Abstract

Background

Understanding the burden and determinants of suicide during adolescence is key to achieving global health goals. We examined the prevalence and determinants of self-reported suicidal ideation and attempts among younger (13–15 years) and older adolescents (16–17 years).

Methods

Pooled prevalence estimates with 95% confidence interval, were calculated for suicide ideation and attempts for 118 surveys from 90 countries that administered the Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS) to adolescents (13–17 years of age) from 2003 to 2017. Indicators (including individual and social factors) associated with suicidal ideation and attempts were determined from multivariable linear regressions on key outcomes.

Results

The prevalence of suicidal ideation representing 397,299 adolescents (51.3% female) was significantly higher among girls than boys whereas attempts did not differ by age or sex. Being bullied, or having no close friends was associated with suicidal ideation among girls 13–15 years and 16–17 years, respectively. Among all boys, being in a fight and having no close friends was associated with suicidal ideation with the addition of serious injury for boys 13–15 years. Common to all younger adolescents was an association of suicide attempt with being bullied and having had a serious injury. Among young boys, having no close friends was an additional indicator for suicide attempt. Having no close friends was associated with suicide attempt in older adolescents with the addition to being bullied in older girls and serious injury in older boys.

Conclusions

Building positive social relationships with peers and avoiding serious injury appear key to suicide prevention strategies for vulnerable adolescents. Targeted programs by age group and sex for such indicators could improve mental health during adolescence in low and middle-income countries, given the diverse risk profiles for suicidal ideation and attempts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Death by intentional self-directed injury, suicide, is an indicator for Sustainable Development Goal 3.4.2 [1]. Suicide amid young people (15–29 years) accounts for one-third of all suicides globally and is the second leading cause of death in this age group [2]. Global estimates from the first decade (2000–2009), for suicide mortality in early adolescents (10–14 year of age) is 1.52 per 100,000 for boys and 0.94 per 100,000 for girls which jump to 10 per 100,000 during late adolescence (15–19 year of age) [3, 4]. Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis of 24 studies which assessed risk and protective factors of suicidal behaviours in adolescents and young adults (14–26 years) suggested that females presented with a higher risk of suicide attempt (Odds Ratio (OR): 1.96, 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.54–2.50), as compared to males [5]. Suicidal behaviour includes ideation (thinking about killing oneself), planning suicide, attempting suicide and completed suicide [6]. Examination of determinants of suicidal behaviour within this vulnerable age group is critical to its prevention and early intervention.

The need to recognize differences in suicidal behaviour between younger and older adolescents stems from the observed sex-paradox of suicidal behaviour which becomes true at about 15 years of age and indicates that suicidal ideation, planning and attempts are higher among females and ‘completed’ suicide is higher in males [7,8,9]. Thus, older adolescents may have different determinants associated with suicidal behaviours and in many low- and middle- income countries (LMIC) are more likely to be out of school [5, 10]. Additionally, strong evidence exists for different risk indicators for suicidal ideation and attempts by sex with many studies reporting peak suicidal behaviour around 15 years-of-age with the exception of Korean girls, where suicide attempts peak at 13 years of age [11, 12].

Elucidating the pathway towards ‘completed’ suicide among early adolescents is hindered by a low prevalence rate and the heterogeneity of empirical evidence. It is believed that suicidal behaviour is rooted in nonlinear interactions with multiple risk indicators broadly including environmental, biological and psychological factors. Furthermore, many of these factors are bidirectionally impacted by poor access to health services in many LMIC [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

Several groups have explored suicide behaviour in LMIC using data from the Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS). Uddin et al. reported that the African region had the highest prevalence of suicidal ideation (20.4%) and suicide planning (23.7%), while the western Pacific region had the highest prevalence of suicide attempts (20.5%) among adolescents (13–17 years) in 59 LMIC using GSHS data from 2003 to 2015 [21]. This study, however, did not examine any associations with risk or protective factors for suicidal behaviour. A study by McKinnon et al. identified loneliness, alcohol use and bullying with a greater risk ratio among 13–17-year-old adolescents as determinants of suicide ideation and attempt in 32 LMIC using early data from the GSHS [22]. Both studies excluded GSHS high-income countries (HIC) and did not disaggregate early adolescents from late adolescents despite their vastly different suicide mortality rates. Most recently, a study by Koyanagi using GSHS data (2009–2015) found that amongst adolescents (12–15 years) from 48 countries (39 LMIC), being bullied for at least 1 day in the past 30 days was associated with a more than 2-fold higher odds for overall suicide attempt [23]. While this study limited the data to younger adolescents, it severely restricted the available GSHS data by date without explanation and did not include other potential risk indicators.

