Abstract

Background

Little is known about depression in middle-aged and older Canadians and how it is affected by health determinants, particularly immigrant status. This study examined depression and socio-economic, health, immigration and nutrition-related factors in older adults.

Methods

Using weighted comprehensive cohort data from the baseline Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (n = 27,162) of adults aged 45–85, gender-specific binary logistic regression was conducted with the cross-sectional data using the following variables: 1) Depression (outcome) measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression (CESD-10) rating scale; 2) Immigration status: native-born, recent and mid-term (< 20 years), and long-term immigrants (≥20 years); and 3) covariates: socioeconomic status, physical health (e.g., multi-morbidity), health behavior (e.g., substance use), over-nutrition (e.g., anthropometrics), under-nutrition (e.g., nutrition risk), and dietary intake.

Results

The sample respondents were mainly Canadian-born (82.6%), women (50.6%), 56–65 years (58.9%), earning between C$50,000–99,999 (33.2%), and in a relationship (69.4%). When compared to Canadian-born residents, recent, mid-term (< 20 years), and longer-term (≥ 20 years) immigrant women were more likely to report depression and this relationship was robust to adjustments for 32 covariates (adjusted ORs = 1.19, 2.54, respectively, p < 0.001). For women, not completing secondary school (OR = 1.23, p < 0.05), stage 1 hypertension (OR = 1.31, p < 0.001), chronic pain (OR = 1.79, p < 0.001), low fruit/vegetable intakes (OR = 1.33, p < 0.05), and fruit juice (OR = 1.80, p < 0.001), chocolate (ORs = 1.15–1.66, p’s < 0.05), or salty snack (OR = 1.19, p < 0.05) consumption were associated with depression. For all participants, lower grip strength (OR = 1.25, p < 0.001) and high nutritional risk (OR = 2.24, p < 0.001) were associated with depression. For men, being in a relationship (OR = 0.62, p < 0.001), completing post-secondary education (OR = 0.82, p < 0.05), higher fat (ORs = 0.67–83, p’s < 0.05) and omega-3 egg intake (OR = 0.86, p < 0.05) as well as moderate intakes of fruits/vegetables and calcium/high vitamin D sources (ORs = 0.71–0.743, p’s < 0.05) predicted a lower likelihood of depression. For men, chronic conditions (ORs = 1.36–3.65, p’s < 0.001), chronic pain (OR = 1.86, p < 0.001), smoking (OR = 1.17, p < 0.001), or chocolate consumption (ORs = 1.14–1.72, p’s < 0.05) predicted a higher likelihood of depression.

Conclusions

The odds of developing depression were highest among immigrant women. Depression in middle-aged and older adults is also associated with socioeconomic, physical, and nutritional factors and the relationships differ by sex. These results provide insights for mental health interventions specific to adults aged 45–85.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

On a global basis, depressive disorders are estimated to impact one in every 23 people [1]. Major depressive disorder is the second leading cause of disability and accounts for one-twelfth of all years lost to disability world-wide [2]. While the etiology of the condition is multi-factorial, a particular concern is depression that occurs in adulthood as it has been associated with chronic disease incidence and complications, high utilization of health services, nursing home admission, suicide, dementia, and shortened life expectancy [3,4,5,6].

Theoretical and empirical evidence indicates that various social determinants are associated with depression. Higher prevalence or incidence of major depression tends to occur in women [7] as well as older adults, those who are not married, and those with lower incomes [8]. The association between depression and education level seems to interact with working status. Longitudinal research indicates that among those free from depression at baseline, individuals with a secondary school education or less have a much higher likelihood of developing a major depressive episode (MDE) than more educated working respondents. Among the unemployed, higher risk of major depression was found among those with a higher level of education [9].

Nutrient intake, health behaviors and health status are also related to depression. Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies that have compared intakes of grains, dairy, and lean meats or ``traditional`` diet patterns (e.g., Mediterranean, Japanese, Norwegian) and “unhealthy” diets have shown that increased adherence to low quality diets (e.g., more processed foods, nutrient poor) are less protective against depression diagnosis and symptoms [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Longitudinal investigations indicate that health behaviors such as smoking and physical activity have a larger impact on depression than diet [18]. Additional risk factors for depression include substance use, a family history of psychiatric disorders [19, 20], presence of pain [21] and co-morbidities [22], and, for women in particular, high visceral adiposity [23].

There has been limited exploration of these relationships among marginalized groups such as immigrants. Globally, substantial regional variation in the occurrence of depression exists [1] and levels among immigrants may be closer to the average of individuals in their country of origin than their receiving country. For example, Asian immigrants in Canada experience a much lower prevalence of depression than immigrants from Europe, the USA or Canada [24], which is consistent with the relative level of depression in the source countries. Among Canadian immigrants, cross-sectional studies report lower levels of depressive symptoms compared to native born Canadians [25,26,27,28]. A representative longitudinal study of new immigrants showed a steep increase over time in self-reported sadness and/or loneliness from 5.1% in the first 6 months in Canada to 30% after 2 years, a level which persisted even 4 years after arrival [29]. Several factors may confound the relationship between immigrant status and depression such as age [28, 30, 31], gender, marital status and education. Men, as well as those who are married, and those who have a higher education are less likely to experience depression [27, 32]. Other contributors to depression include chronic physical or mental health conditions, chronic pain [33, 34], substance use [35], and obesity [36]. Although recent immigrants are less likely to be overweight and obese when compared to native-born residents, the prevalence of obesity among longer-term immigrants converges with that of the native-born population [37]. Little is known about how obesity affects the level of depression among immigrants [38].

There are several reasons why the migration, integration and settlement process could contribute to immigrants’ vulnerability to mental ill health [39]. Immigrating individuals may experience substantial stress associated with settling in a new country due to insufficient income [40], language barriers [41, 42], discrimination, cultural adaptation [43], reduced social support networks [44, 45], and a lack of recognition of their education and work experiences in the receiving countries [46]. These challenges may result in downward social mobility and concomitantly a higher risk of mental health problems, especially for immigrant women [46,47,48]. The impact of immigration on mental health depends on both individual and societal factors such as language proficiency and health care access in the host country [49, 50]. Despite the stress of migration, on average, immigrants are in better health than their non-immigrant peers in the receiving country [51,52,53,54,55,56], particularly after socioeconomic status is taken into account [53, 57]. The health advantage of immigrants, also known as the healthy migrant effect, has been reported among select immigrant populations in the US [58, 59], Australia [60], and Canada [61]. Such favorable effects may be due to processes of positive selection for individuals without chronic or acute health problems [62] and reverse migration (i.e., the return of immigrants to their home countries once they become ill) which may falsely increase the reporting of good health among immigrants in their receiving countries [54, 59, 62].

Culture-specific dietary habits and health behaviors may contribute to good health in the early years for immigrants, however, their diets may change significantly over time resulting from negative acculturation [63]. A US study found that although newer immigrants were at a lower risk of carrying excess weight, the prevalence of obesity among American immigrants living more than 15 years was similar to that of the US-born population [64]. For Canadian immigrants, the acculturation process may be conducive to healthy dietary habits by reducing nutritional deficiencies in calcium, iron and vitamin D, but it may also contribute to poor health related to higher intakes of fat and sodium [38]. Studies of smoking behavior have indicated that in some immigrant subpopulations, particularly women, smoking rates increase after immigration [65, 66]. Whether the healthy migrant effect is maintained after decades in the host country is not clearly established. Some studies have indicated that immigrants’ health advantage appears to deteriorate over time [67,68,69] and may converge with native-born population levels [52], while other investigations reported that over time immigrants continue to maintain better health than native-born populations [70].

Promoting excellent mental health among middle-aged and older Canadians, both immigrants and non-immigrants, is an important priority among policymakers, health practitioners and researchers [38, 71, 72]. However, there is inadequate information on the relationship between depression in this population and immigration status, socioeconomic status, physical health (e.g., multi-morbidity), health behaviors (e.g., substance use, physical activity), over-nutrition (e.g., anthropometrics, disease risk), poor nutrition status (e.g., handgrip strength, nutrition screen scores, body composition, anemia screen), and dietary intake.

