Abstract

Background

Globally, there is a growing concern over pesticides use, which has been linked to self-harm and suicide. However, there is paucity of research on the epidemiology of pesticides poisoning in Nepal. This study is aimed at assessing epidemiological features of pesticides poisoning among hospital-admitted cases in selected hospitals of Chitwan District of Nepal.

Methods

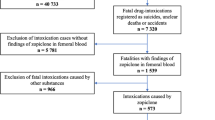

A hospital-based quantitative study was carried out in four major hospitals of Chitwan District. Information on all pesticides poisoning cases between April 1 and December 31, 2015, was recorded by using a Pesticides Exposure Record (PER) form.

Results

A total of 439 acute pesticides poisoning cases from 12 districts including Chitwan and adjoining districts attended the hospitals during the 9-month-long study period. A majority of the poisoned subjects deliberately used pesticides (89.5%) for attempted suicide. The total incidence rate was 62.67/100000 population per year. Higher annual incidence rates were found among young adults (111.66/100000 population), women (77.53/100000 population) and individuals from Dalit ethnic groups (98.22/100000 population). Pesticides responsible for poisoning were mostly insecticides (58.0%) and rodenticides (20.8%). The most used chemicals were organophosphates (37.3%) and pyrethroids (36.7%). Of the total cases, 98.6% were hospitalized, with intensive care required for 41.3%. The case fatality rate among admitted cases was 3.8%.

Conclusions

This study has indicated that young adults, females and socially disadvantaged ethnic groups are at a higher risk of pesticides poisoning. Pesticides are mostly misused intentionally as an easy means for committing suicide. It is recommended that the supply of pesticides be properly regulated to prevent easy accessibility and misuse. A population-based study is warranted to reveal the actual problem of pesticides exposure and intoxication in the community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Despite the associated benefits of pesticides use in increasing agricultural production, there have been growing concerns over the adverse effects of unsafe and inappropriate handling of pesticide to human health [1, 2]. Human exposures to pesticides are a common phenomenon in developing countries like Nepal [3,4,5] because of its easy access and widespread use in agriculture [6, 7]. Studies have shown that pesticides exposure has significant negative impacts on human health, this including acute severe poisoning leading to death and many chronic health issues [8, 9]. Therefore, pesticides poisoning is becoming a major public health problem worldwide [8, 10, 11].

Cases of acute pesticides poisoning — instances of suicide attempt, mass poisoning from contaminated food, chemical accidents in industries, unintended accidents and occupational exposure (agriculture) — are the most serious health hazards associated with pesticides [8, 12]. In 2002, 186,000 suicidal deaths and 4,420,000 Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYS) — also due to suicidal attempts using pesticides — were attributed to pesticides globally [2]. Acute pesticides poisoning is one of the major causes for emergency visits to hospitals in developing countries, including Nepal [13,14,15,16,17,18]. Deliberate self-poisoning using pesticides accounts for major proportions of all suicide cases [8, 11, 15]. Limited information is available on the pesticides poisoning situation in Nepal as it is not included in the national routine Health Management and Information System (HMIS). This study aimed to identify epidemiological characteristics of acute pesticides poisoning in Chitwan District of Nepal.

Located in the south-central part of the country, Chitwan is one among the 75 districts of Nepal. The area is known for its fertile lands, primarily used for agriculture [19]. According to the latest population and housing census, there are two municipalities and 36 Village Development Committees (VDCs) in Chitwan, which is inhabited by 579,984 people (2.2% of Nepal’s population). Chitwan has an urban-rural ratio of 1:2.05 and a male-female ratio of 1:1.08. The upper caste group (41.41%), disadvantaged ethnic groups (34.67%), relatively advantaged ethnic groups (12.02%) and Dalits (lower caste groups) (9.05%) are the major ethnic groups [20]. Agriculture is the primary occupation in the district with 30.79% of the population engaged in agro-business [21]. Chitwan ranks higher (0.551) in Human Development Index compared to other districts of Nepal and has comparatively better health, education and transportation infrastructures [22]. Chitwan and its neighboring districts are famous for commercial vegetable farming where pesticides are used extensively [23].

