Abstract

Background

Depression is a psychological dysfunction that impairs health and quality of life. However, whether environmental tobacco smoke exposure (ETSE) is associated with depression is poorly understood. This study was designed to evaluate the association of ETSE with depression among non-smoking adults in the United States.

Method

Using the 2015–2016 United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), we identified 2623 adults (females – 64.2%, males – 35.8%) who had never smoked and applied multivariable adjusted-logistic regression to determine the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) at P < 0.05 for the association of ETSE with depression adjusting for relevant confounders.

Results

Mean age of respondents was 46.5 ± 17.9 years, 23.5% reported ETSE, and 4.7% reported depression. Also, aORs for the association of ETSE with depression were 1.992 (1.987, 1.997) among females and 0.674 (0.670, 0.677) among males. When we examined the association by age groups, the aORs were 1.792 (1.787, 1.796) among young adults (< 60 years) and 1.146 (1.140, 1.152) among older adults (≥60 years).

Conclusions

We found that ETSE was associated with higher odds of depression among females but not among males.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Environmental tobacco smoke exposure (ETSE) is the exposure to smoke arising from the burning of any form of tobacco product(s) or exhalation by a person who smokes any form of tobacco product [1, 2]. Several pieces of evidence suggest that ETSE may be a major modifiable risk factor for morbidity and mortality globally [3, 4]. Also, ETSE has been suggested to be associated with productivity losses [5] and responsible for 600,000 deaths per year in the United States (US) [3, 6]. A recent report revealed a decline in the prevalence of tobacco smoking among males and females [7] without itemizing ETSE rates and implications on mental health. Depression is a widespread mood disorder [8, 9] associated with morbidity and mortality worldwide [5]. It affects one out of every five people in a lifetime and is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide [10]. It is characterized by symptoms associated with imbalance(s) in emotional, motivational, cognitive, and physiological wellbeing [10, 11].

Several studies have reported the relationship between smoking and depressive symptoms [8, 12,13,14,15,16,17], which prompted legislative interventions [18, 19] to minimize smoking rates. However, ETSE is an evolving phenomenon worldwide with the potential of making vulnerable populations at odds of adverse health outcomes [20,21,22,23,24]. Some animal studies [25,26,27,28,29] have reported the potential inhibitory effect of ETSE on dopamine transport and metabolism. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter with multiple functions in neurological processes and mental health [30]. For example, dopamine-receptor localization attributable to ETSE [27] has been linked with psychologically-related deformities in rat models [28]. Whether similar exposures can affect mental health in human populations is yet to be clearly understood.

It is not yet clear whether ETSE is associated with alteration(s) that could promote depressive symptoms and/or disorders in the neural network among humans. Understanding the importance of ETSE in depression outcomes could offer useful new information to guide the design of well-articulated public health policies, guidelines or advisory for the effective management of ETSE to avoid depressive symptoms and adverse health conditions.

The current analysis examined the association of ETSE with depression among non-smokers in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). We hypothesized ETSE had a null association with depression and assessed whether the association differed by sex and age in the same population.

Methods

Study design and sampling strategies

We used the 2015–2016 NHANES survey data by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the US for this study [31]. Using a multistage probability technique, 15,327 non-institutionalized civilian residents of the United States across 50 states and Washington DC were sampled, and 9971 completed the interview. Specific subgroups populations were factored into the sampling to increase the consistency and accuracy of estimates in the US population [32].

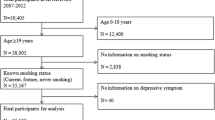

From the 9971 respondents that completed the interview, we excluded respondents less than 18 years (3979) and active smokers (2851), i.e. those who reported they had smoked at least 100-lifetime cigarettes or currently smoke/consume any form of tobacco products or e-cigarette. Also, 518 respondents with missing data (smoking, ETSE and depression status) were excluded from this current analysis. In all, 2623 respondents (958 males and 1665 females) were included in the final analysis of this report. A detailed description of how respondents were selected for the final analysis in this study is presented in Fig. 1.

