Abstract

Background

Several Asian countries have implemented pictorial health warnings on cigarette packs as suggested by the World Health Organization with various policies based on countries’ systems. The study is aimed to analyse multiple research studies on the perceived effectiveness of Pictorial Health Warnings as a deterrent to smoking intention and as a stimulant of smoking behaviour in smokers and non-smokers in Asian countries.

Method

Peer-reviewed articles were identified through multiple science databases indexed by Scopus, MEDLINE or PubMed. The review was limited to articles that reported original research findings, were conducted in Asian countries and were available for review by January 2010. A PRISMA Flow diagram was used to identify the articles through the process of data screening and extractions.

Result

A total of 14 original articles which met the criteria were included in the review, consisting of 12 quantitative studies and 2 studies with both quantitative and qualitative methods from 17 jurisdictions. The reviewed studies found that pictorial health warnings were associated with a greater perception of salience (reading and noticing the warning), emotional effects, and cognitive increase. Additionally, in the reviewed studies, pictorial health warnings were perceived as more effective in deterring smoking initiation and encouraging smoking cessation than text-only warnings. Several studies also evaluated the effectiveness of a new pictorial warning compared with the old one. However, the relevance of refreshing the pictures of pictorial health warnings and the length of the effective period of the implementation of pictorial health warnings were less frequently studied.

Conclusion

Pictorial health warnings perceived as more effective in deterring smoking initiation among non-smokers and as well as in stimulating smoking cessation among smokers. Future studies on pictorial health warnings should study the relevance of changing or refreshing pictorial health warning on cigarette packages in a period of time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Asia, with its varied political systems and vast population, has the highest number of tobacco consumers and is the main target of transnational tobacco industries, especially China, India, and Indonesia [1]. To address tobacco issue in Asia, the World Health Organization (WHO) has assisted the member states in this continent to implement WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) which came into force in 2005. FCTC is global standards and guidelines for tobacco policy among WHO members which successfully improved tobacco control policy in 120 out of 174 countries by 2011 [2]. The WHO’s FCTC is the first global tobacco-control treaty that encourages ratifying countries to develop and implement tobacco control policies in their own countries, regulating about tobacco advertising, tobacco tax and price, smoke-free area, and health warning message on tobacco packages [3].

Graphic health warnings, which make the potential of smoking to cause diseases more real to smokers, both can improve public knowledge, and work to encourage cessation through the generation of concern stimulated by the emotionally charged messages [4]. The use of pictorial warnings is of special relevance in countries with low literacy rate [5]. A study conducted by Scollo and Winstanley [6] found that smokers who smoked 20 cigarettes per day would be exposed to the health warnings around 7000 times each year.

Studies in the USA found that recognition of warnings in pictorial health warnings was higher than those in text-only warning. Additionally, the lung cancer warning discouraged adolescent non-smokers from wanting to smoke [7, 8]. Pictorial warnings have been found to be effective in deterring smoking, especially among the young [9]. However, Li, Chan, and Lam [10], who conducted a study on smoking behaviour among Hong Kong Chinese women, found that current, ex- and never smokers thought that smoking cessation advertisements were less strong than anti-drug advertisements. Nevertheless, current and ex-smokers in the study were aware of pictorial health warnings on cigarette packs which showed varying degrees of horror and disgust.

However, evidence found the large health warnings as it has been documented that larger health warnings covering more of the front of the pack are more effective than smaller warnings [11]. It is also supported by psychological theories which argued the better recall of larger warning [12]. Moreover, refreshing the pictures on pictorial health warnings regularly in a period of time was known to help to sustain the effects on smokers [13]. Thus, this study is aimed to analyse multiple research studies conducted in Asian countries to describe the perceived effectiveness of Pictorial Health Warning (PHWs) in deterring smoking initiation among non-smokers and stimulating smoking cessation among smokers.

Methods

Data sources

Peer-reviewed articles were identified through multiple science databases: Sciencedirect, ProQuest, Oxford Journals, SpryngerLink, SAGE and Scopus which are indexed to Scopus, Medline or PubMed. We also included Google Scholar as the source of scientific papers to search for more articles that might not be published in the indexed journals. Electronic searches were conducted to identify relevant literature. The following keywords were used to identify relevant articles: (“pictorial warning”; “graphic warning”; “health warning”) with at least one of the following terms: smoking, tobacco, cigarette, product, package, and pack. All articles appearing in the search results were listed.