Methods

We carried out a hospital-based study in four major hospitals of Chitwan. Bharatpur Hospital and Ratnanagar Hospital are public hospitals while Chitwan Medical College Teaching Hospital (CMCTH) and College of Medical Sciences Teaching Hospital (CoMSTH) are medical college hospitals. These hospitals were purposively selected as people from Chitwan and its neighboring districts mostly visit them for all medical emergencies, including poisoning conditions. Three of these hospitals are located in the district headquarter of Chitwan and provide advance life-supporting care for medical emergencies while the fourth one — Ratnanagar Hospital — is located in Ratnanagar Municipality, which is about 12 km east of the district headquarter and provides only basic care for medical emergencies.

All acute pesticides poisoning cases, as classified in accordance to World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition [24] and attending the hospitals between April 1 and December 31,2015, were selected by using a consecutive sampling method. We prospectively collected primary data by interviewing patients or their nearest kin using a modified WHO Pesticides Exposure Record (PER) form. Supplementary information was gathered by reviewing patients’ records.

In each hospital, at least two officer-level medical staffs (doctors or nurses) were designated as enumerators for data collection. The enumerators checked the patient register of the respective emergency departments every day and followed the acute pesticides poisoning cases, if any, for data collection.

Study variables included socio-demographic characteristics of poisoning cases, circumstances of poisoning, characteristics of the pesticides abused, treatment and outcome status. Descriptive analysis using Statistical Package for Social Sciences 22.0 version was used to calculate proportions and central tendencies. The Chi-square test was applied to test statistical significance of categorical variables. We reported the incidence rate of acute pesticides poisoning for Chitwan District.

Results

From Chitwan and eleven neighboring districts, a total of 439 cases attended the hospitals due to acute pesticides poisoning in the 9 months of the study period. All cases agreed to participate in the study (response rate = 100%). Among them 308 (70.16%), 67 (15.26%), 60 (13.67%) and 4 (0.91%) cases had visited Bharatpur Hospital, CMC Teaching Hospital, CoMS Teaching Hospital and Ratnanagar Hospital, respectively. A very similar pattern in proportions (12.1–14.1%) of cases was observed in all months of study periods except during September (8.7%), November (8.7%) and December (6.4%).

Socio-demographic characteristics of acute pesticides poisoning cases

Females constituted double the pesticides poisoning cases than the males (male: female ratio was 1:1.99) (Table 1). The mean age of the patients was 29.9 years (Standard deviation: 14.8; range: 10 months to 80 years). About three-fourth (74.3%) of the total cases were above 19 years of age with the majority being females (49.2% of the total cases). One-fifth of the cases were adolescents aged between 15 and 19 years while 5.7% were children. Two-third of the cases was females and more than two-third (71.3%) was rural residents. Disadvantaged ethnic group (37.8%), followed by upper caste group (35.5%), were found to be the major ethnic groups with higher proportions of pesticides poisoning cases.

In a majority (89.5%) of the cases, deliberate ingestion of pesticides was performed for self harm while the remaining was accidentally poisoned during its handling or during occupational activities concerning the chemicals. Among adolescent cases, 98.9% and 92.6% among adults used pesticide intentionally to commit suicide, while among children 84.0% cases were poisoned accidentally (p < 0.001). Other socio-demographic variables did not vary significantly from intentional and non-intentional poisoning by pesticides (Table 2).