Robust multi-national data to measure risk and protective factors towards suicide behaviour among early adolescents compared to older adolescents, can provide important evidence leading to targeted support and services for these two vulnerable age groups. Clearly, there is an increased interest in suicidal behaviour research among adolescents living in LMIC, yet previously published studies using GSHS data have not examined differences between early and late adolescents by sex and fail to use all available GSHS datasets.

With the aim of including the most up-to-date GSHS results and a comparative analysis between early and late adolescence, we examine GSHS data (2003–2017) among 13–17-year-old respondents, stratified by age and sex, to determine the association of self-reported risk indicators with suicidal ideation and attempts.

Methods

Data source

We used data from the GSHS implemented in 90 countries. The GSHS is a cross-sectional surveillance survey that aims to collect data among adolescents. The survey is designed to determine the prevalence of internationally comparable health behaviours and risk indicators among adolescents attending school. Country-specific surveys are composed of a select core and core-expanded questions, which can be completed during one school class period. Core questions common to all phases maintained the exact wording in the questions and responses. There were three phases of the GSHS: phase one (2003–2008); phase two (2009–2012) and phase three (2013 to 2019). Detailed methodology of the GSHS is previously reported [24]. As some countries participated in more than one phase of the survey, our final dataset included 118 surveys. Only regional or city data were available for five countries (Zimbabwe, Chile, China, Ecuador and Palestine); all other estimates are nationally representative. Countries were classified according to current the World Bank (WB) Income Groups and the WHO regions. All GSHS surveys obtain approval in their country by a national government agency and an institutional ethics board or committee. Parental consent and participant assent are also obtained. Individual country ranking by sex and age group for mean prevalence estimates for study outcomes by WB Income Group and WHO region are listed in Supplementary Figs. 1–2.

The focus of the current analysis divides adolescents into younger (13–15 years of age) and older (16–17 years of age) groups. These age groups were selected as they are consistent with the publicly reported question response prevalence, which is weighted for the survey design to allow for comparability across countries by accounting for the probability of (a) selection of schools and classrooms, (b) non-responding schools and students and (c) distribution of the population by grade and sex [24].

Outcomes and covariates

One outcome variable – suicidal ideation – was included in all three phases of the survey whereas the second outcome variable - suicide attempt – was only included in phases two and three. Covariates that could potentially explain our outcomes were chosen from core questions using identical wording in at least two phases of the GSHS, from the following modules – mental health, physical activity, protective, violence and unintentional injury (Table 1). All covariates were included in all three phases of the survey except for ‘parental understanding’ which was included in phases two and three.

Statistical analysis

Pooled prevalence estimates with 95% confidence interval (95% CI), were calculated by random-effects meta-analyses using the DerSimonian and Laird inverse variance method by sex for adolescent age groups (13–15 years, 16–17 years) [25]. We determined pooled estimates to be significantly different if the 95% confidence intervals did not overlap.

The level of heterogeneity was assessed using I2 among country surveys; I2 was greater than 80% suggesting substantial heterogeneity among countries for all variables by sex and age groups. To test differences between HIC and LMIC, pooled prevalence estimates with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated by random-effects meta-analyses as outlined above by income group for sex and adolescent age groups (13–15 years, 16–17 years). We found no meaningful differences in pooled estimates according to country income group (Supplementary Figs. 3–6).

