Abstract

Background

Over the past decade, new diagnoses of HIV have increased eightfold among men who have sex with men (MSM) of other or of mixed ethnicity in the UK. Yet there is little intervention research on HIV among black and minority ethnic (BME) MSM. This article aimed to identify effective HIV and sexual health prevention strategies for BME MSM.

Methods

We searched three databases PubMed, Scopus and PsychInfo using a combination of search terms: MSM or men who have sex with men and women (MSMW); Black and Minority Ethnic; HIV or sexual health; and evaluation, intervention, program* or implementation. We identified a total of 19 studies to include in the review including those which used randomised control, pre/post-test and cross-sectional design; in addition, we included intervention development studies.

Results

A total of 12 studies reported statistically significant results in at least one of the behavioural outcomes assessed; one study reported significant increases in HIV knowledge and changes in safer sex practices. In 10 studies, reductions were reported in unprotected anal intercourse (UAI), number of sexual partners, or in both of these measures. Six out of the 13 studies reported reductions in UAI; while seven reported reductions in number of sexual partners. Seven were intervention development studies.

Conclusions

Research into the mechanisms and underpinnings of future sexual health interventions is urgently needed in order to reduce HIV and other sexually transmitted infection (STI) among UK BME MSM. The design of interventions should be informed by the members of these groups for whom they are targeted to ensure the cultural and linguistic sensitivity of the tools and approaches generated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Men who have sex with men (MSM) continue to be the group most affected by HIV infection [1]. Estimates suggest that 62,880 MSM are living with HIV in the UK, and that an estimated 7,200 MSM living with HIV are unaware of their serostatus. In the general population, approximately 4 men in 1,000 are living with HIV; by contrast, among MSM aged 15–59, 59 men per 1,000 are living with HIV. MSM constituted 55 % of all new HIV diagnoses in 2014 [1]. HIV prevalence is highest in areas of deprivation in England and Wales (E&W), particularly in London. The capital is also the most ethnically diverse area across all of the regions in E&W with above average proportions for most Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) groups [2]. Yet despite recent prioritisation in public health strategies for E&W [3], there is relatively little research from these countries (or the other countries of the United Kingdom) which could underpin effective interventions to reduce sexual risk-taking among BME MSM and promote healthy sexual behaviours. This review is timely given the recognition of the increasing burden of HIV among BME MSM in E&W. It seeks to inform the recent implementation of a strategic framework to reduce sexual health inequalities and ensure that MSM from BME communities enjoy long, healthy lives and maintain fulfilling social and sexual relationships [4]. Because of the organisation of public health agencies in the United Kingdom, the following four sections highlight issues pertaining to the context of E&W.

HIV diagnoses and transmission among black and minority ethnic MSM

Public Health England collect annual surveillance relating to diagnosis and routes of transmission; these figures indicate that men of white ethnicity comprise 84 % (38,429 of 45,679) of cases of newly diagnosed MSM with HIV in E&W with a route of exposure through sex with men [5]. By comparison, 14.6 % of the total number of men diagnosed (6,654 of 45,679) are among BME men who are exposed in this way. There has also a more than 82 % increase of new HIV diagnoses among ‘Other’ and ‘mixed heritage’ MSM (242 to 442). Increasing proportions of BME MSM who have been diagnosed with HIV have been seen for care: among Black-Caribbean men there is more than 100 % increase (408 in 2005 to 837 in 2014) while among Black African men the increase has been 126 % (267 to 605).

Defining black and minority ethnic men

Britain has a long-standing history and heritage of different cultures and communities which reflect both its geography and its history. The majority of previous studies around MSM from ethnically diverse groups have been conducted in the USA. While there may be several shared concerns, there are also number of differences between BME communities in E&W and the USA, not only in the terminology used, but also their countries of origin. Minority ethnic groups in the USA constitute 30 % of the population comprising Hispanic (16 %); Black African or American (14 %) with smaller proportions from Asian, mixed, Native American and Pacific Islander groups [6, 7]. In E&W, people from ethnic minority groups constitute 14% of the population [8] with people from the diaspora of India and Pakistan forming the largest minorities.

The psychological impact of a HIV diagnosis on MSM

The introduction of anti-retroviral therapies (ART) in the mid-1990s has meant that HIV has come to be construed and experienced as a chronic, life-altering, rather than life-limiting illness. Although the majority of HIV-positive individuals with access to ART now have a near normal life expectancy, there is evidence that MSM experience a sense of identity crisis which can be particularly acute in the period immediately following diagnosis [9]. There are a number of psychological sequelae for MSM living with HIV including extreme distress, depression and managing the social stigma associated with the virus. The impact on men’s psychological health may inhibit compliance with public health messages; affect their health-seeking and coping behaviours; their self-efficacy in reducing risk; adherence to medication; quality of life and social well-being [10]. Because no vaccine has been developed for HIV, reducing risk behaviours still constitutes the best strategy for reducing transmission.

Research into BME communities further demonstrates the psychological challenges of HIV infection. Initial responses to a positive diagnosis among members of Caribbean heterosexual communities in London included struggling with multifaceted loss: of their known self, their present life, their envisioned future and the expected role of their partner [11]. Among Black young gay and bisexual men in New York, perceptions of social acceptance were negatively correlated with sexual risk taking [12]. Recognising the impact of a positive diagnosis on psychological health requires that models and interventions for changes in health behaviour take account of distress and the possibility of depression [13]. Public health approaches that aim to increase public willingness to test for HIV, thereby reducing the prevalence of undiagnosed HIV, should be attentive to the psychosocial factors that underpin both testing and a positive diagnosis.