Incidence of acute pesticides poisoning (for cases from Chitwan District only)

Of the total cases during the study period of 9 months, 269 cases were from Chitwan District. The mid-year population of Chitwan District (population at risk) in the year 2015 was estimated to be 629,799 [21]. The incidence rate of acute pesticides poisoning in Chitwan District was 47.0 per 100,000 population during the 9 months of study.This is equivalent to 62.67/100,000 population per year. The annual incidence rate was higher among females (77.53/100,000 population) than among males (46.64/100,000 population). The highest recorded incidence rate was of the age group 15–29 years (111.66/100,000 population per year) followed by the age group of 30–49 years (74.39/100,000 population per year). The annual incidence was higher among urban residents (71.01/100,000 population) than among rural residents (58.59/100,000 population). Among the ethnic groups, it ranged from 50.46/100,000 in non-Dalit, Terai caste groups to 98.22/100000 population among Dalits. The incidence of intentional pesticides poisoning (55.68/100,000 population) was considerably higher than that of non-intentional pesticides poisoning (6.99/100000 population) (Table 3).

Circumstances of pesticides poisoning

The majority (43.7%) of the cases were poisoned during evening hours (18.01 to 24.00 PM) followed by day time (30.4%) and morning hours (24.1%). The median time of poisoning was 17.22 PM while the mode was 22.00 PM at which 8% of the total cases were poisoned from pesticides. Nearly all cases (99.1%) got poisoned in their own homes. Most (98.2%) of the cases got exposed to pesticides through oral route (Table 4).

The pesticides responsible for poisoning were mostly insecticides (59.9%) and rodenticides (20.8%). Herbicides and fungicides comprised only a small proportion of the cases. The common constituent chemicals were: organophosphate compounds (39.6%), pyrethroids (35.1%) and phosphides (21.6%). Carbamates, organochlorides and dinitrophenyl derivatives contained in smaller proportions (Table 4).

Management of acute pesticides poisoning cases and their outcomes

After exposure to pesticides, the poisoned cases arrived at the hospital within an average of 2 h (median time). Time elapsed between exposure and arrival at the hospital ranged from 10 min to 22 h. While 63 (14.4%) of the cases arrived within 1 h, more than half (59.9%) of the patients reached between 1 and 3 h and a fourth of them consulted a doctor after 3 h or more. While most of the cases (97.0%) were hospitalized in the same hospital where they were first taken to, 10 (2.3%) were immediately referred to other hospitals (hospitals other than the ones mentioned in the study) and 3 (0.7%) were discharged after few hours of observation without being admitted. The median hospital stay duration among total hospitalized cases was 4.0 days, (range: 1–24 days).

Among the hospitalized cases, 176 (41.3%) were treated in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU). The median duration of ICU stay was 4.0 days (range: 1–17 days). Among these cases, 4.1% had local effects, 93.4% had shown systemic effects and 1.4% had both local and systemic effects of pesticides poisoning. In terms of severity, 29.6% were in severe condition, while 32.6% had moderate symptoms and 32.8% had minor symptoms.

Among the total hospitalized cases due to pesticides poisoning, 372 (87.3%) cases recovered while 16 (3.8%) died. The outcome status of 38 (8.9%) cases remained unknown because they either could not be tracked after referral or they left against medical advice (LAMA) or absconded from hospitals. The case fatality rate, therefore, is 4.1%, after excluding the cases whose outcome statuses were not known (Table 5).

Discussion

Acute poisoning by using pesticides remains to be a major cause for emergency visits to the hospitals in developing countries [8, 13, 16, 18, 25, 26]. This prospective hospital-based study explored the situation of pesticides poisoning in an agriculture intensive-district of Nepal. The study population was the total number of pesticides poisoning cases who had visited the hospitals during the study period.

This study showed female predominance in acute pesticides poisonings, which was also a result revealed through prior studies conducted in Nepali hospitals [14, 18, 27]. Not just in the case of pesticides poisoning, females have outnumbered males in acute poisonings of other kinds as well, studies have found [28, 29]. Women are more vulnerable to suicide attempts than their male counterparts in developing countries due to factors like domestic violence, abusive spouse, problematic love and marital relationships and unfavorable socio-cultural practices [7, 25, 30]. Moreover, females are more likely to be engaged in impulsive acts of self-harm [7]. In contrast to higher rural suicidal rates found in several Asian countries [8, 31], a lower rate of pesticides poisoning was observed among rural residents in Chitwan. Higher rates of pesticides poisoning might have been observed among urban residents due to classification bias in defining rural and urban settings as the municipalities of Chitwan District also include villages in the process of urbanizing. The rates were higher among socially disadvantaged ethnic groups like the Dalits (lower caste groups). Social disadvantages, economical deprivation and inequalities are positively associated with higher rates of suicide [8, 32, 33]. As in other studies conducted in Nepal, the study also found young adults (15–29 years) to be highly affected by acute pesticides poisonings [14, 17, 18, 25, 27]. This age group of the population has been found to be at a high risk of self-poisoning from pesticides for attempted suicide in previously conducted South-Asia-based studies as well [7, 25]. Moreover, this age group includes adolescents, students and early career beginners who usually face psycho-emotional problems involving failure in academics, unemployment, economic hardship, difficult love affairs, family pressure etc. Such issues give individuals a negative outlook towards life and are positively associated with suicide attempts [25, 26, 30].

Due to lack of defined population at risk, the calculation of incidence rate for acute pesticides poisoning is difficult in hospital-based studies. Almost all cases of medical emergencies including pesticides poisoning from Chitwan District generally attend or are referred from other hospitals to the study hospitals. The calculated incidence rate of acute pesticides poisoning in Chitwan District comprised only of cases who attended the study hospitals. So, this study might have missed cases who did not consult the study hospitals or those who stayed at their homes ignoring minor symptoms of acute pesticides poisoning which is mostly common in occupational pesticides exposure [34, 35] or those who died before reaching the hospitals. So, the actual incidence rate of acute pesticides poisoning in Chitwan District could be higher than that was calculated in this study.

The study revealed that pesticides poisonings were more likely to occur during evening hours. Almost all cases had been exposed to pesticides in their own homes and most of them intentionally self poisoned to attempt suicide. Pesticides are becoming the first choice of method of suicide in many developing countries [11, 18, 27, 29]. The possible explanation of the timing of pesticides consumption could be psychological conditions such as stress and loneliness during evening hours. Easy access to pesticides at home may stimulate suicidal ideation [36,37,38]. Even in agriculture-based developing countries, the proportion of acute pesticides poisoning from occupational exposure is very low when compared to the use of pesticides for intended self harm [14, 39]. In Nepal and other under-developed countries, farmers in rural regions are engaged in subsistence level agriculture. Although there is pesticides act and regulation to regulate and control of pesticides handling and trade in Nepal [21], in practice, there is no restriction on buying pesticides from the market; and people mostly store their own supply of pesticides within the premises of or nearby their homes. Therefore, easy availability and accessibility of pesticides increases intentional use of pesticides for suicide attempts [5, 7, 8, 25, 36]. One study in rural China indicated that the availability of pesticides at home can trigger suicidal attempts among those who really did not want to die [38].

Farmers can have minor acute symptoms due to occupational pesticides exposure as expected symptoms, and hence, they may not generally seek medical consultation [34, 35]. In contrast to this, in case of intentional use of pesticides and accidental exposure, family members seek emergency medical services immediately; even if the swallowed dose of pesticide is not fatal. This could be a reason why the study has shown a very small proportion of occupational pesticides poisoning. The most commonly used pesticides for poisoning were insecticides and rodenticides; common chemical types were organophosphorous, pyrethroids and zinc phosphides. Other studies in Nepal also concluded with similar results [14, 18, 27]. These chemicals are the mostly used pesticides in Nepal. Zinc phosphide, a rodenticide is readily available even in general convenience stores in Nepal.

