Abstract

Background

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) pose a serious public health problem globally. The rapid spread of mobile technology creates an opportunity to use innovative methods to reduce the burden of STIs. This systematic review identified recent randomised controlled trials that employed mobile technology to improve sexual health outcomes.

Methods

The following databases were searched for randomised controlled trials of mobile technology based sexual health interventions with any outcome measures and all patient populations: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Global Health, The Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Methodology Register, NHS Health Technology Assessment Database, and Web of Science (science and social science citation index) (Jan 1999–July 2014). Interventions designed to increase adherence to HIV medication were not included. Two authors independently extracted data on the following elements: interventions, allocation concealment, allocation sequence, blinding, completeness of follow-up, and measures of effect. Trials were assessed for methodological quality using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. We calculated effect estimates using intention to treat analysis.

Results

A total of ten randomised trials were identified with nine separate study groups. No trials had a low risk of bias. The trials targeted: 1) promotion of uptake of sexual health services, 2) reduction of risky sexual behaviours and 3) reduction of recall bias in reporting sexual activity. Interventions employed up to five behaviour change techniques. Meta-analysis was not possible due to heterogeneity in trial assessment and reporting. Two trials reported statistically significant improvements in the uptake of sexual health services using SMS reminders compared to controls. One trial increased knowledge. One trial reported promising results in increasing condom use but no trial reported statistically significant increases in condom use. Finally, one trial showed that collection of sexual health information using mobile technology was acceptable.

Conclusions

The findings suggest interventions delivered by SMS interventions can increase uptake of sexual health services and STI testing. High quality trials of interventions using standardised objective measures and employing a wider range of behavioural change techniques are needed to assess if interventions delivered by mobile phone can alter safer sex behaviours carried out between couples and reduce STIs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sexually transmitted infections

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), are a serious worldwide health burden, which if left untreated can lead to a variety of outcomes including cervical cancer, infertility, ectopic pregnancy and mortality [1, 2]. Worldwide it is estimated that half a billion new curable STIs occur each year [3]. Sexual health disease burden varies throughout low, middle and high income countries, with the latest global estimates suggesting an estimated 131 million new cases of chlamydia, 78 million of gonorrhea, 143 million of trichomoniasis and 6 million of syphilis per year [4]. Furthermore, HIV/AIDS ranked six in the top 50 causes of global years of life lost in 2013 [5].

The African region has consistently been reported as having the greatest STI burden with the number of incident cases estimated in 2012 at 37.36 million for trichomoniasis, 12.01 for chlamydia, 11.44 for gonorrhea and 1.84 million for syphilis [4]. In the USA nearly 20 million new STI cases occur every year with direct annual health costs estimated at 16 billion USD [6]. As both developing and developed countries search for new and cost-effective approaches to manage and prevent STIs, there is increasing adoption of electronic and mobile technologies to deliver health promotion, disease prevention interventions and health care services [7, 8].

mHealth

mHealth can be broadly defined as the use of mobile technologies like mobile phones (standard and smart phones), personal digital assistants, handheld and ultra-portable devices (tablets) and others mobile devices in healthcare to improve healthcare systems, support healthcare professionals and provide better health outcomes for patients [9, 10].

The increased use of mHealth worldwide has grown in parallel to the popularity of the domestic uptake and use of mobile technology, in particular mobile phones. By end of 2015 it has been estimated that there would be more than 7 billion active mobile phone subscriptions with 97 % penetration rate worldwide meaning global mobile phone coverage would surpass all other telecommunications technology [11]. The potential benefits of mHealth using mobiles phones and other devices is being explored globally. In 2011 83 % of the 112 participating World Health Organization Member States reported the presence of at least one mHealth initiative in country, with low-income countries (77 %; n = 22) reporting at least one mHealth initiative compared to 87 % (n = 29) of high-income countries [12].

mHealth and STIs systematic reviews

Calls for greater rigor in evaluation has increased the number of mHealth randomised control trials (RCTs) conducted in developed and developing nations. Two previous systematic reviews of controlled trials of m-health interventions from 1999 to 2010 across all health areas (including behaviour change and health service delivery) and regions, identified a total of 117 trials [7, 8]. The reviews found modest benefits for diagnosis and management of health conditions, improvements in smoking cessation and modest increases in attendance with SMS appointment reminders. However, these results should be observed with caution as few of the trials had a low risk of bias. One trial of an adherence to HIV medication intervention showed clinically important reductions in HIV viral load among the intervention group [13]. Three mHealth interventions targeting safer sex behaviours were included in these reviews.

