Abstract

Background

Previous studies have investigated the relationships between psychache or meaning in life and suicidal ideation based on sum score of corresponding scale. However, this practice has hampered the fine-grained understanding of their relationships. This network analysis study aimed to conduct a dimension-level analysis of these constructs and the relationships among them in a joint framework, and identify potential intervention targets to address suicidal ideation.

Methods

Suicidal ideation, psychache, and meaning in life were measured using self-rating scales among 738 adults. A network of suicidal ideation, psychache, and meaning in life was constructed to investigate the connections between dimensions and calculate the expected influence and bridge expected influence of each node.

Results

“Psychache” was positively linked to “sleep” and “despair”, while “presence of meaning in life” had negative associations with “psychache”, “despair”, and “pessimism”. The most important central nodes were “sleep” and “despair”, and the critical bridge nodes were “presence of meaning in life” and “psychache”.

Conclusion

These preliminary findings uncover the pathological pathways underlying the relationships between psychache, meaning in life, and suicidal ideation. The central nodes and bridge nodes identified may be potential targets for effectively preventing and intervening against the development and maintenance of suicidal ideation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Suicidal ideation is defined as thoughts ranging from a vague idea of committing suicide to a specific suicide plan [1]. Some researchers have claimed that suicidal ideation is an important phase in the process of suicide, usually preceding suicide attempts and completed suicide [2]. Suicidal ideation is reported to be closely correlated with subsequent suicide attempts and completed suicide [3, 4]. An 18-month follow-up survey has shown that persistent suicidal ideation is positively associated with risk of completing suicide [5]. In addition, results of a nationwide study conducted in Finland [6], showed that 22% of those who had committed suicide had expressed suicidal ideation within 28 days before death during their last visit with a health care professional. Furthermore, a meta-analysis has also revealed that those who had reported or expressed suicidal ideation had a greater risk for completed suicide compared with those who had not, including both psychiatric and non-psychiatric populations [7]. Therefore, many investigators believe that suicidal ideation is among the most important risk factors for completed suicide and increased suicide mortality [7,8,9,10,11].

Given that suicide is a leading cause of death worldwide [12, 13], coupled with suicidal ideation being a major precursor to completed suicide, substantial efforts should be undertaken to investigate primary contributors to the development and maintenance of suicidal ideation. In other words, it is imperative to identify the pathogenesis relevant to suicidal ideation (e.g., pathological pathways, risk factors, and protective factors) to increase the effectiveness of suicide prevention and intervention.

Several psychological variables have been linked to suicidal ideation, and psychache is a critical psychological variable that contributes to suicidal ideation. According to Shneidman’s theory of suicide [14], psychache is defined as hurt, anguish, soreness, aching, and psychological pain in the mind; Shneidman proposed that when an individual experiencing psychache deems the pain unbearable, suicidal ideation to escape from it through suicide occurs. Support for psychache as the cause of suicidal ideation is strong, regardless of whether it occurs in the context of a mood disorder or in the absence of a mental disorder [15]. Previous studies have shown that psychache is closely related to, and is a prominent predictor of suicidal ideation [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Furthermore, a recent longitudinal study has revealed that psychache and suicidal ideation are reciprocally inter-related over time [24]. Altogether, psychache is a core psychological construct for understanding suicidal ideation and suicide, and studies on the relationship between them may help develop effective interventions for suicidal ideation.

Meaning in life has also been shown to be an important protective factor against suicidal ideation [25,26,27]. Meaning in life is defined as the sense made of, and significance felt regarding, the nature of one’s being and existence and is regarded as a cornerstone of well-being [28, 29]. Meaning in life is also positively related to mental health and inversely associated with negative emotions [25]. For instance, a previous study has found that participants with low meaning in life had higher levels of suicidal ideation than those with high meaning in life [25]. Meaning in life also decreases the risk of non-suicidal self-injury, suicidal thoughts and behaviors [30]. Overall, meaning in life has a close relationship with suicidal ideation, and the evidence indicates that it plays a major protective role against it. Furthermore, a close relationship between loss of meaning in life and intense psychache has also been shown in some studies [31], and greater meaning in life is inversely related to psychache [32].

Previous studies have used sum scores of various scales to examine the relationship between suicidal ideation and psychache [16, 17, 20], and relationships between suicidal ideation and meaning in life [25,26,27]. However, this approach may ignore the fine-grained relationships between the dimensions of these psychological constructs and obscure the degree of significance of different dimensions [33, 34]. For example, meaning in life is a multi-dimensional construct. Some investigators hold that it contains two dimensions: the presence of meaning in life and a search for meaning in life [26, 28, 35]. Similarly, suicidal ideation and psychache are also multidimensional constructs. To date, research based on a holistic perspective has hampered progress in this area such as identifying pathological pathways between psychopathological constructs which might suggest appropriate targets for effective therapies [36]. However, performing analysis of individual dimensions offers a promising way forward. Furthermore, previous studies of suicidal ideation, meaning in life, and psychache have rarely been investigated in a joint framework, although they are closely related, and is an additional shortcoming of previous research. To better understand the pathological pathways between the three constructs, especially between psychache and suicidal ideation, and between meaning in life and suicidal ideation, and to identify potential factors for effective and targeted interventions for suicidal ideation, studies that examine the relationships among the three constructs at a fine-grained level are needed.

