Abstract

Objective

To assess the effectiveness of Internet-based self-help interventions in treating depression in adolescents and young adults.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted across six databases, including PubMed, to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that satisfied the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. The intervention measure consisted of Internet-based self-help interventions.

Results

A total of 23 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included in this analysis. Meta-analysis indicated that Internet-based self-help therapies significantly reduced depression scores in adolescents and young adults. (OR = -0.68, 95%CI [-0.88, -0.47], P < 0.001). We examined the effects of patient recruitment from various regions, medication usage, therapist involvement, weekly intervention time, and intervention duration. Patients selected from school, primary healthcare centers, clinics and local communities had better results. Intervention lasting 30 to 60 min and 60 to180 minutes per week were effective in the short term.

Conclusion

The internet-based self-help intervention can be effective in treating depression in adolescents and young adults. However, factors such as patient recruitment locations, medication usage, Therapists’ involvement, weekly intervention time, and intervention duration interacted with the outcome. Subgroup analysis on potential adverse effects and gender was impossible due to insufficient data from the included studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Depression is a prevalent mental illness characterized by depressed mood and lack of interest along with low self-esteem, distress, pessimism, and thoughts about suicide [1]. Depression prevalence is increasing in teenagers and young adults [2, 3]. Though traditional face-to-face psychotherapy is the recommended treatment [4], there are numerous challenges - the shortage of qualified professional doctors and psychotherapists and treatment expenses [5]. Since adolescents are competent users of the Internet [6], Internet-based self-help interventions can be more helpful for them due to flexible scheduling, freedom from geographical and traffic limits, and improved privacy [7, 8]. Prior research has shown the positive impact of self-help interventions on mental disorders [9].

10,11,12Nevertheless, these studies are old and concentrated on cognitive-behavioral approaches utilizing paper-based mediums, such as self-help manuals in print form, rather than internet-based self-help interventions. There is a growing body of research examining the effectiveness of internet-based interventions in reducing depressive symptoms. These studies have primarily focused on adults.

The rate of depression differs across different age groups. In childhood, the prevalence is less than 3% [13], rising to 14% during adolescence [14] and then to 17% in young adults [15], and then remain stable. It is essential to give more attention to the adolescent and young adult populations due to the increased vulnerability to depression in their formative years. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted to explore Internet-based self-help interventions for depression, but results have been inconsistent [16,17,18].

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we aimed to investigate the effectiveness of Internet-based self-help interventions on depression in adolescents and young adults. We also conducted subgroup analyses to investigate the factors that influence the effectiveness of Internet-based self-help interventions. These analyses were stratified based on patient recruitment locations, medication use, therapist involvement, weekly intervention time, and durations.

Materials and methods

Source of literature and screening

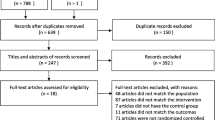

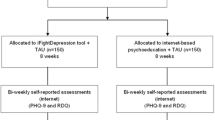

This study was conducted using the guidelines set by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA). Our study protocol has been registered in PROSPERO. A comprehensive search was conducted in several English databases, namely PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, Web of Science, CINAL, and SCOPUS. In accordance with the research inclusion criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Collaboration Network System Evaluators (version 5.0.2), the search results from various databases were imported into the literature management program Endnote 9.2. Afterwards, two researchers independently reviewed the literature and cross-checked their findings. Disagreements between them were resolved through the input of a third researcher. After excluding duplicates in the retrieved literature, the titles and abstracts of the remaining studies were screened to eliminate irrelevant studies. Following the initial screening, the complete texts of the remaining studies were reviewed to eliminate any irrelevant studies. Figure 1 displays the study screening flowchart. The data extracted from studies that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were entered into Excel 2019. The information included the first author, publication year, study area, average age, sample size, intervention measure, intervention site, control measure, diagnostic criteria, baseline symptoms, measurement scales, course of treatment, and risk of bias assessment. For studies not reporting the results, the corresponding authors were contacted to acquire more information.