The review was limited to articles that reported original research findings and were published from January 2007 to Jathe nuary 2017. Studies which do not content aspects of warning, packaging and labelling regulation were excluded, as well as studies conducted in other Asian countries. Due to the diversity of research methods in this domain, the reviewer did not restrict studies to a particular design; however, each of the articles were reviewed for the following methodological criteria: (1) objectives and/or research questions were clearly explained, (2) sample and/or study population are described, (3) data collection method is consistent, (4) key measurements are adequate and valid, (5) results are clearly defined and measured (6) analysis of findings are clear and appropriate.

Data extraction

In conducting the data extraction, we firstly excluded articles that did not include Asian settings and/or did not sufficiently represent Asian countries as their study locations. A total of 141 articles were identified by titles which resulted in 14 articles excluded due to duplications. The 127 articles presenting empirical data were identified by titles and abstracts, 87 were excluded due to poor aspects of warning, packaging, and labelling. The 40 articles were identified by abstracts and methods which resulted in excluding 26 more articles due to insufficient methodological information. The 14 original articles included in the review consisted of 12 quantitative studies and 2 studies with both quantitative and qualitative components. The strategy of data extraction and identification used a PRISMA flow diagram [14].

Results

After removing duplicates and ineligible articles, 14 studies met the inclusion criteria based on study locations, appropriate variables measured and sufficient study methods. A PRISMA diagram flow can be seen in Fig. 1. The most common reasons for exclusion of candidate articles were because no effect of pictorial warnings on smoking behaviour evaluated, or country of study. A summary of each study is available in online supplementary Table 1. Research articles came from the following jurisdictions: Malaysia (n = 3), Thailand (n = 2), India (n = 2), China (n = 3), Lao PDR (n = 1), Qatar (n = 1), Bangladesh (n = 1), Pakistan (n = 1), Jordan (n = 1), Turkey (n = 1), Indonesia (n = 1). Several articles included data collected in multiple countries. However, these articles were counted as a single study but recorded in multiple jurisdictions.

Online supplementary and Operationalisations of the studies

No study met the criteria for inclusion prior to 2010. Meanwhile, the most recent study that was included in this study was published in 2016. During that period, the number of studies measuring the effectiveness of pictorial health warnings in Asian countries seems to fluctuate. There are two studies published in 2010, two studies published in 2011, four studies published in 2013, one study published in 2014, four studies published in 2015, and one study published in 2016. Most studies were published in credible international journals indexed by Scopus, MEDLINE, PubMed, ProQuest, and EBSCO. There was only one study published in the ResearchGate site. The online supplementary of the reviewed studies can be seen in Table 1.

Twelve studies used a quantitative method based upon the designs of cross-sectional (n = 5), cohort (n = 2), survey (n = 2), case-control (n = 1), or experiment (n = 2). The rest of the studies (n = 2) used a mix between quantitative and qualitative methods by conducting both a cross-sectional study and a focus group discussion. Regarding the number of the study population, the smallest sample was obtained by Wu et al [15]. who interviewed 202 people derived from a multistage-random sampling. Additionally, in Pakistan, the effectiveness of graphic health warning was measured among 388 high school students [16]. Meanwhile, the study in LAO PDR evaluated the implementation of pictorial health warnings both in average citizens and policy makers [17]. On the other hand, the study by Elton-Marhsall et al. [18] examined a big study population with 6513 adult smokers in China and 2883 adult smokers in Malaysia. Additionally, the study by Mutti et al. [19] had the highest response rate by 98.94% among 2061 respondents. Moreover, all studies performed univariate and bivariate analyses. However, only five studies were found to conduct a multivariate analysis. The operationalisation and statistical analysis of the reviewed studies can be seen in Table 2.

Demographic characteristics and smoking behaviour in the studies

The studies obtained data from a variety of demographic characteristics of respondents, including age, sex, occupation, income, level of educations, ethnicity, and nationality. Three studies were conducted among adults (aged more than 18 years old), one study was carried out among teenagers (ranged from 15 to 18 years old), three studies were conducted among youths and young adults (ranged from 15 to 26 years old) and the rest five studies were carried out among both youths and adults (aged < 18 years old and ≥ 18 years old). Twelve studies obtained the data from both male and female respondents, while only one study conducted among male respondents only and the rest did not mention any specific gender characteristic.

