Abstract

Introduction

Zambia is among the countries with the highest HIV burden and where youth remain disproportionally affected. Access to HIV testing and counselling (HTC) is a crucial step to ensure the reduction of HIV transmission. This study examines the changes that occurred between 2007 and 2018 in access to HTC, inequities in testing uptake, and determinants of HTC uptake among youth.

Methods

We carried out repeated cross-sectional analyses using three Zambian Demographic and Health Surveys (2007, 2013–14, and 2018). We calculated the percentage of women and men ages 15–24 years old who were tested for HIV in the last 12 months. We analysed inequity in HTC coverage using indicators of absolute inequality. We performed bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses to identify predictors of HTC uptake in the last 12 months.

Results

HIV testing uptake increased between 2007 and 2018, from 45 to 92% among pregnant women, 10 to 58% among non-pregnant women, and from 10 to 49% among men. By 2018 roughly 60% of youth tested in the past 12 months used a government health centre. Mobile clinics were the second most common source reaching up to 32% among adolescent boys by 2018. Multivariate analysis conducted among men and non-pregnant women showed higher odds of testing among 20–24 year-olds than adolescents (aOR = 1.55 [95%CI:1.30–1.84], among men; and aOR = 1.74 [1.40–2.15] among women). Among men, being circumcised (aOR = 1.57 [1.32–1.88]) and in a union (aOR = 2.44 [1.83–3.25]) were associated with increased odds of testing. For women greater odds of testing were associated with higher levels of education (aOR = 6.97 [2.82–17.19]). Education-based inequity was considerably widened among women than men by 2018.

Conclusion

HTC uptake among Zambian youth improved considerably by 2018 and reached 65 and 49% tested in the last 12 months for women and men, respectively. However, achieving the goal of 95% envisioned by 2020 will require sustaining the success gained through government health centres, and scaling up the community-led approaches that have proven acceptable and effective in reaching young men and adolescent girls who are less easy to reach through the government facilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

HIV/AIDS remains a leading cause of death in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), with around 663,000 deaths estimated in 2019 [1, 2]. In the sub-Sahara African region, home to more than two-thirds (25.7 million) of people living with HIV globally, HIV/AIDS is the fourth leading cause of death [2]. The remarkable scale-up of access to HIV prevention and care services made in the past two decades, through multiple global health initiatives such as the Global Fund to Fight Tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, and Malaria (GFATM), and the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) [3], has led to a significant reduction in morbidity and mortality due to HIV/AIDS in affected populations [2]. Despite the overall progress, only minor declines in new HIV infections have been observed among young people in high-burden countries, especially for adolescent girls and young women [4, 5]. Youth (15–24 years) still account for over 30% of new HIV infections each year globally [6].

Zambia faces a generalised HIV epidemic with an estimated prevalence of 11% among adults (15–49 years), which ranks it among the ten most affected countries globally [7, 8]. Among 48,000 estimated new infections in 2018, 39% were youth; of which more than two-thirds were women [9]. National data show that around 90% of these HIV infections are the result of unprotected heterosexual intercourse [10]. Individual and contextual drivers are thought to be among the main contributors of transmission including biological, behavioural, cultural, socio-economic, and legal factors [10,11,12,13,14]. HIV prevention programs that comprehensively address these drivers are required to achieve substantial change in the incidence of infection, with a cascade HIV care approach being key to the reduction of HIV transmission [15, 16].

In 2014, UNAIDS launched a fast-track global strategy to end the HIV epidemic by 2030, central to which is the 90–90-90 cascade goals; namely, aiming to ensure that 90% of people living with HIV know their status, 90% of those in HIV care are initiated on antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 90% of those on ART achieve viral load suppression by 2020 [17]. HIV testing and counselling (HTC) services are therefore critical for the reduction of new infections because they constitute the entry point of this cascade of HIV care and the means through which the first step of the 90–90-90 UNAIDS goal can be achieved [18,19,20]. Unfortunately, the use of HTC services has generally been reported to be low among youth in Zambia, and several barriers to accessing these services have been highlighted [21,22,23,24]. In alignment with the UNAIDS fast-track strategy, the Zambian government launched the HTC Implementation Plan (2014–16), which aimed to achieve by 2015 50% HTC coverage among adults for testing and receipt of the results in the last 12 months, to guarantee that the country remains on track with the 2020 targets [25]. The ongoing current National AIDS Strategic Framework (NASF) 2017–2021 remained aligned with the UNAIDS 90–90-90 global strategy and integrated the priority given to adolescents and young people [10]; such that the related HTC guidelines recommended for adolescents (10–19 years) and adults who are sexually active or with unknown HIV status to undertake a serological HIV test at first contact with health services, 3 months later if they were negative for the first test, and repeat the test every 6 months [26, 27].

