules

To examine typologies regarding the degree of consistency with respect to applying parental EBRB rules across dietary and sedentary behavioral domains, on empirical grounds, the LCA models revealed that a five-class solution produced a better fit than a four-class solution, both for parents of children 4–7 years of age and for parents of children 8–12 years of age; specifically, this model yielded the lowest BIC and AIC values (see Table 2). However, due to the formation of two splinter groups in the five-class solution, this solution was highly similar to the four-class solution; therefore, we dropped one class on the grounds of parsimony, resulting in a four-class solution that was used in our subsequent analyses.

Typologies

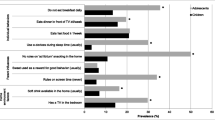

First, Fig. 1 shows the degree of consistency in applying parental EBRB rules in the four classes.

Second, Figs. 2 and 3 (representing parents of children 4–7 and 8–12 years of age, respectively) show four typologies (class profiles) regarding the degree of consistency with respect to applying parental EBRB rules across dietary and sedentary behavioral domains. Both Figs. 1 and 2 show that all four classes apply indulgent or strict rules regarding eating breakfast; breakfast was therefore not taken into account when naming and interpreting the classes.

Typologies of parents of children 4–7 years applying parental EBRB rules. The degree of consistency in applying parental EBRB rules is plotted on the y-axis; 0 = no rules, 0.5 = indulgent, and 1 = strict. -◆- Class1 “no rules diet, indulgent sedentary”, N = 584 (27.2%); -■- class 2 “indulgent diet, no rules sedentary”, N = 321 (15.9%); -▲- class 3 “overall indulgent”, N = 708 (34.2%); -x- class 4 “overall strict”, N = 465 (22.6%)

Typologies of parents of children 8–12 years applying parental EBRB rules. The degree of consistency in applying parental EBRB rules is plotted on the y-axis; 0 = no rules, 0.5 = indulgent, and 1 = strict. -◆- Class1 “no rules diet, indulgent sedentary”, N = 476 (17.1%); -■- class 2 “indulgent diet, no rules sedentary”, N = 882 (31.7%); -▲- class 3 “overall indulgent”, N = 1012 (36.3%); -x- class 4 “overall strict” N = 416 (14.9%)

An analysis of the four typologies in both groups of parents (i.e., parents of children 4–7 years of age and parents of children 8–12 years of age revealed the overall patterns of the four classes were similar between both groups of parents, which indicates that the four classes are relatively constant between the two age groups. The distribution of children over the classes differed between the groups.

Covariates

Socio-demographic covariates

Next, we tested whether the classes differed significantly with respect to the child’s age, the child’s gender, the child’s ethnicity, and/or the parents’ education level; these results are summarized in Table 3.

Among parents of children 4–7 years of age, class 2 (“indulgent diet, no rules sedentary”) contained more parents of younger children and more parents of boys compared to class 4 (“overall strict”). Among parents of children 8–12 years of age, class 4 (“overall strict”) contained more parents of younger children compared to both class 1 (“no rules diet, indulgent sedentary”) and class 3 (“overall indulgent”), and class 2 (“Indulgent diet, no rules sedentary”) contained more parents of boys compared to both class 3 and class 4.

Similar differences were found when we examined the data based on ethnicity, the parents’ education level, and the age groups of the children (i.e., parents of children 4–7 years of age and parents of children 8–12 years of age). Class 2 (“indulgent diet, no rules sedentary”) contained more non-Caucasian parents compared to the other classes, whereas we found no effect of ethnicity in class 1, class 3, or class 4. On average, the parents in class 2 (“indulgent diet, no rules sedentary”) had the lowest level of education, followed by class 1 (“no rules diet, indulgent sedentary”), class 3 (“overall indulgent”), and class 4 (“overall strict”). In addition, the parents in class 4 (“overall strict”) had a higher average level of education than the other three classes.