HIV risks and inequalities

Despite the increasing incidence of HIV among BME MSM, there is relatively little UK research about their distinct risks and health behaviours. Evidence from a three country comparative study of disparities in HIV risks and infection found that only seven per cent of studies were conducted in the UK [14]. There are contradictory findings in existing work on sexual risk-taking among BME MSM. A London clinic study found that BME MSM were significantly more likely to report unprotected anal intercourse with casual male partners in comparison with white MSM [15]. Furthermore, epidemiological research in E&W found evidence that BME MSM are more likely to report high risk sexual behaviour than other MSM, with Black Caribbean and Black African communities in particular experiencing poor sexual health and high rates of bacterial STIs [16]. This study revealed that BME MSM lack culturally appropriate information, safe spaces and social networks to meet their sexual health needs.

By contrast, a meta-analysis revealed that BME MSM were less likely than white MSM to identify as gay men or to disclose their sexuality to others. The study found that BME MSM engaged in fewer risk behaviours, reported less unprotected anal intercourse, had fewer male partners and more condom use during anal sex than other MSM [14]. Yet regardless of the greater likelihood of adopting safer sex behaviours reported in this paper, BME MSM were three times more likely to test HIV positive and six times more likely to have an undiagnosed HIV infection than other MSM [14]. These findings may indicate health inequalities between BME MSM and their white MSM counterparts because early diagnosis and entry into care improve clinical outcomes. The meta-analysis also revealed important differences in HIV risk between MSM in the UK and the USA and underlines the caution required in transferring international research and epidemiological data to a British context:

-

BME MSM in the UK are more likely than white MSM to test HIV positive or to ever have an STI or a viral STI;

-

BME men in the UK, unlike in Canada and the USA, were more likely to have a history of substance misuse;

-

UK BME MSM were more likely to get tested for HIV, but less likely to have heard of post-exposure (PEP) and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) than were white MSM;

-

Among HIV-positive MSM, UK black MSM were less likely to access combination anti-retroviral therapy (ART) than were white MSM;

-

In the USA, black MSM engaged in fewer HIV risk behaviours than did other MSM;

-

UK BME MSM were equally likely as white MSM to adopt safer sex behaviours;

-

BME MSM across the studies were more likely to be affected by structural factors such as unemployment, low levels of educational achievement and having been in prison [14].

Of relevance to this study is the invaluable role provided by community based organisations in supporting people living with HIV. In a study of access to HIV community based services in Northern England, Madden et al. found that attendance was highest in the most deprived areas [17]. Community organisations were shown to provide effective support for the most vulnerable members of society: compared with white UK nationals, attendance was significantly higher among non-UK nationals of uncertain residency status, refugees, migrant workers, temporary visitors and BME groups. The authors suggest the role of community based organisations is vital to the effective management of HIV. Poverty, alongside individual, social and structural factors including migration and HIV stigma and discrimination contribute to sexual health inequalities.

As indicated previously, rates of HIV infection are not evenly distributed across the population; health behaviour theory suggests that the interplay of multiple inequalities compounds HIV risk. Syndemic theory [18] provides an explanatory framework for these co-occurring factors which may include childhood sexual abuse, depression, polydrug misuse [19]; in addition, wider social factors such as migration, poverty and racism may have an ‘additive relationship’ to HIV risk [18]. The current paper builds on a previous review by Maulsby et al. which systematically evaluated the US literature (published prior to 2012) related to HIV behavioural change interventions [20]. This review contextualises MSM behavioural change interventions with reference to HIV and sexual health knowledge and psychological well-being. Since it is intended that this review will inform future interventions in an English and Welsh context, the international literature on efficacy studies was included. In addition, this review includes a more diverse group of BME men and expands the focus to include sexual health interventions in addition to HIV. It also complements a meta-analysis in which Millet et al. [14] found evidence of HIV risks and health inequalities among black MSM in the UK. The review seeks to extrapolate evidence relevant to the E&W context. By answering the question “What constitutes effective intervention research for BME MSM?” we seek to inform the development of implementation research and intervention programmes for these communities in E&W; in addition we aim to underpin public health strategies for this overlooked group of MSM.

Purpose

-

to provide a comprehensive review of the literature on sexual health interventions, in addition to HIV/AIDS;

-

to complement an existing review of black (i.e. African-American) MSM by including MSM from additional minority ethnic groups;

-

to identify all articles published between 1983–2015. Public health responses for gay male communities were introduced in 1983–4 in E&W [21];

-

to identify effective sexual health prevention intervention strategies for BME MSM.

Aims

-

to elucidate shortcomings and gaps associated with existing sexual health interventions. What aspects promote or inhibit attitudinal/behavioural change? What aspects contribute positively to psychological wellbeing?

-

to identify effective sexual health prevention strategies for BME MSM;

-

to carve out pathways for future research in this area and to provide some preliminary recommendations concerning the development of evidence-based interventions.

Methods

Eligibility criteria and study selection

The authors agreed a protocol, which was informed by the updated PRISMA-P checklist for the reporting of systematic reviews [22] following extensive discussion regarding appropriate search terms and relevant databases. We searched three databases PubMed, Scopus and PsycINFO on 16 November 2015 using a combination of search terms: MSM, men who have sex with men and women (MSMW), gay, bisexual, homosexual; BME, black, African, Caribbean, Latin*, Asian; HIV, AIDS, sexual, evaluation, intervention, training, program*, implementation.