Regarding study locations, three studies obtain the data in urban and rural areas; one study obtained the data in urban, semi-urban and rural areas, six studies gathered the data in urban areas only, while the rest of the studies did not specify it. Three studies included ethnic groups in their respondents’ characteristics which were classified as han-chinese and non-han-chinese groups in China and the majority and minority in Thailand and Malaysia. Another study in Qatar also classified their respondents based on their nationality which was divided as Qatari and non-qatari [20]. One study also obtained information about respondents’ medical conditions. Additionally, two studies in Qatar and China also collected information about respondents’ marital status [18, 20]. Additionally, most of the studies classified their respondents based on their education levels which mostly were divided into four groups: illiterate, low (up to middle school), high (up to high school), and graduate (diploma or higher). Five studies obtained information about respondent’s occupations. Moreover, eight studies classified respondents’ incomes which were mostly divided into three groups: low, moderate and high.

Smoking behaviour

The data in the studies reviewed were obtained from respondents with different smoking behaviours. Eight studies examine both smokers and non-smokers, while six studies examine smokers only. Adult smokers were classified as follow: non-daily smokers, daily smokers, weekly smokers, smokeless tobacco users, and mixed between smokeless and smoked tobacco users. While youth smokers were classified as follow: daily smokers, occasional smokers, smokeless tobacco users, and mixed users. On the other hand, non-smokers were mostly classified into never-smoker, former smoker, susceptible and non-susceptible (for youth). The majority of the studies found that the percentages of male smokers were higher than that of smoking women. It is relatively a result of the higher number of male respondents than female respondents in the studies.

Compared with China and Thailand, smokers in Malaysia smoked fewer cigarettes with the average of 0–10 cigarettes per day [13, 18]. However, another study found that the majority of smokers in Malaysia smoked 11–20 cigarettes per day (48.6% in the control group and 55.1% in the intervention group) [4]. Moreover, most of the smokers in China consumed 11–20 cigarettes per day [13, 18], while in Indonesia the average of cigarettes smoked per day was 15 [21]. Studies in China showed a different variation of time to the first cigarette after waking up on a day. A study by Elton-Marshall [18] found that they smoked their first cigarette in less than 5 min after waking up while another study by Fong [22] found that they started in between 5 to 30 min. Similarly, in Malaysia, Elton-Marshall [18] found that the smokers smoked their first cigarette in 6 to 30 min after waking up, while Fathelarahman [4] found that they started after 60 min they woke up in the morning both in control and intervention groups. The study in Indonesia shows that most of the adult smokers started their first smoke after 60 min as they woke up in the morning [21]. Further demographic characteristics and smoking behaviours measured in the reviewed studies can be seen in Table 3.

Reaction to pictorial warnings

Generally, respondent’s reactions to pictorial warnings in the reviewed articles can be classified into three categories: salience (reading, looking at or noticing the warning), emotional reaction, and cognitive reaction as shown in Table 4. A study in Jordan found that all proposed pictorial warnings in the study had greater proportions of perception of salience among both non-smokers and smokers compared with the currently-implemented pictorial warning which was less shocking and has a smaller size [23]. In Malaysia, following the implementation of new graphic health warning, the study by Fathelrahman, et al. [4] found that the association between the pictorial warnings and the increase in avoiding looking at or thinking about the label was significant in both control and intervention groups (ps = 0.003 and < 0.001 respectively). However, the increase in the intervention group after being exposed to the pictorial warning was much higher than that in the control group after being exposed to the text-only warning (40.6% and 21.4% increases).