To our knowledge, no study has investigated changes in HTC uptake among youth in Zambia after the launch of the 90–90-90 fast track targets and youth-specific global initiatives (“ALL IN Initiative” and “THREE fast-track”), which were launched to boost the HIV response toward this population [28, 29]. Moreover, the uncertainty around achieving the 2020 goals for HIV/AIDS-related morbidity and mortality among youth reflects the challenges in accessing HIV prevention and treatment services and highlights the importance of understanding who is, and who is not accessing the first step of the cascade of HIV care - HTC - and associated factors, to help refine control strategies and maximise the impact of future interventions [6].

The objectives of this study were to examine changes in uptake of HTC among youth between 2007 and 2018, to explore inequity in testing uptake over time, and to identify the determinants of HTC among young women and men ages 15–24 years-old in Zambia.

Methods

Data source and study population

This study used three datasets from the 2007, 2013–14, and 2018 Zambian Demographic Health Surveys (DHS). The Zambia Statistics Agency conducts these nationally representative, population-based surveys using a stratified two-stage cluster sampling method [7, 24]. In this study, we included all women and men respondents ages 15–24 years old, regardless of reported sexual activity.

Outcome variable

The primary outcome of interest was respondents reporting that they had been tested for HIV in the last 12 months and received the results.

Determinants of HIV testing

Potential determinants of HIV testing and counselling were selected based on Andersen’s behavioural model which suggests three factors influencing utilisation of a health service [30, 31]; specifically, (i) predisposing factors in any condition that can enhance the risk of engaging in unprotected sexual behavior, such as age and education; (ii) enabling factors that would increase chances of greater access to HTC, such as wealth and urban residence; and (iii) required factors which would affect a perceived need for HTC, such as knowledge of HIV or being sexually active. On this basis, we identified available determinants in the DHS, shown in Fig. 1 (a full list and definitions are shown in Supplementary Table S1) [21, 32,33,34,35,36].

Data analysis

For each survey we calculated the percentage of respondents tested for HIV in the last 12 months who received results; for adolescents (15–19), and young (20–24) women and men separately. To examine the extent of an antenatal care (ANC) session as a contributing factor in higher testing rates among women, we separated them into non-pregnant and pregnant groups. The testing uptake for pregnant women considered those who had a birth in the last 12 months and received their test as part of ANC. The source of HTC (in the last 12 months) was also described for each survey and each age group of women and men, separately. The numbers of annual tests conducted through each testing source were estimated by multiplying the percentage of tests reported per source multiplied by the estimated population of young women and men obtained from the World Bank population projections [37]; separately for adolescents and young adults of each gender.

We examined changes in inequity in HIV testing coverage from 2007 to 2018 separately among men and non-pregnant women. We used the Equiplot graph suggested by the International Center for Equity in Health (ICEH) to illustrate changes across time points for inequalities related to age, residence, education level, and household wealth [32, 38]. The mean coverage difference from the best-performing region was also calculated to show regional disparities in testing coverage across time points [39]. We restricted the analysis of inequity and predictors of HTC uptake among women to those non-pregnant, to avoid bias in the estimate of HIV testing coverage due to high rates observed through ANC.

Potential determinants (listed in Fig. 1) of HTC uptake were examined using the most recent survey dataset (2018). We first described respondent characteristics, then conducted bivariate analyses to identify those associated with the primary outcome; specifically, HIV testing in the last 12 months with receipt of results. After checking for collinearity and excluding variables with missing values for the outcome, all variables associated with the primary outcome (with p < 0.05) were considered for inclusion in the multivariate logistic regression models. The main models were run separately for men and non-pregnant women. Considering that 90% of HIV infections are reported to be transmitted through heterosexual intercourse in Zambia [10], a sub-group analysis restricted to men and non-pregnant women reported being sexually active was also conducted to identify specific determinants associated with HTC uptake in this population.

STATA SE version 16.1 (Stata Corporation, Ltd. Texas, USA) was used for analysis, and all analyses considered clustering, weighting, and stratification using the svyset command.

Results

Changes in HIV testing uptake

Overall, an improvement in HIV testing was observed between 2007 and 2018, with the percentage tested and receiving the results in the last 12 months increasing from 17 to 65% among young women, and from 10 to 49% among young men (Fig. 2a). These increases, observed in both genders and age groups (ages 15–19 and 20–24), were more pronounced between the period 2007–2013 than 2013–2018, and the absolute increase was higher among women than men (Fig. 2b). The testing rate among pregnant women, tested as part of ANC, increased considerably from 2007 to 2013 and nearly reached universal coverage for both age groups, with almost no change between 2013 and 2018. Figure 2b also shows that HIV testing uptake among non-pregnant women was much lower in all age groups than among women who received a test as part of ANC. Moreover, women not recently pregnant had almost the same testing coverage as men between 2007 and 2013, for both age groups. Nevertheless, a small difference between genders was noted from 2013 to 2018 within each age group, and more pronounced among young adults.

