Abstract

Background

HIV/AIDS continues to be a major public health concern for children. Each day, worldwide, approximately 440 children became newly infected with HIV, and 270 children died from AIDS-related causes in 2018. Poor nutrition has been associated with accelerated disease progression, and sufficient dietary diversity is considered a key to improve children’s nutritional status. Therefore, this study aims to 1) examine nutritional status of school-age children living with HIV in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, and 2) identify factors associated with their nutritional status, especially taking their dietary diversity into consideration.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in May 2018 within the catchment area of the National Pediatric Hospital, Cambodia. Data from 298 children and their caregivers were included in the analyses. Using semi-structured questionnaires, face-to-face interviews were conducted to collect data regarding sociodemographic characteristics, quality of life, and dietary diversity. To assess children’s nutritional status, body weight and height were measured. Viral load and duration of antiretroviral therapy (ART) were collected from clinical records. Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to identify factors associated with stunting and wasting.

Results

Of 298 children, nearly half (46.6%) were stunted, and 13.1% were wasted. The mean number of food groups consumed by the children in the past 24 h was 4.6 out of 7 groups. Factors associated with children’s stunting were age (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 2.166, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.151, 4.077), household wealth (AOR 0.543, 95%CI: 0.299, 0.986), duration of receiving ART (AOR 0.510, 95%CI: 0.267, 0.974), and having disease symptoms during the past 1 year (AOR 1.871, 95%CI: 1.005, 3.480). The only factor associated with wasting was being male (AOR 5.304, 95%CI: 2.210, 12.728).

Conclusions

Prevalence of stunting was more than double that of non-infected school-age children living in urban areas in Cambodia. This highlights the importance of conducting nutritional intervention programs, especially tailored for children living with HIV in the country. Although dietary diversity was not significantly associated with children’s nutritional status in this study, the findings will contribute to implementing future nutritional interventions more efficiently by indicating children who are most in need of such interventions in Cambodia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

While there have been great achievements in reducing human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections worldwide, children are still at risk of new infections. According to UNAIDS, the number of new HIV infections among children has been falling continuingly since 2000. Due to the global scale-up of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and the success in preventing mother-to-child transmission, 1.6 million new child HIV infections were averted between 2008 and 2017. However, in 2018, among the estimated 37.9 million people living with HIV worldwide, 1.7 million were children under 15 years old. Each day, worldwide, approximately 440 children became newly infected with HIV, and 270 children died from AIDS-related causes [1].

Poor nutrition has been associated with impaired immunity and accelerated disease progression among children living with HIV [2,3,4]. Infected children are at risk of growth failure [5, 6] as well as developmental and behavioral challenges [7]. Progressive stunting is considered the most common abnormality in children who were infected with HIV perinatally. Deficiencies of several micronutrients such as Vitamin A have been identified as an important factor negatively associated with growth [4, 8].

Recent studies conducted in Asia and Africa reported that, although ART improved the growth of children living with HIV, adjunct nutritional interventions such as nutritional supplementation and nutritional counselling are needed to promote better growth of these children [5, 9, 10]. In fact, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that children living with HIV increase energy intake and maintain a balanced macronutrient distribution for optimal growth and nutrition [11]. A recent systematic review revealed that vitamin A supplementation for HIV-infected infants and children led to a 45% reduction in the risk of all-cause mortality and reduced the likelihood of all-cause morbidity by 31% [8].

Along with micronutrient supplementation, sufficient dietary diversity is considered a key to improving overall nutritional and health status of children living with HIV [12,13,14]. A number of recent studies have explored risk factors for undernutrition, using dietary diversity score developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization [15,16,17,18,19,20]. Dietary diversity score, which consists of a simple count of food groups that an individual has consumed over the preceding 24 h, is considered a proxy for nutrient adequacy of the diet of individuals [21]. Several studies in African countries have revealed that low dietary diversity was associated with malnutrition, while consumption of an adequate variety of food can improve general nutritional status [15, 19, 20]. In order to plan an effective intervention program aimed at improving feeding practices and dietary diversity of children living with HIV, it is crucial to understand their current nutritional status and dietary intake.

