Abstract

Background

Clinically operated community-based residential rehabilitation units (Community Rehabilitation Units) are resource intensive services supporting a small proportion of the people with severe and persisting mental illness who experience difficulties living in the community. Most consumers who engage with these services will be diagnosed with schizophrenia or a related disorder. This review seeks to: generate a typology of service models, describe the characteristics of the consumers accessing these services, and synthesise available evidence about consumers’ service experiences and outcomes.

Method

A systematic review was undertaken to identify studies describing Community Rehabilitation Units in Australia, consumer characteristics, and evidence about consumer experiences and outcomes. Search strings were applied to multiple databases; additional records were identified through snowballing. Records presenting unique empirical research were subject to quality appraisal.

Results

The typology defined two service types, Community-Based Residential Care (C-BRC), which emerged in the context of de-institutionalisation, and the more recent Transitional Residential Rehabilitation (TRR) approach. Key differentiating features were the focus on transitional care and ‘recovery’ under TRR. Schizophrenia spectrum disorders were the most common primary diagnosis under both service types. TRR consumers were more likely to be male, referred from community settings, and less likely to be subject to involuntary treatment. Regarding outcomes, the limited quantitative evidence (4 records, 2 poor quality) indicated C-BRC was successful in supporting the majority of consumers transferred from long-term inpatient care to remain out of hospital. All qualitative research conducted in C-BRC settings was assessed to be of poor quality (3 records). No methodologically sound quantitative evidence on the outcomes of TRR was identified. Qualitative research undertaken in these settings was of mixed quality (9 records), and the four records exploring consumer perspectives identified them as valuing the service provided.

Conclusions

While there is qualitative evidence to suggest consumers value the support provided by Community Rehabilitation Units, there is an absence of methodologically sound quantitative research about the consumer outcomes achieved by these services. Given the ongoing and increasing investment in these facilities within the Australian context, there is an urgent need for high-quality research examining their efficiency and effectiveness.

Trial registration

PROSPERO (CRD42018097326).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The provision of clinically-operated rehabilitation in a community residential setting (Community Rehabilitation Units) reflects one approach to supporting people with severe and persisting mental illness to manage in the community. Most of the consumers who engage with mental health rehabilitation services will be diagnosed with schizophrenia or a related psychotic disorder [1, 2]. Schizophrenia is a low prevalence disorder associated with high levels of disability and societal costs [3, 4]. People affected by schizophrenia have varied responses to routine care, and many will continue to experience considerable functional deficits despite receiving optimal treatment. The positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and cognitive impairments associated with the disorder can detrimentally affect the capacity to maintain stable accommodation in the community.

Community Rehabilitation Units emerged in the context of de-institutionalisation. The initial goal was to assist long-stay inpatients in returning to community living in an appropriately supported ‘home-like’ environment [5]. Community Rehabilitation Units are now typically transitional in focus, aiming to help consumers to reside in more independent living situations by the time of discharge. Alternative approaches such as Housing First, which are focussed around the issue of homelessness rather than clinical rehabilitation, have been increasingly championed in North America. These models emphasise provision of permanent accommodation and the mobilisation of relevant support around a consumer’s own residence in the community [6,7,8]. Advocates for Housing First style approaches criticise clinically operated residential services for their limited evidence base [6, 9, 10] and ethical issues associated with making the provision of accommodation conditional on engagement with treatment [6, 7, 11]. Despite these criticisms, continued growth in the availability of different models of Community Rehabilitation Units such as Community Care Units and Community Rehabilitation Centres has occurred in Australia over the past two decades [1, 10, 12]. This discrepancy further highlights the need for increased definitional clarity and evidence regarding the characteristics and outcomes of consumers of these services [9].

This review aims to provide definitional clarity about the types of clinically operated Community Rehabilitation Units in the Australian context, and to examine the associated evidence base critically. Specifically, this review seeks to: (1) generate a typology of service models, (2) describe the characteristics of the consumers who access these services, and (3) synthesise the available evidence about consumers’ service experiences and outcomes.

Methods

The systematic review followed the PRISMA guidelines [13]. The protocol for the review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42018097326) [14].

Eligibility criteria

Records were sought that described: (1) Australian Community Rehabilitation Units for people affected by severe and persisting mental illness, (2) the characteristics of the consumers engaging with these services, and (3) their service experiences and outcomes. Eligibility criteria for inclusion in the systematic review were a service focus on adults (18–65 years) with schizophrenia and related disorders. Rehabilitation units targeting consumers aged < 18 years or > 65 years, non-psychotic disorders (e.g. drug and alcohol, acquired brain injury, or physical rehabilitation) or specifically dual diagnosis consumers were excluded. These exclusion criteria related to the focus of the service model. There was no exclusion of consumer data from included records based on diagnosis or co-morbidity.

Databases were searched from 1995 onwards. This limit was applied as these services emerged in the context of the deinstitutionalisation process [15] with the first Community Care Unit opening in Victoria in 1996 [16]. No language specifiers were used. No exclusions were made based on study type, with emphasis placed instead on the assessment of the quality of included studies.

Information sources

Parallel strategies were employed to identify relevant grey-literature using internet-based searches and published literature in academic databases (PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO and EmBASE).

Search strategy

Full details of the search strategy are provided in Additional file 1: Literature search strategy. The initial search string applied to the PubMED database is illustrative of the process undertaken: “schizophrenia” [MeSH Terms] OR “schizophrenia” [All Fields]) AND (“rehabilitation” [Subheading] OR “rehabilitation” [All Fields] OR “rehabilitation” [MeSH Terms]) AND residential [All Fields]) AND (“1995/01/01” [PDAT]: “3000/12/31” [PDAT]).

Study selection

Final extraction of records from all databases occurred on the 08/02/2018. Records were sequentially imported into an Endnote X8 database, and duplicates were removed. Two authors (SP & GH) independently screened records for eligibility at the title and abstract level. Additional records were identified through snowballing [17], with the reference lists of records assessed at the full-text level inspected to identify relevant documents. Attempts were made to contact authors of included records to identify relevant research and documentation.

Quality appraisal

Records presenting unique quantitative and/or qualitative research data were subject to quality appraisal (full appraisals are provided in Additional file 2: Quality appraisal). Given the anticipated prominence of non-comparative methodologies in the published literature, the decision was made to rely on methodologically targeted quality appraisal instruments. Relevant checklists from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NIH) were used in the appraisal of ‘observational cohort and cross-sectional studies’, ‘systematic review and meta-analyses’, ‘case series studies’, ‘before-after (pre-post) studies with no control groups’, and ‘observational cohort and cross-sectional studies’ [18]. Studies presenting qualitative data, and the qualitative components of mixed-methods studies were assessed using the CASP Qualitative Checklist [19]. As the CASP Qualitative Checklist does not produce a global quality rating, the tripartite global rating system (Good, Fair, Poor) used in the NIH checklists was also applied to these records. Two of the authors (SP & GH), completed the quality assessments independently, and a final rating was determined following discussion to reach consensus. For studies where SP was one of the authors, DS and GH completed the quality appraisal.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data extraction was completed independently by two authors (SP & GH). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion to reach consensus. Relevant content was extracted into matrices. Data of interest included descriptive information outlining service models (e.g. physical environment, philosophy of care, and ‘treatment and support’), service user characteristics (e.g. age, sex, diagnostic information, and chlorpromazine dose equivalence), and quantitative and qualitative research findings (e.g. outcomes, comparison with other services, consumer and staff perspectives). Descriptive data about service models were synthesised into a domains-based classification system [20], with the emergent typology derived from key emphases in the descriptive content. The typology was then used to organise the results into meaningful groups for interpretation.

Descriptive data regarding service user characteristics was pooled across studies, with means for service types and the associated models subsequently derived. Where data was available across both service types, differences in frequency of dichotomous variables was statistically compared using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Fisher’s exact test was applied when the total sample size for pooled data was < 1000 cases [21] or if the frequency in any of the 2 × 2 cells was less than five [22]. A p ≤ .01 significance level was adopted to accommodate for the multiple comparisons and reduce the risk of Type 1 error. The absence of consistent documentation of standard deviations/standard errors for continuous variables (age and chlorpromazine dose equivalence) prohibited statistical comparison of the pooled means for these variables.

In relation to outcome data, no statistical synthesis was pre-specified or completed for the quantitative data. Findings from quantitative and qualitative studies were synthesised and tabulated.

