Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study is to assess the status of physical body indices such as body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC), and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) among the older adults aged 45 and above in India. Further, to explore the association of anthropometric indices with various non-communicable morbidities.

Methods

The study uses secondary data of the Longitudinal Ageing Survey’s first wave in India (2017–18). The national representative sample for older adults 45 and above (65,662) considered for the analysis. The prevalence of the non-communicable diseases (NCDs) included in the study is based on the self-reporting of the participants. Diseases included are among the top ten causes of death, such as cancer, hypertension, stroke, chronic heart diseases, diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases, and multi-morbidity. Multi-morbidity is a case of having more than one of the morbidities mentioned above. BMI-obese indicates an individual having a BMI ≥30, and the critical threshold value for high-risk WC for men is ≥102 cm while for women is ≥88 cm. The critical limit for the high-risk WHR for men and women is ≥0.90 and ≥ 0.85, respectively. Descriptive statistics and multiple logistic regressions are used to assess the association BMI, WC, and WHR with non-communicable morbidities.

Results

Based on the multivariate-adjusted model, odds shows that an Indian older adult aged 45 and above is 2.3 times more likely (AOR: 2.33; 95% CI (2.2, 2.5)) by obesity, 61% more likely (AOR: 1.61; 95% CI (1.629, 1.631)) by high-risk WHR and 98% more likely (AOR: 1.98; 95% CI (1.9, 2.1)) by high-risk WC to develop CVDs than their normal counterparts. Similarly, significant positive associations of obesity, high-risk WC, and high-risk WHR were observed with other NCDs and multi-morbidity.

Conclusion

Our study shows that obesity, high-risk WC, and high-risk WHR are significant risks for developing NCDs and multi-morbidity among the older adults in India. There is a need for a multi-sectoral approach to reduce the share of the elderly population in high-risk groups of BMIs, WHR, and WC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ageing is a natural phenomenon that is inevitable with any demographic transition. Although all the countries across the globe are facing the ageing of the population, they may differ in the pace of ageing. The share of the aged population in developed nations is already quite high, whereas the developing nations have now started facing an accelerated ageing population’s challenges. In 2019, the global population consisted of 703 million persons aged 65 or above, which is projected to be 1.5 billion in 2050 [1]. The pace of population ageing has been fastest in southeastern Asia. According to the Census 2011, 8.6% of India’s population was aged 60 or above, accounting for 103 million elderly people [2]. It has been projected that the size of the elderly population of India will rise to 319 million in 2050, 20% share of the total population. Rapid population ageing can be seen as the consequences of medical advancements and better health facilities that stretched the longevity of human life. The increasing life expectancy also possesses a higher risk of major health issues with increasing disability and illness [3, 4]. The aged population is expected to have a long healthy life despite a long life that corresponds to the concept of healthy or successful ageing.

As the epidemiological transition occurs in most developing countries, including India, the shifting of burden towards non-communicable disease (NCDs) will affect mainly the older population [5]. In India, along with non-communicable ailments, communicable diseases also mount older people’s burden [6]. In a study conducted in India by WHO-SAGE, it was found that around half of the older population suffers from at least one chronic disease. Hence, NCDs are more prevalent in the older population [7]. The majority of NCDs are associated with the human lifestyle. Inappropriate dietary intake, lack of physical exercise, tobacco and alcohol consumption, high body mass index, and obesity are the factors that affect the health of the person and increases the risk of NCDs [5]. Chronic diseases caused by a person’s lifestyle are the leading cause of death in India [8]. The lifestyle diseases such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), stroke, diabetes, hypertension etc., can be associated with a sedentary lifestyle lacking physical activities and an unhealthy way of living. Such lifestyle diseases are the leading cause of preventable mortality worldwide.

Obesity is found to be the major cause of NCDs. It is defined as an abnormal accumulation of body fat, i.e., greater than 20% of an individual’s ideal body weight [9]. In older people, obesity is associated with the early onset of morbidities and later functional disabilities contributing to premature mortality [10]. According to WHO, the prevalence of obesity is tripled between 1975 to 2016 [11]. In addition to this, around 2.8 million people die each year, and an estimated global DALYs of 35.8 million is caused by overweight and obesity [12]. This is a grave scenario of concern as many severe and life-threatening diseases such as type II diabetes, heart failure, Mellitus, hyperlipidaemia, and breast cancer are linked with obesity. It increases the risk of colon cancer, coronary heart disease, infertility etc. [13, 14].