Linear multiple regression was used to test if protective or risk indicators were significantly associated with suicide attempts or ideation by sex for each age group. Each estimated β coefficient was interpreted in proper units and tested for significance by performing an analysis of variance (ANOVA). Variables significant at a liberal p-value of less than 0.2 in the bivariate models were considered in the development of a multivariable model using backwards stepwise regression selection. Multivariable models were adjusted for sex, year of survey, WB Income Group and the survey sample size to control for varying populations and contexts. Multicollinearity among selected covariates was assessed using variance inflation factors; a cut-off of three was considered suspect for collinearity. We computed a standardized β coefficient with ordinary least squares regressions. The effect size explained by the model (R2) and the coefficient intervals for the covariates were computed. To assess the significance of the linear regression model, the F-statistic was computed from the ANOVA and interpreted at the α = 0.05 significance level. To validate the model, overfitting was assessed using Bradley Efron’s .632 bootstrap resampling technique. Bootstrap is a non-parametric method that computes the inferential estimate of interest without making assumptions about the distribution [26]. Instead, bootstrap treated the actual sample as the source population and repeatedly drew samples from 63.2% of the actual sample to compute a nearly unbiased estimate of the optimism in the fitted model – accounting for variations caused by the modelling strategy [26].

Two sensitivity analyses were conducted to verify the use of the entire dataset thereby increasing the robustness of the data. The first sensitivity analysis assessed the use of more than one phase per country. Since some countries reported more than one GSHS phase for adolescents aged 13–15 years, all estimates were restricted to only those countries that participated in all survey phases and another for those countries that participated in 2 phases. We found no meaningful differences in mean estimates based on this restricted set of countries allowing for the use of multiple phases datasets per country in the regression analysis (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8). Second, prevalence estimates for 16–17-year-old adolescents were only available for phase two and three and no countries reported more than one phase of the older adolescent data. For this sensitivity analysis, the dataset was limited to the younger age group. Mean estimates were calculated for all variables and stratified according to those with and without the older age group. No meaningful differences were observed, allowing for the entire dataset thereby increasing the robustness of the data (Supplementary Fig. 9). We considered p-values less than 0.05 as statistically significant. The random-effects meta-analyses were conducted using RevMan 5.3 all other analysis was executed using R.3.5.1 statistical software.

Results

Income-level analysis

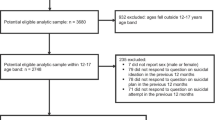

This analysis represents 310,055 (51.7% female) students aged 13–15 years and 87,244 (49.6% female) aged 16–17 years. Of the 118 surveys used in the analysis, 26 (22.0%) were from HIC, 42 (35.6%) were from upper-middle-income countries, 34 (28.8%) from lower-middle-income countries and 13 (11.0%) from low-income countries, 3 (2.5%) came from unclassified countries. Regionally, 19 (16.1%) were from the African Region, 38 (32.2%) were from the Americas, 19 (16.1%) from Eastern Mediterranean, 2 (1.7%) from European Region, 14 (11.9%) from South-East Asia and 26 (22.0%) from the Western Pacific Region.

Age and sex - level analysis

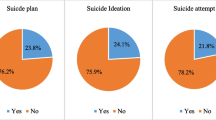

Few differences in the pooled prevalence’s were significant. Here, we highlight some of the trends from Fig. 1. The pooled prevalence of suicide ideation was lower for boys than girls, with little difference between age groups of the same sex. Conversely, the pooled prevalence of suicide attempts did not differ greatly by sex or age group. The pooled prevalence of parental understanding and having no close friends were similar by age group and sex. Physical activity, attending PE class, being in a physical fight, having a serious injury and begin bullied decreased with age. Additionally, physical activity, being in a physical fight, and having a serious injury were significantly less prevalent among girls.

Country-level analysis

Suicide ideation was the lowest for girls and boys 13–15 years living in Myanmar (survey year 2007) at 0.8 ± 0.5% and 0.7 ± 0.7% and for 16–17 years girls and boys living in Laos (survey year 2015) at 1.6% (95% CI:1.7–3.9) and 3.9% (95% CI: 2.6–6.8) respectively. The highest prevalence of suicide ideation among boys 13–15 years was in Samoa (survey year 2011) at 37.1% (95% CI: 33.8–40.5) among boys 16–17 was 22.8% (95% CI: 18.0–28.4) in Liberia (survey year 2017). In Kiribati (survey year 2011) girls, 13–15 years at 36.2% (95% CI: 31.9–41.7) and in Wallis and Futuna (survey year 2015) girls 16–17 at 35.9% (95% CI: 29.8–42.5) had the highest prevalence for suicide ideation.