Source of HIV test

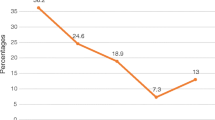

Figure 3a shows the proportions of HIV tests received through each testing source between 2007 and 2018. Government health centres (GHC) accounted for more than half of HIV tests for adolescent girls and young women in 2007, and their proportion increased over time, with more than 60% in each age group getting tested at a GHC in 2018. GHCs accounted for a much smaller percentage among men in 2007 but increased considerably in 2013, and by 2018 became the source for more than 50% of HIV tests among men. Moreover, the percentage getting tested in mobile clinics (MC) almost doubled in all four groups between 2013 and 2018, reaching 32% among adolescent boys. The increase in the percentage of youth tested in either GHCs or MCs masks considerable increases in the absolute number of tests performed through these sources, due to the overall increase in the percentage of youth, as shown in Fig. 3b. For GHCs the estimated number of tests performed for youth increased substantially from roughly 163,000 in 2007 to 1.3 million in 2018. For MC sources, the overall estimated number of tests reached approximately 400,000 in 2018 compared to 41,000 in 2007.

Determinants of HIV testing uptake in the 2018 DHS

Characteristics of the target population in the 2018 DHS dataset are shown in Table 1.

In the multivariate models, the ages 20–24 were commonly associated with high odds of HIV testing among both non-pregnant women (adjusted odds ratio = 1.74, 95%CI:1.40–2.15) and men (aOR = 1.55, 95%CI:1.30–1.84) (Tables 2 and 3). Among women the odds of testing increased with the level of education attained (aOR = 6.97; 95%CI:2.82–17.19, for higher education compared to no education). Among men high HIV testing uptake was mainly predicted by being circumcised (aOR = 1.57; 95%CI:1.32–1.88) and currently being in a union (aOR = 2.46, 95%CI:1.85–3.28, compared to never in union).

Among men and non-pregnant women who reported previous sexual experience, condom use at last intercourse was not associated with HIV testing uptake among women but was a predictor of testing among men (aOR = 1.64, 95%CI: 1.32–2.04) (Tables S2 and S3 in SM). Other predictors of testing were like the main models, except for not reporting HIV-related stigma manifestation which was associated with higher odds of testing among non-pregnant sexually active women (aOR = 1.59, 95%CI:1.14–2.21, compared to those reporting about stigma) (Tables S2); while having a discriminatory attitude was no longer a predictor for among men.

Inequity in HIV testing uptake

We analysed inequities in HIV testing uptake for a test taken and results received in the last 12 months for age, residence, education level, household wealth, and regions at each time point among men and young non-pregnant women. The results suggested an overall improvement in testing coverage between 2007 and 2018 in each sub-group for all inequality qualifiers (Fig. 4). However, by 2018 the absolute inequity in coverage widened between sub-groups for both genders. Less well covered were those age 15–19 years-old, living in rural areas, less educated, and the poorest (Figs. 4a-d). Education-based inequity was more considerable by 2018 among women (54% absolute difference between no education and higher education) than men (31%) (Fig. 4c). Regarding regions, by 2018 the disparities in testing coverage across regions increased among women (increase in the mean difference from the best-covered region from 4% in 2007 to 17% in 2018) (Fig. 5). Among men, however, an opposite trend was observed between 2007 and 2018; specifically, a reduction in the mean difference from the best-covered region from 21% in 2007 to 9% in 2018.

Discussion

This study analyses in-depth the uptake of HTC services among youth in Zambia, using nationally representative population-based survey data. We demonstrate an increase in uptake of HTC between 2007 and 2018, from 45 to 92% among pregnant women, 10 to 58% among non-pregnant women, and from 10 to 49% among men. Government health centres became the primary source of HIV testing by 2018, performing around 60% of all tests among youth. The percentage of tests delivered through mobile clinics almost doubled in all groups between 2013 and 2018 and accounted for one-third of all tests among adolescent boys. Multivariate analysis conducted for men and non-pregnant women showed higher odds of testing among young adults than adolescents (aOR = 1.55 among men and aOR = 1.74 among women). Circumcision and in a union were associated with higher odds of testing among men, whereas higher education and not reporting HIV-related stigma were predictors of testing among non-pregnant sexually active women. Inequity analyses mainly found an improvement in testing coverage in each sub-group of all inequality qualifiers by 2018, although the absolute difference in coverage was widened between the sub-groups for both genders. Education-based inequity was substantially increased among women than men by 2018.

The trend observed in this study for HTC uptake among youth demonstrates a considerable improvement over time in Zambia. Among pregnant women, the achievement could be related to the integration into ANC services since 2005 of a program of prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT), intensively promoted among pregnant women to ensure almost universal access to HTC around 2013 [40, 41]. The great level of attendance to ANC services among pregnant Zambian women was reported by the 2007 DHS (97% of women with at least one ANC visit) and maintained in 2013–14 and 2018 (roughly 98% for both reports); and was likely a contributing factor for inclusion of young women regardless of their age [7, 24, 42].