Energy balance-related behaviors

In both groups of parents (i.e., parents of children 4–7 years of age and parents of children 8–12 years of age) we found a significant association between the degree of consistency with respect of applying EBRB rules and EBRBs among children (see Table 4). The children of parents in class 4 (“overall strict”) ate significantly more fruits and vegetables, drank fewer SSBs, and had fewer sedentary behaviour activities compared to the children of parents in the other three classes. Moreover, the children of parents in class 2 (“indulgent diet, no rules sedentary”) ate significantly more fruit and vegetables compared to the children of parents in class 1 (“no rules diet, indulgent sedentary”).

In addition, among the parents of children 8–12 years of age, the children of parents in class 2 (“indulgent diet, no rules sedentary”) adhered more closely to the limit of < 2 h screen time per day compared to the children of parents in class 1 (“no rules diet, indulgent sedentary”). Moreover, the children of parents in class 1 (“no rules diet, indulgent sedentary”) ate significantly fewer fruits and vegetables compared to the children of parents in the other three classes.

Finally, we found no effect between classes and parental rules with respect to eating breakfast.

Overweight

As shown in Table 4, among the parents of children 4–7 years of age we found no association between the degree of consistency with respect to applying parental EBRB rules in children and the prevalence of overweight among children. However, among the parents of children 8–12 years of age, class 2 (“indulgent diet, no rules sedentary”) contained more parents of overweight children compared to class 1 (“no rules diet, indulgent sedentary”). We also found a slight difference between class 2 (“indulgent diet, no rules sedentary”) and class 4 (“overall strict”), with class 2 containing more parents of overweight children. Finally, we found no significant difference between class 1, class 3, and class 4 with respect to parents of overweight children.

Discussion

We identified four stable, distinct parental typologies with respect to applying dietary and sedentary behavior rules. In addition, we examined whether these typologies are associated with healthy and/or unhealthy EBRBs, and overweight among children in two non-overlapping age groups.

In addition, we found that children of parents who apply “overall strict EBRB rules” (class 4) practiced healthier behaviors (i.e., drank less SBBs, ate significantly more fruit and vegetables, and engaged in fewer sedentary activities) compared to children of parents in the other three classes. The parents in class 4 had the highest level of education. Moreover, among the children 8–12 years of age, the children whose parents apply “indulgent dietary behavior rules” (i.e., class 2 and class 3) ate more fruits and vegetables compared to children whose parents apply “no dietary behavior rules” (class 1). Therefore, we conclude that applying indulgent rules with respect to dietary behavior—although not ideal—is still better than having no rules at all.

Interestingly, children 8–12 years of age with parents in class 2 (“indulgent diet rules, no rules sedentary”) had the highest likelihood of being overweight compared to children of parents in class 1 (“no rules diet, indulgent rules sedentary’), while children 8–12 of parents in class 2 eat more fruit and vegetables, and were more likely to adhere to < 2 h of screen time per day compared to children 8–12 with parents in class 1 have. We might have expected that the children of parents in class 2 would engage in more sedentary behavior activities compared to children of parents in all of the three other classes, given that the parents in class 2 are the only parents who do not apply rules with respect to sedentary behavior activities. An explanation why children 8–12 years of parents in class 2 (“indulgent diet rules, no rules sedentary”) engaged in fewer sedentary activities compared to the children of parents in class 1 (“no dietary rules and indulgent sedentary rules”) might possibly because the parents with no sedentary rules (class 2) are either unaware or less aware of their child’s sedentary behavior activities and might therefore underestimate their child’s actual level of sedentary behavior activities. It is possibly that parents of these children also watch an excessive amount of television themselves and are therefore poor role models. This would make it difficult for such parents to apply sedentary behavior rules, particularly as the child becomes older; in addition, these parents may not be adequately aware of the importance of applying sedentary behavior rules. Class 2 contained more non-Caucasian (e.g. Turkish and Moroccan; non-western immigrants) parents and parents with the lowest level of education. This would be in line with the findings of Wijga et al., who previously reported that low maternal education, maternal overweight, and ethnicity are strongly associated with children who watch television frequently and are overweight [42]. In the Netherlands, children of parents with low SES and children of Turkish or Moroccan descent (non-Caucasian) are 2–4 times more likely to be overweight [43, 44]. It is therefore particularly important to educate these parents regarding the benefits of applying sedentary behavior rules, as these parents are an ideal target group for interventions designed to prevent and reduce overweight among children. Interventions at the policy level and group-oriented interventions are important for supporting parents. For example, ideally the same rules that parents set at home should also be applied at school, including providing healthier options. And it is important making the healthy options the easiest option to choose.

