Abstract

Background

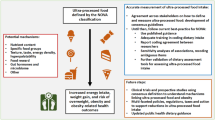

Postpartum Depression (PPD) is a major depressive disorder that mainly begins within one month after delivery. The present study aimed to determine the relationship between dietary patterns and the occurrence of high PPD symptoms in women participating in the initial phase of the Maternal and Child Health cohort study, Yazd, Iran.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was carried out in the years 2017–2019 included 1028 women after childbirth The Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) were study tools. The EPDS questionnaire was used to measure postpartum depression symptoms and a cut-off score of 13 was considered to indicate high PPD symptoms. The baseline data related to dietary intake was collected at the beginning of the study at the first visit after pregnancy diagnosis and the data related to depression, were collected in the second month after delivery. Dietary patterns were extracted by exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Frequency (percentage) and mean (SD) were used for description. Chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, independent sample t-test, and multiple logistic regression (MLR) were used for data analysis.

Results

The incidence of high PPD symptoms was 24%. Four posterior patterns were extracted including prudent pattern, sweet and dessert pattern, junk food pattern and western pattern. A high adherence to the western pattern was associated with a higher risk of high PPD symptoms than a low adherence (ORT3/T1: 2.67; p < 0.001). A high adherence to the Prudent pattern was associated with a lower risk of high PPD symptoms than a low adherence (ORT3/T1: 0.55; p = 0.001). There are not any significant association between sweet and dessert and junk food patterns and high PPD symptoms risk (p > 0.05).

Conclusion

High adherence to prudent patterns was characterized by high intake of vegetables, fruit and juice, nuts and beans, low-fat dairy products, liquid oil, olive, eggs, fish, whole grains had a protective effect against high PPD symptoms, but the effect of western pattern was characterized by high intake of red and processed meats and organs was reverse. Therefore, it is suggested that health care providers have a particular emphasis on the healthy food patterns such as the prudent pattern.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression is one of main causes of disease burden worldwide, and almost one in five people experiencing a major depressive disorder during their lifetime. Over the course of a lifetime, depression is almost twice as common in women as in men [1] and it is especially common during and in the first year after giving birth. The antepartum and postpartum periods of time may be important times to diagnosis and decrease the risk of depression [2]. The formation of the fetus and its birth cause mental health disorders including depression [3].

Pregnancy creates various hormonal, physical, emotional and psychological changes in women, so that different emotions from joy and pleasure to sadness and crying arise in the mother [4, 5]. “Baby blues” is a kind of feeling of sadness and discomfort that occurs after birth of a child which decreases in the first 2 weeks after delivery in mothers [3, 5,6,7,8,9] but postpartum depression (PPD) occurs up to one month after childbirth which has more severe and long lasting effects on mothers [10]. PPD threatens the health of the mother and her baby, and a depressed mother has the possibility of harming herself and her child, also it affects the health of the entire family, including husband and other family members [11, 12]. PPD can be the beginning of other and longer-term disorders and untreated depression can have a direct impact on a woman’s emotional life by causing despair and sadness, sleep disorder, anxiety, irritability, decreased libido. Previous studies have mentioned the long-term effect of PPD and considered it to be the cause of women’s inability to return to normal function and even defined it as a negative factor on the mother-neonatal relationship [13,14,15,16] and in some cases, it may be associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors [17, 18].

The prevalence statistics of PPD disorder among women at the global level indicate a rate of 16.6–18.8%(17.7%) percent [19] Evidence demonstrates that all countries face the challenge of PPD, but low- to middle- income countries face the greatest burden [20,21,22]. PPD prevalence in Iran was estimated at about 16 to 38% [14]. In a study using Beck depression scale for screening of PPD among 6628 women during 2–12 months after delivery in rural parts of Isfahan province in Iran, the prevalence of moderately and severely depressed women was 19.3% and 19.8%, respectively [23] also, the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis in 2022 showed that during the coronavirus pandemic, the prevalence of PPD in the world increased and was estimated at about 34% with a 95% confidence interval (0.21–0.46) [24].

Although PPD is considered as a major health problem, but all the main reasons for its creation have not been identified. Various studies have identified several risk factors such as history of depression, number of children, occupation, socio-economic status, age, education level, gender of the baby [11, 16, 25,26,27]. Other studies have introduced the nutritional factor as an influencing factor on depression [28, 29]. In these studies, nutrition has been examined partially based on food units, while considering food patterns can provide better results because the combination of different foods and their interaction can have different effects on depression. Maracy et al. 2014 in their study on the relationship between dietary patterns and PPD, showed that a dietary pattern with high amount of fruits and vegetables can reduce the risk of postpartum depression [30]. Chatzi et al. showed that following a diet containing fruits, vegetables, dairy products, olives, fish and nuts can reduce postpartum depression [31]. While, there were studies that pointed out the absence of a relationship between dietary patterns and the risk of depression [32].

According to the literature review, there were contradictory results on the relationship between dietary patterns and depression. Also, different regions of the world have their own specific dietary patterns and diseases, so to determine the role of dietary patterns in PPD, it seems necessary to conduct other studies in different regions of the world, moreover with the rapid conversion of social economy status, the diversity of food has increased, so the interactions between various foods and nutrients have become more complicated. Therefore, the present study aimed to determine the relationship between dietary patterns and the occurrence of high PPD symptoms using posteriori method in women participating in the initial phase of the Maternal and Child Health cohort study, Yazd, Iran.