In line with that, in Malaysia, Elton-Marshall et al. [18] also found significant in the change in noticing, reading and avoiding looking at/thinking of the label following the new pictorial warning compared with China text-only warning (ps = 0.02, 0.04, 0.02 respectively). Prior to the new pictorial warning, Malaysia had implemented text-only warning until January 2009 which was not changed over a period of time [4, 13]. Meanwhile, here was no significant change in noticing, reading and avoiding looking at the label over the period of the implementation of text-only warning in Malaysia [13]. On the other hand, the study found significant in avoiding looking at the label following the new graphic health warning in Thailand compared with their Malaysian counterparts (p value < 0.01). The same pattern also applied to the change in noticing and reading the label in the comparison between Thai pictorial warning and Malaysian text-only warning (ps < 0.001 and < 0.05) [13]. On the other hand, In India, noticing the pictorial warning on tobacco product was not associated with smoking behaviour [24].

Several studies also measured the emotional effects of pictorial warning vs. text-only warning or new pictorial warning vs. the old ones. The study conducted in young Jordanian adult found that the picture of a coffin elicited more fear in both smokers and non-smokers compared with the current pictorial warning which showed a diseased lung (p value < 0.001) [23]. Similarly, the study in Turkish youth showed that fear and disgust were evoked by the exposure to pictorial warning label among smokers and non-smokers [25]. The fear elicitation effect was also shown among Qatari Adult after being exposed to the pictorial warning [20].

In the reviewed studies, the cognitive effects such as the gain of knowledge or information and thinking of harm of smoking had been found significantly associated with the exposure to the pictorial warnings. The study in young Jordanian adult yielded a significantly greater proportion of gained information after being exposed to a child using inhaler compared with the current-lung-diseased-warning in both smokers and non-smokers (ps = 0.05 and < 0.001 respectively) [23]. Similarly, Malaysian-adult smokers thought of harm (p value = 0.004) and showed the change of knowledge (p value = < 0.001) after being exposed to the pictorial warning [16]. In line with that, a study in Qatari adult yielded gained information after the exposure to pictorial warning vs. exposure to text only warning (0.03). However, the thought of health risk was not found significantly associated with the exposure of pictorial warning nor significantly different between the change of text-only warning to the pictorial warning in Malaysia and the change of the old text-only warning to the new one in China (p value = 0.13) [13, 18, 23].

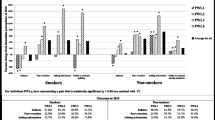

Perceived effectiveness of PHW as a deterrent to smoking intention

In the reviewed articles, the perceived effectiveness of pictorial warning as a deterrent of smoking intention was mostly assessed in both smokers and non-smokers. In non-smokers, the perceived effects of pictorial warnings were evaluated in deterring smoking initiation among youth. Meanwhile, in smokers, the perceived effects of pictorial warnings were examined in restraining them to start smoking. Aumaneekul et al. [26] compared pictorial warning and the plain packaging which resulted in greater intention not to smoke in non-smokers and ex-smokers after exposure to plain packaging compared with the current smokers (p value < 0.05). Similarly, in Indonesia, the level of confidence to avoid smoking in the future in youth non-smokers was found significantly different between before and after exposure to pictorial warning (p value < 0.05) [21]. Moreover, a study in India and Bangladesh also showed that the perceived effectiveness of graphic warning was rated higher than the symbolic and testimonial warnings (p value < 0.01) [19]. In contrary, the study in Jordan did not find any significant difference between the proposed pictorial warnings compared with the current warning [21]. In line with that, Tugrul et al. [25] did not find any differences between female and male respondents in perceiving the effectiveness of pictorial warning in motivating not to smoke among non-smokers and among those who ever consider smoking (ps = 0.561 and 0.424 respectively).

Perceived effectiveness of PHW as a stimulant of smoking cessation

The study by Hawari et al. [23] yielded a significant difference between female and male smokers in perceiving the effectiveness of pictorial warning in motivating not to start smoking and to quit smoking (ps = 0.019 and 0.002, respectively). The perception was significantly indicated by fear rather than disgust [23]. In Indonesia, the study by Dien et al. [21] revealed that the differences of the level of confidence to stop smoking in the future between before and after the exposure to pictorial warnings were found significant with p value < 0.001 in both youth and adult smokers. Similarly, Mutti et al. [19] found that the perceived effectiveness of graphic warning on smoking cessation compared with symbolic and testimonial warning was significantly different (ps = < 0.001).