To help address these knowledge gaps, the current study utilized baseline data from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. The focus of the analysis was to explore the following research questions/objectives in middle-aged and older adults:

-

1.

Is immigrant status associated with depression among Canadian women and/or Canadian men aged 45 to 85 years?

-

2.

To what extent does adjustment for a wide range of demographic, social, economic, and health-related characteristics attenuate the association between immigrant status and depression?

-

3.

Is there an association between dietary intake and depression after controlling for immigration status?

-

4.

What other factors are associated with depression among Canadians aged 45 to 85 years after controlling for immigration status?

Methods

Study population

The sample of this study included the baseline comprehensive set of participants (n = 30,097) of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). The CLSA is a prospective study that includes biological, medical, psychological, social, lifestyle, and economic measures of Canadians aged 45 to 85 years old who will be followed for 20 years [73]. Participants in the comprehensive sample were administered in-home interviews and a wide range of physical assessment data was collected from them at dedicated data collection sites [74]. Those who did not have their anthropometrics assessed were excluded (n = 2935), yielding a final sample size of 27,162. Further details about the study protocol can be found at: https://www.clsa-elcv.ca.

Measures

Dependent variable

Depression

The outcome, depression, was measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression (CESD-10) rating scale. The CESD-10 contains Likert scale questions that assess depressive symptoms in the past week. It includes 10 questions: three about depressed affect, five about somatic symptoms, and two about positive affect (e.g., hopefulness for the future). Each question has four possible response options that range from “all of the time” (5–7 days; score of 3) to “rarely or none of the time” (score of 0). Total scores range between 0 to 30 and the cut-off score of ≥10 [75] was used to screen for depression.

Independent variable

Immigration status

The primary relationships of investigative interest were the differences between foreign-born immigrants of Canada and native-born Canadians in relation to depression. Three categories of participants were compared: recent and mid-term immigrants (< 20 years), longer-term immigrants (≥20 years), and native-born Canadians.

Covariates

Demographic, socioeconomic, and health-related variables that could attenuate the relationship between depression and immigration status were also examined in the analysis.

Demographic, social and economic characteristics

Demographic measures included age (45–55, 56–65, 66–75, 76–85 years), sex (men, women), and relationship status (single/ married, living with a partner, or common-law/widowed, divorced or separated). Socioeconomic status measures included level of education (less than secondary school graduation, high school graduate or with some post-secondary education, post-secondary degree or diploma, non-response) and household income, defined as the best estimate of the total gross household income received by all household members in the past 12 months (<$20,000, $20,000 to <$50,000, $50,000 to <$100,000, $100,000 to <$150,000, ≥$150,000, non-response).

Physical health measures

Multi-morbidity measures were based on reported diagnosis by a doctor of at least one of 18 chronic conditions (diabetes, borderline diabetes or blood sugar, heart disease or congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease or poor circulation in limbs, dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, migraine headaches, intestinal or stomach ulcers, bowel disorders such as Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, or irritable bowel syndrome, macular degeneration, anxiety disorder, mood disorder, back problems (excluding fibromyalgia and arthritis), kidney disease or kidney failure, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis in the hands, hip and/or knee, and cancer). The number of conditions was summed and the total values were categorized as no health condition, one health condition, two health conditions and more than two health conditions. Chronic pain was a derived variable that was based on two questions about whether or not respondents were usually free from discomfort (yes/no) and the number of activities that their pain or discomfort prevented them from doing (none, few, some, most). Responses to these queries were coded as either “free from pain” or “a few, some or most activities prevented by pain”. Average blood pressure results were based on the average of five readings. With reference to established guidelines [76], the average blood pressure readings were categorized into five types: normal (systolic < 120 mmHg and diastolic < 80 mmHg), elevated hypertension (systolic 120–129 mmHg and diastolic < 80 mmHg), stage one hypertension (systolic 130–139 mmHg or diastolic 80–89 mmHg), stage two hypertension (systolic ≥140 mmHg or diastolic ≥90 mmHg), and currently taking anti-hypertensive medication.

Health behavior measures

Smoking status was a binary variable that was based on responses to a question pertaining to whether participants ever smoked at least 100 tobacco cigarettes in their lifetime (yes/no). Drinking behavior was classified as non-binge drinker, occasional binge drinking, and regular binge drinking. Binge drinking behavior was defined as men who had five or more drinks or women who had four or more drinks on the same occasion. The variable was categorized as regular (at least once a month in the past 12 months) [77], occasional (less than once a month but at least once in the past 12 months), and non-binge drinkers (never in the past year). Physical activity was based on a question that asked about frequency in engagement of light sports or recreational activities (e.g., bowling, golf with a cart, shuffleboard, badminton, fishing) in the previous 7 days (never or seldom, sometimes or often, non-response).

Nutrition status indicators

There were five body composition-related measures included in the analysis: 1) body mass index (BMI) categorized as obese (≥ 30 kg/m2), underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), healthy weight (18.5 to 24.99 kg/m2), overweight (25 to 29.99 kg/m2); 2) waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) dichotomized into high risk and low risk based on the cut-off of 0.85 for women and 0.90 for men [78]; 3) waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) where values above 0.50 suggest an increased risk [79]; 4) body fat percent based on dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) and subdivided into five categories (< 26%, 26–31%, 31–36%, 36–41%, 41–59%); and 5) a composite measure of disease risk based on the standard aforementioned classifications of BMI and WHR (least risk, increased risk, high risk, very high risk) [80]. Five measures of poor nutrition status: 1) handgrip strength (HGS) measured by the Tracker Freedom wireless grip dynamometer. Based on cut-off values of 19.2 kgf (kilogram force) for women 45 years+ and 37.9 kgf for men between 45 and 64 years and 30.2 kgf for men 65 years+ [81], three categories were included: under-nutrition, no under-nutrition, or not assessed; 2) nutritional risk derived from responses to a standardized assessment tool, namely, Abbreviated Seniors in the Community Risk Evaluation for Eating and Nutrition II (AB SCREEN™ II).

Total scores were grouped into high risk (< 38), low risk (≥38), and not assessed; 3) sarcopenia based on skeletal muscle mass measured using DEXA and a derived skeletal muscle index that was derived using European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People’s screening algorithms [82]. Sex-specific quintile points were applied with the 20 percentile used as the cut-off score to classify respondents as having sarcopenia or not [83]; 4) bone mineral densities (BMDs) measured by DEXA that yielded T-score values: osteoporosis (T-score ≤ − 2.5), osteopenia (T-score − 1 to − 2.5), and normal bone density (T-score > − 1); 5) anemia screen based on measures of haemoglobin with the cut-off values of ≤119 g/L for women and ≤ 129 g/L for men [84]. A third category for those who did not consent to blood work was included.

Dietary intake measures

Dietary intake assessments were measured using a semi-quantitative 36-item Short Diet Questionnaire that evaluated habitual consumption frequencies of selected food groups (e.g., fruits and vegetables) and foods that are sources of select nutrients of interest (e.g., fats, calcium, vitamin D) as standard portions per day [85]. Fiber intake was based on consumption of high fiber breakfast cereals, whole wheat, bran, multigrain, and rye breads. Pulses and nuts included legumes (beans, peas, lentils), nuts, seeds and peanut butter. Fat sources were based on total consumption of the following food items: French fries or pan-fried potatoes, poutine; butter or regular margarine on bread or on cooked vegetables only; regular vinaigrettes, salad dressings, mayonnaise, homemade or commercial dips; beef, pork (ground, hamburgers, roast beef, steak, cubed); other meats (veal, lamb, game); patés, cretons, terrines; sauces and gravies (brown, white); sausages, hot dogs, ham, smoked meat, bacon; all egg dishes except omega 3 eggs (eggs, omelette, quiche); chicken, turkey. Omega 3 fatty acid intakes were based on consumption of fish and consumption of omega 3 eggs. Daily average intake of fruits and vegetables included fresh, frozen, or canned fruits, green salad, potatoes, carrots and other vegetables. Calcium-containing food sources with high vitamin D content were based on average daily intakes of calcium-fortified milk (35% more calcium), whole and skimmed milk (3.25, 2, 1% milk fat), low-fat and regular cheeses; milk-based desserts; calcium-fortified beverages and juices. Calcium-containing food sources with low vitamin D content included yogurt (low-fat and regular) and calcium-fortified foods. Other food groups that were assessed included 100% pure fruit juices (e.g. orange, grapefruit or tomato), salty snacks (e.g. regular chips, crackers), pastries (e.g. cakes, pies, doughnuts, pastries, cookies, muffins), and chocolate bars.

