Abstract

Background

WHO developed a global strategy to eliminate hepatitis B by 2030 and set target to treat 80% of people with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection eligible for antiviral treatment. As a first step to achieve this goal, it is essential to conduct a situation analysis that is fundamental to designing national hepatitis plans. We therefore estimated the prevalence of chronic HBV infection, and described the existing infrastructure for HBV diagnosis in Madagascar.

Methods

We conducted a stratified multi-stage serosurvey of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in adults aged ≥18 years using 28 sentinel surveillance sites located throughout the country. We obtained the list of facilities performing HBV testing from the Ministry of Health, and contacted the person responsible at each facility.

Results

A total of 1778 adults were recruited from the 28 study areas. The overall weighted seroprevalence of HBsAg was 6.9% (95% CI: 5.6–8.6). Populations with a low socio-economic status and those living in rural areas had a significantly higher seroprevalence of HBsAg. The ratio of facilities equipped to perform HBsAg tests per 100,000 inhabitants was 1.02 in the capital city of Antananarivo and 0.21 outside the capital. There were no facilities with the capacity to perform HBV DNA testing or transient elastography to measure liver fibrosis. There are only five hepatologists in Madagascar.

Conclusion

Madagascar has a high-intermediate level of endemicity for HBV infection with a severely limited capacity for its diagnosis and treatment. Higher HBsAg prevalence in rural or underprivileged populations underlines the importance of a public health approach to decentralize the management of chronic HBV carriers in Madagascar by using simple and low-cost diagnostic tools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a DNA virus belonging to the Hepadnaviridae family. It is estimated that at least two billion people have been infected with HBV, and 240 million individuals suffer from chronic HBV infections [1]. Chronic HBV infection is a major risk factor for liver disease, including liver cancer [2], one of the most frequent malignancies in Africa [3]. Hepatitis B has been largely ignored as an important global health priority until recently [4], despite the heavy disease burden. In 2015, the United Nations adopted the resolution in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, in which viral hepatitis became one of the targeted infectious diseases within the United Nations’ development goals. Subsequently, the World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a strategy to eliminate HBV as a public health threat by 2030, aiming to reduce the incidence of new chronic infections by 90% and HBV-related mortality by 65%. Increasing the coverage of HBV testing and antiviral treatment became one of the important targets [4], and the feasibility of a community-based HBV screening and linkage to care with antiviral therapy in resource-limited settings was recently demonstrated by the PROLIFICA project in West Africa [5].

Madagascar is a large island located in the Indian Ocean close to the southeast of the African continent, with 23.5 million inhabitants. Although the hepatitis B vaccine was integrated into the national immunization program in 2002, vaccination is only provided as part of the pentavalent vaccine given after the age of 6 weeks, without scheduling a dose at birth. Moreover, the coverage of three doses of hepatitis B vaccine in infants was estimated at 69% in 2015, which is inadequate [6]. There is no national hepatitis plan or program to screen, diagnose, or treat chronic HBV carriers. A recent systematic review of the global seroprevalence of HBsAg using data from seven previous serosurveys reported a pooled estimate of 4.6% (95% CI: 4.4–4.8%) in Madagascar [1]. However, these surveys were limited because they only sampled participants from one or two locations in the country [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

As a first step to achieve the WHO’s global elimination strategy, it is essential to better estimate HBV prevalence in the population before designing national strategies. We therefore conducted a country-wide serosurvey to estimate the seroprevalence of HBsAg in adults in Madagascar and to identify factors associated with it. We also described the current infrastructure for HBV testing and treatment in the country.

Methods

Study population

We conducted a stratified multi-stage sample serosurvey between November 2011 and May 2013. We used sentinel surveillance sites for febrile illness as a primary sampling unit to obtain representative samples of the general population in Madagascar, because these are evenly scattered throughout the country [15]. We excluded three of 31 health centres that participate in this surveillance system (Maroantsetra, Sainte Marie, and Maintirano) because access to these sites required air travel. The remaining 28 sites were used to select study villages (Fig. 1). We stratified the coverage area of each of the 28 health centres into ‘central’ and ‘peripheral’ depending on the distance from the health centre. Then, by using a random number generator (Excel, Microsoft) we randomly selected one village from a central area and another from a peripheral area. Overall, we assessed 28 central villages and 28 peripheral villages. We randomly selected households in each village, and the team of fieldworkers visited these selected households until they could recruit at least 31 adults aged ≥18 years.