In Malaysia, fathelarahman et al. [4] examine the perceived effectiveness of pictorial warnings in three different variables: think to quit smoking, no interest in quitting smoking; and interested in quitting smoking within the next month. All of the three variables were found significantly different between before and after exposure to pictorial warnings [4]. Fong et al. compared the old Chinese text-only warning with the new one and with several different types of warnings from different countries. The study found that pictorial warnings were rated higher in motivating to quit smoking compared to text-only warning (p value < 0.001). Similarly, Yong et al. [13] found that there were significant differences between the likely to quit smoking in wave 1 and wave 3 (after the implementation of new warning) with p values < 0.001 in Thailand and < 0.05 in Malaysia. Moreover, the study yielded the significant differences between the avoidance of cigarette in wave 1 and wave 3 with the p value < 0.001 in Thailand and Malaysia.

Awaisu et al. [26] compared non-smokers and smokers in perceiving pictorial warnings to alter smoking cessation behaviours, and the result found significantly different (p value < 0.001). Additionally, when comparing abstract and real pictures in influencing the intention to quit smoking, Wu, et al. [15] found a significant difference between those types (p value = 0.025). Moreover, the authors found that there was a significant difference between a picture with less graphic and that with more graphic (p value = 0.001). Similarly, Elton-Marshall, et al. [18] found that there was a difference after the changes of health warnings on cigarette packs (p value < 0.001) in China compared to that in Malaysia. The perceived effectiveness of pictorial health warnings measured by the studies can be seen in Table 5.

Discussion

In this study, we explored original research findings on perceptions of the effectiveness of pictorial health warnings on cigarette packs in Asian countries with varying methods, study populations and components measured. Using a literature review, we analyse three main variables: people’s reactions to pictorial health warnings, perceived effectiveness of pictorial health warnings in deterring smoking initiation, and perceived effectiveness of pictorial health warnings in stimulating smoking cessation. This study is useful to evaluate the implementation of pictorial health warnings on cigarette packs in Asia.

This study found that there are limited adequate studies evaluating the effectiveness of Pictorial health warnings in Asian countries that were published online, meaning that there might be more studies on Pictorial health warnings that have not been published yet or were published in other languages besides English and Indonesian. However, the existing articles in this study could describe effectiveness of pictorial health warnings in Asian countries. Our finding is consistent with a report by The Union [27] revealing that Asian countries have made significant progress in implementing and strengthening pictorial health warnings. In line with that, our reviewed studies showed that several countries including China, Jordan, and Turkey proposed new pictorial warnings indicating those countries were strengthening pictorial health warnings on cigarette packs by updating the pictures. Furthermore, Thailand, which implemented pictorial warning labels on 50% of front and back of cigarette packs in 2005, increased the size of the warning up to 85% covered on both sides. It shows that some Asian countries exerted to implement a more effective pictorial health warning to overcome the impacts of smoking behaviour [27].

Another report revealed that almost all countries in southeast Asia have carried out an efficacy testing of their pictorial health warnings [28]. Similarly, our findings also showed that several studies had been conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of pictorial health warnings on smoking intention and smoking behaviour as well as people’s reactions to them. Our study found that new or larger pictorial warnings could increase the salience, cause more fear, and gain more information and knowledge about the health risk of smoking behaviour. Those effects were not only occurred among smokers but also non-smokers. A study in the United States showed that the graphic warning increased perceived harms [29]. A previous study also suggested that the characteristics of a warning might influence the extent to which the warning will be noticed and recalled, which later generate reactions [30]. A regular introduction of a new message or warning was known to be able to maintain or even increase warning salience [31]. New design labels with efficacy and threat messages can play a role in efficacy beliefs by affecting held beliefs salient, especially among low SES populations [32].

Furthermore, a study on individual-level psychological outcomes as a result of exposure to pictorial health warnings showed that the warnings might change the smoking-related intentions and behaviours [33]. Previous studies also revealed that graphic warning labels are obviously more effective than text-only labels in promoting changes in attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, intentions to quit as well as quit attempts [11, 34,35,36]. It is in line with our finding which shows that pictorial health warnings in Asian countries generated different effects on smoking behaviour when compared to text-only warnings. However, there are limited studies on the association between the increase in warning size and quit rate in Asia. As a result, the real efficacy, besides the perceived efficacy, of pictorial health warnings in Asia cannot be actually measured.