For variables where there were missing values, the Missing Indicator Method was applied [86]. Missing values included responses such as “not answered” or “refused.” It also included clinical variables that were “not assessed” and measures where consent was not provided (“no consent for sample”).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were completed using SPSS Version 22 [87]. As a modification of the model-based approach, normalized trimmed inflation weights were applied to provide estimates that are representative of the national population. The standardized weights were derived by dividing the trimmed inflation weight of each unit used in the analysis by the (unweighted) average of the survey weights of all the analyzed units.

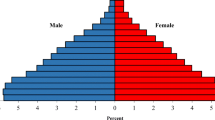

Descriptive information and inferential statistics were generated by Chi-square tests using weighted means. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) were derived from binary logistic regression to examine associations between immigrant status and depression while adjusting for the covariates. Six stepwise models were analyzed by entering demographic and socioeconomic variables (Model 1), physical health measures (Model 2), health behavior variables (Model 3), over-nutrition and poor nutrition status indicators (Models 4 and 5), and dietary intake measures (Model 6) respectively. The final model was adjusted for all aforementioned variables (Model 7). The interaction variable of sex by immigration status was significant and therefore separate logistic regression analyses were conducted for women and men.

Results

Description of sample

Table 1 presents details about the proportion of men and women in the sample who were experiencing depressive symptoms. Overall, the sample mainly consisted of Canadian born residents (n = 22,423, 82.6%), 56–65 years (n = 16,008, 58.9%), earning between C$50,000–$99,999 annually (n = 9031, 33.2%), in a married or common-law relationship (n = 18,859, 69.4%), who had earned a post-secondary diploma or degree (n = 21,115, 77.7%). Among the demographic, social, and economic factors, significant associations were found for men and women by income, relationship status, and education level categories (p’s < 0.001). For the age, significant association was only found among men (p < 0.001).

In terms of health-related characteristics, the majority had at least one health condition (n = 22,297, 82.1%), some type of hypertension or taking anti-hypertensive medication (n = 17,285, 63.6%), and reported having no chronic pain (n = 20,569, 75.7%). Most respondents did not drink excess alcohol (n = 17,552, 64.6%) and did limited physical activity (n = 23,264, 85.6%). There were significant associations between all physical health and health behavior characteristics (p’s < 0.05–0.001). For nutrition status indicators, there tended to be a higher proportion of the sample having characteristics that were indicative of over-nutrition. All body composition measures indicated that the majority tended to have excess weight based on BMI measures (n = 18,893, 69.7%), high visceral adiposity based on WHR (n = 17,898, 65.9%), high body fat percent (n = 16,752, 61.7%), and elevated disease risk based on BMI and WHR measures (n = 19,198, 70.8%). There were significant associations for all over-nutrition indications (p’s < 0.05–0.001). While there were significant associations found for indicators of poor nutrition that included grip strength (p < 0.001) and nutritional risk (p < 0.001), most of the sample did not have the characteristics that would be indicative of under-nutrition. For men,

however, there was a high proportion who had sarcopenia (n = 11,282, 41.5% of the total sample) (χ2(1) = 57.4, p < 0.001). For men, significant association were also found for the anemia screen (χ2(2) = 15.6, p < 0.001) measurement, however, most of the men screened negative (n = 10,448, 38.5% of the total sample).

For both men and women, most of the 12 dietary intake measures were significantly associated with depression. Overall, the sample tended to have low intakes of fiber (≤2 servings/day; n = 21,617, 79.6%), however there was only a significant association found for women (χ2 = 21.8 (3), p < 0.001). Most of the sample also had low intakes of pulses and nuts (≤1 serving/day; n = 15,027, 55.3%) as well as fruits and vegetables (≤4 servings/day; n = 17,193, 63.3%) and there were significant associations found for both of these dietary intake measures (p’s < 0.001). For the intakes of calcium containing foods, most of the sample consumed low amounts of those with high vitamin D content (≤2 servings/day; n = 18,345, 67.5%), and a significant association was only found for men (χ2(3) = 19.4, p < 0.001). For sources with low vitamin D content, most of the sample consumed some level of these (n = 22,194, 81.7%) with significant associations indicated (p’s < 0.001). For dietary sources of the omega-3 fatty acids, most consumed fish (n = 24,891, 91.6%, p’s < 0.001); few consumed omega-3 eggs (n = 20,058, 73.8%) which only showed significant association for women (χ2(1) = 9.6, p < 0.05). About half of the sample on average consumed four or more fat sources (n = 13,543, 49.9%). There was a significant association between number of fat sources consumed daily and depression among men (χ2(3) = 18.1, p < 0.001), but not among women. More than two-thirds of the sample’s average daily intakes of pure fruit juice, salty snacks, and pastries were less than once daily and of these pure fruit juice (χ2(3) = 12.6, p < 0.05) and pastries (χ2 (2) = 7.75, p < 0.05) showed significant association for women. On a weekly basis, most of the sample on average consumed less than two-thirds of a chocolate bar (n = 25,938, 95.5%) and significant association was indicated (p’s < 0.001). The immigrant sample was categorized according to years since immigration with those who had lived in Canada less than 20 years considered as recent and mid-term immigrants. Those who had resided in Canada 20 or more years were considered as long-term immigrants. On average, the recent and mid-term immigrant group had resided in Canada almost 12 years (Mean = 11.8, SD ± 4.6). The average years since immigration for females (Mean = 12.3, SD ± 4.5) was slightly higher than males (Mean = 11.5, SD ± 4.7). Mean years since immigration for the long-term group was 47 years (Mean = 47.1, SD ± 12.1) with the average being slightly higher for males (Mean = 47.3, SD ± 12.1) compared to females (Mean = 46.9, SD ± 12.2).

Bivariate and multivariable analysis

Objective 1. Is immigrant status associated with depression among Canadian women and/or Canadian men aged 45 to 85?

There was a significantly higher proportion of immigrant women with depression compared to Canadian-born women (18.8%, 28.9% versus 17.1%, χ2 (2) =31.8, p < 0.001) (Please see Table 1). Immigration status and depression were not associated among men (χ2(2) = 2.74, p = 0.26).

Objective 2. To what extent does adjustment for a wide range of demographic, social, economic, and health-related characteristics attenuate the association between immigrant status and depression?

As shown in Fig. 1a and b, among women, after adjusting for demographic, social, and economic characteristics, the odds of depression among recent and mid-term immigrant women ranged from 2.03 to 2.54 in comparison to Canadian-born respondents. The odds ratios remained consistently above 2.00 across all models that adjusted for most of the known and/or postulated determinants of depression. The odds of depression among long-term immigrant women ranged from 1.12 (95% CI 0.99–1.27) controlling for demographic, social, and economic factors (Model 1), to 1.19 (95% CI 1.04–1.35) after full adjustments. As shown in Fig. 2a and b, among men, neither recent, mid-term or longer-term immigration status was associated with depression in any of the models.

In sum, the adjusted odds ratios across all models (Figs. 1 and 2) showed that for recent and mid-term immigrant women the likelihood of depression was at least two times that of Canadian-born women. This association between immigrant status and depression among recent and mid-term immigrant women was consistently robust and not attenuated by a wide range of social, economic, and health-related determinants. Furthermore, although the OR for depression and long-term immigrant women was not significant in Model 1, after social, economic, and health-related factors were adjusted, immigrant women had a higher likelihood of depression compared to native-born Canadian women.

Objective 3. Is there an association between dietary intakes and depression after controlling for immigration status?