Chitwan District has easy access to medical care compared to many other parts of Nepal. So, most of the cases visited hospital within a short period of exposure to pesticides and before complications arose. The fatality rate was lower in comparison to the findings from previous studies in Nepal and other Asian countries [12, 14, 15, 18]. Timely consultation with doctors and the availability of appropriate care in hospitals may have contributed to lowering the rate of fatality from pesticides poisoning.

This hospital-based study might have missed out on cases who did not consult the study hospitals. Similarly, data from one complete year could not be included in the report to show seasonal and monthly variations of pesticides poisoning. So, the estimated annual incidence rate could have been different if the actual pattern of cases was different in the remaining 3 months than in the study period. This study was only focused on poisoning due to pesticides. So, the result could not be compared with other kinds of poisoning and with suicidal attempts by other methods. These may be considered as limitations of this study.

Conclusions

Pesticides are intentionally misused as an easy means for committing suicide. The findings indicated that young adults, females and socially disadvantaged ethnic groups like lower caste groups (Dalits) are at a higher risk of pesticide poisoning. Self poisoning by using pesticides usually occurs at home and during evening hours. The commonly available insecticides (organophosphates and pyrethroids) and rodenticides (zinc phosphides) are the common pesticides that cause poisonings. As this study was limited to hospital settings, a population-based study is needed to reveal the actual problem of pesticide exposure and intoxication. Strong regulatory mechanism with effective implementation of existing pesticide regulation is needed for safe handling/storage of pesticides and to limit easy access of pesticides to the general public. As the pesticides are misused for committing suicides, there is a need for preventive and mental health programs for the vulnerable groups.

Abbreviations

- CISU:

-

Civil Society in Development

- CMCTH:

-

Chitwan Medical College Teaching Hospital

- CoMSTH:

-

College of Medical Sciences Teaching Hospital

- DALYS:

-

Disability-Adjusted Life Years

- NHRC:

-

Nepal Health Research Council

- PER:

-

Pesticide Exposure Record

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Scientists

- VDC:

-

Village Development Committee

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WHO, SEARO:

-

World Health Organization, South East Asian Regional Office

References

Ntzani EE, Chondrogiorgi M, Ntritsos G, Evangelou E, Tzoulaki I. Literature review on epidemiological studies linking exposure to pesticides and health effects. EFSA supporting publication. 2013:159pp.

Prüss-Ustün A, Vickers C, Haefliger P, Bertollini R. Knowns and unknowns on burden of disease due to chemicals: a systematic review. Environ Health. 2011;10(1):1.

Monge P, Partanen T, Wesseling C, Bravo V, Ruepert C, Burstyn I. Assessment of pesticide exposure in the agricultural population of Costa Rica. Ann Occup Hyg. 2005;49(5):375–84.

Michaels S, Muniz J, Lasarev M, Ebbert C. Pesticide exposure and self reported home hygiene: practices in agricultural families. Workplace Health Saf. 2003;51(3):113.

Banerjee I, Tripathi S, Roy AS, Sengupta P. Pesticide use pattern among farmers in a rural district of West Bengal, India. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2014;5(2):313.

Mohanraj R, Kumar S, Manikandan S, Kannaiyan V, Vijayakumar L. A public health initiative for reducing access to pesticides as a means to committing suicide: findings from a qualitative study. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2014;26(4):445–52.

Gunnell D, Eddleston M. Suicide by intentional ingestion of pesticides: a continuing tragedy in developing countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32(6):902–9.

Konradsen F. Acute pesticide poisoning–a global public health problem. Dan Med Bull. 2007;54(1):58–9.

Andersen HR, Debes F, Wohlfahrt-Veje C, Murata K, Grandjean P. Occupational pesticide exposure in early pregnancy associated with sex-specific neurobehavioral deficits in the children at school age. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2015;47:1–9.

Eddleston M, Karalliedde L, Buckley N, Fernando R, Hutchinson G, Isbister G, Konradsen F, Murray D, Piola JC, Senanayake N. Pesticide poisoning in the developing world—a minimum pesticides list. Lancet. 2002;360(9340):1163–7.