Previous systematic reviews of mHealth interventions for sexual health either targeted a single disease e.g. HIV/AIDS [14, 15] or were specific to Short Message Service (SMS) focusing on only one type of mHealth intervention [16]. The purpose of this systematic review is to update our knowledge of and assess all mHealth interventions for clinic attendance for sexual health and safer sex behaviours (including STI testing, partner notification, condom use number of partners) for all populations, interventions, comparisons, outcomes and studies globally. Interventions designed to increase adherence to HIV medication were not included in the review. This review was conducted by adapting a previously published systematic review protocol [17] for mobile interventions and sexual health and was not registered.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

Participants

All interventions aimed at patients and the general population were included, with the exclusion of interventions targeting health care professionals and researchers.

Interventions

Interventions included all randomised controlled trials utilising mobile technology, including mobile phones, personal digital assistant phones e.g. Blackberry, Palm Pilot, smartphones, enterprise digital assistants, portable media players, e-reader, handheld video-game consoles, handheld and ultra-portable computers such as tablet PCs, smart books and iPads. We excluded desktop personal computers, notebook (laptop) computers, subnotebook computers netbooks, pagers, handheld calculators, pedometers and electronic events-monitoring systems. Additionally, interventions that were mixed mobile technology and non-mobile technology interventions where the treatment and control group both received the mobile technology component, and interventions where there were other treatment differences between the treatment and control groups besides the delivery of the mobile technology components were not included. The focus of this study was on clinic attendance and safer sex behaviours thus studies of adherence to HIV medication were also excluded.

Comparisons

Trials were assessed for methodological quality using the Cochrane risk of bias tool and where possible results were converted to intention-to-treat risk ratios and analysed for statistical significance.

Outcomes

All outcome measures reported in studies meeting the inclusion criteria were extracted. This included both objective and self-reported measures. Primary outcome measures included any objective measure of health, or health service delivery or use. Secondary outcome measures were defined as self-reported health outcomes relating to knowledge and health-seeking behaviours.

Study design

We included all randomised controlled trials. Non-randomised controlled studies were not included.

Literature search

Including the three trials found in previous studies 1999–2010 [7, 8], we used a three-part search strategy to identify studies meeting the inclusion criteria below that have been published between January 2010 and July 2014: (1) we searched electronic bibliographic databases for published work, using a comprehensive search strategy for mHealth sexual health interventions; (2) we searched trial registers for ongoing and recently completed trials; (3) we searched the reference lists of primary studies included in the review and the reference lists of relevant previously published reviews. This ensured all eligible studies 1999–2014 were included in this review.

The following electronic bibliographic databases were searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Global Health, The Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Methodology Register, NHS Health Technology Assessment Database, and Web of Science (science and social science citation index). The search strategy only included terms relating to or describing mHealth interventions for sexual health or health service outcomes meeting the inclusion criteria described below.

All of these terms were combined with the Cochrane Library MEDLINE filter for controlled trials of interventions. The mobile technology search terms were adapted for use with other bibliographic databases in combination with database-specific filters for controlled trials, where these are available. There were no language restrictions. Data from dissertations that meet the inclusion criteria, where these are indexed in the above databases, would also be included. We did not retrieve or include any unpublished data. Ongoing, recently completed and unpublished clinical trials meeting the inclusion criteria described were searched for from the following research registers: National Institutes of Health clinical trials registry (USA); National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network Portfolio Database (UK); National Research Register Projects Database Archive (UK); and Current Controlled Trials (includes the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register).

Study screening and selection

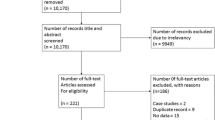

Titles and abstracts of studies retrieved using the search strategy and those from additional sources were screened independently by two review authors (KB and PK) to identify studies that potentially met the inclusion criteria. The full text of these potentially eligible studies was retrieved where possible and independently assessed for eligibility by two review authors. Any disagreement between the two review authors over the eligibility of particular studies was resolved through discussion with a third review author (CF). A summary of the data collection process is illustrated in the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses) Flow Diagram (Fig. 1). Additonally the authors prepared the PRISMA 2009 Checklist (Additional file 1).