There were many important differences between men and women when the associations between dietary intakes and depression were considered after controlling for immigration status (Please see Table 2). Men who on average consumed higher levels of fat sources (≥4 sources/day; ORs = 0.67–69, p’s < 0.05), lower levels of omega 3 eggs (OR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.76–0.98, p < 0.05), and between 3 and 6 daily servings of fruits and vegetables/day (ORs = 0.71–0.74, p’s < 0.05) had a lower likelihood of depression. Men who consumed any chocolate bars on a weekly basis had an increased likelihood of depression (ORs = 1.14–1.72, p’s < 0.05). For women, lower levels of fruit and vegetable intakes (< 2 servings/day, OR = 1.33, 95% CI 1.09–1.64, p < 0.05), higher intakes of pure fruit juice (> 1 serving/day, OR = 1.80, 95% CI 1.24–2.59, p < 0.05), average daily intakes of 1 or less of salty snacks (OR = 1.19, 95% CI 1.04–1.36, p < 0.05), and any chocolate bar consumption (ORs = 1.15–1.66, p’s < 0.05) were significantly associated with depression.

Objective 4. What other factors are associated with depression among Canadians aged 45 to 85 after controlling for immigration status?

The odds of depression for demographic, social, and economic variables differed by gender (Please see Table 2). For men only, those who were married, living with a partner or in a common-law relationship (OR = 0.62, 95% CI 0.52–0.75, p < 0.001) or who had a post-secondary degree or diploma (OR = 0.82, 95% CI 0.70–0.95, p < 0.05) had a lower likelihood of depression. For both men and women who were 55 years or older, there was a lower likelihood of depression (ORs 0.40–0.79, p’s < 0.001), and an inverse relationship between depression as incomes increased (p’s < 0.001).

Associations between depression and different health determinants such as physical health and health behaviors also varied between men and women. Men who reported having at least one health condition (ORs = 1.36–3.65, p’s < 0.001), having chronic pain (OR = 1.86, 95% CI 1.63–2.13, p < 0.001), or smoking (OR = 1.17, 95% CI 1.04–1.32, p < 0.001) had a higher likelihood of reporting depression. Women who had least one health condition (ORs = 1.27–3.01, p’s < .05), chronic pain (OR = 1.79 95% CI 1.60–1.99, p < 0.001), or stage 1 hypertension (OR = 1.31, 95% CI 1.13–1.51, p < 0.001) had a higher likelihood of reporting depression.

For nutrition status indicators, men and women tended to have the same factors associated with depression. These included grip strength as a measure of under-nutrition (ORs = 1.25, p’s < 0.001) and high nutritional risk (ORs = 2.24, p’s < 0.001). For women not assessed for nutritional risk (OR = 1.97, p < 0.05), the likelihood of depression was higher.

Depression in the above analyses was based solely upon the individual’s current CES-D scores. Therefore, those with a score below the cutpoint were classified as ‘not depressed’ even if they were taking prescribed antidepressants and/or had been diagnosed with depression. We conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we reclassified these individuals into the ‘depressed’ category. When we re-analyzed the data with this new outcome variable, the findings were similar to the original with respect to relationship between the immigrant variable and depression.

Discussion

This study examined depression in a nationally representative sample of Canadians in middle and late adulthood and found significant effect modification between immigrant status and sex. For women, depression was associated with immigrant status, less than secondary school graduation education, stage 1 hypertension, chronic pain, low intakes of fruits and vegetables, consumption of pure fruit juice, and intakes of salty snacks. For men, being in a relationship and having a post-secondary degree or diploma appeared to be protective against depression. Conversely, men were more likely to experience depression if they smoked, consumed higher levels of fat, or lower levels of omega 3 eggs, fruits and vegetables, or calcium sources with high vitamin D content. For both men and women, depression was associated with having at least one health condition, pain, poor nutritional status, and consuming chocolate bars.

Objective 1. Is immigrant status associated with depression among Canadian women and/or Canadian men aged 45 to 85?

Among women, immigrant status was associated with depression. This finding is consistent with longitudinal investigations of new immigrants which show increases in reported sadness and loneliness [29], but is inconsistent with cross-sectional studies that report lower levels of depressive symptoms when compared to native born Canadians [25,26,27,28]. Differences in the results may be attributed to the older age of this sample (45–85 years old) and how depression was measured and what potential confounders were accounted for. The immigrant women in this study may have reported depression as a result of the substantial stress associated with settling in a new country such as having insufficient income [40], overcoming language barriers [41, 42], facing discrimination, adapting to a different culture [43], reduced social support networks [44], and having their education and work experiences unrecognized [45].

Objective 2. To what extent does adjustment for a wide range of demographic, social, economic, and health-related characteristics attenuate the association between immigrant status and depression?

Contrary to the assumption of a health advantage of immigrants, our results showed no association with depression for men and found that middle-aged and older immigrant women are more likely to screen positive for depression compared to those who were born in Canada. The association of heightened depression was not attenuated when 32 covariates including socioeconomic status, health behaviors, nutrition status, and dietary habits were taken into account, suggesting that these may not be the main determinants of depression among immigrants. One possible explanation is that based on cumulative advantage-disadvantage theory [88,89,90], exposure to migration and acculturation may contribute to stress over the life course and poorer mental health status despite having similar socioeconomic status and lifestyles as middle-aged and older non-immigrants.

Our results showed that middle-aged and older immigrant women who lived in Canada less than 20 years have a higher likelihood of depression compared to both long-term immigrant women and native-born Canadian women. Similar findings were also indicated in a longitudinal study where deterioration of self-rated health occurred among females and ethnic minority immigrants over 4 years after arriving in Canada [68]. Our study also suggested that the trajectory of deterioration in mental health among middle-aged and older immigrants might not be a linear relationship. As suggested by Wu and colleagues [28], a reverse U shape association may occur between length of stay and depression among immigrants. This would be consistent with the disillusionment model which suggests that newly arrived immigrants may experience “euphoria of arrival” and have similar or better health status than native-born residents. Subsequently, they enter a period of disillusionment and experience difficulties in the receiving country, and then eventually, adapt to the new environment [91, 92]. Further study examining longitudinal associations will better ascertain these relationships.

Objective 3. Is there an association between dietary intakes and depression after controlling for immigration status?

Similar to previous research [14,15,16,17,18], the consumption of fruits and vegetables was protective for depression. Various anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant components in fruits and vegetables may account for this relationship. Several minerals and vitamins (e.g., magnesium, zinc, selenium) present in fruits and vegetables may reduce plasma concentrations of C-reactive protein, a marker of low-grade inflammation associated with depression [93]. Antioxidants, such as vitamin C, vitamin E, and folic acid, are involved in endothelial cell signaling cascades which reduce the effects of oxidative stress on mental health [94, 95].

Interestingly, in this study chocolate intake was associated with depression. Cocoa, which is found in chocolate, has polyphenolic compounds that have been reported to modulate mental health [96] due to their roles in metal ion (e.g., iron, copper) chelation, modulation of antioxidant enzyme antioxidant ability, and anti-inflammation [97]. The reported effects of cocoa with mental health conditions such as depression are still equivocal [98]. It is also important to note that the chocolate assessed in this study referred to all types including milk and dark chocolate; the latter has 2–3 times more of the beneficial flavanol-rich cocoa. Furthermore, the relationships between chocolate consumption and depression may be impacted by whether it is consumed mindfully or not [99]. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of this study prohibits the determination of causality. Some individuals crave chocolate and its self-soothing qualities when they are depressed [100].

For men, high fiber intakes were associated with depression. High fiber foods contain phytates which bind with trace minerals such as iron, zinc, and manganese and reduces their bioavailability [101]. With increased high fiber intakes less of these nutrients, which are critical for mental health, may be absorbed which can subsequently contribute to depression symptoms [102]. Dietary fiber intake can alter the human gastrointestinal (GI) microbiota, and GI microbe composition is associated with mood in adults. Recent research has suggested that these relationships differ by sex [103].

Surprisingly, higher fat intakes tended to be protective for depression in men. This finding, which seems counterintuitive, may be due to the fact that the measure of fat included all fatty acid types and did not partition them into saturated and unsaturated fat; each type has different relationships with depression [104]. Recent exploratory research suggests that the absorption of bile acid may be impaired in chronic stress [105,106,107] and that intakes of high-fat diets under stress may induce cholesterol metabolism and help to attenuate stress-related outcomes [108].