Methods

Data were obtained from the Maternal and Child Health cohort study in Iran, started in the fall 2017 until the winter 2019. This study is a part of the cohort study that is being conducted on 3000 women referring for pregnancy care health centers. Women are followed up until the end of pregnancy and also evaluate the baby and the health of the mother two months after giving birth. Among the 3000 mothers included in the cohort, in our study, 1038 mothers were included for postpartum evaluation and completed the questionnaire two months after delivery. Of these mothers, 4 participants due to not completing the FFQ and 3 participants due to reporting total calories intake below 800 or above 6000 and 3 participants due to not completing the EPDS questionnaire were excluded of the study and 1028 mothers were included in this cross-sectional study. 1028 women were included in this cross-sectional study. Pregnant mothers who completed the mental status questionnaire (MSQ) two months after giving birth were included in the study [33], one of the parts of MSQ questionnaire was EPDS, which was used to assess the presence of postpartum depression symptoms. The inclusion criteria was living in Yazd province, which is located in the central part of Iran, completing the informed consent form, intending to stay in Yazd province for at least 4 years, being at least 15 years old, receiving services from health centers in Yazd province during last year, completing food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) [34]at the beginning and during of pregnancy. Exclusion criteria was the presence of mental illness or depression before pregnancy, specific illness including epilepsy and nephropathy or cancer, abnormal pregnancy. All procedures in the study involving human subjects were approved by the Research Ethics Committees at Shahid Sadoughi University of medical sciences, Yazd, Iran.

Dietary data collection

The dietary intake was assessed by a semi quantitative food frequency questionnaire, included 88 items with specific serving sizes. The FFQ contains the following seven frequency options: almost never, less than once a week, once a week, 2–3 times a week, 4–6 times a week, once a day, and more than two times a day. The participants estimated the portion size, using household measures (cups). The frequency category of each food was calculated to the daily intake. The psychometric properties of this questionnaire in Iran were investigated and confirmed by Sharifi among pregnant female in 2016. In the study of Sharifi et al., Pearson correlation coefficients between test and retest for foods was r = 0.845. The Kaiser-Meyer-Oilskin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.584, P values for the Bartlett test of sphericity were all less than 0.001 [35].

The edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS)

The postpartum depression was measured by using a questionnaire called the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) which included 10 items of 4-point Likert scale. People who score 13 or higher were considered as high PPD symptoms [21, 36,37,38]. The psychometric properties of this tool were investigated and confirmed in Iran by Mazhari and Nakhaee in 2007 [39], they considered EPDS of 12/13 as high symptoms of depression score. According to Phillips et al. study, EPDS scores of 13 or over are considered indicative of likely major depression and scores between 10 and 12 of likely minor depression [31, 40]. In the present study we decided to use the cut-off point of 13, as it has been shown to achieve high sensitivity (95%) and specificity (93%) when compared with clinical psychiatric interview [31], and this score is recommended for use when reporting on high depression symptoms in postpartum women.

Dietary patterns

In measuring the dietary patterns of mothers, according to Khaled et al.‘s 2020 study [41], the items of the FFQ questionnaire were categorized into twenty food groups (Table 1), the similarity of nutrient profiles was the basis of this classification. The food groups are: vegetables, fruit and juice, Nuts and beans, Low-fat dairy products, Liquid oil, olive, egg, fish, whole grains, tea, sweet jam and desserts, refined grain, solid oil, salty snacks, salt, red meat, processed meats and organs, high-fat dairy, Industrial drinks and Birds.

Factor analysis with the principal component factor extraction method was conducted using the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0, and varimax rotation was used to make uncorrelated factors easier to interpret. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sample adequacy and the Bartlett test of sphericity were used to assess data adequacy for factor analysis. The result of the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test was 0·67 and the Bartlett test was significant (P < 0·001), indicating that factor analysis of the data would be useful. The eigenvalue and scree plot were used to decide which factors remained. After evaluating the eigenvalues, the scree plot test and interpretability, the factors with eigenvalues ≥ 1·0 were retained.

Covariates

A general questionnaire was used to collect information. Well-trained examiners measured the anthropometric indices of participants with light clothing and without shoes. Height was measured to the nearest 0·1 cm and weight was measured to the nearest 0·1 kg. BMI was calculated by dividing weight (in kilograms) by the square of height (in meters). Waist circumference (WC) was measured to the nearest 0·1 cm at the middle point between the lowest point of the rib cage and the iliac crest. The blood pressure was measured in the sitting position after a 10 min rest period. The appearance of the first sound was used to define systolic blood pressure (SBP) and the disappearance of the sound was used to define diastolic blood pressure (DBP). The SBP and DBP were recorded twice, and the average of each measurement was used for data analysis. If the two measurements differed by more than 5 mmHg, additional readings were taken.

Education level was classified into three categories: Diploma and less, Associate’s degree and Bachelor, Master and PhD. Family income, the total monthly income of all family members, was divided into four categories. The type of delivery included types of natural delivery and delivery by caesarean section. The job status, Cigarette smoking status, History of chronic illness, gestational diabetes and hypertension during pregnancy and the use of dietary supplement during pregnancy assessed at the beginning of the study. Sleep quality was evaluated by 18 items Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [42]. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) were validated in Iranian population by Farrahi Moghaddam [43]. In a study conducted on pregnant women in Iran, the reliability of PSQI was reported 0.84 [42]. Physical activity status calculated by the Metabolic Equivalent (METs) [44,45,46]. The physical activity level was gathered by the international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) [45] and calculating metabolic equivalent of task [46]. The reliability and validity of this questionnaire had been assessed in the study by Rashidkhani et al [47].

Regarding the time of data collection, all questionnaires were filled in the first trimester of pregnancy before the 20th week of pregnancy, and in the field of EPDS, they were completed two months after delivery.

Statistical analysis

In order to study the baseline characteristics, the people were divided into two groups, high PPD symptoms group, which included the mothers with score 13 and above, and low PPD symptoms group which included the mothers with score 12 and below. Frequency (percentage) was used to describe qualitative variables and mean (SD) was used for quantitative variables. In order to check the homogeneity of the distribution of variables in two groups, chi-square tests, Fisher’s exact test and two independent samples t-test were used. The dietary patterns were extracted using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) based on food groups. The results of sample size adequacy for factor analysis through the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s sphericity test reported. In EFA, the number of latent factors was determined using eigenvalues greater than one and also using scree plot. Rotation of factors through Varimax with Kaiser Normalization method was performed. The naming of the patterns was done based on the food items included in that factor.

To determine the relationship between the incidence of high PPD symptoms and food patterns, multiple logistic regression model was used. In this model, the effect of baseline characteristics such as subjective sleep quality, religion, job status, energy, waist circumference and BMI in the first trimester were controlled. Adjusted risk ratio (OR adj) and 95% confidence interval were calculated. All analyzes were performed in SPSS software version 24, by considering a significance level of 5%.

Results

A total of 1028 women participated in the study included 247 high PPD symptoms individuals and 781 low PPD symptoms individuals. Based on depression scores, the overall presence of high PPD symptoms prevalence, which indicated the mothers whose depressive symptom scores were above 13, was 24%. The mean (SD) of age was 28.89(5.32) years. The description of baseline characteristics according to two groups, high PPD symptoms group which included the mothers with score 13 and above and low PPD symptoms group which included the mothers with score 12 and below, is presented in Table 2.

According to Table 2, in terms of sleep quality, the majority of people reported a good level (58.5% in low PPD symptoms PPD vs.50.2 in high PPD symptoms). Regarding the level of education, the highest percentage was related to the diploma level and below, so that it was 49.23% in the high PPD symptoms group vs. 49.31% in the low PPD symptoms group. In terms of occupation, most people in the two groups were housewives (76.14 in the high PPD symptoms group vs. 74.05 in the low PPD symptoms group). Comparing the two groups based on income, smoking, history of chronic disease, gestational diabetes, dietary supplement use during pregnancy, types of Childbirth, and the gender of the baby did not show any significant difference between the two groups (p > 0.05). In terms of energy intake, in the low PPD symptoms vs. high PPD symptoms groups, it was equal to 2546.15 kcal per day and 2339.28 kcal per day, respectively (p = 0.001). In terms of systolic and diastolic blood pressure, waist circumference, HDL, TG, FBS, age and met equivalent both groups were homogeneous (p > 0.05).

The results of EFA in determining the later food patterns extracted four patterns. The factor loading matrix is shown in Table 3. These four patterns explained 34% of the variance, namely ‘prudent pattern’, ‘sweet and dessert pattern’, ‘junk food pattern’ and ‘western pattern’. After evaluating the eigenvalues, the scree plot test and interpretability, factors with eigenvalues ≥ 1·0 were retained, and individual food items with absolute factor loadings ≥ 0·25 were considered to contribute significantly to the pattern [48]. the detailed foods of the four dietary patterns mentioned above are: prudent pattern (high intake of vegetables, fruit and juice, nuts and beans, low-fat dairy products, liquid oil, olive, eggs, fish, whole grains), sweet and dessert pattern (high intake of tea, sweet jam and desserts and refined grain), junk food pattern (high intake of salt, salty snacks and solid oil) and western pattern (high intake of red meat and processed meats and organs). The overall Cronbach’s Alpha was0.74 and Cronbach’s alpha of each food group was as follows: vegetables 0.85, fruit and juice0.86, nuts and beans 0.67, low-fat dairy Products0.85, liquid oil 0.65, olive 0.75, eggs 0.72, fish 0.71, whole grains 0.83, tea 0,72, sweet jam and desserts 0.64, refined grain 0.61, solid oil 0.82, salty snacks 0.8, salt 0.65, red meat 0.84, processed meats and organs 0.73, high-fat dairy 0.74, industrial drinks 0.7, chickens 0.68.

For investigating the relationship between high PPD symptoms incidence and dietary patterns, four dietary patterns which extracted by EFA were enter into logistic regression model. Also, multiple logistic regression results were adjusted for effects of the other variables (Table 4).

The results of multiple logistic regression showed in the prudent pattern, which included healthy foods and fruits, a high adherence to the healthy foods and fruits was associated with a lower risk of high PPD symptoms than a low adherence, so that in the model #4 with controlling all confounding variables, the risk of high PPD symptoms in the second tertile was 47% less than the first and the third tertile was 45% less than the first tertile (OR2vs1 = 0.53, OR3vs1 = 0.55 P < 0.05), there were similar results in other models.

There was no significant relationship between adhering to the Sweet and Dessert Pattern and Junk Food Pattern with incidence of high PPD symptoms (p > 0.05). In the Western pattern which included high intake of red and processed meat, a high adherence to this pattern was associated with a higher risk of high PPD symptoms than a low adherence, so that in the model #4 with controlling all confounding variables, mothers who were in the third tertile had 2.67 times more risk to getting high PPD symptoms than mothers in the first tertile (OR = 2.67, P < 0.001) and mothers who were in the second tertile had a 1.79 times higher risk of catching high PPD symptoms PPD than mothers in the first tertile (OR = 1.79, P = 0.002). There were similar results in other models.

Discussion

PPD is a major depressive disorder that mainly begins within one month after delivery [49]. This disease as a fundamental issue in public health not only affects the life of the mother, but also has an effect on the growth and development of the child, cognitive, social and behavioral opinion [10]. It can even lead to mother’s suicide and harm to the child. So, the present study aimed to determine the relationship between dietary patterns and the occurrence of high PPD symptoms in women participating in the first phase of Iranian Maternal and Child Health cohort study, Yazd, Iran.

Our results showed the incidence of high PPD symptoms, which indicated the mothers whose depressive symptom scores were above 13, was acquired at 24%. In similar studies in Iran [50,51,52,53], the prevalence of PPD was estimated 15–41%. In the present study, Examining the homogeneity of the distribution of quantitative and qualitative variables in high PPD symptoms vs. low PPD symptoms groups showed that only the energy intake variable was different in the two groups, so that energy intake was significantly higher in low PPD symptoms women. In line with the present study, in the study of Most et al., 2020, it was emphasized that women with PPD consumed less energy and have weight lost compared to the period of pregnancy [15]. According to research, about 50–75% of depressed patients also have anorexia. Anorexia aggravates physical and mental problems over time, and if treatment is not done, it causes very dangerous consequences for patients. Therefore, it seems logical that women with PPD have less energy consumption and lose weight.

Sleep quality is another concern of women after childbirth. Sleep disturbance can occur in the form of deprivation, which refers to a lack of sleep, or fragmentation, which refers to numerous awakenings after an individual falls asleep [54]. Sleep is a basic physiological need and a complex physiological process that restores physical agility and energy. The main cause of sleep disturbance after delivery is infant signaling during the night [55]. A sleep quality study at postpartum of women suggested that poor sleep quality is linked with increased depression and anxiety symptoms in women at six months after delivery. Moreover, the study was used both the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) to investigate the relationship between changes in self-reported sleep patterns and depressive symptoms, revealed that those who are at a high risk of PPD are also at a higher risk of developing depressive symptoms later in their postpartum period if sleep issues persist or improve very minimally over time [56]. While these studies produced insightful results regarding the relationship between sleep disturbance and the risk of developing PPD, there was heterogeneity in terms of the sample characteristics and the timepoints at which PPD symptoms were studied. In this study, although poor sleep quality amount in high PPD symptoms group were approximately 8% more than low PPD symptoms group (p = 0.022) that shown in Table 2, but after adjustment of sleep quality, no significant difference between dietary patterns and high PPD symptoms was observed (Table 4).

The results of EFA confirmed the extraction of four patterns were named based on the food groups included in them. For instance, prudent pattern included high intake of healthy foods, fruits and vegetables. Results of multiple logistic regression showed, compare to low adherence, a high adherence to the healthy foods and fruits was associated with a lower risk of high PPD symptoms. In line with our study, a study conducted by Maracy et al. in 2014 in Iran, showed a significant relationship between the incidence of PPD and the dietary pattern of fruits and vegetables, so that women who consumed more fruits and vegetables during pregnancy had a lower odds of getting PPD [30]. They also emphasized that this pattern has a protective effect against PPD that it was consistent with our study. Contrary to the results of our study, a study in Japan showed that there was no significant relationship between dietary pattern and PPD [48]. A cohort study conducted by Baskin et al. in 2017 showed that there was no relationship between dietary patterns and incidence of PPD in pregnant women [57]. In general, considering the different conditions of the studies and attention to the existing contradictions, it seems that more studies are needed to determine the role of dietary patterns in the incidence of depression.

Previous studies concentrating on single food groups have shown that higher intakes of fish [58], fruit and vegetables [59] and fiber intake [60] are associated with lower depressive symptoms. However, analyzing food groups individually has limitations because the role of these individual components is examined without considering the complication of a dietary pattern [61]. An examination of food groups showed that higher vegetable intake was related to lower depression and this association was as expected. Thus, higher consumption of non-refined grains, vegetables, fruit, potatoes, fish and olive oil were inversely related to depression or lower odds of a current diagnosis, while higher consumption of poultry and high fat dairy products was positively associated with higher depressive symptoms [62]. Contrary to a meta-analysis indicated that high-fish consumption reduced the risk of depressive symptoms [58], Gibson, et al. found no associations between fish and depressive symptoms that lack of findings could be due to the generally low levels of fish consumption in that society [62].

Another posteriori pattern which extracted by EFA in this study was the sweet and dessert pattern, it was related to the consumption of sweets, desserts and refined grains. The findings of our study showed that there was no significant relationship between adhering to the Sweet and Dessert Pattern and PPD incidence. Many studies pointed out a significant effect of the sweet and dessert pattern on depression so that, a high adherence to this pattern was associated with a higher odds ratio of PPD than a low adherence [57, 63, 64]. According to the contradictory results of previous studies, it seems that longitudinal studies should be planned in this field.

The third posterior dietary pattern extracted by EFA was junk food pattern. This pattern focused on salty snacks and solid oils. The results of our study showed that there was no significant relationship between adhering to this pattern and incidence of PPD symptoms. Some studies showed the negative effect of unhealthy diet such as salty snacks on depression so that a high adherence to this pattern was associated with a higher odds ratio of PPD than a low adherence [65,66,67]. In the present study, although the adherence to this pattern had not significant relationship with high PPD symptoms occurrence, a high adherence to this pattern was associated with a higher risk of high PPD symptoms than a low adherence. The non-significance and inconsistency of our findings with previous studies can be due to the study design and different sample size. On the other hand, the present study was the first phase of a cohort study, maybe different results will be obtained in the next follow-ups. Results from previous mental health focused papers showed that vegetables, fruit, high fiber, fish, low fat dairy were associated with depression inversely, and sugar-sweetened beverages, fast food, snacks and sweets were positively associated with depressive symptoms. [68,69,70,71].

The fourth extracted posterior Dietary pattern was western pattern. This pattern focused on processed and red meat and organs consumption. Results of our study showed that a high adherence to the processed and red meat was associated with a higher risk of high PPD symptoms than a low adherence. In line with the present study, Nucci et al., in a systematic review and meta-analysis with a review of 18 studies and a population of 160,000 people, concluded that consumption of red meat and processed meat increases the chance of depression [72]. Therefore, according to the importance of the mentioned review, and the findings of the present study, paying attention to the western diet and trying to reduce adherence to it in pregnant women can help to a large extent in preventing the development of high PPD symptoms in women.

The malefic effect of Western pattern on inflammation and coronary heart disease [73, 74] can play a role in the pathogenesis of depression [75, 76]. However, further studies are needed to research the association between western pattern, the inflammation process and depression.

There are several plausible mechanisms underlying the association between the dietary patterns and depression are complicated and reasons for bilateral relations can be provided. First, changes in appetite and weight, poor motivation, and low energy levels are symptoms usually seen in depressed people [77], for this reason, changes in energy intake and reduction in personal health behaviors occur [78]. Because unhealthy foods usually are prepared faster and easier than healthy foods, it could be expected that the diet quality may decrease. Second, deficiencies in certain vitamins [79], minerals [80], and essential fatty acids [81] may affect depression by directly influencing biological pathways related to the pathophysiology of depression. Vegetables are an important source of minerals, fiber, alpha-linolenic acid, vitamins, and other anti-oxidants. The high level of antioxidants in fruits and vegetables could counteract free radicals and oxidative stress, which has been shown to be increased in depressed persons [82,83,84]. Also, a high content of folate in some leafy green vegetables and legumes has a positive role in improvement of depression diseases [85]. It has been suggested that low levels of folate might increase the risk of depression and result in reduced availability of S-adenosylmethionine, which can result in disruption of formation of myelin, neurotransmitters and membrane phospholipids [86]. Low levels of folic acid and zinc, whose found in vegetables and non-refined grain products, have been associated with depression [87, 88]. The other studies suggested the protective effect of long-chain ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in depression. These are a major component of neuron membranes that have anti-inflammatory properties [76, 89,90,91]. Third, diet may indirectly affect depression through negatively affecting the gut microbiome and causing low level inflammation, which leads to the risk of depression. Finally, we should consider that the association between dietary pattern and depression may have been confounded by social economic status and income [92, 93]. Many of the food groups associated with lower depression are typically more expensive and more often consumed by those of higher income, SES and education, and although we adjusted for education level, there may have been residual confounding by social economic status [94]. Some limitations of our study should be noted. First, the local and cross-sectional nature of the study, which might limit the capability to communalize the results to other areas. Second, is the memory bias that may occur when a self-reported and long-term dietary assessment method such as the semi quantitative FFQ is applied. Third, the instrument of PPD in our study was EPDS questionnaire which evaluated the symptoms of depression and it is not a diagnostic tool, in this study PPD was not diagnosed by psychiatrists and high depressive symptoms at 2 months postpartum were considered high PPD symptoms; however, definitions may vary. Forth, in this study, from an initial sample of 3000 subjects only 1028 women concluded the research.

One of the strengths of this study is the large sample size and the use of cohort data. Another strength of the study is the adjustment of some confounder variables like sleep quality, which can make an impact on the results.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that high adhering to the Western Pattern increased the risk of high PPD symptoms. On the other hand, Sweet and desert, junk food pattern had no significant relationship with high PPD symptoms. Therefore, it is suggested that the women health care providers have a particular emphasis on the adherence to healthy food patterns such as the prudent patterns.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PPD:

-

Postpartum Depression

- FFQ:

-

Food Frequency Questionnaire

- EPDS:

-

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

- EFA:

-

Exploratory factor analysis

- MLR:

-

Multiple logistic regression

- MSQ:

-

Mental status questionnaire

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- PSQI:

-

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- METs:

-

Metabolic Equivalent

- HDL:

-

High density lipoprotein

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- FBS:

-

Fasting blood sugar

References

Kessler RC, Bromet EJ. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:119–38.

Van Niel MS, Payne JL. Perinatal depression: a review. Cleve Clin J Med. 2020;87(5):273–7.

Weinstock M. The potential influence of maternal stress hormones on development and mental health of the offspring. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19(4):296–308.

Yeo JH, Chun N. [Influence of childbirth experience and postpartum depression on quality of life in women after birth]. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2013;43(1):11–9.

Mughal S, Azhar Y, Siddiqui W. Postpartum Depression. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2022. StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2022.

Zauderer C. Postpartum depression: how childbirth educators can help break the silence. J Perinat Educ. 2009;18(2):23–31.

Berglund J. Treating Postpartum Depression: beyond the Baby Blues. IEEE pulse. 2020;11(1):17–20.

Chechko N, Stickel S, Votinov M. Neural responses to monetary incentives in postpartum women affected by baby blues. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2023;148:105991.

Mones SY, Lada CO, Jutomo L, Trisno I, Roga AU. The influence of individual characteristics, Internal and External factors of Postpartum mothers with Baby Blues Syndrome in Rural and Urban Areas in Kupang City. 2023.

Bass PF III, Bauer N. Parental postpartum depression: more than “baby blues”. Contemp PEDS J. 2018;35(9).

Gebregziabher NK, Netsereab TB, Fessaha YG, Alaza FA, Ghebrehiwet NK, Sium AH. Prevalence and associated factors of postpartum depression among postpartum mothers in central region, Eritrea: a health facility based survey. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–10.

Ahmadpour P, Faroughi F, Mirghafourvand M. The relationship of childbirth experience with postpartum depression and anxiety: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol. 2023;11(1):1–9.

DelRosario GA, Chang AC, Lee ED. Postpartum depression: symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment approaches. JAAPA: official journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2013;26(2):50–4.

Koutra K, Vassilaki M, Georgiou V, Koutis A, Bitsios P, Kogevinas M, et al. Pregnancy, perinatal and postpartum complications as determinants of postpartum depression: the Rhea mother–child cohort in Crete. Greece Epidemiol psychiatric Sci. 2018;27(3):244–55.

Most J, Altazan AD, St. Amant M, Beyl RA, Ravussin E, Redman LM. Increased energy intake after pregnancy determines postpartum weight retention in women with obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metabolism. 2020;105(4):e1601–e11.

Yadav T, Shams R, Khan AF, Azam H, Anwar M, Anwar T et al. Postpartum Depression: Prevalence and Associated Risk factors among women in Sindh, Pakistan. Cureus. 2020;12(12).

Maghami M, Shariatpanahi SP, Habibi D, Heidari-Beni M, Badihian N, Hosseini M, et al. Sleep disorders during pregnancy and postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2021;81(6):469–78.

Shigemi D, Ishimaru M, Matsui H, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H. Suicide attempts among pregnant and postpartum women in Japan: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(3):20382.

Hahn-Holbrook J, Cornwell-Hinrichs T, Anaya I. Economic and health predictors of national postpartum depression prevalence: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of 291 studies from 56 countries. Front Psychiatry. 2018;8:248.

Upadhyay RP, Chowdhury R, Salehi A, Sarkar K, Singh SK, Sinha B, et al. Postpartum depression in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(10):706.

Roumieh M, Bashour H, Kharouf M, Chaikha S. Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depression among women seen at Primary Health Care Centres in Damascus. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):1–5.

Almond P. Postnatal depression: a global public health perspective. Perspect public health. 2009;129(5):221–7.

Kheirabadi G-R, Maracy M-R, Barekatain M, Casey PR. Risk factors of postpartum depression in rural areas of Isfahan Province, Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2009;12(5):461–7.

Chen Q, Li W, Xiong J, Zheng X. Prevalence and risk factors associated with postpartum depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: a literature review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(4):2219.

Alshikh Ahmad H, Alkhatib A, Luo J. Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression in the Middle East: a systematic review and meta–analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):1–12.

Wang D, Li Y-L, Qiu D, Xiao S-Y. Factors influencing paternal postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;293:51–63.

Zhao X-h, Zhang Z-h. Risk factors for postpartum depression: an evidence-based systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Asian J psychiatry. 2020;53:102353.

Judge MP, Beck CT. Postpartum depression and the role of nutritional factors. Handbook of nutrition and pregnancy: Springer; 2018. p. 357 – 83.

Shi D, Wang G-h, Feng W. Nutritional assessments in pregnancy and the risk of postpartum depression in chinese women: a case-control study. Medicine. 2020;99(33).

Maracy M, Iranpour S, Esmaillzadeh A, Kheirabadi G. Dietary patterns during pregnancy and the risk of postpartum depression. Iran J Epidemiol. 2014;10(1):45–55.

Chatzi L, Melaki V, Sarri K, Apostolaki I, Roumeliotaki T, Georgiou V, et al. Dietary patterns during pregnancy and the risk of postpartum depression: the mother–child ‘Rhea’cohort in Crete, Greece. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(9):1663–70.

Okubo H, Inagaki H, Gondo Y, Kamide K, Ikebe K, Masui Y, et al. Association between dietary patterns and cognitive function among 70-year-old japanese elderly: a cross-sectional analysis of the SONIC study. Nutr J. 2017;16(1):1–12.

Robertson D, Rockwood K, Stolee P. A short mental status questionnaire. Can J Aging/La Revue canadienne du vieillissement. 1982;1(1–2):16–20.

Ayoubi SS, Yaghoubi Z, Pahlavani N, Philippou E, MalekAhmadi M, Esmaily H et al. Developed and validated food frequency questionnaires in Iran: a systematic literature review. J Res Med Sciences: Official J Isfahan Univ Med Sci. 2021;26.

Sharifi SF, Javadi M, Barikani A. Reliability and validity of short food frequency questionnaire among pregnant females. Biotechnol health Sci. 2016;3(2).

Hung KJ, Tomlinson M, le Roux IM, Dewing S, Chopra M, Tsai AC. Community-based prenatal screening for postpartum depression in a south african township. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2014;126(1):74–7.

Poeira AF, Zangão MO. Improving Sleep Quality to prevent Perinatal Depression: the obstetric nurse intervention. Int J Translational Med. 2023;3(1):42–50.

Toh MP, Yang CY, Lim PC, Loh HLJ, Bergonzelli G, Lavalle L, et al. A probiotic intervention with Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 on Perinatal Mood Outcomes (PROMOTE study): protocol for a decentralized Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protocols. 2023;12(1):e41751.

Mazhari S, Nakhaee N. Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale in an iranian sample. Arch Women Ment Health. 2007;10(6):293–7.

Phillips J, Charles M, Sharpe L, Matthey S. Validation of the subscales of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale in a sample of women with unsettled infants. J Affect Disord. 2009;118(1–3):101–12.

Khaled K, Hundley V, Almilaji O, Koeppen M, Tsofliou F. A priori and a posteriori dietary patterns in women of childbearing age in the UK. Nutrients. 2020;12(10):2921.

Effati-Daryani F, Mohammad-Alizadeh‐Charandabi S, Mohammadi A, Zarei S, Mirghafourvand M. Evaluation of sleep quality and its socio-demographic predictors in three trimesters of pregnancy among women referring to health centers in Tabriz, Iran: a cross-sectional study. Evid Based Care. 2019;9(1):69–76.

Farrahi Moghaddam J, Nakhaee N, Sheibani V, Garrusi B, Amirkafi A. Reliability and validity of the Persian version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI-P). Sleep & breathing = Schlaf & Atmung. 2012;16(1):79–82.

Jetté M, Sidney K, Blümchen G. Metabolic equivalents (METS) in exercise testing, exercise prescription, and evaluation of functional capacity. Clin Cardiol. 1990;13(8):555–65.

Collaborators GO. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):13–27.

Reynolds A, Mann J, Cummings J, Winter N, Mete E, Te Morenga L. Carbohydrate quality and human health: a series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The Lancet. 2019;393(10170):434–45.

Rashidkhani B, Hajizadeh Armaki B, HoushiarRad A, Moasheri M. Dietary patterns and risk of squamous-cell carcinoma of esophagus in Kurdistan Province, Iran. Iran J Nutr Sci Food Technol. 2008;3(3):11–21.

Okubo H, Miyake Y, Sasaki S, Tanaka K, Murakami K, Hirota Y. Dietary patterns during pregnancy and the risk of postpartum depression in Japan: the Osaka maternal and Child Health Study. Br J Nutr. 2011;105(8):1251–7.

De Crescenzo F, Perelli F, Armando M, Vicari S. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for post-partum depression (PPD): a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. J Affect Disord. 2014;152:39–44.

Afshari P, Tadayon M, Abedi P, Yazdizadeh S. Prevalence and related factors of postpartum depression among reproductive aged women in Ahvaz. Iran Health care women Int. 2020;41(3):255–65.

Jahromi MK, Mohseni F, Manesh EP, Pouryousef S, Poorgholami F. A study of social support among non-depressed and depressed mothers after childbirth in Jahrom, Iran. Bangladesh J Med Sci. 2019;18(4):736–40.

Kamkar M-Z, Zargarani F, Behnampour N. Postpartum Depression in Women with Normal Delivery and Cesarean Section Referring to Sayad Shirazi Hospital of Gorgan, Iran. 2019.

Mahdavy M, Kheirabadi G. The prevalence of Postpartum Depression and its related factors among women in Natanz City in 2018 (Iran). Qom Univ Med Sci J. 2020;14(2):78–85.

Lee KA, Gay CL. Sleep in late pregnancy predicts length of labor and type of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;1916:2041–6.

Nishihara K, Horiuchi S, Eto H, Uchida S. Mothers’ wakefulness at night in the post-partum period is related to their infants’ circadian sleep–wake rhythm. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;54(3):305–6.

Lewis BA, Gjerdingen D, Schuver K, Avery M, Marcus BH. The effect of sleep pattern changes on postpartum depressive symptoms. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):1–7.

Baskin R, Hill B, Jacka FN, O’Neil A, Skouteris H. Antenatal dietary patterns and depressive symptoms during pregnancy and early post-partum. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13(1):e12218.

Li F, Liu X, Zhang D. Fish consumption and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(3):299–304.

Liu X, Yan Y, Li F, Zhang D. Fruit and vegetable consumption and the risk of depression: a meta-analysis. Nutrition. 2016;32(3):296–302.

Miki T, Eguchi M, Kurotani K, Kochi T, Kuwahara K, Ito R, et al. Dietary fiber intake and depressive symptoms in japanese employees: the Furukawa Nutrition and Health Study. Nutrition. 2016;32(5):584–9.

McNaughton SA. Dietary patterns and diet quality: approaches to assessing complex exposures in nutrition. Australasian Epidemiologist. 2010;17(1):35–7.

Gibson-Smith D, Bot M, Brouwer IA, Visser M, Giltay EJ, Penninx BW. Association of food groups with depression and anxiety disorders. Eur J Nutr. 2020;59:767–78.

Akbaraly TN, Brunner EJ, Ferrie JE, Marmot MG, Kivimaki M, Singh-Manoux A. Dietary pattern and depressive symptoms in middle age. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(5):408–13.

Le Port A, Gueguen A, Kesse-Guyot E, Melchior M, Lemogne C, Nabi H, et al. Association between dietary patterns and depressive symptoms over time: a 10-year follow-up study of the GAZEL cohort. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e51593.

Khalid S, Williams CM, Reynolds SA. Is there an association between diet and depression in children and adolescents? A systematic review. Br J Nutr. 2016;116(12):2097–108.

Paans NP, Gibson-Smith D, Bot M, van Strien T, Brouwer IA, Visser M, et al. Depression and eating styles are independently associated with dietary intake. Appetite. 2019;134:103–10.

Rahe C, Baune BT, Unrath M, Arolt V, Wellmann J, Wersching H, et al. Associations between depression subtypes, depression severity and diet quality: cross-sectional findings from the BiDirect Study. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15(1):1–9.

Akbaraly TN, Sabia S, Shipley MJ, Batty GD, Kivimaki M. Adherence to healthy dietary guidelines and future depressive symptoms: evidence for sex differentials in the Whitehall II study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(2):419–27.

El Ansari W, Adetunji H, Oskrochi R. Food and mental health: relationship between food and perceived stress and depressive symptoms among university students in the United Kingdom. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2014;22(2):90–7.

Mikolajczyk R, El Ansari W, Maxwell,AE. Food Consumption frequency and perceived stress and depressive symptoms among students in three european countries. Nutr J. 2009;8:31.

Rius-Ottenheim N, Kromhout D, Sijtsma FP, Geleijnse JM, Giltay EJ. Dietary patterns and mental health after myocardial infarction. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(10):e0186368.

Nucci D, Fatigoni C, Amerio A, Odone A, Gianfredi V. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6686.

Hu FB. Dietary pattern analysis: a new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13(1):3–9.

Lopez-Garcia E, Schulze MB, Fung TT, Meigs JB, Rifai N, Manson JE, et al. Major dietary patterns are related to plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(4):1029–35.

Kamphuis MH. Depression and cardiovascular disease: the role of diet, lifestyle and health. Utrecht University; 2006.

Tiemeier H, Hofman A, van Tuijl HR, Kiliaan AJ, Meijer J, Breteler MM. Inflammatory proteins and depression in the elderly. Epidemiology. 2003:103–7.

American Psychiatric Association, Association D. AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. American psychiatric association Washington, DC; 2013.

Allgöwer A, Wardle J, Steptoe A. Depressive symptoms, social support, and personal health behaviors in young men and women. Health Psychol. 2001;20(3):223.

Bender A, Hagan KE, Kingston N. The association of folate and depression: a meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;95:9–18.

Wang J, Um P, Dickerman BA, Liu J. Zinc, magnesium, selenium and depression: a review of the evidence, potential mechanisms and implications. Nutrients. 2018;10(5):584.

Thesing CS, Bot M, Milaneschi Y, Giltay EJ, Penninx BW. Omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid levels in depressive and anxiety disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;87:53–62.

Black CN, Bot M, Scheffer PG, Cuijpers P, Penninx BW. Is depression associated with increased oxidative stress? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:164–75.

Haytowitz D, Bhagwat S, Prior R, Wu X, Gebhardt S, Holden J. Oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) of selected foods-2007. Nutrient Data Laboratory ARS USDA; 2007.

Sarandol A, Sarandol E, Eker SS, Erdinc S, Vatansever E, Kirli S. Major depressive disorder is accompanied with oxidative stress: short-term antidepressant treatment does not alter oxidative–antioxidative systems. Hum Psychopharmacology: Clin Experimental. 2007;22(2):67–73.

Henderson L, Gregory J, Swan G. The National Diet and Nutrition Survey: adults aged 19 to 64 years. Vitamin and mineral intake and urinary analytes. 2003;3:1–8.

Selhub J, Bagley LC, Miller J, Rosenberg IH. B vitamins, homocysteine, and neurocognitive function in the elderly. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(2):614S–20S.

Gilbody S, Lightfoot T, Sheldon T. Is low folate a risk factor for depression? A meta-analysis and exploration of heterogeneity. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(7):631–7.

Li Z, Li B, Song X, Zhang D. Dietary zinc and iron intake and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:41–7.

Astorg P, Arnault N, Czernichow S, Noisette N, Galan P, Hercberg S. Dietary intakes and food sources of n – 6 and n – 3 PUFA in french adult men and women. Lipids. 2004;39(6):527–35.

Hibbeln JR. Fish consumption and major depression. Lancet. 1998;351(9110):1213.

Sanchez-Villegas A, Henríquez P, Figueiras A, Ortuño F, Lahortiga F, Martínez-González MA. Long chain omega-3 fatty acids intake, fish consumption and mental disorders in the SUN cohort study. Eur J Nutr. 2007;46(6):337–46.

Joinson C, Kounali D, Lewis G. Family socioeconomic position in early life and onset of depressive symptoms and depression: a prospective cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52:95–103.

Weich S, Lewis G. Poverty, unemployment, and common mental disorders: population based cohort study. BMJ. 1998;317(7151):115–9.

Appleton K, Woodside J, Yarnell J, Arveiler D, Haas B, Amouyel P, et al. Depressed mood and dietary fish intake: direct relationship or indirect relationship as a result of diet and lifestyle? J Affect Disord. 2007;104(1–3):217–23.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families who participated in this study and we would like to acknowledge everyone who helped us in this project.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SD-B, HM-k and MH Conceived and designed the analysis, SD-B collected the data, SD-B, HM-k, MH and FM contributes data or analysis tools, SD-B, MH and FM performed the analysis and wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was part of PhD thesis in Nutrition which was approved by the ethical committee of Shahid Sadoughi University of medical sciences supported by, Shahid Sadoughi University of medical sciences, Iran with ethical code IR.SSU.SPH.REC.1399.178. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants, materials and data were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee following the declaration of Helsinki. Signed informed consent was obtained from each participant. Confidentiality has been maintained throughout the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Dehghan-Banadaki, S., Hosseinzadeh, M., Madadizadeh, F. et al. Empirically derived dietary patterns and postpartum depression symptoms in a large sample of Iranian women. BMC Psychiatry 23, 422 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04910-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04910-w