Abstract

Background

Perinatal depression in women is associated with high morbidity and mortality, and has attracted increasing attention. The investigation of risk factors of perinatal depression in women may contribute to the early identification of depressed or depression-prone women in clinical practice.

Material and Methods

A computerized systematic literature search was made in Cochrane Library, PubMed, Web of Science, and EMBASE from January 2009 to October 2021. All included articles were published in English, which evaluated factors influencing perinatal depression in women. Based on the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration protocols, Review Manager 5.3 was used as a statistical platform.

Results

Thirty-one studies with an overall sample size of 79,043 women were included in the review. Educational level (P = 0.0001, odds ratio [OR]: 1.40, 95% CI: [1.18,1.67]), economic status of families (P = 0.0001, OR: 1.69, 95%CI: [1.29,2.22]), history of mental illness (P < 0.00001, OR: 0.29, 95% CI: [0.18, 0.47]), domestic violence (P < 0.00001, OR: 0.24, 95% CI: [0.17,0.34]), perinatal smoking or drinking (P = 0.005, OR: 0.63; 95% CI [0.45, 0.87]; P = 0.008, OR: 0.43, 95% CI, [0.23 to 0.80]; respectively), and multiparity(P = 0.0003, OR: 0.74, 95% CI: [0.63, 0.87]) were correlated with perinatal depression in women. The stability of our pooled results was verified by sensitivity analysis and publication bias was not observed based on funnel plot results.

Conclusion

Lower educational level, poor economic status of families, history of mental illness, domestic violence, perinatal smoking or drinking, and multiparity serve as risk factors of perinatal depression in women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Perinatal depression refers to severe depressive episodes during pregnancy and/or within 12 months postpartum, and is one of the most common reproductive complications [1, 2]. The prevalence of perinatal depression in women is about 10–15% in developed countries, and a higher risk in less-developed countries [3, 4]. One research has suggested that nearly a fifth of women experience depression during pregnancy [5]. Perinatal depression has been shown associated with poorer pregnancy outcomes and long-standing emotional, social and cognitive difficulties in children [6]. Furthermore, perinatal depression in women is correlated with high morbidity and mortality, which imposes a massive burden on the affected individual, family members and society.

In the current study, a large number of studies have focused on the risk factors of perinatal depression in women. Several studies have suggested that many possible influencing factors related to perinatal depression in women, such as lower educational level, younger maternal age, smoking during the pregnancy, a history of depression, poor economic status of families, worse marriage status, adverse life events, antenatal depression and anxiety, and lack of social support, etc.[7,8,9,10]. However, the results of some studies remain controversial. For example, Furtado et al. reported that the maternal education level was not correlated with perinatal depression, while Martini et al. demonstrated that low education level was a significant negative factor in perinatal depression [11, 12]. Hence, in this study, we aim to present an overview of the risk factors of perinatal depression in women through a systemic review and meta-analysis.

Material and Methods

Eligibility criteria

This meta-analysis followed the PRISMA statement criteria [13], and the meta-analysis was not pre-registered. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for literature were determined prior to the study selection process and are described as follows:

Inclusion criteria:

-

1.

English-written and officially published trials from January 2009 to October 2021;

-

2.

Compare the effects of different factors on depression in perinatal women;

-

3.

Available raw data of interested indicators;

-

4.

Quantitative analysis of raw data by professional scales.

-

5.

Exclusion criteria:

-

6.

Duplicated or overlapping studies;

-

7.

Insufficient scale of sample size (< 100);

-

8.

Inappropriate article types such as case reports or reviews.

Using predefined criteria, row data were extracted by two researchers from tables, text contents and supplementary information within each included study, respectively.

Literature retrieval

To guarantee the completeness of literature search, databases of Cochrane Library, PubMed, Web of Science, and EMBASE were carefully screened using the Search strategies ((Depressive Symptoms) OR (Depressive Symptom) OR (Symptom, Depressive) OR (Symptoms, Depressive) OR (Emotional Depression) OR (Depression, Emotional) OR (Depression)) AND ((Perinatal) OR (Perinatal period)) from January 2009 to October 2021. The literature search was conducted by two investigators independently. Abstracts, full-texts, and reference lists were elaborately examined to avoid unnecessary omission or ineligible inclusion during the retrieval process.

Methodological assessment.

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was applied to qualitatively evaluate the included study [14]. The whole scale had a maximum score of 9 points and was composed of three items: selection, comparability and outcome. The study that scored more than 6 on our assessment using NOS methods were identified as a high-quality trial.

Statistical analysis

All statistical processes are based on the Cochrane Collaboration protocols, that is, Review Manager 5.3 was used as a statistical software for quantitative analysis. The models of odds ratio along with 95% confidence interval were used to illustrate the effect sizes of the dichotomous variables. Heterogeneity of endpoints was measured by I2. The outcome definition of I2 values consisted low (< 25%), moderate (25%-50%), and high (> 50%) heterogeneity [15]. When I2 values were < 25%, a fixed-effects model was used, otherwise, a random-effects model was preferred in the remaining cases to adjust for potential differences across individual studies. To further explore the source of heterogeneity, we separately divided the primary endpoints into multiple subgroups based on different variables. Sensitivity analysis was presented by removing low-quality studies in order to observe the outcome stability. Publication bias was analyzed by evaluating the funnel plots. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study and patient characteristics

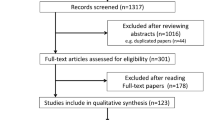

Among 14,216 retrieved records, 31 studies were included in the quantitative analysis (Fig. 1). The total sample size consisted of 79,043 patients, with individual participants in each study ranging from 103 to 34,633 with a median of 564. There were 18 studies in developing countries and 13 trials in developed countries, with England accounting for the largest number of 5. Other detailed features are listed in Table 1 [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46].

Methodological assessment

All included studies had NOS scores of 5 to 9, and the results of evaluation comprised four 5-score studies, eight 6-score studies, eleven 7-score studies, six 8-score studies, and two 9-score studies. Of these, the studies of 5 points included wang 2010, Clarke 2014, Maggie 2013 m and Suad 2009, the important reasons for these studies of low scores were unclear evaluation methods and fewer included studies entries (Table 1).

Social and economic factors

For this part, maternal age, pregnancy planning, marriage status, maternal education level, family economic status, and maternal employment status were included in the further meta-analysis. The results indicate that maternal education level and family economic status were the risk factors of perinatal depression, while maternal age, pregnancy planning, marriage status, and maternal employment status were not significantly associated with perinatal depression (Table 2).

Specifically, twenty-four studies provided row data on perinatal depression with different maternal education levels. Compared with higher education levels, perinatal women with lower education levels were significantly more susceptible to depression, along with high heterogeneity of source uncertainty (P = 0.0001, OR: 1.40, 95% CI: [1.18,1.67], I2 = 85%) (Fig. 2). Subgroup analysis by countries with different economic levels showed that perinatal women from developing nations (P = 0.008, OR: 1.38, 95% CI: [1.09,1.76], I2 = 54%) or developed country (P = 0.006, OR: 1.43, 95% CI: [1.11,1.84], I2 = 93%), lower education level were associated with increased depression (Table 3).

In addition, raw data of perinatal depression in various family economic status was obtained from 13 studies. Our pooled results indicated that poorer family economic status was significantly correlated with depression in perinatal women (P = 0.0001, OR: 1.69, 95%CI: [1.29,2.22], I2 = 79%) (Fig. 3). As for the source regions of perinatal women with depression, poorer family economic status was significantly related to increased depression from developing nations (P = 0.002, OR: 1.82, 95% CI: [1.24, 2.66], I2 = 80%) and developed country (P = 0.0008, OR: 1.30, 95% CI: [1.12, 1.51], I2 = 0%). Regarding subgroups of different country incomes, our pooled results showed that poorer family economies were strongly associated with increased depression in perinatal women (Table 3).

Family environment and past medical history

we next counted and evaluated the impact of the past mental health history of perinatal women and domestic violence on depression. The original data from 11 studies on the correlations between psychiatric history and perinatal depression were extracted. The pooled results showed that there was a significant correlation between the history of previous mental illness and depression in perinatal women (P < 0.00001, OR: 0.29, 95% CI: [0.18, 0.47]) (Fig. 4). High heterogeneity of unknown sources was observed (I2 = 89%). Depending on the countries with different economic levels, the included studies were divided into two subgroups. The history of previous mental illness was obviously associated with depression in perinatal women, regardless of whether perinatal women was from developing countries (P < 0.00001, OR: 0.24, 95% CI: [0.16, 0.37], I2 = 69%) or developed country (P = 0.02, OR: 0.36, 95% CI: [0.16, 0.82], I2 = 94%) (Table 3).

In addition, the meta-analysis of 11 studies demonstrated that domestic violence had a negative effect on depression in perinatal women (P < 0.00001, OR: 0.24, 95% CI: [0.17,0.34], I2 = 78%) (Fig. 5). Similarly, we performed a following subgroup analysis to elucidate the possible confounding factors. Based on subgroups analysis of different source regions, domestic violence in developed country (P < 0.00001, OR: 0.44, 95% CI: [0.32,0.60]) or developing nations (P < 0.00001, OR: 0.22, 95% CI: [0.14,0.32], I2 = 77%) contributed to a significantly depression in perinatal women (Table 3).

Maternal lifestyle.

In this part, we mainly focused on the impacts of maternal lifestyles including perinatal smoking and drinking on perinatal depression. Concerning smoking and drinking in perinatal women, only six and five studies offered original data, respectively. As a results, perinatal women with smoking (P = 0.005, OR: 0.63, 95% CI: [0.45,0.87]) or drinking (P = 0.008, OR: 0.43, 95% CI: [0.23,0.80]) were more prone to depression (Fig. 5). Moderate and high heterogeneity was observed respectively in both analyses (smoking: I2 = 26% and drinking: I2 = 66%). The subgroup analysis had not been further implemented due to fewer studies included.

Reproductive health factors

The original data about parity, cesarean section, premature birth, fetal gender, serious perinatal health problems (excluding hypertension or diabetes), and hypertension or diabetes were included in our meta-analysis. As shown in Table 2 and Fig. 6, the results indicated that parity was the influencing factor of perinatal depression, while cesarean section, premature birth, fetal gender, serious perinatal health problems (excluding hypertension or diabetes), and hypertension or diabetes were not significantly associated with perinatal depression.

Eighteen trials provided original data on depression in perinatal women in terms of parity. It demonstrated that perinatal women with multiparity were highly associated with perinatal depression (P = 0.0003, OR: 0.74, 95% CI: [0.63, 0.87], I2 = 48%) (Fig. 7). In the subgroup analysis by national economic level, a higher proportion of depression was observed among perinatal women with multiparity both in developing (P = 0.02, OR: 0.78, 95% CI: [0.63,0.96], I2 = 54%) and developed nations (P = 0.005, OR: 0.67, 95% CI: [0.50, 0.89], I2 = 87%) (Table 3).

Sensitivity analysis

As shown in Table 4, the elimination of studies with 5 points on the NOS assessment was unable to affect the negative outcome of the maternal low-education levels (P = 0.001, OR: 1.38, 95% CI: [1.13, 1.69], I2 = 86%), poor family economic status (P = 0.001, OR: 1.80, 95% CI: [1.27, 2.56], I2 = 81%), history of mental illness (P < 0.00001, OR: 0.33, 95% CI: [0.23, 0.47], I2 = 77%) and multiparity (P = 0.0006, OR: 0.72, 95% CI: [0.59, 0.87], I2 = 48%) on depression in perinatal women. Besides, the original data of the domestic violence, perinatal smoking and drinking did not include anyone of study with NOS score of 5, so we did not further conduct sensitivity analysis in other ways.

Publication bias

No obvious publication bias was observed in our meta-analysis results following funnel plots validation (Fig. 8).

Discussion

This meta-analysis examined the risk factors of perinatal depression. We found evidence supporting lower educational level, poor economic status of families, history of mental illness, domestic violence, perinatal smoking or drinking, and multiparity were associated with depression in perinatal women, regardless of the subgroup confounding variables.

Perinatal depression is no different from general depression and presents with a state of low mood, inactivity, fatigue, sleep disturbances, disconcertment, disorientation or suicidal thinking [16]. In addition, it was associated with poorer pregnancy outcomes and long-standing emotional, social and cognitive difficulties in children [47]. Prevention and early intervention in perinatal mental health have been identified as potentially important strategies, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines have recommended screening for perinatal depression at least once during the perinatal period [48, 49]. And The US Preventive Services Task Force suggested that counseling interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy, are effective in preventing perinatal depression [50]. However, lacking effective methods to identify women who are prone to perinatal depression remains a major obstacle.

Previous studies focused on a single influence (disease or region) on perinatal depression [51, 52]. In our current meta-analysis, some factors have been revealed to be inextricably linked to perinatal depression in women, which include lower educational level, poor economic status of families, history of mental illness, domestic violence and multiparity. Similar to our results, domestic violence is significantly associated with perinatal depression [53, 54]. And we novelty demonstrated that perinatal smoking or drinking increased the incidence of perinatal depression. It is acknowledged that people with mental health problems are more likely to smoke/drink which may, in turn, worsen mental health conditions [55]. Importantly, tobacco cessation may contribute to improved depressive symptoms of perinatal depression women.

Although Biaggi et al. reported that pregnancy complications were a risk factor for perinatal depression, further data collection was needed to clarify whether different complications had different effects on depression to further explain these controversies [56]. Based on our results, the association between reproductive health factors and perinatal depression was not observed. Medical literature also pointed out that the conditions of the delivery room usually increase the risk of maternal depression [57]. Improving the conditions of the delivery room is also an important measure to reduce the tendency of perinatal depression, especially for some developing countries. Of course, the above results are only reported in a few studies, and they are not analyzed as our combined results. In addition, many studies have compared the effects of cesarean section and vaginal delivery on perinatal depression, but there are few studies on the relationship between auxiliary intervention during vaginal delivery and perinatal depression. We look forward to more research results to confirm the link between auxiliary interventions during vaginal delivery, such as fetal monitoring, lateral perineal incision, perineal tear, catheterization and enema, etc. and perinatal depression. This will have obvious guiding significance for whether to carry out relevant auxiliary interventions during vaginal delivery.

Apart from the significant results, our quantitative meta-analysis has some limitations. First, despite the subgroup analysis, the heterogeneity of our study was not completely eliminated, which may lead to bias in the results to a certain extent. We suspected that heterogeneity mainly came from the following aspects: 1) The evaluation criteria of each study were not uniform. 2) Some factors cannot be integrated into our analysis, such as ethnicity. Secondly, although the total sample sizes exceeded 70,000, the influencing factors of some included studies were insufficient, leading to some potential influencing factors that cannot produce meaningful results. Taken together, despite the above shortcomings, our meta-analysis demonstrates several factors associated with depression in perinatal women. This is consistent with other studies in the field, highlighting the value of screening and monitoring these indicators of maternal. We recommend that our pooled results be used to prevent and clinically guide women with perinatal depression.

Conclusion

Perinatal women in the following cases: lower educational level, poor economic status of families, history of mental illness, domestic violence, perinatal smoking or drinking, and multiparity have a higher incidence of perinatal depression than without these conditions. Therefore, it is recommended that early screening and counseling interventions for those women to prevent perinatal depression.

Availability of data and materials

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

References

Alipour Z, Lamyian M, Hajizadeh E. Anxiety and fear of childbirth as predictors of postnatal depression in nulliparous women. Women Birth. 2012;25(3):e37-43.

Putnam KT, Wilcox M, Robertson-Blackmore E, Sharkey K, Bergink V, Munk-Olsen T, Deligiannidis KM, Payne J, Altemus M, Newport J, et al. Clinical phenotypes of perinatal depression and time of symptom onset: analysis of data from an international consortium. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(6):477–85.

Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5 Pt 1):1071–83.

Sawyer A, Ayers S, Smith H. Pre- and postnatal psychological wellbeing in Africa: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2010;123(1–3):17–29.

Faisal-Cury A, Menezes P, Araya R, Zugaib M. Common mental disorders during pregnancy: prevalence and associated factors among low-income women in Sao Paulo, Brazil: depression and anxiety during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12(5):335–43.

Parsons CE, Young KS, Rochat TJ, Kringelbach ML, Stein A. Postnatal depression and its effects on child development: a review of evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Br Med Bull. 2012;101:57–79.

O’Hara MW, McCabe JE. Postpartum depression: current status and future directions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:379–407.

Dagher RK, Shenassa ED. Prenatal health behaviors and postpartum depression: is there an association? Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(1):31–7.

Norhayati MN, Hazlina NH, Asrenee AR, Emilin WM. Magnitude and risk factors for postpartum symptoms: a literature review. J Affect Disord. 2015;175:34–52.

Liu S, Yan Y, Gao X, Xiang S, Sha T, Zeng G, He Q. Risk factors for postpartum depression among Chinese women: path model analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):133.

Furtado M, Van Lieshout RJ, Van Ameringen M, Green SM, Frey BN. Biological and psychosocial predictors of anxiety worsening in the postpartum period: A longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2019;250:218–25.

Martini J, Petzoldt J, Einsle F, Beesdo-Baum K, Hofler M, Wittchen HU. Risk factors and course patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders during pregnancy and after delivery: a prospective-longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2015;175:385–95.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9 (W264).

Lo CK, Mertz D, Loeb M. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:45.