Similar to previous findings [104], intakes of omega-3 polyunsaturated fats were inversely associated with depression, however this relationship was only shown for men. This appears to be the first study to suggest the relationship between omega-3 fatty acid intake and depression may differ by gender. However, previous investigations have found sex differences for depression outcomes based on the ratio of polyunsaturated fat to saturated fat consumed [109]. Increased omega-3 fatty acid concentration in the diet may influence central nervous system cell membrane fluidity, and phospholipid composition, which may alter the structure and function of the embedded proteins and affect serotonin and dopamine neurotransmission [110].

The disproportionate associations of fruit juice and salty snack intakes with depression found in women may be due to their heightened susceptibility to factors that promote inflammation [111]. The high content of naturally occurring sugars in 100% fruit juice may cause negative health effects similar to those of other sugar-sweetened beverages [112]. Some studies have indicated that sodium reabsorption may be associated with psychological activity. Specifically, the inhibition of renal sodium reabsorption is compensated for by stimulation of the salt appetite and vice versa [111]. Exposure to stress can activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis leading to release of corticosteroids which bind to two types of receptors in the brain: the mineralocorticoid receptor and the glucocorticoid receptor. Individuals with low mineralocorticoid receptor function may be more susceptible to depression [113].

Objective 4. What other factors are associated with depression among Canadians aged 45 to 85 after controlling for immigration status?

Consistent with previous research, our results support that among middle-aged and older adults, those who are women, working-age (45–65 years), married, have lower education, and have less annual income are more likely to experience depression. Previous research has consistently shown that being female and being unmarried are associated with more depressive symptoms [114, 115], while research findings about the interaction between sex and age on depressive symptoms remained inconsistent [116, 117]. The association of depression with lower socioeconomic status is consistent across both cross-sectional investigations [3, 118] and longitudinal research of older adults in the Netherlands [119] and examination of depression and education attainment over the life course in the US [120]. Our study provides further evidence of the gradient effect between income level and depression.

In addition to demographic, social, and economic characteristics, associations between physical health factors and depression were also supported by previous findings. Consistent with a meta-analysis focusing on older adults, presence of chronic disease is an independent risk factor of depression [121]. Longitudinal studies of older adults also indicate that experiencing pain is associated with depression [122]. Having other physical conditions, such as hypertension, are also associated with depression among older adults [123].

With the exception of the association between smoking and depression in men, our findings of no other significant associations between depression and health behaviors were not consistent with previous studies [124,125,126]. Other investigations have indicated that the associations found between smoking and depression and between smoking and heavy drinking are bidirectional [127]. The different results may be due to the variability in measures of substance use that were administered. The lack of association found between physical activity and depression may be due to confounding by factors such as presence of a health condition or having an insufficient sample who were really active [128].

The relationships between depression and nutrition status indicators were both similar and dissimilar to other studies. Like other investigations, our bivariate analyses showed association between excess body weight and depression. However, the multivariable logistic regression results did not show this relationship. This may suggest that the association was attenuated by other factors such as presence of health conditions, or, as indicated by other studies, the relationship between BMI and depression in older adults may be curvilinear [129]. Similar to previous studies, measures of poor nutrition status were associated with depression in older adults [130]. Poor nutrition is closely related to frailty, which can impact overall physical and psychological functioning [131].

Generally speaking, for women, more factors tended to be associated with depression. This may be due to women having heightened susceptibility to inflammation and autoimmune responses [132, 133] which can elevate risk for depression [134, 135]. For women, inflammation tends to affect their feelings of social disconnection to a greater extent than men [136]. In addition, factors such as relationship distress and obesity, which are both associated with depression risk, tend to have greater association with inflammation for women than for men [137]. Women experience several risk factors for inflammation at higher rates than men, including low physical inactivity and childhood adversity [105, 111, 138]. The fluctuation of women’s reproductive hormones throughout the life span, also has implications for inflammation and depression. For example, during the menopausal transition, women experience pronounced hormonal fluctuations which result in diminished estrogen levels following menopause [132, 133] and elevated levels of inflammation [134, 135]. Collectively, these findings suggest that women’s susceptibility to inflammation can contribute to the observed sex differences for depression.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first Canadian study to comprehensively assess associations between depression and various health determinants, including immigration status and nutritional intake. However, the interpretation of the results should be viewed with caution. Given that the data was cross-sectional, the direction of the relationships between depression and the various measures cannot be ascertained. There are many patho-physiological processes that are involved in depression and thus it was impossible to account for all variables that may affect the relationships between depression and different health determinants. The use of self-report measures for many of the variables made misreporting and misclassification possible. This may be particularly the case for the lifetime measure used for smoking status and for the physical activity measurement which only assessed activity in the previous 7 days. Unfortunately, due to limited sample size of relatively recent and mid-term immigrants, larger cohorts of immigrants were analyzed (i.e., < 20 years and ≥20 years) and therefore relationships within more defined sub-groups could not be examined. Suggestions for future investigations include oversampling different immigrant groups to enable sub-population analysis, examining longitudinal data to explore relationship trajectories between depression and health determinants post-settlement, and conducting qualitative work to gain important insights into the quantitative findings.

Conclusions

Depression is a leading cause of disability worldwide. In this study, older immigrant women were more susceptible to depression when compared to Canadian-born women and all men. The differences between women and men may be due to dissimilarities in their susceptibility to inflammatory and autoimmune processes. Successful prevention and treatment of depression among older adults, particularly immigrant women, could have major public health, societal, and economic impacts. Based on our findings, interventions that target social, economic, physical health, and nutrition-related factors that can mitigate inflammatory responses may be particularly important in improving the mental health of older adults. This investigation provides important insights for policy and program development to mitigate depression in older adults, particularly for marginalized groups such as immigrant women.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (www.clsa-elcv.ca) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to de-identified CLSA data.

Abbreviations

- AB SCREENTM II:

-

Abbreviated Seniors in the Community Risk Evaluation for Eating and Nutrition II

- aOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratios

- BMDs:

-

Bone mineral densities

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CES-D-10:

-

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CLSA:

-

Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging

- DEXA:

-

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

- g/L:

-

grams/Litre

- mm Hg:

-

Millimetres mercury

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- WHR:

-

Waist-to-hip ratio

- WHtR:

-

Waist-to-height ratio

References

World Health Organization. Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. 2017.

Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Patten SB, Freedman G, Murray CJ, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10(11):e1001547.

Fiske A, Wetherell JL, Gatz M. Depression in older adults. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2009;5(1):363–89.

Kaup AR, Byers AL, Falvey C, Simonsick EM, Satterfield S, Ayonayon HN, Smagula SF, Rubin SM, Yaffe K. Trajectories of depressive symptoms in older adults and risk of dementia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(5):525–31.

Xiang X, An R. Depression and onset of cardiovascular disease in the US middle-aged and older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(12):1084–92.

Xiang X, An R. The impact of cognitive impairment and comorbid depression on disability, health care utilization, and costs. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(11):1245–8.

Kessler RC. Epidemiology of women and depression. J Affect Disord. 2003;74(1):5–13.

Kessler RC, Bromet EJ. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:119–38.

Wang JL, Schmitz N, Dewa CS. Socioeconomic status and the risk of major depression: the Canadian National Population Health Survey. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64(5):447–52.

Chrysohoou C, Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Das UN, Stefanadis C. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet attenuates inflammation and coagulation process in healthy adults: the ATTICA study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(1):152–8.

Sarandol A, Sarandol E, Eker SS, Erdinc S, Vatansever E, Kirli S. Major depressive disorder is accompanied with oxidative stress: short-term antidepressant treatment does not alter oxidative–antioxidative systems. Hum Psychopharm Clin. 2007;22(2):67–73.

Lai JS, Hiles S, Bisquera A, Hure AJ, McEvoy M, Attia J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary patterns and depression in community-dwelling adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(1):181–97.

Skarupski KA, Tangney CC, Li H, Evans DA, Morris MC. Mediterranean diet and depressive symptoms among older adults over time. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(5):441–5.

Jacka FN, Pasco JA, Mykletun A, Williams LJ, Hodge AM, O'Reilly SL, Nicholson GC, Kotowicz MA, Berk M. Association of Western and traditional diets with depression and anxiety in women. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):305–11.