Regarding men, the promotion of couple HIV counselling and testing (CHCT) among partners of women attending ANC might be a factor to consider, especially considering that multivariate analysis in our study showed a high odds of testing among men in a union [43,44,45]. In our results the voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) as part of the main predictors of HIV testing among young men suggests a potential contribution of the VMMC campaigns launched in 2012 in Zambia. These campaigns reached over 400,000 men by 2013, and included HIV testing and other preventive services in addition to circumcision [46, 47]. Its scale-up in 2016, mainly through the mobile clinics, might explain the increase in the proportion of this source of delivery as reflected in our results for adolescent boys in 2018 (32% of testing through MC). The increasing proportion of HIV tests offered through MC observed in the study reflects an attempt of the Zambian government to reach underserved and hard-to-reach youth. In addition to the latter, other community-based strategies that are specific to youth should be explored given their promising results, such as adolescent-focused case finding implemented in Kenya and home-based HTC [48, 49]. HIV self-testing (HST) is also part of interventions in Zambia and has shown some acceptance and the potential to improve access to HIV testing [50,51,52,53]. However, our study found that HST was unknown to most youth (85 and 80% among women and men, respectively). Its promotion, together with other community-based approaches, is to be encouraged given their potential to increase testing coverage, overcome stigma barriers, and contribute to reducing risky sexual behaviour [54,55,56,57,58]. Concerns regarding their linkage to care for HIV positive cases should be adequately addressed if chosen to be implemented at a large scale.

The positive changes in testing uptake highlighted above among men and non-pregnant women have also been accompanied by a constant gap in the trend of HIV testing coverage between genders, with men being generally less well covered than women. Similar differences among youth were reported in Nigeria, Mozambique, and Uganda [59, 60]. The persistence of higher testing rates among non-pregnant women compared to men may be due to their higher demand of HTC services, caused by a greater perception of HIV risk resulting from their vulnerability and frequent exposures to sexual intercourse with older partners with whom they may have less control over condom use [10, 61]. Women of reproductive age are also generally reported to use primary healthcare more often than men, either for themselves or for their children [62, 63]. As a result, non-pregnant women remain more likely to be suggested an HIV test whenever they interact with health services as part of provider-initiated counselling and testing (PICT), which is widely implemented in government health facilities in Zambia [26, 46, 64]. Moreover, it is possible that existing interventions that target youth, such as youth-friendly services (YFS), might be much more women-specific [65, 66]. Indeed, it has been shown that norms related to masculinity bring men to consider sexual health as a woman’s domain, and therefore believe that it would be inappropriate for them [67]. A recent scoping review focusing on the sub-Sahara African (SSA) region highlighted several other barriers to uptake of HTC among men that might be important to consider even for youth [68, 69]. Among the most common, we find poor knowledge of HIV, fear of testing positive, lack of confidentiality, and other aspects related to the quality of services. Therefore, increasing uptake of testing among young men will require the implementation of interventions that are young men-driven, needs-based, and beneficiary responsive, including implementation of decentralised service delivery models that capture young men in their safe spaces.

Our results showed adolescent girls (non-pregnant) and boys having a lower HIV testing uptake by 2018 (46 and 38%, respectively), compared to young adults. The persistence of this age-based gap in the trend analysis was observed in both multivariate and inequity analysis among both non-pregnant women and men. The proportions achieved in testing coverage among adolescents in 2018 are still far from the testing targets set by the Zambian Ministry of Health for this year (70 and 50% for adolescent girls and boys, respectively) [10]. A recent study in Zambia and several other countries from the SSA region have also reported lower odds of testing among adolescents [21, 33, 59, 60]. Most supported the fact that older age is likely to confer more sexual experience and better knowledge of HIV, which may accordingly improve the perception of the risk and affect the need for HIV testing [21, 60, 70]. Other barriers specific to adolescents include the legal age of consent to HIV testing, stigma, and sanctioning of sexual activity in adolescents; and are important to be highlighted to ensure that they are targets of future interventions that aim to improve coverage of testing among adolescents in Zambia [22, 71, 72]. The ongoing mobilization in Zambia to revise the legal age of consent, currently at 16 years old, needs to be further supported and accelerated [10, 65]. Lowering the age of consent below 16 years old is associated with increased testing for adolescents (11% increase in national testing coverage, 95%CI:7.2–14.8%), as suggested in a systematic review that included several high burden countries [73, 74].

Of the other determinants analysed, having reported HIV-related stigma was associated with lower odds of HTC among non-pregnant sexually active women. The negative impact of stigma has been noted by several other authors and remains a challenge for any HIV program [75, 76]. However, it should be recognized that the scaling up of HIV prevention and treatment services, especially in a universal ‘test and treat’ approach, could help reduce HIV-related stigma in the community through several pathways and improve access to these services [77, 78]. We also found strong evidence of higher odds of HIV testing among the most educated women, consistent with other studies on youth in the SSA region [21, 33, 59]. The education-based inequity widened in the last survey, mostly among non-pregnant women, indicating the need to reach the least educated youths. Other sub-groups of disadvantaged young people who were identified from the inequity analysis require continual attention to ensure improvement of the testing coverage among youth in Zambia.