Results

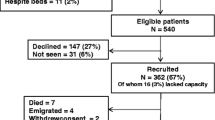

As shown in Fig. 1, 33 records were included in the qualitative synthesis – 24 provided information about service description, 16 provided descriptive data on consumers, and 16 presented data on service experience and outcomes.

Typology of Australian community rehabilitation units

From the 24 records providing service descriptions, two types of Community Rehabilitation Units were identified– the original Community-Based Residential Care (C-BRC) type operating from the mid-1990s until the early 2000s, and the more recent Transitional Residential Rehabilitation (TRR) type (see Table 1 & Additional file 3: Service types and models). These types and the associated named service models differed in the physical environment, philosophy of care, and the available treatment/support.

C-BRC service models emerged to meet the needs of institutionalised people with severe mental illness, predominantly schizophrenia, transitioning to community-based care. Service models associated with the C-BRC type were the Community Residences in New South Wales [23] and Community Care Units in Victoria [15, 24, 25]. These services focused on the provision of accommodation in a cluster housing configuration, in addition to rehabilitation and support to people affected by severe and persisting mental illness. Key features were the availability of 24-h clinical support and an individualised treatment focus on living skills development and community integration. Group-based therapies/programmes were explicitly de-emphasised under the original Community Care Unit model [26] and were not an essential feature of Community Residences. While C-BRC services were initially intended to provide a permanent residence, by the start of the twenty-first century their focus shifted towards a more transitional model of support [24, 27, 28].

The TRR type is distinct from C-BRC in its emphasis on the transitional nature of rehabilitation support as well as the inclusion of ‘recovery’ as part of the philosophy of care. The shift to a transitional focus coincided with: the initial cohort consumers in C-BRC services not requiring 24-h support on an ongoing basis [23, 24, 27]; most of the initial C-BRC-Community Care Unit cohort transitioning to more independent settings in the community [24, 27]; and an emergent emphasis on recovery-oriented care in mental health policy and planning frameworks [10, 29, 30]. Service models aligning with the TRR type are the Community Care Units in Queensland and Victoria [10], Community Rehabilitation Centres in South Australia [31], the Community Recovery Program in Victoria [32], and Hawthorne House in Western Australia [33]. Cluster housing remains the most common environmental configuration for TRR type services, and a focus on independent living or dual occupancy units predominates. Under TRR, there is greater emphasis on the availability of individual and group therapies/programs. Since 2014, deviations from the traditional clinical staffing configuration have emerged, including the substantial integration of peer support workers under the ‘Integrated Staffing Model’ and partnerships with Non-Government Organisations [32]. These alternative staffing configurations have been linked explicitly to the goal of further realising recovery-oriented care [29, 32, 34].

Characteristics of consumers of community rehabilitation units in Australia

Data describing consumer characteristics from 15 records were organised according to the service typology in Tables 2 and 3 (additional detail available in Additional file 4: Consumer characteristics). There were limitations in the consistency and comparability of reported data. Variables reported in 50% or more of records for both C-BRC and TRR services were: age, sex, mode of referral, the presence of an involuntary treatment order, primary diagnosis, and total chlorpromazine dose equivalence of antipsychotic medication. Across both service types, most consumers were males aged in their 30s–40s with a primary diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder.

Differences arose in the characteristics of consumers from the C-BRC and TRR service types. TRR consumers were significantly more likely to be male (X2 19.98, p < .01) and to be referred from the community rather than an inpatient service (Fisher exact test, p < .01). Schizophrenia spectrum disorders were the most common primary diagnosis across both service types, although this was significantly less frequent within the TRR service type (X2 21.24, p < .01). TRR consumers were also significantly less likely to be subject to an involuntary treatment order (X2 106.24, p < .01). C-BRC and TRR consumers did not differ significantly with respect to the frequency of being born in Australia (Fisher exact test, p = 0.68), or rates of comorbid disorders (substance use (Fisher exact test p = 0.78), developmental disorders (Fisher exact test, p = 0.07), and physical illness (Fisher exact test, p = 0.16).

Statistical comparison of the mean values for age and chlorpromazine dose equivalence between the C-BRC and TRR groups could not be performed as standard deviations/standard errors were not reliably reported. Descriptive statistics suggest divergence between the C-BRC and TRR services, in that consumers entering the more recent TRR services were younger (pooled x̅ 35, range of available means 30–39; versus 40 years, range of available means 38–43), and on lower total chlorpromazine dose equivalence of antipsychotic medication (pooled x̅ 614, range of available means 573-728 mg/day; versus 878 mg/day, range of available means 936-1127 mg/day).

Service experiences and outcomes

With regards to quantitative research, only six records were identified. Findings from these studies are detailed in Table 4 (with additional detail in Additional file 5: Included research). Meta-analysis and statistical assessment of publication bias and sensitivity analysis were not appropriate given the insufficient number of comparable studies [35]. Follow-up outcome data was available from two C-BRC studies assessed as ‘fair’ quality. These studies found most consumers remained in the community at long-term follow-up [23, 24], with one study noting high levels of ongoing disability [24]. One ‘poor’ quality report presented follow-up outcome data for the TRR type; the favourable pre-post outcomes with respect to reduced inpatient bed-days and symptoms observed in this study should be interpreted cautiously [31].

Twelve records presented qualitative research findings that considered a range of stakeholder perspectives (consumer, staff and family). Findings are detailed in Table 5 (see also Additional file 5: Included research), and the findings relating to consumer experiences, which reflect the majority focus of the qualitative research, is additionally summarised in text. Consumer reflections about their expectations and experience of care at Community Rehabilitation Units were consistently positive, regardless of service type and name. Two studies explored long-term follow-up in C-BRC services. These studies described ongoing challenges faced by consumers, including impoverished social networks [23, 24] and accommodation instability [24]. All records presenting qualitative findings relating to C-BRC services were assessed to be of poor quality. Seven of the nine records considering TRR models focused on Community Care Units, which were of mixed quality (Good = 4, Fair = 1, Poor = 2); the remaining two records from non-Community Care Unit settings were assessed to be of poor quality.

Discussion

This systematic review identified core features of Australian Community Rehabilitation Units as the provision of 24-h rehabilitation focused support in a community-based residential setting to mental health consumers primarily diagnosed with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Two distinct service types were identified: the original C-BRC type that emerged in the context of deinstitutionalisation, and the more recent TRR type which replaced this from the early 2000s. TRR services differed from C-BRC in their transitional (time-limited) focus and emphasis on recovery-oriented care. Significant differences were present in the profile of consumers engaged with TRR and the earlier C-BRC services. Specifically, TRR consumers are more likely to be male, referred from the community and treated voluntarily, and less likely to have a primary diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. The extent to which these changes relate to shifts in relevant mental health policy needs to be considered.

Quantitative research exploring the outcomes of Community Rehabilitation Units is limited. There is evidence to suggest that C-BRC services met their original goal of avoiding hospitalisation for most consumers initially transferred from long-stay inpatient care. Additionally, the need for 24-h supervision declined over time. The transition to community-based care was associated with improvements in quality of life. There is an absence of methodologically sound quantitative evidence considering the outcomes achieved for consumers engaged with the current TRR service type.

Methodological concerns in qualitative research conducted in these settings were commonly identified. All qualitative research conducted in C-BRC settings and in non-Community Care Unit TRR settings was assessed to be of ‘poor’ quality. Qualitative research consistently reported favourable expectations and experiences of care at Community Rehabilitation Units by consumers and their families across both service types. Consumers and staff of TRR services articulate understandings of the service consistent with the designated service models. However, there is an absence of follow-up qualitative data from former TRR consumers, and that available for the original C-BRC cohort suggests consumers may continue to struggle with issues such as social isolation, accommodation instability and disability following the receipt of intensive rehabilitation support.

Putting the findings in context

The typology enhances understanding of the nature and function of Australian Community Rehabilitation Units for people affected by severe and persisting mental illness. Within the Australian context the typology identified potential bases of service non-comparability, whereby even identically named services were discrepant from each other. The matrix conceptually grouping the key emphases of services models supports the appropriateness of comparing extant Australian service models in future research. Additionally, differential features associated with sub-types and specific service models will facilitate the exploration of differences in service outcomes that may emerge. A relevant example of this may be the impact of novel staffing models being trialled, such as the integration of peer support work within the multidisciplinary team and non-government organisation partnerships.

The availability of domains-based classification presents an opportunity to synthesise existing research internationally, and for future research collaboration. By identifying the key emphases of Australian service models, the typology will allow identification of the extent to which these models are similar, and the appropriateness of comparing and synthesising current and future quantitative and qualitative research findings through meta-analytic methods. One potential opportunity for comparison is the overlap identified between the two Australian Community Rehabilitation Unit types, and two of the five types of supported accommodation emerging in the recent English classification system of supported accommodation - ‘The Simple Taxonomy for Supported Accommodation’ (STAX-SA) [36]. C-BRC aligns with ‘Type 1,’ which is characterised by ‘staff on site’, ‘high support’, ‘limited emphasis on move-on’ and ‘congregate setting’. TRR aligns with ‘Type 2,’ which is distinguished from ‘Type 1’ by its ‘strong emphasis on move on’. This alignment suggests the appropriateness of comparing Australian TRR services and English services classified as ‘Type 1’ in future research.

The limitations in research exploring the outcomes for TRR consumers are concerning given the increasing investment in these services [1, 10, 12] and ongoing adaptation of service models in Australia [34]. There continues to be a strong mental health policy emphasis on the provision of community-based alternatives to inpatient psychiatric services [37, 38]. The findings of this systematic review support concerns that this policy drive is uncoupled from the evidence base [9]. Multiple stakeholders and outcomes are relevant to understanding whether these services are achieving their purpose and offering value for money. Important outcome considerations relating to consumers include functional recovery (e.g. gains in employment, accommodation stability, and living skills), clinical recovery (e.g. improvement on symptomatic measures), as well as consumer defined recovery and quality of life. The outcome of service provision on carer burden is another relevant consideration. Outcomes of relevance to service planners include reductions in inpatient psychiatric bed days, emergency department presentations, and other indexes of service utilisation. None of these outcomes are adequately addressed in the literature.

The consistent finding of positive expectations and reflections on the experience of Community Rehabilitation Units by consumers across qualitative studies provides some support for the value and acceptability of these services. Additionally, available research exploring consumer’s commencement expectations of TRR services found they understood the model [39, 40], and most were actively involved in the decision to come [40]. These findings counter the international trend toward de-emphasising and de-valuing clinically focused TRR in favour of an emphasis on the provision of permanent housing and the mobilisation of relevant support around the consumer [6,7,8]. However, the lack of follow-up qualitative and quantitative research examining the associated short- and long-term outcomes for Community Rehabilitation Units remains problematic. There are significant risks associated with increased investment and adaptation of service models that remain largely untested.

Limitations

This review deliberately focused on Community Rehabilitation Units for people affected by severe and persisting mental illness in the Australian context. The review did not consider other types of accommodation and support that may be provided to this group, including substance use rehabilitation, non-clinical psychosocial rehabilitation services delivered by non-government organisations, and non-rehabilitation focussed supported accommodation. While these alternative residential services are outside the scope of the present review, a comprehensive understanding of the service array is critical for answering the complex questions of what works for whom, under what circumstances, and why.

The two defined service types (C-BRC and TRR) reflect changes in the approach to these services over time, rather than two distinct types that are currently operating. This limits the utility of the C-BRC type to efforts directed towards understanding historical aspects of care.

While the process of pooling service user data facilitated statistical comparison between the C-BRC and TRR types, there are several limitations associated with this approach. At least partial overlap of consumer characteristic data is anticipated due to the combination of cross-sectional and service commencement data covering overlapping time periods. Additionally, the use of cross sectional data may create bias towards more severely impaired consumers who received longer durations of residential care.

Significant gaps and methodological limitations in the literature were identified, particularly with regards to qualitative research for C-BRC services and quantitative research for TRR services. There were no randomised controlled trials, and naturalistic observational designs predominated. Given the socially complex nature of these services the absence of studies involving randomisation, blinding and controls was anticipated. Moreover, there are ethical and practical barriers to attempting randomized controlled trials of such services [41].

Conclusions

Community Rehabilitation Units in Australia fulfilled their original purpose of supporting de-institutionalised consumers to avoid hospitalisation. However, the focus of these units has shifted to the provision of transitional recovery-oriented care since the early 2000s. The profile of consumers currently accessing these services differs significantly from the original cohort. Although there is qualitative evidence to suggest that consumers value the support provided, there is no methodologically sound research quantifying the outcomes achieved. Given the ongoing and increasing investment in these services in the Australian context, there is an urgent need for high-quality research to examine the efficiency and effectiveness of these services. Such an evidence-base would be invaluable to informing policy decisions regarding the allocation of funding within the mental health service array.

Abbreviations

- ATSI:

-

Persons identifying as being aboriginal or torres strait islander

- C-BRC:

-

Community-based residential care

- CCU:

-

Community Care Unit

- CR:

-

Community residences

- CRC:

-

Community Rehabilitation Centre

- HH:

-

Hawthorn House

- NIH:

-

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute

- SPMI:

-

Severe and persisting mental illness

- STAX-SA:

-

Simple taxonomy for supported accommodation

- TRR:

-

Transitional residential rehabilitation

References

Meehan T, Stedman T, Parker S, Curtis B, Jones D. Comparing clinical and demographic characteristics of people with mental illness in hospital- and community-based residential rehabilitation units in Queensland. Aust Health Rev. 2017;41(2):139–43.

Killaspy H, Marston L, Omar RZ, Green N, Harrison I, Lean M, Holloway F, Craig T, Leavey G, King M. Service quality and clinical outcomes: an example from mental health rehabilitation services in England. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(1):28–34.

Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Flaxman AD, Johns N, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1575–86.

Charlson FJ, Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Diminic S, Stockings E, Scott JG, McGrath JJ, Whiteford HA. Global epidemiology and burden of schizophrenia: findings from the global burden of disease study 2016. Schizophr Bull. 2018.

Chopra P, Harvey C, Herrman H. Continuing accommodation and support needs of long-term patients with severe mental illness in the era of community care. Curr Psychiatr Rev. 2011;7(1):67–83.

Pratt CW, Gill KJ, Barrett NM, Roberts MM. Psychiatric rehabilitation. 3rd ed. San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press; 2014.

Corrigan PW, Mueser KT. Principles and Practice of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Second Edition : An Empirical Approach. New York: Guilford Publications; 2016.

Barbato A, Agnetti G, D'Avanzo B, Frova M, Guerrini A, Tettamanti M. Outcome of community-based rehabilitation program for people with mental illness who are considered difficult to treat. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44(6):775–83.

Parker S, Siskind D, Harris M. Community based residential mental health services: what do we need to know? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49(1):86–7.

Parker S, Dark F, Newman E, Korman N, Meurk C, Siskind D, Harris M. Longitudinal comparative evaluation of the equivalence of an integrated peer-support and clinical staffing model for residential mental health rehabilitation: a mixed methods protocol incorporating multiple stakeholder perspectives. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:179.

Tsemberis S. Houding first: ending homelessness, promoting recovery, and reducing costs. In: Ellen I, O'Flaherty B, editors. How to House the Homeless. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2010. p. 37.

Barnett K, Guiver N, Cheok F. Evaluation of the three Community Rehabilitation Centres: Final Report, presented to SA Health. Adelaide: Australian Institute for Social Research; 2011.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Open Med. 2009;3(3):e123–30.

Parker, S, Siskind, D, Harris, M, Hopkins, G. Systematic review of service models and evidence relating to the clinically operated community-based residential mental health rehabilitation for adults with schizophrenia and related disorders in Australia [https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=97326]. Accessed 03 July 2018.

Trauer T, Farhall J, Newton R, Cheung P. From long-stay psychiatric hospital to community care unit: evaluation at 1 year. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36(8):416–9.

Department of Human Services. Community Care (CCU) and secure extended care units (SECU). Program management circular. In: Division MHBMHaACS, editor. . Victoria: Victorian Government; 2007.

Greenhalgh T, Peacock R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. BMJ. 2005;331(7524):1064–5.

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Study Quality Assessment Tools [https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools]. Accessed 15 Jan 2019.

Critical Appraisal Skills Program. CASP Checklists [https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/]. Accessed 15 Jan 2019.