Jacka FN, Mykletun A, Berk M, Bjelland I, Tell GS. The association between habitual diet quality and the common mental disorders in community-dwelling adults: the Hordaland health study. Psychol Med. 2011;73(6):483–90.

Rienks J, Dobson AJ, Mishra GD. Mediterranean dietary pattern and prevalence and incidence of depressive symptoms in mid-aged women: results from a large community-based prospective study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(1):75–82.

Sanchez-Villegas A, Delgado-Rodriguez M, Alonso A, Schlatter J, Lahortiga F, Majem LS, Martinez-Gonzalez MA. Association of the Mediterranean dietary pattern with the incidence of depression - the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra/University of Navarra follow-up (SUN) cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(10):1090–8.

Kingsbury M, Dupuis G, Jacka F, Roy-Gagnon MH, McMartin SE, Colman I. Associations between fruit and vegetable consumption and depressive symptoms: evidence from a national Canadian longitudinal survey. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(2):155–61.

Hawton K, Casanas ICC, Haw C, Saunders K. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2013;147(1–3):17–28.

Holzel L, Harter M, Reese C, Kriston L. Risk factors for chronic depression--a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2011;129(1–3):1–13.

Pinheiro MB, Ferreira ML, Refshauge K, Maher CG, Ordoñana JR, Andrade TB, Tsathas A, Ferreira PH. Symptoms of depression as a prognostic factor for low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J. 2016;16(1):105–16.

Ryu E, Chamberlain AM, Pendegraft RS, Petterson TM, Bobo WV, Pathak J. Quantifying the impact of chronic conditions on a diagnosis of major depressive disorder in adults: a cohort study using linked electronic medical records. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):114.

Murabito JM, Massaro JM, Clifford B, Hoffmann U, Fox CS. Depressive symptoms are associated with visceral adiposity in a community-based sample of middle-aged women and men. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21(8):1713–9.

Ali JS, McDermott S, Gravel RG. Recent research on immigrant health from statistics Canada's population surveys. Can J Public Health. 2004;95(3):I9–13.

De Maio FG. Immigration as pathogenic: a systematic review of the health of immigrants to Canada. Int J Equity Health. 2010;9(1):27.

Menezes NM, Georgiades K, Boyle MH. The influence of immigrant status and concentration on psychiatric disorder in Canada: a multi-level analysis. Psychol Med. 2011;41(10):2221–31.

Stafford M, Newbold BK, Ross NA. Psychological distress among immigrants and visible minorities in Canada: a contextual analysis. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;57(4):428–41.

Wu Z, Schimmele CM. The healthy migrant effect on depression: variation over time? Can Stud Popul. 2005;32(2):271–95.

De Maio FG, Kemp E. The deterioration of health status among immigrants to Canada. Glob Public Health. 2010;5(5):462–78.

Gonzalez HM, Tarraf W, Whitfield KE, Vega WA. The epidemiology of major depression and ethnicity in the United States. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(15):1043–51.

Reus-Pons M, Mulder CH, Kibele EUB, Janssen F. Differences in the health transition patterns of migrants and non-migrants aged 50 and older in southern and western Europe (2004-2015). BMC Med. 2018;16(1):57.

Smith KL, Matheson FI, Moineddin R, Glazier RH. Gender, income and immigration differences in depression in Canadian urban centres. Can J Public Health. 2007;98(2):149–53.

Kuo BC, Chong V, Joseph J. Depression and its psychosocial correlates among older Asian immigrants in North America: a critical review of two decades' research. J Aging Health. 2008;20(6):615–52.

Taloyan M, Lofvander M. Depression and gender differences among younger immigrant patients on sick leave due to chronic back pain: a primary care study. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2014;15(1):5–14.

Vega WA, Sribney WM, Achara-Abrahams I. Co-occurring alcohol, drug, and other psychiatric disorders among Mexican-origin people in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(7):1057–64.

Gavin AR, Rue T, Takeuchi D. Racial/ethnic differences in the association between obesity and major depressive disorder: findings from the comprehensive psychiatric epidemiology surveys. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(5):698–708.

McDonald JT, Kennedy S. Is migration to Canada associated with unhealthy weight gain? Overweight and obesity among Canada's immigrants. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(12):2469–81.

Sanou D, O'Reilly E, Ngnie-Teta I, Batal M, Mondain N, Andrew C, Newbold BK, Bourgeault IL. Acculturation and nutritional health of immigrants in Canada: a scoping review. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16(1):24–34.

Bas-Sarmiento P, Saucedo-Moreno MJ, Fernandez-Gutierrez M, Poza-Mendez M. Mental health in immigrants versus native population: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2017;31(1):111–21.

Setia MS, Quesnel-Vallee A, Abrahamowicz M, Tousignant P, Lynch J. Different outcomes for different health measures in immigrants: evidence from a longitudinal analysis of the National Population Health Survey (1994-2006). J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(1):156–65.

Lebrun LA. Effects of length of stay and language proficiency on health care experiences among immigrants in Canada and the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(7):1062–72.

Takeuchi DT, Zane N, Hong S, Chae DH, Gong F, Gee GC, Walton E, Sue S, Alegria M. Immigration-related factors and mental disorders among Asian Americans. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):84–90.

Torres L, Driscoll MW, Voell M. Discrimination, acculturation, acculturative stress, and Latino psychological distress: a moderated mediational model. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2012;18(1):17–25.

Das-Munshi J, Leavey G, Stansfeld SA, Prince MJ. Migration, social mobility and common mental disorders: critical review of the literature and meta-analysis. Ethn Health. 2012;17(1–2):17–53.

Guruge S, Thomson MS, George U, Chaze F. Social support, social conflict, and immigrant women's mental health in a Canadian context: a scoping review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2015;22(9):655–67.

George U, Chaze F, Brennenstuhl S, Fuller-Thomson E. “Looking for work but nothing seems to work”: the job search strategies of internationally trained engineers in Canada. J Int Migr Integr. 2012;13(3):303–23.

Chen W, Hall BJ, Ling L, Renzaho AM. Pre-migration and post-migration factors associated with mental health in humanitarian migrants in Australia and the moderation effect of post-migration stressors: findings from the first wave data of the BNLA cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(3):218–29.

Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R, Vigod S, Dennis CL. Prevalence of postpartum depression among immigrant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;70:67–82.

Alegria M, Alvarez K, DiMarzio K. Immigration and mental health. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2017;4(2):145–55.

Kalich A, Heinemann L, Ghahari S. A scoping review of immigrant experience of health care access barriers in Canada. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016;18(3):697–709.

Fuller-Thomson E, Brennenstuhl S, Cooper R, Kuh D. An investigation of the healthy migrant hypothesis: pre-emigration characteristics of those in the British 1946 birth cohort study. Can J Public Health. 2016;106(8):e502–8.

Jatrana S, Pasupuleti SS, Richardson K. Nativity, duration of residence and chronic health conditions in Australia: do trends converge towards the native-born population? Soc Sci Med. 2014;119:53–63.

Kennedy S, Kidd MP, McDonald JT, Biddle N. The healthy immigrant effect: patterns and evidence from four countries. J Int Migr Integr. 2015;16(2):317–32.

Riosmena F, Wong R, Palloni A. Migration selection, protection, and acculturation in health: a binational perspective on older adults. Demography. 2013;50(3):1039–64.

Shor E, Roelfs D, Vang ZM. The "Hispanic mortality paradox" revisited: meta-analysis and meta-regression of life-course differentials in Latin American and Caribbean immigrants' mortality. Soc Sci Med. 2017;186:20–33.

Wallace M, Kulu H. Low immigrant mortality in England and Wales: a data artefact? Soc Sci Med. 2014;120:100–9.

Vang ZM, Sigouin J, Flenon A, Gagnon A. Are immigrants healthier than native-born Canadians? A systematic review of the healthy immigrant effect in Canada. Ethn Health. 2017;22(3):209–41.

Lariscy JT, Hummer RA, Hayward MD. Hispanic older adult mortality in the United States: new estimates and an assessment of factors shaping the Hispanic paradox. Demography. 2015;52(1):1–14.