Although the majority of children living with HIV reside in sub-Saharan Africa, Cambodia was home for 3300 infected children aged 0–14 in 2018 [1]. Cambodia has been making tremendous strides in HIV prevention and control [22], which has led to the fact that almost all people living with HIV who knew their HIV status were receiving treatment in 2018 [1]. Further, several studies have revealed a variety of health issues faced by HIV-infected adolescents and adults in Cambodia and made recommendations to effectively tackle these issues [23, 24]. However, few studies have been conducted in Cambodia and other Southeast Asian countries to evaluate nutritional status and dietary intake of children living with HIV, especially those of school age. Therefore, this study aimed to 1) examine the nutritional status of school-age children living with HIV in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, and 2) identify factors associated with their nutritional status, especially taking their dietary diversity into consideration.

Methods

Study design and sites

This cross-sectional study was conducted in May 2018 as a baseline survey of a randomized controlled trial, which has been conducted to examine the effectiveness of a daily oral care intervention on the health status of children living with HIV [25]. The study site was within the catchment area of the National Pediatric Hospital, which is the only health facility providing pediatric ART in Phnom Penh.

Study population and recruitment

Out of the participants of the randomized controlled trial, only school-age children infected with HIV were included in this study. The multiple-step recruitment process of the randomized controlled trial has been described in a recent paper [25]. Briefly, children 3 to 15 years of age living with HIV were identified from patient lists of the National Pediatric Hospital. In total, 1113 children were considered eligible for the randomized controlled trial. Selection criteria were (1) aged 3–15 years, (2) possession of a patient ID at the National Pediatric Hospital, and (3) having received ART for at least 3 months prior to the study. Of the eligible children, 337 were selected, using a computerised algorithm by a data analyst, who was not a primary member of the research team. Selected children were recruited for the trial and participated in the baseline survey.

For this study, data from 298 children and their caregivers were included in the analysis after excluding 31 children below school age (under 6 years old) and eight children with missing data related to dietary diversity. There was no statistically significant difference in socio-demographic characteristics between the 306 children (including eight children with missing data) and 298 children, who were included in the analysis (e.g. age: p-value = 0.981, viral load: p-value = 0.959, ART length: p-value = 0.898). The sample size was larger than the required sample size of 271, which was calculated using Raosoft online sample size calculator (an estimated population of children living with HIV in Phnom Penh of 1650, 30% rate of stunting, 5% margin of error, and 99% confidence interval (CI)).

Data collection

Questionnaire

Face-to-face interviews were conducted with the selected children and their caregivers, using semi-structured questionnaires. The questionnaire for children consisted of items regarding socio-demographic characteristics, HIV symptoms, and overall health and oral health quality of life. The questionnaire for caregivers included questions regarding socio-demographic characteristics and dietary diversity. Both questionnaires were developed based on existing tools used in previous studies and an existing guideline [21, 26, 27].

Dietary diversity, a characteristic of the quality of the diet, was assessed using a dietary diversity questionnaire, which was developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization. It is a proxy for nutrient adequacy of the diet of individuals and consists of a simple count of food groups that an individual has consumed over the preceding 24 h [21]. In this study, caregivers were asked if their child had consumed the food items described in Table 1.

To examine children’s well-being related diet, oral health-related quality of life was measured using the Child Perceptions Questionnaire [27, 28]. The questionnaire has been validated in Cambodia, and contains 16 items across four subscales: oral symptoms, functional limitations, emotional well-being, and social well-being. Responses for each item were rated on a five-point Likert scale: “never” = 0, “once or twice”=1, “sometimes” = 2, “often” = 3, “every day or almost every day”=4. The total score ranged from 0 to 64, and a higher score indicates worse oral health-related quality of life.