Definition of depression (outcome)

Using the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) depression scale, respondents provided information on experience(s) and frequency of depressive symptoms in the last two weeks preceding the survey. The PHQ-9 is a 9-item scale designed to probe information on interest or pleasure in doing things, feeling down or hopeless, sleeping problems, etc. Respondents reported whether and how often they experienced depressive symptoms such as; little interest or pleasure in doing things, feeling down or hopeless, sleeping problems, feeling of tiredness or having little energy, etc. Responses to each item on the PHQ-9 scale ranged from ‘not at all’, ‘several days’, ‘more than half the day’ to ‘nearly every day’ with a consecutive score of 0, + 1, + 2 and + 3, respectively. Overall depression score was computed by aggregating the score assigned to each item on the PHQ-9 scale. Details of the criteria for assessment, scoring guide, validation, reliability and efficiency of PHQ-9 has been reported elsewhere [33]. A respondent is classified to be likely undergoing depression if the PHQ-9 score ≥ 10 according to the PHQ-9 scoring guide [33] and some previously published studies [34, 35].

Environmental tobacco smoke exposure – ETSE (exposure)

In the NHANES data, respondents were requested to provide information on whether they had worked at a job or spent time in a restaurant/bar/car/indoor area where someone smoked indoors (at least once) in the last seven days. ETSE was defined as a self-reported exposure to smoke arising from burning any form of tobacco products or exhaling by a smoker [1, 2] in any indoor environment.

Data collection and variables of the study (confounding)

Trained staff collected information on demographic and lifestyle characteristics through in-person interviews using validated survey instruments. Demographic characteristics include; sex (male/female), age in years, and race (Hispanics only/White only/Black only/Others). Education was defined as ≥High School if the respondent reported completing formal education (at least 9th grade) otherwise <High School. Employment status was defined as ‘yes’ the respondent currently engaged in any form of a paid job, otherwise ‘no’. Annual household income was dichotomized as ≤ $24,999 or > $24,999. Marital status was defined as never married, married/living with a partner and widowed/divorced/separated. Alcohol use was defined as ‘yes’ if the respondent took at least 12 drinks of alcoholic drink in the past year or a lifetime, otherwise ‘no’.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were computed at a statistical significance of two-sided P < 0.05 using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY USA). Respondents’ characteristics were stratified by depression status (no/yes) and compared using Chi-square (χ2) test or independent sample t-test for categorical or continuous data, respectively. Multivariable adjusted logistic regression was applied to estimate the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the association of ETSE with depression (adjusting for socio-demographic and lifestyle factors) in the overall sample. We stratified the analysis of the ETSE – depression association by sex (male/female), age groups (younger adults; < 60 years and older adults; ≥60 years), race (Hispanics only, Whites only, Blacks only and Others), employment status (no, yes), annual household income (no, yes), marital status (never married, married and widowed) and alcohol use (no, yes). Also, a likelihood ratio test was carried out to test the significance of the interaction of demographic and lifestyle factors with ETSE in the logistic regression models. All estimates in this report were weighted (using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines) to reduce potential biases attributable to complex sample designs and unequal probabilities in sampling and calibrated to the overall US population (to minimize coverage disparities and reduce variances in estimation techniques) [32].

Results

Characteristics of non-smoking adults in the 2015–2016 NHANES survey data

Characteristics of respondents are presented in Table 1. Overall, the mean age was 46.5 ± 17.9 years, and 63.4% of respondents in this study were females. Also, 58.8% of the respondents were Whites, 3.5% had at least a high school education and more than half (65.3%) were currently employed. The majority (83.5%) of the respondents had an annual household income of more than $24,999, and 17.4% were never married. Similar distributions were observed for the age-stratified analyses (Tables 2 & 3), but 86.4% and 30.0% of young and old adults, respectively, were employed. The proportions of widowed respondents were 15.5%, 8.2% and 36.0% in the overall sample, among young and old adults, respectively.

Prevalence of ETSE among non-smoking adults in the 2015–2016 NHANES survey data

Overall, 23.5% of the entire sample reported ETSE (Fig. 2A). Also, the proportion of respondents who reported ETSE among young adults (24.9%) was significantly higher (P < 0.0001) than their counterparts among old adults (19.4%).

Prevalence of and factors associated with depression among non-smoking adults in the 2015–2016 NHANES survey data

Overall, 4.7% of the entire sample reported having depression (Fig. 2B), with a significantly higher proportion among old adults (5.0%), females (5.7%), among those unemployed (7.7%), among low-income households (11.4%) and alcohol users (4.7%) – Table 1. Age-stratified analysis revealed a similar trend predominantly among young adults.

