Abstract

Background

The consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) may contribute to the development of overweight among children. The present study aimed to evaluate associations between family and home-related factors and children’s SSB consumption. We explored associations within ethnic background of the child.

Methods

Cross-sectional data from the population-based ‘Water Campaign’ study were used. Parents (n = 644) of primary school children (6-13 years) completed a questionnaire on socio-demographic characteristics, family and home-related factors and child’s SSB intake. The family and home-related factors under study were: cognitive variables (e.g. parental attitude, subjective norm), environmental variables (e.g. availability of SSB, parenting practices), and habitual variables (e.g. habit strength, taste preference). Regression analyses were used to evaluate the associations between family and home-related factors and child’s SSB intake (p < 0.05).

Results

Mean age of the children was 9.4 years (SD: 1.8) and 54.1% were girls. The child’s average SSB intake was 0.9 litres (SD: 0.6) per day. Child’s age, parents’ subjective norm, parenting practices, and parental modelling were positively associated with the child’s SSB intake. The availability of SSB at home and school and parental attitude were negatively associated with the child’s SSB intake. The associations under study differed according to the child’s ethnic background, with the explained variance of the full models ranging from 8.7% for children from Moroccan or Turkish ethnic background to 44.4% for children with Dutch ethnic background.

Conclusions

Our results provide support for interventions targeting children’s SSB intake focussing on the identified family and home-related factors, with active participation of parents. Also, the relationships between these factors and the child’s SSB intake differed for children with distinct ethnic backgrounds. Therefore, we would recommend to tailor interventions taking into account the ethnic background of the family.

Trial registration

Number NTR3400; date April 4th 2012; retrospectively registered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) among primary school children has been found to be positively associated with obesity and other health problems later in life [1–6]. To increase the effectiveness of interventions aiming to decrease children’s SSB intake, it is necessary to identify the factors underlying their SSB consumption [7–9].

Cognitive models [10, 11] assist in providing an understanding of how behaviours such as SSB consumption develop as a result of cognitive factors such as attitude (i.e. behavioural beliefs), subjective norm (i.e. perceived social pressure) and perceived behavioural control (i.e. perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behaviour) [12, 13]. However, combined behavioural and environmental models like for instance the Environmental Research framework for weight Gain prevention (EnRG-framework) [14], indicate that physical or social environmental factors also influence health behaviours [15–18]. Parents, and consequently the home environment, play an essential role in establishing healthy behaviours for children [19–22]. Therefore, factors of interest include availability and accessibility of SSB at home, food rules and parenting practices (i.e. specific behaviours that parents use while/to raising their children), as well as parental involvement and role modelling [22, 23]. Additionally, it has been argued that habit strength (i.e. how strong a learned behavioural response is to a situational cue) and taste preferences (i.e. liking one food over another) are considered important factors to understand health behaviours [24–26]. Thus far, studies have yielded mixed results with regard to the associations between family and home-related factors and the child’s SSB consumption [23, 27–36].

Overweight prevalence between children with certain ethnic backgrounds differs [37–40]. Consequently, awareness has been raised about potential differences regarding factors determining the child’s SSB intake among families and children with different ethnic backgrounds [41–43]. More specifically, eating culture and parenting styles differ for families with diverse ethnic backgrounds [44, 45]. In addition, previous research shows that families from different ethnic minority groups may live in more (or less) obesogenic home environments, which subsequently may influence their healthy and unhealthy behaviours with respect to other demographic groups [46–50]. Brug and colleagues described that eating culture in relation to the child’s food environment differs across countries in Europe and that it is recommended to implement different strategies to improve healthy behaviours among children [43]. For instance, a study found that Dutch children consumed the most SSB compared to other European countries and that the SSB consumption of children living in countries with less SSB-friendly environments was lower [40].

Studies specifically focussing on evaluating the association between ethnic background (within one region) and family and home-related factors are lacking [46, 47], and non-existing within the Dutch multi-ethnic setting within the larger cities. According to Wyse and colleagues, their research among Australian preschool children showed the social-cultural environment (e.g. family eating patterns) as the most amendable to intervene [51]. Deepening our understanding of the associations within different ethnic groups will improve the ability to develop culturally appropriate interventions [52]. Based on their systematic review, Gubbels and colleagues emphasize that the next step within lifestyle research should be to differentiate and tailor interventions according to moderating factors described in the EnRG-framework to enhance interventions’ effectiveness [53].

Therefore, insights into and understanding of the associations between family and home-related factors with child’s health behaviour within different ethnic groups may contribute to the development of these interventions tailored to specific subgroups. In this study, the objective was to first study associations between family and home-related factors with child’s SSB intake and second, to explore these associations within different ethnic groups. Our hypothesis was: the associations between family and home-related factors with child’s SSB intake are different within distinct ethnic groups.