Overall health-related quality of life was measured using Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 (PedsQL™ 4.0), which has been validated for children living with HIV [26]. The inventory contains 23 items across four subscales: physical, emotional, social, and school functioning. The five-point Likert scale for each item was: “never” = 0, “almost never” = 1, “sometimes” = 2, “often” = 3, “almost always” = 4. Items were reversed scored and linearly transformed to a 0–100 scale (100, 75, 50, 25, and 0). The sum of all the items over the number of items answered on all the scales was calculated, and the total score ranged 0–100. A higher total score indicated a better quality of life.

Health status

Body weight and height were measured by nursing staff of the National Pediatric Hospital, Cambodia, using electronic scales and a stadiometer to examine children’s nutritional status. Clinical records of children, including viral load, duration of ART use, and history of opportunistic infections, were collected by research assistants from the registered documents of the National Pediatric Hospital.

Data management and statistical analysis

Open Data Kit 2.0 was used to directly record study participants’ responses to questionnaires (available at https://opendatakit.org/use/2_0_tools/). Body weight, height, and clinical data were recorded on paper-based forms, and entered electronically by data management assistants at the National Pediatric Hospital.

To assess the dietary diversity of children, a dietary diversity score (DDS) was calculated by summing the number of food groups consumed by each child over the previous 24-h recall period. In the Infant and Young Child Feeding guidelines published by the United Nations, dietary diversity scores of pre-school children are dichotomized: children who had at least four of the seven food groups were considered to have adequately diversified dietary intake [29]. In our study, we dichotomized the score using median as there is no recommended cut-off points for our study population (school-age children) [16,17,18,19,20,21]. The median of the children’s dietary diversity scores was calculated to determine the cutoff point between lower and higher dietary diversity. Based on the median value, children who consumed less than five food groups were classified into a lower dietary diversity group, and five or more into a higher dietary diversity group.

For anthropometric data analysis, z-scores of height for age and body mass index (BMI) for age were obtained using WHO Anthro Plus software (available at http://www.who.int.growthref/tools/en). Children whose height for age z-score was below − 2 standard deviations (SD) were considered as stunted. Children whose BMI for age z-score was below -2SD were considered as wasted.

Children were assigned to socio-economic status quartiles based on household assets and housing characteristics determined by principal component analysis [30].

Descriptive statistics were conducted to examine children’s socio-demographic characteristics and dietary diversity. Two multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to identify factors associated with stunting and wasting. In each analysis, the following independent variables were included: age, sex, household wealth, duration of receiving ART, viral load, history of disease symptoms (based on clinical records of the past year), quality of life, oral health quality of life, and dietary diversity. There was no multicollinearity among the independent variables. Educational status was excluded from the regression analyses because most of the children (95.6%) were enrolled in formal school education. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA 14.0.

Results

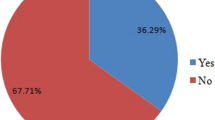

A total of 298 children aged 6–15 living with HIV in Phnom Penh were included in the analyses for this study. Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants are described in Table 2. Out of 298 children, nearly half (139, 46.6%) were stunted, and 39 (13.1%) were wasted. Caregivers of most of the children (89.4%) reported that their child was infected with HIV through mother-to-child transmission, one was infected through a medical accident, and the others had no idea about the transmission route (data not shown). The length of time the children had been receiving ART ranged from 3 to 191 months. The majority of the children (79.5%) had a history of disease symptoms such as fever, cough or diarrhea within the past year.

Children’s dietary diversity is shown in Table 3. During the past 24 h, the majority of the children consumed foods from Group 1 (98.3%), 4 (98.0%), 6 (81.2%) and 7 (72.8%). About half took Group 5 (56.7%), and a third took Group 3 (36.9%). Only 16.1% of the children had foods from Group 2. The mean number of food groups consumed by the children were 4.6 out of 7 groups (median = 5, interquartile range = 1, data not shown). Other foods that were not included in the dietary diversity score, including fats, sugary foods, and condiments for flavor, were taken by the majority of children (83.2%). More than half of the children (53.7%) had sugary food such as chocolates, cookies, and cakes. None of the food groups was significantly associated with children’s stunting and wasting status.