Furthermore, females had 1.9 times higher odds of being depressed; aOR: 1.898 (1.893, 1.903) compared to males (Table 4). Also, Whites only; aOR: 0.764 (0.762, 0.767) and Blacks only; aOR: 0.643 (0.641, 0.645) had lesser odds of being depressed compared to Hispanics only. Similarly, those who were employed (compared to those unemployed); aOR: 0.479 (0.478, 0.480) and respondents from households with income greater than $24,999 (compared with those from households with an annual income of less than $24,999); aOR: 0.361 (0.360, 0.362) had lesser odds of being depressed. Similar trends were observed across sex and age groups (Tables 5, 6 & 7), but Whites only; aOR: 3.657 (3.606, 3.708) and Blacks only; aOR: 5.503 (5.429, 5.579) had higher odds of being depressed compared to Hispanics only among old adults. Also, respondents who are married; aOR: 7.328 (7.225, 7.434) and widowed; aOR: 11.730 (11.561, 11.901) had higher odds of being depressed compared to those who were never married among old adults. Those who reported alcohol use had 1.7 times higher odds of being depressed; aOR: 1.733 (1.729, 1.737) than those who do not take alcohol. The results were largely unaltered after stratifying the analyses by sex (Table 5).

ETSE and depression among non-smoking adults in the 2015–2016 NHANES survey data

Overall, the prevalence of depression among respondents with ETSE (7.0%) was significantly higher compared to those without ETSE (4.0%) (Fig. 2C). A similar trend was observed after stratifying by age.

Overall (Table 4), respondents exposed to ETSE had 1.6 times higher odds of being depressed; aOR: 1.625 (1.622, 1.629) compared to those unexposed to ETSE in the overall sample. Similarly, young adults exposed to ETSE had 1.7 times higher odds of being depressed; aOR: 1.792 (1.787, 1.796) compared to similar respondents unexposed to ETSE.

Subgroup analyses of the association of ETSE with depression

The association of ETSE with depression was stratified by sex, age groups, race, employment status, annual household income and alcohol use (Table 8), and remained independent of age groups, employment status, annual household income and alcohol use. However, aORs for the association of ETSE with depression was 1.992 (1.987, 1.997) among females and 0.674, (0.670, 0.677) among males P for interaction < 0.0001. Also, aORs for the association of ETSE with depression was aOR: 0.552 (0.549, 0.556) among Blacks only, 1.410 (1.403, 1.417) among Hispanics only and 1.646 (1.641, 1.652) among Whites only P for interaction < 0.0001. Similarly, aOR of the association of ETSE with depression was 1.772 (1.766, 1.779) among those who have never married only, 2.285 (2.278, 2.292) among married subjects only and 0.403 (0.400, 0.405) for those who are widowed P for interaction < 0.0001.

Discussion

The current study provides evidence for the association of ETSE with depression in the 2015-2016 NHANES data from the US. First, the rates of ETSE was relatively high. Second, depression was relatively prevalent. Third, females and young adults exposed to ETSE were at higher odds of being depressed. However, males exposed to ETSE were not at higher odds of being depressed.

Several reports [7, 12, 16, 36, 37] have attempted to present evidence on the burden of smoking in different populations with limited information on ETSE rates. In our study, we found about two in every ten non-smokers reported ETSE. Our findings on the burden of ETSE among non-smokers were comparable to a nationally representative tobacco survey among never-smoking youths from 168 countries between 1999 and 2008 [38]. In that study, about 23% of never-smoking youth were secondarily exposed to tobacco. In contrast, findings from a similar population in other climes revealed ETSE was as high as over 70% in China [39] and Spain [40]. Despite the recent decline in tobacco use, ETSE remains a potential threat to public health [41], and continuous efforts to reduce the burden of ETSE is vital. Globally, daily smoking rates appear lower, but the number of people using tobacco has increased [7]. In principle, passive exposure to tobacco smoke among non-smokers remains a public health threat in most regions of the world [42,43,44,45] and has been reported as a leading cause of death in the US [46]. However (in the light of our findings), evidence-based intervention efforts are necessary not only to meet reduction targets to manage the escalating burden of morbidity and mortality attributable to tobacco use but also ETSE. Also, more studies evaluating the potential contributions of ETSE to specific causes of morbidity/mortality are necessary.