The results from this study suggest some critical actions from programme implementers and researchers to ensure better access to HTC for youth in Zambia. These include the scaling-up of mobile testing and strengthening of alternative community-based approaches such as HIV self-testing, which has shown some acceptance and potential to clients who are less easy to reach through the government health facilities. The development of gender-sensitive HTC services and less coercive strategies to sustain the gain in testing uptake among men in a union are also important to consider. Finally, the warning about barriers associated with the access to sexual health and HIV services through YFS in a recent study from Brazil [79], and the scarcity of evidence supporting the progress made since their introduction in Zambia, suggest that more research will help to demonstrate their contribution and yield.

Conclusion

Overall, the improvement observed in HTC among Zambian youth is encouraging, with 65% of women and 49% of men knowing their status, although it is still far from the 95% goal envisioned by the UNAIDS in 2030. Therefore, renewed efforts are needed to close the gaps observed among men in general, non-pregnant and less educated adolescent girls, and young women. Sustaining the gains obtained from existing HTC services by addressing barriers such as stigma and offering gender and adolescent-sensitive services is required, in addition to the scaling up of most effective community-based testing approaches. Despite the hope stemming from the recent mobilization to prioritize adolescent health in the country, much attention should be invested in rigorously tracking progress in access to HIV prevention and care services to ensure the reach, effectiveness, and sustainability of implemented strategies, as well as headway toward ensuring that youth live free of HIV and can contribute to the prosperity of the country.

Availability of data and materials

Required permission was obtained from the DHS programme to access the data analysed for this study. All data and DHS-related materials used are available from the website: https://dhsprogram.com/.

Abbreviations

- AGAPE:

-

Adolescent girls accessing prevention and education

- AGYW:

-

Adolescent girls and young women

- AIDS:

-

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- aOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CHCT:

-

Couple HIV counselling and testing

- cOR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- DHS:

-

Demographic and health survey

- DREAMS:

-

Determined, resilient, empowered, AIDS-free, mentored, and safe

- GFATM:

-

Global fund to fight tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS and malaria

- GHC:

-

Government health centres

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HTC:

-

HIV testing and counselling

- HST:

-

HIV self-testing

- LMIC:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- NASF:

-

National AIDS strategic framework

- MC:

-

Mobile clinic

- PEPFAR:

-

United States president’s emergency plan for AIDS relief

- PICT:

-

Provider-initiated counselling and testing

- SM:

-

Supplementary materials

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- STI:

-

Sexually transmitted infection

- UNAIDS:

-

Joint United Nations programme on HIV/AIDS

- UNICEF:

-

United Nations children’s fund

- VCT:

-

Voluntary counselling and testing

- VMMC:

-

Voluntary medical male circumcision

- YFS:

-

Youth-friendly services

References

Global health estimates: Leading causes of death. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-leading-causes-of-death. Accessed 10 Dec 2020.

HIV/AIDS Key facts. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids. Accessed 10 Dec 2020

Bernstein M, Sessions M. A trickle or a Flood: Commitments and Disbursement for HIV/AIDS from the Global Fund, PEPFAR, and the World Bank’s Multi-country AIDS program (MAP). In: HIV/AIDS monitor. Center for Global Development. 2007. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/trickle-or-flood-commitments-and-disbursement-hivaids-global-fund-pepfar-and-world-banks. Accessed 15 Oct 2020.

UNAIDS, WHO, UNICEF. UNAIDS, UNICEF and WHO urge countries in western and central Africa to step up the pace in the response to HIV for children and adolescents. In: Press release. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2019. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/pressreleaseandstatementarchive/2019/january/20190116_PR_WCA_children_adolescents. Accessed 22 Oct 2020

Children, HIV and AIDS: The world today and in 2030. New York: UNICEF; 2018. https://data.unicef.org/resources/children-hiv-and-aids-2030/. Accessed 22 Oct 2020.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Start Free Stay Free AIDS Free - 2019 report. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2019.

Zambia Statistics Agency, Ministry of Health (MOH) Zambia, and ICF. Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2018. Lusaka, Zambia,and Rockville, Maryland, USA: Zambia Statistics Agency, Ministry of Health, and ICF; 2019.

AIDSinfo. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2020. http://aidsinfo.unaids.org/. Accessed 28 Mar 2020.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Zambia. In: Country factsheets. UNAIDS. 2019. https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/zambia. Accessed 21 Apr 2020.

National HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Council Zambia. National AIDS Strategic Framework (NASF) 2017-2021. Lusaka: National HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Council; 2017.