Thomson EF, Nuru-Jeter A, Richardson D, Raza F, Minkler M. The Hispanic paradox and older adults' disabilities: is there a healthy migrant effect? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(5):1786–814.

Pasupuleti SS, Jatrana S, Richardson K. Effect of nativity and duration of residence on chronic health conditions among Asian immigrants in Australia: a longitudinal investigation. J Biosoc Sci. 2016;48(3):322–41.

Gushulak BD, Pottie K, Hatcher Roberts J, Torres S, DesMeules M. On behalf of the Canadian collaboration for immigrant and refugee health. Migration and health in Canada: health in the global village. CMAJ. 2011;183(12):E952–8.

Abraido-Lanza AF, Dohrenwend BP, Ng-Mak DS, Turner JB. The Latino mortality paradox: a test of the "salmon bias" and healthy migrant hypotheses. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(10):1543–8.

Abraido-Lanza AF, Chao MT, Florez KR. Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation? Implications for the Latino mortality paradox. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(6):1243–55.

Goel MS, McCarthy EP, Phillips RS, Wee CC. Obesity among US immigrant subgroups by duration of residence. JAMA. 2004;292(23):2860–7.

Bethel JW, Schenker MB. Acculturation and smoking patterns among Hispanics: a review. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(2):143–8.

Reiss K, Schunck R, Razum O. Effect of length of stay on smoking among Turkish and eastern European immigrants in Germany—interpretation in the light of the smoking epidemic model and the acculturation theory. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(12):15030.

Fuller-Thomson E, Noack AM, George U. Health decline among recent immigrants to Canada: findings from a nationally-representative longitudinal survey. Can J Public Health. 2011;102(4):273–80.

Kim IH, Carrasco C, Muntaner C, McKenzie K, Noh S. Ethnicity and postmigration health trajectory in new immigrants to Canada. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(4):e96–104.

Subedi RP, Rosenberg MW. Determinants of the variations in self-reported health status among recent and more established immigrants in Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2014;115:103–10.

Omariba DW, Ng E, Vissandjee B. Differences between immigrants at various durations of residence and host population in all-cause mortality, Canada 1991-2006. Popul Stud (Camb). 2014;68(3):339–57.

Baum F, Lawless A, Williams C. Health in All Policies from international ideas to local implementation: policies, systems and organizations. In: Health promotion and the policy process: practical and critical theories; 2013. p. 188–217.

Davison KM, D’Andreamatteo C, Mitchell S, Vanderkooy P. The development of a national nutrition and mental health research agenda with comparison of priorities among diverse stakeholders. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(4):712–25.

Raina PS, Wolfson C, Kirkland SA, Griffith LE, Oremus M, Patterson C, Tuokko H, Penning M, Balion CM, Hogan D. The Canadian longitudinal study on aging (CLSA). Can J Aging. 2009;28(3):221–9.

Stinchcombe A, Wilson K, Kortes-Miller K, Chambers L, Weaver B. Physical and mental health inequalities among aging lesbian, gay, and bisexual Canadians: cross-sectional results from the Canadian longitudinal study on aging (CLSA). Can J Public Health. 2018;109(5-6):833-44.

Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77–84.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, et al. 2017 ACC, AHA, AAPA, ABC, ACPM, AGS, APhA, ASH, ASPC, NMA, PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1269–324.

Statistics Canada. Heavy Drinking. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-625-x/2017001/article/54861-eng.htm. .

World Health Organization. Waist circumference and waist-hip ratio: report of a WHO expert consultation, Geneva, 8–11 December 2008. 2011.

Browning LM, Hsieh SD, Ashwell M. A systematic review of waist-to-height ratio as a screening tool for the prediction of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: 0–5 could be a suitable global boundary value. Nutr Res Rev. 2010;23(2):247–69.

Douketis JD, Paradis G, Keller H, Martineau C. Canadian guidelines for body weight classification in adults: application in clinical practice to screen for overweight and obesity and to assess disease risk. CMAJ. 2005;172(8):995–8.

Guerra R, Fonseca I, Pichel F, Restivo M, Amaral T. Handgrip strength cutoff values for undernutrition screening at hospital admission. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68(12):1315.

Lourenço RA, Pérez-Zepeda M, Gutiérrez-Robledo L, García-García FJ, Rodríguez ML. Performance of the European working group on sarcopenia in older people algorithm in screening older adults for muscle mass assessment. Age Ageing. 2014;44(2):334–8.

Yoshida D, Suzuki T, Shimada H, Park H, Makizako H, Doi T, Anan Y, Tsutsumimoto K, Uemura K, Ito T. Using two different algorithms to determine the prevalence of sarcopenia. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14:46–51.

World Health Organization. 2011a. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. (WHO/NMH/NHD/MNM/11.1). http://www.who.int/vmnis/indicators/haemoglobin.pdf, Accessed 28 Feb 2019

Shatenstein B, Payette H. Evaluation of the relative validity of the short diet questionnaire for assessing usual consumption frequencies of selected nutrients and foods. Nutrients. 2015;7(8):6362–74.

Greenland S, Finkle WD. A critical look at methods for handling missing covariates in epidemiologic regression analyses. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:1255–64.

IBM Corp. ReleasedIBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 22.0. Armonk: IBM Corp; 2013.

Dannefer D. Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58(6):S327–37.

Ferraro KF, Shippee TP. Aging and cumulative inequality: how does inequality get under the skin? Gerontologist. 2009;49(3):333–43.

Riosmena F, Everett BG, Rogers RG, Dennis JA. Negative acculturation and nothing more? Cumulative disadvantage and mortality during the immigrant adaptation process among Latinos in the United States. Int Migr Rev. 2015;49(2):443–78.

Beiser M. The health of immigrants and refugees in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2005;96(Suppl 2):S30–44.

Tyhurst L. Displacement and migration. A study in social psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry. 1951;107(8):561–8.

Khanzode SD, Dakhale GN, Khanzode SS, Saoji A, Palasodkar R. Oxidative damage and major depression: the potential antioxidant action of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors. Redox Rep. 2003;8:365–70.

McMartin SE, Jacka FN, Colman I. The association between fruit and vegetable consumption and mental health disorders: evidence from five waves of a national survey of Canadians. Prev Med. 2013;56:225–30.

Maes M, De Vos N, Pioli R, Demedts P, Wauters A, Neels H, Christophe A. Lower serum vitamin E concentrations in major depression. Another marker of lowered antioxidant defenses in that illness. J Affect Disord. 2000;58:241–6.

Visioli F, Burgos-Ramos E. Selected micronutrients in cognitive decline prevention and therapy. J Nutr Biochem. 2015;26(2):165–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2014.10.002.

Visioli F, Bernaert H, Corti R, Ferri C, Heptinstall S, Molinari E, Poli A, Serafini M, Smit HJ, Vinson JA, Violi F, Paoletti R. Chocolate, lifestyle, and health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2009;49(4):299–312.

García-Blanco T, Dávalos A, Visioli F. Tea, cocoa, coffee, and affective disorders: vicious or virtuous cycle? J Affect Disord. 2017;15(224):61–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.033.

Meier BP, Noll SW, Molokwu OJ. The sweet life: the effect of mindful chocolate consumption on mood. Appetite. 2017;108:21–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.09.018.

Parker G, Crawford J. Chocolate craving when depressed: a personality marker. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:351–2.

Schlemmer U, Frolich W, Prieto RM, Grases F. Phytate in foods and significance for humans: food sources, intake, processing, bioavailability, protective role and analysis. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2009;53 Suppl 2(S2):S330–75.

Davison KM, Kaplan BJ. Nutrient intakes are correlated with overall psychiatric functioning in adults with mood disorders. Can J Psychiatr. 2012;57(2):85–92.

Taylor AM, Thompson SV, Edwards CG, Musaad SMA, Khan NA, Holscher HD. Associations among diet, the gastrointestinal microbiota, and negative emotional states in adults. Nutr Neurosci. 2019;22:1–10.

Lai JS, Oldmeadow C, Hure AJ, McEvoy M, Hiles SA, Boyle M, Attia J. Inflammation mediates the association between fatty acid intake and depression in older men and women. Nutr Res. 2016;36(3):234–45.