In our study, the proportion of respondents with ETSE was significantly higher among young adults than old adults. Similarly, we found respondents exposed to ETSE at higher odds of being depressed in the overall population with aggravated odds among young adults and females. Our findings are in tandem with similar reports [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54], where ETSE was observed to be associated with odds of psychological/mental distress. In contrast, other reports [47, 55, 56] found no significant association between ETSE and depression. These results can be explained in several ways.

First, ETSE is a proxy for discerning stressful living conditions [57, 58]. It may imply respondents exposed to ETSE might have been subjected to living and working conditions that predispose them to depression. In tandem with this assertion, lesser odds of depression and higher tendencies of a healthier lifestyle have been reported among persons from homes where smoking is prohibited [59]. Also, a diathesis-stress model has posited the association of ETSE with depression might be a function of stress [60]. Susceptibilities to the stressful environment (which may be evident by ETSE) may promote stress-induced depressive symptoms.

Second, the ETSE-depression relationship may be plausible. Using animal models, a neuro-biological route (via the dopamine complex assembly) has been reported for the causal association between ETSE and depression [25,26,27,28,29]. For example, caudate-putamen localization of dopamine D1 and D2 receptors was observed in rats with ETSE [27]. Similarly, alterations in the magnitude of dopamine D1 and γ-aminobutyric acid β2 receptors in the caudate-putamen may up-regulate dopamine transporter mRNA expression to promote neuropsychological disorders related to the midbrain abnormalities in rats [28]. Also, ETSE was observed to inhibit dopamine reuptake in the in-vivo [26], and low dopamine activity was associated with increased odds of major depressive disorders [61].

Contrary to the expectation, we found ETSE was inversely associated with depression among males. Our findings were in tandem with a report in Germany [55] highlighting a similar observation among males. On the one hand, suggesting high exposure to ETSE is likely to be associated with lower odds of being depressed (independent of sex, race and marital status) would be implausible. On the other hand, it is tedious to hypothesize that the latent noxious effect of ETSE on depression might be counteracted by an unknown factor(s) primarily related to social livelihood and systems patronizing males more than females. First, some reports [20, 55, 62] have suggested that females are likely to be vulnerable to ETSE from family members and colleagues who smoke at home and the workplace. Second, sex-related hormonal difference(s) that accompany mechanistic change(s) in the pathophysiology of diseases [63] is a plausible explanation for the difference in odds of depression between males and females in this study. In tandem with this postulation, gender-related differences have been reported in the onset of depression events in the entire life course [64]. Similarly, a correlation between the prevalence of depression and hormonal changes (during puberty, pregnancy, and perimenopause) has been hypothesized among females [65]. However, this observation does not connote the simplification of the potential effects of ETSE on the odds of being depressed among males. Future studies might consider discerning underlying genetic differences that confer different response(s) to depression in the light of ETSE.

Some limitations in this study are worth mentioning. The cross-sectional method excludes causal interpretations for the ETSE-depression relationship. ETSE was self-reported. It would be necessary to clarify the significance of the magnitude and duration of ETSE in future studies. The possibility of ETSE as an indicator for poor living conditions cannot be ruled out. Depression is likely to have been subjectively estimated given that it was self-reported and not a physician-administered assessment. Also, data on proximal drivers of depression (such as; living conditions, emotional stressors, coping and/or adapting mechanisms, etc.) were unaccounted for in our study. Howbeit, our data source and methodologies greatly enhanced the quality and reliability of our data. Hence, the main conclusions of this study remain valid and largely unaffected in the light of the large sample size, sampling strategy, statistical adjustment for potential confounding factors and weighting, which improved the statistical power of the study to be representative of the US population. Future longitudinal studies are essential to determine the causal association between ETSE and depression.

Conclusion

Females exposed to ETSE (compared to those unexposed) were at higher odds of being depressed, but males exposed to ETSE were not at higher odds of being depressed. Intervention efforts targeted at policy formulation and behavioural change should be directed at tobacco control and the prevention of ETSE.