Methods

Study population and procedure

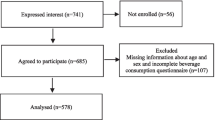

Our cross-sectional study used data from the population-based ‘Water Campaign’ study [54]. This controlled trial assessed the effects of a combined school- and community-based intervention on children’s SSB consumption. The Medical and Ethical Review Committee of the Erasmus Medical Centre issued a ‘declaration of no objection’ (i.e. formal waver) for this study (reference number MEC-2011-183). Four primary schools located in multi-ethnic neighbourhoods in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, were included in the study; two schools were included as intervention schools, two schools were included as control schools. Intervention and control schools were matched on number of pupils, socio-economic status and overweight prevalence. The included schools resulted from a convenience sample of schools participating in a municipal overweight intervention program. Only schools in disadvantaged neighbourhoods were eligible for this intervention [54].

All children of grades 2 to 8 (aged 6 to 13 years) within each of the four included schools were invited to participate, resulting in a total of 1288 invited children. Passive parental consent was obtained. Parents (and children) received a brochure with information to notify and inform them about the intervention and study participation. The study was also announced by the school, via the school letter and through the teachers and by flyers which were visible throughout the school. Parents (and children) were free to refuse participation without giving any explanation. They could do so by informing one of the teachers at their school or one of the researchers when present at school. At all times, the researchers could be contacted by a special phone-number or e-mail, for instance to decline participation [54]. Measurements were performed at baseline and after one year, using questionnaires (child and parental) and observations at school.

For the present study, data from the baseline parental questionnaire (administered March/April 2011) was used. A study population of 644 children (6 to 13 years) was available for analyses.

Measures

Socio-demographic characteristics child and parent

The child’s gender (boy/girl), age (years), and ethnic background were assessed. Ethnic background was defined by country of birth of the parents according to definitions given by Statistics Netherlands [55]. The child’s ethnic background was defined as Dutch only if both parents had been born in the Netherlands; if one of the parents had been born in another country, ethnic background was defined according to that country; and if both parents had been born in different foreign countries, ethnic background was defined as the mother’s country of birth. Ethnic background was categorized as ‘Dutch’; ‘Surinamese/Antillean’; ‘Moroccan/Turkish’; or ‘other/unknown’.

Respondents were either the father or the mother of the child, and parental gender was based on this item (male/female). From this point onwards, respondent is described as ‘parent’. Parental age (years) and educational level were also reported. Based on standard Dutch cut-off points, parents’ highest achieved educational level was categorized as ‘low’ (no education; primary school; ≤3 years of general secondary school); ‘mid-low’ (>3 years of general secondary school); ‘mid-high’ (higher vocational training; undergraduate programs); or ‘high’ (higher academic education) [56].

In addition to the parental questionnaire, weight and height of the child were obtained by trained personnel. Weight status was determined by calculating BMI in kg/m2 with height measured to the nearest 0.1 cm and weight measured to the nearest 0.2 kg, in light clothing or gym clothes, according to a national standardized protocol for Youth Health Care [57]. Children were categorized as being either ‘non-overweight’ or ‘overweight/obese’, based on cut-off points published by the International Obesity Task Force [58].

Family and home-related factors

Additional file 1: Table S1 provides an overview of the scales (and items) that were used to measure the family and home-related factors: (a) cognitive variables, (b) environmental variables, and (c) habitual variables. The measures of the cognitive variables and the environmental variables were based on the studies ‘ENDORSE’ and ‘Be Active, Eat Right’ [59, 60]. They were developed using the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) as proposed by Ajzen [10]. The items were tailored to the consumption of SSB by children as suggested by Oluka et al. [61] and by Francis et al. [62]. The items used to measure the construct ‘habit’ were derived from the Self-Report Behavioural Automaticity index [63, 64].

In Additional file 1: Table S1 we report the percentages of missing answers per item and per scale as indicator of the feasibility of the measurements in our study. Scales were only computed when there were no missing data on any of the items. Additional file 1: Table S1 also shows the Cronbach’s alpha per scale to assess the internal consistency of each multi-item scale.

The cognitive variables assessed were parental attitude towards the child’s SSB consumption (two items, Cronbach’s α = 0.84), parental attitude towards decreasing the child’s SSB consumption (four items, Cronbach’s α = 0.70), parents’ subjective norm towards the child’s SSB consumption (one item), and the perceived behavioural control of parents towards having their child drink less SSB (two items, Cronbach’s α = 0.75). The percentage of missing values ranges from 2.6% to 7.6%; the internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s alpha is ≥0.7 for two multi-item scales and >0.8 for one scale (all scales show ‘good’ internal consistency [65]).