On the other hand, the degree of consistency with respect to applying EBRB rules is currently not associated with overweight in children 4–7 years of age. One possible explanation for these results is that changes in behaviors may need to occur for a longer period of time before BMI is affected. Another explanation is that the EBRB differs significantly between those two age groups. We found that compared to children 4–7 years of age, children 8–12 years of age eat less often daily fruit (65% vs. 51%), daily breakfast (98.3% vs. 97.1%) and have more than twice as often more than 2 h screentime a day (16.5% vs. 41.1%). For that reason, the difference in association with overweight seems most likely explained by the difference in EBRBs. Children 8–12 years of age have more unhealthy EBRBs compared to children 4–7 years of age.

We found that a lack of sedentary behavior rules in children 8–12 years of age—but not a lack of dietary behavior rules—is associated with overweight. This finding is consistent with the growing body of evidence suggesting that sedentary behavior (e.g., screen time) is independently and positively associated with poor health outcomes [45, 46] and is an important risk factor for childhood overweight [42, 47, 48]. Similarly, Wijga et al. also found that screen time—but none of the other behavioral factors like consumption of snacks or SSB examined was associated with childhood overweight [42]. Sedentary behavior has a twofold effect on energy balance. First, sedentary behavior is associated with eating more sugary, energy dense snacks and drinking more SSBs [49]; second, it reduces energy expenditure [50]. However, sedentary behavior should not necessarily be confused with a lower level of physical activity; indeed, the amount of screen time is correlated with obesity even among physically active children [51,52,53]. Thus, sedentary behavior rules should be applied to all children, and prevention programs must focus on educating parents with respect to the importance of establishing and consistently applying sedentary behavior rules for their children. This is consistent with the findings reported by de Jong et al. [54], who concluded that interventions should support parents in making home environmental changes, including applying sedentary behavior rules in order to reduce screen time.

Strengths and limitations

This study’s main strengths are the large dataset used and the robust, stable classes identified. On the other hand, some limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. First, the data were obtained from questionnaires that were completed by the parents. Thus, parents who report their child’s dietary and sedentary behaviors can potentially be biased due to social desirability and/or difficulty recalling the child’s actual behavior [55, 56]. In addition, the child’s height and weight were not obtained by professionals with calibrated measuring instruments. This would have been preferred, but was practically not feasible. Thus, the calculated BMI that was potentially based upon the parents’ misperception or inaccurate home measurement of their child’s weight and height, may have resulted in an overestimation or underestimation of their child’s weight status [57,58,59,60]. Second, the response rate was 61% of nearly 16,000 parents who were invited to participate. Given that lower SES families and ethnic minorities generally have a lower rate of participation in surveys [61, 62], this might have led to a selection bias. Third, our results are based on cross-sectional data, which precludes our ability to determine causality in our results. It is therefore difficult to determine which is the cause and which is the effect, as it is likely that rules influence the EBRBs and vice versa. Fourth, the data were collected in 2009; thus, the relevance of these outcomes may have changed since then. In the past 12 years, screen time has likely increased among children, particularly given the increased availability of smartphones, tablets, and gaming consoles. A 2021 survey among parents of children 7–12 years of age found that these children use a screen more than three hours each day. Moreover, nearly half (48%) of the parents indicated that their child has been using a screen significantly more since the COVID-19 lockdown than before the lockdown, and one-fourth of responding parents (26%) reported that they now find it more difficult to limit their child's screen time. And last, on average, only 28% of the parents reported that they impose restrictions. Nevertheless, the increased screen time by children, as well as the fact that parents find it difficult to limit this time, only increases the need to establish consistent rules regarding their child’s screen time [63]. Finally, the data contained no information regarding the parents’ physical activity behavior rules. Thus, additional research and longitudinal studies are needed in order to assess the causality between typologies of parental EBRB rules, EBRBs (including physical activity), and becoming overweight. In addition, qualitative studies are needed in order to determine why some parents apply indulgent or strict EBRB rules (or lack these rules).