Availability of data and materials

Data for this study were sourced from the 2015–2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) of the United States. The NHANES data was provided by the Center for Disease Control of the United States. It is open and publicly accessible through the following link; https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

Abbreviations

- aOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CDC:

-

Centre for disease control and prevention

- NHANES:

-

National health and nutrition examination survey

- ETSE:

-

Environmental tobacco smoke exposure

- US:

-

United States

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient health questionnaire

References

Institute of Medicine. Secondhand smoke exposure and cardiovascular effects: making sense of the evidence. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010. 240 p.

Services UDoHaH. The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress: a Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta GA US: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Department of Health and Human Services; 2014 January 2014. Contract No.: V 137.

WHO. Who Report On The Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2011. In: Warning about the dangers of tobacco. Italy: World Health Organization; 2011. p. 152.

Navas-Acien A. Global tobacco use: old and new products. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(Supplement_2):S69–75.

Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses--United States, 2000–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(45):1226–8.

WHO. Who Report On The Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2013 Enforcing bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship. Luxembourg: World Health Organization; 2013. p. 202.

Ng M, Freeman MK, Fleming TD, Robinson M, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Thomson B, et al. Smoking prevalence and cigarette consumption in 187 countries, 1980-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(2):183–92. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.284692.

Audrain-McGovern J, Leventhal AM, Strong DR. Chapter Eight - The Role of Depression in the Uptake and Maintenance of Cigarette Smoking. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2015;124:209-243. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.irn.2015.07.004.

Shahpesandy H. Different manifestation of depressive disorder in the elderly. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2005;26(6):691–5.

Ménard C, Hodes GE, Russo SJ. Pathogenesis of depression: insights from human and rodent studies. Neuroscience. 2016;321:138–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.053.

Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(3):249–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/58.3.M249.

Bakhshaie J, Zvolensky MJ, Goodwin RD. Cigarette smoking and the onset and persistence of depression among adults in the United States: 1994–2005. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;60:142–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.10.012.

Goodwin RD. Next steps toward understanding the relationship between cigarette smoking and depression/anxiety disorders: a Lifecourse perspective. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;19(1):1–2. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntw296.

Mathew AR, Hogarth L, Leventhal AM, Cook JW, Hitsman B. Cigarette smoking and depression comorbidity: systematic review and proposed theoretical model. Addiction. 2017;112(3):401–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13604.

Park S, Romer D. Associations between smoking and depression in adolescence: an integrative review. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2007;37(2):227–41. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2007.37.2.227.

Ruggles KV, Fang Y, Tate J, Mentor SM, Bryant KJ, Fiellin DA, et al. What are the patterns between depression, smoking, unhealthy alcohol use, and other substance use among individuals receiving medical care? A longitudinal study of 5479 participants. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(7):2014–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1492-9.

Breslau N, Peterson EL, Schultz LR, Chilcoat HD, Andreski P. Major depression and stages of smoking. A longitudinal investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(2):161–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.55.2.161.

Anastasiou E, Feinberg A, Tovar A, Gill E, Ruzmyn Vilcassim MJ, Wyka K, et al. Secondhand smoke exposure in public and private high-rise multiunit housing serving low-income residents in New York City prior to federal smoking ban in public housing, 2018. Sci Total Environ. 2020;704:135322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135322.

Martinez-Donate AP, Johnson-Kozlow M, Hovell MF, Gonzalez Perez GJ. Home smoking bans and secondhand smoke exposure in Mexico and the US. Prev Med. 2009;48(3):207–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.12.011.

Lee B-E, Ha E-H. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke among south Korean adults: a cross-sectional study of the 2005 Korea National Health and nutrition examination survey. Environ Health. 2011;10(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-10-29.

Lee KA, Palipudi KM, English LM, Ramanandraibe N, Asma S. Secondhand smoke exposure and susceptibility to initiating cigarette smoking among never-smoking students in selected African countries: findings from the Global youth tobacco survey. Prev Med. 2016;91:S2–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.04.017.

Okekunle AP, Asowata JO, Adedokun B, Akpa OM. Secondhand smoke exposure and dyslipidemia among non-smoking adults in the United States. Indoor Air. 2021;00:1– 10. https://doi.org/10.1111/ina.12914.

Akpa OM, Okekunle AP, Asowata JO, Adedokun B. Passive smoking exposure and the risk of hypertension among non-smoking adults: the 2015–2016 NHANES data. Clin Hypertens. 2021;27(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40885-020-00159-7.