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram [40]

Data, quality criteria and data analysis

Two reviewers independently extracted data on the number of randomised participants, intervention, intervention components, behavioural theory informing the intervention, mobile technology employed (e.g. mobile phone/ smartphone), media used (e.g. SMS, Voice message, MMS, application software, telephone), sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessors, completeness of follow up, evidence of selective outcome reporting, contamination, any other potential sources of bias and on measures of effect using a standardised data extraction form. The authors were not blind to authorship, journal of publication or the trial results. All discrepancies were agreed by discussion with a third reviewer. The behaviour change techniques employed in behaviour change interventions were classified according to Michie’s taxonomy of behaviour change techniques [18]. Risk of bias was assessed according to the Cochrane risk of bias tool. We assessed blinding of outcome assessors and data analysts and we used a cut off of 90 % complete follow up for low risk of bias for completeness of follow up. We contacted study authors for additional information about the included studies, or for clarification of the study methods as required.

All analyses were conducted in STATA v 11. We calculated risk ratios. We planned to use random effects meta-analysis to give pooled estimates where there were two or more trials employing the same mobile technology media (e.g. sms messages) and reporting the same outcome.

Results

The combined search strategies identified 958 eligible records that were screened for inclusion in the study. Of the 14 potentially eligible studies, 12 full papers and two abstracts were obtained. Of these, ten studies met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The abstract Lim et al. [19] included in Free et al. (2013) [7] review was excluded when the full paper Lim et al. (2012) revealed the intervention group received email and SMS. Similarly, Jones et al. [20] was published in full as Jones et al. [21], with the latter used in this review. Of the ten included trials, there were three intervention categories: 1) promotion of uptake of sexual health services, including reminders to attend a clinic 2) reduction of risky sexual behaviours and 3) reduced recall bias in reporting sexual activity.

Participants & characteristics of studies

The 10 trials included 16773 participants. Samples ranged from 52 to 7606 participants. Seven trials used a 2-arm design, two a 3-arm and one a 5-arm trial. All trials sought to address STI related issues with two studies focusing on increasing the uptake of testing [22, 23]; two focused on clinic re-attendance [24, 25]; four focused on risk reduction through sexual behaviour change [26–28] one focused on knowledge acquisition and risk reduction through sexual behaviour change [29] and one focused on reducing the recall bias when reporting sexual activity [30]. Trials were conducted in high and low-income countries with at-risk populations.

Interventions

The interventions are described in Table 1–4. For the two studies focusing on increasing the uptake of STI testing one used informational and motivational SMS [22], while the other used a video on a mobile device versus the standard paper-based protocol [23]. SMS reminders were used for the clinic re-attendance trials [24, 25]; one with and without financial incentives [24]. Risk reduction through behaviour change was trialed using SMS [26], video versus SMS [21], informational SMS [27] and informational SMS with theory based feedback and goal setting [28]. One trial focused on knowledge acquisition and risk reduction through behavior change used SMS designed for the target population [29]. Finally, one data collection study compared SMS to paper-based and online collection of sexual health information [30]. The maximum number of behavior change techniques employed in interventions was four, the median number of behavior change techniques employed was two. Three interventions reported being developed based on behavioral theory.

Comparisons

Heterogeneity in interventions and trial outcome assessment and reporting did not allow for meta-analysis.

Outcomes

The trials reported between one and five outcomes. For primary outcomes, two trials reported outcomes related to clinic attendance [24, 25]. One trial reported uptake of sexual health services [23]. There was also a trial that reported timeliness, completeness and response rate for the use of SMS to collect sexual health information [30]. In regards to secondary outcomes, one trial reported uptake of HIV counselling and testing [22]. Condom use was a common outcome measured among three of the four risk reduction trials [21, 28, 29]. In addition, sexual health knowledge and recent STI testing were also measured [29]. Furthermore, early resumption of sexual activity post circumcision was also reported in one risk reduction trial [27]. Four studies reported measures of acceptability of their interventions [26, 21, 28, 30].

Study quality

The assessment of study quality is reported in Table 5. No trial had a low risk of bias for all quality criteria.

Effects

We report the risk ratios for primary outcomes and secondary outcomes. See Tables 6 and 7.