Detailed food items that were consumed by children are shown in Fig. 1. No significant differences were found in the consumption of each food item between stunted and not stunted children (data not shown).

Factors associated with children’s stunting were identified by multiple logistic regression analysis (Table 4). Children in the oldest age group (13–15) were 2.2 times more likely to be stunted compared to those in the youngest age group (6–10) (AOR 2.166, 95%CI: 1.151, 4.077). Children who belonged to the middle household wealth group were 46% less likely to be stunted compared to those in the lowest wealth group (AOR 0.543, 95%CI: 0.299, 0.986). Longer duration of receiving ART was significantly associated with less stunting: children who had received ART for the longest period (105–191 months) were 49% less likely to be stunted compared to those with the shortest ART duration of 3–62 months (AOR 0.510, 95%CI: 0.267, 0.974). Children who had disease symptoms during the past year were almost twice more likely to be stunted compared to those without any disease symptoms (AOR 1.871, 95%CI: 1.005, 3.480).

Factors associated with wasting were also examined through multiple logistic regression analysis (Table 4). Only one factor was significantly associated with children’s wasting: male children were 5.3 times more likely to be wasted compared to female children (AOR 5.304, 95%CI: 2.210, 12.728).

Discussion

This study examined nutritional status and dietary diversity of school-age children living with HIV in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Nearly half of the children who participated in this study were stunted, and one-seventh were wasted. Factors associated with stunting were higher age, lower household wealth, shorter duration of receiving ART, and having disease symptoms during the past year. Only one factor, being male, was significantly associated with wasting. Dietary diversity, which was measured by a dietary diversity score, as well as any of the individual food items included in the score, were not associated with children’s nutritional status.

Prevalence of stunting was more than double among our study participants compared to non-infected school-age children living in urban areas in Cambodia. A recent study revealed that the overall prevalence of stunting among Cambodian children aged 6–17 years was 33.2% in 2014/2015, and that stunting was more prevalent in children living in rural areas than in children living in urban areas (36.4% vs. 20.4%, respectively) [31]. The high prevalence of stunting among our study participants coincides with a report indicating that HIV-infection was associated with growth delays in both weight and height [32, 33]. As children living with HIV are more seriously affected by malnutrition compared to non-infected children [2,3,4], implementing tailored nutrition programs, targeting children living with HIV, is highly recommended.

This study revealed that older age was associated with stunting, but that receiving ART for a longer duration could be a protective factor against stunting. This finding is similar to results of a recent study conducted in Thailand, which demonstrated that the younger the children at ART initiation, the greater the effect on height-growth velocity regardless of the ART regimen [34]. Another recent study revealed that HIV infection was associated with not only stunting but also low lumbar spine bone density among children living with HIV in Zimbabwe and that younger age at initiation of ART predicted high bone mineral density [35]. There are additional studies which stress the importance of initiating ART before irreversible stunting has occurred [36]. As the WHO and previous studies recommend, starting ART as soon as children are diagnosed with HIV and continuation of the treatment is crucial not only for the prevention of disease progression but also for prevention of growth retardation.

In this study, the dietary diversity score and any of the food groups and food items that constitute dietary diversity score, showed no significant associations with children’s nutritional status. On average, children consumed five out of seven food groups within the 24 h before the survey. This is slightly higher than four groups, which was reported by one of the few dietary diversity studies in Cambodia, targeting children living in rural areas in 2012 [37]. However, considering the high prevalence of stunting, improvement in both the quality and quantity of the diet of children living with HIV as well as relevant factors that support healthy dietary habit are vital. To identify growth delay as early as possible, it is recommended that nutritional assessment, including appetite and opportunistic infections, needs to be conducted [38]. Also, the WHO recommends that nutritional assessment and support should be an integral part of the care plan for children living with HIV [11]. Such support needs to include interventions to improve oral health as untreated dental caries and a delayed eruption of permanent teeth are associated with underweight and stunting among children in Cambodia, Indonesia and Lao PDR [39]. The timing of such nutritional interventions is also important: a recent study suggested that the first year on ART could be the best period to conduct nutritional interventions for children living with HIV to optimize their growth in the long term [40].