Network model (i.e., network analysis) is an emerging and promising data-driven approach to psychopathology, and is able to reveal relationships between dimensions [37, 38]. Network analysis visualizes psychopathological constructs as a network consisting of nodes (dimensions or factors) and node-to-node edges (correlations between individual dimensions/factors) [39, 40]. The mental disorder network may include different associated constructs (also known as communities) and their corresponding dimensions. Network theory asserts that active interaction and mutual reinforcement of dimension nodes cause the emergence of the psychopathological construct network, rather than passively regarding individual dimensions as reflections of a latent psychopathological variable [37, 38, 41].

Utilizing network analysis to investigate psychopathological constructs has some advantages and scientific implications. The approach permits analysis of individual dimensions of constructs at a fine-grained level, overcoming the shortcomings of previous studies that evaluate relations between constructs in the single-ensemble form. It involves evaluating the importance of edges that may uncover pathways among psychopathological constructs. Moreover, network analysis can provide a predictability index for each node to assess the controllability of the node in the whole network [42]. It also provides centrality indices to identify important central nodes that activate all other nodes and exert great influence on the overall network [38, 43, 44]. In addition, it is also able to assess bridge centrality indices to determine dominant bridge nodes that are critical to maintain the co-occurrence of psychopathological constructs and facilitate the impact of one construct on others [40, 45,46,47]. However, to our knowledge, no study has investigated the relationships among suicidal ideation, psychache, and meaning in life via network analysis, not to mention using a joint framework.

To address this research gap, we constructed a network structure of suicidal ideation, psychache, and meaning in life and assessed the characteristics of the network. The aims of the study were: (1) to shed light on the pathological pathways between psychache and suicidal ideation, and between meaning in life and suicidal ideation; (2) to determine the critical central nodes that maintain the whole network; (3) to identify the predominant bridge nodes that connect different constructs; and (4) provide preliminary suggestions for the targeted prevention of, and interventions for suicidal ideation. Given that no study has investigated the fine relationships among the three constructs, our study is largely exploratory and extends the research field.

Methods

Participants and ethical approval

This study used an online survey hosted on the Wenjuanxing platform (www.wjx.cn). A total of 800 adults aged 18 years and older were recruited through convenience sampling based on WeChat from 2 to 2022 to 9 June 2022. Participants were eligible for inclusion if they (1) were healthy based on self-report; (2) with no self-reported history of neurological or psychiatric illnesses; and (3) consented to participate in the study. Participants gave their electronic informed consent after being informed about the purpose and nature of the research and the rights and obligations of the researcher and participants. The anonymity of the study was emphasized to encourage honest responses. Finally, participants completed three self-report scales (see below). Of course, participants could discontinue the survey at any time. To control data quality, 62 surveys were excluded because they met the following criteria: (1) the time used to complete the survey was < 100 s suggesting it was completed without thinking about each question, and (2) concealment dimension score was ≥ 4 on the Self-rating Idea of Suicide Scale. Our study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xijing Hospital, Air Force Medical University.

Measures

Self-rating scale for suicidal ideation (SIOSS)

The 26-item SIOSS was used to measure suicidal ideation [48, 49]. It includes four dimensions: despair, optimism, sleep, and concealment, and items are answered with a “yes” or “no”. If the concealment dimension score is ≥ 4, the measurement is considered unreliable. If the total score of despair, optimism and sleep dimensions is ≥ 12, the participant is considered to have suicidal ideation, with higher scores indicative of stronger suicidal ideation. The optimism dimension represents the opposite connotations because only the answers indicating negative meanings score. For the convenience of understanding, this paper used pessimism dimension to re-label the optimism dimension. In this study, Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.77.

The psychache scale (PAS)

The Chinese version of PAS, a single-dimension questionnaire with a total of 13 items, was used to assess psychache [50, 51]. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always or 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The scale is used to evaluate the introspective experience of negative emotions such as guilt, despair, loss, and fear. The higher the total score of the scale, the greater the psychache perceived by the individual. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.96.

Chinese meaning in Life Questionnaire (C-MLQ)

MLQ was translated into Chinese and used to evaluate each participant’s meaning in life and his/her pursuit of it [28, 52]. It contains two dimensions: the presence of meaning in life and search for meaning in life. The scale has a total of 10 items that are rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = absolutely untrue to 7 = absolutely true. The higher the score, the higher the individual’s meaning in life. The Cronbach’s coefficient α of the total scale was 0.86 in our sample.