We included research articles published in the peer-reviewed literature, as well as on-going and in press studies. Theses, case studies and editorials were excluded. The interventions included were specifically designed for BME/ black/African Americans, Hispanic/Latinos, and Asian and Pacific Islanders MSM/MSMW. Studies solely with MSM participants were selected for inclusion where BME MSM constituted the majority (>85 %) of the sample. Outcomes related to reducing risk behaviours were included such as number of sexual partners, sex with/without condoms; skills, for example, condom use negotiation, as well as psycho-social outcomes such as HIV/AIDS and other STI knowledge, psychological constructs such as self-esteem and social connectedness. Studies conducted in English in countries with black and minority ethnic populations were included. Studies identified by Maulsby et al. were excluded to avoid duplication of findings [20].

Quality assessment and data extraction

The appraisal of studies was organised in four distinct stages: (1) records identification; (2) records title screening; (3) records abstract screening; (4) full text assessment and final decision for inclusion. Fifty-eight papers were screened by abstract in stage 3 and 28 were retained. We used a modified version of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool to evaluate papers for methodological rigour and data relevance (Retrieved 20.11.15 from http://www.casp-uk.net). Consisting of 9 criteria, each item was ranked on a three-point scale (0 = weak; 1 = moderate; 2 = strong) and were appraised for eligibility and inclusion (see supplementary data). Quality assessment was undertaken by two reviewers and decisions made through discussion, involving a third reviewer as necessary. On consensus, each study was scored a quality rating: studies scoring 13–18 were scored as ‘high’ quality; 7–12 were ranked as ‘moderate’ quality; and 1–6 scored a ‘low’ quality rating. The quality appraisal ratings for each included study are presented in the supplementary data file. In stage 4, data from each retained paper were entered into extraction tables giving details about participants, interventions, comparators and outcomes (PICO) [23]. Behavioural outcomes include: number of sexual partners, sex with condoms, oral sex; and the review also identified psychosocial outcomes: for example, negotiation of safer sex and self-esteem by which men develop skills to protect their own health. A PRISMA flow chart identified the results at each of the four stages (see supplementary data) in accordance with PRISMA methodological guidance [22]. We conducted an integrative review of the data from the 13 efficacy studies which allows for the inclusion of experimental and non-experimental research which is the most appropriate due to the heterogeneity of the studies [24].

Data analysis and synthesis

The results were analysed and synthesised drawing on an approach similar to that proposed by Whittemore and Knafl [24] of data reduction, data display, data comparison and verification of conclusions. The data were reduced by extracting key findings which were then displayed (Table 1). This enabled an iterative process of identifying patterns and themes. Results were then grouped together into two overarching categories of behavioural and psychosocial outcomes. At the presentation stage, explicit details from the primary sources were included to support the conclusions drawn.

Results

Our research identified 173 records after duplicates were removed. Of these, 115 were excluded after two members of the team screened them independently. Fifty eight were retained for screening by abstract. A total of 28 studies were deemed to be potentially relevant for this review and included for full-text assessment. Of these, nine were excluded: six were not intervention studies, two did not focus on BME MSM and one was conducted in a country with a Latino majority population. A total of 19 studies were included in this review of which 13 had findings published in peer-reviewed journals, six were peer-reviewed studies at an intervention development stage, and a recently completed ‘grey’ study in E&W [25]. We were unable to identify any published studies of HIV or sexual health interventions among BME MSM in E&W. Table 1 gives a brief description of the citation, country of origin, aim of the study, theoretical orientation, participant characteristics, methods and comparators, primary and secondary outcomes; limitations and conclusions.

Study participants were of African-American, Latino (Spanish speaking) and Asian Pacific Islander heritage. Most studies were US based and participants were drawn from the predominantly urban communities of New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Toronto, Chicago and Baltimore. Some studies were targeted to particular sub-populations of MSM communities including the African-American House Ball community, Mexican farmworkers, young MSM of colour, behaviourally bisexual men, injection drug-using MSM and BME men who had experienced sexual abuse. Participants were men with HIV negative, positive and unknown status. Typically, men were recruited through convenience sampling, assessed for eligibility by screening interview and randomly assigned to an intervention or a control group. Study sample sizes ranged from 40–503 participants.

Studies adopted diverse theoretical perspectives and domains of interest which ranged from psycho-social concerns, HIV testing to the assessment of cortisol levels in urine samples. Themes included men’s social context: social isolation, migration, stigma and oppression, developing a positive identity, body image, social support; HIV prevention, risk reduction and condom use; lifestyle concerns: diet, smoking and exercise; satisfying sexual behaviour.

Six studies were conducted among Latino/ Spanish speaking populations, seven studies were undertaken among Black/ African-American communities, one of Asian Pacific Islander and two studies included both Latino and Black/African American men. Strategies adopted to ensure the cultural sensitivity of interventions included developing collaborative partnerships with a range of Community-Based Organisations such as health centres catering for gay and bisexual men’s communities alongside organisations for particular ethnic or cultural groups (e.g. the Centre for Spanish Speaking Peoples). In some studies, Spanish constituted the working language of the research team and the advisory committee meetings and interventions were all conducted in Spanish. Methods included the use of culturally appropriate materials such as a commissioned video, sexual diaries, word association, problem solving, analysis of Spanish proverbs, surveys, interviews and focus groups. Five studies were informed by the work of Diaz, some of them adapted or used the programme he developed in the handbook Hermanos de Luna Y Sol.