Implications for practice and policy

The associations identified here provide additional evidence of the importance of the home environment, applying strict EBRB rules, and involving parents in programs designed to prevent childhood overweight. Our results may contribute to making healthcare professionals aware that children of parents who do not apply sedentary behavior rules are more likely to become overweight and underscore the need for parents to establish strict rules. Therefore, these insights may facilitate improving existing interventions designed to prevent overweight among children. In particular, parents with a low level of education and/or parents of non-Caucasian descent tend not to apply sedentary behavior rules. Therefore, effective parental education is warranted regarding the importance of applying EBRB rules—particularly sedentary behavior rules—and they must be supported with respect to applying these rules. Systematic screening of children’s health by professionals is therefore helpful, as it may provide regular opportunities to educate parents.

In addition to reducing the likelihood of childhood overweight, applying sedentary behavior rules has several other important benefits, including improving fitness, increasing self-esteem, promoting social behaviors, and improving academic performance [45].

Conclusion

Parents’ consistency in applying dietary and sedentary behavior rules is associated with healthy dietary and sedentary behaviors, and with overweight in children. These results underscore the need for parents to establish strict rules for their children, particularly regarding sedentary behavior in order to minimize the child’s likelihood of becoming overweight. These results can serve as a starting point for developing effective strategies to prevent overweight among children.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SSB:

-

Sugar-sweetened beverages

- EBRB:

-

Energy balance-related behavior

- SES:

-

Socio-economic status

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- LCA:

-

Latent class analysis

- BLRT:

-

Bootstrap likelihood ratio test

- BIC:

-

Bayesian information criteria

- AIC:

-

Akaike information criteria

- H0:

-

Null hypothesis

- Llh:

-

Likelihood

- SE:

-

Standard error

References

Wang Y, Lobstein T. Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2006;1(1):11–25.

Childhood overweight and obesity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood/en/.

Schonbeck Y, Talma H, van Dommelen P, Bakker B, Buitendijk SE, Hirasing RA, van Buuren S. Increase in prevalence of overweight in Dutch children and adolescents: a comparison of nationwide growth studies in 1980, 1997 and 2009. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27608.

Schönbeck Y, Buuren S, van,. Factsheet: Resultaten Vijfde Landelijke Groeistudie [Results of Fifth Dutch Growth Study]. In.: TNO. 2010.

Cislak A, Safron M, Pratt M, Gaspar T, Luszczynska A. Family-related predictors of body weight and weight-related behaviours among children and adolescents: a systematic umbrella review. Child care, health and development. 2012;38(3):321–31.

Zwiauer KF. Prevention and treatment of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents. Eur J Pediatr. 2000;159(1):S56–68.

Kremers SP, de Bruijn GJ, Visscher TL, van Mechelen W, de Vries NK, Brug J: Environmental influences on energy balance-related behaviors: a dual-process view. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3(9). https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1479-5868-3-9#citeas.

Van Koperen TM, Jebb SA, Summerbell CD, Visscher TL, Romon M, Borys JM, Seidell JC. Characterizing the EPODE logic model: unravelling the past and informing the future. Obes Rev. 2013;14(2):162–70.

Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2008;9(5):474–88.

Van der Star M. Kindermonitor 2010: Gezondheidsonderzoek kinderen 0–12 jaar regio Nijmegen [Child Monitor 2010: Health research in children 0–12 years of age in the Nijmegen region, the Netherlands]. GGD Nijmegen. 2010;1-67.

Brug J, van Stralen MM, te Velde SJ, Chinapaw MJ, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Lien N, Bere E, Maskini V, Singh AS, Maes L. Differences in weight status and energy-balance related behaviors among schoolchildren across Europe: the ENERGY-project. PloS one. 2012;7(4):e34742.

