Abstract

Background

Over the past decade, rates of drug poisoning deaths have increased dramatically in Canada. Current evidence suggests that the non-medical use of synthetic opioids, stimulants and patterns of polysubstance use are major factors contributing to this increase.

Methods

Counts of substance poisoning deaths involving alcohol, opioids, other central nervous system (CNS) depressants, cocaine, and CNS stimulants excluding cocaine, were acquired from the Canadian Vital Statistics Death Database (CVSD) for the years 2014 to 2017. We used joinpoint regression analysis and the Cochrane-Armitage trend test for proportions to examine changes over time in crude mortality rates and proportions of poisoning deaths involving more than one substance.

Results

Between 2014 and 2017, the rate of substance poisoning deaths in Canada almost doubled from 6.4 to 11.5 deaths per 100,000 population (Average Annual Percent Change, AAPC: 23%, p < 0.05). Our analysis shows this was due to increased unintentional poisoning deaths (AAPC: 26.6%, p < 0.05) and polysubstance deaths (AAPC: 23.0%, p < 0.05). The proportion of unintentional poisoning deaths involving polysubstance use increased significantly from 38% to 58% among males (p < 0.0001) and 40% to 55% among females (p < 0.0001). Polysubstance use poisonings involving opioids and CNS stimulants (excluding cocaine) increased substantially during the study period (males AAPC: 133.1%, p < 0.01; females AAPC: 118.1%, p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Increases in substance-related poisoning deaths between 2014 and 2017 were associated with polysubstance use. Increased co-use of stimulants with opioids is a key factor contributing to the epidemic of opioid deaths in Canada.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It is estimated that over 27,000 deaths were either directly or indirectly attributable to substance use in Canada in 2017 (excluding tobacco) [1]. This included over 11,000 substance poisoning deaths, 99% of which were attributable to alcohol, opioids, other central nervous system (CNS) depressants (such as benzodiazepines and barbiturates), cocaine, and other CNS stimulants (such as amphetamines). Over the past decade, rates of substance poisoning deaths have increased dramatically in Canada [2, 3]. This increase has largely been associated with the non-medical use of prescription opioids or other illegal opioids [2, 4,5,6]. However, since 2015, evidence suggests increases in stimulant use across Canada began contributing to rising numbers of substance-related poisoning deaths [5, 7,8,9]. This evidence suggests co-use of opioids and stimulants as well as other patterns of polysubstance use may be contributing to the increase in substance poisoning deaths [9,10,11,12].

Polysubstance use, i.e., the concurrent or simultaneous use of more than one substance, is common in Canada [13,14,15,16,17]. Compared to individuals using primarily one substance, polysubstance use is more reliably associated with mental illness [18, 19], negative social and financial impacts [20], and poor treatment outcomes [21, 22]. Polysubstance use is also associated with elevated risk of fatal and non-fatal substance-related poisonings [18, 23, 24]. Despite the frequency of polysubstance use and its strong association with substance-related morbidity and mortality, there are currently no national-level statistics on the impacts of polysubstance use in Canada. To fill this gap, this study presents counts, rates and proportions of polysubstance-related poisoning deaths involving alcohol, opioids, other CNS depressants, cocaine, and other CNS stimulants excluding cocaine using data acquired from the Canadian Vital Statistics Death Database for the years 2014 to 2017.

Methods

Data sources and cause of death variables

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. This study examined death record data from the Statistics Canada holdings of the Multiple Cause of Death files (MCOD). The MCOD database provides information on a single underlying cause of death (UCD), up to 20 additional causes and demographic data from all provincial and territorial vital statistics registries on all deaths occurring in Canada. An underlying cause of death is defined as the “disease or injury which initiated the train of events leading directly to death, or the circumstances of the accident or violence which produced the fatal injury” [25]. The UCD and contributing causes of death are listed by the medical examiner/coroner and classified according to the World Health Organization “International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10thRevision” [25]. The MCOD files include not only the underlying cause of death, but also the immediate cause of death and other intermediate and contributory conditions listed on the death certificate. Population data used for generating crude rates were obtained from Statistics Canada [26].