The lowest prevalence for reported suicide attempts was among 13–15-year-olds living in Suriname (survey year 2016) at 4.2% (95% CI: 2.1–8.2) for boys and living in Indonesia (2015) (3.6% (95% CI: 2.9–4.5) for girls. Among 16–17-year-old adolescents the lowest prevalence for girls was among those living in Indonesia (survey year 2015) at 2.7% (95% CI: 1.7–4.1) and for boys was among those living in Laos (survey year 2015) at 3.8% (95% CI: 2.2–6.3). The highest prevalence of suicide attempts among 13–15-year-old boys and girls was for those living in Samoa (survey year 2011) at 67.2% (95% CI: 59.2–74.3) and (53.7% (95% CI: 45.1–62.1) respectively. Among 16–17-year-old boys, the highest prevalence for suicide attempts was 33.6% (95% CI: 28.3–39.4) for those living in Liberia (survey year 2017) and girls living in Ghana (survey year 2012) at 35.2% (95% CI: 24.3–47.9).

Factors associated with suicidal behaviour

The bivariate and multivariable assessments of factors related to suicidal ideation for those 13–15 years are presented in Table 2. Factors associated with suicidal ideation varied by sex. For girls, being bullied (β = 0.4, p < 0.001) remained a significant predictor in the multivariable suicidal ideation model, where one covariate explained 23% of the variance (R2 = 0.23, F (5,107) = 6.3, p < 0.001). Whereas for boys, having a serious injury (β =0.3, p < 0.001), no close friends (β =0.3, p < 0.001) and being in a physical fight (β =0.3, p < 0.01) remained statistically significant in the multivariable suicidal ideation model, where these three factors explained 52% of the variance in suicidal ideation (R2 = 0.5, F (7,103) =16.8, p < 0.001). Multivariable regression results detailing the covariates that significantly associated with suicide attempt for those 13–15 years are presented in Table 3. In sex-stratified analyses, being bullied (β = 0.3, p < 0.01) and having had a serious injury (β = 0.4, p < 0.001) remained a significant factor for girls in the multivariable suicide attempt model, where these two covariates explained 52% of the variance (R2 = 0.5, F (6, 69) =12.3, p < 0.001). Whereas for boys, being seriously injured (β =0.4, p < 0.001), being bullied (β =0.3, p < 0.001) and having no friends (β =0.3, p < 0.001) all remained significant predictors in the multivariable suicide attempt model, where these three covariates explained 69%of the variance (R2 = 0.7, F (7, 67) =20.8, p < 0.001).

The bivariate and multivariable assessments of factors related to suicidal ideation for those 16–17 years are presented in Table 4. Factors associated with suicidal ideation varied by sex. For girls, only having no close friends (β = 0.4, p < 0.01) remained a significant predictor in the multivariable suicidal ideation model, where one covariate explained 32% of the variance (R2 = 0.3, F (5, 38) =3.6, p = 0.01). Whereas for boys, being in a physical fight (β =0.6, p < 0.001) and having no close friends (β =0.5, p < 0.001) remained statistically significant in the multivariable suicidal ideation model, where these two factors explained 55%of the variance in suicidal ideation (R2 = 0.5, F (6, 38) =7.7, p < 0.001). Multivariable regression results detailing the covariates that significantly associated with suicide attempt for those 16–17 years are presented in Table 5. In sex-stratified analyses, being bullied (β = 0.5, p < 0.001) and having no close friends (β = 0.4, p < 0.001) remained a significant factor for girls in the multivariable suicide attempt model, where these two covariates explained 62% of the variance (R2 = 0.6, F (6, 36) =9.9, p < 0.001). Whereas for boys, being seriously injured (β =0.6, p < 0.001), having no close friends (β =0.4, p < 0.01) a remained significant predictor in the multivariable suicide attempt model, where these three covariates explained 56%of the variance (R2 = 0.6, F (6, 36) =7.7, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Across all countries included in this analysis, the prevalence of suicidal ideation among adolescents aged 13–17 years is strikingly higher among girls than boys with very little differences between younger and older adolescents. However, suicide attempt did not differ by age group or sex. From our multivariable model, significant indicators associated with suicidal ideation or attempt included being bullied, having no close friends, being in a physical fight and/or a having had a serious injury. Not surprisingly, indicators related to parental connection or country income status failed to be significant, whereas those related to peer connection or isolation were significantly associated with suicide ideation and/or attempts. The convergence of bullying, aggression (fighting) and no friends reflects a problem in social relationships during the entire phase of adolescence, with little difference between HIC and LMIC.

Over the last 15 years, GSHS has collected information on the health behaviours in adolescents. Comparable tools, such as the Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC), Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) and Korean Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey (KYRBS) have generated knowledge on suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in adolescents in predominantly developed countries [27,28,29]. The sex paradox observed in large epidemiological surveys conducted in high-income countries, including the YRBSS and KYRBS, where adolescent females more often plan and attempt suicide, while adolescent males more often complete suicide was not apparent in the GSHS data [28, 29].

Respondents of the Samoan GSHS (2011) experienced a disproportionately higher burden of suicidal ideation and attempt compared to other countries, particularly among boys. (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). This finding is consistent with historical data on youth suicide in Samoa. Countries in the Pacific Region, including Samoa, experienced epidemic youth suicide rates between 1960 to 1995 with a peak in 1980 [30]. High suicide rates in Samoa continued until 2013 despite significant investments in prevention programs [31]. More recent estimates from Samoa (2016) show a 20–40% decrease of adult suicide mortality attributed largely to the success in a ban on lethal pesticides like paraquat [4, 32,33,34,35]. Administering another GSHS in Samoa would be of great use to determine the possibility of similar success among adolescents.

Within our study, after adjusting for covariates, bullying remains a significant risk indicator associated with suicide attempt in both males and females. Our findings are consistent with the HBSC study, which found adolescents from Israel, Lithuania and Luxembourg who experienced cyberbullying and school bullying, had a significantly higher risk associated with suicidal ideations, plans and attempts [16]. From a LMIC perspective, the Young Lives study analyzed longitudinal predictors and associations of bullying in nearly 12,000 adolescents, over a 15-year period in Peru, Ethiopia, India and Vietnam through mixed methods. Their results suggest that bullying is corrosive and associated with long-term negative effects on self-esteem, self-efficacy, peer and parental relations [36]. The authors noted that indirect bullying (i.e. humiliation and social exclusion) was the most prevalent type of bullying experienced by age 15, in three of four countries ranging from 15% in Ethiopia to 28% in India. Our findings are also consistent with two recent systematic reviews which found that bullying perpetration and victimization via traditional (face-to-face) or cyberbullying were associated with deliberate self-harm in adolescents [37, 38].

Furthermore, our findings indicate a vulnerability to bullying during early adolescence suggesting early, preventive and context-appropriate interventions may be necessary to impact suicide behaviours and to help resolve mental health issues. Particularly, the results from GSHS corroborate this need in LMIC [39]. In fact, a previous systematic review and meta-analysis reviewed 99 studies on youth suicide interventions, where only 2% were conducted in a LMIC. Several challenges exist in these settings, including the paucity of mental health services and personnel, as well as, poor monitoring and evaluation systems [40]. Though school-based interventions have been effective in promoting mental health through education, there is potential to miss vulnerable adolescents, as dropout rates are higher in LMIC, especially in females, as compared to HIC [39]. Moreover, as bullying and cyberbullying have become a systemic public health issue, innovative approaches that transcend the school, including the integration of community, parental and mobile health interventions, are necessary to intervene early and prevent social marginalization and victimization. Given our findings, future research should focus on the generalizability of HIC bullying prevention and intervention models towards LMIC, as well as, understanding the temporality and progression of suicide risk indicators to ideation and suicide attempts in adolescents.

Our findings have important implications for policy and programmatic action. Notably, that adolescents are vulnerable humans who are susceptible to both positive and negative influences of environment, is evident from our work. Intervening with these individuals at critical points of entry, such as in schools, in families and within communities, is critical to bringing about sustainable change. To this end, governments should prioritize school-based intervention models to target both in-person and cyber bullying. Peer-to-peer support or self-help groups coordinated by teachers and administrators may be one approach to consider. Encouraging social activities that focus on building relationships and fostering a sense of trust, may be ways that schools and communities can prevent bullying and help adolescents build close friendships. Government’s focus on identifying and providing physical, emotional and social support to youth who have experienced injuries is important. For instance, through health walk-in clinics or through youth networks, would yield notable dividends on health and survival of this population. Widespread education campaigns on mental health and well-being for parents, teachers, public service offices and communities will be invaluable to building a supportive environment for at-risk youth.

Several limitations of this work should be considered. The GSHS’s cross-sectional design precludes temporal and causal inference. As the survey is school-based, information on important national, community and household indicators factors were missing, such as socioeconomic status, food security, family risk and protective factors, cultural and religious factors or national political climate. Additionally, in some LMIC where school attendance is low (especially among girls), the data may not be nationally representative. The GSHS did not ask specific questions on previous childhood abuse, behaviour, family history, previous mental illness or questions related to severity of depression which are also known risk indicators for poor mental health. Such data should be evaluated for inclusion in future phases of the GSHS. The sensitive nature of questions, self-reporting may have introduced bias due to under- or over-reporting on certain questions. Specific questions related to serious injury and bullying included in our analyses are limited in that they potentially under- or over- capture true responses. More specifically, ‘serious injury’ captures injuries from both intentional (violence, self-harm) and unintentional (road accidents) causes, while bullying may have only captured classical bullying (face-to-face), as opposed to the inclusion of cyberbullying. Sexual orientation may be a hidden risk indicator since it is not available in the current GSHS data. A recent systematic review reported higher rates of depression among young lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning (LGBTQ) and LGBTQ-factors were associated with suicide risk [41, 42]. This may help explain some of the findings regarding bullying, injuries, etc. Since our analyses were ecological (i.e. using country-year data points), caution should be applied when making individual-level inferences. Lastly, since the GSHS design is intended to capture a representative sample of younger adolescents, prevalence estimates of older adolescents (16–17 years) may not be representative. While our results should be interpreted in light of these limitations, this pooled analysis represents a large number of participants in predominately LMIC, where much data on adolescents are lacking. Strengths of this analysis lie with the use of a validated tool administered in a large number of countries over approximately 15 years.

Conclusion

Mental health has been recognized as an important priority in several global agendas, including Goal 3 of the Sustainable Development Goals and the WHO Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020. Understanding the distribution and determinants of mental health-related conditions in the leaders of tomorrow – adolescents – is a critical step towards these goals. Programs should focus on improving social relationships throughout adolescence by sex, with specific themed interventions for younger and older adolescents. Our work should be used to continue and expand on the mental health dialogue and action worldwide.

Availability of data and materials

Data are publicly available. The Global Student-based School Health Survey data that support the findings of this study are available in the CDC-GSHS repository at https://www.cdc.gov/gshs/countries/index.htm

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control

- GBD:

-

Global Burden of Disease

- GSHS:

-

Global School-based Student Health Survey

- HBSC:

-

Health Behavior in School-aged Children

- HIC:

-

High-Income Countries

- KYRBS:

-

Korean Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey

- LMIC:

-

Low and middle-income countries

- WB:

-

World Bank

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- YRBSS:

-

Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System

References

United Nations. The sustainable development goals report. USA: United Nation; 2017.

World Health Organization: LIVE LIFE: Preventing Suicide. In. Geneva: Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, World Health Organization; 2018.

Kolves K, De Leo D. Suicide rates in children aged 10-14 years worldwide: changes in the past two decades. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(4):283–5.