Uptake of use of sexual health services including increasing testing and clinic re-attendance

Primary outcomes

Two trials showed statistically significant increases in clinic attendance in participants receiving clinic reminder SMS compared to controls [24, 25]. Odeny et al. [25] noted a significant decrease in patients that failed to return for a clinic visit (intervention group were more likely to return) after male adult circumcision, relative risk (RR) 0.86, 95 % confidence interval (CI) 0.74–1.00. Downing et al. [24] showed that SMS reminders quadrupled re-testing for Chlamydia compared to controls (RR 4.5, 95 % CI 1.05–19.22). SMS reminder plus incentives had a similar effect as SMS reminders alone. Shahkolahi [23] conducted a 2-arm trial to improve rapid HIV testing in a hospital Emergency Department using videos, a mobile application and paper-based intervention. The authors reported that there was a statistically significant increase in uptake of HIV testing among intervention participants exposed to the mobile application, however, a full paper was not available for this study and risk ratios could not be calculated.

Secondary outcomes

One 5-arm trial compared the use of motivational or informational SMS to improve uptake of HIV counselling and testing [22]. Intervention participants either received 3 or 10 motivational/informational SMS. Receipt of informational SMS was not associated with a statistically significant increase in uptake of HIV counseling (RR 0.94, 95 % CI 0.81–1.09 and RR 1.02, 95 % CI 0.89–1.17 for 3 and 10 SMS respectively). However, study participants who received either 3 or 10 motivational SMS were less likely to take up HIV counseling and testing (RR 0.86, 95 % CI 0.73–1.00 and RR 0.8, 95 % CI 0.69–0.93 for 3 and 10 SMS respectively).

Reduction of risky sexual behaviours including knowledge acquisition and behaviour change

Primary outcomes

There were no studies that reported primary outcomes in relation to reduction of risky sexual behaviours.

Secondary outcomes

None of the four trials showed statistically significant changes in sexual health behaviours. Gold et al. [29] explored the use of SMS to increase sexual health knowledge and intervention participants scored significantly better in their sexual health knowledge test (RR 1.75, 95 % CI 1.11–2.77) compared to the control group. There were no statistically significant changes in ‘always using condoms in the past 6 months’, (RR 0.87, 95 % CI 0.62–1.24).

Jones et al. [21] compared the effectiveness of HIV prevention messages delivered to smartphones either as weekly messages or through a soap opera video format over a 12-week period. There were no reported statistically significant differences between the two approaches (p = 0.39), although reductions in self-reported risky sexual behaviour (p <0.001) were reported in each arm compared to baseline at 3 and 6 months’ post intervention. Participants in the trial wanted to continue to receive the videos and reported they could relate to the characters.

Odeny et al. [27] assessed the impact of an SMS intervention to deter early resumption of sexual activity among men who had recently been circumcised. The authors did not find a statistically significant association between receipt of SMS and early resumption of sexual activity (RR 1.13, 95 % CI 0.91–1.38).

Suffoletto et al. [28] investigated the effect of an SMS intervention program to reduce risky sexual behaviour among young women attending an emergency department. No statistically significant differences between intervention and control arms were found for condom use with last vaginal sex (RR 1.4, 95 % CI 0.68–2.88) or for condom use with vaginal sex in the past 28 days (RR 1.4, 95 % 0.49–4.00). In terms of acceptability of the intervention, of the participants who completed the 3-month follow up, all stated that they found the SMS “very informative and very useful.”

Delamere et al. [26] assessed the effect of a 3-month SMS intervention to improve condom usage among young people attending a young person’s clinic. Participants in the intervention group were reported to be almost four times as likely as controls to have changed sexual partner during the study period (RR 3.65, 95 % CI 0.95–14.05), and twice as likely to have unprotected sex, (RR 2.03, 95 % CI 0.47–8.81), but neither result was statistically significant. In terms of acceptability, among intervention participants who were interviewed, 87.5 % reported the text messages useful in their decision making to use condoms, with 19 % of the cohort forwarding SMS to friends. All messages were rated as good, very good or excellent.

Sexual health data collection to reduce the recall bias when reporting sexual activity

Primary outcomes

Lim et al. [30] assessed three methods of sexual health data collection: paper, SMS and online diaries. They found that of the diaries submitted, 80 % of SMS diaries were submitted on the correct day in comparison to 63 % of online diaries.