The body mass index (BMI) is an index usually used for determining whether a person has excess weight or not. It is the measure that considers the weight and height of an individual and is defined as an individual’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of his/her height in meter (kg/m2). A person is considered to be overweight or obese based on BMI value, but this index may not correspond to the same mark of fatness in different people. BMI is a traditional indicator and is not a sensitive index as it cannot recognize the fat distribution, high-fat percentage, and the increment of the muscles [15]. There are other anthropometric measures that capture obesity more precisely than the BMI index. Waist circumference, hip circumference, and waist-hip ratio are few indices that can be used as an alternative to BMI. These indices can reflect abdominal adipose, a superior measure for the risk of various NCDs, including CVD. The idea of using the WHR as a proxy arose from a cohort study, which presented that the Waist hip ratio is associated with an increased risk of stroke, ischemic heart diseases, and premature death [16]. Among women, the WHR showed a significant positive association with myocardial infection, stroke, angina pectoris, and death [17]. However, evidence suggests that WC can also be used to measure CVD risk factors [18] and overall weight management [19].

The Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) has created a window of opportunity for scientific investigation of health, economic, social determinants, and consequences of population ageing in India. The present study focuses on various anthropometric measures, including BMI, WHR, WC, and their association with NCDs among the elderly in India. LASI provides nationally representative information on the measured anthropometric indices among the elderly in India. For the first time, it has included measures such as WC and WHR. The primary objective of this study is to estimate the prevalence of the described anthropometric indices among the elderly in India. This study’s second objective is to explore the association of these indices with selected chronic health conditions among the elderly population in India.

Methods

Data used in the current study is collated from the First Wave of the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) conducted during 2017–18. The LASI is a full-scale national survey of scientific investigation of the health, economics, and social determinants and consequences of population ageing in India. A multistage stratified area probability cluster sampling design was used in LASI to select the observational units. A three and four-stage sampling design has been adopted for rural and urban areas, respectively. A household with at least one respondent aged 45 and above has been selected as a sample from all the states and UTs of India except Sikkim [20]. The survey covered 65,562 older adults age 45 and above. The data collection was completed using CAPI-based schedules conducted by a trained interviewer. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai, was the nodal agency that supervised and monitored the data quality and collection process [20]. The survey recorded the self-reported prevalence of diagnosed chronic morbidities and directly examined anthropometric measures, including weight and height as well as waist and hip circumference of the participants.

Variables

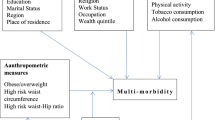

The primary outcome variables of our study are the prevalence of self-reported non-communicable lifestyle diseases, including cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), chronic respiratory diseases, diabetes, cancer, and a combination of two or more aforementioned underlying conditions. CVDs include hypertension, heart diseases and/or stroke, while chronic respiratory diseases include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma and/or bronchitis. All the included NCDs have a dichotomous response by the respondent having diseases as “yes” whereas not having “no”. The explanatory variables used are age, place of residence, sex, marital status, living arrangement, religion, caste, years of schooling, work status, monthly per capita consumption expenditure (MPCE quintile), and geographical regions [21,22,23].

The age has categorized into three categories youngest old, “45–59”, middle old, “60–74” and the oldest old, “75 and above”. Place of residence was divided as usually into rural and urban. We also have constructed variable region as per Indian states geographical area into East, North, Eastern, Central, North-east and West. The respondent marital status divides into Currently married, Widowed, and divorce/separated/others. The older adults living arrangement is also an important factor categorized as living alone, living with spouse or other, living with spouse and children, living with children and others and living with others only. Work status is also important covariate that define in the context of socioeconomic status and also directly or indirectly confound the effect of physical and mental health of a person. It categorized status as “currently working”, “worked in the past but not currently”, and “never worked”. Our study has also considered wealth indicator as MPCE quintile, which categories into five quintiles from poorest to richest. Further, this study includes behavioural health risk factors such as physical activity (includes moderate and vigorous activities), ever smoking or smokeless tobacco (cigarette, bidi, cigar, hookah, cheroot, chewing tobacco, gutka, pan masala,) and ever drinking beverages (beer, wine, liquor, country liquor). Finally, the main independent factors for analysis are Biological risk factors such as BMI, WC and WHR of the individuals.

BMI is a widely used indicator of obesity and the balance between energy intake and energy expenditure, while WC as well as WHR are the indicator of abdominal obesity [24]. BMI is calculated as the ratio of weight (in kg) and the square of height (in m). Based on the WHO classification, BMI levels are classified as underweight (≤18.4), normal (18.5 to 24.9), overweight (25 to 29.9), and obese (≥30) [25]. Similarly, WHO categorizes waist to hip ratio (waist circumference in cm/hip circumference in cm) into low and high-risk levels for men and women separately. Critical limit classification for the high-risk WHR for men is ≥0.90 and for women is ≥0.85. The critical threshold value for high-risk WC for men and women is ≥102 cm and ≥ 88 cm, respectively [25].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses are performed using the STATA-15. First of all, we computed the prevalence of overweight and obesity, low and high risk- WC and WHR among older adults age 45 and above in India. Descriptive statistics are used to systematically examine how the prevalence of self-reported underlying conditions varies across different demographic and socio-economic sub-groups and physical body indices. Also, we applied the chi-square test to measure the degree of association between outcome and explanatory variables. Finally, we fit multiple logistic regression models to examine the adjusted effects of biological risk factors on the prevalence of self-reported single or multi-morbidity conditions. Models are adjusted for age, sex, years of schooling, work status, place of residence, caste, wealth quintile, geographic region, physical activity status and smoking, and drinking behaviours.

Results

Table 1 shows the weighted proportions of the BMI category by different background characteristics among older adults aged 45 and above. The overall prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity among older adults aged 45 and above is 20.64, 20.65 and 7.38%, respectively. The prevalence of obesity was lowest among the individuals aged 75 and above (2.57%) as compared to those aged 45–59 (8.13%) and 60–74 (6.26%). Almost 15% of the urban older adults were obese, while the proportion of obesity among rural older adults was approximately 4%. We can also see cross-region variations; the proportion of individuals who were obese was highest in southern India (12.36%), while it was lowest in the East Indian states (4%).

Table 2 represents the prevalence of WC and WHR across different socio-demographic groups among individuals aged 45 and above in India. Approximately 26% of older adults aged 45 and above had a high-risk WC, and 77.25% had a high risk of WHR. Extreme gender-differences are visible in the prevalence of high-risk WC, with almost 40% of females having a high-risk WC in contrast with 9% of males. 41% of older adults living the urban areas had a high-risk WC, whereas 19% of rural older adults were in the high-risk WC category. Similarly, in the case of the high-risk WHR, the prevalence was slightly higher in the individuals aged 75 and above (77.55%) in comparison to its counterparts. In contrast with the high-risk WC situation, no apparent gender differences were visible in the high-risk WHR prevalence. 76% of males had a high-risk WHR, while 78.3% of females were in the high-risk category of WHR.

Table 3 depicts the weighted proportions of self-reported ever-diagnosed NCDs across different socio-demographic groups among individuals aged 45 and above. Approximately 29% of individuals aged 45 and above had a CVD. The overall prevalence of chronic respiratory disease, diabetes, and cancer in the study sample was 6.5, 12.3, and 0.6%, respectively. 12.5% of older adults self-reported multi-morbidity, i.e., they had two or more NCDs. The prevalence of CVDs was highest in the individuals aged 75 and above (37.5%) compared to individuals aged 45–59 (23.1%) and 60–74 (34%). Likewise, the proportion of persons having a chronic respiratory disease (10.2%), cancer (0.7%), and multi-morbidity (16.2%) was highest in the persons aged 75 and above. 24% of rural adults had any CVD, while the prevalence of CVDs was 40% among urban adults. The proportion of older adults having multi-morbidity was highest among the individuals in the richest quintile of wealth (20.1%).