Conclusion

Asian countries have significantly made prominent progress in implementing and strengthening Pictorial health warnings. The reviewed studies show the measurements of the perceived effectiveness of pictorial health warnings had been conducted in several countries. When comparing pictorial warnings and text-only warnings, all studies suggested that pictorial warnings are more effective in changing knowledge, attitude, salient, smoking intention, and quit intention. Moreover, the reviewed studies also revealed that larger and new pictorial warnings are required to be introduced regularly to maintain behaviour salience. However, the relationship between pictorial health warnings and quit rate needs to be measured in future studies, as well as the effective period to change or refresh pictorial health warnings.

Abbreviations

- FCTC:

-

Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

- PHWs:

-

Pictorial Health Warnings

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- SES:

-

Socio-economic Status

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Mackay J, Ritthiphakdee B, Reddy KS. Tobacco control in Asia. Lancet. 2013;381(9877):1581.

World Health Organization. Conference of the parties to the WHO framework convention on tobacco control: decisions. Geneva: WHO; 2011.

Aditama TY, Pradono J, Rahman K, Warren CW, Jones NR, Asma S, et al. linking global youth tobacco survey (GYTS) data to the WHO framework convention on tobacco control: the case for Indonesia. Prev Med. 2008;47(Supplement 1):S11–S4.

Fathelrahman AI, Omar M, Awang R, Cummings KM, Borland R, Bin Mohd Samin AS. Impact of the new Malaysian cigarette pack warnings on smokers’ awareness of health risks and interest in quitting smoking. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7(11):4089–99.

Balhara YP, Gupta R. Revised size of pictorial warning on cigarette packages-a step in right direction. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(11):1401–2.

Scollo MM, Winstanley MH. Tobacco in Australia: facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2008.

Peebles K, Hall MG, Pepper JK, Byron MJ, Noar SM, Brewer NT. Adolescents’ responses to pictorial warnings on their Parents’ cigarette packs. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(6):635–41.

Pepper JK, Cameron LD, Reiter PL, McRee A-L, Brewer NT. Non-smoking male Adolescents’ reactions to cigarette warnings. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e65533.

Cameron LD, Williams B. Which images and features in graphic cigarette warnings predict their perceived effectiveness? Findings from an online survey of residents in the UK. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49(5):639–49.

Li HCW, Chan SS, Lam TH. Smoking among Hong Kong Chinese women: behavior, attitudes and experience. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):183.

Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review. Tob Control. 2011;20(5):327.

Strahan EJ, White K, Fong GT, Fabrigar LR, Zanna MP, Cameron R. Enhancing the effectiveness of tobacco package warning labels: a social psychological perspective. Tob Control. 2002;11(3):183–90. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.11.3.183.

Yong H-H, Fong GT, Driezen P, Borland R, Quah ACK, Sirirassamee B, et al. Adult smokers’ reactions to pictorial health warning labels on cigarette packs in Thailand and moderating effects of type of cigarette smoked: findings from the international tobacco control Southeast Asia survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(8):1339–47.

Swartz MK. The PRISMA statement: a guideline for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Pediatr Health Care. 2011;25(1):1–2.

Wu D, Yang T, Cottrell RR, Zhou H, Yang XY, Zhang Y. The effects of tobacco-related health-warning images on intention to quit smoking among urban Chinese smokers. Health Educ J. 2014;74(3):287–98.

Zaidi SM, Bikak AL, Shaheryar A, Imam SH, Khan JA. Perceptions of anti-smoking messages amongst high school students in Pakistan. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:117.

Sychareun V, Hansana V, Phengsavanh A, Chaleunvong K, Tomson T. Perceptions and acceptability of pictorial health warning labels vs text only--a cross-sectional study in Lao PDR. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1094.

Elton-Marshall T, Xu SS, Meng G, Quah AC, Sansone GC, Feng G, et al. The lower effectiveness of text-only health warnings in China compared to pictorial health warnings in Malaysia. Tob Control. 2015;24(Suppl 4):iv6–13.

Mutti S, Reid JL, Gupta PC, Pednekar MS, Dhumal G, Nargis N, et al. Perceived effectiveness of text and pictorial health warnings for smokeless tobacco packages in Navi Mumbai, India, and Dhaka, Bangladesh: findings from an experimental study. Tob Control. 2016;25(4):437.