Following written informed consent, we administered a standardised epidemiological questionnaire and obtained a venous blood sample from study participants. Collected serum samples were transported to the Virology Unit of the Pasteur Institute of Madagascar, and stored at −80 °C.

Serological assay

We detected HBsAg using an in-house ELISA that was validated at our Virology unit. The in-house assay had good diagnostic accuracy for the detection of HBsAg (sensitivity, 95.6% (95% CI, [78.05, 100]; specificity, 100% (95% CI, [80.36, 100], using a commercial chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (Architect®, Abbott, USA) as a reference. Briefly, for the in-house capture-ELISA, a goat polyclonal anti-HBs antibody (Reference ABIN731303, Germany) was first used. After binding of the sera, a second goat polyclonal (biotin) antibody (Reference ABIN731305, Germany) was used. At the end of the reaction, Streptavidin-HRP conjugate (Reference RPN 1231 - AEC Amersham) was added before the revelation step using ABTS® (Sigma-Aldrich).

Sample size calculation

Assuming that the expected seroprevalence of HBsAg is 10% and the desired width of the 95% confidence interval is ±2% with a design effect of 2.0 [16], the minimum sample size required was 1729. We recruited at least 31 adults per village since there were 56 villages studied.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA IC. 11.0 (Stata Corporation, USA). The seroprevalence of HBsAg was estimated by dividing the number of HBsAg-positive people by the number of survey participants. The estimates were weighted for sampling probability and adjusted for stratification by central or peripheral area and clustering in the survey design, using the “svy” command in STATA. Similarly, a weighted logistic regression, that accounted for stratification and clustering by village, was used to identify factors associated with HBsAg seropositivity. The factors of interest included basic demographic variables (age and sex) and potential barriers to linkage from HBsAg screening to care (education levels, socio-economic status (SES), and area of residency) [17,18,19]. After univariable analysis, the associations between these covariates and HBsAg seropositivity were adjusted for age and sex in multivariable logistic regression models.

We used principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) to define the SES of each individual. We included the following variables known to represent the SES in the PCA: type of wall, floor, and roof material; type of energy for light and cooking; sanitation facility; and main assets [20,21,22]. Hierarchical cluster analysis was performed using raw individual weights obtained from preliminary PCA using Ward method. Consolidation was performed using k-means methods. We classified the villages into three groups: urban, semi-urban, and rural (Fig. 1). The urban area was defined to be within an administrative centre of a district and located on the main road that connects the main Provinces to the capital Antananarivo. The semi-urban area is also within an administrative centre of a district, but not on the main national road. We categorised a village as rural when none of the above criteria were met. There is at least one regional hospital in the urban areas, whereas there is at least one district hospital in the semi-urban areas. There are no hospitals in the rural areas; only a primary health care centre.

Infrastructure for HBV testing/treatment in Madagascar

We determined the number of laboratories or health facilities that routinely carry out each of the following tests essential for HBV screening and clinical staging: HBsAg serology, determination of alanine (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels, detection or quantification of HBV DNA, transient elastography (Fibroscan®), and liver biopsy. We also determined the number of hepatologists and pharmacies that routinely dispense antiviral drugs (lamivudine or tenofovir). In April 2016, we first requested the Ministry of Health to generate a list of facilities including information on each of these items. Subsequently we verified the list by contacting a person responsible at each facility using a standardised questionnaire. We also gathered data on the cost of each service. We presented the ratio of the number of facilities with the capacity to test individuals for chronic HBV infection per 100,000 inhabitants, a method proposed by the WHO [23].

Results

Seroprevalence of HBsAg

A total of 1778 participants were recruited from the 28 study areas. Approximately half (50.6%) were men. The mean age was 37.7 years (SD ± 14.4) and ranged from 18 to 99 years. The overall weighted seroprevalence of HBsAg was 6.9%, 95% CI [5.6–8.6] (141/1778). The prevalence varied markedly between villages, ranging from 0.0% to 26.7%.

Factors associated with HBsAg seropositivity

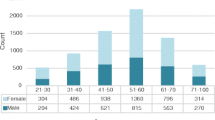

Table 1 presents the factors associated with HBsAg seropositivity. There was no clear association between either age group or sex and the seroprevalence of HBsAg. The seroprevalence of HBsAg in women of childbearing age (18–45 years old) was 6.2%, 95% CI [3.4–8.9] (46/630) (Fig. 2).

