Abstract

Background

Inborn errors of metabolism are often characterized by various psychiatric syndromes. Previous studies tend to classify psychiatric manifestations into clinical entities. Among inborn errors of metabolism, propionic acidemia (PA) is a rare inherited organic aciduria that leads to neurologic disabilities. Several studies in children with PA demonstrated that psychiatric disorders are associated to neurological symptoms. To our knowledge, no psychopathological description in adult with propionic acidemia is available.

Case presentation

We aimed to compare the case of a 53-year-old woman with PA, to the previous psychiatric descriptions in children with PA and in adults with other inborn errors of metabolism. Our patient presented a large variety of signs: functional neurologic disorders, borderline personality traits (emotional dyregulation, dissociative and alexithymic trends, obsessive-compulsive disorders), occurring in a context of neurodevelopmental disorder.

Conclusion

Clinical and paraclinical examinations are in favor of a mild mental retardation since childhood and disorders of behavior and personality without any definite psychiatric syndrome, as already described in other metabolic diseases (group 3). Nonetheless, further studies are needed to clarify the psychiatric alterations within adult patients with PA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Propionic Acidemia (PA) is a rare inherited (recessive autosomal) organic aciduria due to a propionyl-CoA carboxylase activity deficiency [4]. The disease is characterized by acute metabolic episodes, cardiac and renal failures and neurologic disorders [8]. Chronic neurologic and cognitive complications are frequent: movement disorders, spastic paresis, intellectual disability and strokes of basal ganglia [8]. There are two forms of the disorder: a severe form occurring in early life and associated with a high mortality rate and a chronic form associated with an evolution into neurologic disabilities [4].

Neurocognitive complications of organic acidurias are well described [13, 18,19,20]. However, literature about psychiatric symptoms occurring in organic acidurias is relatively scarce, less detailed and focuses mostly on children. Nonetheless, results showed that patients would be more susceptible to develop behavioral disorders such as self-damaging or self-regulating issues, anxious and avoidant behaviors, confirmed by parents [11]. Those behavioral signs are concordant with the higher prevalence of neurodevelopmental disorders in organic acidurias [18]. Concerning PA, the most frequent disorders are neurodevelopmental disorders from the Autism Spectrum ([5, 21]. A case series of 19 patients, aged between 2 and 25 years described 2 patients with typical autism, 2 patients with other autism spectrum disorders and 5 others with a broader autism phenotype (de la [3]). They also reported three patients with attention deficit symptoms and two with significant chronic anxiety symptoms. In addition, 13 of those 19 patients presented an intellectual disability. Rarely, psychotic signs are also reported: visual hallucinations [17] and rarely acute psychosis [6]. As compared to other organic acidurias, patients with PA would be more likely to develop psychiatric manifestations, such as attention deficit, or psychotic state [13, 20]. Unfortunately, those studies mostly concentrated on children or young adults. Hence, literature does not provide the psychiatric profile or evolution in adults suffering from Propionic Acidemia, neither other organic acidurias.

However, psychiatric manifestations have been described in adults suffering from other inborn errors of metabolism, and classified into three groups [16]. Group 1 included emergencies revealed by recurrent attacks of delusional confusion and concerned: urea cycle defects, homocysteine remethylation defects and porphyrias. Group 2 consisted in schizophrenia-like syndrome arising in young adults more often associated with catatonia, visual hallucinations and deterioration with treatments, and concerned: homocystinurias, Wilson disease, neurolipidosis (Niemann-Pick C, adrenoleukosdystrophy…). Group 3 included patients with mild mental retardation since childhood and disorders of behavior or personality with no definite psychiatric syndrome, and concerned: homocystinurias, cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis, nonketotic hyperglycinaemia, monoamine oxidase A deficiency, succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase defects, creatine transporter deficiency, and α- and β-mannosidosis. But no case of propionic acidemia was described among those groups, that included metabolic disorders with a pathophysiology distinct from organic acidurias.

Thus, we based our clinical evaluation of a 53-year-old woman with PA, on pedopsychiatric descriptions, available for PA and organic acidurias, to get an idea of the evolution of childhood disorders. We also aimed to compare the psychiatric evaluation, to the psychiatric manifestations described in other inborn errors of metabolism in adults.