Te Velde SJ, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Thorsdottir I, Rasmussen M, Hagströmer M, Klepp K-I, Brug J. Patterns in sedentary and exercise behaviors and associations with overweight in 9–14-year-old boys and girls-a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):16.

Currie C. Social determinants of health and well-being among young people: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe Copenhagen. 2012.

Kremers SP. Theory and practice in the study of influences on energy balance-related behaviors. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79(3):291–8.

Swinburn B, Egger G, Raza F. Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Prev Med. 1999;29(6):563–70.

Lindsay AC, Sussner KM, Kim J, Gortmaker S. The role of parents in preventing childhood obesity. Future Child. 2006;16(1):169–86.

Golan M, Crow S. Parents are key players in the prevention and treatment of weight-related problems. Nutr Rev. 2004;62(1):39–50.

Pinard CA, Yaroch AL, Hart MH, Serrano EL, McFerren MM, Estabrooks PA. Measures of the home environment related to childhood obesity: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(1):97–109.

Faith MS, Van Horn L, Appel LJ, Burke LE, Carson JA, Franch HA, Jakicic JM, Kral TV, Odoms-Young A, Wansink B, et al. Evaluating parents and adult caregivers as “agents of change” for treating obese children: evidence for parent behavior change strategies and research gaps: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(9):1186–207.

Snoek HM, Larsen JK, Janssens JMAM, Engels RCME, Fransen GAJ, Molleman GRM, Wijk EEC, van: Parental involvement in intervention on chilhood obesity. In. Wageningen/Nijmegen, the Netherlands: GGD Regio Nijmegen (report CIAO phase 1); 2010.

Voedingscentrum: Gezond eten en bewegen met kinderen van 9–13 jaar [Healthy eating and physical activity with children 9–13 years of age]. In. the Netherlands. 2009.

Voedingscentrum. Richtlijnen Voedselkeuze [Guidelines for food choices]. In. Den Haag. 2011.

Kemper HGC, Ooijendijk WTM, Stiggelbout M. Consensus over de Nederlandse Norm voor Gezond Bewegen [Consensus on the Dutch Standard for Healthy Physical Activity]. Tijdschrift voor gezondheidswetenschappen. 2000;78(3):180–3.

Sleddens EF, Kremers SP, Stafleu A, Dagnelie PC, De Vries NK, Thijs C. Food parenting practices and child dietary behavior. Prospective relations and the moderating role of general parenting. Appetite. 2014;79:42–50.

Maccoby EE, Martin JA. Socialization in the context of the family: parent-child interaction. Handbook of child psychology. 1983;4:1–101.

Gerards SM, Sleddens EF, Dagnelie PC, de Vries NK, Kremers SP. Interventions addressing general parenting to prevent or treat childhood obesity. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6(2–2):e28-45.

Verloigne M, Van Lippevelde W, Maes L, Brug J, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Family- and school-based correlates of energy balance-related behaviours in 10–12-year-old children: a systematic review within the ENERGY (EuropeaN Energy balance Research to prevent excessive weight Gain among Youth) project. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(8):1380–95.

Johnson R, Welk G, Saint-Maurice PF, Ihmels M. Parenting styles and home obesogenic environments. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9(4):1411–26.

Rodenburg G, Oenema A, Kremers SP, van de Mheen D. Clustering of diet- and activity-related parenting practices: cross-sectional findings of the INPACT study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:36.

Veldhuis L, van Grieken A, Renders CM, Hirasing RA, Raat H. Parenting style, the home environment, and screen time of 5-year-old children; the “be active, eat right” study. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88486.

Gingold JA, Simon AE, Schoendorf KC. Excess screen time in US children: association with family rules and alternative activities. Clin Pediatr. 2014;53(1):41–50.

Leech RM, McNaughton SA, Timperio A. The clustering of diet, physical activity and sedentary behavior in children and adolescents: a review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:4.