Awaisu A, Hagi A, Ashour MA, Kheir N. Pictorial health warnings on cigarette packages in Qatar: preimplementation awareness and perceptions of ever-smokers versus never-smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(10):1765–72.

Dien A, Rita D, Amry I, Ferdinand S, James FT, David H, et al. Effectiveness of pictorial health warning labels for Indonesia’s cigarette packages. Depok: Center for Health Research Universitas Indonesia; 2015.

Fong GT, Hammond D, Jiang Y, Li Q, Quah AC, Driezen P, et al. Perceptions of tobacco health warnings in China compared with picture and text-only health warnings from other countries: an experimental study. Tob Control. 2010;19(Suppl 2):i69–77.

Hawari FI, Bader RK, Beano HM, Obeidat NA, Ayub HS, Habashneh MA, et al. Perceptions of young Jordanian adults to proposed anti-tobacco pictorial warning labels. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:414.

Behera BK, Tyagi A, Rani B, Chawla S, Kumar BJ, Sahoo MC. How effective pictorial warnings on tobacco product are? A cross sectional study from North India. Indian J Health Wellbeing. 2013;4(5):1108–11.

Tugrul TO. The impacts of fear and disgust on the perceived effectiveness of smoking warning labels. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2013;27(2):NP506–NP12.

Auemaneekul N, Silpasuwan P, Sirichotiratana N, Satitvipawee P, Sompopcharoen M, Viwatwongkasem C, et al. The impact of cigarette plain packaging on health warning salience and perceptions: implications for public health policy. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015;27(8):848–59.

The Union. The Union Asia Pacific Region in 2016: Increase in Graphic Health Warnings on Tobacco Packs 2016.

Omar M, Damayanti R, Vanphanom M. Regional efficacy testing graphic health warnings in Asean countries of Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, And Vietnam. 2008.

Popova L, Ling PM. Nonsmokers’ responses to new warning labels on smokeless tobacco and electronic cigarettes: an experimental study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):997.

Noar SM, Hall MG, Francis DB, Ribisl KM, Pepper JK, Brewer NT. Pictorial cigarette pack warnings: a meta-analysis of experimental studies. Tob Control. 2016;25(3):341.

Hoek J, Gendall P, Louviere J. Rationalisation as delusion: pictorial health warnings and tobacco industry arguments. J Consum Mark. 2011;28(7):476–83.

Mead EL, Cohen JE, Kennedy CE, Gallo J, Latkin CA. The influence of graphic warning labels on efficacy beliefs and risk perceptions: a qualitative study with low-income, urban smokers. Tob Induc Dis. 2016;14:25.

Thrasher JF, Abad-Vivero EN, Huang L, O'Connor RJ, Hammond D, Bansal-Travers M, et al. Interpersonal communication about pictorial health warnings on cigarette packages: policy-related influences and relationships with smoking cessation attempts. Soc Sci Med. 2016;164:141–9.

Miller CL, Hill DJ, Quester PG, Hiller JE. Impact on the Australian Quitline ofnew graphic cigarette pack warnings including the Quitline number. Tob Control. 2009;18(3):235–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2008.028290.

Bansal-Travers M, Hammond D, Smith P, Cummings KM. The impact of cigarette pack design, descriptors, and warning labels on risk perception inthe U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(6):674–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.01.021.

Miller CL, Quester PG, Hill DJ, Hiller JE. Smokers’ recall of Australian graphic cigarette packet warnings & awareness of associated health effects, 2005–2008. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:238. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-238.

Acknowledgements

All authors express their sincere gratitude to reviewers and the co-editors of The BMC Public Health Journal for the constructive advice.

Funding

This study is supported by Universitas Indonesia through the International Indexed Publication grant program.

Availability of data and materials

All data analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SPR contributed to the main idea/topic and to the systematic search of research articles. SPR was responsible most in the development of the study report and manuscript. DS supervised the whole process of this study and contributed mostly to the selection of research articles and determination of study method. All authors gave contributions to the interpretation and analysis of the findings as well as the development of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ratih, S.P., Susanna, D. Perceived effectiveness of pictorial health warnings on changes in smoking behaviour in Asia: a literature review. BMC Public Health 18, 1165 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6072-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6072-7