Naghavi M. Global burden of disease self-harm C: global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. BMJ. 2019;364:l94.

Miranda-Mendizabal A, Castellví P, Parés-Badell O, Alayo I, Almenara J, Alonso I, Blasco MJ, Cebrià A, Gabilondo A, Gili M, et al. Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Int J Public Health. 2019;64(2):265–83.

WHO. Preventing suicide. Geneva: A global imperative; 2014. p. 92.

Borges G, Benjet C, Orozco R, Medina-Mora ME. The growth of suicide ideation, plan and attempt among young adults in the Mexico City metropolitan area. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2017;26(6):635–43.

Ibrahim N, Amit N, Che Din N, Ong HC. Gender differences and psychological factors associated with suicidal ideation among youth in Malaysia. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2017;10:129–35.

Canetto SS, Sakinofsky I. The gender paradox in suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1998;28(1):1–23.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). New Methodology Shows that 258 Million Children, Adolescents and Youth Are Out of School, vol. 56: UIS; 2019.

Kang E-H, Hyun MK, Choi SM, Kim J-M, Kim G-M, Woo J-M. Twelve-month prevalence and predictors of self-reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among Korean adolescents in a web-based nationwide survey. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49(1):47–53.

Husky MM, Olfson M, He JP, Nock MK, Swanson SA, Merikangas KR. Twelve-month suicidal symptoms and use of services among adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Psychiatric Serv (Washington, DC). 2012;63(10):989–96.

Vancampfort D, Hallgren M, Firth J, Rosenbaum S, Schuch FB, Mugisha J, Probst M, Van Damme T, Carvalho AF, Stubbs B. Physical activity and suicidal ideation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2018;225:438–48.

Barber B. Regulation, connection, and psychological autonomy: Evidence from the Cross-National Adolescent Project (C-NAP). In: 2002: WHO-sponsored meeting Regulation as a Concept and Construct for Adolescent Health and Development. Geneva: WHO Headquarters; 2002.

Sosin DM, Koepsell TD, Rivara FP, Mercy JA. Fighting as a marker for multiple problem behaviors in adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1995;16(3):209–15.

Zaborskis A, Ilionsky G, Tesler R, Heinz A. The association between cyberbullying, school bullying, and suicidality among adolescents. Crisis. 2018.

Grandclerc S, De Labrouhe D, Spodenkiewicz M, Lachal J, Moro MR. Relations between nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior in adolescence: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153760.

Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE Jr. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117(2):575–600.

Jackson H, Nuttall RL. Risk for preadolescent suicidal behavior: An ecological model. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2001;18(3):189–203.

Cha CB, Franz PJ, MG E, Glenn CR, Kleiman EM, Nock MK. Annual research review: suicide among youth - epidemiology, (potential) etiology, and treatment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2018;59(4):460–82.

Uddin R, Burton NW, Maple M, Khan SR, Khan A. Suicidal ideation, suicide planning, and suicide attempts among adolescents in 59 low-income and middle-income countries: a population-based study. Lancet Child Adolescent Health. 2019;3(4):223–33.

McKinnon B, Gariepy G, Sentenac M, Elgar FJ. Adolescent suicidal behaviours in 32 low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(5):340–350F.

Koyanagi A, Oh H, Carvalho AF, Smith L, Haro JM, Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, DeVylder JE. Bullying victimization and suicide attempt among adolescents aged 12-15 years from 48 countries. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(9):907–18 e904.

WHO CDC. Global school-based student health survey: data User's guide. USA: CDC; 2013.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88.

Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An introduction to the bootstrap: CRC press; 1994.

Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) [http://www.hbsc.org/about/index.html].

Park S, Jang H. Correlations between suicide rates and the prevalence of suicide risk factors among Korean adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2018;261:143–7.

Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, Lowry R, Chyen D, Whittle L, Thornton J, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(8):1–114.

Booth H. Gender, power and social change: youth suicide among Fiji Indians and Western Samoans. J Polynesian Soc. 1999;108(1):39–68.

Tiatia-Seath S, Lay Yee R, Von Randow M. Suicide mortality among Pacific peoples in New Zealand, 1996–2013; 2017.

Bourke T: Suicide in Samoa. Pacific health dialog 2001, 8(1):213–219.

Gunnell D, Knipe D, Chang SS, Pearson M, Konradsen F, Lee WJ, Eddleston M. Prevention of suicide with regulations aimed at restricting access to highly hazardous pesticides: a systematic review of the international evidence. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(10):E1026–37.

Bowles J. Suicide in Western Samoa: an example of a suicide prevention program in a developing country. Brill: Preventive strategies on suicide Leiden; 1995. p. 173–206.

Stewart-Withers RR, O’Brien AP. Suicide prevention and social capital: a Samoan perspective. Health Sociol Rev. 2006;15(2):209–20.

Pells K, Portela MO, Revollo PE. Experiences of peer bullying among adolescents and associated effects on young adult outcomes: longitudinal evidence from Ethiopia. India, Peru and Viet Nam: UNICEF Office of Research–Innocenti; 2016.

Heerde JA, Hemphill SA. Are bullying perpetration and victimization associated with adolescent deliberate self-harm? A Meta-Analysis. Arch Suicide Res. 2019;23(3):353–81.

van Geel M, Vedder P, Tanilon J. Relationship between peer victimization, cyberbullying, and suicide in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(5):435–42.

Lund C, De Silva M, Plagerson S, Cooper S, Chisholm D, Das J, Knapp M, Patel V. Poverty and mental disorders: breaking the cycle in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet (London, England). 2011;378(9801):1502–14.

Robinson J, Bailey E, Witt K, Stefanac N, Milner A, Currier D, Pirkis J, Condron P, Hetrick S. What works in youth suicide prevention? A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2018;4-5:52–91.

Gnan GH, Rahman Q, Ussher G, Baker D, West E, Rimes KA. General and LGBTQ-specific factors associated with mental health and suicide risk among LGBTQ students. J Youth Stud. 2019:1–16.

Lucassen MFG, Stasiak K, Samra R, Frampton CMA, Merry SN. Sexual minority youth and depressive symptoms or depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51(8):774–87.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Zahra Hussain and Argie Stephen Gingoyon for their assistance with data extraction.

Funding

SCC is supported by SickKids Restracomp doctoral award; SCC and CZ are supported by the Cundill Centre for Child and Youth Depression, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. PS is supported by the Patsy and Jamie Anderson Chair in Child and Youth Mental Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SCC conceptualized the research question and developed the analysis plan jointly with BC, and NA. SCC, NA, CZ, and BC analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. CZ contributed to data extraction. SCC, NA, CZ, BC, PS, and ZAB read, and contributed to revising the manuscript. ZAB and PS provided senior supervision for the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

As all data is publicly available, ethics approval for this analysis was not required for this analysis.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 Supplementary Fig. 1

. Country Prevalence of Students who Reported One or More Suicide Attempts in the Past 12 Months by WB Income Group by WHO Region. Supplementary Fig. 2. Country Prevalence of Reported Suicide Ideation in the Past 12 Months by WB Income Group by WHO Region. Supplementary Fig. 3. Pooled Prevalence Estimates per GSHS Question for HIC and LMIC, boys 13–15 Years. Supplementary Fig. 4. Pooled Prevalence Estimates per GSHS Question for HIC and LMIC, boys 16–17 Years. Supplementary Fig. 5. Pooled Prevalence Estimates per GSHS Question for HIC and LMIC, girls 13–15 Years. Supplementary Fig. 6. Pooled Prevalence Estimates per GSHS Question for HIC and LMIC, girls 16-17 Years. Supplementary Fig. 72. Sensitivity Analysis. Mean Prevalence Estimates per GSHS Question, per phase, boys 13–15 Years. Supplementary Fig. 8. Sensitivity Analysis. Mean Prevalence Estimates per GSHS Question, per phase, girls 13–15 Years.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Campisi, S.C., Carducci, B., Akseer, N. et al. Suicidal behaviours among adolescents from 90 countries: a pooled analysis of the global school-based student health survey. BMC Public Health 20, 1102 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09209-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09209-z