Network analysis

The network was estimated via Gaussian graphical model (GGM), which is an undirected network [53]. In the model, each dimension of the scales (SIOSS, PAS, C-MLQ) was regarded as a node, and the partial correlation between two nodes after statistically controlling for any influence from other nodes was regarded as an edge. The estimation of GGM was based on nonparametric Spearman correlations [54]. The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) and Extended Bayesian Information Criterion (EBIC) were used to regularize the GGM [55, 56]. In this process, the edge with small partial correlation was set to zero, thus edges were shrunk and the symptom network was sparser and easier to interpret [54, 55]. Meanwhile, setting the tuning parameter to 0.5 balances the sensitivity and specificity of extracting true edges well [54]. R-package qgraph was used to construct and visualize the network in this part [57].

The expected influence (EI) of each node was calculated as the centrality index using R-package qgraph [57]. The EI value indicates the importance of the node for the entire network, and the higher the EI, the more influential the node. Bridge expected influence (BEI) was calculated as the bridge centrality indicator by R-package networktools [45]. A higher BEI value means a higher risk of contagion from the current community to other communities. In the present network, nodes were divided into three communities prior to analysis: suicidal ideation (three nodes), meaning in life (two nodes) and psychache (one node). Moreover, the R-package mgm was used to calculate the predictability of each node, which is an indicator reflecting the degree to which the variance of a node can be explained by all of its neighboring nodes and the controllability of the network model [42].

The accuracy and stability of the network were evaluated via R-package Bootnet [39]. First, the accuracy of edge weights was examined with the bootstrapped 95% confidence interval (CI) based on 1000 bootstrap samples. A narrower CI indicates the estimation of the edge weights is more accurate [58]. Second, the correlation stability (CS) coefficient calculated by a case-dropping bootstrap approach (1000 bootstrap samples) was used to evaluate the stability of the estimations of EI and BEI. A value greater than 0.5 indicates strong stability [39]. Third, bootstrapped difference tests (1000 bootstrap samples) were conducted for testing the differences of edge weights, EIs, and BEIs.

Results

The mean age of the 738 participants was 23.51 ± 3.93 years (mean ± SD, range = 18–46 years), and the majority were aged 30 years and younger (93%), with only 7% aged older than 30. Most participants were male (n = 700, 94.8%). Thirty-four participants (4.6%) met the criteria to screen individuals with suicidal ideation. The mean scores, standard deviations, EI (raw values), BEI (raw values), and predictability for each variable are shown in Table 1.

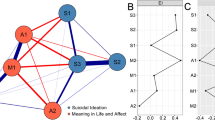

The final network is shown in Fig. 1, and several characteristics were apparent. First, there were 13 (86.67%) non-zero edges of 15 possible edges, including three negative and 10 positive edges. Second, the two strongest edges in the network structure appeared within the “suicidal ideation” and “meaning in life” communities. In the “suicidal ideation” community, the strongest edge was between “sleep” and “despair” (weight = 0.30). Within the “meaning in life” community, the second strongest edge (weight = 0.28) linked “presence of meaning in life” and “search for meaning in life”. Although relatively weak, some cross-community edges were also found. “Psychache” was positively linked to “sleep” and “despair”, with both edge weights equaling 0.26. “Presence of meaning in life” had negative associations with “psychache”, “despair”, and “pessimism” (weight = − 0.25, − 0.22, − 0.22, respectively). All edge weights of the present network can be seen in Supplementary Table 1. The bootstrapped 95% CI was narrow, suggesting that the estimation of edge weights was accurate and stable (Supplementary Fig. 1). The bootstrapped difference test for edge weights is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Third, predictability for each node was represented by a ring around it, and values ranged from 68 to 97%. The average node predictability was 81% (see Table 1), indicating 81% of the variance of the nodes could be explained by their neighboring nodes.

Node EI values were calculated to assess their relative importance in the current network (see Fig. 2a; Table 1). The nodes “sleep” (EI = 0.67) and “despair” (EI = 0.55) had the highest EI values, making them the most important central nodes. The CS coefficient for EI was 0.75, indicating the estimation of node EI had a good level of stability (see Supplementary Fig. 3). The result of the bootstrapped difference test for node EI is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4.

BEI values for each node are shown in Fig. 2b. In the “meaning of life” community, a critical bridge node was “presence of meaning in life” which exhibited the highest BEI with a value of − 0.69. Another critical bridge node was “psychache” (BEI = 0.38). The CS coefficient for BEI was 0.75, exceeding the preferable threshold of 0.5, signifying the estimation of BEI was adequately stable (see Supplementary Fig. 5). Supplementary Fig. 6 shows the result of the bootstrapped difference test for node BEI.

Discussion

While existing studies have demonstrated that psychache and meaning in life are associated with suicidal ideation [16, 27], the present study is the first to explore the fine-grained relationships among them via network analysis. Specifically, we examined the dimensional-level relationships between psychache and suicidal ideation, and between meaning in life and suicidal ideation. Our findings may facilitate our understanding of the specific pathological pathways underlying the close relationships between psychache, meaning in life and suicidal ideation. The study also identified the critical central nodes and bridge nodes that play important roles in developing and maintaining suicidal ideation, which suggest potential targets for prevention and intervention strategies to address suicidal ideation.

The results showed that the two strongest edges existed within the community. These findings are similar to previous network analysis studies that revealed the strongest edges existed within the community when examining network structures composed of different communities [40, 46, 59,60,61]. In addition to within-community edges, strong cross-community edges were also found, of which the edges between suicidal ideation and psychache or meaning in life were of most interest to us. The results revealed that “psychache” was positively associated with the “despair” and “sleep” dimensions of suicidal ideation, which may be the mechanisms underlying psychache as an important risk factor for developing suicidal ideation [17, 20, 23, 24]. This result is consistent with studies that suggest that considering suicide is a solution to escaping from unbearable psychache associated with feeling of despair caused by unfulfilled psychological needs such as security and accomplishment [17, 62]. As for the association between “psychache” and “sleep”, previous studies have shown that psychache aggravates the adverse effects of sleep disturbance on suicidal ideation and suicide attempts [63]. Since no studies have investigated the network structure of psychache and suicidal ideation, the current study provides a preliminary insight into their relationships and further studies are warranted.

We also found that “presence of meaning in life” had strong negative connections with the “despair” and “pessimism” dimensions of suicidal ideation, which is consistent with previously reported findings that meaning in life has a positive effect on preventing suicidal ideation and suicide [25,26,27]. Previous research has also suggested that individuals confused about meaning in their life are highly likely to experience despair and think about suicide [64,65,66]. One study has also proposed that creating moments of meaning in life can reduce despair [67]. Our finding is also consistent with previous studies that have shown the presence of meaning in life contributes to decreased suicidal ideation and is a protective factor against suicide [26, 27]. Furthermore, a multinational study found that meaning in life was positively related with optimism via multivariate analysis [68], which is also consistent with our finding of a negative relationship between “presence of meaning in life” and “pessimism”. Additionally, our results showed that “presence of meaning in life” was negatively related to “psychache”, which accords with the results of previous studies [31, 32]. It demonstrates another potential mechanism for the protective role of meaning in life in decreasing suicidal ideation: “presence of meaning in life” indirectly decreases suicidal ideation via its negative association with psychache — a susceptibility factor for suicidal ideation. The average predictability of the whole network was 81%, implying that the current network is more likely to be self-determined [42, 59].

The expected influence result showed that the dominant central nodes were the “sleep” and “despair” dimensions of suicidal ideation, meaning that “sleep” and “despair” exert great influence on the network. This is partly consistent with a previous study that showed sleep symptoms were central within the suicidal ideation networks of both males and females [69]. However, few studies have investigated suicidal ideation at a dimensional level, and most network studies regard suicidal ideation as a symptom of depression only [70, 71], and are therefore, not directly comparable with our study. Our finding that “sleep” and “despair” are central nodes is largely exploratory and is worth further consideration and investigation. Additionally, we calculated the bridge expected influence for each node to identify critical bridge nodes, and the results indicated that “presence of meaning in life” and “psychache” were bridge nodes. Our finding that “presence of meaning in life” was negatively linked to “despair”, “pessimism”, and “psychache”, indicates that presence of meaning in life prevents the despair and pessimism dimensions of suicidal ideation, and decreases psychache to reduce suicidal ideation. These findings are also consistent with previous studies [32, 67, 68]. However, we found “psychache” was the opposite case in the current study, indicating that individuals with psychache are susceptible to suicidal ideation.

The current study has important theoretical and clinical implications. Regarding the theoretical implications, these findings provide preliminary insights into the potential pathological pathways linking between psychache, meaning in life and suicidal ideation, furthering our understanding of the mechanisms underlying their relationships. Our findings are of great importance to figure out specific roles played by different dimensions of meaning in life or psychache in the development and maintenance of dimensions of suicidal ideation. In detail, this study suggests that the positive relationships between “psychache” and “sleep” or “despair” may explain how psychache contributes to suicidal ideation. Moreover, our study further suggests a possible pathway by which the meaning in life may reduce suicidal ideation, i.e., through the negative effect of “presence of meaning in life” on “despair” or “pessimism” dimensions of suicidal ideation. Additionally, the negative association between “presence of meaning in life” and “psychache” also indirectly accounts for the protective effect of meaning in life on decreasing suicidal ideation. Regarding the clinical implications, these findings provide an important reference for developing the strategies of clinical prevention and intervention for coping with suicidal ideation. Central nodes play an important role in activating other symptoms and developing and maintaining mental disorders, and exert a great influence on the whole psychopathological network [38, 72, 73]. Therefore, central nodes are regarded as promising targets for effective intervention [40, 46, 61, 74]. In our study, “sleep” and “despair” played the most important roles in the activation and maintenance of the network of suicidal ideation, psychache, and meaning in life, and hence, interventions targeting these two dimensions may effectively attenuate suicidal ideation and psychache. Similarly, bridge nodes are critical for the co-occurrence of psychopathological constructs and facilitate the impacts of one construct on others; therefore, bridge nodes are also considered targets for prevention and intervention [40, 44, 45, 47, 75]. In our study, “presence of meaning in life” and “psychache” were both identified as crucial bridge nodes for developing and maintaining suicidal ideation, indicating they might be promising targets for intervention. Controlling the adverse influence of “psychache”, as well as enhancing the protective effect of “presence of meaning in life” on suicidal ideation might increase the effectiveness of prevention and intervention strategies to mitigate suicidal ideation and suicide risk.

Although these findings are important, several limitations should be noted. First, due to the cross-sectional design of our study, we cannot make any inferences regarding causality between any of the constructs examined. Longitudinal or experimental studies are needed to examine the causal relationships among the constructs. Second, the study sample was mainly young male adults, which led to the uneven distribution of the age and sex, weakening the representativeness of the participants and limiting generalizability of our findings. Hence, future studies are required to include more females and other age groups in the analysis and the applicability of our results to other populations also requires replication in other samples. Third, the data was collected via self-report scales. Therefore, the results may have been influenced by recall bias [61, 76], and our findings should be interpreted with caution. Fourth, we used only one scale to measure each construct, and we may not have included all dimensions of those constructs. The current study only provided limited insight into their relationships, and future research using other scales that include other dimensions of the constructs are needed to comprehensively investigate how psychache and meaning in life develop and maintain suicidal ideation. Fifth, the self-report nature of our study may also hamper the validity of exclusion criteria. For example, individuals with depression can be included if they self-reported them as non-psychiatric; and the nodes “sleep” and “despair” happened to be symptoms of a current depressive episode, which is a reasonable mediator of suicidal ideation. This may add confounding factors to our study and undermine the quality and validity of our findings, which reminds us to interpret the findings cautiously. Sixth, although online recruitment and survey benefited us a lot, such as obtaining a large amount of data in a short time, saving a lot of manpower and resources, and reducing the effect of social approval due to its anonymity, it also introduced some challenges. For example, respondents are clustered in the younger population because the younger adults use the Internet and WeChat more often, which can also result in the sample of studies having risk of bias. Finally, although we identified some central and bridge nodes that might be potential targets for preventing suicidal ideation and intervening against it, the effectiveness of any such treatments requires thorough investigation and evaluation.

Conclusion

This study presents the first application of network analysis to investigate the relationships between suicidal ideation, psychache, and meaning in life in a joint framework. Our findings confirm the close relationship between both psychache and meaning in life, and suicidal ideation (the former being a risk factor and the latter a protective factor) at a dimensional level. The identification of “sleep” and “despair” as predominant central nodes and “presence of meaning in life” and “psychache” as critical bridge nodes have important clinical applications insofar as these nodes may be potential targets for effectively preventing and intervening against suicidal ideation.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SIOSS:

-

Self-Rating Scale for Suicidal Ideation

- PAS:

-

The Psychache Scale

- C-MLQ:

-

Chinese Meaning in Life Questionnaire

- GGM:

-

Gaussian graphical model

- LASSO:

-

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- EBIC:

-

Extended Bayesian Information Criterion

- EI:

-

Expected influence

- BEI:

-

Bridge expected influence

- Pre:

-

Predictability

- MLQ-P:

-

Presence of meaning in life

- MLQ-S:

-

Search for meaning in life

References

Ramirez Arango YC, Florez Jaramillo HM, Cardona Arango D, Segura Cardona AM, Segura Cardona A, Munoz Rodriguez DI, Lizcano Cardona D, Morales Mesa SA, Arango Alzate C, Agudelo Cifuentes MC. Factors Associated with suicidal ideation in older adults from three cities in Colombia, 2016. Revista Colombiana de psiquiatria (English ed). 2020;49(3):142–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcp.2018.09.004.

Park SM, Cho SI, Moon SS. Factors associated with suicidal ideation: role of emotional and instrumental support. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69(4):389–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.03.002.

Coentre R, Gois C. Suicidal ideation in medical students: recent insights. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:873–80. https://doi.org/10.2147/amep.S162626.

Wei S, Li H, Hou J, Chen W, Tan S, Chen X, Qin X. Comparing characteristics of suicide attempters with suicidal ideation and those without suicidal ideation treated in the emergency departments of general hospitals in China. Psychiatry Res. 2018;262:78–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.02.007.

Buddeberg C, Buddeberg-Fischer B, Gnam G, Schmid J, Christen S. Suicidal behavior in swiss students: an 18-month follow-up survey. Crisis. 1996;17(2):78–86. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910.17.2.78.

Isometsä E, Heikkinen M, Marttunen M, Henriksson M, Aro H, Lönnqvist J. The last appointment before suicide: is suicide intent communicated? Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(6):919–22. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.152.6.919.

Hubers AAM, Moaddine S, Peersmann SHM, Stijnen T, van Duijn E, van der Mast RC, Dekkers OM, Giltay EJ. Suicidal ideation and subsequent completed suicide in both psychiatric and non-psychiatric populations: a meta-analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatric Sci. 2018;27(2):186–98. https://doi.org/10.1017/s2045796016001049.

Batterham PJ, Calear AL, Mackinnon AJ, Christensen H. The association between suicidal ideation and increased mortality from natural causes. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(3):855–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.03.018.

DeBeer BB, Kittel JA, Cook A, Davidson D, Kimbrel NA, Meyer EC, Gulliver SB, Morissette SB. Predicting suicide risk in Trauma exposed Veterans: the role of Health promoting behaviors. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167464.

Large M, Corderoy A, McHugh C. Is suicidal behaviour a stronger predictor of later suicide than suicidal ideation? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2021;55(3):254–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867420931161.

Velupillai S, Epstein S, Bittar A, Stephenson T, Dutta R, Downs J. Identifying suicidal adolescents from Mental Health Records using Natural Language Processing. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2019;264:413–7. https://doi.org/10.3233/shti190254.

Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, Bruffaerts R, Chiu WT, de Girolamo G, Gluzman S, et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(2):98–105. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113.

Perera S, Eisen R, Bawor M, Dennis B, de Souza R, Thabane L, Samaan Z. Association between body mass index and suicidal behaviors: a systematic review protocol. Syst Reviews. 2015;4:52–2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-015-0038-y.

Shneidman ES. Suicide as psychache. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;181(3):145–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199303000-00001.

Verrocchio MC, Carrozzino D, Marchetti D, Andreasson K, Fulcheri M, Bech P. Mental Pain and suicide: a systematic review of the literature. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00108.

Montemarano V, Troister T, Lambert CE, Holden RR. A four-year longitudinal study examining psychache and suicide ideation in elevated-risk undergraduates: a test of Shneidman’s model of suicidal behavior. J Clin Psychol. 2018;74(10):1820–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22639.

Pereira AM, Campos RC. Exposure to suicide in the family and suicidal ideation in Portugal during the Covid-19 pandemic: the mediating role of unbearable psychache. Br J Clin Psychol. 2022;61(3):598–612. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12325.

Troister T, Holden RR. A two-year prospective study of psychache and its relationship to suicidality among high-risk undergraduates. J Clin Psychol. 2012;68(9):1019–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21869.

Troister T, Davis MP, Lowndes A, Holden RR. A five-month longitudinal study of psychache and suicide ideation: replication in general and high-risk university students. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2013;43(6):611–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12043.

Campos RC, Holden RR, Gomes M. Assessing psychache as a suicide risk variable: data with the portuguese version of the psychache scale. Death Stud. 2019;43(8):527–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2018.1493002.

Patterson AA, Holden RR. Psychache and suicide ideation among men who are homeless: a test of Shneidman’s model. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2012;42(2):147–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00078.x.

Ducasse D, Holden RR, Boyer L, Artero S, Calati R, Guillaume S, Courtet P, Olie E. Psychological Pain in Suicidality: a Meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(3). https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.16r10732.

Sun X, Li H, Song W, Jiang S, Shen C, Wang X. ROC analysis of three-dimensional psychological pain in suicide ideation and suicide attempt among patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychol. 2020;76(1):210–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22870.

Li X, You J, Ren Y, Zhou J, Sun R, Liu X, Leung F. A longitudinal study testing the role of psychache in the association between emotional abuse and suicidal ideation. J Clin Psychol. 2019;75(12):2284–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22847.

Marco JH, Canabate M, Perez S, Llorca G. Associations among meaning in life, body image, psychopathology, and suicide ideation in spanish participants with eating Disorders. J Clin Psychol. 2017;73(12):1768–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22481.

Kleiman EM, Beaver JK. A meaningful life is worth living: meaning in life as a suicide resiliency factor. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(3):934–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.08.002.

Lew B, Huen J, Yu P, Yuan L, Wang D-F, Ping F, Abu Talib M, Lester D, Jia C-X. Associations between depression, anxiety, stress, hopelessness, subjective well-being, coping styles and suicide in chinese university students. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217372.

Steger MF, Frazier P, Oishi S, Kaler M. The meaning in life questionnaire: assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J Couns Psychol. 2006;53(1):80–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80.

Heintzelman SJ, King LA. Life is pretty meaningful. Am Psychol. 2014;69(6):561–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035049.

Whitlock J, Muehlenkamp J, Eckenrode J, Purington A, Abrams GB, Barreira P, Kress V. Nonsuicidal Self-Injury as a gateway to suicide in young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(4):486–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.010.

Orbach I, Mikulincer M, Gilboa-Schechtman E, Sirota P. Mental pain and its relationship to suicidality and life meaning. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2003;33(3):231–41. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.33.3.231.23213.

Ostafin BD, Proulx T. Meaning in life and resilience to stressors. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2020;33(6):603–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1800655.

Fried EI. Problematic assumptions have slowed down depression research: why symptoms, not syndromes are the way forward. Front Psychol. 2015;6:309. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00309.

Fried EI, Epskamp S, Nesse RM, Tuerlinckx F, Borsboom D. What are ‘good’ depression symptoms? Comparing the centrality of DSM and non-DSM symptoms of depression in a network analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;189:314–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.005.

Chen Q, Wang X-Q, He X-X, Ji L-J, Liu M-f. Ye B-j. The relationship between search for meaning in life and symptoms of depression and anxiety: key roles of the presence of meaning in life and life events among chinese adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2021;282:545–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.156.

Fried EI, Nesse RM. Depression sum-scores don’t add up: why analyzing specific depression symptoms is essential. BMC Med. 2015;72(13). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0325-4.

Borsboom D, Cramer AOJ. Network Analysis: An Integrative Approach to the Structure of Psychopathology. In: Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, Vol 9. Volume 9, edn. Edited by NolenHoeksema S; 2013: 91–121.

McNally RJ. Can network analysis transform psychopathology? Behav Res Ther. 2016;86:95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.06.006.

Borsboom D. A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):5–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20375.

Epskamp S, Borsboom D, Fried EI. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: a tutorial paper. Behav Res Methods. 2018;50(1):195–212. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0862-1.

Haws JK, Brockdorf AN, Gratz KL, Messman TL, Tull MT, DiLillo D. Examining the associations between PTSD symptoms and aspects of emotion dysregulation through network analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2022;86:102536–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102536.

Skjerdingstad N, Johnson MS, Johnson SU, Hoffart A, Ebrahimi OV. Feelings of worthlessness links depressive symptoms and parental stress: a network analysis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur PSYCHIATRY. 2021;64(1). https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.2223.

Haslbeck JMB, Fried EI. How predictable are symptoms in psychopathological networks? A reanalysis of 18 published datasets. Psychol Med. 2017;47(16):2767–76. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291717001258.

Huang S, Lai X, Xue Y, Zhang C, Wang Y. A network analysis of problematic smartphone use symptoms in a student sample. J Behav Addictions. 2020;9(4):1032–43. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00098.

Byrne ME, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Lavender JM, Parker MN, Shank LM, Swanson TN, Ramirez E, LeMay-Russell S, Yang SB, Brady SM, et al. Bridging executive function and disinhibited eating among youth: a network analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 2021;54(5):721–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23476.

Jones PJ, Ma R, McNally RJ. Bridge centrality: A Network Approach to understanding Comorbidity. Multivar Behav Res. 2021;56(2):353–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2019.1614898.

Cai H, Bai W, Sha S, Zhang L, Chow IHI, Lei S-M, Lok GKI, Cheung T, Su Z, Hall BJ, et al. Identification of central symptoms in internet addictions and depression among adolescents in Macau: a network analysis. J Affect Disord. 2022;302:415–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.068.

Yuan GF, Shi W, Elhai JD, Montag C, Chang K, Jackson T, Hall BJ. Gaming to cope: applying network analysis to understand the relationship between posttraumatic stress symptoms and internet gaming disorder symptoms among disaster-exposed chinese young adults. Addict Behav. 2022;124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107096.

Cheng X, Zhang Y, Zhao D, Yuan T-F, Qiu J. Trait anxiety mediates impulsivity and suicidal ideation in Depression during COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.892442.

Xia CY, Wang DB, He XD, Ye SH. Study of self-rating idea of undergraduates in the mountain area of southern Zhejiang. Chin J Sch Health. 2012;33(2):144–6.

Yang L, Chen W. Reliability and validity of the Psychache Scale in Chinese Undergraduates. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2017;25(3):475–8583.

Holden RR, Mehta, Karishma, Cunningham JE, McLeod, Lindsay D. Development and preliminary validation of a scale of psychache. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement 2001.

Wang M, Dai X. Chinese meaning in Life Questionnaire revised in College Students and its reliability and validity test. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2008;16(5):459–61.

Epskamp S, Waldorp LJ, Mottus R, Borsboom D. The gaussian graphical model in cross-sectional and Time-Series Data. Multivar Behav Res. 2018;53(4):453–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2018.1454823.

Epskamp S, Fried E. A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychol Methods. 2018;23(4):617–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000167.

Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Sparse inverse covariance estimation with the graphical lasso. Biostatistics (Oxford England). 2008;9(3):432–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/biostatistics/kxm045.

Foygel R, Drton M. Extended bayesian information criteria for gaussian graphical models. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2010;23:2020–8.

Epskamp S, Cramer A, Waldorp LJ, Schmittmann VD, Borsboom D. qgraph: network visualizations of Relationships in Psychometric Data. J Stat Softw. 2012;48(4):367–71. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i04.

Mullarkey M, Marchetti I, Beevers C. Using Network Analysis to identify central symptoms of adolescent depression. J Clin child Adolesc psychology: official J Soc Clin Child Adolesc Psychol Am Psychol Association Div. 2019;53(4):656–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2018.1437735.

Ren L, Wang Y, Wu L, Wei Z, Cui L-B, Wei X, Hu X, Peng J, Jin Y, Li F, et al. Network structure of depression and anxiety symptoms in chinese female nursing students. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03276-1.