Siskind D, Harris M, Pirkis J, Whiteford H. A domains-based taxonomy of supported accommodation for people with severe and persistent mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(6):875–94.

McDonald JH. Handbook of Biological Statistics. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Sparky House Publishing; 2014.

Kim HY. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: chi-squared test and Fisher's exact test. Restor Dent Endod. 2017;42(2):152–5.

Hobbs C, Newton L, Tennant C, Rosen A, Tribe K. Deinstitutionalization for long-term mental illness: a 6-year evaluation. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2002;36(1):60–6.

Chopra P, Herrman HE. The long-term outcomes and unmet needs of a cohort of former long-stay patients in Melbourne, Australia. Community Ment Health J. 2011;47(5):531–41.

Hamden A, Newton R, McCauley-Elsom K, Cross W. Is deinstitutionalization working in our community? Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2011;20(4):274–83.

Trauer T. Symptom severity and personal functioning among patients with schizophrenia discharged from long-term hospital care into the community. Community Ment Health J. 2001;37(2):145–55.

Farhall J, Trauer T, Newton R, Cheung P. Community Care Units Evaluation Project: One year report. Melbourne: Victorian Government; 1999.

Gerrand V, Bloch S, Smith J, Goding M, Castle D. Reforming mental health care in Victoria: a decade later. Australas Psychiatry. 2007;15(3):181–4.

Parker S, Dark F, Vilic G, McCann K, O'Sullivan R, Doyle C, Lendich B. Integrated staffing model for residential mental health rehabilitation. Ment Health Soc Incl. 2016;20(2):92–100.

McKenna B, Oakes J, Fourniotis N, Toomey N, Furness T. Recovery-oriented mental Health practice in a community care unit: an exploratory study. J Forensic Nurs. 2016;12(4):167–75.

Barnett K, Guiver N, Cheok F. Evaluation of the three community rehabilitation Centres: FINAL REPORT. In: Health S, editor. . South Australia: SA Health; 2011.

Saraf S, Newton R. Care or recovery? Redefining residential rehabilitation. Australas Psychiatry. 2017;25(2):161–3.

Smith G, Williams T, Lefay L. Evaluating the Hawthorn House Rehabilitation Service. Department of Health: Perth; 2009.

Parker S, Siskind D, Dark F. Thoughts on ‘Redefining residential rehabilitation in Australia. Australas Psychiatry. 2017;25(4):414.

Bown MJ, Sutton AJ. Quality control in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;40(5):669–77.

McPherson P, Krotofil J, Killaspy H. What works? Toward a new classification system for mental Health supported accommodation services: the simple taxonomy for supported accommodation (STAX-SA). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(2):E190.

Allison S, Bastiampillai T, Goldney R. Acute versus sub-acute care beds: should Australia invest in community beds at the expense of hospital beds? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48(10):952–4.

National Mental Health Commission. Report of the National Review of Mental Health Programmes. and Services: Contributing lives, thriving communities - Volume 1 Strategic Directions Practical Solutions 1–2 years, vol. 1. Sydney : Australian Government, National Mental Health Commission; 2014. [http://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/media/119905/Vol%201%20-%20Main%20Paper%20-%20Final.pdf]. Accessed 15 Jan 2019.

Parker S, Meurk C, Newman E, Fletcher C, Swinson I, Dark F. Understanding consumers’ initial expectations of community-based residential mental health rehabilitation in the context of past experiences of care: a mixed-methods pragmatic grounded theory analysis. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2018;27(6):1650–60.

Parker S, Dark F, Newman E, Hanley D, McKinlay W, Meurk C. Consumers’ understanding and expectations of a community-based recovery-oriented mental health rehabilitation unit: a pragmatic grounded theory analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2017:1–10.

Wolff N. Using randomized controlled trials to evaluate socially complex services: problems, challenges and recommendations. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2000;3(2):97–109.

Newton L, Rosen A, Tennant C, Hobbs C, Lapsley HM, Tribe K. Deinstitutionalisation for long-term mental illness: an ethnographic study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(3):484–90.

Hobbs C, Tennant C, Rosen A, Newton L, Lapsley HM, Tribe K, Brown JE. Deinstitutionalisation for long-term mental illness: a 2-year clinical evaluation. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(3):476–83.

Farhall J, Trauer T, Newton R, