Abstract

Background

Many efforts are being made around the world to discover the vaccine against COVID-19. After discovering the vaccine, its acceptance by individuals is a fundamental issue for disease control. This study aimed to examine COVID-19 vaccination intention determinants based on the protection motivation theory (PMT).

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study in the Iranian adult population and surveyed 256 study participants from the first to the 30th of June 2020 with a web-based self-administered questionnaire. We used Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to investigate the interrelationship between COVID-19 vaccination intention and perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived self-efficacy, and perceived response efficacy.

Results

SEM showed that perceived severity to COVID-19 (β = .17, p < .001), perceived self-efficacy about receiving the COVID-19 vaccine (β = .26, p < .001), and the perceived response efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccine (β = .70, p < .001) were significant predictors of vaccination intention. PMT accounted for 61.5% of the variance in intention to COVID-19 vaccination, and perceived response efficacy was the strongest predictor of COVID-19 vaccination intention.

Conclusions

This study found the PMT constructs are useful in predicting COVID-19 vaccination intention. Programs designed to increase the vaccination rate after discovering the COVID-19 vaccine can include interventions on the severity of the COVID-19, the self-efficacy of individuals receiving the vaccine, and the effectiveness of the vaccine in preventing infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Vaccines are one of the cost-effective measures of prevention [1]. Immunization against infectious diseases annually prevents millions of deaths by affecting the immune system [2]. The spread of COVID-19 as an emerging disease in the world requires immediate action, including the production of vaccines, which can be an effective measure to protect people against this disease [3]. Many efforts are being to prevent individuals from getting COVID-19 through vaccination [4]. After providing the vaccine, the critical issue is its acceptance by the individuals. A survey of American adults found that about a third of them will accept COVID-19 vaccination [5]. Also, A report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that less than half of American adults vaccinated against the flu in the 2018–2019 season [6].

Evidence shows that the rate of influenza vaccination is low in Asian populations [7], and this rate in Iran is much lower than expected by the World Health Organization [8]; however, Iran is one of the countries that announced the highest agreement on the importance of the vaccine [9]. The evidence shows that misconceptions are among the main reasons for not getting the flu vaccine [10].

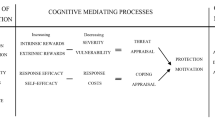

According to a global report in 2017, most countries report that people are hesitant about vaccination [11]. Factors affecting COVID-19 vaccination acceptance may be as important as the discovery of the vaccine [12]. It is unclear how effective the pandemic status is in accepting the COVID-19 vaccine, and doubts about the vaccine acceptance remain [13]. Policymakers can identify factors related to vaccine acceptance to guide effective interventions to increase vaccination acceptance in the population [14]. The theory of protection motivation (PMT) is one of the most recognized expectancy-value theories that explain the effects of fear appeals on attitude change [15]. Behavioral change interventions widely use fear appeal to be effective. Fear appeals when messages contain a description of perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, and expressions of response efficacy can positively affect individuals’ knowledge, attitude, and performance, especially in onetime behaviors (e.g., Covid-19 vaccination) [16, 17].

A recent study examining the effectiveness of the PMT in predicting seasonal influenza vaccination intent has shown that this model is a good predictor [18]. Also, a survey that used protective motivation theory to predict COVID-19 preventive behaviors in Iran showed that the response efficacy and self-efficacy predicted COVID-19 protective behaviors [19]. Furthermore, evidence shows that threat and coping appraisal in hospital staff were predictors of protection motivation during the COVID-19 pandemic [20]. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have so far examined the predictors of intention to vaccinate COVID-19 using the PMT. This study aimed to investigate the predictors of COVID-19 vaccination intention using the PMT in the Iranian population.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional study in the Iranian adult population 18 years and older and surveyed 265 participants from the first to the 30th of June 2020 with a web-based self-administered questionnaire. We made a questionnaire based on the conceptual framework of the PMT on the Porsline, an online survey platform in Iran (https://survey.porsline.ir). We recruited participants with the self-selection sampling method and posted the online survey link on Telegram and WhatsApp, two of Iran’s most widely used social media platforms. The questionnaire began with an information letter about the study’s purpose, how to answer questions, and informed consent to participate in the study.

We asked participants about their demographic characteristics, including age, gender, education, and marital status. Also, we asked the participants about the perceived severity of COVID-19, perceived susceptibility to COVID-19, perceived self-efficacy in performing the COVID-19 vaccination and perceived response efficacy of COVID-19 vaccine, and intention to be vaccinated against COVID-19 whenever the vaccine was available. All answers were on 5-point Likert scales. We conducted this study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the ethics committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences approved this study’s protocol (IR.ZAUMS.REC.1399.015).

Data analysis

The analytical procedure consisted of two major tests: first, we performed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). CFA examines the relationships between observed measures or indicators and latent variables or factors [21]. We checked the overall sample for the goodness of fit of the hypothetical measurement model of each domain, postulated by protection motivation theory developers. We performed structural equation modeling (SEM) to test for the proposed model in the next step. For investigating the fit of each model, we calculated the chi-square (χ2) statistic. However, this well-known statistic is not a useful model fit index practically because of the detection of even trivial differences under a large sample size [22]. Therefore, for more reliable results besides this test, we considered other goodness of fit indices like Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) for a final decision about accepting or rejecting the hypothesis. A value of CFI ≥ 0.90, TLI ≥ 0.90, and RMSEA≤0.08 can support a good model fit [23]. We chose full information maximum likelihood estimation as estimators. CFA and SEM run by Mplus 8.3 [24].

Results

Participant characteristics

The average age of participants was 37.73 ± 12.27 years; 46.2% of them were male. 83.7% of participants had a university degree, 47.3% had an undergraduate degree, and 36.4% had a graduate degree. The survey responses in graphical form stratified by intent to get a vaccine are presented in Fig. 1.

We reported the descriptive statistics of measured variables in the model in Table 1, including skewness and kurtosis, which are indicators for univariate normality. The mean score range of items ranges from 3.208 to 4.475, and standard deviation scores range from 0.723 to 1.164. All items’ skewness and kurtosis scores fall in the acceptable ranges of normality suggested by Kline (skewness does not exceed |3| and kurtosis does not exceed |10|) [25].

We reported the Cronbach’s alphas, the composite reliability (CR), and the average variance extracted (AVE) in Table 2. All Cronbach’s alphas, CR and AVE, were greater than 0.70, indicating good reliability and validity of items within a construct (Table 2).

CR for perceived severity and perceived response efficacy were 0.92 and 0.861, respectively, which were above the threshold of 0.7 AVE. Perceived severity and perceived response efficacy were 0.696 and 0.756, respectively, which were above 0.5. The discriminant validity results based on the Fornell-Larcker criterion are shown in Table 3.

Predictors of COVID-19 vaccination intention

As mentioned earlier, the first step in testing SEM is to check whether the overall sample data fit the measurement model or not. The CFA analysis for all domains showed approximately acceptable CFI, TLI, and RMSEA values. Perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived self-efficacy, and perceived response efficacy were predictors of intention in model 1. As shown in Table 4, the goodness of fit incidence of the model was χ2= 655.911, P-value< 0.001, CFI = 0.960, TLI = 0.950, and RMSEA =0.081. Although all goodness of fit indices were acceptable, perceived susceptibility was not significant, so we omitted perceived susceptibility to find a better model. Figure 2 also shows the graphical description of SEM analysis results. In Table 5, you can see all coefficients for the measurement model and path analysis.

In model 2, perceived severity, perceived self-efficacy, and perceived response efficacy were predictors of intention. As shown in Table 4, the goodness of fit incidence of the model was χ2= 109.164, P-value< 0.001, CFI = 0.952, TLI = 0.933, and RMSEA =0.096. In this model, all goodness of fit indices are acceptable, and this model can explain 61.5% of the variance of intention. Figure 3 also shows the graphical description of the results of the SEM analysis. In Table 6, you can see all coefficients for the measurement model and path analysis. As shown in this Table, perceived severity to COVID-19 (β = .12, p < .001), perceived self-efficacy about receiving the COVID-19 vaccine (β = .26, p < .001), and the perceived response efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccine (β = .52, p < .001) were significant predictors of vaccination intention. Response efficacy was the strongest predictor of COVID-19 vaccination intention.

Discussion

Identification of factors influencing the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine should begin before a vaccine becomes available. The current study applies the PMT to identify predictors of COVID-19 vaccination intention in the Iranian adult population. We used SEM to investigate the interrelationship between COVID-19 vaccination intention and perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived self-efficacy, and perceived response efficacy. The results showed that if the COVID-19 vaccine is available, the PMT could be a good predictor for vaccination intention. Previous studies that have used the PMT to predict vaccination intention have shown its effectiveness [26, 27]. A study that examined the predictor of seasonal influenza vaccination intention based on the PMT showed that the PMT accounted for 62% of vaccination intention variance [18].

The current study showed that perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 was not a significant predictor of vaccination intention. Participants in this study scored less than 70% of the maximum score of perceived susceptibility score, and this finding indicates that participants did not consider themselves very susceptible to COVID-19. In studies examining the intention to vaccinate against H1N1 influenza, perceived susceptibility to influenza H1N1 virus did not predict vaccination intention [28, 29]. Therefore, interventions should be designed and implemented by the health system to sensitize people to COVID-19. SEM showed that perceived severity to COVID-19, perceived self-efficacy about receiving the COVID-19 vaccine, and the perceived efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccine were significant predictors of vaccination intention. The three-factor model accounted for 61.5% of the total variance.

There is evidence that higher consideration of vaccination future consequences is associated with the perceived severity of the disease, greater perceived self-efficacy, and higher perceived effectiveness of the vaccine [30, 31]. An extensive survey that examined the willingness to vaccinate against seven vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States showed that different degrees of risk are associated with the number of people willing to be vaccinated [32].

Additionally, a study examining the acceptability of the COVID-19 vaccine found that participants who reported higher levels of perceived severity of COVID-19 infection and perceived effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccine were more likely to be willing to get vaccinated [5]. This study indicates that the perceived response efficacy is the strongest predictor of COVID-19 vaccination intention among the PMT construct. Regarding the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine, other studies revealed that belief in vaccine efficacy was significantly the probability of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance [33, 34].

However, there is evidence that other factors can play a decisive role in influenza vaccination, despite understanding its effectiveness [35]. The previous research shows that perceived self-efficacy is one of the most critical factors in adherence to COVID-19 preventive measures [36]. Perceived self-efficacy refers to a sense of control over novel or difficult situations and challenges through decent behavior [37]. In behaviors such as vaccination that do not involve long-term treatment adherence, self-efficacy is a determinant of intention and behavior [38].

In a previous study that used PMT to predict staying at home during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Japanese population, self-efficacy was a predictor. Like this study’s results, perceived severity leads to threat appraisal more than perceived vulnerability, and perceived self-efficacy and perceived response efficiency leads to coping appraisal [39]. Also, evidence showed that perceived severity and self-efficacy were significantly related to the self-isolation intention during the COVID-19 pandemic [40].

Therefore, to encourage people to get vaccinated against COVID-19, more emphasis should be placed on perceived severity and perceived response efficiency. Because vaccination intention and actual vaccination uptake are related [41], identifying factors influencing vaccination intention before the availability of the COVID-19 vaccine can pave the way for community acceptance of the vaccine. Therefore, future intervention to increase COVID-19 vaccine acceptance can consider the PMT as a conceptual framework.

Readers should interpret our findings in light of the following study limitations. First, the COVID-19 vaccine is not yet available, and individuals’ answers to questions about vaccine efficacy and self-efficacy related to the vaccine may differ when the vaccine is available. Also, the distribution and cost of the vaccine are not known. If a vaccine provides in the future, the people who have access to the vaccine may have different characteristics from the participants in this study. Second, because we selected participants to study through an online survey platform, the findings may be prone to selection bias. Third, this study’s data were self-reported, and participants’ responses may prone to social desirability bias.

Conclusions

The current study identified factors associated with the COVID-19 vaccination intention. Understanding the factors influencing vaccination can help health policymakers increase vaccine acceptance. Programs designed to increase the vaccination rate after the availability of the COVID-19 vaccine can include interventions on the severity of the COVID-19, the self-efficacy of individuals receiving the vaccine, and the effectiveness of the vaccine in preventing infection.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PMT:

-

Protection Motivation Theory

- SEM:

-

Structural Equation Modeling

- CFA:

-

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

- CFI:

-

Comparative Fit Index

- TLI:

-

Tucker-Lewis Index

- RMSEA:

-

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation.

- CR:

-

Composite Reliability (CR)

- AVE:

-

Average Variance Extracted

References

Orenstein WA, Ahmed R. Simply put: vaccination saves lives. National Acad Sciences; 2017.

Organization WH. Assessment report of the global vaccine action plan. Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization. Geneva: WHO; 2017.

Yang P, Wang X. COVID-19: a new challenge for human beings. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17(5):555–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41423-020-0407-x.

Organization WH. DRAFT landscape of COVID-19 candidate vaccines. World. 2020.

Reiter PL, Pennell ML, Katz ML. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: how many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine. 2020;38(42):6500–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.043.

Control CfD, Prevention. Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2018–19 influenza season. 2019.

Sheldenkar A, Lim F, Yung CF, Lwin MO. Acceptance and uptake of influenza vaccines in Asia: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2019;37(35):4896–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.07.011.

Tanjani PT, Babanejad M, Najafi F. Influenza vaccination uptake and its socioeconomic determinants in the older adult Iranian population: a national study. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(5):e1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2015.02.001.

Larson HJ, De Figueiredo A, Xiahong Z, Schulz WS, Verger P, Johnston IG, et al. The state of vaccine confidence 2016: global insights through a 67-country survey. EBioMedicine. 2016;12:295–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.08.042.

Zaraket H, Melhem N, Malik M, Khan WM, Dbaibo G, Abubakar A. Review of seasonal influenza vaccination in the eastern Mediterranean region: policies, use and barriers. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(3):377–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2020.02.029.

Lane S, MacDonald NE, Marti M, Dumolard L. Vaccine hesitancy around the globe: analysis of three years of WHO/UNICEF joint reporting form data-2015–2017. Vaccine. 2018;36(26):3861–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.03.063.

Neumann-Böhme S, Varghese NE, Sabat I, Barros PP, Brouwer W, van Exel J, et al. Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Springer; 2020.

Dubé E, MacDonald NE. How can a global pandemic affect vaccine hesitancy?: Taylor & Francis; 2020.

Betsch C, Böhm R, Chapman GB. Using behavioral insights to increase vaccination policy effectiveness. Policy Insights Behav Brain Sci. 2015;2(1):61–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732215600716.

Rogers RW. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change1. Aust J Psychol. 1975;91(1):93–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1975.9915803.

Tannenbaum MB, Hepler J, Zimmerman RS, Saul L, Jacobs S, Wilson K, et al. Appealing to fear: a meta-analysis of fear appeal effectiveness and theories. Psychol Bull. 2015;141(6):1178–204. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039729.

Ruiter RA, Kessels LT, Peters GJY, Kok G. Sixty years of fear appeal research: current state of the evidence. Int J Psychol. 2014;49(2):63–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12042.

Ling M, Kothe EJ, Mullan BA. Predicting intention to receive a seasonal influenza vaccination using protection motivation theory. Soc Sci Med. 2019;233:87–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.06.002.

Rad RE, Mohseni S, Takhti HK, Azad MH, Shahabi N, Aghamolaei T, et al. Application of the protection motivation theory for predicting COVID-19 preventive behaviors in Hormozgan, Iran: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–11.

Bashirian S, Jenabi E, Khazaei S, Barati M, Karimi-Shahanjarini A, Zareian S, et al. Factors associated with preventive behaviours of COVID-19 among hospital staff in Iran in 2020: an application of the protection motivation theory. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105(3):430–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2020.04.035.

Brown TA, Moore MT. Confirmatory factor analysis. Handbook of structural equation modeling; 2012. p. 361–79.

Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J. 2002;9(2):233–55. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5.

Hu L-t, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Muthén LK, Muthen B. Mplus user's guide: statistical analysis with latent variables, user’s guide: Muthén & Muthén; 2017.

Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling: Guilford publications; 2015.

Camerini A-L, Diviani N, Fadda M, Schulz PJ. Using protection motivation theory to predict intention to adhere to official MMR vaccination recommendations in Switzerland. SSM-Population Health. 2019;7:100321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.11.005.

Liu C, Nicholas S, Wang J. The association between protection motivation and hepatitis b vaccination intention among migrant workers in Tianjin, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–10.

Lau JT, Yeung NC, Choi K, Cheng MY, Tsui H, Griffiths S. Factors in association with acceptability of a/H1N1 vaccination during the influenza a/H1N1 pandemic phase in the Hong Kong general population. Vaccine. 2010;28(29):4632–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.04.076.

Coe AB, Gatewood SB, Moczygemba LR. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the novel (2009) H1N1 influenza vaccine. Innovations Pharm. 2012;3(2):1–11. https://doi.org/10.24926/iip.v3i2.257.

Kim J, Kim Y. Consideration of future consequences and predictability: examining six health behaviors with different levels of perceived severity. Soc Sci J. 2020;1:1–9.

Nan X, Kim J. Predicting H1N1 vaccine uptake and H1N1-related health beliefs: the role of individual difference in consideration of future consequences. J Health Commun. 2014;19(3):376–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2013.821552.

Baumgaertner B, Ridenhour BJ, Justwan F, Carlisle JE, Miller CR. Risk of disease and willingness to vaccinate in the United States: a population-based survey. PLoS Med. 2020;17(10):e1003354. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003354.

Pogue K, Jensen JL, Stancil CK, Ferguson DG, Hughes SJ, Mello EJ, et al. Influences on attitudes regarding potential COVID-19 vaccination in the United States. Vaccines. 2020;8(4):582. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines8040582.

Wang J, Jing R, Lai X, Zhang H, Lyu Y, Knoll MD, et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Vaccines. 2020;8(3):482. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines8030482.

Lutz CS, Fink RV, Cloud AJ, Stevenson J, Kim D, Fiebelkorn AP. Factors associated with perceptions of influenza vaccine safety and effectiveness among adults, United States, 2017–2018. Vaccine. 2020;38(6):1393–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.12.004.

Chong YY, Chien WT, Cheng HY, Chow KM, Kassianos AP, Karekla M, et al. The role of illness perceptions, coping, and self-efficacy on adherence to precautionary measures for COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6540. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186540.

Warner LM, Schwarzer R. Self-efficacy and health. Wiley Encyclopedia Health Psychol. 2020;1:605–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119057840.ch111.

Fall E, Izaute M, Chakroun-Baggioni N. How can the health belief model and self-determination theory predict both influenza vaccination and vaccination intention? A longitudinal study among university students. Psychol Health. 2018;33(6):746–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2017.1401623.

Okuhara T, Okada H, Kiuchi T. Predictors of staying at home during the COVID-19 pandemic and social lockdown based on protection motivation theory: a cross-sectional study in Japan. InHealthcare 2020;8(4):475. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040475.

Farooq A, Laato S, Islam AN. Impact of online information on self-isolation intention during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(5):e19128. https://doi.org/10.2196/19128.

Gargano LM, Painter JE, Sales JM, Morfaw C, Jones LM, Murray D, et al. Seasonal and 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccine uptake, predictors of vaccination, and self-reported barriers to vaccination among secondary school teachers and staff. Hum Vaccines. 2011;7(1):89–95. https://doi.org/10.4161/hv.7.1.13460.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants in this study.

Funding

The Zahedan University of Medical Sciences supported the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HOA and MS participated in designing the study; ZS and MM participated in data analysis; HOA and AAM interpreted the results and prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences approved this study’s protocol (IR.ZAUMS.REC.1399.015). Participants expressed informed consent to participate in the study before beginning to respond to the online questionnaire.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ansari-Moghaddam, A., Seraji, M., Sharafi, Z. et al. The protection motivation theory for predict intention of COVID-19 vaccination in Iran: a structural equation modeling approach. BMC Public Health 21, 1165 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11134-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11134-8