Gao L, Zhao W, Chu X, Chen H, Li W. A Network analysis of the Relationships between behavioral Inhibition/Activation Systems and Problematic Mobile phone use. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:832933. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.832933.

Liu C, Ren L, Li K, Yang W, Li Y, Rotaru K, Wei X, Yuecel M, Albertella L. Understanding the Association between intolerance of uncertainty and problematic smartphone use: A Network Analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.917833.

Orbach I, Mikulincer M, Sirota P, Gilboa-Schechtman E. Mental pain: a multidimensional operationalization and definition. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2003;33(3):219–30. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.33.3.219.23219.

Ugur K, Demirkol ME, Tamam L. The Mediating Roles of Psychological Pain and dream anxiety in the relationship between Sleep disturbance and suicide. Archives of suicide research: official journal of the International Academy for Suicide Research. 2021;25(3):512–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2020.1740124.

Buchanan CM, Maccoby EE, Dornbusch SM. Caught between parents: adolescents’ experience in divorced homes. Child Dev. 1991;62(5):1008–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01586.x.

Liu Y, Usman M, Zhang J, Gul H. Making sense of chinese employees’ suicidal ideation: a psychological strain-life meaning model. Psychol Rep. 2020;123(2):201–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294118811096.

Bowes DE, Tamlyn D, Butler LJ. Women living with ovarian cancer: dealing with an early death. Health Care Women Int. 2002;23(2):135–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/073993302753429013.

Attoe AD, Chimakonam JO. The Covid-19 pandemic and meaning in life. Phronimon. 2020;21(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.25159/2413-3086/8420.

Gravier AL, Shamieh O, Paiva CE, Perez-Cruz PE, Muckaden MA, Park M, Bruera E, Hui D. Meaning in life in patients with advanced cancer: a multinational study. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(8):3927–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05239-5.

Ma S, Yang J, Xu J, Zhang N, Kang L, Wang P, Wang W, Yang B, Li R, Xiang D, et al. Using network analysis to identify central symptoms of college students’ mental health. J Affect Disord. 2022;311:47–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.05.065.

Feiten JG, Mosqueiro BP, Uequed M, Passos IC, Fleck MP, Caldieraro MA. Evaluation of major depression symptom networks using clinician-rated and patient-rated data. J Affect Disord. 2021;292:583–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.102.

Wei Z, Ren L, Wang X, Liu C, Cao M, Hu M, Jiang Z, Hui B, Xia F, Yang Q, et al. Network of depression and anxiety symptoms in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2021;175:106696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2021.106696.

Robinaugh D, Millner A, McNally R. Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. J Abnorm Psychol. 2016;125(6):747–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000181.

Mancinelli E, Ruocco E, Napolitano S, Salcuni S. A network analysis on self-harming and problematic smartphone use - the role of self-control, internalizing and externalizing problems in a sample of self-harming adolescents. Compr Psychiatr. 2022;112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2021.152285.

Yuan H, Ren L, Ma Z, Li F, Liu J, Jin Y, Chen C, Li X, Wu Z, Cheng S, et al. Network structure of PTSD symptoms in chinese male firefighters. Asian J Psychiatr. 2022;72:103062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2022.103062.

Guo Z, Liang S, Ren L, Yang T, Qiu R, He Y, Zhu X. Applying network analysis to understand the relationships between impulsivity and social media addiction and between impulsivity and problematic smartphone use. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.993328.

Yang Y, Zhang D-Y, Li Y-L, Zhang M, Wang P-H, Liu X-H, Ge L-N, Lin W-X, Xu Y, Zhang Y-L, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and network analysis of internet addiction symptoms among chinese pregnant and postpartum women. J Affect Disord. 2022;298:126–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.092.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the individuals who participated in the study. The authors also thank MogoEdit (https://www.mogoedit.com) for its English editing during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key project of PLA Logistics Research Program during the 14th Five-Year Plan period (BKJ21J013); the PLA military medical innovation key project (18CXZ012); and Air Force Medical University military medical Mount Everest project (2019rcfcwsj).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yijun Li: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing - original draft. Zhihua Guo: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft. Wenqing Tian: Data curation, Writing - original draft. Xiuchao Wang: Investigation, Methodology, Visualization. Jiawei Dou: Investigation, Methodology. Yanfeng Chen: Resources, Data curation, Investigation. Shen Huang: Resources, Data curation, Investigation. Shengdong Ni: Formal analysis, Visualization. Hui Wang: Formal analysis, Visualization. Chaoxian Wang: Resources. Xufeng Liu: Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing, Project administration. Xia Zhu: Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing, Project administration. Shengjun Wu: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing, Project administration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards put forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The study design and procedures were reviewed and approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of the Fourth Military Medical University(Batch number: KY20202063-F-2).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Guo, Z., Tian, W. et al. An investigation of the relationships between suicidal ideation, psychache, and meaning in life using network analysis. BMC Psychiatry 23, 257 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04700-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04700-4