Watanabe M, Houten SM, Mataki C, Christoffolete MA, Kim BW, Sato H, Messaddeq N, Harney JW, Ezaki O, Kodama T, Schoonjans K, Bianco AC, Auwerx J. Bile acids induce energy expenditure by promoting intracellular thyroid hormone activation. Nature. 2006;439:484–9.

Lefebvre P, Cariou B, Lien F, Kuipers F, Staels B. Role of bile acids and bile acid receptors in metabolic regulation. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:147–91.

Silvennoinen R, Quesada H, Kareinen I, Julve J, Kaipiainen L, Gylling H, Blanco-Vaca F, Escola-Gil JC, Kovanen PT, Lee-Rueckert M. Chronic intermittent psychological stress promotes macrophage reverse cholesterol transport by impairing bile acid absorption in mice. Phys Rep. 2015;3:e12402.

Otsuka A, Shiuchi T, Chikahisa S, Shimizu N, Séi H. Sufficient intake of high-fat food attenuates stress-induced social avoidance behavior. Life Sci. 2019;219:219–30.

Akbaraly TN, Sabia S, Shipley MJ, Batty GD, Kivimaki M. Adherence to healthy dietary guidelines and future depressive symptoms: evidence for sex differentials in the Whitehall II study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(2):419–27. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.041582.

Deacon G, Kettle C, Hayes D, Dennis C, Tucci J. Omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and the treatment of depression. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57(1):212–23.

Derry HM, Padin AC, Kuo JL, Hughes S, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Sex differences in depression: does inflammation play a role? Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(10):78.

Wojcicki JM, Heyman MB. Reducing childhood obesity by eliminating 100% fruit juice. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1630–3.

Shimizu Y, Kadota K, Koyamatsu J, Yamanashi H, Nagayoshi M, Noda M, Nishimura T, Tayama J, Nagata Y, Maeda T. Salt intake and mental distress among rural community-dwelling Japanese men. J Physiol Anthropol. 2015;34:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40101-015-0064-4.

Glaesmer H, Riedel-Heller S, Braehler E, Spangenberg L, Luppa M. Age- and gender-specific prevalence and risk factors for depressive symptoms in the elderly: a population-based study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(8):1294–300.

Yan XY, Huang SM, Huang CQ, Wu WH, Qin Y. Marital status and risk for late life depression: a meta-analysis of the published literature. J Int Med Res. 2011;39(4):1142–54.

Djernes JK. Prevalence and predictors of depression in populations of elderly: a review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(5):372–87.

Vink D, Aartsen MJ, Schoevers RA. Risk factors for anxiety and depression in the elderly: a review. J Affect Disord. 2008;106(1–2):29–44.

Everson SA, Maty SC, Lynch JW, Kaplan GA. Epidemiologic evidence for the relation between socioeconomic status and depression, obesity, and diabetes. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(4):891–5.

Koster A, Bosma H, Kempen GI, Penninx BW, Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, van Eijk JT. Socioeconomic differences in incident depression in older adults: the role of psychosocial factors, physical health status, and behavioral factors. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(5):619–27.

Miech RA, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Wright BRE, Silva PA. Low socioeconomic status and mental disorders: a longitudinal study of selection and causation during young adulthood. Am J Sociol. 1999;104(4):1096–131.

Chang-Quan H, Xue-Mei Z, Bi-Rong D, Zhen-Chan L, Ji-Rong Y, Qing-Xiu L. Health status and risk for depression among the elderly: a meta-analysis of published literature. Age Ageing. 2009;39(1):23–30.

Sanders JB, Comijs HC, Bremmer MA, Deeg DJ, Beekman AT. A 13-year prospective cohort study on the effects of aging and frailty on the depression–pain relationship in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(7):751–7.

Patten SB, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, Campbell NR, Eliasziw M, Campbell TS. Major depression as a risk factor for high blood pressure: epidemiologic evidence from a national longitudinal study. Psychol Med. 2009;71(3):273–9.

Onder G, Penninx BW, Cesari M, Bandinelli S, Lauretani F, Bartali B, Gori AM, Pahor M, Ferrucci L. Anemia is associated with depression in older adults: results from the InCHIANTI study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(9):1168–72.

Mendelsohn C. Smoking and depression--a review. Aust Fam Physician. 2012;41(5):304–7.

Boden JM, Fergusson DM. Alcohol and depression. Addiction. 2011;106(5):906–14.

An R, Xiang X. Smoking, heavy drinking, and depression among US middle-aged and older adults. Prev Med. 2015;81:295–302.

Kok RM, Reynolds CF 3rd. Management of depression in older adults: a review. JAMA. 2017;317(20):2114–22.

Lee J-H, Park S, Ryoo J-H, Oh C-M, Choi J-M, McIntyre R, Mansur R, Kim H, Hales S, Jung J. U-shaped relationship between depression and body mass index in the Korean adults. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;45:72–80.

Abizanda P, Sinclair A, Barcons N, Lizan L, Rodriguez-Manas L. Costs of malnutrition in institutionalized and community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(1):17–23.

Lorenzo-López L, Maseda A, de Labra C, Regueiro-Folgueira L, Rodríguez-Villamil JL, Millán-Calenti JC. Nutritional determinants of frailty in older adults: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):108.

Quintero OL, Amador-Patarroyo MJ, Montoya-Ortiz G, Rojas-Villarraga A, Anaya JM. Autoimmune disease and gender: plausible mechanisms for the female predominance of autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2012;38(2–3):J109–19.

Yang Y, Kozloski M. Sex differences in age trajectories of physiological dysregulation: inflammation, metabolic syndrome, and allostatic load. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(5):493–500.

Duivis HE, de Jonge P, Penninx BW, Na BY, Cohen BE, Whooley MA. Depressive symptoms, health behaviors, and subsequent inflammation in patients with coronary heart disease: prospective findings from the heart and soul study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(9):913–20.

Benros ME, Waltoft BL, Nordentoft M, Østergaard SD, Eaton WW, Krogh J, Mortensen PB. Autoimmune diseases and severe infections as risk factors for mood disorders: a nationwide study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(8):812–20.

Moieni M, Irwin MR, Jevtic I, Olmstead R, Breen EC, Eisenberger NI. Sex differences in depressive and socioemotional responses to an inflammatory challenge: implications for sex differences in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(7):1709–16.

Donoho CJ, Crimmins EM, Seeman TE. Marital quality, gender, and markers of inflammation in the MIDUS cohort. J Marriage Fam. 2013;75(1):127–41.

Choi J, Joseph L, Pilote L. Obesity and C-reactive protein in various populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2013;14(3):232–44.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the CLSA National Coordinating Centre for providing the data for this analysis. This research was made possible using the data/biospecimens collected by the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). Funding for the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) is provided by the Government of Canada through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) under grant reference: LSA 9447 and the Canada Foundation for Innovation. This research has been conducted using the CLSA dataset Baseline Tracking Dataset version 3.4, Baseline Comprehensive Dataset version 4.0, under Application Number 170605.” The CLSA is led by Drs. Parminder Raina, Christina Wolfson and Susan Kirkland.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this manuscript are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging.

Funding

Part of this study was funded through EFT’s Sandra Rotman Endowed Chair funds and KMD’s Fulbright Canada Research Chair funds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EFT, KMD, KK, HT, and LS developed the analysis plan. KMD and LS conducted the analysis with the direction of EFT. KMD, LS, YL & EFT wrote the first manuscript draft and all team members provided feedback. KMD, LS, EFT and YL made the final revisions. EFT supervised all components of the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All research conducted in preparation for, or as part of, the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging abides by the requirements of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and relevant institutions for ethical conduct and privacy protection in health research. The protocol of the CLSA has been reviewed and approved by 13 research ethics boards across Canada. The secondary analysis of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging data conducted in this paper was approved by the University of Toronto’s Health Sciences Research Ethics Board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Davison, K.M., Lung, Y., Lin, S.(. et al. Depression in middle and older adulthood: the role of immigration, nutrition, and other determinants of health in the Canadian longitudinal study on aging. BMC Psychiatry 19, 329 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2309-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published: