Abstract

Background

The prevalence of sleep disorders among medical students was high during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, fewer studies have been conducted on sleep disorders among medical students after the COVID-19 pandemic. This study investigated the prevalence and factors influencing sleep disorders among Chinese medical students after COVID-19.

Methods

A total of 1,194 Chinese medical students were included in this study from 9th to 12th July 2023. We used the Self-administered Chinese scale to collect the demographic characteristics. In addition, we used the Chinese versions of the Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS), the Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) to assess subjects’ depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders, respectively. The chi-square test and binary logistic regression were used to identify factors influencing sleep disorders. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was utilized to assess the predictive value of relevant variables for sleep disorders.

Results

We found the prevalence of sleep disorders among medical students after COVID-19 was 82.3%. According to logistic regression results, medical students with depression were 1.151 times more likely to have sleep disorders than those without depression (OR = 1.151, 95% CI 1.114 to 1.188). Doctoral students were 1.908 times more likely to have sleep disorders than graduate and undergraduate students (OR = 1.908, 95% CI 1.264 to 2.880).

Conclusion

The prevalence of sleep disorders among medical students is high after COVID-19. In addition, high academic levels and depression are risk factors for sleep disorders. Therefore, medical colleges and administrators should pay more attention to sleep disorders in medical students after the COVID-19 pandemic. Regular assessment of sleep disorders and depression is essential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

COVID-19, caused by a novel coronavirus that emerged in December 2019 [1], has profoundly impacted healthcare systems and populations worldwide [2,3,4]. With a case fatality rate ranging from 1 to 7%, the virus continues to exert long-term health effects on individuals even after recovery, commonly called post-COVID or long COVID-19 [2, 5, 6]. The extended consequences of COVID-19 extend to various organs and systems, posing a sustained threat to both physical and mental health [2, 4, 5, 7], with infection serving as a risk factor for exacerbating psychological disorders [8]. For example, some studies have found that long after infection with COVID-19, patients continue to experience sleep disorders, anxiety, and depression problems [9,10,11,12].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, medical students faced significant physical and mental stressors [13,14,15], including high workload and challenges due to insufficient protective measures [16]. The prevalence of sleep disorders among medical students during this period was notable [17, 18]. For instance, Greek medical students experienced severe disruptions in sleep quality during the pandemic, with the majority reporting insomnia (65.9%) and poor sleep quality (52.4%) [17]. A multinational cross-sectional survey reported that 73.5% of medical students had poor sleep quality during the pandemic [19]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis encompassing 201 studies found a prevalence of sleep disorder of 52% among medical students during the COVID-19 outbreak [20]. Sleep disorders persist in medical students even after the initial surge of the pandemic [21]. However, research on the prevalence of sleep disorders and influencing factors in medical student’s post-pandemic remains limited [22]. Therefore, timely and in-depth analysis of the health status of Chinese medical students is imperative. Identifying relevant factors is critical to developing effective intervention strategies.

It is crucial to study the mental health of medical students because China faces a critical issue of medical student attrition [23, 24], coupled with challenges such as limited job opportunities and declining public trust in doctors, leading to decreased identity of self [25], low-income [26], challenging work environments [27], and uneven distribution of medical resources [28]. During the COVID-19 outbreak, a survey found that 58.4% of respondents wanted to change their profession after graduation [29]. Therefore, research is urgently needed to explore Chinese medical students’ mental health status and identify relevant influencing factors to formulate effective interventions.

The impact of the pandemic on medical students’ mental health is enduring and requires long-term monitoring [2, 30]. Previous studies have found that the risk of sleep disorders remains elevated one year after significant events such as a pandemic [8]. Sleep disorders have many contributing factors, including anxiety and depression [31]. However, as far as we know, no previous study has explored sleep disorders in post-COVID-19 medical students. Thus, the objectives of the current research include: (1) To investigate the prevalence of sleep disorders among medical students two months after the COVID-19 outbreak. And (2) to explore the factors influencing sleep disorders in medical students after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study design and procedure

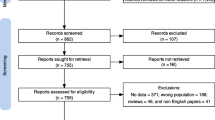

A total of 1194 medical students were recruited for this study from 9 to 20 July 2023 (as shown in Fig. 1). Before the poll began, we ensured that all participants had electronically given their informed consent. Participants needed to be able to read Chinese, understand the survey’s goals, be told, and agree to take part in the study for it to be considered. Refusal to participate in this study, more than 15% missing data, and inconsistent response completeness were exclusion criteria. After data collection was complete, two researchers double-checked the questionnaire for accuracy. The flowchart for this study is shown in Fig. 1.

The protocol for the research project had been approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Tianjin Anding Hospital (approving number: 2023-027). The research was carried out after the principles laid out in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later revisions. Confidentiality of responses was assured, and all participants gave their informed consent.

Tools and related issues

The Chinese versions of the SDS, SAS, and PSQI were used to assess subjects’ depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders, respectively. In addition, we used a general demographic questionnaire, which we designed, to collect the demographic characteristics of the subjects.

In the general demographic questionnaire, there was a question about “Financial pressure”: Are you feeling heavy financial pressure? The “Employment pressure” question: Are you feeling heavy employment pressure? The question of “Disruption of medical education”: Has the epidemic disrupted medical education? The question of “Wish to return to clinical rotation”: Do you wish to return on time? The question of “Pursuing clinical work after graduation”: Whether you want to pursue a clinical career after graduation? The question of “The impact of COVID-19”: What do you think about the impact of COVID-19 on healthcare? The question of “Worried about being infected”: Are you worried about infecting COVID-19 when you return to your clinical rotation?

Infection number of medical students with COVID-19

The well-known medical illness known as post-viral infection syndrome (PVIS) varies in severity after acute viral infection recovery. It is marked by different degrees of physical, cognitive, and emotional impairment [32]. For this reason, we divided the medical students into three groups according to the number of COVID-19 infections: 1, ≥ 2, and 0.

Demographic characteristics

Academic level, gender, birthplace, weekly exercise frequency, personality trait, health condition, being infected with COVID-19, in clinic rotation, financial pressure, employment pressure, disruption of medical education, wish to return to clinical rotation, pursuing clinical work after graduation, the impact of COVID-19 and worried about being infected were among the demographic characteristics listed. Each participant’s frequency of being infected with COVID-19 was evaluated using the following three-point dimensions: “1,” “≥2,” and “0.” Every participant was asked to rate the epidemic’s impact on their future medical careers on a three-point scale: “no impact,” “positive,” and “negative.”

Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI)

We used the Chinese version of the PSQI [2] to evaluate sleep disorders [33]. The 19-question questionnaire comprises seven sections: sleep duration, sleep disturbance, sleep latency, subjective sleep quality, habitual sleep efficiency, daytime dysfunction, and sleep medications. With a total of 21 points, the PSQI reflects the quality of each component. Participants in this study were classified as having a sleep disorder if their overall PSQI score was eight or above [34]. This scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.71 [35].

Self-rating anxiety scale (SAS)

We used the Chinese version of the SAS to assess anxiety symptoms [36]. Each symptom on the SAS questionnaire has a frequency scale from 1 to 4, comprising 20 items. After determining the raw score for each item, we multiplied it by 1.25 to get the standardized value. The SAS norm, which captures the subjective experiences of people who tend to stress out, was utilized to establish a cutoff threshold for anxiety at 50 points on a standardized scale [37]. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 was recorded for this scale [38].

Self-rating depression scale (SDS)

The Chinese version of the SDS, a brief 20-question questionnaire, measured depressive symptoms [39]. The validity and reliability of this lengthy self-administered survey are high. One can get an overall SDS score by adding the results from all 20 questions. To get the standardized score, multiply the SDS score by 1.25, keeping the whole value. The SDS norm, which represents the subjective experiences of individuals with depression, was utilized to establish a cutoff point for depression at 40 on the standardized total score [40]. The SDS has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.73 [41].

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 25.0. The use of descriptive analysis allowed for the characterization of demographic features. To display categorical data, we use the numbers N and %. In addition, to better understand the distribution characteristics and statistical properties of quantitative data, we use Mean, Standard Deviation (SD), Skewness, and Kurtosis to summarize quantitative data. Dissimilarities between medical students suffering from sleep disorders and those without were examined using a chi-square test.

Furthermore, binary logistic regression was employed to examine potential risk factors for sleep disorders, with all variables that were significant in the chi-square test serving as dependent variables. We used the enter-LR technique. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the ratio of ratios (OR) showed the degree to which different factors were linked to sleep disorders. For the test, a p-value less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Analyses were performed using the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC curve) to assess the predictive value of relevant variables for sleep disorders.

Results

Demographic characteristics of participants

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants. This study included approximately equal numbers of male (50.2%) and female (49.8%) participants. In addition, most medical students have been infected once (60.6%), and a few have been infected more than twice (29.3%) or have never been infected (10.1%) with COVID-19.

Clinical characteristics of participants

Table 2 shows the participants’ scores on the Chinese versions of SDS, SAS, and PSQI, including skewness and kurtosis. Of the seven components of the PSQI, the mean scores of subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep disturbance, the use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction were above 1. In addition, the mean scores for solely habitual sleep efficiency were less than 1 (Table 2).

Comparison of medical students with and without sleep disorders

Table 3 compares the differences between medical students with and without sleep disorders. Doctoral students were more likely to have sleep disorders than undergraduate and graduate students (χ2 = 19.594, P < 0.001). Interestingly, medical students who did not feel employment stress were more likely to have sleep disorders than those who felt employment stress (χ2 = 8.344, P = 0.004). However, there was no statistically significant difference between the number of times medical students had been infected with COVID-19 and the prevalence of sleep disorders (χ2 = 2.901, P = 0.235). Notably, medical students with depression (χ2 = 267.378, P < 0.001) and anxiety (χ2 = 46.489, P < 001) were more likely to have sleep disorders than those without depression and anxiety.

Risk factors of sleep disorders in medical students

We used binary logistic regression to explore the factors influencing sleep disorders among medical students after the epidemic (Table 4). The presence of a sleep disorder was used as the dependent variable, and variables with significant differences in univariate analyses were used as independent variables. The results found that depression was a risk factor for sleep disorders among medical students after the epidemic (OR = 1.151, 95% CI 1.114–1.188). In addition, academic level influenced sleep disorders among medical students (OR = 1.908, 95% CI 1.264–2.880). The area under the ROC curve for depression is 0.689 (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The current study is the first large-scale cross-sectional investigation to explore the prevalence of sleep disorders among medical students after the COVID-19 pandemic. Our main findings are as follows: first, the incidence of sleep disorders among medical students after the COVID-19 pandemic is 82.3%; second, academic level, health condition, employment pressure, and pursuing clinical work after graduation influence sleep disorders; and finally, depression and high educational level are independent risk factors of sleep disorders among medical students.

The main finding is that the prevalence of sleep disorders is 82.3% among medical students after the COVID-19 pandemic. This result aligns with previous research [42]. For instance, a meta-analysis shows that sleep disorders are prevalent in the medical student population [42]. Another study in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, found a 76% incidence of poor sleep quality among medical students [43]. However, the current study reveals a higher incidence of sleep disorders among medical students than earlier studies during COVID-19 [17, 20]. For example, a study in Greece found a sleep disorder incidence of 52.4% among medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic [17]. A systematic review and meta-analysis also reported a 52% incidence of sleep disorders among medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic [20]. However, most previous studies were conducted during the epidemic, whereas our study was conducted after the epidemic, which may have contributed to the difference in prevalence. In addition, we used the Chinese versions of the PSQI, SAS, and SDS scales. The cutoff values we set, the reliability of these scales, and the way participants responded to them may have differed from other studies. Therefore, it is necessary to consider these factors to understand the inconsistency of the study results more fully.

Furthermore, we found that the academic level influences sleep disorders among medical students after the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous studies have limited exploration of sleep disorder incidence among graduate students [44]. It is well known that there is a strong relationship between academic level and mental health [45]. Furthermore, it has been found that the higher the level of education, the higher the prevalence of sleep disorders [46]. For example, doctoral students had significantly higher levels of anxiety and sleep problems as well as depressive symptoms than master’s students in Polish [47]. In addition, one study in Hong Kong found that approximately 83% of graduate students experienced sleep disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic [44]. People with high academic levels sleep poorly due to high competitive pressure [47]. Our findings provide new literature on the relationship between educational levels and sleep disorders.

Another main finding of our study is that depression is an independent risk factor for sleep disorders among medical students after the COVID-19 pandemic. Depression is prevalent, costly, debilitating, and associated with an increased risk of suicide [48,49,50]. There is a close relationship between depression and sleep disorders [51, 52]. Most sleep disorder patients experience depressive episodes, and higher levels of depression are associated with an increased incidence of sleep disorders [53]. Hence, the relationship between depression and sleep disorders may be bidirectional [51, 52]. For instance, a meta-analysis found a positive correlation between depression and sleep disorders [54]. Studies have shown a higher incidence of depression in patients with sleep disorders [53]. The reasons depression affects sleep disorders include: Firstly, patients with depression have reduced circadian rhythm amplitude, and various treatments for depression have been shown to affect circadian rhythms [55]. Secondly, severe depressive disorders are associated with functional impairments in the structural network regulating rapid eye movement (REM) sleep [56]. Finally, the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) is a crucial region regulating depression and sleep, and significant changes in neural activity in the mPFC subregions of depression patients have been observed [57].

It is noteworthy that, before initiating this study, we predicted that infecting COVID-19 would affect the sleep disorders of medical students. Surprisingly, our study results indicate no difference in the incidence of sleep disorders among medical students infected once, more than two times, or not at all with COVID-19. This result may be attributed to China being one of the earliest countries to commence global COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, leading to a significant decline in COVID-19-related mortality rates [58]. Previous research in the United States suggests that repeated COVID-19 infections further increase the risks of death, hospitalization, and sequelae [59]. However, no studies examine the impact of recurrent infections and the number of infections on sleep disorders. Therefore, more studies are needed to investigate the effects of COVID-19 infection on sleep.

Despite providing valuable insights, our current study has limitations that must acknowledged. Firstly, the cross-sectional research limits our detailed understanding of how COVID-19 affects sleep disorders, so this study cannot conclude a causal relationship between COVID-19 and sleep disorders. Future research should employ longitudinal studies to understand the temporal effects of these results. Secondly, due to the online survey design, most studies used self-administered Chinese questionnaires without clinical diagnostic confirmation. However, all included studies used validated screening tools such as the Chinese versions of the SDS, SAS, and PSQI. Therefore, future research is recommended to use rigorous clinical diagnosis to confirm our results. Additionally, the assessment of personality traits is based on self-reports, which may introduce some bias. Future research could utilize personality assessment tools like the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI). Thirdly, the questionnaire did not include whether participants were isolated during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it remains unclear whether this would affect sleep disorders. Additionally, the current study only assessed medical students in China, and generalizing the results to the entire medical student population may be challenging. Finally, we used a sampling method in this study, so there may be issues with representativeness limitations. Future studies can further explore the underlying mechanisms and incidence rates.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the prevalence of sleep disorders among medical students after the COVID-19 pandemic is high. Additionally, depression and high academic levels are independent risk factors for sleep disorders among medical students. Thus, relevant organizations must develop targeted intervention strategies to reduce the incidence of sleep disorders among medical students after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability

Data availability statement: The raw data supporting this study’s findings are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Kevadiya BD, et al. Diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat Mater. 2021;20(5):593–605.

Higgins V, et al. COVID-19: from an acute to chronic disease? Potential long-term health consequences. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2021;58(5):297–310.

Chotpitayasunondh T, et al. Influenza and COVID-19: what does co-existence mean? Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2021;15(3):407–12.

Chatterjee AB. COVID-19, critical illness, and Sleep. Crit Care Med. 2022;50(6):1021–3.

Davis HE, et al. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21(3):133–46.

Su S, et al. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and management of long COVID: an update. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28(10):4056–69.

Zarei M, et al. Long-term side effects and lingering symptoms post COVID-19 recovery. Rev Med Virol. 2022;32(3):e2289.

Xie Y, Xu E, Al-Aly Z. Risks of mental health outcomes in people with covid-19: cohort study. BMJ. 2022;376:e068993.

Zawilska JB, Kuczyńska K. Psychiatric and neurological complications of long COVID. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;156:349–60.

Pandharipande P, et al. Mitigating neurological, cognitive, and psychiatric sequelae of COVID-19-related critical illness. Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11(8):726–38.

Hassanvandi S, Mohammadi MT, Shahyad S. Predicting the severity of COVID-19 anxiety based on sleep quality and mental health in healthcare workers. Novelty Clin Med. 2022;1(4):184–91.

Hasanvandi S, Saadat SH, Shahyad S. Predicting the possibility of post-traumatic stress disorder based on demographic variables, levels of exposure to Covid-19, Covid-19 anxiety and sleep quality dimensions in health care workers. Trauma Monthly. 2022;27(Especial Issue COVID–19 and Emergency Medicine):8–17.

Cao W, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112934.

Ma Z, et al. Mental health problems and correlates among 746 217 college students during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e181.

Stanyte A, et al. Mental Health and Wellbeing in Lithuanian Medical Students and Resident doctors during COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:871137.

Qian F, et al. Should Medical Students be overprotected? A Survey from China and Review about the roles of Medical Student under the COVID-19. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2023;16:327–35.

Eleftheriou A, et al. Sleep Quality and Mental Health of Medical Students in Greece during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2021;9:775374.

Chaabane S, et al. Sleep disorders and associated factors among medical students in the Middle East and North Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):4656.

Tahir MJ, et al. Internet addiction and sleep quality among medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multinational cross-sectional survey. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(11):e0259594.

Peng P, et al. The prevalence and risk factors of mental problems in medical students during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2023;321:167–81.

Pinzon RT, et al. Persistent neurological manifestations in long COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Public Health. 2022;15(8):856–69.

Cheng J, et al. Mental health and cognitive function among medical students after the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1233975.

Zeng J, Zeng XX, Tu Q. A gloomy future for medical students in China. Lancet. 2013;382(9908):1878.

Peng P, et al. High prevalence and risk factors of dropout intention among Chinese medical postgraduates. Med Educ Online. 2022;27(1):2058866.

Zhao D, Zhang Z. Changes in public trust in physicians: empirical evidence from China. Front Med. 2019;13(4):504–10.

Feng J, et al. The prevalence of turnover intention and influencing factors among emergency physicians: a national observation. J Glob Health. 2022;12:04005.

Gao X, Xu Y. Overwork death among doctors a challenging issue in China. Int J Cardiol. 2019;289:152.

Wu Q, Zhao L, Ye XC. Short Healthc Professionals China Bmj. 2016;354:i4860.

Cai CZ et al. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on Medical Student Career perceptions: perspectives from medical students in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021. 18(10).

Wang S, et al. Prevalence and influencing factors of sleep disturbance among medical students under the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci; 2023.

Difrancesco S, et al. Sleep, circadian rhythm, and physical activity patterns in depressive and anxiety disorders: a 2-week ambulatory assessment study. Depress Anxiety. 2019;36(10):975–86.

Lippi G, Sanchis-Gomar F, Henry BM. COVID-19 and its long-term sequelae: what do we know in 2023? Pol Arch Intern Med, 2023. 133(4).

Chen X, et al. Suicidal ideation and associated risk factors among COVID-19 patients who recovered from the first wave of the pandemic in Wuhan, China. QJM. 2023;116(7):509–17.

Ho RT, Fong TC. Factor structure of the Chinese version of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index in breast cancer patients. Sleep Med. 2014;15(5):565–9.

Yan DQ, et al. Application of the Chinese Version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in people living with HIV: preliminary reliability and validity. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:676022.