Gunnell D, Eddleston M, Phillips MR, Konradsen F. The global distribution of fatal pesticide self-poisoning: systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:357.

Ahuja H, Mathai AS, Pannu A, Arora R. Acute poisonings admitted to a tertiary level intensive care unit in northern India: patient profile and outcomes. J Clin Diagn Res: JCDR. 2015;9(10):UC01.

Eddleston M. Patterns and problems of deliberate self-poisoning in the developing world. QJM. 2000;93(11):715–31.

Gupta S K, P JM: Pesticide poisoning cases attending five major hospitals of nepal. J Nepal Med Assoc 2002, 41(October–December):447–456.

Jaiprakash H, Sarala N, Venkatarathnamma P, Kumar T. Analysis of different types of poisoning in a tertiary care hospital in rural South India. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49(1):248–50.

Ko Y, Kim HJ, Cha ES, Kim J, Lee WJ. Emergency department visits due to pesticide poisoning in South Korea, 2006-2009. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2012;50(2):114–9.

Murali R, Bhalla A, Singh D, Singh S. Acute pesticide poisoning: 15 years experience of a large north-west Indian hospital. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2009;47(1):35–8.

Paudyal B. Poisoning: pattern and profile of admitted cases in a hospital in central Nepal. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2005;44(159):92–6.

Piotrowski M, Ghimire D, Rindfuss R. Farming systems and rural out-migration in Nang Rong, Thailand, and Chitwan Valley, Nepal. Rural Sociol. 2013;78(1):75–108.

National Population and Housing Census 2011 ((Village Development Committee/Municipality)- Chitwan. In., vol. 06. Kathmandu: Central Bureau of Statistics; 2014.

The Pesticide Regulation In. Kathmandu: government of Nepal 1994.

Sharma P, Guha-Khasnobis B, Khanal DR. Nepal human Development report 2014. United Nations Development Programme: In Kathmandu; 2014.

Statistical information on Nepalese Agriculture 2012/13. In. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal, Ministry of Agricultural Development, Agribusiness Promotion and Statistics Division, Agri Statistics section; 2013.

Thundiyil JG, Stober J, Besbelli N, Pronczuk J. Acute pesticide poisoning: a proposed classification tool. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(3):205–9.

Van Der Hoek W, Konradsen F. Risk factors for acute pesticide poisoning in Sri Lanka. Tropical Med Int Health. 2005;10(6):589–96.

Phillips MR, Yang G, Zhang Y, Wang L, Ji H, Zhou M. Risk factors for suicide in China: a national case-control psychological autopsy study. Lancet. 2002;360(9347):1728–36.

Singh D, Aacharya R. Pattern of poisoning cases in Bir Hospital. J Institute Med. 2007;28(1):3–6.

Hovda KE, Bjornaas M, Skog K, Opdahl A, Drottning P, Ekeberg O, Jacobsen D. Acute poisonings treated in hospitals in Oslo: a one-year prospective study (I): pattern of poisoning. Clin Toxicol. 2008;46(1):35–41.

Singh B, Unnikrishnan B. A profile of acute poisoning at Mangalore (South India). J Clin Forensic Med. 2006;13(3):112–6.

Konradsen F, van der Hoek W, Peiris P. Reaching for the bottle of pesticide—a cry for help. Self-inflicted poisonings in Sri Lanka. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(7):1710–9.

Chen Y-Y, Wu KC-C, Yousuf S, Yip PS: Suicide in Asia: opportunities and challenges. Epidemiologic reviews 2011:mxr025.

Lorant V, Kunst AE, Huisman M, Costa G, Mackenbach J. Socio-economic inequalities in suicide: a European comparative study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187(1):49–54.

Manuel C, Gunnell DJ, Van Der Hoek W, Dawson A, Wijeratne IK, Konradsen F. Self-poisoning in rural Sri Lanka: small-area variations in incidence. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):1.

Ncube NM, Fogo C, Bessler P, Jolly CM, Jolly PE. Factors associated with self-reported symptoms of acute pesticide poisoning among farmers in northwestern Jamaica. Arch Environ Occupa Health. 2011;66(2):65–74.

Khan M, Damalas CA. Occupational exposure to pesticides and resultant health problems among cotton farmers of Punjab, Pakistan. Int J Environ Health Res. 2015;25(5):508–21.

Zhang J, Stewart R, Phillips M, Shi Q, Prince M. Pesticide exposure and suicidal ideation in rural communities in Zhejiang province, China. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(10):745–53.

Clarke RV, Lester D: Suicide: closing the exits: transaction publishers; 2013.

Sun L, Zhang J. Characteristics of Chinese rural young suicides: who did not have a strong intent to die. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;57:73–8.

Zhang M, Fang X, Zhou L, Su L, Zheng J, Jin M, Zou H, Chen G. Pesticide poisoning in Zhejiang, China: a retrospective analysis of adult cases registration by occupational disease surveillance and reporting systems from 2006 to 2010. BMJ Open. 2013;3(11):e003510.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all the institutions and individuals (listed below in alphabetical order) for their contributions in this study.

Bharatpur Hospital, Chitwan; Chitwan Medical College Teaching Hospital, Chitwan; College of Medical Science Teaching Hospital, Chitwan; Dialogos, a Danish NGO; Dr. Akshya Pradhan, Resident Doctor, College of Medical Science Teaching Hospital; Dr. Badri Raj Pande, Vice President, Nepal Public Health Foundation; Dr. Dhiraj Keshari, Resident Doctor, College of Medical Science Teaching Hospital; Dr. Rajesh Yadav, Deputy Director, College of Medical Science Teaching Hospital; Dr. Alisha Aryal, Medical Officer, Chitwan Medical College Teaching Hospital; Erik Jors, President, Dialogos, Denmark; Mr. Bhoj Raj Khanal, Public Health Inspector, Ratnanagar Hospital, Chitwan; Mr. Yuba Raj Paudel, Monitoring and Evaluation Officer, Nepal Health Sector Support Program, Ministry of Health, Kathmandu; Ms. Gita Khanal, Nursing Officer, Bharatpur, Hospital, Chitwan; Nepal Public Health Foundation, a Nepali NGO; Ratnanagar Hospital, Chitwan and research participants.

Funding

This research was a component of Farming, Health and Environment Nepal-2013/15 project which was funded by Civil Society in Development (CISU), Denmark. This manuscript was written through individual contributions of the authors.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DG, SKG, ST and DRL collaboratively developed the concept and the design of the study. DG, DRL and PK supported in data collection, data quality assurance and data management. DG and AV analyzed the data and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

DG is a public health professional and the Field Coordinator of “Farming, Health and Environment Nepal-2013/15 project” in Nepal Public Health Foundation, Kathmandu, Nepal. He is also the principal investigator for this study. AV is an Associate Professor of Community Medicine in Kathmandu Medical College, Nepal. ST is an Assistant Professor of Entomology in Agriculture and Forestry University, Nepal. PK is a Senior Consultant Physician in Bharatpur Hospital, Chitwan Nepal; DRL is the Director of CMCTH and Head of emergency medicine department. SKG is a Professor in National Academy for Medical Sciences, Bir Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethical Review Board of Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) provided an ethical approval for the research protocol of this study (Reference number: 181/2015). A written informed consent was taken from each participant prior to involving them in the study. In addition, written permission was obtained from each hospital before starting the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gyenwali, D., Vaidya, A., Tiwari, S. et al. Pesticide poisoning in Chitwan, Nepal: a descriptive epidemiological study. BMC Public Health 17, 619 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4542-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4542-y