Search strategies

A comprehensive search was conducted in databases such as PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, Web of Science, CINAL, and SCOPUS, covering the period from January 1788 to June 17, 2024. The enrolled RCTs were processed in line with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The subject term and free word search strategies were as follows: ((((“Adolescent“[Mesh]) OR ((((((((((((((((Adolescents[Title/Abstract]) OR (Adolescence[Title/Abstract])) OR (Teens[Title/Abstract])) OR (Teen[Title/Abstract])) OR (Teenagers[Title/Abstract])) OR (Teenager[Title/Abstract])) OR (Youth[Title/Abstract])) OR (Youths[Title/Abstract])) OR (Adolescents, Female[Title/Abstract])) OR (Adolescent, Female[Title/Abstract])) OR (Female Adolescent[Title/Abstract])) OR (Female Adolescents[Title/Abstract])) OR (Adolescents, Male[Title/Abstract])) OR (Adolescent, Male[Title/Abstract])) OR (Male Adolescent[Title/Abstract])) OR (Male Adolescents[Title/Abstract]))) OR ((“Young Adult“[Mesh]) OR (((Adult, Young[Title/Abstract]) OR (Adults, Young[Title/Abstract])) OR (Young Adults[Title/Abstract])))) AND ((“Internet-Based Intervention“[Mesh]) OR ((((((((((((((((Internet Based Intervention[Title/Abstract]) OR (Internet-Based Interventions[Title/Abstract])) OR (Intervention, Internet-Based[Title/Abstract])) OR (Interventions, Internet-Based[Title/Abstract])) OR (Web-based Intervention[Title/Abstract])) OR (Intervention, Web-based[Title/Abstract])) OR (Interventions, Web-based[Title/Abstract])) OR (Web based Intervention[Title/Abstract])) OR (Web-based Interventions[Title/Abstract])) OR (Online Intervention[Title/Abstract])) OR (Intervention, Online[Title/Abstract])) OR (Interventions, Online[Title/Abstract])) OR (Online Interventions[Title/Abstract])) OR (Internet Intervention[Title/Abstract])) OR (Internet Interventions[Title/Abstract])) OR (Interventions, Internet[Title/Abstract])))) AND ((“Depression“[Mesh]) OR (((((Depressive Symptoms[Title/Abstract]) OR (Depressive Symptom[Title/Abstract])) OR (Symptom, Depressive[Title/Abstract])) OR (Emotional Depression[Title/Abstract])) OR (Depression, Emotional[Title/Abstract]))). No language restriction was applied.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: ① studies on adolescents or young adults, 13 to 25 years ②. Studies on adolescents or young adults diagnosed with depression made based on the depression scale screening or by clinicians. ③ The intervention measure was Internet-based self-help interventions. Combined with previous studies, self-help interventions were described as the capacity of individuals to independently utilize written materials or multimedia resources via the internet or application (APP) to engage in relevant activities. The goal of self-help interventions should be related to psychological counseling or clinical psychology ④. The control group received either conventional treatment or was on a wait list for treatment. ⑤ The depression scale score was reported ⑥. Original data were complete, from which data regarding the depression prevalence rate could be extracted ⑦. The enrolled studies were RCTs.

Exclusion criteria: ① Studies with low quality and unavailable original data; ② meetings and unfinished clinical trials; ③ systematic reviews and meta-analyses; and ④ non-RCTs were excluded.

Outcome indicators

In this study, 24 RCTs were included. Depressive symptoms were measured using depression scales before and immediately after the intervention, and during follow-up after the intervention. The depression scales used included the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [19], the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [20], the Children’s Depression Rating Scale Revised (CDRS) [21], and the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) [22]. Also, the study evaluated the efficacy of Internet-based self-help interventions for depression by considering different factors such as the country where the intervention took place, the location where participants were recruited, whether they were taking medication, the involvement of professionals in the intervention, the duration of the intervention per week, and the overall intervention period.

