Abstract

Background

Few studies have evaluated the effect of adherence to a lifestyle intervention on adolescent health outcomes. The objective of this study was to determine whether adolescent and parental adherence to components of an e-health intervention resulted in change in adolescent body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC) z-scores in a sample of overweight/obese adolescents.

Methods

In total, 159 overweight/obese adolescents and their parents participated in an 8-month e-health lifestyle intervention. Each week, adolescents and their parents were asked to login to their respective website and to monitor their dietary, physical activity, and sedentary behaviours. We examined participation (percentage of webpages viewed [adolescents]; number of weeks logged in [parents]) and self-monitoring (number of weeks behaviors were tracked) rates. Linear mixed models and multiple regressions were used to examine change in adolescent BMI and WC z-scores and predictors of adolescent participation and self-monitoring, respectively.

Results

Adolescents and parents completed 28% and 23%, respectively, of the online component of the intervention. Higher adolescent participation rate was associated with a decrease in the slope of BMI z-score but not with change in WC z-score. No association was found between self-monitoring rate and change in adolescent BMI or WC z-scores. Parent participation was not found to moderate the relationship between adolescent participation and weight outcomes.

Conclusions

Developing strategies for engaging and promoting supportive interactions between adolescents and parents are needed in the e-health context. Findings demonstrate that improving adolescents’ adherence to e-health lifestyle intervention can effectively alter the weight trajectory of overweight/obese adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Childhood obesity continues to be a worldwide epidemic [24, 41] and is associated with significant health issues, including metabolic, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, orthopedic, and psychological disorders, in adulthood [23]. Among Canadian youth, 31.1% are overweight or obese and 11.6% are obese [31]. Family-based interventions that target physical activity (PA), sedentary, and dietary behaviours have had some success at treating childhood obesity [19, 26]. However, there is a need to improve the efficacy of these interventions among adolescents as they have only demonstrated modest and short-term effects (on average, −0.14 change in body mass index (BMI) z-score at 12 months follow-up) [26].

Web-based or e-health interventions delivered through the internet are a potentially cost-effective and promising method for delivering adolescent weight management interventions as the majority of households (at least 83% of Canadian and U.S. households) have access to the internet [14, 34]. E-health interventions have been shown to be at least as effective as traditional non-web-based interventions [42] and evidence regarding their efficacy to treat or prevent childhood obesity is still emerging [10, 11, 15]. However, adherence (defined as attendance and utilization of intervention components) to e-health interventions varies greatly. In a systematic review of e-health interventions among adults, an average adherence rate of 50% was documented, with a wide range reported across studies (10 to 90%) [18, 34]. Adherence to lifestyle interventions has consistently predicted reduction in BMI z-score in children [13, 36] and recently has been identified as the single most important factor to target for increasing the success of such interventions [27].

E-health interventions often consist of several components (e.g., educational materials, self-monitoring, goal-setting, etc.) and the extent to which adherence to these components affect change in BMI among adolescents is unknown. In one study, adolescents who utilized more self-monitoring components of a lifestyle intervention (i.e., tracking food and beverage intake) achieved greater reductions in BMI z-score [32]. In contrast, other studies of adolescents found no change in BMI z-score with attendance and utilization of program components [28]. Parent participation in interventions can also affect adolescents’ adherence and result in greater weight loss [35, 38, 46]. For instance, when mothers regularly attended treatment sessions with their daughters in a 16-week behavioral weight control program for Black adolescent girls, daughters lost significantly more weight than when mothers did not attend the sessions [38]. Although several e-health weight management interventions for adolescents have involved parental participation, few have evaluated the effect of parental participation on adolescent adherence [1].

In summary, parental and child adherence appears important to improve the efficacy of pediatric weight management interventions. However, different components may have different effects on weight outcomes and the role of parental participation on adolescent adherence has not been well studied in the e-health context. Therefore, this study examined: 1) whether adolescent adherence to specific components of an e-health lifestyle modification intervention (participation and self-monitoring) predicted change in BMI and waist circumference (WC) z-scores and 2) whether parental participation and self-monitoring moderated the relationship between adolescent adherence and change in BMI and WC z-scores. It was hypothesized that adolescents who had higher participation and utilized more self-monitoring tools would have a greater reduction in BMI and WC z-scores compared to adolescents who had lower participation and utilized less self-monitoring tools. In addition, an even greater reduction in BMI and WC z-scores was expected among adolescents with a high participating parent compared with a low participating parent.

Methods

Sample

Adolescents and one corresponding parent were recruited through online and paper advertisements (68%), by mailing invitations to patients of the British Columbia (BC) Children’s Hospital Endocrinology and Diabetes Clinic (14%), previous participants of the Centre for Healthy Weights program in BC (14%) and by other sources (4%). Adolescents were eligible if they were between the ages of 11 and 16 years and overweight or obese (defined as >1 Standard Deviation (SD) for age and sex using the World Health Organization (WHO) cut-offs) [44]. The adolescent and their parent had to be living in the Metro Vancouver area, not planning to move during the study and be literate in English. Adolescents were excluded if they were diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, had other comorbidities requiring medical attention, had health problems or disabilities precluding them from being physically active, had a history of a diagnosed psychiatric condition or substance abuse, were enrolled in another behavioural change or weight loss intervention, or were using medications that affected body weight. One parent had to volunteer to participate in the study, the family self-selected which parent was able to attend all in-person assessments. Of the 454 parent-adolescent dyads that responded to the advertisements or invitations and were contacted, 227 declined and 51 did not meet the eligibility criteria. The remaining 176 (38.8%) families were invited to attend and completed the initial baseline assessment −16 dropped out after baseline assessment and were never briefed about the intervention and one family was excluded from the analyses due to a death within the family leaving 159 families included in the analyses.

Data collection protocol

This study was approved by the University of British Columbia Children’s and Women’s Research Ethics Board and by the University of Waterloo’s Research Ethics Board. Parent-adolescent dyads who met eligibility criteria and expressed interest in the study received the consent form via email and attended an in-person meeting at an evaluation centre. At the initial meeting, the parent-adolescent dyads reviewed and signed the consent forms and completed the baseline questionnaires. One to two weeks later, the dyads returned to the evaluation centre and were introduced to the MySteps® intervention, provided with login information, given pedometers to monitor their steps, and shown how to record and track their behaviours (steps, sedentary behaviours, and dietary intake). Parent-adolescent dyads were instructed to login every week for a period of eight months with new content being available every Sunday. Follow-up assessments were scheduled at 4- and 8-months, and all data were collected from December 2010 to March 2013.

Intervention

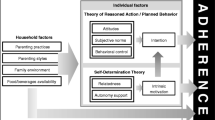

The intervention has been described elsewhere [20]. Briefly, the MySteps® intervention adapted the adolescent PACE e-health intervention [28, 29] to the Canadian context –aligning the intervention with the Canada Food Guide [16] and recommendation for PA [37]. MySteps® included individualized and familial web-based weight management information for adolescents and their parents based on the Chronic Care Model, [39]. Social Cognitive Theory, [5] and the Transtheoretical Model of Change [30]. From these perspectives, the MySteps intervention included motivational counseling via email and telephone contact, skill building techniques (including goal setting, self-monitoring, and social support techniques), tailored interactions, targeted known mediators of behavior change (self-efficacy, barriers, enjoyment, goal setting, and social support), and referral to community resources.

The 8-month (34 weeks) web-based intervention consisted of weekly logins to a website that encouraged healthy eating, PA, and reduced screen time. For the first 17 weeks, adolescents were expected to login on a weekly basis and received new topics, challenges, and skills to help them change their behaviours. The intervention started by assessing each adolescent’s current behaviours and then developing an action plan based on their initial behaviours. During the first 17 weeks, adolescents learn the benefits of improving their health behaviours and set behaviour change goals. In addition, the website allowed them to track their steps, diet, and screen time. For the remaining 17 weeks, adolescents were still expected to login on a weekly basis; however, they were allowed to choose the behaviours and skills they worked on. The parents were asked to login to a different website and each week they received complementary topics and challenges designed to support their child’s challenges of the week. Parents also received bi-weekly emails with information about how to help and encourage their adolescents to change their health behaviours and create a supportive environment. Both parents and adolescents were given a one-week break from logging in to the website, on week 23, but were encouraged to practice what they learned. Weekly reminders to login to the website were emailed to parents and adolescents. In addition, adolescents completed counselling sessions via telephone (5–10 min in duration) on weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16. Finally, both parents and adolescents were provided with pedometers at the start of the intervention to track their behaviors.

Measures

Participation rate

For adolescents, participation rate was defined as the mean percentage of webpages viewed per week, where a total of 83 and 78 pages could be viewed in the first and last 4-months, respectively (typically there were four to five pages per week to view). Parental participation rate was defined as the percentage of weeks the parents logged in to their website over the study period.

Self-monitoring

Parent and adolescent self-monitoring rates were defined as the number of weeks parents and adolescents, respectively, tracked either their diet (e.g., consumption of fruit and vegetables, fast foods, and sugar-sweetened beverages), steps, or TV/computer usage divided by the total number of weeks in the study period. The tracking tools were incorporated in the MySteps® and participants had access to the tracking tools as soon as they began the intervention and were prompted throughout the intervention to utilize them. In the first 16 weeks of the intervention they were prompted 11 times to use the internal tracking forms and for the remaining of the program tracking prompts depended on the behavior adolescent chose to work on. Participants needed to have recorded information on at least one of the three activities on at least one of the seven days of the week to be counted as having tracked (yes/no) that particular week.

Anthropometric measure

Height, weight, and WC were measured for adolescents and the corresponding parent at baseline, 4-months, and 8-months. Measurements were taken twice at each visit using a stadiometer (Hohltain, United Kingdom) for height, a calibrated scale (Model 597 K, Health-o-meter, McCook, Illinois) for weight, and a measuring tape (Hoechstmass, Germany) for WC. BMI (kg/m2) was determined by dividing the average weight (kg) with the average height (m) squared. BMI z-scores were derived from a Stata macro developed by the WHO for children and adolescents aged 5 to 19 (World Health Organization [45]). WHO cutoffs for overweight and obesity were used to describe the weight status of adolescents (>1 standard deviation (SD) = overweight; >2 SD = obesity) and parents (<18.5 as underweight, 18.5 to 24.9 as normal weight, 25 to 29.9 as overweight, and > = 30 as obese). WC z-scores were calculated using Canadian data [17].

Demographics

Age, gender, ethnicity, household income, and maternal education data were collected from parents at baseline using adapted questions from the Canadian Community Health Survey [33]. Parents were asked to select their cultural and racial background from a list of 13 ethnic categories. Responses were re-categorized to: 1) White; 2) Chinese/South East Asian; 3) South Asian; 4) Aboriginal; and 5) other. Maternal educational and household income were grouped into categories as displayed in Table 1.

Analysis

Linear mixed models were conducted to assess the effect of adolescent participation and self-monitoring rates on change in adolescent BMI and WC z-scores over time. Adolescent participation rate and self-monitoring were analyzed separately for the two outcome variables. Included in each model were time (as a random effect), an interaction between time and the main independent variable (participation rate or self-monitoring) controlling for all baseline socio-demographic variables (i.e., adolescent age and gender and household income, maternal education, and ethnicity). Linear mixed models allows for the inclusion of all available data regardless of the amount of missing data. Analyses of the data using multiple imputation techniques found similar results and therefore are not reported. The moderating effect of parent participation was examined by including all three-way and two-way interaction terms between parent participation, adolescent participation and time. Multivariable regression analyses were conducted to assess predictors of adolescent adherence and self-monitoring rates using all socio-demographic variables and parental participation and self-monitoring. All analyses were conducted using Stata v.13.1.

Results

Sample characteristics are displayed in Table 1. Of the adolescents, 81% were obese. In contrast, 34% of parents were overweight and 41% were obese. Of the 33 weeks that adolescents and parents were asked to login to their respective websites, adolescents logged into the website an average of 13.4 weeks, and parents logged into the website an average of 7.5 weeks (Table 2).

Table 2 displays the mean and median participation and self-monitoring rates of adolescents and parents. On average, adolescents and parents completed 28% (proportion of web-pages viewed) and 23% (proportion of weeks logged in) of the intervention, respectively. The participation rate was significantly higher during the first 4 months than the last 4 months for both adolescents (38% vs. 18%) and parents (31% vs. 14%). Fifteen (9.4%) adolescents and 50 parents (31.5%) did not login to the intervention website during the entire study period. On average, adolescents and parents entered self-monitoring data on at least one day for at least one behaviour for 24% and 13% of the weeks during the study period, respectively. Forty-one adolescents (26%) and 81 parents (51%) did not enter any self-monitoring information during the entire study period.

In multivariable regression analyses, parent adherence rate was significantly associated with adolescent participation rate such that a 10% increase in parent participation rate was associated with a 6.1% increase in adolescent participation rate (Table 3). Similarly, parent self-monitoring was significantly associated with adolescent self-monitoring such that a 10% increase in parent self-monitoring was associated with a 5.4% increase in adolescents self-monitoring.

Table 4 displays the results of the linear mixed models predicting change in BMI z-score and WC z-score. A significant time-by-participation rate interaction (p < 0.01) effect was found on BMI z-score such that adolescents with high levels of participation had a decreasing trajectory of BMI z-score and those with low levels of participation had a stable or increasing trajectory of BMI z-score. Differences in BMI z-score trajectory by participation rate can be found in Fig. 1. A decreasing trajectory started at participation rates greater than 10%. No other significant interaction effect was found among the other models. The inclusion of parent participation as an interaction term with adolescent participation and time was not significant and was therefore left out of the model.

Discussion

This study found that adolescents who had greater participation in the e-health lifestyle intervention had a greater decrease in their BMI z-score trajectory at 8-months than those who participated less. Specifically, adolescents who viewed more than 10% of the intervention materials stabilized their BMI z-score trajectories but those who viewed more content saw a greater decrease in their BMI z-score trajectories – e.g., viewing 50% of the content resulted in an average BMI z-score reduction of 0.1 at 8-months. This represents the first web-based intervention study among adolescents that documented a change in BMI z-score as previous studies found attendance or utilization of program components resulted in change in health behaviours (PA and nutrition outcomes) without a change in BMI z-score [15, 28, 43]. The short duration of previous e-Health interventions may explain why weight change was not observed in past studies [15]. In addition, parent participation did not appear to moderate the effect of adolescent participation on weight outcomes. Finally, counter to what others have found, [12, 21, 25, 28] utilization of the self-monitoring tools by either parents or adolescents was not related to adolescents’ change in BMI or WC z-scores. It may be that the self-monitoring tools utilized in this intervention were not as engaging as those included in other studies as a high percentage of adolescents and parents did not use them (26% and 51%, respectively).

Contrary to expectations, parental participation did not influence the outcomes of the intervention as it did not moderate adolescents change in BMI z-score even though parental participation was associated with adolescents’ participation. This finding contradicts what others have found as family-based intervention have improved the success of traditional clinical interventions [22, 26]. However, these interventions focused on pre-adolescents or younger children, targeted the parents, and were delivered in person and in group-based settings and ensured that parents were actively engaged in the intervention [3]. One possible mechanisms through which parental participation could have influenced the outcomes of the current intervention is by changing the home environment to better support their adolescent’s health behaviors, [11] as the parent site provided them with advice on how to support the challenges and goals their adolescents were expected to achieve that week. While this e-health intervention targeted both the adolescents and their parents, the e-health context may be less successful at engaging and promoting supportive interactions between adolescents and their parents. While parents can influence their adolescents’ participation in the intervention, the approach they use to achieve this may not result in the desired effect as observed in this study. For example, if parents are pressuring their adolescents to participate it can explain why parental participation did not influence the outcomes of the intervention as controlling strategies have been found to be less effective than autonomy supportive approaches in achieving desired health behaviours [7]. For example, a number of observational and longitudinal studies have shown that parents who use controlling practices such as pressuring the child to eat healthier food result in poor self-regulatory behaviours such as eating in the absence of hunger [8, 9]. Previous studies emphasize the importance of supporting change in children’s health behaviours at the household level; [3, 22] however, this study suggests the need in helping parents use more autonomy supportive parenting practices as it may explain why their engagement did not positively influence the outcome of the intervention. Future e-health interventions should better support parent/adolescent interactions, such as providing parents with the skills to use autonomy supportive approaches as a way to better support their adolescent and ultimately improve the efficacy of these interventions.

As internet access in households is becoming increasingly common (in 2012 at least 83% of Canadian and U.S., households had internet at home), [34] online delivery of interventions has the potential to broadly improve health outcomes among a wider segment of the population [2, 4, 6]. However, participation rates for online interventions have been quite variable [18]. Overall, participation in the present e-health intervention was sub-optimal for both adolescents and parents and appears much lower than other web-based interventions that report a 50% participation rate on average [18]. However, it is somewhat difficult to compare participation rates across studies as most use login rates versus percent of content viewed which is what was reported for the adolescents in the current study. The login rate for this study, defined as the number of weekly logins over the total number of weeks of the study, was 40.5% for the adolescents and 22.3% for the parents. In addition, participation rates are likely higher in shorter interventions than in longer interventions. In fact, this study found much higher participation rates in the first four months of the intervention than in the last four months. Nonetheless, strategies to improve participation of adolescents may benefit e-health interventions.

Utilization of the self-monitoring tools that were part of the e-health intervention was not found to have an effect on adolescents BMI z-score trajectory, even though there is evidence that such strategy is important to include in interventions [12, 21, 25, 28]. This study documented utilization of the self-monitoring tools by determining whether the participants entered information into the e-health program; however, both parents and adolescents could have used alternative ways of self-monitoring which was not captured by the e-health program (such as using the technique without actually entering the information in the program). This e-health program had different tracking forms for each behavior (steps, screen time, and dietary behaviours) and participants were not expected to use them every week. Perhaps using a single tracking form and setting the expectation that it be used every week would have had a different impact on the outcomes and can partly explain the findings and discrepancies with others studies [12, 21, 25, 28].

There are several limitations to this study. First, the sample included families with overweight and obese adolescents that volunteered to participate in the intervention limiting the generalizability to this population which is typical of similar studies. Second, adolescent’s participation measured whether they viewed the content but it could not be determined whether they fully read the content. Third, this study did not include a control group; therefore, the effect of the intervention on change in BMI z-score must be taken with caution. However, participants that had higher participation rates showed a greater reduction in BMI z-score indicating a potential effect from the intervention. Lastly, the study did not take into account self-perceived weight status which has been shown to be associated with intention to prevent weight gain [40].

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study found a dose-response relationship between adolescent participation to an e-health lifestyle intervention with BMI trajectory – finding a greater decrease in BMI z-score among overweight or obese adolescents with increased participation. Parental participation influenced their adolescents’ participation; however, it did not influence their adolescents’ reduction in BMI. Future interventions could benefit from exploring potential mechanisms to improve adherence of adolescents in e-health interventions. With improved adherence, these results suggest that e-health lifestyle interventions can be an effective strategy to beneficially alter the weight trajectory of overweight and obese adolescents. In addition, this study highlights the need to develop strategies that promote both active and supportive engagement of parents in e-health interventions as a way to further increase the efficacy of these interventions.

Abbreviations

- BC:

-

British Columbia

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Ajie WN, Chapman-Novakofski KM. Impact of computer-mediated, obesity-related nutrition education interventions for adolescents: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54:631–45.

Amstadter AB, Broman-Fulks J, Zinzow H, Ruggiero KJ, Cercone J. Internet-based interventions for traumatic stress-related mental health problems: a review and suggestion for future research. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:410–20.

An JY, Hayman LL, Park YS, Dusaj TK, Ayres CG. Web-based weight management programs for children and adolescents: a systematic review of randomized controlled trial studies. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2009;32:222–40.

Andersson G, Cuijpers P. Internet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38:196–205.

Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:143–64.

Barak A, Hen L, Boniel-Nissim M, Shapira N. A comprehensive review and a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of internet-based psychotherapeutic interventions. J Technol Hum Serv. 2008;26:109–60.

Baumrind D. Patterns of parental authority and adolescent autonomy. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2005:61–9.

Birch LL, Davison KK. Family environmental factors influencing the developing behavioral controls of food intake and childhood overweight. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2001;48:893–907.

Birch LL, Fisher JO, Davison KK. Learning to overeat: maternal use of restrictive feeding practices promotes girls' eating in the absence of hunger. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:215–20.

Chaplais E, Naughton G, Thivel D, Courteix D, Greene D. Smartphone interventions for weight treatment and behavioral change in pediatric obesity: a systematic review. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21:822–30.

Chen JL, Wilkosz ME. Efficacy of technology-based interventions for obesity prevention in adolescents: a systematic review. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2014;5:159–70.

DeBar LL, Stevens VJ, Perrin N, Wu P, Pearson J, Yarborough BJ, Dickerson J, Lynch F. A primary care-based, multicomponent lifestyle intervention for overweight adolescent females. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e611–20.

Denzer C, Reithofer E, Wabitsch M, Widhalm K. The outcome of childhood obesity management depends highly upon patient compliance. Eur J Pediatr. 2004;163:99–104.

File T, Ryan C, Computer Internet use in the United States. American community survey reports, ACS-28. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2013. https://www.census.gov/history/pdf/2013computeruse.pdf. Accessed: 12 Dec 2016

Hammersley ML, Jones RA, Okely AD. Parent-focused childhood and adolescent overweight and obesity ehealth interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J MedInternetRes. 2016;18:e203.

Health Canada. (2008) Canada's Food Guide. http://hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/food-guide-aliment/order-commander/index-eng.php. Accessed: 12 Dec 2016.

Katzmarzyk PT. Waist circumference percentiles for Canadian youth 11-18y of age. EurJClinNutr. 2004;58:1011–5.

Kelders SM, Kok RN, Ossebaard HC, Van Gemert-Pijnen JE. Persuasive system design does matter: a systematic review of adherence to web-based interventions. J Med InternetRes. 2012;14:e152.

Loveman E, Al-Khudairy L, Johnson RE, Robertson W, Colquitt JL, Mead EL, Ells LJ, Metzendorf MI, Rees K. Parent-only interventions for childhood overweight or obesity in children aged 5 to 11 years. CochraneDatabaseSystRev. 2015;12:CD012008.

Mâsse LC, Watts AW, Barr SI, Tu AW, Panagiotopoulos C, Geller J, Chanoine JP. Individual and household predictors of adolescents' adherence to a web-based intervention. AnnBehavMed. 2014;49:371–83.

Michie S, Abraham C, Whittington C, McAteer J, Gupta S. Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: a meta-regression. Health Psychol. 2009;28:690–701.

National Academies of Sciences, E. a. M. Parenting matters: supporting parents and children ages 0–8. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2016. doi:10.17226/21868.

Neef M, Weise S, Adler M, Sergeyev E, Dittrich K, Korner A, Kiess W. Health impact in children and adolescents. BestPractResClinEndocrinolMetab. 2013;27:229–38.

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, Mullany EC, Biryukov S, Abbafati C, Abera SF, Abraham JP, Abu-Rmeileh NM, Achoki T, AlBuhairan FS, Alemu ZA, Alfonso R, Ali MK, Ali R, Guzman NA, Ammar W, Anwari P, Banerjee A, Barquera S, Basu S, Bennett DA, Bhutta Z, Blore J, Cabral N, Nonato IC, Chang JC, Chowdhury R, Courville KJ, Criqui MH, Cundiff DK, Dabhadkar KC, Dandona L, Davis A, Dayama A, Dharmaratne SD, Ding EL, Durrani AM, Esteghamati A, Farzadfar F, Fay DF, Feigin VL, Flaxman A, Forouzanfar MH, Goto A, Green MA, Gupta R, Hafezi-Nejad N, Hankey GJ, Harewood HC, Havmoeller R, Hay S, Hernandez L, Husseini A, Idrisov BT, Ikeda N, Islami F, Jahangir E, Jassal SK, Jee SH, Jeffreys M, Jonas JB, Kabagambe EK, Khalifa SE, Kengne AP, Khader YS, Khang YH, Kim D, Kimokoti RW, Kinge JM, Kokubo Y, Kosen S, Kwan G, Lai T, Leinsalu M, Li Y, Liang X, Liu S, Logroscino G, Lotufo PA, Lu Y, Ma J, Mainoo NK, Mensah GA, Merriman TR, Mokdad AH, Moschandreas J, Naghavi M, Naheed A, Nand D, Narayan KM, Nelson EL, Neuhouser ML, Nisar MI, Ohkubo T, Oti SO, Pedroza A, Prabhakaran D, Roy N, Sampson U, Seo H, Sepanlou SG, Shibuya K, Shiri R, Shiue I, Singh GM, Singh JA, Skirbekk V, Stapelberg NJ, Sturua L, Sykes BL, Tobias M, Tran BX, Trasande L, Toyoshima H, Van DV, Vasankari TJ, Veerman JL, Velasquez-Melendez G, Vlassov VV, Vollset SE, Vos T, Wang C, Wang X, Weiderpass E, Werdecker A, Wright JL, Yang YC, Yatsuya H, Yoon J, Yoon SJ, Zhao Y, Zhou M, Zhu S, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Gakidou E. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–81.

Olander EK, Fletcher H, Williams S, Atkinson L, Turner A, French DP. What are the most effective techniques in changing obese individuals' physical activity self-efficacy and behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J BehavNutrPhysAct. 2013;10:29.

Oude LH, Baur L, Jansen H, Shrewsbury VA, O'Malley C, Stolk RP, Summerbell CD. Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD001872.

Pagoto SL, Appelhans BM. A call for an end to the diet debates. J Am Med Assoc. 2013;310:687–8.

Patrick K, Calfas KJ, Norman GJ, Zabinski MF, Sallis JF, Rupp J, Covin J, Cella J. Randomized controlled trial of a primary care and home-based intervention for physical activity and nutrition behaviors: PACE+ for adolescents. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2006;160:128–36.

Patrick K, Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, Lydston DD, Calfas KJ, Zabinski MF, Wilfley DE, Saelens BE, Brown DR. A multicomponent program for nutrition and physical activity change in primary care: PACE+ for adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:940–6.

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Rossi JS, Goldstein MG, Marcus BH, Rakowski W, Fiore C, Harlow LL, Redding CA, Rosenbloom D. Stages of change and decisional balance for 12 problem behaviors. Health Psychol. 1994;13:39–46.

Roberts KC, Shields M, de Groh M, Aziz A, Gilbert JA. Overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: results from the 2009 to 2011 Canadian health measures survey. Health Rep. 2012;23:37–41.

Saelens BE, McGrath AM. Self-monitoring adherence and adolescent weight control efficacy. Children's Health Care. 2003;32:137–52.

Statistics Canada. (2008) Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) Cycle 4.1. - 2007. http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Instr.pl?Function=getInstrumentList&Item_Id=33186&UL=1V&. Accessed 12 Dec 2016.

Statistics Canada. Canadian internet use survey, 2012. The Daily November 26, 2013. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/131126/dq131126d-eng.htm. Accessed 12 Dec 2016.

Steele MM, Steele RG, Hunter HL. Family adherence as a predictor of child outcome in an intervention for pediatric obesity: different outcomes for self-report and objective measures. Children's Health Care. 2009;38:64–75.

Summerbell CD, Ashton V, Campbell KJ, Edmunds L, Kelly S, Waters E. Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(3). Art. No: CD001872. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001872.

Tremblay MS, Warburton DE, Janssen I, Paterson DH, Latimer AE, Rhodes RE, Kho ME, Hicks A, Leblanc AG, Zehr L, Murumets K, Duggan M. New Canadian physical activity guidelines. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011;36:36–46.

Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ, Rich L, Rubin CJ, Sweidel G, McKinney S. Obesity in black adolescent girls: a controlled clinical trial of treatment by diet, behavior modification, and parental support. Pediatrics. 1990;85:345–52.

Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff(Millwood). 2001;20:64–78.

Wammes B, Kremers S, Breedveld B, Brug J. Correlates of motivation to prevent weight gain: a cross sectional survey. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2005;2:1.

Wang Y, Lim H. The global childhood obesity epidemic and the association between socio-economic status and childhood obesity. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2012;24:176–88.

Wantland DJ, Portillo CJ, Holzemer WL, Slaughter R, McGhee EM. The effectiveness of web-based vs. non-web-based interventions: a meta-analysis of behavioral change outcomes. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e40.

Whittemore R, Jeon S, Grey M. An internet obesity prevention program for adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:439–47.

World Health Organization. WHO Anthro (version 3.2.2, January 2011) and macros. Geneva, Switzerland; 2011. http://www.who.int/growthref/en. Accessed: 12 Dec 2016.

World Health Organization. Growth reference data for 5–19 years. Geneva, Switzerland; 2007. http://www.who.int/childgrowth/software/en. Accessed: 12 Dec 2016.

Xanthopoulos MS, Moore RH, Wadden TA, Bishop-Gilyard CT, Gehrman CA, Berkowitz RI. The association between weight loss in caregivers and adolescents in a treatment trial of adolescents with obesity. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38:766–74.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Maria Valente and Judith de Niet for helping collect the data for this study.

Funding

The data collection for this study was funded by a peer-reviewed grant that LCM received from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Institute (CIHR) of Nutrition, Metabolism and Diabetes and the Health Research Foundation (Funding Reference Number 92369). In addition, during the period of the study, LCM received salary support from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and the BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute (BCCHRI). AWW received a doctoral scholarship from CIHR in partnership with the Danone Institute of Canada, and from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and the CIHR Training Grant in Population Intervention for Chronic Disease Prevention: A Pan-Canadian Program (Grant #53893). AWT received a scholarship from a CIHR Doctoral Research Award and post-doctoral support from BCCHR and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Availability of data and materials

The de-identified datasets analyzed in this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

AWT analysed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. AWW collected and interpreted the data and edited the manuscript. JPC, CP, JG, RB, and SIB conceived the study and edited the manuscript. LCM obtained funding, conceived the study, interpreted the data, and edited the manuscript. Each author contributed to further development and revisions of the manuscript and approved the final submission.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the University of British Columbia Children’s and Women’s Research Ethics Board and by the University of Waterloo’s Research Ethics Board. At the initial meeting, families reviewed and signed the consent forms.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tu, A.W., Watts, A.W., Chanoine, JP. et al. Does parental and adolescent participation in an e-health lifestyle modification intervention improve weight outcomes?. BMC Public Health 17, 352 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4220-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4220-0