Intervention design

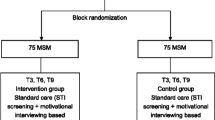

Seven out of the 13 efficacy studies [26–32] used a randomised controlled trial (RCT) design in which participants were randomly assigned to the experimental or the control condition. Of these seven studies, two [26, 27] had an experimental condition and a waiting list as the control condition. In two studies [30, 31] the control condition comprised of general health promotion focusing on diet and exercise; for two studies [28, 32] the control condition consisted of a HIV risk reduction session (e.g. based on a standard HIV test counselling approach of 15–25 min); and in one, the control group were offered a HIV test [29]. The length and number of sessions varied across the studies: from a single 45–60 min long intervention [29] to an intervention with twice weekly 2-h sessions over a three week period [24]. Two studies in this review used a pre-post design [33, 34]; two studies used a repeated cross-sectional design [35, 36]; one used a mixed design of RCT with a repeated cross-sectional design [37], and one used a repeated measures design with no control group [38].

The studies revealed innovative and diverse approaches to HIV prevention intervention. Seven studies used group-based approaches; one study used individual sessions while another used a combination of group–based and individual sessions. Three studies adopted the Popular Opinion Leader intervention, modelled on the work of Kelly [39], which provides training for peer leaders to enable them to use social networks to deliver HIV prevention messages. This approach was used in particular to deliver risk reduction messages to ‘clandestine’ or marginalised groups such as Mexican farmworkers and the House Ball community.

Measures for assessment

In eight out of the 13 efficacy studies, the primary outcomes assessed were: unprotected anal intercourse (UAI), unprotected anal and vaginal intercourse (UAVI) and condom protected intercourse (CPI). Six of the 13 studies used the risk behaviour outcome measure of reductions in the number of sexual partners between pre and post intervention. Secondary outcome measures included reductions in sex under the influence of substances (2), increased HIV testing (2), HIV/AIDS knowledge and HIV risk-behaviour knowledge (1) and psychological and social constructs of human behaviour (3). One study (Williams) assessed UAVI alongside bio-physical markers to ascertain stress levels.

Reductions in behavioural risks

A total of 12 studies reported statistically significant results in at least one of the behavioural outcomes assessed [26–35, 37, 38], while Somerville [36] reported significant changes in safer sex practices. Across ten out of the 13 efficacy studies, reductions were reported in unprotected anal intercourse (UAI), number of sexual partners, or in both of these measures [28, 30, 37]. Six out of the 13 studies reported reductions in UAI [27, 30, 32–34, 37]. Seven studies reported reductions in number of sexual partners [28–30, 32, 35, 38, 39]. These sexual behaviours are considered to increase the risk of HIV/ other STI transmission. In three studies, the reductions in UAI and in the number of sexual partners occurred in both the efficacy arm of the intervention and in the control group [27, 31, 32].

The sole individual intervention [30] included in this review found significant overall declines in UAI, but there were no significant differences between the experimental and the control conditions. Two studies adapted the Popular Opinion Leader model: Promoting Ovahness through Safer Sex Education (POSSE) [35] and the Young Latino Promotores project which also aimed to build capacity in community based organisations to tackle HIV prevention [36]. Statistically significant declines were observed for multiple sexual partners, UAI with any male partners, and with male partners of unknown HIV status [36]. Increase in safer sex using condoms was observed, but this was not statistically significant [36].

Four RCT studies [27–30] showed behavioural change in the intervention group in comparison with the control condition. Two RCTs showed significant results across the overall sample [26, 31]. Two studies which showed low to moderate effectiveness used the Popular Opinion Leader model with a pre-post design [35, 36]. A pre-post study by Vega reported significant reductions in number of sexual partners and in high risk sexual behaviours (i.e. UAI) [34].

Psychosocial outcomes

Increases in knowledge about HIV/AIDS were observed in three studies [31, 34, 36]. Vega [34] showed increases in psychosocial constructs of self-esteem, coping, social provisions and collective self-esteem (that is, public Latino identities). One study found significant increases in knowledge together with increased social norms about the acceptance of safer sex [36]. A study of men who had been sexually abused in childhood found reductions in depression [31].

We have also identified six intervention development studies (Table 2) [40–45], of which I am men’s health [40] is the only study where PrEP adherence formed the outcome measure. In this study, an overall compliance rate of 73 % among young black MSM was found. This is important as PrEP is an emerging HIV prevention tool that has gained ground among groups at high risk of HIV acquisition, such as MSM in San Francisco (although at the time of writing PrEP is not licensed for use in the UK). A formative study using focus groups [41] sought to inform the development of a mobile phone-based HIV intervention; findings suggested the need for a smartphone application or website with a text messaging component. A second feasibility study using focus groups (N = 105) explored the use of web-based HIV prevention for drug injecting Black MSMW [42]. Findings suggest the need for dedicated space with HIV prevention programmes for this group of men which should include holistic services including job assistance. Solorio developed HIV prevention messages for young Latino MSM who do not identify as gay and translated and tested these messages as Public Service Announcements [43]. HealthMpowerment.org is a mobile phone-optimised online intervention with young BME MSM and transgender women which reported statistically significant improvements in social support, social isolation and depressive symptoms [44]. HOLA en Grupos is a Centre for Disease Control supported evaluation of behavioural interventions for potential use with Latino communities [45].

Discussion

The overall results of this review indicate moderate to high efficacy of behavioural change interventions in African-American, Latino and Asian and Pacific Islander (API) men exclusively in the North American context. Six studies showed reductions in condomless anal intercourse, while seven studies showed a decline in the number of sexual partners: in the absence of other prevention methods, these behaviours place men at increased risk of HIV acquisition.

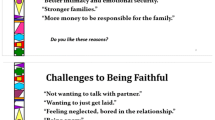

A number of the studies reported extensive preparatory work to ensure the relevance of interventions, including the development of culturally sensitive approaches and materials. Many studies adopted a holistic approach exploring the context for men’s sexual behaviours within the realities of their everyday lives, which is also highlighted in psychotherapeutic approaches to HIV prevention [46]. Moreover, consistent with previous research into the potential psychosocial antecedents of sexual risk-taking, interventions [47, 48] addressed social issues including housing and migration, psycho-social constructs such as isolation, self-esteem and negotiating skills, inter-personal concerns, for example, building social networks in addition to men’s access to health and social services. Fewer studies in the review showed evidence of psycho-social change following the intervention, with the exception of SOMOS which reported increases in psychosocial constructs e.g. self-esteem and coping while Es-Him found a reduction in depression [31]. Social isolation continues to be a predictor of sexual risk-taking and is associated with other factors which increase risk such as depression and substance misuse [33].

More specifically, these psychosocial factors may reduce the individual’s engagement with ability to negotiate safer sex practices, such as negotiating condom use, discussing HIV with partners, or adhering to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Previous research has indicated that behavioural change interventions alone will not lead to reductions in HIV or sexually transmitted infections among BME MSM because recent increases in diagnoses do not seem to be attributable to an increased prevalence of at risk behaviours in comparison to other MSM [14]. Rather, it is necessary to increase knowledge regarding transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections and willingness to undergo appropriate testing [49, 50]. Knowledge of HIV prevention methods, other than the use of condoms, such as PEP and PrEP is low among BME MSM, which can contribute to increasing HIV incidence [51]. Moreover, they are less likely to access care and continue using care and treatment regimens in comparison with other MSM. This can further exacerbate health inequalities among BME MSM [52]. In a UK study of 16,406 BME MSM, the proportion with no follow up after HIV diagnosis was higher than among white MSM. Permanent loss to follow up was highest in other/mixed groups and lowest in Indian/Pakistani /Bangladeshi groups. The importance of follow up is underscored because once BME MSM are receiving ART, there are no differences in virological, immunological and clinical outcomes [53]. These findings highlight a need to extend culturally sensitive approaches to the wider healthcare environment.

A number of factors contributed to the effectiveness of the interventions in our review in reducing HIV risk behaviours. Notably, studies were underpinned by theoretical frameworks and risk behaviours were addressed in the wider context of men’s lives. Thus, it appears that those interventions that integrate community-based knowledge in broader theoretical frameworks regarding risk-taking behaviour are more likely to be effective. Interventions formed an integrated programme working alongside community based organisations, some were concurrently conducted in multiple cities, studies were conducted over a 3 – 6 month timescale following the intervention, retention rates were high and studies used a range of incentives to minimise attrition. This suggests that future interventions can be conducted and evaluated over longer time periods during which actual behaviour change is most likely to be observable.

Intervention development studies (IDS)

A number of pilot studies and intervention development research projects were also recognised. There is a promising trend towards designing behavioural and psychosocial change approaches through a complex, iterative and multiple staged process involving individuals who are members of the communities for which the interventions are designed. This can help facilitate a culturally and linguistically appropriate perspective that takes into consideration the factors that are likely to promote positive engagement with the intervention. This cultural perspective is then integrated into theoretical models of behaviour change. Some of the IDS were focused on raising health awareness, providing HIV/STIs prevention or offering sexual health training through electronic means of communication. These IDS were pilot interventions planned and disseminated through contemporary methods of communication (e.g. social media and mobile communication). This is consistent with the prominence of internet, mobile and application communication within young MSM communities with regard to gay in-group socialising, and sexual partner seeking [54]. Finally, we identified one study [40] that discussed adherence to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in young MSM of colour. This is important in view of the promising findings from recent clinical trials that PrEP constitutes an effective barrier against HIV infection among MSM [55]. Moving beyond the use of condoms as the sole HIV prevention strategy, this emerging work on PrEP could further complement and enhance existing predominantly condom-based HIV prevention interventions among BME MSM communities.

Limitations

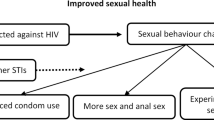

While this systematic review identifies a number of important factors that underpin effective sexual health interventions, there are some limitations. Specifically, the review focussed on papers published in peer reviewed journals and excluded grey literature. Although the grey literature may not be methodologically robust, it might indicate specific insights which may lead to new research directions. This focus may have biased the results of this review towards studies with significant findings and may have excluded studies with null findings. Moreover, the existing evidence base suffers from some methodological limitations, such as the existence of conflicting and limited evidence which can preclude the formation of robust interventions. For instance, there are inconsistent findings about the link between PrEP use and condom use. While PrEP is protective against HIV, its use without condoms could place MSM at risk of other STIs. The heterogeneity of populations included in studies may also be problematic given the distinct cultural and linguistic needs of particular BME MSM communities. Many of the interventions include only limited follow-up periods which can make it difficult to assess the robustness and duration of the intended behavioural changes. The changing nature of HIV risk-related behaviours and the diverse prevention methods employed by MSM, such as serosorting, strategic positioning and biomedical prevention methods, are not currently reflected and represented in the current interventions and as yet, evaluation of these strategies are poorly represented in the extant literature. Other limitations include the heterogeneity of intervention content and of the outcome measures. Despite these limitations, the review makes an important contribution to developing the knowledge base to inform future behavioural and psychological interventions for BME MSM. The review provides strong evidence that effective interventions for this previously overlooked group of men are underpinned by relevant theoretical frameworks, cultural sensitivity and the involvement of potential users in both the design and delivery of health education and behavioural change approaches. The limitations acknowledged here should be taken into consideration in the development of future interventions.

Conclusions

Despite the relevance of HIV and sexual health risk prevention for BME MSM, this review has not produced any intervention studies conducted within a UK context. Research into the mechanisms and underpinnings of future sexual health interventions is urgently needed in order to reduce HIV and other STI infection among UK BME MSM, who remain a high risk group [3]. There has understandably been a focus on condom-based approaches to HIV prevention but as the contemporary prevention landscape develops, additional approaches will need to be considered. These include biomedical prevention options, such as PEP and PrEP, and seroadapative behaviours, such as serosorting, strategic positioning in sexual encounters, and modification of sexual behavioural practices. In short, while condom use constitutes a highly effective HIV prevention option, there are other options that should also be considered when evaluating future interventions. HIV prevention agencies are increasingly recognising the need to promote other safer sex strategies in addition to condom use. In order for future interventions to be successful, there is an imperative need to acknowledge not only the cultural and linguistic specificities of the groups targeted but also the role of stigma and medical mistrust [56]. While materials developed for North American studies with Hispanic Latino communities for example, may not be relevant to the UK BME communities (i.e. Brazilian/Portuguese speaking communities, South Asian communities, African-Caribbean communities), this review has highlighted methods which may be applied in the British context. For example, effective interventions are characterised by an integrated approach which recognises the complex interplay between behaviours, knowledge and psychosocial factors, such as skills in negotiating safer sexual practices. Health and environmental communication models also suggest that approaches that take identity into account are more likely to be effective in promoting public understanding and behaviour change [57]. The inclusion of “insider” perspectives in the design of appropriate interventions, i.e. from members of the group being targeted, is advantageous because it may facilitate a culturally and linguistically sensitive approach, and also reduce feelings of suspicion and outgroup threat that have been observed in some attempts to reduce sexual risk-taking [44]. The response to such interventions will conceivably be more favourable. Finally, the review indicates that interventions should be structured over a timeframe that allows for the collection and analysis of follow-up data, particularly as behaviour change can take a while to manifest itself in evaluation research.

Abbreviations

ART, anti-retroviral therapies; BME, black and minority ethnic; CPI, condom protected intercourse; IDS, intervention development studies; MSM, men who have sex with men; MSMW, men who have sex with men and women; PEP, Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP); PICO, participants, interventions, comparators and outcomes; PREP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; RCT, randomised control trial; STI, sexually transmitted infection; UAI, unprotected anal intercourse; UAVI, unprotected anal and vaginal intercourse

References

Skingsley A, Yin Z, Kirwan P, Croxford S, Chau C, Conti S, Presanis A, Nardone A, Were J, Ogaz D, Furegato M, Hibbert M, Aghaizu A, Murphy G, Tosswill J, Hughes G, Anderson J, Gill ON, Delpech VC and contributors. HIV in the UK – Situation Report 2015: data to end 2014. London: Public Health England, 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/477702/HIV_in_the_UK_2015_report.pdf Accessed 15 Jan 2016

Office for National Statistics (2012) Ethnicity and National identity in England and Wales. http://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/ethnicity/articles/ethnicityandnationalidentityinenglandandwales/2012-12-11 Accessed 15 Jan 2016

PHE (2014) PHE action plan 2015–16 Promoting the health and wellbeing of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/401005/PHEMSMActionPlan.pdf Accessed 30 Mar 2016

Dada, M, Carney, L, Guerra, L. The health and wellbeing of black and minority ethnic gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men: event report. London: Public Health England. 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/383967/HealthWellBeingOfBlackMinorityEthnicMenWhoHaveSexWithMenEventReport2Oct2014.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2016

Public Health England. National HIV surveillance data tables. London: Public Health England. 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/hiv-data-tables. Accessed 14 Jan 2016.

Ennis, SR, Ríos-Vargas, M, Albert, N.G. The Hispanic population 2010. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf. Accessed 5 Feb 2016

Rastogi, S, Johnson, TD, Hoeffel, EM, Drewery, MP. The Black population 2010. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-06.pdf. Accessed 5 Feb 2016

Office for National Statistics. Ethnicity and National Identity in England and Wales 2011. London: Office for National Statistics. 2012. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171776_290558.pdf. Accessed 14 Jan 2016

Flowers P, Davis MM, Larkin M, Church S, Marriott C. Understanding the impact of HIV diagnosis amongst gay men in Scotland: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Psychol Health. 2011;26(10):1378–91.

Wilson PA, Valera P, Martos AJ, Wittlin NM, Muñoz-Laboy MA, Parker RG. Contributions of Qualitative Research in Informing HIV/AIDS Interventions Targeting Black MSM in the United States. J Sex Res 2015, 0(0):1–13

Anderson M, Elam G, Gerver S, Solarin I, Fenton K, Easterbrook P. It took a piece of me: Initial responses to a positive HIV diagnosis by Caribbean people in the UK. AIDS Care Psychol Socio-Med Asp AIDS HIV. 2010;22(12):1493–8.

Walker JJ, Longmire-Avital B, Golub S. Racial and sexual identities as potential buffers to risky sexual behavior for black gay and bisexual emerging adult men. Health Psychol. 2015;34(8):841–6.