Table 4 represents the bivariate analysis results showing the association of Physical body Indices and self-reported ever-diagnosed NCDs. Results show that the prevalence of NCDs increases as we go higher in the BMI category. The proportion of older adults having CVDs, chronic respiratory disease, diabetes, and multi-morbidity was highest in the older adults belonging to the obese BMI category, 52.3, 9.7, 27.5, and 27.4%, respectively. Similarly, positive associations of physical body indices and NCDs were visible in the case of both WC and WHR. The prevalence of CVDs (44.4%, p < 0.01), diabetes (22%, p < 0.01), cancer (0.8%, p < 0.01), and multi-morbidity (21.1%, p < 0.01) were higher among older adults with a high-risk WC. Likewise, a higher proportion of individuals having a high-risk WHR were having CVDs (30.8%, p < 0.01), diabetes (13.6%, p < 0.01), cancer (0.7%, p < 0.01), and multi-morbidity (13.4%, p < 0.01) as compared to those in the low-risk category of WHR.

Table 5 shows the multiple logistic regression results, depicting the association of BMI, WC, and WHR with NCDs. As per existing literatures, ageing effect as a universal confounder and with other background confounding factors like sex, schooling level, work status, residence, caste, wealth quintile, region, physical activity status, ever smoking, and drinking status; therefore, we have adjusted the regression results by aforementioned covariates. Overall, BMI had a positive association with NCDs. The likelihood of CVDs was more than two times among the BMI-obese than the BMI-normal population (AOR: 2.31, 95% CI: 2.1–2.5). The possibility of chronic respiratory disease was more among people with abnormal BMI. The BMI-underweight population was about 50% more likely to have Chronic Respiratory Diseases (CRD) than the BMI-normal population (AOR: 1.53, 95% CI: 1.4–1.7). Likewise, results showed a higher likelihood of diabetes (AOR: 1.90, 95% CI: 1.70–2.10) and multi-morbidity (AOR: 2.37, 95% CI: 2.00–2.80) among BMI-obese people than BMI-normal people. However, cancer was not significantly associated with the BMI category.

Individuals in the high-risk category of WHR had more risk of having CVDs, diabetes, and multi-morbidity than those having low-risk WHR; (AOR: 1.61, 95% CI: 1.50–1.70), (AOR: 2.27, 95% CI: 2.10–2.50), and (AOR: 1.61, 95% CI: 1.50–1.70) respectively. The WC-high-risk population was almost 100% more likely to have CVDs than the WC-low-risk population (AOR: 1.98, 95% CI: 1.90–2.10). Similarly, people with high-risk WC had more likelihood of having CRD, diabetes, and multi-morbidity than low-risk WC.

Discussion

The present study provides the current scenario of obesity among the elderly in India. Around 21 and 7% of the elderly population in India aged 45 or above are overweight and obese, respectively. The elderly population belonging to an urban area and upper socio-economic groups has a higher prevalence of obesity than its counterparts, and it remains consistent with previous evidence [26]. Obesity is considered to be a major risk factor for developing several cardiovascular diseases [27]. A considerable share of the elderly population is still obese in India, keeping them at high risk of various chronic morbidities. Results indicate that the prevalence of obesity varies significantly across different socio-economic and demographic strata in India. WHR and WC have been considered as better proxy measures for quantifying obesity and fat distribution [28]. It is also viewed as a risk factor for different chronic diseases [29]. The results for WHR suggest that a very large proportion of the elderly population stands in the high-risk group for developing chronic diseases and multi-morbidity. Every fourth elderly in India is in the high-risk group based on the measured WC, where females are at higher risk compared to males. The proportion of the high-risk group according to the WHR and WC is greater among elderly belonging to upper socio-economic groups and urban area.

One of the possible negative confounding factors for obesity and NCDs comes from daily behavioural factors such as smoking, alcohol, and physical inactivity [30,31,32,33]. These factors have shown strong association with chronic diseases and obesity. Therefore, we have adjusted all these factors in regression models where physical inactivity plays a significant role in adjusting the entire model, among other behavioural factors.

Several studies in different socio-cultural settings have reported that individuals with the BMI range in the obese or overweight counterparts were at a higher risk of developing heart diseases, hypertension, stroke, CVDs and diabetes than the normal-BMI person [34,35,36,37,38]. The current study also reflected the same results. In addition to this, BMI-Obesity, high-risk WC and high risk of WHR, all are a significantly develop risk for CVDs among older adults, which were found inconsistent result in various countries study [39,40,41,42].

The present study, along with others, validates a significant association of high WHR and high WC with diabetes and hypertension, highlighting the validity of high WHR and high WC as a robust measure of risk for diabetes and hypertension [21, 43,44,45]. The likelihood of chronic respiratory disease was more among the elderly with abnormal BMI, i.e. underweight and obese. It may be because of chronic conditions like chronic bronchitis and asthma more prevalent in obese people [46, 47], whereas COPD is uncertain with abnormal BMI [46]. However, WC and WHR were positively related to COPD risk [48].

The BMI-obese, WC-high risk and WHR-high risk have a greater risk of having multi-morbidity compared with normal or low-risk persons [22, 49]. On the same line, in Lower and middle-income countries study, the likelihood of multi-morbidity was more than two times higher among India’s overweight and obese population [23]. The current study also revealed the same results. Further, anthropometric indices’ risk found insignificant predictors for cancer disease among the older adults after adjusted by various background and behavioural factors. It might cause the prevalence of cancer even less than 1 %. Certain studies discussing the relation between cancer risk and obesity are uncertain, as obesity’s risk depends on the cancer types [50, 51]. According to World Health Organization (WHO) Active Ageing Framework (2002), exercise and physical activity can play a significant role in reducing the global burden of NCDs [52]. We know that older person especially people aged more than 60 years, can’t be involved in extensive physical activity. However, even moderate levels of exercises such as walking, breathing exercises, etc., are also found to be effective in reducing the risk of NCDs. Hence, results from this study could be helpful for public health policymakers to formulate profound methods and strategies that will help promote physical activity among the elderly. Lifestyle affects anthropometric measures as well as influences the level of risk for NCDs. Therefore, the government can promote a healthy lifestyle and an awareness campaign from an early age at community levels for healthy ageing. Studies have suggested that such campaigns have a positive impact on people [53]. Some developed nations like the United States, Canada, Great Britain, and Australia have issued National Physical Activity Guidelines for older adults. In common, these guidelines recommend thirty minutes of moderate physical activities daily along with strength and balance training twice a week [54,55,56]. Canada has produced “Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines” for older adults aged 65 and above. It recommends Moderate to vigorous aerobic physical activities for at least 150 min a week and strength and balance exercises twice a week. Along with this, it also advises 7 to 8 h of good-quality sleep regularly, with consistent bed and wake-up times and limiting sedentary time to 8 h or less with no more than 3 h of screen time [54]. It is believed that following the twenty-four-hour movement guidelines is associated with normal physical health and benefits like a lower risk of mortality, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, several cancers. It also helps to reduce weight gain, anxiety, depression, dementia among the elderly [54].

A higher risk was found for people living in urban areas, and they are more prone to be overweight or obese because of the lifestyle or lack of exercise facilities such as parks, swimming pools, or walking roads in the neighbourhood [57]. Therefore, the planning of cities should be done keeping these facilities in mind. A healthy aged person can contribute to the economy and be helpful in many other ways for society. It was found that many factors indirectly affect the quality of healthy ageing by socioeconomic strata. Hence there is a need to focus on such aspects in social and health planning for the elderly. The health care professional can be trained to deal with elderly patients and educate them about NCDs various risk factors. They can suggest activities to do in their leisure time, increasing their activity and reducing the risk of NCDs [58]. It is also necessary to identify the gaps in existing health prompting policies and try to strengthen them.

Conclusion

Our study uses nationwide representative data from the first-ever population-based survey on ageing in India. It provides a comprehensive picture of physical indices, i.e., BMI, WC, and WHR, among older adults aged 45 and above in India. It also provides the prevalence of various NCDs and investigates the association of BMI, WC, and WHR with the NCDs. The study results made it evident that being in high-risk BMI, WC, and WHR increases NCDs’ risk and multi-morbidity among older adults. Thus, the policies on reducing the share of the elderly population in high-risk groups of BMIs, WHR, and WC should follow a multi-sectorial approach. A focus on specific subgroups of the elderly is required.

Limitations

There are some limitations to our study. Firstly, the NCDs’ prevalence may be under-reported as it is based on the individuals’ self-reporting as chronic disease stigma. Secondly, for adjusting our model by behavioural factors such as smoking and drinking, we have used the ever-smoked and ever-drink as the controlling variables, which might be not that much strong to indicate the intensity and duration of smoking and drinking, respectively. Third, the survey’s cross-sectional design does not infer the causal relationship between the physical body indices and the NCDs and also might be issues of individuals reverse causation and temporality. Lastly, in our data set, dietary patterns are not available, which have a greater impact on anthropometric measures. Also, we have not used South Asian criteria for anthropometric classification, which leads to underreporting of obese and overweight populations. Additionally, we have the aim to understand the overall older-aged scenario, but stratified analysis separately for male and female can add more insights in findings.

Availability of data and materials

The LASI Wave-1 data was collected by the nodal institution International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai on behalf of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. All data were de-identified. The de-identified version of the LASI Wave-1 data is publicly available to the researchers and policymakers upon formal request to the International Institute For Population Sciences for access (link to the data request document LASI_DataRequestForm_0.pdf (iipsindia.ac.in) and link for the other information for lasi data set LASI Wave-I | International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) (iipsindia.ac.in).

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- WHR:

-

Waist-to-hip Ratio

- WC:

-

Waist Circumference

- LASI:

-

Longitudinal Ageing Survey in India

- NCDs:

-

Non-communicable Diseases

- CVDs:

-

Cardio Vascular Diseases

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

References

United Nations, 2019. World Population Ageing. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Report.pdf [Accessed on March 6 2020].

Ministry of Statistics and programme implementation 2016. Retrieved from http://mospi.nic.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/ElderlyinIndia_2016.pdf [Accessed on March 8 2020].

Williams JS, Norström F, Ng N. Disability and ageing in China and India–decomposing the effects of gender and residence. Results from the WHO study on global ageing and adult health (SAGE). BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):1–13.

Petersen PE, Yamamoto T. Improving the oral health of older people: the approach of the WHO global Oral health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33(2):81–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00219.x.

Yadav S, Arokiasamy P. Understanding epidemiological transition in India. Glob Health Action. 2014;7(1):23248.

Kastor A, Mohanty SK. Disease-specific out-of-pocket and catastrophic health expenditure on hospitalisation in India: do Indian households face distress health financing? PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0196106.

Arokiasamy P, Kowal P, Capistrant BD, Gildner TE, Thiele E, Biritwum RB, et al. Chronic non-communicable diseases in 6 low-and middle-income countries: findings from wave 1 of the World Health Organization's study on global ageing and adult health (SAGE). Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185(6):414–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kww125.

Reddy KS, Shah B, Varghese C, Ramadoss A. Responding to the threat of chronic diseases in India. Lancet. 2005;366(9498):1744–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67343-6.

Jiang SZ, Lu W, Zong XF, Ruan HY, Liu Y. Obesity and hypertension. Exp Therapeutic Med. 2016;12(4):2395–2399.10. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2016.3667.

Donini LM, Chumlea WC, Vellas B, Del Balzo V, Cannella C. Preparation for the International Symposium on 'Obesity in the Elderly'; 2006.

World Health Organization, 2020. Obesity and overweight. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight , [Accessed on 5 March 2021].

World Health Organization, 2021.The Global health observatory. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/theme-details/GHO/body-mass-index-(bmi)?introPage=intro_3.html [Accessed on 5 March 2021].

Bloomgarden ZT. Third annual world congress on the insulin resistance syndrome: associated conditions. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(9):2165–74. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc06-zb09.

Strumpf E. The obesity epidemic in the United States: causes and extent, risks and solutions. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2004;713:1–6.

Hall DM, Cole TJ. What use is the BMI? Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(4):283–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2005.077339.

Larsson BKLLPG, Svärdsudd K, Welin L, Wilhelmsen L, Björntorp P, Tibblin GD. Abdominal adipose tissue distribution, obesity, and risk of cardiovascular disease and death: 13 year follow up of participants in the study of men born in 1913. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;288(6428):1401–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.288.6428.1401.

Lapidus L, Bengtsson C, Larsson BO, Pennert K, Rybo E, Sjöström L. Distribution of adipose tissue and risk of cardiovascular disease and death: a 12 year follow up of participants in the population study of women in Gothenburg, Sweden. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;289(6454):1257–61. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.289.6454.1257.

Han TS, Van Leer EM, Seidell JC, Lean MEJ. Waist circumference action levels in the identification of cardiovascular risk factors: prevalence study in a random sample. BMJ. 1995;311(7017):1401–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.7017.1401.

Lean MEJ, Han TS, Morrison CE. Waist circumference as a measure for indicating need for weight management. BMJ. 1995;311(6998):158–61. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.6998.158.

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), National Programme for Health Care of Elderly (NPHCE), MoHFW, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health (HSPH) and the University of Southern California (USC). In: Longitudinal ageing study in India (LASI) wave 1, 2017–18, India report. Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2020.

Olinto MTA, Nacul LC, Gigante DP, Costa JSD, Menezes AMB, Macedo S. Waist circumference as a determinant of hypertension and diabetes in Brazilian women: a population-based study. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7(5):629–35. https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2003582.

Zhang J, Xu L, Li J, Sun L, Qin W. Association between obesity-related anthropometric indices and multi-morbidity among older adults in Shandong, China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(5):e036664.

Agrawal S, Agrawal PK. Association between body mass index and prevalence of multi-morbidity in low-and middle-income countries: a cross-sectional study. Int J Med Public Health. 2016;6(2):73.

Arokiasamy P, Bloom DE, Lee J, O'Brien J, Parasuraman S. Biological markers and the health of older Indians: results from the 2010 LASI pilot. Econ Polit Wkly. 2016;51(1):47–58.

Status WP. The use and interpretation of anthropometry: report of a World Health Organization (WHO) expert committee. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1995.

Ahirwar R, Mondal PR. Prevalence of obesity in India: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2019;13(1):318–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2018.08.032.

Sowers JR. Obesity as a cardiovascular risk factor. Am J Med. 2003;115(8):37–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.08.012.

Dobbelsteyn CJ, Joffres MR, MacLean DR, Flowerdew G. A comparative evaluation of waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio and body mass index as indicators of cardiovascular risk factors. The Canadian heart health surveys. Int J Obes. 2001;25(5):652–61. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0801582.

World Health Organization, 2000. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic.

Larsson B. Obesity: a population study of men, with special reference to development and consequences for the health; 1978.

Garrison RJ, Feinleib M, Castelli WP, McNamara PM. Cigarette smoking as a confounder of the relationship between relative weight and long-term mortality: the Framingham heart study. JAMA. 1983;249(16):2199–203. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1983.03330400045023.

Wang M, Luo X, Xu S, Liu W, Ding F, Zhang X, et al. Trends in smoking prevalence and implication for chronic diseases in China: serial national cross-sectional surveys from 2003 to 2013. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(1):35–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30432-6.

Blair SN, Brodney S. Effects of physical inactivity and obesity on morbidity and mortality: current evidence and research issues. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(11 Suppl):S646–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-199911001-00025.

Sanya AO, Ogwumike OO, Ige AP, Ayanniyi OA. Relationship of waist-hip ratio and body mass index to blood pressure of individuals in Ibadan north local government. Afr J Physiother Rehabil Sci. 2009;1(1):7–11.

Zhang L, Zhang WH, Zhang L, Wang PY. Prevalence of overweight/obesity and its associations with hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome: a survey in the suburban area of Beijing, 2007. Obes Facts. 2011;4(4):284–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000331014.

Nicklas BJ, Cesari M, Penninx BW, Kritchevsky SB, Ding J, Newman A, et al. Abdominal obesity is an independent risk factor for chronic heart failure in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(3):413–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00624.x.

Decoda Study Group, Nyamdorj R. BMI compared with central obesity indicators in relation to diabetes and hypertension in Asians. Obesity. 2008;16(7):1622–35. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.73.

Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration. Body mass index and cardiovascular disease in the Asia-Pacific region: an overview of 33 cohorts involving 310 000 participants. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33(4):751–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyh163.

Tran NTT, Blizzard CL, Luong KN, Truong NLV, Tran BQ, Otahal P, et al. The importance of waist circumference and body mass index in cross-sectional relationships with risk of cardiovascular disease in Vietnam. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0198202.

Su TT, Amiri M, Mohd Hairi F, Thangiah N, Dahlui M, Majid HA. Body composition indices and predicted cardiovascular disease risk profile among urban dwellers in Malaysia. Biomed Res Int. 2015, 2015.

Dalton M, Cameron AJ, Zimmet PZ, Shaw JE, Jolley D, Dunstan DW, et al. Waist circumference, waist–hip ratio and body mass index and their correlation with cardiovascular disease risk factors in Australian adults. J Intern Med. 2003;254(6):555–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2003.01229.x.

Goh LG, Dhaliwal SS, Welborn TA, Lee AH, Della PR. Anthropometric measurements of general and central obesity and the prediction of cardiovascular disease risk in women: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2).

Chan JM, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Obesity, fat distribution, and weight gain as risk factors for clinical diabetes in men. Diabetes Care. 1994;17(9):961–9. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.17.9.961.

Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Canani LH, Karohl C, Chambless L. Association of waist-hip ratio with diabetes mellitus: strength and possible modifiers. Diabetes Care. 1992;15(7):912–4. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.15.7.912.

Grievink L, Alberts JF, O’niel J, Gerstenbluth I. Waist circumference as a measurement of obesity in the Netherlands Antilles; associations with hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58(8):1159–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601944.

Guerra S, Sherrill DL, Bobadilla A, Martinez FD, Barbee RA. The relation of body mass index to asthma, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema. Chest. 2002;122(4):1256–63. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.122.4.1256.

Poulain M, Doucet M, Major GC, Drapeau V, Sériès F, Boulet LP, et al. The effect of obesity on chronic respiratory diseases: pathophysiology and therapeutic strategies. Cmaj. 2006;174(9):1293–9. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.051299.

Li J, Zhu L, Wei Y, Lv J, Guo Y, Bian Z, et al. Association between adiposity measures and COPD risk in Chinese adults. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(4):1901899. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01899-2019.

Jovic D, Marinkovic J, Vukovic D. Association between body mass index and prevalence of multi-morbidity: a cross-sectional study. Public Health. 2016;139:103–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.05.014.

Ackerman SE, Blackburn OA, Marchildon F, Cohen P. Insights into the link between obesity and cancer. Curr Obes Rep. 2017;6(2):195–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-017-0263-x.

Kazan M, Karalti I. The association between obesity and Cancer. Endocrinol Metab Syndr. 2015;4:196.

Howe T, Skelton D. Physical activity and exercise for health and well being of older people; 2014.

Ayiesah R. The level of physical activities amongst elderly in a community. J Health Transl Med. 2007;10(1):29–33.

Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian physical activity guidelines: for older adults - 65 years & older; 2020. Available from: https://csepguidelines.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/24HMovementGuidelines-Adults-65-2020-ENG.pdf. Accessed June 11, 2021.

Sims J, Hill K, Hunt S, Haralambous B. Physical activity recommendations for older Australians. Australas J Ageing. 2010;29(2):81–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6612.2009.00388.x.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2018.

van den Bussche H, Schön G, Kolonko T, Hansen H, Wegscheider K, Glaeske G, et al. Patterns of ambulatory medical care utilisation in elderly patients with special reference to chronic diseases and multimorbidity-results from a claims data based observational study in Germany. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-11-54.

Mensink GB, Ziese T, Kok FJ. Benefits of leisure-time physical activity on the cardiovascular risk profile at older age. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28(4):659–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/28.4.659.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the LASI-survey, which was done by nodal agency International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai, for providing the relevant data for this study.

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the manuscript. MB and MP: Study design, carried out the statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. GS and NM handle the data and interpretation and helps to draft the manuscript. BR and AS have the main role in drafting the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable, this is a secondary based survey. For this study no patient could be identified or contacted, no ethics approval was required by individual researchers to undertake this study. The LASI Data collected under the approved ethical consideration of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) guidelines. (Please refer to the document National ethical guidelines for biomedical and health research involving human participants link to the document-ICMR_Ethical_Guidelines_2017.pdf).

Consent for publication

Not applicable for this study.

Competing interests

All authors have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bramhankar, M., Pandey, M., Rana, G.S. et al. An assessment of anthropometric indices and its association with NCDs among the older adults of India: evidence from LASI Wave-1. BMC Public Health 21, 1357 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11421-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11421-4