Findings from this study should be considered in the context of some limitations. First, because interview data were self-reported by children and their caregivers, there was a possibility of recall bias and courtesy bias. To minimize these biases, data were confirmed with clinical record whenever possible, and interviews were conducted by experienced and trained interviewers with on-site supervision. Second, dietary diversity was measured by questionnaire and no detailed exams such as micronutrient blood testing were conducted. Third, although it is common to dichotomize dietary diversity score of study population to evaluate individuals’ dietary diversity, small statistical difference between lower and higher dietary diversity groups could reduce the statistical likelihood of this variable being related to outcome variables, i.e. stunting and wasting. Therefore, to double check our results, we run other regression analyses, treating the dietary diversity score as a continuous variable. As a result, it was confirmed that dietary diversity of our study population was not significantly associated with stunting and wasting.

Despite these limitations, this is one of the few studies that examined nutritional status and dietary diversity of children living with HIV in Cambodia. Although dietary diversity was not associated with nutritional status, findings of this study will assist in strengthening future intervention programs, targeting children living with HIV in Cambodia and other resource-limited countries.

Conclusions

This is one of the few studies examining nutritional status and dietary diversity of school-age children living with HIV in Cambodia. Prevalence of stunting among our study participants was more than double that of non-infected school-age children living in urban areas in Cambodia.

This highlights the importance of conducting nutritional intervention programs especially tailored for children living with HIV in the country. Although dietary diversity was not significantly associated with children’s nutritional status in this study, other factors such as age, household wealth, duration of receiving ART, and history of having disease symptoms during the past year were found to be important factors for stunting. These findings will contribute to implementing future nutritional interventions more efficiently by identifying children who are most in need of such interventions in Cambodia and other resource-limited countries.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral therapy

- CI:

-

95% confidence interval

- DDS:

-

Dietary diversity score

- PedsQLTM 4.0:

-

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS): UNAIDS Data 2019. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2019/2019-UNAIDS-data (2019). Accessed 15 Jan 2020.

Ramteke SM, Shiau S, Foca M, Strehlau R, Pinillos F, Patel F, et al. Patterns of growth, body composition, and lipid profiles in a south African cohort of human immunodeficiency virus-infected and uninfected children: a cross-sectional study. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2018;7(2):143–50.

Chiabi A, Lebela J, Kobela M, Mbuagbaw L, Obama MT, Ekoe T. The frequency and magnitude of growth failure in a group of HIV-infected children in Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;11:15.

Arpadi SM. Growth failure in children with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;25(Suppl 1):S37–42 Review.

Sunguya BF, Poudel KC, Mlunde LB, Urassa DP, Yasuoka J, Jimba M. Poor nutrition status and associated feeding practices among HIV-positive children in a food secure region in Tanzania: a call for tailored nutrition training. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e98308.

Musoke PM, Mudiope P, Barlow-Mosha LN, Ajuna P, Bagenda D, Mubiru MM, et al. Growth, immune and viral responses in HIV infected African children receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2010 Aug 6;10:56.

Sherr L, Hensels IS, Tomlinson M, Skeen S, Macedo A. Cognitive and physical development in HIV-positive children in South Africa and Malawi: a community-based follow-up comparison study. Child Care Health Dev. 2018;44(1):89–98.

Visser ME, Durao S, Sinclair D, Irlam JH, Siegfried N. Micronutrient supplementation in adults with HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5:CD003650.