Variable characterizing low socio economical level were mainly wooden combustion use, roof made in plants, light of the petroleum lamp, dirt floor in the bedroom and not equipped with toilet (v-test were respectively 31.0, 30.5, 26.05, 24.02 and 22.16); variables characterizing intermediated socio-economical level were wood charcoal combustion, sheet roof, electricity light, TV and cement floor (v-test = 26.2, 25.9, 23.5, 22.9 and 22.0, respectively); variables characterizing the highest socio-economical level were computer owning, flash toilet owning, internet access, car and refrigerator owning (v-test were respectively 31.9, 26.5, 26.0, 22.4 and, 21.8). Repartition of characteristic variables in each SES level were described in Additional file 1: Table S1. Of the three potential barriers to linkage to care, low SES and living in a rural area were significantly associated with HBsAg seropositivity after adjusting for age and sex. The middle and high SES groups had a seroprevelance of HBsAg that was 0.70 [0.42–1.17] and 0.39 [0.14–1.11] times, respectively, that of the low category SES group (adjusted p for Wald test for trend = 0.03). Using the participants living in urban areas as the reference, the odds ratios were 1.23 [0.71–2.11] for semi-urban and 1.69 [1.09–2.60] for rural areas (adjusted p for Wald test for trend = 0.04).

Infrastructure for HBV testing/treatment

Table 2 summarises the current infrastructure for HBV screening, clinical staging, and treatment in Madagascar. There were 77 laboratories routinely equipped to perform HBsAg serology and liver enzyme tests (AST and ALT). Although many have the capacity to perform ELISA tests, only three laboratories in the capital routinely performed ELISA assays for HBsAg detection, whereas the rest used immunochromatographic point-of-care assays. These 77 facilities cover only 31 of the 114 administrative districts. Thirty-six (46.8%) of the laboratories are located in the capital, resulting in a ratio of 1.03 facilities per 100,000 inhabitants in the capital region and 0.21 per 100,000 inhabitants outside. Furthermore, many of these laboratories are not fully functional throughout the year because of limited resources, frequent reagent shortages, and laboratory equipment failure.

There are only five hepatologists in the country (0.08 and 0.01 per 100,000 inhabitants in Antananarivo and outside of the capital region, respectively). Three are in the capital: two at the largest public medical centre and one at a peripheral public hospital. Two others are in two hospitals outside the capital region in Fianarantsoa and in Mahajanga. None of the hepatologists routinely perform liver biopsies, and only a few surgeons occasionally perform the procedure. There is no Fibroscan® device and none of laboratories performs PCR assays for HBV DNA. When HBV DNA measurement is requested, sera are shipped to a commercial laboratory in France from the Pasteur Institute of Madagascar. Lamivudine is available in only one pharmacy in the capital, and no pharmacy dispenses tenofovir, even though the national authority has approved it.

Discussion

We conducted a stratified multi-stage sample serosurvey to estimate the seroprevalence of HBsAg in Madagascar. We found that: (i) Madagascar has a high-intermediate level of endemicity of HBV infection, according to the WHO classification [1], with a weighted prevalence of 6.9%; and (ii) people with a low SES and those living in rural areas are more likely to be HBsAg seropositive. We also revealed a severely limited capacity for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic HBV in Madagascar.

This is the first study that attempted to estimate the seroprevalence of HBsAg in Madagascar using a representative sample of the country. The prevalence was weighted to reflect the probability of being included in the survey [16]. There have been 12 serosurveys for HBsAg in Madagascar to date (Table 3). However, these only focused on high-risk groups or a few communities within the country. By pooling data from these studies, a country-specific prevalence was recently estimated by Schweitzer et al. (4.6%, 95% CI [4.4–4.8]), which was much lower than our estimate (6.9%, 95% CI [5.6–8.6]). Their pooled estimate was low because of a large influence from one large study of blood donors in the capital, Antananarivo, (n = 47,597) which reported a prevalence of 3.8% [13]. The prevalence in the capital is lower than in other regions [5], and the risk of HBV infection in blood donors is likely to differ from that of the general population, possibly leading to an erroneous estimate.

To reduce HBV-related mortality in Madagascar, hepatitis B vaccination alone is insufficient because 6.9% of adults who established chronic infection before the introduction of hepatitis B vaccines will continue to carry elevated risk of dying from HBV-related liver diseases. Alternatively, population-wide screening and treatment of HBV may reduce these deaths, as suggested by a recent modelling study [24]. We assessed factors associated with HBsAg seropositivity to identify sub-groups of the population with an increased risk of chronic HBV infection. Such information may help in the planning of a future “HBV screen and treat” program in Madagascar. We found that the prevalence did not vary significantly according to age or sex. However, we identified that people with a low SES and those living in rural communities have high HBV prevalence (9.4% and 9.8%, respectively). This is problematic as both low SES and rural residence are known barriers to access to healthcare in sub-Saharan Africa [18, 19]. The WHO recommends a public health approach to scaling up HBV testing and treatment, by ensuring the “widest possible access to high-quality services at the population level” [25]. Our results support the importance of this approach, and suggest that special care must be taken to not overlook underprivileged people or those in rural areas, not only to be equitable, but also because of the higher HBV prevalence in these populations.

Although the current infrastructure for “HBV screen and treat” in Madagascar is very limited, we still believe that screening, clinical staging, and treatment of people with chronic HBV infection will become feasible through the use of alternative diagnostic tools, as recommended in the WHO treatment guidelines [25]. First, HBsAg detection by ELISA is only performed in three laboratories in the capital and none in other regions. However, immunochromatographic point-of-care tests are available in many laboratories in the capital region and to a lesser extent in rural areas at an affordable price (2–5 USD/test). The high diagnostic accuracy of HBsAg point-of-care tests has been confirmed under field conditions in sub-Saharan Africa [26]. Second, although there is no Fibroscan® and liver biopsy is rarely performed in Madagascar, many laboratories still have the capacity to test AST and ALT. The WHO recommends the use of simple non-invasive markers for fibrosis staging such as APRI or Fib-4, and these only require basic laboratory markers including transaminase (AST, ALT) and platelet count. Third, the lack of capacity to evaluate HBV DNA levels seems to be a problem as its measurement is essential to define treatment eligibility according to European or American guidelines [27, 28]. However, the recent WHO guidelines acknowledged the lack of access to HBV DNA testing in low- and middle-income countries, and defined separate treatment criteria for places where HBV DNA testing is not available. These alternative criteria do not depend on HBV viral load; they only require ALT levels and an APRI score [25]. Although tenofovir is currently unavailable in Madagascar, the cost of antivirals does not need to be an obstacle as its generic version (50–350 USD/year) can be used. The most serious obstacle may be the lack of a sufficient healthcare workforce; there are only 0.02 hepatologists/100,000 inhabitants. Task shifting of HBV clinical management from hepatologists to mid-level health workers (e.g., registered nurses) needs to be carefully considered.

Our study has limitations. First, although we attempted to provide an estimate that represents the entire country, we excluded three of 31 sentinel sites because of difficulties of access. However, the effect should be minimal as the number of inhabitants covered by these sites is relatively small. Second, we only studied people aged 18 years or above, and did not assess the prevalence in children. This was the requirement from the funder of this study and sampling of children was therefore, not authorized by the local IRB. It is to be noted that we are currently conducting a study focusing on prevention of HBV in children called NéoVac (Neonatal Vaccination against Hepatitis B in Africa), which attempts to understand potential barriers to implement timely birth dose vaccination in Madagascar, Senegal and Burkina Faso. Third, we did not provide care for those who were identified to be positive for HBsAg during the serosurvey. When the study was planned in 2011, this was not required by the national ethics committee.

Conclusion

The WHO has set a target to treat 80% of eligible people with chronic HBV infection to eliminate hepatitis B as a public health threat by 2030; globally, only 8% of this population was estimated to be under treatment in 2015 [29]. It is crucial to adopt a public health approach that ensures the widest possible access to HBV screening and care at the population level to achieve this goal in resource-limited countries [4]. Our study demonstrated a higher seroprevalence of HBsAg in rural areas where the access to HBV testing is limited, and in people with a low SES who may be unable to pay for HBV testing and treatment. This clearly requires the need to decentralize the management of chronic HBV carriers in Madagascar by using simple and low-cost diagnostic tools. A similar exercise deserves to be carried out in other low- and middle-income countries as this may help in designing an evidence-based national hepatitis plan.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

Alanine transferase

- AST:

-

Aspartate transferase

- CDC:

-

Center for disease control

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DNA:

-

Desoxyribonucleic acid

- ELISA:

-

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- HBsAg:

-

Hepatitis B surface antigen

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B Virus

- HCA:

-

hierarchical cluster analysis

- IC:

-

immunochromatography

- PCA:

-

principal component analysis

- PHA:

-

Passive hemmaglutination

- PROLIFICA:

-

Prevention of liver fibrosis and cancer in Africa

- SES:

-

socio-economic status

- WHO:

-

World health organization

- ZORA:

-

Zoonoses, rodent and arboviruses

References

Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, Krause G, Ott JJ. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(10003):1546–55.

Shimakawa Y, Lemoine M, Njai HF, Bottomley C, Ndow G, Goldin RD, Jatta A, Jeng-Barry A, Wegmuller R, Moore SE, et al. Natural history of chronic HBV infection in West Africa: a longitudinal population-based study from the Gambia. Gut. 2016;65(12):2007–2016.

Jemal A, Bray F, Forman D, O'Brien M, Ferlay J, Center M, Parkin DM. Cancer burden in Africa and opportunities for prevention. Cancer. 2012;118(18):4372–84.

WHO: Draft global health sector strategies. Viral hepatitis, 2016–2021. 2015.

Lemoine M, Shimakawa Y, Njie R, Taal M, Ndow G, Chemin I, Ghosh S, Njai HF, Jeng A, Sow A, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of a screen-and-treat programme for hepatitis B virus infection in the Gambia: the prevention of liver fibrosis and cancer in Africa (PROLIFICA) study. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(8):e559–67.

WHO. WHO-UNICEF estimates of HepB3 coverage. 2017.

Boisier P, Rabarijaona L, Piollet M, Roux JF, Zeller HG. Hepatitis B virus infection in general population in Madagascar: evidence for different epidemiological patterns in urban and in rural areas. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;117(1):133–7.

Dupinay T, Restorp K, Leutscher P, Rousset D, Chemin I, Migliani R, Magnius L, Norder H. High prevalence of hepatitis B virus genotype E in northern Madagascar indicates a west-African lineage. J Med Virol. 2010;82(9):1515–26.

Migliani R, Rakoto Andrianarivelo M, Rousset D, Rabarijaona L, Randrianarisoa P, Roux JF. Seroprevalence of viral hepatitis B in the city of Mahajanga, Madagascar in 1999. Med Trop (Mars). 2000;60(2):146–50.

Morvan JM, Boisier P, Andrianimanana D, Razainirina J, Rakoto-Andrianarivelo M, Roux JF. Serological markers for hepatitis a, B and C in Madagascar. First investigation in a rural area. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1994;87(3):138–42.

Oddou A. L'antigène Australia chez les donneurs de sang de l'hôpital Girard et Robic à Tananarive. Arch Inst Pasteur Madagascar. 1972;41:109–11.

Randriamahazo TR, Raherinaivo AA, Rakotoarivelo ZH, Contamin B, Rakoto Alson OA, Andrianapanalinarivo HR, Rasamindrakotroka A. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus serologic markers in pregnant patients in Antananarivo, Madagascar. Med Mal Infect. 2015;45(1–2):17–20.

Randriamanantany AZ, Hendrison RD, Elie RF, Tantely RM, Ramamonjisoa A, Barnia RF, Paquerette HS, Raft HF, Aimee RA, Andry R. The seroprevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen among first time blood donors in Antananarivo (Madagascar) from 2003 to 2009. Blood Transfus. 2011;9(4):475–7.

Ravaoarinoro M, Ratsirahonana S, Raelison M, Phillipon G, Coulanges P. Testing for Australia antigen in Madagascans of the Antananarivo region. Arch Inst Pasteur Madagascar. 1985;52(1):157–63.

Randrianasolo L, Raoelina Y, Ratsitorahina M, Ravolomanana L, Andriamandimby S, Heraud JM, Rakotomanana F, Ramanjato R, Randrianarivo-Solofoniaina AE, Richard V. Sentinel surveillance system for early outbreak detection in Madagascar. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:31.

WHO: Documenting the Impact of Hepatitis B Immunization: best practices for conducting a serosurvey. In; 2011.

Govindasamy D, Ford N, Kranzer K. Risk factors, barriers and facilitators for linkage to antiretroviral therapy care: a systematic review. AIDS. 2012;26(16):2059–67.

Lankowski AJ, Siedner MJ, Bangsberg DR, Tsai AC. Impact of geographic and transportation-related barriers on HIV outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(7):1199–223.

Mugglin C, Estill J, Wandeler G, Bender N, Egger M, Gsponer T, Keiser O, Ie DEASA. Loss to programme between HIV diagnosis and initiation of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Tropical Med Int Health. 2012;17(12):1509–20.

Barros AJ, Victora CG. A nationwide wealth score based on the 2000 Brazilian demographic census. Rev Saude Publica. 2005;39(4):523–9.

Ferguson B, Tandon E, Gakidou E, Murray CJL. Estimating permanent Income using Indicator variables. Geneva: World health organization; 2003.

Vyas S, Kumaranayake L. Constructing socio-economic status indices: how to use principal components analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21(6):459–68.

WHO: Monitoring and evaluation for viral hepatitis B and C: recommended indicators and framework. 2016.

Nayagam S, Thursz M, Sicuri E, Conteh L, Wiktor S, Low-Beer D, Hallett TB. Requirements for global elimination of hepatitis B: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(12):1399–408.

WHO. Guidelines for the prevention, care and treatment of persons with chronic hepatitis B infection. In.; 2015.

Njai HF, Shimakawa Y, Sanneh B, Ferguson L, Ndow G, Mendy M, Sow A, Lo G, Toure-Kane C, Tanaka J, et al. Validation of rapid point-of-care (POC) tests for detection of hepatitis B surface antigen in field and laboratory settings in the Gambia, western Africa. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(4):1156–63.

European Association For The Study Of The L. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57(1):167–85.

Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Murad MH, American Association for the Study of Liver D. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63(1):261–83.

WHO: Global Hepatitis Report, 2017. 2017.

Capdevielle P, Valmary J, Coignard A, Pecarrere J, Boudon A, Delprat J, Guintran JL, Laroche R. Distribution of HBs antigen in Tananarive (author's transl). Med Trop (Mars). 1979;39(6):685–7.

Mathiot C, Coulanges P, Rakotondraibe J, Pique G. Research on anti-LAV antibodies and HBs antigens in certain population groups in Madagascar. Arch Inst Pasteur Madagascar. 1987;53(1):129–31.

Genin C, Mouden JC, Coulanges P, Randriambololona R, Cassel-Beraud AM, Michel P, Croquet O. Evaluation of the prevalence of 3 markers (HIV antibodies, anti-treponema antibodies, HBs antigen) of sexually transmitted diseases in so-called "at risk" subjects in Madagascar. Arch Inst Pasteur Madagascar. 1988;54(1):197–216.

Rasamindrakotroka AJ, Ramiandrisoa A, Rahelimiarana N, Radanielina R, Kirsch T, Rakotomanga S. Donneurs de sang de la région tananarivienne : estimation de la séroprévalence de la syphilis, de l'hépatite B et de l'infection à VIH. Med Mal Infect. 1993;23(1):40–1.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the population of Madagascar who participated in this study. We thank those who facilitated the survey, i.e., the head authorities of Fokontany, local administration authorities and health authorities from the Ministry of Health. We also thank all the staff from the Plague Unit at the Institut Pasteur de Madagascar for data collection and support during field work. We thank Florian Girond for generating the map.

Funding

This study was supported in part by funds raised by the Institut Pasteur de Madagascar. Human field work was funded by the Institut Pasteur of Madagascar (Internal Project through the ZORA (ZOonoses, Rodent, and Arboviruses) project and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Cooperative Agreement #U51/IP000327). The views and conclusions contained in this paper are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either explicit or implicit, of the U. S. Department of Homeland Security.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article as supplementary information files Additional file 2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SFA, JMH, MMO and CR designed the study and participated in the elaboration of the protocol, SFA analysed results and wrote the manuscript; YS participated in statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript; FR participated in designing protocol, editing manuscript and figure; TMA, JPR and SA participated in fields and bench work; JMH and IR corrected manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ministry of Public Health and the National Ethics Committee of Madagascar (authorization N° 066/MSAMP/CE, 26th July 2011; amendment 18th October 2011). Each participant signed an informed consent form before being included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Characteristics of household according to socio-economical level defined by PCA followed by HCA. (DOCX 16 kb)

Additional file 2:

This file includes supplementary data. (CSV 90 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Andriamandimby, S.F., Olive, MM., Shimakawa, Y. et al. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection and infrastructure for its diagnosis in Madagascar: implication for the WHO’s elimination strategy. BMC Public Health 17, 636 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4630-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4630-z