Statistical analysis and quality evaluation

In this study, the Review Manager was used for statistical analysis. For continuous variables, the standardized mean differences (SMD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were obtained for analysis. Heterogeneity was evaluated by I2 statistics, with I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% indicating low, moderate, and high heterogeneities, respectively. The random-effects model was applied in summarizing the measurements in all studies. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Cochrane bias risk assessment tool was utilized to appraise the quality of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), encompassing six criteria: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, patient blinding, outcome assessor blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other forms of bias. According to the Cochrane Handbook’s recommendation, each item’s risk of bias was assessed and categorized as low, high, or ambiguous. The summary of bias analysis is depicted in Fig. 2.

Results

Effectiveness of internet-based self-help interventions for depression in adolescents and young adults

23 studies were included in the analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of Internet-based self-help interventions for depression in adolescents and young adults. The results of the meta-analysis revealed a significant level of variation (P < 0.01, I2 = 88%). The findings indicate that the depression scale scores in the group receiving Internet-based self-help interventions were notably lower compared to the pre-intervention (n = 3833, 23 RCTs, OR = -0.68, 95%CI [-0.88, -0.47], P < 0.001), as displayed in Fig. 3.

The efficacy among adolescents and young adults from different recruitment locations

The efficacy of Internet-based self-help interventions in patients recruited from distinct locations was observed by extracting recruitment locations from enrolled studies. This allowed for an assessment of these interventions’ impact on individuals from various places.

Figure 4 demonstrated that the patients selected from school, primary healthcare centers, clinics and local communities exhibited significantly reduced depression levels in the group receiving Internet-based self-help interventions. (recruitment from school: n = 2637, 13 RCTs, OR = -0.35, 95%CI [-0.43, -0.27], P < 0.01; recruitment from primary healthcare centers: n = 541, 3 RCTs, OR = -0.57, 95% CI [-0.75, -0.39], P < 0.01; recruitment from clinics: n = 328, 3 RCTs, [OR = -0.90, 95% CI [-1.13, -0.68], P < 0.01; recruitment from community: n = 125, 2 RCTs, OR = -1.23, 95%CI [-1.62, -0.85], P < 0.01). However, there was no significant difference in depression patients recruited from multiple locations. (recruitment from multiple locations: n = 202, 2 RCTs, OR = -0.22, 95%CI [-0.50, 0.06], P = 0.12;).

The efficacy with the use of medication or the involvement of therapists

There was inconsistency regarding the use of medication or the involvement of therapists among the studies included. Therefore, as part of the Internet-based self-help interventions, a subgroup analysis was conducted to observe and evaluate the impact. This analysis focused on factors such as medication use and therapist involvement.

Based on the result of enrolled RCTs, Internet-based self-help interventions reduce the depression scores in depression patients, no matter whether medications (medication: n = 1195, 11 RCTs, OR = -96, 95%CI [-1.27, -0.66], P < 0.01; no medication: n = 2020, 8 RCTs, OR = -0.12, 95%CI [-0.21, -0.04], P > 0.05]) or therapists were involved (therapists: n = 2278, 17 RCTs, OR = -0.76, 95%CI [-1.01, -0.51], P < 0.01; no therapists: n = 1555, 6 RCTs, OR = -0.45, 95%CI [-0.76, -0.14, P < 0.01], as shown in Figs. 5 and 6.

The efficacy with different weekly intervention time

Among the included trials, weekly intervention time clearly affected Internet-based self-help interventions. We discovered that typically these interventions were carried out in modules with different weekly intervention duration. Thus, an estimation was made using the module content, and a subgroup analysis was performed to assess the effect of weekly intervention time on depression scores.

Based on the findings in Fig. 7, it is evident that the depression scores are reduced when individuals engage in weekly self-help interventions for a duration of 30–60 min and 60–180 min (30–60 min: n = 1065, 8 RCTs, OR = -0.96, 95%CI [-1.33, -0.59], P < 0.01; 60–180 min : n = 686, 6 RCTs, OR = -0.72, 95%CI [-1.13,-0.31], P < 0.01). However, there was no significant difference at other weekly intervention time among depression patients (< 30 min: n = 1385, 4 RCTs, OR = -0.63, 95%CI [-1.14, 0.12], P = 0.02; > 180 min: n = 571, 3 RCTs, OR = -0.16, 95% CI [-0.33, -0.00], P < 0.01).

The efficacy with different intervention duration

In the included studies, we found that the duration of the intervention affected the efficacy of Internet-based self-help therapies. The studies were classified as short-term (< 24 weeks), medium-term (24–32 weeks), and long-term efficacy (> 32 weeks) based on previous research [23]. Thereafter, subgroup analyses were conducted to evaluate the efficacy of Internet-based self-help interventions over different intervention duration.

Figure 8 suggested that only the short-term efficacy of Internet-based self-help interventions reduced the depression scores (< 24 weeks: n = 4011, 23 RCTs, OR = -0.28, 95%CI [-0.43, -0.14], P < 0.01), while differences between the two intervention methods were not statistically significant among medium- or long-term intervention duration (24–32 weeks: n = 2086, 6 RCTs, OR = -0.06, 95%CI [-0.17, 0.06, P < 0.01]; > 32 weeks: n = 557, 3 RCTs, OR = -0.08, 95%CI [-0.44, 0.29, P > 0.01].

Discussion

This study included 23 articles [8, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45] for statistical analysis. Since the effect of Internet-based self-help interventions on depression symptoms was evaluated using different depression scales, we had to convert MD into SMD. Subsequently, subgroup analyses were performed using various scales. The study findings indicated that Internet-based self-help interventions effectively reduced depression scale scores in adolescents and young adults, which aligns with previous research [46, 47].

We conducted subgroup analyses to observe the differences in the efficacy of Internet-based self-help interventions across different variables. Firstly, regarding different recruitment locations of participants, Internet-based self-help interventions were observed to significantly lower depression scores among patients recruited from school, primary healthcare centers, clinics and local communities. However, there was no significant reduction in depression scores among patients recruited from multiple locations. This difference may be related to the complexity of the recruited population. Previous studies frequently involved non-clinical individuals, for example, schoolchildren, who usually have milder symptoms and lower depression ratings and are, therefore, more likely to respond effectively to interventions [48].

On the other hand, students recruited from schools may have a higher level of interest in experimenting with self-help interventions as substitutes for traditional treatments [47], increasing their willingness to accept and have confidence in these interventions. Secondly, we performed subgroup analyses to examine the impact of medication usage and therapist involvement on the intervention [49]. Based on the result of enrolled RCTs, Internet-based self-help interventions reduce the depression scores in depression patients, no matter whether medications or therapists were involved. The results suggested that Internet-based self-help interventions were often modularized through online platforms or mobile APPs. Therefore, we estimated the weekly self-help intervention time based on the module content. As a result, a weekly Internet-based self-help intervention time of 30–60 min and 60–180 min yielded the effective results. However, many of the included studies did not specifically state the precise weekly intervention period, which could include some degree of subjectivity in this study; this subjective element thus reduced the objectivity of the research results. In addition to the weekly intervention time, the studies included in this analysis were classified into different durations of efficacy: short-term (less than 24 weeks), medium-term (24–32 weeks), and long-term (more than 32 weeks). Our findings revealed the high short-term effectiveness of Internet-based self-help programs. Unlike earlier studies demonstrating notable short-, medium- and long-term efficacy [23], there was no appreciable variation in medium- or long-term efficacy here. Furthermore, some researchers have found the negligible short- and long-term effectiveness of Internet-based self-help programs while the medium-term efficacy is noteworthy. Targeting anxiety disorders, however, there is no notable efficacy at any one moment [10]. Therefore, the efficacy of Internet-based self-help interventions at different time periods remains controversial. According to our analysis, the poor medium- and long-term efficacy reported in the studies could be attributed to small sample sizes and high attrition rates of long-term efficacy. Furthermore, it could be related to patients gradually forgetting their self-regulation abilities and knowledge after stopping the intervention, hence lacking consistent intervention effects.

Compared to traditional therapy, internet-based self-help can assist adolescent depression patients in understanding and managing symptoms, achieving the desired intervention effect [50]. Moreover, relative to conventional face-to-face treatment, self-help intervention measures are cheap, more universal, and can be provided to more patients [51]. Furthermore, Internet-based self-help therapies can be unrestricted by time, place, or the availability of professional physician resources. This allows patients to obtain more flexible interventions [50]. Moreover, internet-based self-help programs are likely more beneficial for the adolescent demographic. Adolescents have a high level of skill in using social media. Internet-based self-help interventions like animated games can offer more engaging and interactive content. Additionally, these interventions can effectively manage the treatment schedule for each patient through an online platform, provide personalized assistance, and help adolescents with low self-control complete their treatment [50]. Noteworthily, during a pandemic like COVID-19, it may be challenging for some patients to obtain regular, continuous, face-to-face psychological intervention due to the epidemic control needs [32, 51]. In this case, patients can obtain convenient and timely intervention through the Internet. All the studies included in this investigation were RCTs, decreasing the risk of risk analysis bias.

There were several limitations. Firstly, there was high heterogeneity in the included RCTs related to the different depression scales and the small sample size. The risk of bias was also a source of heterogeneity, which restricted the interpretation of our results in this review. Secondly, due to the limitations of data in the included RCTs, only the effectiveness of Internet-based self-help interventions for depression was addressed. The potential negative consequences of this intervention were not addressed. Significantly, new research has tackled this problem by integrating the Negative Effects Questionnaire (NEQ) [52]. Thirdly, this study did not involve sex differences. Depression is more prevalent in females and has a higher suicide rate in males [53]. The male and female participants were not enough for subgroup analysis. Moreover, the included study involved patients with mild or moderate depression, so the effect of depression severity on the outcome could not be determined.

To summarize, this study indicates that the internet-based self-help intervention is effective in treating depression in adolescents and young adults. After conducting subgroup analyses based on the population recruitment location, medication use, and therapist involvement, we observed better intervention outcomes among patients recruited from school, primary healthcare centers, clinics and local communities. The effectiveness of Internet-based self-help interventions for depression is unaffected by the involvement of medications or therapists. Additionally, we found that the optimal intervention time were 30–60 min and 60–180 min per week, and significant short-term efficacy was achieved. However, the medium- and long-term efficacy and other evaluation metrics require further validation through more extensive, well-designed studies.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript and supplementary information files.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Zonca V. Preventive strategies for adolescent depression: what are we missing? A focus on biomarkers. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2021;18:100385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbih.2021.100385. PMID: 34825234; PMCID: PMC8604665.

Oliffe JL, Rossnagel E, Seidler ZE, Kealy D, Ogrodniczuk JS, Rice SM. Men’s Depression and Suicide. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(10):103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1088-y. PMID: 31522267.

Thapar A, Eyre O, Patel V, Brent D. Depression in young people. Lancet. 2022;400(10352):617–631. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01012-1. Epub 2022 Aug 5. PMID: 35940184.

Moeini B, Bashirian S, Soltanian AR, Ghaleiha A, Taheri M. Examining the effectiveness of a web-based intervention for depressive symptoms in female adolescents: applying Social Cognitive Theory. J Res Health Sci. 2019;19(3):e00454. PMID: 31586376; PMCID: PMC7183555.

Friedman VJ, Wright CJC, Molenaar A, McCaffrey T, Brennan L, Lim MSC. The Use of Social Media as a persuasive platform to Facilitate Nutrition and Health Behavior Change in Young adults: web-based conversation study. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(5):e28063. https://doi.org/10.2196/28063. PMID: 35583920; PMCID: PMC9161050.

Ahuvia IL, Sung JY, Dobias ML, Nelson BD, Richmond LL, London B, Schleider JL. College student interest in teletherapy and self-guided mental health support during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Health. 2022 Apr 15:1–7. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2022.2062245. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35427460.

Rickhi B, Kania-Richmond A, Moritz S, Cohen J, Paccagnan P, Dennis C, Liu M, Malhotra S, Steele P, Toews J. Evaluation of a spirituality informed e-mental health tool as an intervention for major depressive disorder in adolescents and young adults - a randomized controlled pilot trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:450. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-015-0968-x. PMID: 26702639; PMCID: PMC4691014.

Farrand P, Woodford J. Impact of support on the effectiveness of written cognitive behavioral self-help: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(1):182–95. Epub 2012 Nov 23. PMID: 23238023.

Wu Y, Fenfen E, Wang Y, Xu M, Liu S, Zhou L, Song G, Shang X, Yang C, Yang K, Li X. Efficacy of internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Internet Interv. 2023;34:100673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2023.100673. PMID: 37822787; PMCID: PMC10562795.

Zhou X, Edirippulige S, Bai X, Bambling M. Are online mental health interventions for youth effective? A systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2021;27(10):638–666. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X211047285. PMID: 34726992.

Ma L, Huang C, Tao R, Cui Z, Schluter P. Meta-analytic review of online guided self-help interventions for depressive symptoms among college students. Internet Interv. 2021;25:100427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2021.100427. PMID: 34401386; PMCID: PMC8350612.

Cohen P, Cohen J, Brook J. An epidemiological study of disorders in late childhood and adolescence-II. Persistence of disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1993;34(6):869 – 77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610. 1993.tb01095. x. PMID: 8408372.

Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Ries Merikangas K. Mood disorders in children and adolescents: an epidemiologic perspective. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49(12):1002–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01129-5.

Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):8–19. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002.

Smith P, Scott R, Eshkevari E, et al. Computerized CBT for depressed adolescents: Randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2015;73:104–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.07.009.

Calear AL, Christensen H, Mackinnon A, Griffiths KM, O’Kearney R. The Youth Mood Project: a cluster randomized controlled trial of an online cognitive behavioral program with adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(6):1021–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017391.

O’Kearney R, Kang K, Christensen H, Griffiths K. A controlled trial of a school-based internet program for reducing depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(1):65–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20507.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 19911:385–401.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001. 016009606.x.

Poznanski EO, Mokros HB. Manual for the Children’s. Depression Rating Scale-Revised Western Psychological Services; 1996.

Steer RA, Clark DA, Beck AT, Ranieri WF. Common and specific dimensions of self-reported anxiety and depression: the BDI-II versus the BDI-IA. Behav Res Ther. 1999;37(2):183 – 90. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00087-4. PMID: 9990749.

Mamukashvili-Delau M, Koburger N, Dietrich S, Rummel-Kluge C. Long-term efficacy of internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy self-help programs for adults with Depression: systematic review and Meta-analysis of Randomized controlled trials. JMIR Ment Health. 2023;10:e46925. https://doi.org/10.2196/46925. PMID: 37606990; PMCID: PMC10481211.

O’Kearney R, Kang K, Christensen H, Griffiths K. A controlled trial of a school-based Internet program for reducing depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(1):65–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20507. PMID: 18828141.

Lintvedt OK, Griffiths KM, Sørensen K, Østvik AR, Wang CE, Eisemann M, Waterloo K. Evaluating the effectiveness and efficacy of unguided internet-based self-help intervention for the prevention of depression: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2013 Jan-Feb;20(1):10–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.770. Epub 2011 Sep 2. PMID: 21887811.

Moeini B, Bashirian S, Soltanian AR, Ghaleiha A, Taheri M. Examining the effectiveness of a web-based intervention for depressive symptoms in female adolescents: applying Social Cognitive Theory. J Res Health Sci. 2019;19(3):e00454. PMID: 31586376IF: 1.5; PMCID: PMC7183555.

Calear AL, Christensen H, Mackinnon A, Griffiths KM, O’Kearney R. The Youth Mood Project: a cluster randomized controlled trial of an online cognitive behavioral program with adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(6):1021-32. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017391. PMID: 19968379.

Hoek W, Schuurmans J, Koot HM, Cuijpers P. Effects of Internet-based guided self-help problem-solving therapy for adolescents with depression and anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(8): e43485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043485IF: 3.7 Q2. Epub 2012 Aug 31. PMID: 22952691; PMCID: PMC3432036.

Merry SN, Stasiak K, Shepherd M, Frampton C, Fleming T, Lucassen MF. The effectiveness of SPARX, a computerized self-help intervention for adolescents seeking help for depression: randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. BMJ. 2012;344:e2598. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e2598. PMID: 22517917; PMCID: PMC3330131.

Clarke G, Kelleher C, Hornbrook M, Debar L, Dickerson J, Gullion C. Randomized effectiveness trial of an Internet, pure self-help, cognitive behavioral intervention for depressive symptoms in young adults. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38(4):222 – 34. doi: 10.1080/16506070802675353IF: 4.7 Q1. PMID: 19440896; PMCID: PMC2829099.

pooco N, Berg M, Johansson S, et al. Chat- and internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy in treatment of adolescent depression: randomized controlled trial. BJ Psych Open. 2018;4(4):199–207. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2018.18. Published 2018 Jun 26.

Morr C, Ritvo P, Ahmad F, Moineddin R, MVC Team. Effectiveness of an 8-Week Web-Based Mindfulness Virtual Community Intervention for University Students on Symptoms of Stress, Anxiety, and Depression: Randomized Controlled Trial [published correction appears in JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(9):e24131]. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(7):e18595. Published 2020 Jul 17. https://doi.org/10.2196/18595

Stasiak K, Hatcher S, Frampton C, Merry SN. A pilot double blind randomized placebo-controlled trial of a prototype computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy program for adolescents with symptoms of depression. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2014;42(4):385–401. Epub 2012 Dec 20. PMID: 23253641.

Nicol G, Wang R, Graham S, Dodd S, Garbutt J. Chatbot-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy in adolescents with depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic: feasibility and acceptability study. JMIR Form Res. 2022;6(11):e40242. https://doi.org/10.2196/40242. PMID: 36413390; PMCID: PMC9683529.

Martínez V, Rojas G, Martínez P, Gaete J, Zitko P, Vöhringer PA, Araya R. Computer-assisted cognitive-behavioral therapy to treat adolescents with Depression in Primary Health Care Centers in Santiago, Chile: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:552. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00552. PMID: 31417440; PMCID: PMC6682617.

Ip P, Chim D, Chan KL, Li TM, Ho FK, Van Voorhees BW, Tiwari A, Tsang A, Chan CW, Ho M, Tso W, Wong WH. Effectiveness of a culturally attuned internet-based depression prevention program for Chinese adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(12):1123–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22554. Epub 2016 Sep 13. PMID: 27618799.

Topooco N, Byléhn S, Dahlström Nysäter E, Holmlund J, Lindegaard J, Johansson S, Åberg L, Bergman Nordgren L, Zetterqvist M, Andersson G. Evaluating the efficacy of internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy blended with synchronous Chat Sessions to treat adolescent depression: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(11):e13393. https://doi.org/10.2196/13393. PMID: 31682572; PMCID: PMC6858617.

Srivastava P, Mehta M, Sagar R, Ambekar A. Smartteen- a computer assisted cognitive behavior therapy for Indian adolescents with depression- a pilot study. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;50:101970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101970. Epub 2020 Feb 19. PMID: 32114331.

Grudin R, Ahlen J, Mataix-Cols D, Lenhard F, Henje E, Månsson C, Sahlin H, Beckman M, Serlachius E, Vigerland S. Therapist-guided and self-guided internet-delivered behavioral activation for adolescents with depression: a randomized feasibility trial. BMJ Open. 2022;12(12):e066357. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-066357. PMID: 36572500; PMCID: PMC9806095.

Dear BF, Fogliati VJ, Fogliati R, Johnson B, Boyle O, Karin E, Gandy M, Kayrouz R, Staples LG, Titov N. Treating anxiety and depression in young adults: a randomized controlled trial comparing clinician-guided versus self-guided internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2018;52(7):668–79. Epub 2017 Oct 24. PMID: 29064283.

Farrer LM, Gulliver A, Katruss N, Fassnacht DB, Kyrios M, Batterham PJ. A novel multi-component online intervention to improve the mental health of university students: Randomized controlled trial of the Uni virtual clinic. Internet Interv. 2019;18:100276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2019.100276. PMID: 31890625; PMCID: PMC6926241.

Gladstone T, Buchholz KR, Fitzgibbon M, Schiffer L, Lee M, Voorhees BWV. Randomized Clinical Trial of an internet-based adolescent Depression Prevention intervention in primary care: internalizing Symptom outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):7736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217736. PMID: 33105889; PMCID: PMC7660174.

Harrer M, Adam SH, Fleischmann RJ, Baumeister H, Auerbach R, Bruffaerts R, Cuijpers P, Kessler RC, Berking M, Lehr D, Ebert DD. Effectiveness of an internet- and App-Based Intervention for College Students with elevated stress: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(4):e136. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9293. PMID: 29685870; PMCID: PMC5938594.

Kählke F, Berger T, Schulz A, Baumeister H, Berking M, Auerbach RP, Bruffaerts R, Cuijpers P, Kessler RC, Ebert DD. Efficacy of an unguided internet-based self-help intervention for social anxiety disorder in university students: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2019;28(2):e1766. Epub 2019 Jan 27. PMID: 30687986; PMCID: PMC6877166.

Kramer J, Conijn B, Oijevaar P, Riper H. Effectiveness of a web-based solution-focused brief chat treatment for depressed adolescents and young adults: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(5):e141. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3261. PMID: 24874006; PMCID: PMC4062279.

Imai H, Tajika A, Narita H, et al. Unguided computer-assisted self-help interventions without human contact in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(4):e35940. https://doi.org/10.2196/35940. Published 2022 Apr 21.

Noh, Dabok P, Hyunjoo S, Mi-So. Website and Mobile Application-based interventions for adolescents and young adults with Depression: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Korean Acad Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2023;32(1):78–91. https://doi.org/10.12934/jkpmhn.2023.32.1.78.

Gellatly J, Bower P, Hennessy S, Richards D, Gilbody S, Lovell K. What makes self-help interventions effective in the management of depressive symptoms? Meta-analysis and meta-regression. Psychol Med. 2007;37(9):1217–28. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291707000062.

McCarron RM, Shapiro B, Rawles J, Luo J, Depression. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(5):ITC65-ITC80. doi: 10.7326/AITC202105180. Epub 2021 May 11. PMID: 33971098.

Melbye S, Kessing LV, Bardram JE, Faurholt-Jepsen M. Smartphone-based Self-Monitoring, treatment, and automatically generated data in children, adolescents, and young adults with Psychiatric disorders: systematic review. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(10):e17453. https://doi.org/10.2196/17453. Published 2020 Oct 29.

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8.

Zhou Y, Wang J. Internet-based self-help intervention for procrastination: randomized control group trial protocol. Trials. 2023;24(1):82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-023-07112-7. PMID: 36747265; PMCID: PMC9900198.

Garde K. Depression–kønsforskelle [Depression–gender differences]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2007;169(25):2422–5. Danish. PMID: 17594834.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the of the participants who have helped us with this project.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or nonprofit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Each author has made substantial contributions to the conception. Qian Ma and Dongmei Tan had designed of the work and the acquisition, analysis, Huixiang Zhang and Wei Zhao interpretatived the data; Congcong Ji and Lin Liu made the creation of new software used in the work; Qian Ma and Wei Zhao had drafted the work or substantively revised it. Congcong Ji assisted in the initial review by completing new database searches and literature screening. Zhao Wei contributed to language refinement and editing across multiple reviews, particularly enhancing clarity and conciseness in the results and discussion sections.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Jinan Preschool Education College and Universiti Malaya and Shandong Provincial Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital, and all participants provided informed consent. The study methodology was carried out following relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, Q., Shi, Y., Zhao, W. et al. Effectiveness of internet-based self-help interventions for depression in adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 24, 604 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-06046-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-06046-x