Lange S, Koyanagi A, Rehm J, Roerecke M, Carvalho AF. Association of Tobacco use and Exposure to secondhand smoke with suicide attempts among adolescents: findings from 33 countries. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;22(8):1322–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntz172.

Fà M, Carcangiu G, Passino N, Ghiglieri V, Gessa GL, Mereu G. Cigarette smoke inhalation stimulates dopaminergic neurons in rats. Neuroreport. 2000;11(16):3637–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001756-200011090-00047.

Carr LA, Basham JK, York BK, Rowell PP. Inhibition of uptake of 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion and dopamine in striatal synaptosomes by tobacco smoke components. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;215(2–3):285–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2999(92)90040-B.

Naha N, Li SP, Yang BC, Park TJ, Kim MO. Time-dependent exposure of nicotine and smoke modulate ultrasubcellular organelle localization of dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in the rat caudate-putamen. Synapse. 2009;63(10):847–54.

Li S, Kim KY, Kim JH, Kim JH, Park MS, Bahk JY, et al. Chronic nicotine and smoking treatment increases dopamine transporter mRNA expression in the rat midbrain. Neurosci Lett. 2004;363(1):29–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2004.03.053.

Bahk JY, Li S, Park MS, Kim MO. Dopamine D1 and D2 receptor mRNA up-regulation in the caudate-putamen and nucleus accumbens of rat brains by smoking. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26(6):1095–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-5846(02)00243-9.

Berridge KC. The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: the case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191(3):391–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-006-0578-x.

CDC. NHANES 2015–2016 Procedure Manuals US: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2016 [updated 2/21/2020; cited 2020 05 May]. Available from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/ContinuousNhanes/Default.aspx?BeginYear=2015.

Chen TCCJ, Riddles MK, Mohadjer LK, Fakhouri THI. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2015–2018: Sample design and estimation procedures. United States: U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics, Statistics NCfH; 2020. Contract No.: DHHS Publication No. 2020–1384

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

Nguyen B, Weiss P, Beydoun H, Kancherla V. Association between blood folate concentrations and depression in reproductive aged U.S. women, NHANES (2011–2012). J Affect Disord. 2017;223:209–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.019.

Wang Y, Lopez JMS, Bolge SC, Zhu VJ, Stang PE. Depression among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus, US National Health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES), 2005–2012. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0800-2.

Tjora T, Hetland J, Aarø LE, Wold B, Wiium N, Øverland S. The association between smoking and depression from adolescence to adulthood. Addiction. 2014;109(6):1022–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12522.

Lee K-J. Current smoking and secondhand smoke exposure and depression among Korean adolescents: analysis of a national cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2):e003734. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003734.

Veeranki SP, Mamudu HM, Zheng S, John RM, Cao Y, Kioko D, et al. Secondhand smoke exposure among never-smoking youth in 168 countries. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(2):167–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.014.

Xiao L, Yang Y, Li Q, Wang C-X, Yang G-H. Population-based survey of secondhand smoke exposure in China. Biomed Environ Sci. 2010;23(6):430–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-3988(11)60003-2.

Lushchenkova O, Fernández E, López MJ, Fu M, Martínez-Sánchez JM, Nebot M, et al. Secondhand smoke exposure in Spanish adult non-smokers following the introduction of an anti-smoking law. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2008;61(7):687–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1885-5857(08)60205-4.

Hipple Walters B, Petrea I, Lando H. Tobacco control in low- and middle-income countries: changing the present to help the future. J Smok Cessat. 2018;13(4):187–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsc.2018.4.

Zvolensky MJ, Taha F, Bono A, Goodwin RD. Big five personality factors and cigarette smoking: a 10-year study among US adults. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;63:91–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.02.008.

Yang JJ, Yu D, Wen W, Shu X-O, Saito E, Rahman S, et al. Tobacco smoking and mortality in Asia: a pooled meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e191474-e.

Jha P, Hill C, Wu DCN, Peto R. Cigarette prices, smuggling, and deaths in France and Canada. Lancet. 2020;395(10217):27–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31291-7.

Allen LN, Nicholson BD, Yeung BYT, Goiana-da-Silva F. Implementation of non-communicable disease policies: a geopolitical analysis of 151 countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(1):e50–e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30446-2.

Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–45. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.10.1238.

Lam E, Kvaavik E, Hamer M, Batty GD. Association of secondhand smoke exposure with mental health in men and women: cross-sectional and prospective analyses using the UK health and lifestyle survey. Eur Psychiatry. 2013;28(5):276–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2012.04.001.

Michal M, Wiltink J, Reiner I, Kirschner Y, Wild PS, Schulz A, et al. Association of mental distress with smoking status in the community: results from the Gutenberg health study. J Affect Disord. 2013;146(3):355–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.09.019.

Patten SB, Williams JVA, Lavorato DH, Woolf B, Wang JL, Bulloch AGM, et al. Major depression and secondhand smoke exposure. J Affect Disord. 2018;225:260–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.006.

Hamer M, Stamatakis E, Batty GD. Objectively assessed secondhand smoke exposure and mental health in adults: cross-sectional and prospective evidence from the Scottish health survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(8):850–5. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.76.

Bandiera FC, Arheart KL, Caban-Martinez AJ, Fleming LE, McCollister K, Dietz NA, et al. Secondhand smoke exposure and depressive symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(1):68–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181c6c8b5.

Jacob L, Smith L, Jackson SE, Haro JM, Shin JI, Koyanagi A. Secondhand smoking and depressive symptoms among in-school adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58(5):613–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.12.008.

Wellman RJ, Wilson KM, O’Loughlin EK, Dugas EN, Montreuil A, O’Loughlin J. Secondhand smoke exposure and depressive symptoms in children: a longitudinal study. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2018;22(1):32–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nty224.

Nakata A, Takahashi M, Swanson NG, Ikeda T, Hojou M. Active cigarette smoking, secondhand smoke exposure at work and home, and self-rated health. Public Health. 2009;123(10):650–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2009.09.006.

Erdsiek F, Brzoska P. Association between second-hand smoke exposure and depression and its moderation by sex: findings from a nation-wide population survey in Germany. J Affect Disord. 2019;253:102–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.081.

Bot M, Vink JM, Willemsen G, Smit JH, Neuteboom J, Kluft C, et al. Exposure to secondhand smoke and depression and anxiety: a report from two studies in the Netherlands. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75(5):431–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.08.016.

Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1(1):293–319. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938.

Bandiera FC. What are candidate biobehavioral mechanisms underlying the association between secondhand smoke exposure and mental health? Med Hypotheses. 2011;77(6):1009–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2011.08.036.

Pahl K, Brook JS, Koppel J, Lee JY. Unexpected benefits: pathways from smoking restrictions in the home to psychological well-being and distress among urban black and Puerto Rican Americans. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(8):706–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr062.

Patten SB. Major depression epidemiology from a diathesis-stress conceptualization. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-19.

Belujon P, Grace AA. Dopamine system Dysregulation in major depressive disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20(12):1036–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyx056.

Park YS, Lee C-H, Kim Y-I, Ahn CM, Kim JO, Park J-H, et al. Association between secondhand smoke exposure and hypertension in never smokers: a cross-sectional survey using data from Korean National Health and nutritional examination survey V, 2010–2012. BMJ Open. 2018;8(5):e021217. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021217.

Rosano GM, Spoletini I, Vitale C. Cardiovascular disease in women, is it different to men? The role of sex hormones. Climacteric. 2017;20(2):125–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2017.1291780.

Salk RH, Hyde JS, Abramson LY. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(8):783–822. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000102.

Albert PR. Why is depression more prevalent in women? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015;40(4):219–21. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.150205.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to appreciate the Center for Disease Control and Prevention United States’ efforts to make the data for this report publicly available.

Funding

The Brain Pool Program supported this work through the National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (2020H1D3A1A04081265). The funding body played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OMA and APO conceptualized and designed the study; JOA and APO conducted the data acquisition, curation, analysis and interpretation; OMA contributed to the data analysis and interpretation; APO and JOA drafted the manuscript; JEL and OMA critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The survey protocols were approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Ethics Review Board of the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention of the United States.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Okekunle, A.P., Asowata, J.O., Lee, J.E. et al. Association of Environmental tobacco smoke exposure with depression among non-smoking adults. BMC Public Health 21, 1755 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11780-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11780-y