McKinnon LR, Karim QA. Factors driving the HIV epidemic in southern Africa. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2016;13(3):158–69.

Mojola SA, Wamoyi J. Contextual drivers of HIV risk among young African women. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(Suppl 4):e25302.

Saul J, Bachman G, Allen S, Toiv NF, Cooney C, Beamon T. The DREAMS core package of interventions: a comprehensive approach to preventing HIV among adolescent girls and young women. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0208167.

Abdool Karim Q, Baxter C, Birx D. Prevention of HIV in adolescent girls and Young women: key to an AIDS-free generation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75:S17–26.

Miller WC, Lesko CR, Powers KA. The HIV care cascade: simple concept, complex realization. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41(1):41–2.

Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Horn T, Thompson MA. The state of engagement in HIV care in the United States: from cascade to continuum to control. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(8):1164–71.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). 90–90–90 - An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2014.

Govindasamy D, Ferrand RA, Wilmore SM, Ford N, Ahmed S, Afnan-Holmes H, et al. Uptake and yield of HIV testing and counselling among children and adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(1):20182.

The INSIGHT START Study Group. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:795–807.

Wong VJ, Murray KR, Phelps BR, Vermund SH, McCarraher DR. Adolescents, young people, and the 90–90–90 goals: a call to improve HIV testing and linkage to treatment. AIDS. 2017;31:S191–4.

Mwaba K, Mannell J, Burgess R, Sherr L. Uptake of HIV testing among 15–19-year-old adolescents in Zambia. AIDS Care. 2020;32(sup2):183–92.

Qiao S, Zhang Y, Li X, Menon JA. Facilitators and barriers for HIV-testing in Zambia: a systematic review of multi-level factors. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0192327.

Ministry of Health, Zambia. Zambia Population-based HIV Impact Assessment (ZAMPHIA) 2016: Final Report. Lusaka: Ministry of Health; 2019.

Central Statistical Office (CSO) [Zambia], Ministry of Health (MOH) [Zambia], and ICF International. Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2013–14. Rockville, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Office, Ministry of Health, and ICF International; 2014.

Republic of Zambia. HIV Testing and Counselling Implementation Plan (2014–2016). Lusaka: National HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Council; 2015.

Ministry of Health Zambia. Zambia consolidated guidelines for treatment and prevention of HIV infection. Lusaka: National HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Council; 2017.

Ministry of Health Zambia. Zambia consolidated guidelines for HIV treatment and prevention 2018. Lusaka: National HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Council; 2018.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). A super fast-track framework for ending aids in children, adolescents, and young women by 2020. UNAIDS. 2016. https://free.unaids.org/. Accessed 18 Mar 2020.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). All In initiative for adolescents. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2015.

Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4):1–28.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10.

Barros AJD, Victora CG. Measuring coverage in MNCH: determining and interpreting inequalities in coverage of maternal, newborn, and child health interventions. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001390.

Bekele YA, Fekadu GA. Factors associated with HIV testing among young females; further analysis of the 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey data. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0228783.

Lakhe NA, Diallo Mbaye K, Sylla K, Ndour CT. HIV screening in men and women in Senegal: coverage and associated factors; analysis of the 2017 demographic and health survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:1.

Menna T, Ali A, Worku A. Factors associated with HIV counseling and testing and correlations with sexual behavior of teachers in primary and secondary schools in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. HIVAIDS (Auckl). 2015;7:197–208.

Yaya S, Olarewaju O, Oladimeji KE, Bishwajit G. Determinants of prenatal care use and HIV testing during pregnancy: a population-based, cross-sectional study of 7080 women of reproductive age in Mozambique. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:354.

World Bank. Population estimates and projections, DataBank. 2020. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/population-estimates-and-projections. Accessed 11 Jul 2020.

Equiplot. International Center for Equity in Health, Pelotas. https://www.equidade.org/equiplot. Accessed 8 Dec 2020.

World Health Organization. Handbook on health inequality monitoring: with a special focus on low- and middle-income countries. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Herlihy JM, Hamomba L, Bonawitz R, Goggin CE, Sambambi K, Mwale J, et al. Integration of PMTCT and antenatal services improves combination antiretroviral therapy uptake for HIV-positive pregnant women in southern Zambia: a prototype for option B+? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70(4):e123–9.

Muyunda B, Mee P, Todd J, Musonda P, Michelo C. Estimating levels of HIV testing coverage and use in prevention of mother-to-child transmission among women of reproductive age in Zambia. Arch Public Health. 2018;76(1):80.

Central Statistical Office (CSO), Ministry of Health (MOH), Tropical Diseases Research Centre (TDRC), University of Zambia, and Macro International Inc. Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2007. Calverton, Maryland, USA: CSO and Macro International Inc.; 2009.

Musheke M, Bond V, Merten S. Couple experiences of provider-initiated couple HIV testing in an antenatal clinic in Lusaka, Zambia: lessons for policy and practice. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:97.