Mwiru RS, Spiegelman D, Duggan C, Seage GR 3rd, Semu H, Chalamilla G, et al. Growth among HIV-infected children receiving antiretroviral therapy in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. J Trop Pediatr. 2014;60(3):179–88.

Shet A, Bhavani PK, Kumarasamy N, Arumugam K, Poongulali S, Elumalai S, et al. Anemia, diet and therapeutic iron among children living with HIV: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:164.

WHO. Guidelines for an integrated approach to the nutritional care of HIV-infected children (6 months-14 years): handbook, chart booklet and guideline for country adaptation: World Health Organizationhttp://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/hivaids/9789241597524/en/. Accessed 15 Jan 2020; 2009.

Martín-Cañavate R, Sonego M, Sagrado MJ, Escobar G, Rivas E, Ayala S, et al. Dietary patterns and nutritional status of HIV-infected children and adolescents in El Salvador: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0196380.

Shiau S, Webber A, Strehlau R, Patel F, Coovadia A, Kozakowski S, et al. Dietary inadequacies in HIV-infected and uninfected school-aged children in Johannesburg, South Africa. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;65(3):332–7.

Mpontshane N, Van den Broeck J, Chhagan M, Luabeya KKA, Johnson A, Bennish ML. HIV infection is associated with decreased dietary diversity in south African children. J Nutr. 2008;138(9):1705–11.

Arimond M, Ruel MT. Dietary diversity is associated with child nutritional status: evidence from 11 demographic and health surveys. J Nutr. 2004;134(10):2579–85.

Berhane HY, Jirström M, Abdelmenan S, Berhane Y, Alsanius B, Trenholm J, et al. Social stratification, diet diversity and malnutrition among preschoolers: a survey of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Nutrients. 2020;12(3):712.

Fahim SM, Das S, Gazi MA, Alam MA, Mahfuz M, Ahmed T. Evidence of gut enteropathy and factors associated with undernutrition among slum-dwelling adults in Bangladesh. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;111(3):657–66.

Ali Z, Abu N, Ankamah IA, Gyinde EA, Seidu AS, Abizari AR. Nutritional status and dietary diversity of orphan and non - orphan children under five years: a comparative study in the Brong Ahafo region of Ghana. BMC Nutr. 2018;4:32.

Huang M, Sudfeld C, Ismail A, Vuai S, Ntwenya J, Mwanyika-Sando M, et al. Maternal dietary diversity and growth of children under 24 months of age in rural Dodoma, Tanzania. Food Nutr Bull. 2018;39(2):219–30.

Sié A, Tapsoba C, Dah C, Ouermi L, Zabre P, Bärnighausen T, et al. Dietary diversity and nutritional status among children in rural Burkina Faso. Int Health. 2018;10(3):157–62.

Macias YF, Glasauer P. Guidelines for assessing nutrition-related knowledge, attitudes and practices. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2014.

Vun MC, Fujita M, Rathavy T, Eang MT, Sopheap S, Sovannarith S, et al. Achieving universal access and moving towards elimination of new HIV infections in Cambodia. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(1):18905.

Yi S, Tuot S, Pal K, Khol V, Sok S, Chhoun P, et al. Characteristics of adolescents living with HIV receiving care and treatment services in antiretroviral therapy clinics in Cambodia: descriptive findings from a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:781.

Chhoun P, Tuot S, Harries AD, Kyaw NTT, Pal K, Mun P, et al. High prevalence of non-communicable diseases and associated risk factors amongst adults living with HIV in Cambodia. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0187591.

Kikuchi K, Yasuoka J, Tuot S, Yem S, Chhoun P, Okawa S, et al. Improving overall health of children living with HIV through an oral health intervention in Cambodia: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):673.

Varni JW, Seid M, Rode CA. The PedsQL: measurement model for the pediatric quality of life inventory. Med Care. 1999;37(2):126–39 PMID: 10024117.

WHO. Oral health surveys: basic methods – 5th edition. Geneva: WHO; 2013.