Secondary outcomes

Lim et al. [30] reported 14 measures of acceptability comparing SMS, online and paper diary collection, of which 13 were not statistically significant. The sole statistically significant measure demonstrated that participants were more likely to be uncertain about completing SMS diaries compared to online diaries (p = 0.047).

Finally, no subgroup analyses were conducted due to the low number of included studies in this review.

Discussion

Key findings

Our systematic review of randomised controlled trials identified 10 RCTs (nine unique study groups) of interventions delivered by mobile technology to improve uptake of services and safer sex behaviours. None of the trials were at low risk of bias. Interventions contained few behavioral change techniques (up to five) and only a third of trials utilised any behaviour change theory in the design of their intervention. Three trials of interventions delivered by mobile phone messaging reported increased uptake of clinic appointments or STI testing. One trial reported increases in knowledge with an intervention delivered by mobile phone messaging. Among the four trials targeting a reduction in risky sexual behaviour, one showed promising increases in condom use, but the trial was small and the findings were not statistically significant. The use of mobile tools to collect sexual health information was shown to be both acceptable, and completed in a timely manner. Small sample sizes of some trials meant they were underpowered to detect effects.

Strengths and limitations of the review

Our systematic review employed a comprehensive search strategy and we searched 6 data bases and trial registries. Two researchers independently screened abstracts and extracted data from included studies regarding risk of bias and effect estimates. Despite calls for greater rigor in mHealth evaluation in 2008 [31], to date most known reviews have not exclusively focused on randomised studies or applied the Cochrane risk of bias [14, 32]. Our review updates earlier systematic reviews and is the first review focusing on safer sex to describe the content of interventions in terms of the behavioural theories and behaviour change techniques employed [7, 15]. A weakness of this systematic review is that due to the low number of trials reporting similar outcomes and heterogeneity of reporting it was not feasible to calculate pooled effect estimates. Furthermore, it was not possible to perform subgroup analyses due to the low number of included studies. However, as the rate of publication of studies in this area is increasing over time, a future review may be able to overcome this current limitation.

Discussion of the findings in relation to the existing literature and meaning of findings

This study, in agreement with a previous systematic review, shows that interventions delivered by mobile technology may provide modest benefits in terms of increasing safer sex behaviours carried out by individuals such as increasing clinic attendance and STI testing [7, 8]. It remains unclear if interventions delivered by mobile phone influence safer sex behaviours carried out between couples such as partner notification or condom use. There is a large body of existing research describing a wide range of individual, interpersonal and social and cultural factors influencing (safer) sexual behaviours [33], yet only one intervention delivered by mobile phone aimed to target these influences [21]. Existing face-to-face safer sex interventions which have reported reductions in sexually transmitted infections in randomised controlled trials include up to 19 behaviour change techniques (mean of 12 behaviour change techniques [34–38], whilst the interventions delivered by mobile phone in this review only included up to five behaviour change techniques. The limited number of factors influencing safer sex targeted by interventions, limited use of behavioral theory and limited number of behaviour change techniques employed in interventions are likely to be contributing to the lack of statistically significant findings in trials conducted to date.

Conclusion

The promising results of improved attendance at clinic appointments due to SMS reminders need to be confirmed in high quality trials. Using standardised objective measures, such as sexually transmitted infection rates, would allow meta-analysis and improve the assessment of any effects of mHealth interventions for sexual health. Studies are needed in low and middle income countries. While mobile phone coverage across the African continent and in many lower and middle-income countries holds promise for delivery of sexual health and other interventions, they remain underrepresented in terms of the quantity of trials conducted.

Additionally, most mHealth interventions are aimed at young populations despite evidence of older populations experiencing an increase in STI transmission [39] and thus future strategies should also consider this group. The results of ongoing trials of safer sex interventions which target a wider range of barriers to safer sex and employ a wider range of behaviour change techniques are needed to determine if interventions delivered by mobile phone can alter behaviours carried out between couples such as partner notification or condom use [34, 35].

Abbreviations

HBV, hepatitis B virus; HIV/AIDS, human immunodeficiency virus / acquired immune deficiency syndrome; mHealth, mobile health; SMS, short message service; STIs, sexually transmitted infections; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America; USD, United States Dollar

References

Grodstein F, Goldman MB, Cramer DW. Relation of tubal infertility to history of sexually transmitted diseases. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137(5):577.