Wall KM, Kilembe W, Nizam A, Vwalika C, Kautzman M, Chomba E, et al. Promotion of couples’ voluntary HIV counselling and testing in Lusaka, Zambia by influence network leaders and agents. BMJ Open. 2012;2(5):e001171.

Inambao M, Kilembe W, Canary LA, Czaicki NL, Kakungu-Simpungwe M, Chavuma R, et al. Transitioning couple’s voluntary HIV counseling and testing (CVCT) from stand-alone weekend services into routine antenatal and VCT services in government clinics in Zambia’s two largest cities. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0185142.

Zambia. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, Geneva. 2017. https://data.theglobalfund.org/investments/location/ZMB. Accessed 9 Nov 2020.

Hensen, B. Increasing men's uptake of HIV-testing in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of interventions and analyses of population-based data from rural Zambia. PhD thesis, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine; 2016. DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17037/PUBS.02531234

Kose J, Tiam A, Ochuka B, Okoth E, Sunguti J, Waweru M, et al. Impact of a comprehensive adolescent-focused case finding intervention on uptake of HIV testing and linkage to care among adolescents in Western Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;79(3):367–74.

Shanaube K, Schaap A, Chaila MJ, Floyd S, MacKworth-Young C, Hoddinott G, et al. Community intervention improves knowledge of HIV status of adolescents in Zambia: findings from HPTN 071-PopART for youth study. AIDS. 2017;31:S221–32.

Bwalya C, Simwinga M, Hensen B, Gwanu L, Hang’andu A, Mulubwa C, et al. Social response to the delivery of HIV self-testing in households: experiences from four Zambian HPTN 071 (PopART) urban communities. AIDS Res Ther. 2020;17(1):32.

Hatzold K, Gudukeya S, Mutseta MN, Chilongosi R, Nalubamba M, Nkhoma C, et al. HIV self-testing: breaking the barriers to uptake of testing among men and adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa, experiences from STAR demonstration projects in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(S1):e25244.

Mulubwa C, Hensen B, Phiri MM, Shanaube K, Schaap AJ, Floyd S, et al. Community based distribution of oral HIV self-testing kits in Zambia: a cluster-randomised trial nested in four HPTN 071 (PopART) intervention communities. Lancet HIV. 2018;6(2):e81–92.

Zanolini A, Chipungu J, Vinikoor MJ, Bosomprah S, Mafwenko M, Holmes CB, et al. HIV self-testing in Lusaka Province, Zambia: acceptability, comprehension of testing instructions, and individual preferences for self-test kit distribution in a population-based sample of adolescents and adults. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2018;34(3):254–60.

Barnabas RV, van Rooyen H, Tumwesigye E, Brantley J, Baeten JM, van Heerden A, et al. Uptake of antiretroviral therapy and male circumcision after community-based HIV testing and strategies for linkage to care versus standard clinic referral: a multisite, open-label, randomised controlled trial in South Africa and Uganda. Lancet HIV. 2016;3(5):e212–20.

Chamie G, Clark TD, Kabami J, Kadede K, Ssemmondo E, Steinfeld R, et al. A hybrid mobile HIV testing approach for population-wide HIV testing in rural East Africa: an observational study. Lancet HIV. 2016;3(3):e111–9.

Coates TJ, Kulich M, Celentano DD, Zelaya CE, Chariyalertsak S, Chingono A, et al. Effect of community-based voluntary counselling and testing on HIV incidence and social and behavioural outcomes (NIMH project accept; HPTN 043): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(5):e267–77.

Feyissa GT, Lockwood C, Munn Z. The effectiveness of home-based HIV counseling and testing on reducing stigma and risky sexual behavior among adults and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analyses. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13(6):318–72.

Sharma M, Ying R, Tarr G, Barnabas R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of community and facility-based HIV testing to address linkage to care gaps in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature. 2015;528(7580):S77–85.

Ajayi AI, Awopegba OE, Adeagbo OA, Ushie BA. Low coverage of HIV testing among adolescents and young adults in Nigeria: implication for achieving the UNAIDS first 95. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0233368.

Asaolu IO, Gunn JK, Center KE, Koss MP, Iwelunmor JI, Ehiri JE. Predictors of HIV testing among youth in sub-Saharan Africa: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164052.

Nwachukwu CE, Odimegwu C. Regional patterns and correlates of HIV voluntary counselling and testing among youths in Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2011;15(2):131–46.

Cleary PD, Mechanic D, Greenley JR. Sex differences in medical care utilization: an empirical investigation. J Health Soc Behav. 1982;23(2):106–19.

Yeatman S, Chamberlin S, Dovel K. Women’s (health) work: a population-based, cross-sectional study of gender differences in time spent seeking health care in Malawi. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0209586.

Topp SM, Chipukuma JM, Chiko MM, Wamulume CS, Bolton-Moore C, Reid SE. Opt-out provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling in primary care outpatient clinics in Zambia. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(5):328–335A.