Wang Y, et al. Anxiety and depression in allergic rhinitis patients during COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan, China. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2022;40(3):210–6.

Dunstan DA, Scott N. Norms for Zung’s self-rating anxiety scale. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):90.

Du C, et al. Testing the validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the Staden schizophrenia anxiety rating scale. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:992745.

Ran MS, et al. The impacts of COVID-19 outbreak on mental health in general population in different areas in China. Psychol Med. 2022;52(13):2651–60.

Jokelainen J, et al. Validation of the Zung self-rating depression scale (SDS) in older adults. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2019;37(3):353–7.

Shi J, et al. A study on the correlation between family dynamic factors and depression in adolescents. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:1025168.

Seoane HA, et al. Sleep disruption in medicine students and its relationship with impaired academic performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2020;53:101333.

Almojali AI, et al. The prevalence and association of stress with sleep quality among medical students. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2017;7(3):169–74.

Anwer S, et al. Evaluation of Sleep habits, generalized anxiety, perceived stress, and Research Outputs among Postgraduate Research Students in Hong Kong during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:3135–49.

Houtepen LC, et al. Associations of adverse childhood experiences with educational attainment and adolescent health and the role of family and socioeconomic factors: a prospective cohort study in the UK. PLoS Med. 2020;17(3):e1003031.

Deng J, et al. The prevalence of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbance in higher education students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021;301:113863.

Pizuńska D, et al. Well-being among PhD candidates. Psychiatr Pol. 2021;55(4):901–14.

Johnson D, et al. Adult mental health outcomes of adolescent depression: a systematic review. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(8):700–16.

Smith K. Mental health: a world of depression. Nature. 2014;515(7526):181.

Marwaha S, et al. Novel and emerging treatments for major depression. Lancet. 2023;401(10371):141–53.

Urrila AS, et al. Sleep in adolescent depression: physiological perspectives. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2015;213(4):758–77.

Goldstein AN, Walker MP. The role of sleep in emotional brain function. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:679–708.

Pandi-Perumal SR, et al. Clarifying the role of sleep in depression: a narrative review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113239.

Baglioni C, et al. Sleep and mental disorders: a meta-analysis of polysomnographic research. Psychol Bull. 2016;142(9):969–90.

Schulz P, Steimer T. Neurobiology of circadian systems. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(Suppl 2):3–13.

Ebdlahad S, et al. Comparing neural correlates of REM sleep in posttraumatic stress disorder and depression: a neuroimaging study. Psychiatry Res. 2013;214(3):422–8.

Chang CH, et al. Ventromedial prefrontal cortex regulates depressive-like behavior and rapid eye movement sleep in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2014;86:125–32.

Xu H, et al. Effectiveness of inactivated COVID-19 vaccines against mild disease, pneumonia, and severe disease among persons infected with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant: real-world study in Jilin Province, China. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2023;12(1):2149935.

Bowe B, Xie Y, Al-Aly Z. Acute and postacute sequelae associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection. Nat Med. 2022;28(11):2398–405.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: We want to extend our gratitude to Shuo Wang, Yifan Jing, Zaimina Xuekelaiti, Yan Zhou, Ru Hao, Lidan Yuan, Linxuan Wang, and Ziqing Zhang from Tianjin Medical University for their assistance in collecting data. The authors thank the subjects whose participation made this study possible.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiao Liu, Daliang Sun, and Guoshuai Luo were responsible for the study design. Jiao Liu, Qingling Hao, Baozhu Li, and Ran Zhang were responsible for patient recruitment and data collection. Jiao Liu was responsible for statistical analysis. Jiao Liu, Qingling Hao, Daliang Sun, and Guoshuai Luo were involved in conceptualizing, writing, and editing the manuscript and responding to reviewers. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol for the research project had been approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Tianjin Anding Hospital (approving number: 2023-027) and had therefore been performed following the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Patients’ informed consent forms were obtained, and their anonymity was protected.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it.The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Hao, Q., Li, B. et al. Prevalence and influencing factors of sleep disorders in medical students after the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry 24, 538 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05980-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05980-0