Ruiter E, Saat J, Molleman G, Fransen G, van der Velden K, van Jaarsveld C, Engels R, Assendelft W. Parents’ underestimation of their child’s weight status. Moderating factors and change over time: A cross-sectional study. PloS one. 2020;15(1):e0227761.

Van der Star M: Regiorapport Kindermonitor 2009/2010: Gezondheid, welzijn en leefwijze van 0–12 jarigen in de regio Nijmegen. [Region report Child Monitor 2009/2010: Health, well-being and lifestyle of children 0 to 12 years of age in the Nijmegen region]. In. Nijmegen: GGD Gelderland-Zuid; 2010.

Keij I: Hoe doet het CBS dat nou? Standaarddefinitie allochtonen [How does Statistics Netherlands that? Standard Definition immigrants]. In: Index no 10. CBS [Statistics Netherlands]; 2000.

Eurostat: Task force on core social variables. Final report. In. Luxembourg: European Communities; 2007.

Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320(7244):1240–3.

Connell AM, Goodman SH. The association between psychopathology in fathers versus mothers and children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2002;128(5):746.

McLachlan G, Peel D. Mixtures of factor analyzers. Finite Mixture Models. 2000:238–256. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Finite+Mixture+Models-p-9780471006268

Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat. 1978;6(2):461–4.

Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equ Model. 2007;14(4):535–69.

Wijga AH, Scholtens S, Bemelmans WJ, Kerkhof M, Koppelman GH, Brunekreef B, Smit HA: Diet, screen time, physical activity, and childhood overweight in the general population and in high risk subgroups: prospective analyses in the PIAMA Birth Cohort. Journal of obesity 2010, 2010.

de Wilde JA, van Dommelen P, Middelkoop BJ, Verkerk PH. Trends in overweight and obesity prevalence in Dutch, Turkish, Moroccan and Surinamese South Asian children in the Netherlands. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(10):795–800.

Fredriks AM, Van Buuren S, Sing RA, Wit JM, Verloove-Vanhorick SP. Alarming prevalences of overweight and obesity for children of Turkish, Moroccan and Dutch origin in The Netherlands according to international standards. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94(4):496–8.

Tremblay MS, LeBlanc AG, Kho ME, Saunders TJ, Larouche R, Colley RC, Goldfield G, Gorber SC. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(1):1.

Tremblay MS, Colley RC, Saunders TJ, Healy GN, Owen N. Physiological and health implications of a sedentary lifestyle. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2010;35(6):725–40.

Adachi-Mejia A, Longacre M, Gibson J, Beach M, Titus-Ernstoff L, Dalton M. Children with a TV in their bedroom at higher risk for being overweight. Int J Obes. 2007;31(4):644–51.

Van Zutphen M, Bell AC, Kremer PJ, Swinburn BA. Association between the family environment and television viewing in Australian children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007;43(6):458–63.

Thomson M, Spence JC, Raine K, Laing L. The association of television viewing with snacking behavior and body weight of young adults. Am J Health Promot. 2008;22(5):329–35.

Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Nader PR, Broyles SL, Berry CC, Taras HL. Home environmental influences on children’s television watching from early to middle childhood. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23(3):127–32.

Melkevik O, Torsheim T, Iannotti RJ, Wold B. Is spending time in screen-based sedentary behaviors associated with less physical activity: a cross national investigation. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7(1):1.

Must A, Tybor D. Physical activity and sedentary behavior: a review of longitudinal studies of weight and adiposity in youth. Int J Obes. 2005;29:S84–96.

Hanley AJ, Harris SB, Gittelsohn J, Wolever TM, Saksvig B, Zinman B. Overweight among children and adolescents in a Native Canadian community: prevalence and associated factors. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(3):693–700.

de Jong E, Visscher TL, HiraSing RA, Heymans MW, Seidell JC, Renders CM. Association between TV viewing, computer use and overweight, determinants and competing activities of screen time in 4- to 13-year-old children. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(1):47–53.

Lovegrove AM. Social desirability and parental reporting of children’s health-related behaviours. 2011.