Safren SA, Traeger L, Skeer MR, O'Cleirigh C, Meade CS, Covahey C, Mayer KH. Testing a social-cognitive model of HIV transmission risk behaviors in HIV-infected MSM with and without depression. Health Psychol. 2010;29(2):215–21.

Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, Hart TA, Jeffries IV WL, Wilson PA, Rourke SB, Heilig CM, Elford J, Fenton KA, Remis RS. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: A meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):341–8.

Soni S, Bond K, Fox E, Grieve AP, Sethi G. Black and minority ethnic men who have sex with men: A London genitourinary medicine clinic experience. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19(9):617–9.

Dougan S, Elford J, Rice B, Brown AE, Sinka K, Evans BG, Gill ON, Fenton KA. Epidemiology of HIV among black and minority ethnic men who have sex with men in England and Wales. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(4):345–50.

Madden HC, Phillips-Howard PA, Hargreaves SC, Downing J, Bellis MA, Vivancos R, Morley C, Syed Q, Cook PA. Access to HIV community services by vulnerable populations: evidence from an enhanced HIV/AIDS surveillance system. AIDS Care. 2011;23(5):542–9.

Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Herrick A, Donenberg G. Psychosocial health problems increase risk for HIV among urban young men who have sex with men: Preliminary evidence of a syndemic in need of attention. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34(1):37–45.

Parsons JT, Grov C, Golub SA. Sexual compulsivity, co-occurring psychosocial health problems, and HIV risk among gay and bisexual men: Further evidence of a syndemic. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):156–62.

Maulsby C, Millett G, Lindsey K, Kelley R, Johnson K, Montoya D, Holtgrave D. A systematic review of HIV interventions for black men who have sex with men (MSM). BMC Public Health. 2013;13:625. 2458-13-625.

Nicoll A, Hughes G, Donnelly M, Livingstone S, De Angelis D, Fenton K, Evans B, Gill ON, Catchpole M. Assessing the impact of national anti-HIV sexual health campaigns: trends in the transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in England. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77(4):242–7.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (prisma-p) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ (Online). 2015;349:g7647.

Bettany-Saltikov J. Learning how to undertake a systematic review: part 2. Nurs Stand. 2010;24(51):47–56.

Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546–53.

Jaspal, R, Fish, J Williamson, I, Papaloukas, P. Public Health England black and minority ethnic men who have sex with men project evaluation report. London: Public Health England. 2016. www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/525843/BlackandminorityethnicmenwhohavesexwithmenProjectevaluationandsystematicreview.pdf. Accessed 2 June 2016.

Carballo-Diéguez A, Dolezal C, Leu C, Nieves L, Díaz F, Decena C, Balan I. A randomized controlled trial to test an HIV-prevention intervention for Latino gay and bisexual men: Lessons learned. AIDS Care. 2005;17(3):314–28.

Choi K, Lew S, Vittinghoff E, Catania JA, Barrett DC, Coates TJ. The efficacy of brief group counseling in HIV risk reduction among homosexual Asian and Pacific Islander men. AIDS. 1996;10(1):81–7.

Harawa NT, Williams JK, McCuller WJ, Ramamurthi HC, Lee M, Shapiro MF, Norris KC, Cunningham WE. Efficacy of a culturally congruent HIV risk-reduction intervention for behaviorally bisexual black men: Results of a randomized trial. AIDS. 2013;27(12):1979–88.

O’Donnell L, Stueve A, Joseph HA, Flores S. Adapting the voices HIV behavioral intervention for Latino men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(4):767–75.

Jemmott Iii JB, Jemmott LS, O’Leary A, Icard LD, Rutledge SE, Stevens R, Hsu J, Stephens AJ. On the efficacy and mediation of a One-on-One HIV risk-reduction intervention for African American Men Who have Sex with Men: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2015;9(7):1247–62.

Williams JK, Glover DA, Wyatt GE, Kisler K, Liu H, Zhang M. A sexual risk and stress reduction intervention designed for HIV-positive bisexual African American men with childhood sexual abuse histories. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(8):1476–84.

Tobin K, Kuramoto SJ, German D, Fields E, Spikes PS, Patterson J, Latkin C. Unity in diversity: results of a randomized clinical culturally tailored pilot HIV prevention intervention trial in Baltimore, Maryland, for African American Men Who have Sex with Men. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(3):286–95.

Adam BD, Betancourt G, Serrano-Sánchez A. Development of an HIV prevention and life skills program for Spanish-speaking gay and bisexual newcomers to Canada. Can J Hum Sex. 2011;20(1–2):11–7.

Vega MY, Spieldenner AR, DeLeon D, Nieto BX, Stroman CA. SOMOS: Evaluation of an HIV prevention intervention for Latino gay men. Health Educ Res. 2011;26(3):407–18.

Hosek SG, Lemos D, Hotton AL, Isabel Fernandez M, Telander K, Footer D, Bell M. An HIV intervention tailored for black young men who have sex with men in the House Ball Community. AIDS Care. 2015;27(3):355–62.

Somerville GG, Diaz S, Davis S, Coleman KD, Taveras S. Adapting the popular opinion leader intervention for Latino young migrant Men Who have Sex with Men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18:137–48.

Young SD, Cumberland WG, Lee SJ, Jaganath D, Szekeres G, Coates T. Social networking technologies as an emerging tool for HIV prevention: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(5):318–24.