Stanberry LR, Rosenthal SL. Sexually transmitted diseases: vaccines, prevention, and control. Oxford: Academic; 2013.

Report on global sexually transmitted infection surveillance 2013. World Health Organistion. Geneva: United Nations; 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112922/1/9789241507400_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 28 Jan 2016

Newman L, Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Wijesooriya NS, Unemo M, Low N, Stevens G, Gottlieb S, Kiarie J, Temmerman M. Global estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections in 2012 based on systematic review and global reporting. PloS One 2015;10(12). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143304

GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age–sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;385(9963):117–171.

Incidence, prevalence, and cost of sexually transmitted infections in the United States. In: CDC Fact Sheet. Centre for Disease Control (USA). 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats/sti-estimates-fact-sheet-feb-2013.pdf. Accessed 28 Jan 2016.

Free C, Phillips G, Galli L, Watson L, Felix L, Edwards P, Patel V, Haines A. The effectiveness of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2013;10(1):e1001362.

Free C, Phillips G, Watson L, Galli L, Felix L, Edwards P, Patel V, Haines A. The effectiveness of mobile-health technologies to improve health care service delivery processes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10(1):e1001363.

eHealth and innovation in women’s and children’s health: a baseline review. WHO & International Telecommunications Union. 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/111922/1/9789241564724_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 Accessed 28 Jan 2016.

Della MV. What is e-health: the death of telemedicine? J Med Internet Res. 2001;3(2):E22.

Sanou B. ICT facts and figures: the world in 2015. International Telecommunication Union. 2015. http://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/facts/ICTFactsFigures2015.pdf Accessed 28 Jan 2016.

mHealth. New horizons for health through mobile technologies: second global survey on eHealth. In: Global Observatory for eHealth.World Health Organisation. 2011. http://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_mhealth_web.pdf Accessed 28 Jan 2016.

Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, Kariri A, Karanja S, Chung MH, Jack W, Habyarimana J, Sadatsafavi M, Najafzadeh M. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376(3):1838–45.

Catalani C, Philbrick W, Fraser H, Mechael P, Israelski DM. mHealth for HIV treatment & prevention: a systematic review of the literature. Open AIDS J. 2013;7:17.

van Velthoven MH, Brusamento S, Majeed A, Car J. Scope and effectiveness of mobile phone messaging for HIV/AIDS care: a systematic review. Psychol Health Med. 2013;18(2):182–202.

Lunny C, Taylor D, Memetovic J, Wärje O, Lester R, Wong T, Ho K, Gilbert M, Ogilvie G. Short message service (SMS) interventions for the prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2014;3(1):7.

Free C, Phillips G, Felix L, Galli L, Patel V, Edwards P. The effectiveness of M-health technologies for improving health and health services: a systematic review protocol. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3(1):250.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles MP, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95.

Lim MSC, Hocking JS, Aitken CK, Jordan L, Fairley CK, Lewis JA, Hellard ME: A randomized controlled trial of the impact of email and text (SMS) messages on the sexual health of young people. SEXUAL HEALTH 2007, 4(4):290–290.

Jones R. Soap opera video on handheld computers to reduce young urban women's HIV sex risk. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12:876–884.

Jones R, Hoover DR, Lacroix LJ. A randomized controlled trial of soap opera videos streamed to smartphones to reduce risk of sexually transmitted human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in young urban African American women. Nurs Outlook. 2013;61(4):205–15. e203.

de Tolly K, Skinner D, Nembaware V, Benjamin P. Investigation into the use of short message services to expand uptake of human immunodeficiency virus testing, and whether content and dosage have impact. Telemed J E Health. 2012;18(1):18–23.

Shahkolahi MM, Wilson A, Zucker L. Mobile-application-based HIV intervention: an opt-in approach to promote rapid HIV screening in an inner-city emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;1:S95.

Downing SG, Cashman C, McNamee H, Penney D, Russell DB, Hellard ME. Increasing chlamydia test of re-infection rates using SMS reminders and incentives. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(1):16–9.

Odeny TA, Bailey RC, Bukusi EA, Simoni JM, Tapia KA, Yuhas K, et al. Text messaging to improve attendance at post-operative clinic visits after adult male circumcision for HIV prevention: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e43832. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0043832.

Delamere S, Dooley S, Harrington L, King A, Mulcahy F. Safer sex text messages: evaluating a health education intervention in an adolescent population. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82:A7–A28.

Odeny TA, Bailey RC, Bukusi EA, Simoni JM, Tapia KA, Yuhas K, Holmes KK, McClelland RS. Effect of text messaging to deter early resumption of sexual activity after male circumcision for HIV prevention: a randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(2):e50–7. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a0a050.

Suffoletto B, Akers A, McGinnis KA, Calabria J, Wiesenfeld HC, Clark DB. A sex risk reduction text-message program for young adult females discharged from the emergency department. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(3):387–93.

Gold J, Aitken CK, Dixon HG, Lim MS, Gouillou M, Spelman T, et al. A randomised controlled trial using mobile advertising to promote safer sex and sun safety to young people. Health Educ Res. 2011;26(5):782–94.

Lim MSC, Sacks-Davis R, Aitken CK, Hocking JS, Hellard ME. Randomised controlled trial of paper, online and SMS diaries for collecting sexual behaviour information from young people. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64:885–9. doi:10.1136/jech.2008.085316.

Lim MS, Hocking JS, Hellard ME, Aitken CK. SMS STI: a review of the uses of mobile phone text messaging in sexual health. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19(5):287–90.

Guse K, Levine D, Martins S, Lira A, Gaarde J, Westmorland W, Gilliam M. Interventions using new digital media to improve adolescent sexual health: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(6):535–43. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.03.014.

Marston C, King E. Factors that shape young people’s sexual behaviour: a systematic review. Lancet. 2006;368:1581–6.

Free C, Roberts IG, Abramsky T, Fitzgerald M, Wensley F. A systematic review of randomised controlled trials of interventions promoting effective condom use. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(2):100–10.

Free C, McCarthy O, French R, Wellings K, Roberts I, Edwards P, Bailey J, Devries K, Michie SHart G, Baraitser P. Can text messages increase safer sex behaviours in young people: Intervention development and pilot trial. HTA report (in press 2016)

Boyer CB, Shafer MA, Shaffer RA, Brodine SK, Pollack LM, Betsinger K, et al. Evaluation of a cognitive-behavioral, group, randomized controlled intervention trial to prevent sexually transmitted infections and unintended pregnancies in young women. Prev Med. 2005;40(4):420–31.

Shain RN, Piper JM, Newton ER, Perdue ST, Ramos R, Champion JD, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a behavioral intervention to prevent sexually transmitted disease among minority women. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(2):93–100.

NIMH Multisite HIV Prevention Trial Group. The NIMH Multisite HIV Prevention Trial: reducing HIV sexual risk behavior. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Multisite HIV Prevention Trial Group. Science. 1998;280(5371):1889–94.

Tillman JL, Mark HD. HIV and STI testing in older adults: an integrative review. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(15–16):2074–95.

Prisma Flow Diagram. Prisma. 2009. http://prisma-statement.org/documents/PRISMA%202009%20flow%20diagram.pdf Accessed 28 Jan 2016.

Michie S, Abraham C. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008;27(3):379.

de Bruin M, McCambridge J, Prins JM. Reducing the risk of bias in health behaviour change trials: improving trial design, reporting or bias assessment criteria? A review and case study. Psychol Health. 2015;30(1):8–34. doi:10.1080/08870446.2014.953531.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Jane Falconer (LSHTM library staff) for advice on the initial search strategy. In addition, we would also like to thank Lambert Felix (LSHTM) for guidance on the search strategy and analyses.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

A PDF file of our data extraction is available as Attachment 1. It is not presented in the paper, however supports the results in the paper.

Authors’ contributions

CF provided the protocol. PK and KB ran the search, reviewed the abstracts and full papers. PK performed all statistical analyses. All authors contributed to determining the results. KB led the drafting of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and edited the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

An ethics application and consent to publish are not required for a systematic review which reports on previously published data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Kara Burns and Patrick Keating were joint co-authors.

Appendix

Additional file

Additional file 1:

PRISMA 2009 Checklist (DOC 65 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Burns, K., Keating, P. & Free, C. A systematic review of randomised control trials of sexual health interventions delivered by mobile technologies. BMC Public Health 16, 778 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3408-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3408-z