The environmental variables assessed included the availability of SSB at home and school (two items, Cronbach’s α = 0.64), parenting practices towards the child’s SSB intake (four items, Cronbach’s α = 0.74), rules at home with regard to the child’s SSB intake (two items, Cronbach’s α = 0.77), and modelling of SSB consumption by the parents (one single item; and a two items-scale, Cronbach’s α = 0.72). The percentage of missing values ranges from 2.3% to 6.2%; the internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s alpha is >0.7 for three of the multi-item scales (which is considered ‘good’), and >0.6 for one scale (which is considered ‘moderate’ [65]).

The habitual variables assessed were habit strength of the child’s SSB intake (four items, Cronbach’s α = 0.76) and taste preference of the child towards SSB (one item). The percentage of missing values ranges from 1.6% to 4.7%; the internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s alpha is >0.7 for the multi-item scale (which is considered ‘good’ [65]).

All items measuring the family and home-related factors were assessed by using a five-point response scale, except for the questions regarding restriction rules for the child’s SSB consumption (response scale ‘yes’/‘no’). All items were coded such that a higher score indicated more unfavourable behaviour (i.e. the child was expected to consume more SSB). The internal consistency of the multi-item scales was overall ‘moderate’ to ‘good’ (Cronbach’s α > 0.60) [65, 66]. The relatively low number of missing values supports the feasibility of the measures. We recommend further research regarding the validity of these measurement instruments in diverse populations.

SSB consumption

The following definition of SSB was used: beverages containing added sugar, sweetened dairy products (e.g. chocolate milk), fruit juices (e.g. apple juice), soft drinks (e.g. cola) and energy drinks (e.g. sport energy drinks). Examples of SSB were provided along with the question based on our definition of SSB.

Average SSB consumption was assessed using the question ‘On a day your child drinks SSB, how many glasses (250 ml), cans (330 ml) or bottles (500 ml) does your child consume on average?’. Response categories ranged from ‘none’ to ‘5 or more’. The child’s average SSB intake in litre per day was calculated by multiplying each reported glass, can and/or bottle with its volume and summed up thereafter.

Statistical analysis

Child and parental characteristics were analysed using descriptive statistics. Linear regression models were fitted. The dependent variable was the child’s average SSB intake in litre per day. The family and home-related factors (cognitive, environmental and habitual variables) of SSB consumption were used as independent variables in the model.

The independent variables were entered in the model as blocks, correcting for other variables within this block. The first block that was entered in the model contained the socio-demographic characteristics (child’s age, gender and ethnic background, and parental educational level); the second block contained the cognitive variables (parental attitude, parents’ subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control); the third block contained the environmental variables (availability, parenting practices, rules, and parental modelling); and the fourth and final block contained the habitual variables (habit strength and child’s taste preference). Finally, a full model was fitted with all independent variables. Beta’s with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were estimated. The (adjusted) R square is presented to indicate the estimated amount of explained variance for each model. Results were considered significant at p < 0.05 [66].

To explore differences in family and home-related factors according to ethnic background of the child, an interaction term was added to the model. Separately per block of variables (cognitive, environmental, and habitual) an interaction between ethnic background and the variable of interest was analysed, the model being only corrected for the variables in that block and not for any other (socio-demographic) variables. All interaction analyses are presented in Additional file 2: Table S2; several interactions differed statistically (p < 0.10) [66]. Therefore, the previously mentioned full model was fitted separately for the subgroups of children with a Dutch, Surinamese/Antillean, Moroccan/Turkish, and other/unknown ethnic background.

Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Study population characteristics

Mean age of the children was 9.4 years (SD: 1.8), 54.1% were girls, 30.3% were Dutch and 23.0% were overweight or obese. Parents’ mean age was 37.0 years (SD: 8.9), 87.4% were female and 18.5% indicated to have completed a high level of education. According to the parents, the average SSB intake of the children was 0.9 litres per day (SD: 0.6) per day (Table 1).

Table 1 also shows the differences in socio-demographic variables and child’s SSB intake for children from different ethnic backgrounds. For instance, differences were found between children with a Dutch ethnic background and children with a Surinamese or Antillean ethnic background with regard to average SSB intake: 0.7 litres per day (SD: 0.4) for Dutch children vs. 1.1 litres per day (SD: 0.9) for Surinamese or Antillean children (p < 0.05).

Associations related to the child’s SSB intake

Table 2 presents the results of the regression analyses evaluating the full model. The explained variance of the full model was 25.9% of the child’s SSB intake.

Child’s SSB intake associations according to ethnic background of the child

Presented in Table 3 are the full models of the child’s average SSB intake in litre per day separately for the four subgroups based on ethnic background. The explained variance of the full models ranged from 8.7% for children from Moroccan or Turkish ethnic background to 44.4% for children with a Dutch ethnic background.

The results are reported in accordance with STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) [67].

Discussion

In this paper, we evaluated associations between family and home-related factors and children’s SSB intake. Overall, child’s age, parental attitude, parents’ subjective norm, the availability of SSB at home and school, parenting practices and parental modelling showed to be associated with child’s average SSB intake in litre per day. Associations between family and home-related factors and child’s SSB intake differed for children with a Dutch, Surinamese/Antillean, Moroccan/Turkish, and other/unknown background.

In line with previous studies among children of similar age, we observed that children of parents who have a more positive attitude towards decreasing the child’s SSB intake or children of parents with a more positive subjective norm towards their child’s SSB intake, consumed less SSB [24, 28, 31, 59]. Also, children of parents who express healthier parenting practices towards the child’s SSB intake (i.e. more restrictive towards the child’s SSB consumption) and children of parents who less often model SSB consumption , are reported to have a lower SSB intake [18, 34, 41, 68, 69].

Contrary to other studies, we found that children consume less SSB when there is more SSB available in the home or school environment [29, 31, 33, 69]. This contradiction could be due to the cross-sectional nature of our study; children who already have high consumption levels might have less SSB available, following already implemented restrictions of their parents trying to improve the child’s lifestyle.

The significant positive associations between parenting practices and parental modelling and the child’s SSB consumption, emphasize the important role of parents in shaping the child’s dietary habits [17, 20, 21, 33, 34, 52, 68]. Parents serve both as role model and as facilitator impacting children’s consumption diet. To increase interventions’ effectiveness, parents should be involved or specifically targeted as intervention participants [22, 36, 43, 68].

In this paper, we explored whether the associations between the family and home-related factors under study and the child’s SSB intake differed according to ethnic background of the child. As Verzeletti emphasized, ethnic background differences may have an impact on parental beliefs regarding the child’s SSB consumption or on rules restricting the intake of SSB by the child [41]. Our results provide support for this statement.

Children with a Dutch ethnic background showed positive associations between the child’s SSB intake and parental attitude, parenting practices and parental modelling. Contrary to the model for all children together, our findings suggest that habit strength is an important determinant (only) for children with a Dutch ethnic background. Our model explained the most (44%) of the child’s SSB intake for children with a Dutch ethnic background.

For children with a Surinamese or Antillean ethnic background, parental attitude towards decreasing the child’s SSB intake was the only determinant that showed a significant association with the child’s SSB consumption; the model explained almost 28% of the child’s SSB consumption. We recommend future studies to explore factors that better explain the child’s SSB consumption among this specific group. In the meantime, in order to decrease the child’s SSB intake, special attention should be given to parental attitude when targeting children from Surinamese or Antillean ethnic background. For instance, health education as intervention element may be suggested as an element to change attitudes among these families [70].

Our model could explain just 9% of the child’s SSB intake for children with a Turkish or Moroccan ethnic background. Given this small percentage of explained variance, we recommend future research to further explore and identify factors associated with child’s SSB consumption. The two significant associations of factors with SSB consumption among Turkish or Moroccan children that were observed in the model appeared to be in the home environment (e.g. availability and modelling). Our results suggest that for children with a Turkish or Moroccan ethnic background, intervening on family level may be beneficial in order to reduce SSB consumption and not only improve the child’s lifestyle but also that of the family. Especially with regard to the availability of SSB, the family (e.g. parents) are responsible for buying SSB and determine to what extent SSB is provided to their child. Also parents’ modelling behaviour could be addressed in these family level interventions, for instance by including skills training and role play in the intervention [70].

For children with an ‘other or unknown’ ethnic background, the model explained almost 25%. However, interpretation of the results is difficult because of the varied composition of children in this group. It included for example children with non-Western (e.g. Afghanistan) and Western background (e.g. Germany). We have no explanation for the association between child’s age, parents’ subjective norm and rules at home and the child’s SSB intake.

Our results provide support for differences in the association between family and home-related factors and the child’s SSB intake according to the ethnic background of the child. Further research is needed to increase our understanding of these differences. It has been suggested that associations between demographic factors and health-related behaviours as were found in this study, might be due to differences in health literacy [71]. How well people understand and can act on health-related information has shown to be associated with healthy lifestyles [72]. Caregiver’s health literacy has been associated with their own and their children’s’ health outcomes [73–77]. Increased understanding of these factors and underlying mechanisms that possibly can explain the children’s lifestyle behaviours between subgroups could assist to further tailor and improve interventions, in order to enhance interventions’ effectiveness.

Methodological considerations

Evaluating the child’s SSB intake by means of a continuous measure, average consumption in litre per day is considered a strength of this study. Because of the possibility of information loss, using a continuous measure is preferred above transforming the measure into a dichotomous variable. However, seen by other studies, SSB intake is often reported dichotomously as ≤2 vs >2 SSB servings per day. When conducting the analyses with child’s intake in ≤2 vs >2 SSB servings per day as outcome measure, we observed similar associations between family and home-related factors and child’s SSB intake (both for the overall analyses as when exploring between children with different ethnic backgrounds; see Additional file 3: Tables S3-S6). The diverse population with children from various ethnic backgrounds and a response of 54.8% on the parent questionnaire (given the diverse population) are also strengths that have to be mentioned.

However, some limitations of the present study need to be addressed. We relied on parental self-reports, which is a commonly used way to assess children’s intake. Though there is a possibility that parents may have provided socially desirable answers, parent reports are seen as one of the most accurate methods to estimate a child’s intake (in the ages 4 to 11 years old) [78]. Children’s weight and height were measured by trained health professionals, applying a standardised protocol for Youth Health Care [57]. The measurements of family and home-related factors were based on the TPB and tailored to the consumption of SSB by children, as suggested by Oluka et al. [61] and Francis et al. [62]. In our study, the Cronbach’s alphas indicate ‘moderate’ to ‘good’ reliability of the multi-item scales. We recommend further research regarding the validity of these measurement instruments in multi-ethnic populations. Given the cross-sectional design of our study, inferences regarding cause and effect are not possible. It is recommended to explore and test our findings for causal inferences in longitudinal or experimental intervention studies. Also, the study was conducted in multi-ethnic inner-city neighbourhoods. The generalizability of our study findings might therefore be limited to children belonging to similar populations and settings.

Conclusions

This paper provided insight into factors related to children’s SSB consumption. We observed that the child’s age, parental attitude, parents’ subjective norm, the availability of SSB at home and school, parenting practices, parental modelling were associated with the child’s SSB consumption (in litre per day). These findings provide support for interventions to focus on parents and improve their (family) lifestyle in order to promote the transference of healthy behaviours to the children.

Moreover, we observed differences with respect to the associations between family and home-related factors and child’s SSB consumption for children with a Dutch, Surinamese/Antillean, Moroccan/Turkish, and other/unknown background. Therefore, further understanding of the factors of health behaviour of different target segments should be endorsed, through observational, qualitative research and quantitative research as well as longitudinal studies replicating our findings. By identifying the most important factors per target segment intervention effectiveness may be improved. In the meantime, we recommend intervention developers and behaviour change agents in the field to take relevant differences into account when developing tailored interventions within multi-ethnic communities.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- EnRG-framework:

-

Environmental Research framework for weight Gain prevention

- SSB:

-

sugar-sweetened beverages

- TPB:

-

Theory of Planned Behaviour

References

Ludwig DS, Peterson KE, Gortmaker SL. Relation between consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks and childhood obesity: a prospective, observational analysis. Lancet. 2001;357(9255):505–8.

Olsen NJ, Heitmann BL. Intake of calorically sweetened beverages and obesity. Obes Rev. 2009;10(1):68–75.

Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(4):667–75.

de Ruyter JC, Olthof MR, Seidell JC, Katan MB. A trial of sugar-free or sugar-sweetened beverages and body weight in children. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(15):1397–406.

Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(4):1084–102.

Wang M, Yu M, Fang L, Hu RY. Association between sugar-sweetened beverages and type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig. 2015;6(3):360–6.

Baranowski T. Handbook of health behavior research I: personal and social determinants. New York: Plenum Press; 1997.

Baranowski T, Cullen KW, Nicklas T, Thompson D, Baranowski J. Are current health behavioral change models helpful in guiding prevention of weight gain efforts? Obes Res. 2003;11(Suppl):23S–43S.

Glanz KRBLF. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy. The exercise of control. New York: Freeman; 1997.

Kassem NO, Lee JW. Understanding soft drink consumption among male adolescents using the theory of planned behavior. J Behav Med. 2004;27(3):273–96.

Kassem NO, Lee JW, Modeste NN, Johnston PK. Understanding soft drink consumption among female adolescents using the Theory of Planned Behavior. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(3):278–91.

Kremers SP, de Bruijn GJ, Visscher TL, van Mechelen W, de Vries NK, Brug J. Environmental influences on energy balance-related behaviors: a dual-process view. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3:9.

Egger G, Swinburn B. An “ecological” approach to the obesity pandemic. BMJ. 1997;315(7106):477–80.

Brug J, van Lenthe FJ, Kremers SP. Revisiting Kurt Lewin: how to gain insight into environmental correlates of obesogenic behaviors. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(6):525–9.

van der Horst K, Oenema A, Ferreira I, Wendel-Vos W, Giskes K, van Lenthe F, Brug J. A systematic review of environmental correlates of obesity-related dietary behaviors in youth. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(2):203–26.

Verloigne M, Van Lippevelde W, Maes L, Brug J, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Family- and school-based correlates of energy balance-related behaviours in 10-12-year-old children: a systematic review within the ENERGY (EuropeaN Energy balance Research to prevent excessive weight Gain among Youth) project. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(8):1380–95.

Birch LL, Fisher JO. Development of eating behaviors among children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101(3 Pt 2):539–49.

Golan M, Crow S. Parents are key players in the prevention and treatment of weight-related problems. Nutr Rev. 2004;62(1):39–50.

Rosenkranz RR, Dzewaltowski DA. Model of the home food environment pertaining to childhood obesity. Nutr Rev. 2008;66(3):123–40.

De Craemer M, De Decker E, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Vereecken C, Deforche B, Manios Y, Cardon G, ToyBox-study g. Correlates of energy balance-related behaviours in preschool children: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2012;13 Suppl 1:13–28.

Bere E, Glomnes ES, te Velde SJ, Klepp KI. Determinants of adolescents’ soft drink consumption. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(1):49–56.

Grimm GC, Harnack L, Story M. Factors associated with soft drink consumption in school-aged children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(8):1244–9.

Aarts H, Paulussen T, Schaalma H. Physical exercise habit: on the conceptualization and formation of habitual health behaviours. Health Educ Res. 1997;12(3):363–74.

van der Horst K, Kremers S, Ferreira I, Singh A, Oenema A, Brug J. Perceived parenting style and practices and the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages by adolescents. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(2):295–304.

Haerens L, Craeynest M, Deforche B, Maes L, Cardon G, De Bourdeaudhuij I. The contribution of psychosocial and home environmental factors in explaining eating behaviours in adolescents. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62(1):51–9.

de Bruijn GJ, Kremers SP, de Vries H, van Mechelen W, Brug J. Associations of social-environmental and individual-level factors with adolescent soft drink consumption: results from the SMILE study. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(2):227–37.

Verloigne M, Van Lippevelde W, Maes L, Brug J, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Family- and school-based predictors of energy balance-related behaviours in children: a 6-year longitudinal study. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(2):202–11.

Tak NI, Te Velde SJ, Oenema A, Van der Horst K, Timperio A, Crawford D, Brug J. The association between home environmental variables and soft drink consumption among adolescents. Exploration of mediation by individual cognitions and habit strength. Appetite. 2011;56(2):503–10.

Ezendam NP, Evans AE, Stigler MH, Brug J, Oenema A. Cognitive and home environmental predictors of change in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among adolescents. Br J Nutr. 2010;103(5):768–74.

Vagstrand K, Linne Y, Karlsson J, Elfhag K, Lindroos AK. Correlates of soft drink and fruit juice consumption among Swedish adolescents. Br J Nutr. 2009;101(10):1541–8.

Van Lippevelde W, te Velde SJ, Verloigne M, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Manios Y, Bere E, Jan N, Fernandez-Alvira JM, Chinapaw MJ, Bringolf-Isler B, et al. Associations between home- and family-related factors and fruit juice and soft drink intake among 10- to 12-year old children. The ENERGY project Appetite. 2013;61(1):59–65.

De Coen V, Vansteelandt S, Maes L, Huybrechts I, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Vereecken C. Parental socioeconomic status and soft drink consumption of the child. The mediating proportion of parenting practices. Appetite. 2012;59(1):76–80.

Vereecken CA, Inchley J, Subramanian SV, Hublet A, Maes L. The relative influence of individual and contextual socio-economic status on consumption of fruit and soft drinks among adolescents in Europe. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15(3):224–32.

Mazarello Paes V, Hesketh K, O’Malley C, Moore H, Summerbell C, Griffin S, van Sluijs EMF, Ong KK, Lakshman R. Determinants of sugar-sweetened beverages in young children: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2015;16:903–13.

Schonbeck Y, Talma H, van Dommelen P, Bakker B, Buitendijk SE, Hirasing RA, van Buuren S. Increase in prevalence of overweight in Dutch children and adolescents: a comparison of nationwide growth studies in 1980, 1997 and 2009. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2011;6(11):e27608.

van Dommelen P, Schonbeck Y, van Buuren S, Hirasing RA. Trends in a life threatening condition: morbid obesity in dutch, Turkish and moroccan children in the Netherlands. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2014;9(4):e94299.

Fredriks AM, Van Buuren S, Sing RA, Wit JM, Verloove-Vanhorick SP. Alarming prevalences of overweight and obesity for children of Turkish, Moroccan and Dutch origin in The Netherlands according to international standards. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94(4):496–8.

Brug J, van Stralen MM, Te Velde SJ, Chinapaw MJ, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Lien N, Bere E, Maskini V, Singh AS, Maes L, et al. Differences in weight status and energy-balance related behaviors among schoolchildren across Europe: the ENERGY-project. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2012;7(4):e34742.

Verzeletti C, Maes L, Santinello M, Vereecken CA. Soft drink consumption in adolescence: associations with food-related lifestyles and family rules in Belgium Flanders and the Veneto Region of Italy. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20(3):312–7.

van der Horst K, Oenema A, te Velde SJ, Brug J. Gender, ethnic and school type differences in overweight and energy balance-related behaviours among Dutch adolescents. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2009;4(4):371–80.

te Velde SJ, Singh A, Chinapaw M, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Jan N, Kovacs E, Bere E, Vik FN, Bringolf-Isler B, Manios Y, et al. Energy balance related behaviour: personal, home- and friend-related factors among schoolchildren in Europe studied in the ENERGY-project. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2014;9(11):e111775.

Varela RE, Vernberg EM, Sanchez-Sosa JJ, Riveros A, Mitchell M, Mashunkashey J. Parenting style of Mexican, Mexican American, and Caucasian-non-Hispanic families: social context and cultural influences. J Fam Psychol. 2004;18(4):651–7.

Brug J, van Stralen MM, Chinapaw MJ, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Lien N, Bere E, Singh AS, Maes L, Moreno L, Jan N, et al. Differences in weight status and energy-balance related behaviours according to ethnic background among adolescents in seven countries in Europe: the ENERGY-project. Pediatric obesity. 2012;7(5):399–411.

Chuang RJ, Sharma S, Skala K, Evans A. Ethnic differences in the home environment and physical activity behaviors among low-income, minority preschoolers in Texas. Am J Health Promot. 2013;27(4):270–8.

Skala K, Chuang RJ, Evans A, Hedberg AM, Dave J, Sharma S. Ethnic differences in the home food environment and parental food practices among families of low-income Hispanic and African-American preschoolers. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(6):1014–22.

Schrempft S, van Jaarsveld CH, Fisher A, Wardle J. The obesogenic quality of the home environment: associations with diet, physical activity, TV viewing, and BMI in preschool children. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2015;10(8):e0134490.

Shrewsbury V, Wardle J. Socioeconomic status and adiposity in childhood: a systematic review of cross-sectional studies 1990-2005. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008. 2008;16(2):275–84.

van Ansem WJ, van Lenthe FJ, Schrijvers CT, Rodenburg G, van de Mheen D. Socio-economic inequalities in children’s snack consumption and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption: the contribution of home environmental factors. Br J Nutr. 2014;112(3):467–76.

Wyse R, Campbell E, Nathan N, Wolfenden L. Associations between characteristics of the home food environment and fruit and vegetable intake in preschool children: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:938.

Conlon BA, McGinn AP, Lounsbury DW, Diamantis PM, Groisman-Perelstein AE, Wylie-Rosett J, Isasi CR. The role of parenting practices in the home environment among underserved youth. Child Obes. 2015;11(4):394–405.

Gubbels JS, Van Kann DH, de Vries NK, Thijs C, Kremers SP. The next step in health behavior research: the need for ecological moderation analyses - an application to diet and physical activity at childcare. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:52.

van de Gaar VM, Jansen W, van Grieken A, Borsboom G, Kremers S, Raat H. Effects of an intervention aimed at reducing the intake of sugar-sweetened beverages in primary school children: a controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:98.

Swertz O, Duimelaar P, Thijssen J. Statistics Netherlands. Migrants in the Netherlands 2004. Voorburg/Heerlen, the Netherlands: Statistics Netherlands; 2004.

Netherlands S. Dutch standard classification of education 2003. Statistics Netherlands: Voorburg/Heerlen, Netherlands; 2004.

Bulk-Bunschoten AMW, Renders CM, Leerdam FJM, Hirasing RA. Protocol for detection of overweight in preventive youth health care. [Signaleringsprotocol overgewicht in de jeugdgezondheidszorg]. In. Amsterdam: VUMC; 2004.

Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320(7244):1240–3.

van der Horst K, Oenema A, van de Looij-Jansen P, Brug J. The ENDORSE study: research into environmental determinants of obesity related behaviors in Rotterdam schoolchildren. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:142.

Veldhuis L, Struijk MK, Kroeze W, Oenema A, Renders CM, Bulk-Bunschoten AM, Hirasing RA, Raat H. ‘Be active, eat right’, evaluation of an overweight prevention protocol among 5-year-old children: design of a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:177.

Oluka OC, Nie S, Sun Y. Quality assessment of TPB-based questionnaires: a systematic review. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2014;9(4):e94419.

Francis J, Eccles MP, Johnston M, Walker AE, Grimshaw JM, Foy R, Kaner EFS, Smith L, Bonetti D. Constructing questionnaires based on the theory of planned behaviour: A manual for health services researchers. In. Newcastle, United Kingdom: Centre for Health Services Research, University of Newcastle; 2004.

Gardner B, Abraham C, Lally P, de Bruijn GJ. Towards parsimony in habit measurement: testing the convergent and predictive validity of an automaticity subscale of the Self-Report Habit Index. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:102.

Verplanken B, Orbell S. Reflections on Past Behavior: A Self-Report Index of Habit Strength. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2003;33(6):8.

de Vet HC, Terwee CB, Knol DL, Bouter LM. When to use agreement versus reliability measures. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(10):1033–9.

Field A. Discovering statistics using SPSS. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications; 2005.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–7.

Bauer KW, Neumark-Sztainer D, Fulkerson JA, Hannan PJ, Story M. Familial correlates of adolescent girls’ physical activity, television use, dietary intake, weight, and body composition. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:25.

van Grieken A, Renders CM, van de Gaar VM, Hirasing RA, Raat H. Associations between the home environment and children's sweet beverage consumption at 2-year follow-up: the 'Be active, eat right' study. Pediatr Obes. 2014;10(2):126–33.

Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Fernandez ME. Planning health promotion programs, an intervention mapping approach. 3rd ed. Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass; 2011.

Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31 Suppl 1:S19–26.

Geboers B, de Winter AF, Luten KA, Jansen CJ, Reijneveld SA. The association of health literacy with physical activity and nutritional behavior in older adults, and its social cognitive mediators. J Health Commun. 2014;19 Suppl 2:61–76.

Speirs KE, Messina LA, Munger AL, Grutzmacher SK. Health literacy and nutrition behaviors among low-income adults. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(3):1082–91.

von Wagner C, Knight K, Steptoe A, Wardle J. Functional health literacy and health-promoting behaviour in a national sample of British adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(12):1086–90.

Sanders LM, Federico S, Klass P, Abrams MA, Dreyer B. Literacy and child health: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(2):131–40.

Morrison AK, Schapira MM, Gorelick MH, Hoffmann RG, Brousseau DC. Low caregiver health literacy is associated with higher pediatric emergency department use and nonurgent visits. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(3):309–14.

Morrison AK, Myrvik MP, Brousseau DC, Hoffmann RG, Stanley RM. The relationship between parent health literacy and pediatric emergency department utilization: a systematic review. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(5):421–9.

Burrows TL, Martin RJ, Collins CE. A systematic review of the validity of dietary assessment methods in children when compared with the method of doubly labeled water. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(10):1501–10.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of the Dutch project CIAO, which stands for Consortium Integrated Approach Overweight. Within CIAO, several studies are conducted investigating the different components of the EPODE approach (EPODE is an abbreviation for: Ensemble Prévenons l’Obésité Des Enfants, meaning Together Let's Prevent Childhood Obesity).

Funding

This study is funded by a grant from ZonMw, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, project no. 200100001 (Grant application no. 50-50102-96-015). The publication of this study was supported by a grant of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). The funding bodies did not have any role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the Erasmus University Medical Centre. Researchers may contact the corresponding author on how to access the data.

Authors’ contributions

VMvdG and AvG conceived the idea. VMvdG was primarily responsible for drafting the manuscript and Tables. VMvdG is responsible for the data collection, data analysis and reporting the study results. AvG contributed to the draft of the manuscript and supervised the study. AvG, WJ and HR helped to refine the manuscript. All authors regularly participated in discussing the design and protocols used in the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Medical and Ethical Review Committee of the Erasmus Medical Centre issued a ‘declaration of no objection’ (i.e. formal waver) for this study (reference number MEC-2011-183).

Passive parental consent was obtained. Parents (and children) received a brochure with information to notify and inform them about the intervention and study participation. The study was also announced by the school, via the school letter and through the teachers and by flyers which were visible throughout the school. Parents (and children) were free to refuse participation without giving any explanation. They could do so by informing one of the teachers at their school or one of the researchers when present at school. At all times, the researchers could be contacted by a special phone-number or e-mail, for instance to decline participation [54].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Descriptive results and scale information for the family and home-related factors (n = 644). (PDF 142 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S2.

P-values for interaction between ethnic background and the determinants on child’s SSB intake in litre per day (n = 644). (PDF 219 kb)

Additional file 3: Tables S3-S6.

Table S3. SSB intake in servings per day for the overall sample and according to ethnic background of the child (n = 644). Table S4. P-values for interaction between ethnic background and the determinants on child’s SSB intake in servings per day (n = 644). Table S5. Results from the logistic regression models evaluating the associations between family and home-related factors and child’s SSB intake in servings per day (≤2 vs >2). Table S6. Results from the full logistic regression model evaluating the associations between family and home-related factors and child’s SSB intake in servings per day (≤2 vs >2) according to ethnic background child. (PDF 281 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

van de Gaar, V.M., van Grieken, A., Jansen, W. et al. Children’s sugar-sweetened beverages consumption: associations with family and home-related factors, differences within ethnic groups explored. BMC Public Health 17, 195 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4095-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4095-0