Koning M, De Jong A, de Jong E, Visscher TL, Seidell JC, Renders CM. Agreement between parent and child report of physical activity, sedentary and dietary behaviours in 9–12-year-old children and associations with children’s weight status. BMC psychology. 2018;6(1):14.

Scholtens S, Brunekreef B, Visscher TL, Smit HA, Kerkhof M, De Jongste JC, Gerritsen J, Wijga AH. Reported versus measured body weight and height of 4-year-old children and the prevalence of overweight. The European Journal of Public Health. 2007;17(4):369–74.

Davis H, Gergen PJ. Mexican-American mother’s reports of the weights and heights of children 6 months through 11 years old. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94(5):512–6.

Akerman A, Williams ME, Meunier J. Perception versus Reality An Exploration of Children’s Measured Body Mass in Relation to Caregivers’ Estimates. J Health Psychol. 2007;12(6):871–82.

Brettschneider A-K, Ellert U, Schaffrath Rosario A. Comparison of BMI derived from parent-reported height and weight with measured values: results from the German KiGGS study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9(2):632–47.

Hoopman R, Terwee CB, Devillé W, Knol DL, Aaronson NK. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the SF-36 health survey for use among Turkish and Moroccan ethnic minority populations in the Netherlands. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(6):753–64.

Méndez M, Font J. Surveying ethnic minorities and immigrant populations: Methodological challenges and research strategies. the Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press; 2013.

Monitor mediagebruik 7–12 jaar. Een onderzoek naar omgang met en gebruik van media(devices) van kinderen tussen 7 en 12 jaar, en de rol die ouders hierin spelen. [Monitor media use 7–12 years. An investigation into dealing with and use of media (devices) of children between 7 and 12 years, and the role that parents play in this.]. In.: Netwerk Mediawijsheid; 2021.

Health monitor [Gezondheidsmonitors] https://ggdghor.nl/thema/gezondheidsmonitor/

Acknowledgements

We thank the Municipal Health Services of the Gelderland-South for giving us access to their large database, the Child Monitor. We are particularly grateful to Marlene van de Star for collecting data from the Child Monitor and preparing the dataset. This research project is part of the second phase of the Consortium Integrated Approach Overweight (CIAO), which is a partnership between five major local collaborations among academic institutions, municipal health services, local authorities and other relevant sectors in Nijmegen, Maastricht, Rotterdam, Amsterdam, and Leiden. The aim of CIAO is to provide communities with elements of a coherent integrated multisector approach to overweight prevention that are based on the principles of the French EPODE program (Ensemble Prevenons l’Obesité Des Enfants).

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw; project number 505010296015, 200100001); this funding source played no role in the design or execution of this study and did not play any role in the analysis or interpretation of the data, nor in the decision to publish the results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the design of this study. ER and MK performed the statistical analysis and data interpretation. ER wrote draft versions of the manuscript. GF and GM contributed to the interpretation of the data and writing of the manuscript. All other authors are supervisors and were involved in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approve the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Child Monitor questionnaire is part of the "Local and National Health Monitor". The Local and National Health Monitor is a partnership between national and regional public health organizations on behalf of the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. The organizations have made agreements with each other on how to use the collected data to perform local and national surveillance tasks [64]. The design and method (data collection) of the Child Monitor complies with the legal provisions of the Personal Data Protection Act and the General Data Protection Regulation in the Netherlands and the protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the Municipal Health Services, Department of the Gelderland-South region in the Netherlands. It also complies with the protocols of the Municipal Health Service that are part of the Dutch Harmonization of Quality Assessment in the Healthcare Sector (HKZ) system that is periodically tested externally. We received approval from the Director of the medical office of the Municipal Health Services Department of the Gelderland-South region in the Netherlands to use the Child Monitor database for our analyses and to report the results. This director is formally responsible for conducting of the Child Monitor. Consent to participate was not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruiter, E.L.M., Fransen, G.A.J., Kleinjan, M. et al. The degree of consistency of applying parental dietary and sedentary behavior rules as indicators for overweight in children: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 22, 348 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12742-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12742-8