Case selection and inclusion criteria

The dataset includes all death records from January 1st, 2014 to December 31st, 2017 where a substance poisoning is listed as the UCD. A substance poisoning death is an acute toxicity death resulting from the direct effects of consuming an exogenous substance and can be intentional or unintentional[25]. ICD-10 codes for the following substance categories were included: alcohol, opioids, other central nervous system (CNS) depressants, cocaine, and CNS stimulants excluding cocaine. Poisoning deaths resulting from other substance use categories were not included in this categorical analysis; previous work has shown that virtually all substance use poisoning deaths occur within the five chosen substance use categories[27]. The analysis includes the ICD-10 codes X41-X45 (unintentional poisoning) and X61-65 (intentional poisoning). The codes for undetermined intent (Y11-Y15), were also included and considered as unintentional poisonings in this study. The multiple cause of death data using the ICD-10 “T” codes is used to identify poisoning deaths resulting from combinations of substances across the selected substance categories. Among deaths with substance poisoning as the underlying cause, the type of substance or substance category is indicated by the following ICD-10 multiple cause-of-death codes: alcohol (T51.91, T51.92, T51.94), opioids (T40.0, T40.1, T40.2, T40.3, T40.4, or T40.6); other CNS depressants (T42.3, T42.2, T42.6, T42.7), cocaine (T40.5); and CNS stimulants excluding cocaine (T43.6). Substance-related poisoning deaths were categorized as single substance when only one of the five substance categories was listed as a cause of death, and polysubstance when two or more of the five substance categories were listed. Counts across all unique combinations of substances were obtained and stratified by year, sex, and intention. Records in which a decedent had multiple substances listed upon death is only represented once for that combination.

To meet data confidentially requirements, Statistics Canada uses a disclosure method called the Laplace mechanism leading to some loss in precision of the dataset. Briefly, the Laplace mechanism adds a measure of noise to each row-level observation so as to satisfy privacy concerns in releasing Vital Statistics data. This mechanism is applied internally by the Statistics Canada Vital Statistics Team before the data is released to researchers as standard practice. The variances of the estimates were made to equal a value of two. Application of the disclosure method can also result in negative estimations when counts are very low. Following the methodology recommended by Statistics Canada, all negative counts were truncated to zero [28]. This resulted in a small positive bias in some combination counts.

Statistical analyses

Crude mortality rates were calculated by sex and intent for the years 2014 to 2017 and were expressed as the number of deaths reported each calendar year divided by the estimates of the July 1st resident population of Canada (per 100,000 persons and 95% confidence interval [CI]).

Counts and crude mortality rates for the year 2017 exclude substance poisoning deaths in the Yukon territory as this data was not available from Statistics Canada’s Vital Statistics Database at the time of data extraction (September 2019). Analyses were carried out on all unintentional and intentional poisoning deaths and stratified by type of poisoning death (single substance versus polysubstance and across combinations of substance groups). For each year*sex stratum, proportions of all poisoning deaths involving more than one substance group (“polysubstance”) were calculated overall and for each substance group. Crude mortality rates were analyzed with Joinpoint Regression version 4.8.0.1 (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD) [29] to determine whether changes between 2014 and 2017 were significant [30]. Temporal trends in proportions were assessed using the Cochran-Armitage test for linear trends, using the ExcelStat data analysis add-on for Excel. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

Trends in mortality rates of substance poisoning deaths

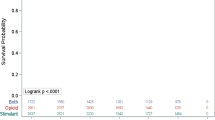

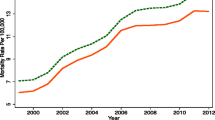

Figure 1 presents the crude mortality rates of all substance poisoning deaths in Canada between 2014 and 2017. According to the data, mortality rates increased 1.8-fold among females (4.22 to 5.96 deaths/100,000) and 2.0-fold among males (8.69 to 17.19 deaths/100,000) (Table 1). In 2017, the mortality rate for substance poisoning deaths was almost three-times higher among males compared to females (Table 1). Mortality rates for polysubstance versus single substance deaths are plotted in Fig. 2 and estimates from the joinpoint analyses are presented in Table 2. The data show that mortality rates for polysubstance deaths increase significantly overall (2.6-fold, AAPC=40.5%), and among both males (3.0-fold, AAPC=45.9%) and females (2.0-fold, AAPC=27.6%). Mortality rates for deaths involving only one substance, defined as single substance deaths, remained unchanged across all groups between 2014 and 2017. Mortality rates for intentional versus unintentional deaths are plotted in Fig. 3 and estimates from the joinpoint analyses are presented in Table 3. The data show that mortality rates for unintentional deaths increase significantly overall (1.9-fold, AAPC=26.6%) and among males (2.1-fold, 29.9%). There were no significant change in rates of unintentional deaths among females. Mortality rates for intentional deaths remain unchanged across all groups (Table 3).

Contribution of substance categories to polysubstance deaths

The percentage of unintentional substance poisoning deaths identified as polysubstance use deaths increased significantly during the study period, from 39% (756 of 1949 deaths) in 2014 to 57% (2228 of 3882 deaths) in 2017 (Table 4). To examine how each substance category (alcohol, depressants, opioids, cocaine, and other stimulants) contributed individually to total counts of unintentional polysubstance poisoning deaths, we calculated the proportion of all poisoning deaths for each substance where more than one substance contributed to death (i.e., “polysubstance” proportions for each substance category, Table 4). For example, among all deaths where alcohol was listed as a cause of death, this is the proportion of those records which also had another substance category present. Almost all substance categories among both males and females were increasingly likely over the study period to be involved in polysubstance deaths, as compared to single substance deaths. Indeed, in 2017 over 50% of deaths in each substance category had another substance category present. Other CNS depressants had the highest proportion of deaths that involved another substance category (95% of deaths involving other CNS depressants in 2017 included another substance category). Cocaine and other CNS stimulants also had high proportions (85% and 88% in 2017, respectively).

Most common polysubstance combinations

We next determined the five most frequent polysubstance poisonings that caused unintentional deaths between 2014 and 2017 towards understanding which substance combinations were the most likely to be involved in unintentional poisoning deaths. Mortality rates for the most frequent polysubstance combinations among males are plotted in Fig. 4, and the most frequent polysubstance combinations among females are plotted in Fig. 5. Counts, rates, and estimates from the joinpoint analyses are presented in Table 5. The data show that the largest increases in polysubstance mortality rates among males occurred from combinations of opioids and other CNS stimulants (excluding cocaine) (12.9-fold increase, AAPC=133.1%), opioids, cocaine, and other CNS stimulants (2.8-fold increase, AAPC=79.9%) and opioids and cocaine (3.3-fold increase, AAPC=55.5%). Among females, the largest increases in polysubstance mortality rates occurred from combinations of opioids and other CNS stimulants (excluding cocaine) (13.3-fold increase, AAPC=118.1%), opioids, cocaine, and other CNS stimulants (2.6-fold increase, AAPC=38.4%), and opioids and cocaine (2.3-fold increase, 37.4%). In 2017, opioids and cocaine, and opioids and CNS stimulants (excluding cocaine) were the most common polysubstance unintentional poisoning deaths among both males and females. All the top polysubstance combinations among both males and females included opioids, and mortality rates for almost all of these polysubstance combinations increased significantly between 2014 and 2017. Combinations of opioids and alcohol did not increase significantly for either males or females in this period. The same was true for combinations of opioids and other CNS depressants for females.

Interpretation

We examined the contribution of polysubstance use to substance poisoning deaths in Canada between 2014 and 2017. We show that increasing rates of unintentional poisoning deaths in Canada during this time were largely attributable to increasing rates of polysubstance poisoning deaths. Polysubstance poisoning mortality rates increased far more than single-substance death rates, and by 2017, more than half of all unintentional poisoning deaths were polysubstance deaths. These increases were much more dramatic among males. All substance categories examined during the study period were increasingly involved in polysubstance deaths, as compared to single substance deaths. Combinations of opioids with cocaine and/or CNS stimulants excluding cocaine were associated with the largest increases in unintentional polysubstance poisoning deaths during the study and accounted for the most unintentional deaths from polysubstance use in 2017.

Canadian data indicate that unintentional poisoning deaths have increased almost 3-fold between 2008 and 2018 in Canada [3]. Rates of unintentional poisoning deaths in Canada have further accelerated since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic [4, 9, 31]. This increase has been largely driven by the use (either deliberate or accidental) of synthetic opioids like fentanyl [2, 4, 6, 9]. According to toxicology data in both Canadian and American jurisdictions, trends in overdose deaths involving cocaine and other stimulants have also increased substantially in the past five to ten years [4,5,6, 32, 33]. Synthetic opioids, mostly illegally sourced fentanyl, also underlie these recent increases in stimulant-related poisoning deaths [2, 5, 9, 10, 34,35,36]. This is likely driven in part by consuming drugs from the illegal supply that contain both synthetic opioids and stimulants (whether intentionally or not). Toxicological analysis of illegal drugs seized by Canadian law enforcement agencies suggests that, when stimulants do co-occur with opioids in the same drug sample, the opioid is usually fentanyl or one of its analogues [8]. Data from the United States further demonstrate that opioid-related overdoses in recent years are generally more likely to involve at least one other substance category [36,37,38,39,40,41]. Hence, polysubstance use, and more specially the co-use of opioids and stimulants, is becoming a primary driver of increased substance poisoning deaths in Canada.

Results suggest the use of opioids in combination with other substances, particularly stimulants, needs to be addressed in efforts to curb the epidemic of opioid deaths in Canada across the spectrum of prevention, harm reduction, and treatment. Specifically, measures that address the unpredictability of the illegal drug supply would reduce harms related to polysubstance use (whether multiple substances are used deliberately or not) [8]. These may include expanding access to reliable information about drug contents through drug checking services, as well as access to overdose prevention services such as supervised consumption/ overdose prevention sites and take home naloxone kits [42]. Drug contamination and other upstream risk factors may be addressed by interventions that provide a legal, pharmaceutical-grade supply of opioids and non-opioid substances [43,44,45]. In all cases, people who use drugs must be involved throughout implementation and evaluation to ensure services are relevant to the preferences and needs of people who use drugs in different contexts [45,46,47].

In general, prevention efforts can target common pathways that lead to substance use disorders, treatment strategies can focus on common features across substances, and service delivery can also be structured in a way to address issues associated with multiple types of substance use [23, 37, 41]. Polysubstance use also has important implications for public health surveillance and research. Identifying factors (e.g., demographics, behaviors) linked to polysubstance use can inform interventions and prevention pathways, while patterns of polysubstance use should be monitored alongside trends of other substances in a timely fashion, particularly as the COVID-19 pandemic has rapidly impacted the illegal drug supply and substance use behaviors.

Limitations

We limited our analysis to death records for poisoning deaths involving only five different substance categories that frequently cause substance poisoning deaths [3, 46,47,48]. Cannabis, hallucinogens, solvents and inhalants, antidepressants and other psychoactive substances were excluded from the analysis. Methodologically, this exclusion was necessary to avoid very low counts (close to zero or negative estimations) for polysubstance combinations that appeared infrequently in the vital statistics database. Although there is evidence suggesting that these other substance classes more rarely cause fatal poisonings on their own [5, 49,50,51], they could be involved in poisoning deaths primarily caused by other substances [5, 52,53,54] and warrant further investigation to better characterize the polysubstance nature of poisoning deaths. In addition, our definition of polysubstance is conservative and confined by broad substance categories; the dataset analysed for this study does not differentiate between different types of substances within each category. For instance, a poisoning death caused by both heroin and fentanyl for example, would be considered a single substance poisoning death.

Our study methodology also does not distinguish between deliberate polysubstance use (when an individual explicitly uses two or more substances), and accidental polysubstance use (when an individual thinks they are using only one substance, but it is contaminated or adulterated by another substance category). Both deliberate and accidental polysubstance use may underlie increases in unintentional poisoning deaths from the co-use of opioids and stimulants. For instance, fentanyl and related synthetic opioids are often consumed unknowingly with other substances [8, 34, 55,56,57,58] while the popularity and desire for using both opioids and stimulants has also grown among people who use either substance [56, 59]. These different pathways leading to polysubstance use is an area for further investigation.

Another important limitation of this dataset is that counts of poisoning deaths are not segregated by age, as this would result in small estimates that would need to be supressed to prevent identification of individual records. Therefore, we were unable to investigate any age-specific trends or calculate any age-adjusted death rates. An analysis of demographic characteristics from a comparable dataset from overall intentional and unintentional injuries for 2017, which are largely (but not exclusively) accounted for by substance use poisonings, shows the majority of intentional and unintentional injury deaths occurred in the 35-64 age group (See Supplementary Table 1). Finally, our study ultimately depends on the accuracy of toxicology screenings carried out by coroners and medical examiners, and proper identification and coding of substances as contributing causes of death. Not only can these processes be imperfect, but there can be inconsistent practices in toxicology screening and testing leading to inaccuracies in death records for substance poisoning deaths [2, 60, 61]. More specifically, because collecting evidence to ascertain intent is especially difficult, intentional deaths (suicides) may frequently be misclassified as unintentional deaths or deaths with undetermined intent [61]. This would lead to an overestimation of the number and rates of unintentional poisoning deaths in our study. The time required to complete death investigations and classify the cause of death may have also resulted in an underestimation of poisoning deaths in our study, particularly for more recent years.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining national patterns of polysubstance poisoning deaths in the era of the opioid epidemic. A multitude of intersecting factors are causing increased rates of substance poisoning deaths in Canada, including increased use of stimulants from the illegal drug supply, contamination of the illegal drug supply with fentanyl/synthetic opioids, and a changing landscape of polysubstance use where co-consumption of opioids, stimulants and other substances is increasingly more popular. Improved surveillance of polysubstance use patterns and harms will be essential to informing responses to the ongoing opioid crisis in Canada. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to fuel substance poisoning deaths, these data highlight the need for essential services and supports to be accessible for people most at risk and the need to expand prevention, treatment, and harm reduction activities.

Availability of data and materials

The results/data/figures in this manuscript have not been published elsewhere, nor are they under consideration by another publisher.

The authors are not able to share the raw data. The dataset used to conduct this analysis was acquired through Statistics Canada and is not owned by the authors. Due to the data sharing agreement the authors established with Statistics Canada, we are unable to share the raw data publicly, however the data used for this study can be acquired directly from Statistics Canada.

Abbreviations

- AAPC:

-

Average Annual Percent Change

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- CNS:

-

Central Nervous System

- CVSD:

-

Canadian Vital Statistics Death Database

- MCOD:

-

Multiple Cause of Death

- UCD:

-

Underlying Cause of Death

References

Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms Scientific Working Group. Canadian substance use costs and harms visualization tool, version 2.0.0 [Online tool]. Available: https://csuch.ca/explore-the-data/. Accessed 4 May 2021.

Belzak L, Halverson J. Evidence synthesis-the opioid crisis in Canada: a national perspective. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2018;38(6):224–33.

Jiang A, Belton KL, Fuselli P. Evidence summary on the prevention of poisoning in Canada. Toronto: Parachute; 2020. Available: https://parachute.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Evidence-Summary-on-Poisoning-in-Canada-UA.pdf. Accessed 4 May 2021.

Illicit drug toxicity deaths in BC, January 1, 2011 – February 28, 2021. 2021. Victoria: British Columbia Coroners Service; 2021. Available: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/statistical/illicit-drug.pdf. Accessed 4 May 2021.

Crabtree A, Lostchuck E, Chong M, et al. Toxicology and prescribed medication histories among people experiencing fatal illicit drug overdose in British Columbia, Canada. CMAJ. 2020;192(34):E967–72.

Opioid mortality surveillance report - analysis of opioid-related deaths in Ontario July 2017–June 2018. Ottawa: Public Health Ontario; 2019. Available: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/O/2019/opioid-mortality-surveillance-report.pdf. Accessed 4 May 2021.

Canadian Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (CCENDU) Working Group. Changes in stimulant use and related harms: focus on methamphetamine and cocaine. Ottawa: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction; 2019. Available: https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-05/CCSA-CCENDU-Stimulant-Use-Related-Harms-Bulletin-2019-en.pdf. Accessed 4 May 2021.

Payer DE, Young MM, Maloney-Hall B, et al. Adulterants, contaminants and co-occurring substances in drugs on the illegal market in Canada: an analysis of data from drug seizures, drug checking and urine toxicology. Ottawa. Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. 2020; Available: http://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2020-04/CCSA-CCENDU-Adulterants-Contaminants-Co-occurring-Substances-in-Drugs-Canada-Report-2020-en.pdf. Accessed 4 May 2021.

Opioid- and stimulant-related harms in Canada. Public Health Agency of Canada. Ottawa; 2021. Available: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids-stimulants/. Accessed 4 May 2021.

Al-Tayyib A, Koester S, Langegger S, et al. Heroin and methamphetamine injection: an emerging drug use pattern. Subst Use Misuse. 2017;52(8):1051–8.

Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Kasper ZA. Polysubstance use: a broader understanding of substance use during the opioid crisis. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(2):244–50.

Ellis MS, Kasper ZA, Cicero TJ. Twin epidemics: the surging rise of methamphetamine use in chronic opioid users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;193:14–20.

Barrett SP, Gross SR, Garand I, et al. Patterns of simultaneous polysubstance use in Canadian rave attendees. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40(9-10):1525–37.

Konefal S, Maloney-Hall B, Urbanoski K. National Treatment Indicators Working Group. National Treatment Indicators Report: 2016–2018 Data. Ottawa: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction; 2021. Available: https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2021-01/CCSA-National-Treatment-Indicators-2016-2018-Data-Report-2021-en.pdf. Accessed 4 May 2021.

Roy É, Richer I, Arruda N, et al. Patterns of cocaine and opioid co-use and polyroutes of administration among street-based cocaine users in Montréal, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2013;24(2):142–9.

Ross LE, Bauer GR, MacLeod MA, et al. Mental health and substance use among bisexual youth and non-youth in Ontario, Canada. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e101604.

Zuckermann AM, Williams GC, Battista K, et al. Prevalence and correlates of youth poly-substance use in the COMPASS study. Addict Behav. 2020;107:106400.

Connor JP, Gullo MJ, White A, et al. Polysubstance use: diagnostic challenges, patterns of use and health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27(4):269–75.

Hassan AN, Le Foll B. Polydrug use disorders in individuals with opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;198:28–33.

Brache K, Stockwell T, Macdonald S. Functions and harms associated with simultaneous polysubstance use involving alcohol and cocaine. J Subst Use. 2012;17(5–6):399–416.

Bailey AJ, Farmer EJ, Finn PR. Patterns of polysubstance use and simultaneous co-use in high risk young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;205:107656.

McCabe SE, West BT, Jutkiewicz EM, et al. Multiple DSM-5 substance use disorders: A national study of US adults. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2017;32(5):e2625.

Compton WM, Valentino RJ, DuPont RL. Polysubstance use in the US opioid crisis. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;1:41–50.

Bohnert AS, Walton MA, Cunningham RM, et al. Overdose and adverse drug event experiences among adult patients in the emergency department. Addict Behav. 2018;86:66–72.

International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th Revision. World Health Organization. Geneva: Wordl Health Organization; 2011. Available https://www.who.int/classifications/icd/ICD10Volume2_en_2010.pdf. Accessed 4 May 2021.

Population estimates on July 1st, by age and sex [Table 17-10-0005-01]. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2020. Available: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000501. Accessed 25 June 2020.

Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms Scientific Working Group. Canadian substance use costs and harms (2007–2014). Ottawa: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction; 2018. Available: https://csuch.ca/publications/CSUCH-Canadian-Substance-Use-Costs-Harms-Report-2018-en.pdf. Accessed 22 Nov 2021.

Holohan N, Antonatos S, Braghin S, et al. The bounded Laplace mechanism in differential privacy. arXiv preprint arXiv. 2018;1808:10410.

Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 4.8.0.1 - April 2020; Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute.

Kim H-J, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, et al. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rate. Stat Med. 2000;19:335–51.

Preliminary Patterns in Circumstances Surrounding Opioid-Related Deaths in Ontario during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Toronto: Ontario Drug Policy Research Network, Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario/Ontario Forensic Pathology Service, Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion, Centre on Drug Policy Evaluation; 2020. Available: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/o/2020/opioid-mortality-covid-surveillance-report.pdf?la=en. Accessed 4 May 2021.

Hedegaard H, Bastian BA, Trinidad JP, et al. Drugs most frequently involved in drug overdose deaths: United States, 2011-2016. Mon Vital Stat Rep. 2018:67(9).

Kariisa M, Scholl L, Wilson N, et al. Drug overdose deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants with abuse potential—United States, 2003–2017. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2019;68(17):388–95.

Bach H, Jenkins V, Aledhaim A, et al. Prevalence of fentanyl exposure and knowledge regarding the risk of its use among emergency department patients with active opioid use history at an urban medical center in Baltimore, Maryland. Clin Toxicol. 2020;58(6):460–5.

Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Compton WM. Recent increases in cocaine-related overdose deaths and the role of opioids. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(3):430–2.

Rhee TG, Ross JS, Rosenheck RA, et al. Accidental drug overdose deaths in Connecticut, 2012–2018: The rise of polysubstance detection? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;205:107671.

Barocas JA, Wang J, Marshall BD, et al. Sociodemographic factors and social determinants associated with toxicology confirmed polysubstance opioid-related deaths. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;200:59–63.

Cano M, Oh S, Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG. Cocaine use and overdose mortality in the United States: Evidence from two national data sources, 2002–2018. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;214:108148.

Gladden RM, O’Donnell J, Mattson CL, Seth P. Changes in opioid-involved overdose deaths by opioid type and presence of benzodiazepines, cocaine, and methamphetamine—25 states, July–December 2017 to January–June 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2019;68(34):737.

Golladay M, Donner K, Nechuta S. Using statewide death certificate data to understand trends and characteristics of polydrug overdose deaths in Tennessee, 2013–2017. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;41:43–8.

King NB, Fraser V, Boikos C, et al. Determinants of increased opioid-related mortality in the United States and Canada, 1990–2013: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(8):e32–42.

Wallace B, Pagan F, Pauly BB. The implementation of overdose prevention sites as a novel and nimble response during an illegal drug overdose public health emergency. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;66:64–72.

Harris MT, Seliga RK, Fairbairn N, Nolan S, Walley AY, Weinstein ZM, et al. Outcomes of Ottawa, Canada's Managed Opioid Program (MOP) where supervised injectable hydromorphone was paired with assisted housing. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;29(98):103400.

Fleming T, Barker A, Ivsins A, Vakharia S, McNeil R. Stimulant safe supply: a potential opportunity to respond to the overdose epidemic. Harm Reduct J. 2020;17(1):6.

Canadian Association of People Who Use Drugs. Safe supply concept document. Vancouver: Author; 2019. Retrieved from https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/capud-safe-supply-conceptdocument.pdf.

Bourque S, Pijl EM, Mason E, Manning J, Motz T. Supervised inhalation is an important part of supervised consumption services. Can J Public Health. 2019;110(2):210–5.

Wallace B, van Roode T, Pagan F, Phillips P, Wagner H, Hore D. What is needed for implementing drug checking services in the context of the overdose crisis? A qualitative study to explore perspectives of potential service users. Harm Reduct J. 2020:17(29).

Kanny D, Brewer RD, Mesnick JB, et al. Vital signs: alcohol poisoning deaths—United States, 2010–2012. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2015;63(53):1238.

Ruhm CJ. Drug involvement in fatal overdoses. SSM Popul Health. 2017;3:219–26.

Warner M, Trinidad JP, Bastian BA, et al. Drugs most frequently involved in drug overdose deaths: United States, 2010–2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016:65(10).

Darke S, Duflou J, Peacock A, et al. Characteristics and circumstances of death related to new psychoactive stimulants and hallucinogens in Australia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107556.

Maslej MM, Bolker BM, Russell MJ, et al. The mortality and myocardial effects of antidepressants are moderated by preexisting cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Psychother Psychosom. 2017;86(5):268–82.

Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Brooks DE, et al. 2014 annual report of the american association of poison control centers’ national poison data system (NPDS): 32nd annual report. Clin Toxicol. 2015;53(10):962–1147.

Gilmore D, Zorland J, Akin J, et al. Mortality risk in a sample of emergency department patients who use cocaine with alcohol and/or cannabis. Subst Abuse. 2018;39(3):266–70.

Zahra E, Darke S, Degenhardt L, Campbell G. Rates, characteristics, and manner of cannabis-related deaths in Australia 2000–2018. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;212:108028.

Jones CM, Bekheet F, Park JN, Alexander GC. The evolving overdose epidemic: Synthetic opioids and rising stimulant-related harms. Epidemiol Rev. 2020.

Mitra S, Boyd J, Wood E, et al. Elevated prevalence of self-reported unintentional exposure to fentanyl among women who use drugs in a Canadian setting: A cross-sectional analysis. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;83:102864.

Park JN, Weir BW, Allen ST, et al. Fentanyl-contaminated drugs and non-fatal overdose among people who inject drugs in Baltimore, MD. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15(1):1–8.

Karamouzian M, Papamihali K, Graham B, et al. Known fentanyl use among clients of harm reduction sites in British Columbia, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;77:102665.

Orpana H, Giesbrecht N, Hajee A, Kaplan MS. Alcohol and other drugs in suicide in Canada: opportunities to support prevention through enhanced monitoring. Inj Prev. 2021;27(2):194–200.

Skinner R, McFaull S, Rhodes AE, et al. Suicide in Canada: is poisoning misclassification an issue? Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(7):405–12.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Lawson Greenberg and Mark Stinner at Statistics Canada for their work acquiring the dataset used in this study from the Canadian Vital Statistics Death Database, and their assistance with determining appropriate parameters for the authors’ data request. We would also like to thank Dr. Tim Stockwell at the University of Victoria for his valuable input on determining the parameters for the data request to Statistics Canada.

Funding

SK, PK and EB are employed by the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA). CCSA receives financial contributions from Health Canada. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada. BMH is employed at the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), however was employed by CCSA for the time she worked on the manuscript. MY is employed at GREO (Gambling Research Exchange Ontario), however was also employed by CCSA for the time he worked on the manuscript. AS is partially funded by a CIHR postdoctoral fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SK contributed to the conception and design of the work, analysed, and interpreted the data and wrote the draft. AS contributed to the conception and design of the work, data acquisition and interpretation and critical revision of all drafts. BMH contributed to interpretation of the data and critical revision of all drafts. MY contributed to the conception and design of the work, data acquisition and interpretation, and critical revision of all drafts. PK contributed to the conception and design of the work, data acquisition and interpretation, and critical revision of all drafts. EB contributed to interpretation of the data and critical revision of the drafts. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable, as data were aggregated.

Consent for publication

Not applicable as no individual person’s data are presented.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table 1.

Total counts (n) and percentage (%) of substance use-attributable injury deaths in Canada by region, age group and sex, 2017.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Konefal, S., Sherk, A., Maloney-Hall, B. et al. Polysubstance use poisoning deaths in Canada: an analysis of trends from 2014 to 2017 using mortality data. BMC Public Health 22, 269 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12678-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12678-z