Case presentation

The patient is a 53-year-old woman diagnosed with Propionic Acidemia (result of genetic mutation not available) at the age of 3 in the context of an acute metabolic episode revealing by a right-sided hemiplegia. She had a second acute episode revealed by a left-sided hemiparesis at 9 years old. Then she was well-controlled by a low-protein regimen.

She was followed by a neurologist for functional neurologic disorder appeared around the age of 50 years old, such as dystonia, dysphonia or abrupt loss of muscular tonus in legs. All those disorders improved during the follow-up: she had no dysphonia or dystonia anymore, but still presented rare episodes of muscular weakness. A psychiatric assessment was needed to complete the neurological evaluation.

Psychiatric examination

She had multiple follow-ups by child-psychiatrist for behavior disorders such as clastic crisis and multiple scarifications. She was hospitalized once around 25 years old for a suicidal attempt (self-phlebotomy). She also reported that psychiatrists suspected a bipolar disorder given cyclothymic signs and was treated by Aripiprazole. After 2 to 3 years, it was replaced by Venlafaxine.

She also reported traumatic events in her life: sexual abuse by a first husband, emotional and physical abuse by a second husband. We noted possible emotional neglect in childhood (communication issues with her parents).

She had been passionate by Asian culture (Korea and Japan) since this age of 5 years old and had correspondents with whom she shared her interest. She has had lots of pets and a reborn baby to bring herself some affection and to cope with a feeling of loneliness.

She stopped her psychiatric follow-up for at least 6 years but kept taking her antidepressant, Venlafaxine 225 mg/day and anxiolytic, Alprazolam when needed (medications were reconducted by her general practitioner).

On examination, she was mildly desinhibited and logorrheic, but her mood was globally stable. There was no argument for a hypomaniac, maniac neither depressed syndrome. She reported lots of bodily preoccupations during childhood and teenage with panic attacks (focused on nudity) that have progressively disappeared. Currently, she has been presenting an anxious apprehension of potential muscular weakness: she systematically went out with her wheelchair, although she has never needed it. She also has suffered from obsessive-compulsive disorders for several years. For medical appointments, she systematically established a very-detailed tables describing her symptoms (neurologic, psychiatric…) day per day for the last 6 months…The time dedicated to this tables had consequences on her sleep, her housekeeping and her personal hygiene.

She presented an emotional dysregulation with impulsivity, affective fluctuations and self-induced mutilations. The reborn baby seemed to satisfy an affective emptiness. She also had an alexithymia and dissociative symptoms with depersonalization and multiple episodes of dissociative amnesia in concordance with her traumatic history. During the current follow-up, she was once more victim of a sexual assault that has triggered a sudden episode of dissociative amnesia. She lost memory of the 4 past years and did not recognize her house, her doctor neither her dogs. She was completely detached when she told about the aggression. This dissociative episode has spontaneously recovered after 1 week.

Autistic symptoms were not clinically marked: we only found difficulties for understand implicit sense and some sensorial intolerance. She had no psychotic sign: no hallucination, no delusion or disorganized thoughts. We did not find symptoms of eating-behavior disorder.

Psychometric evaluation

Table 1.

Neuropsychological evaluation

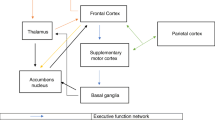

The patient presented a mild global intellectual disability. On memory functions she had deficiencies in short-term memory and working memory, but episodic memory was intact. Executive functions were globally preserved. She also had difficulty in planification and a longer processing speed (Table 2).

Brain magnetic resonance imaging

In front of the presence of motor dysfunction and cognitive deficiency, a brain MRI was performed. Furthermore, given the obsessive-compulsive syndrome, we looked for possible attempts of basal ganglia due to propionic acidemia. Indeed in less than 10% of cases, obsessive-compulsive disorders are secondary to basal ganglia pathology [9, 10]. Here, MRI did not highlight significant abnormality (Fig. 1).

Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the patient, revealing absence of abnormalities especially within basal ganglia. A Axial T2 sequencing centered on basal ganglia; B Axial FLAIR sequencing centered on basal ganglia; C Axial T2* centered on basal ganglia; D Axial T1 sequencing centered on basal ganglia; E Sagittal FLAIR sequencing centered on midbrain; F Axial T2 sequencing centered on cerebellum)

Discussion and conclusion

Our objective was to compare the psychiatric evaluation of an adult with propionic acidemia to other organic acidurias and inborn errors of metabolism and to get an idea of the psychopathological evolution of psychiatric childhood disorders of propionic acidemia.

In our patient, psychiatric and neuropsychological examinations found a mild mental retardation associated with features evoking a “borderline-like” personality disorder with emotional dysregulation (that had led to a temporary suspicion of bipolar disorder), dissociative and alexithymic symptoms and self-induced injuries. Dissociative and alexithymic symptoms were clinically patent and potentially explained her functional neurological signs, even though psychometric scores rated below the certitude threshold (> 61 for TAS and > 30 for DES) [2, 7]. She also had a mild Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, confirmed by Y-BOCS. In resume, the patient suffered from several psychiatric symptoms from different syndroms, associated with behavioral disorders and mild intellectual disability. All those results are in favor to a psychiatric profile corresponding to the group 3 described previously [16]. However, given the lack of publication on psychiatric manifestations in adult with propionic acidemia, we do not know whether our case is representative or not. Secondly, the psychiatric manifestations of our patient could be due to her traumatic history and not to her metabolic disorder. Indeed, borderline personality traits and dissociative symptoms are associated with sexual and physical abuse and emotional neglect (de Aquino [1]). In addition, one could suppose that propionic acidemia is associated with an emotional dysregulation, as suggested by previous literature in children and young adults with PA or others organic acidurias [11, 13, 18]. This issue of self-regulation could lead to an hyperreactivity to traumatic events. This hypothesis might explain the high arousal of dissociative amnesia presented by our patient. But further evaluations of adult with propionic acidemia need to be performed to get a more precise representation of the psychiatric profile and to add in the classification developed by Sedel et al. As a result, different metabolic diseases with miscellaneous pathophysiology could lead to the same psychiatric phenotype. One could assume, either that the psychiatric symptoms occurring in metabolic disorders are not specific to it but are rather a comorbidity of a chronic condition; or that different metabolic pathways are involved in the same neurotransmitter regulation [15].

Regarding the psychopathological evolution, anamnestic investigations did not find relevant arguments for a complete autism but the patient presented a corporal anxiety in childhood (that were described in the serie of cases (de la [3]), a difficulty to understand implicit and sensorial intolerances. Moreover, she developed an obsessive-compulsive disorder that is not due to basal ganglia lesions. We can then suppose that it could be an equivalent or an evolution of rituals and stereotypies of an autism spectrum disorder. But since we did not have access to the pedopsychiatric data of our patient, this hypothesis could not be verified. Further clinical investigations of adult with propionic acidemia could help to draw a psychopathological evolution from childhood to adulthood.

Finally, given the risk of basal ganglia strokes in propionic acidemia, a brain MRI should be systematically prescribed in front of Obsessive-compulsive disorders that can be secondary to basal ganglia dysfunction [9, 10, 14].

This clinical observation highlights the importance of a psychiatric assessment in adult patients with metabolic disorders, whereas literature is relatively scarce about this topic. Yet, metabolic disorders are known to be a cause of secondary psychiatric disorders [12, 15], mental disorders are frequent comorbidities of metabolic diseases, and could be useful in research as a comprehensive model for primary psychiatric disorders [15].

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during this study concerned confidential data and are available only from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

10 January 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03656-7

Abbreviations

- PA:

-

Propionic Acidemia

- mg:

-

Milligrams

- MRI:

-

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- TAS:

-

Toronto Alexithymia Scale

- DES:

-

Dissociative Experience Scale

- GAD:

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

- Y-BOCS:

-

Yale-Brown Obsession-compulsion scale

References

de Aquino Ferreira LF, Pereira FHQ, Benevides AMLN, Melo MCA. Borderline personality disorder and sexual abuse: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2018;262:70–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.01.043.

Bagby RM, Parker JD, Taylor GJ. The twenty-item Toronto alexithymia scale--I. item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38(1):23–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(94)90005-1.

de la Dejean BC, Barbier V, Roda C, Brassier A, Arnoux J-B, Valayannopoulos V, et al. Autism Spectrum disorders in propionic Acidemia patients. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2018;41(4):623–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10545-017-0070-2.

Baumgartner MR, Hörster F, Dionisi-Vici C, Haliloglu G, Karall D, Chapman KA, et al. Proposed guidelines for the diagnosis and Management of Methylmalonic and Propionic Acidemia. Orphan J Rare Dis. 2014;9(September). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-014-0130-8.

Cotrina ML, Ferreiras S, Schneider P. High prevalence of self-reported autism Spectrum disorder in the propionic Acidemia registry. JIMD Rep. 2020;51(1):70–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmd2.12083.

Dejean de la Bâtie C, Barbier V, Valayannopoulos V, Touati G, Maltret A, Brassier A, et al. Acute psychosis in propionic Acidemia: 2 case reports. J Child Neurol. 2014;29(2):274–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073813508812.

Dubester KA, Braun BG. Psychometric properties of the dissociative experiences scale. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183(4):231–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199504000-00008.

Fraser JL, Venditti CP. Methylmalonic and propionic Acidemias: clinical management update. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2016;28(6):682–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000422.

Graybiel AM, Rauch SL. Toward a neurobiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuron. 2000;28(2):343–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00113-6.

Grimshaw L. Obsessional disorder and neurological illness. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1964;27(3):229–31.

Jamiolkowski D, Kölker S, Glahn EM, Barić I, Zeman J, Baumgartner MR, et al. Behavioural and emotional problems, intellectual impairment and health-related quality of life in patients with organic Acidurias and urea cycle disorders. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2016;39(2):231–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10545-015-9887-8.

Keshavan MS, Kaneko Y. Secondary psychoses: an update. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):4–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20001.

Nizon M, Ottolenghi C, Valayannopoulos V, Arnoux J-B, Barbier V, Habarou F, et al. Long-term neurological outcome of a cohort of 80 patients with classical organic Acidurias. Orphan J Rare Dis. 2013;8(September):148. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-8-148.

Rapoport JL. Obsessive compulsive disorder and basal ganglia dysfunction. Psychol Med. 1990;20(3):465–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700016962.

Rukavishnikov G, Kasyanov E, Zhilyaeva T, Neznanov N, Mazo G. Inherited metabolic diseases as a multisystem model of mental disorders research. J Inborn Errors Metab Screen. 2021;9:e20200015. https://doi.org/10.1590/2326-4594-jiems-2020-0015.

Sedel F, Baumann N, Turpin J-C, Lyon-Caen O, Saudubray J-M, Cohen D. Psychiatric manifestations revealing inborn errors of metabolism in adolescents and adults. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007;30(5):631–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10545-007-0661-4.

Shuaib T, Al-Hashmi N, Ghaziuddin M, Megdad E, Abebe D, Al-Saif A, et al. Propionic Acidemia associated with visual hallucinations. J Child Neurol. 2012;27(6):799–803. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073811426929.

Sindgikar SP, Shenoy KD, Kamath N, Shenoy R. Audit of organic Acidurias from a single Centre: clinical and metabolic profile at presentation with long term outcome. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(9):SC11–14. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2017/28793.10632.

Tuncel AT, Boy N, Morath MA, Hörster F, Mütze U, Kölker S. Organic Acidurias in adults: late complications and management. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2018;41(5):765–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10545-017-0135-2.

Wajner M. Neurological manifestations of organic Acidurias. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(5):253–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-019-0161-9.

Witters P, Debbold E, Crivelly K, Kerckhove KV, Corthouts K, Debbold B, et al. Autism in patients with propionic Acidemia. Mol Genet Metab. 2016;119(4):317–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymgme.2016.10.009.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

PHRC EDUQ CPNE paid for the language editing service, and contributed in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AT performed the psychiatric assessment, acquisition of clinical data and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. SFK performed neurological evaluation, collected clinical data and image, and critical revision of the manuscript. CH performed critical revision and analysis of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Patient gave a written informed consent scientific use of her medical data after anonymization.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-In-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests for this case report.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: funding note has been added.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tarrada, A., Frismand-Kryloff, S. & Hingray, C. Functional neurologic disorders in an adult with propionic acidemia: a case report. BMC Psychiatry 21, 587 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03596-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03596-2