Turton BJ, Thomson WM, Foster Page LA, Saub R, Ishak AR. Responsiveness of the child perceptions Questionnaire11-14 for Cambodian children undergoing basic dental care. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2015;25(1):2–8.

World Health Organization; UNICEF; USAID; AED; UCDAVIS; IFPRI. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: part 2: measurement; 2010. p. 81. Available online: https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/9789241599290/en/ (Accessed on 24 Apr 2020).

Vyas S, Kumaranayake L. Constructing socio-economic status indices: how to use principal components analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21(6):459–68.

Horiuchi Y, Kusama K, Kanha S, Yoshiike N, FIDR research team. Urban-rural differences in nutritional status and dietary intakes of school-aged children in Cambodia. Nutrients. 2018;11(1):14.

McKinney RE Jr, Robertson JW. Effect of human immunodeficiency virus infection on the growth of young children. Duke pediatric AIDS clinical trials unit. J Pediatr. 1993;123(4):579–82.

Miller TL, Evans SJ, Orav EJ, Morris V, McIntosh K, Winter HS. Growth and body composition in children infected with the human immunodeficiency virus-1. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;57(4):588–92.

Traisathit P, Urien S, Le Coeur S, Srirojana S, Akarathum N, Kanjanavanit S, et al. Impact of antiretroviral treatment on height evolution of HIV infected children. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19(1):287.

Gregson CL, Hartley A, Majonga E, McHugh G, Crabtree N, Rukuni R, et al. Older age at initiation of antiretroviral therapy predicts low bone mineral density in children with perinatally-infected HIV in Zimbabwe. Bone. 2019;125:96–102.

Feucht UD, Van Bruwaene L, Becker PJ, Kruger M. Growth in HIV-infected children on long-term antiretroviral therapy. Trop Med Int Health. 2016;21(5):619–29.

Reinbott A, Schelling A, Kuchenbecker J, Jeremias T, Russell I, Kevanna O, et al. Nutrition education linked to agricultural interventions improved child dietary diversity in rural Cambodia. Br J Nutr. 2016;116(8):1457–68.

WHO. WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-forage: methods and development: World Health Organizationhttp://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/technical_report/en/ Accessed 15 Jan 2020; 2006.

Dimaisip-Nabuab J, Duijster D, Benzian H, Heinrich-Weltzien R, Homsavath A, Monse B, et al. Nutritional status, dental caries and tooth eruption in children: a longitudinal study in Cambodia, Indonesia and Lao PDR. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):300.

Jesson J, Ephoevi-Ga A, Desmonde S, Ake-Assi MH, D'Almeida M, Sy HS, et al. Growth in the first 5 years after antiretroviral therapy initiation among HIV-infected children in the IeDEA west African pediatric cohort. Trop Med Int Health. 2019;24(6):775–85.

Acknowledgments

We heartily thank all the children and their caregivers who participated in this study. In addition, we are grateful to all the experts who have been dedicated to this study, especially to Dr. Mariko Nishikitani, Dr. Rieko Izukura, and Dr. Fumihiko Yokota for their technical advice. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP17H04658.

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP17H04658. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, interpretation of data, decision to publish, or writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JY contributed to the study design, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. KK and YS conceived the study, developed the study protocol and questionnaires, and supervised data collection. SO contributed to the study design and improved the manuscript. ST, MM, CH, PC, SY, and KY contributed to the study design and conducted data collection. TM provided guidance to improve the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval of the randomized controlled trial, including this baseline survey, was obtained from the National Ethics Committee for Health Research, Ministry of Health, Cambodia (289NECHR) and Research Ethics Committee of Kyushu University (29067). Before data collection, written informed consent was obtained from all caregivers, and assent to participate in the study was obtained from all children.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yasuoka, J., Yi, S., Okawa, S. et al. Nutritional status and dietary diversity of school-age children living with HIV: a cross-sectional study in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. BMC Public Health 20, 1181 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09238-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09238-8