Stein R. Reduced sexual risk behaviors among young Men of color Who have Sex with Men: findings from the community-based organization behavioral outcomes of many Men, many voices (CBOP-3MV) project. Prev Sci. 2015;16(8):1147–58.

Kelly JA, St. Lawrence JS, Diaz YE, Stevenson LY, Hauth AC, Brasfield TL, Kalichman SC, Smith JE, Andrew ME. HIV risk behavior reduction following intervention with key opinion leaders of population: An experimental analysis. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(2):168–71.

Daughtridge GW, Conyngham SC, Ramirez N, Koenig HC. I am men’s health: Generating adherence to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (prep) in young men of color who have sex with men. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015;14(2):103–7.

Muessig KE, Pike EC, Fowler B, Legrand S, Parsons JT, Bull SS, Wilson PA, Wohl DA, Hightow-Weidman LB. Putting prevention in their pockets: Developing mobile phone-based HIV interventions for black men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013;27(4):211–22.

Washington TA, Thomas C. Exploring the use of web-based hiv prevention for injection-drug-using black men who have sex with both men and women: A feasibility study. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2010;22(4):432–45.

Solorio R, Norton-Shelpuk P, Forehand M, Martinez M, Aguirre J. HIV prevention messages targeting young Latino immigrant MSM. AIDS Research and Treatment 2014:353092. doi: 10.1155/2014/353092. Epub 2014 Apr 17

Hightow-Weidman LB, Muessig KE, Pike EC, LeGrand S, Baltierra N, Rucker AJ, Wilson P. HealthMpowerment.org: building community through a mobile-optimized, online health promotion intervention. Health Educ Behav. 2015;42(4):493–9.

Rhodes SD, Alonzo J, Mann L, Freeman A, Sun CJ, Garcia M, Painter TM. Enhancement of a locally developed hiv prevention intervention for hispanic/latino MSM: A partnership of community-based organizations, a university, and the centers for disease control and prevention. AIDS Educ Prev. 2015;27(4):312–32.

Shernoff A. Without condoms: unprotected sex, gay men & barebacking. London: Routledge; 2006.

Hickson F, Reid D, Weatherburn P, Stephens M, Nutland W, Boakye P. HIV, sexual risk, and ethnicity among men in England who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(6):443–50.

Parsons JT, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Botsko M, Golub SA. A randomized controlled trial utilizing motivational interviewing to reduce HIV risk and drug use in young gay and bisexual men. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82(1):9–18.

Frye V. “Just because It's Out there, people Aren't going to use It”. HIV self-testing among young, black MSM, and transgender women. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(11):617–24.

Stahlman S, Plant A, Javanbakht M, Cross J, Montoya JA, Bolan R, Kerndt PR. Acceptable interventions to reduce syphilis transmission among high-risk men who have sex with men in Los Angeles. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(3):e88–94.

Mansergh G. Preference for condoms, antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis, or both methods to reduce risk for HIV acquisition among uninfected US black and latino MSM. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70(4):e153–5.

St. Lawrence JS, Kelly JA, Dickson-Gomez J, Owczarzak J, Amirkhanian YA, Sitzler C. Attitudes toward HIV voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) among African American men who have sex with men: Concerns underlying reluctance to test. AIDS Educ Prev. 2015;27(3):195–211.

Sethi G. Uptake and outcome of combination antiretroviral therapy in men who have sex with men according to ethnic group: The UK CHIC study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(5):523–9.

Rice E, Holloway I, Winetrobe H, Rhoades H, Barman-Adhikari A, Gibbs J, Carranza A, Dent D, Dunlap S. Sex risk among young men who have sex with men who use Grindr, a smartphone geosocial networking application. J AIDS Clin Res 2012, 3(SPL ISSUE4).

McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, Dolling DI, Gafos M, Gilson R, Sullivan AK, Clarke A, Reeves I, Schembri G, Mackie N, Bowman C, Lacey CJ, Apea V, Brady M, Fox J, Taylor S, Antonucci S, Khoo SH, Rooney J, Nardone A, Fisher M, McOwan A, Phillips AN, Johnson AM, Gazzard B, Gill ON. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): Effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10013):53–60.

Eaton LA. The Role of Stigma and Medical Mistrust in the Routine Health Care Engagement of Black Men Who Have Sex With Men. American journal of public health (1971) 02, 105(2): e75-e82.

Jaspal R, Nerlich B, Cinnirella M. Human responses to climate change: Social representation, identity and socio-psychological action. Env Commun. 2014;8(1):110–30.

Funding

This review was commissioned by Public Health England (PHE) with funding from the MAC AIDS Foundation as part of a wider project which examined approaches to sexual health and HIV risk behavioural change interventions among Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) Men who have Sex with Men (MSM) in the UK. The findings and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Public Health England.

Availability of supplementary data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the De Montfort University Open Research Archive (DORA) repository in http://hdl.handle.net/2086/12105

Authors’ contribution

JF devised the research protocol, JF and PP conducted the search of the literature, interpreted the findings and wrote the manuscript. RJ and IW revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors participated in subsequent revisions of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Authors’ information

JF and IW are based at the Centre for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Queer Research, De Montfort University, Leicester, LE1 9BH, UK. RJ and PP are based at the Mary Seacole Research Centre, De Montfort University Leicester LE1-9BH, UK.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable for a systematic review.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable for a systematic review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fish, J., Papaloukas, P., Jaspal, R. et al. Equality in sexual health promotion: a systematic review of effective interventions for black and minority ethnic men who have sex with men. BMC Public Health 16, 810 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3418-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3418-x