UNAIDS, UNICEF. All in to end the adolescent AIDS epidemic — a progress report. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2016.

Ministry of Community Development Zambia. National Standards and guidelines for youth friendly health services. Lusaka: Ministry of Community Development; 2015.

Kolundzija A. Annotated bibliography: gender norms and youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services. London: ALIGN; 2019.

Hlongwa M, Mashamba-Thompson T, Makhunga S, Hlongwana K. Barriers to HIV testing uptake among men in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. Afr J AIDS Res. 2020;19(1):13–23.

Musheke M, Merten S, Bond V. Why do marital partners of people living with HIV not test for HIV? A qualitative study in Lusaka, Zambia. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):882.

Peltzer K, Matseke G. Determinants of HIV testing among young people aged 18–24 years in South Africa. Afr Health Sci. 2013;13(4):1012–20.

Chanda MM, Perez-Brumer AG, Ortblad KF, Mwale M, Chongo S, Kamungoma N, et al. Barriers and facilitators to HIV testing among Zambian female sex Workers in Three Transit Hubs. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2017;31(7):290–6.

Chikwari CD, Dringus S, Ferrand RA. Barriers to, and emerging strategies for, HIV testing among adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2018;13(3):257–64.

Fox K, Ferguson J, Ajose W, Singh J, Marum E, Baggaley R. Adolescent consent to testing: a review of current policies and issues in sub-Saharan Africa. In: HIV and Adolescents: Guidance for HIV Testing and Counselling and Care for Adolescents Living with HIV. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. Annex. p. 15.

McKinnon B, Vandermorris A. National age-of-consent laws and adolescent HIV testing in sub-Saharan Africa: a propensity-score matched study. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97(1):42–50.

Gesesew HA, Tesfay Gebremedhin A, Demissie TD, Kerie MW, Sudhakar M, Mwanri L. Significant association between perceived HIV related stigma and late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173928.

Hargreaves JR, Krishnaratne S, Mathema H, Lilleston PS, Sievwright K, Mandla N, et al. Individual and community-level risk factors for HIV stigma in 21 Zambian and south African communities: analysis of data from the HPTN071 (PopART) study. AIDS. 2018;32(6):783–93.

Camlin CS, Charlebois ED, Getahun M, Akatukwasa C, Atwine F, Itiakorit H, et al. Pathways for reduction of HIV-related stigma: a model derived from longitudinal qualitative research in Kenya and Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(12):e25647.

Chan BT, Tsai AC, Siedner MJ. HIV treatment scale-up and HIV-related stigma in sub-Saharan Africa: a longitudinal cross-country analysis. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(8):1581–7.

Pastrana-Sámano R, Heredia-Pi IB, Olvera-García M, Ibáñez-Cuevas M, Castro FD, Hernández AV, et al. Adolescent friendly services: quality assessment with simulated users. Rev Saúde Pública. 2020;54:36.

Acknowledgments

We thank the DHS Program for providing access to the Zambian Demographic Health surveys. A.B.H is benefited by a scholarship from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan for his doctoral training at Nagasaki University. The first author wishes to thank Associate Professor Lenka Benova for her contributions in the development of this study. We would like also to thank Dr. Thomas Templeton (http://templetoncopyediting.com) for English language editing.

Funding

This study did not receive funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B.H. designed the research idea and protocol, conducted data analysis, and prepared the manuscript. F.L.C. and M.M. provided input on the study design, contributed to the data analysis, the interpretation of the results, as well as the revision of the manuscript. N.A. and M.M.M. contributed substantially to the interpretation of results and finalization of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The DHS program obtained ethical approval from institutional review boards at Inner City Fund (ICF) International Inc. and the Tropical Diseases Research Centre (TDRC) in Zambia. At the beginning of each survey, every participant was informed that participation in the survey is completely voluntary, the participant has rights to skip any questions and stop the interview any time, and the information in this survey is strictly confidential. For each survey, respondents were asked to provide written informed consent before interview; and data collectors were trained on ethical issues. This study was a secondary analysis of data with no identifying information, and therefore did not require ethical approval from Nagasaki University. This study was complied with Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects jointly issued from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in 2017 in Japan. We also received an authorization to use the Zambian dataset from the DHS Program.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Details on variables used for the analysis; Table S2. Determinants of HIV testing uptake among sexually active non-pregnant young women aged 15–24, Zambia 2018 DHS (N = 2457); and Table S3. Determinants of HIV testing uptake among sexually active young men aged 15–24, Zambia DHS 2018 (N = 3114).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Heri, A.B., Cavallaro, F.L., Ahmed, N. et al. Changes over time in HIV testing and counselling uptake and associated factors among youth in Zambia: a cross-sectional analysis of demographic and health surveys from 2007 to 2018. BMC Public Health 21, 456 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10472-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10472-x