Melsen WG, Bootsma MC, Rovers MM, Bonten MJ. The effects of clinical and statistical heterogeneity on the predictive values of results from meta-analyses. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(2):123–9.

Tariq N, Naeem H, Tariq A, Naseem S. Maternal depression and its correlates: A longitudinal study. JPMA. 2021;71(6):1618–22.

Raghavan V, Khan HA, Seshu U, Rai SP, Durairaj J, Aarthi G, Sangeetha C, John S, Thara R. Prevalence and risk factors of perinatal depression among women in rural Bihar: A community-based cross-sectional study. Asian J Psychiatry. 2021;56:102552.

Joshi D, Shrestha S, Shrestha N. Understanding the antepartum depressive symptoms and its risk factors among the pregnant women visiting public health facilities of Nepal. PloS One. 2019;14(4):e0214992.

Azad R, Fahmi R, Shrestha S, Joshi H, Hasan M, Khan ANS, Chowdhury MAK, Arifeen SE, Billah SM. Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression within one year after birth in urban slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh. PloS One. 2019;14(5):e0215735.

Faisal-Cury A, Menezes PR, Quayle J, Matijasevich A. Unplanned pregnancy and risk of maternal depression: secondary data analysis from a prospective pregnancy cohort. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22(1):65–74.

Inglis AJ, Hippman CL, Carrion PB, Honer WG, Austin JC. Mania and depression in the perinatal period among women with a history of major depressive disorders. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17(2):137–43.

Bell AF, Carter CS, Davis JM, Golding J, Adejumo O, Pyra M, Connelly JJ, Rubin LH. Childbirth and symptoms of postpartum depression and anxiety: a prospective birth cohort study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19(2):219–27.

Chandrasekaran N, De Souza LR, Urquia ML, Young B, McLeod A, Windrim R, Berger H. Is anemia an independent risk factor for postpartum depression in women who have a cesarean section? - A prospective observational study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):400.

Chong MF, Wong JX, Colega M, Chen LW, van Dam RM, Tan CS, Lim AL, Cai S, Broekman BF, Lee YS, et al. Relationships of maternal folate and vitamin B12 status during pregnancy with perinatal depression: The GUSTO study. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;55:110–6.

Cirik DA, Yerebasmaz N, Kotan VO, Salihoglu KN, Akpinar F, Yalvac S, Kandemir O. The impact of prenatal psychologic and obstetric parameters on postpartum depression in late-term pregnancies: A preliminary study. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;55(3):374–8.

Clarke K, Saville N, Shrestha B, Costello A, King M, Manandhar D, Osrin D, Prost A. Predictors of psychological distress among postnatal mothers in rural Nepal: a cross-sectional community-based study. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:76–86.

Duman B, Senturk Cankorur V, Taylor C, Stewart R. Prospective associations between recalled parental bonding and perinatal depression: a cohort study in urban and rural Turkey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(4):385–92.

Melo EF Jr, Cecatti JG, Pacagnella RC, Leite DF, Vulcani DE, Makuch MY. The prevalence of perinatal depression and its associated factors in two different settings in Brazil. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):1204–8.

Gressier F, Guillard V, Cazas O, Falissard B, Glangeaud-Freudenthal NM, Sutter-Dallay AL. Risk factors for suicide attempt in pregnancy and the post-partum period in women with serious mental illnesses. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;84:284–91.

Davey HL, Tough SC, Adair CE, Benzies KM. Risk factors for sub-clinical and major postpartum depression among a community cohort of Canadian women. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(7):866–75.

Husain N, Parveen A, Husain M, Saeed Q, Jafri F, Rahman R, Tomenson B, Chaudhry IB. Prevalence and psychosocial correlates of perinatal depression: a cohort study from urban Pakistan. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14(5):395–403.

Husain N, Cruickshank K, Husain M, Khan S, Tomenson B, Rahman A. Social stress and depression during pregnancy and in the postnatal period in British Pakistani mothers: a cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2012;140(3):268–76.

Rogathi JJ, Manongi R, Mushi D, Rasch V, Sigalla GN, Gammeltoft T, Meyrowitsch DW. Postpartum depression among women who have experienced intimate partner violence: A prospective cohort study at Moshi Tanzania. J Affect Disord. 2017;218:238–45.

Kozhimannil KB, Pereira MA, Harlow BL. Association between diabetes and perinatal depression among low-income mothers. JAMA. 2009;301(8):842–7.

Koutra K, Vassilaki M, Georgiou V, Koutis A, Bitsios P, Kogevinas M, Chatzi L. Pregnancy, perinatal and postpartum complications as determinants of postpartum depression: the Rhea mother-child cohort in Crete Greece. Epidemiol Psychiatric Sci. 2018;27(3):244–55.

Li Y, Long Z, Cao D, Cao F. Social support and depression across the perinatal period: A longitudinal study. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(17–18):2776–83.

Redshaw M, Henderson J. From antenatal to postnatal depression: associated factors and mitigating influences. J Womens Health (2002). 2013;22(6):518–25.

Nyamukoho E, Mangezi W, Marimbe B, Verhey R, Chibanda D. Depression among HIV positive pregnant women in Zimbabwe: a primary health care based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):53.

Rurangirwa AA, Mogren I, Ntaganira J, Govender K, Krantz G. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy in relation to non-psychotic mental health disorders in Rwanda: a cross-sectional population-based study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e021807.

SenturkCankorur V, Duman B, Taylor C, Stewart R. Gender preference and perinatal depression in Turkey: A cohort study. PloS One. 2017;12(3):e0174558.

Sheeba B, Nath A, Metgud CS, Krishna M, Venkatesh S, Vindhya J, Murthy GVS. Prenatal Depression and Its Associated Risk Factors Among Pregnant Women in Bangalore: A Hospital Based Prevalence Study. Front Public Health. 2019;7:108.

Shi P, Ren H, Li H, Dai Q. Maternal depression and suicide at immediate prenatal and early postpartum periods and psychosocial risk factors. Psychiatry Res. 2018;261:298–306.

Kapetanovic S, Christensen S, Karim R, Lin F, Mack WJ, Operskalski E, Frederick T, Spencer L, Stek A, Kramer F, et al. Correlates of perinatal depression in HIV-infected women. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(2):101–8.

Tefera TB, Erena AN, Kuti KA, Hussen MA. Perinatal depression and associated factors among reproductive aged group women at Goba and Robe Town of Bale Zone, Oromia Region, South East Ethiopia. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2015;1:12.

Tong VT, Farr SL, Bombard J, D’Angelo D, Ko JY, England LJ. Smoking Before and During Pregnancy Among Women Reporting Depression or Anxiety. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):562–70.

Wang SY, Chen CH. The association between prenatal depression and obstetric outcome in Taiwan: a prospective study. J Womens Health(2002). 2010;19(12):2247–51.

Goodman JH. Perinatal depression and infant mental health. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2019;33(3):217–24.

Austin MP. Antenatal screening and early intervention for “perinatal” distress, depression and anxiety: where to from here? Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004;7(1):1–6.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion no. 630. Screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1268–71.

Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, Doubeni CA, Epling JW Jr, Grossman DC, Force USPST, et al. Interventions to Prevent Perinatal Depression: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2019;321(6):580–7.

Nisar A, Yin J, Waqas A, Bai X, Wang D, Rahman A, Li X. Prevalence of perinatal depression and its determinants in Mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:1022–37.

Caropreso L, de Azevedo CT, Eltayebani M, Frey BN. Preeclampsia as a risk factor for postpartum depression and psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2020;23(4):493–505.

Howard LM, Oram S, Galley H, Trevillion K, Feder G. Domestic violence and perinatal mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001452.

Kalra H, Tran TD, Romero L, Chandra P, Fisher J. Prevalence and determinants of antenatal common mental disorders among women in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2021;24(1):29–53.

Schroeder SA, Morris CD. Confronting a neglected epidemic: tobacco cessation for persons with mental illnesses and substance abuse problems. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:297-314.291p following 314.

Biaggi A, Conroy S, Pawlby S, Pariante CM. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:62–77.

Unsal Atan S, Ozturk R, Gulec Satir D, Ildan Calim S, Karaoz Weller B, Amanak K, Saruhan A, Sirin A, Akercan F. Relation between mothers’ types of labor, birth interventions, birth experiences and postpartum depression: A multicentre follow-up study. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2018;18:13–8.

Acknowledgements

None

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Xiangdong Chen. Data curation: Kai Yang, Jing Wu. Formal analysis: Kai Yang, Jing Wu.Investigation: Kai Yang, Jing Wu. Writing: Kai Yang. Supervision: Xiangdong Chen. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable

Consent for publication

Not Applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, K., Wu, J. & Chen, X. Risk factors of perinatal depression in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 22, 63 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03684-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03684-3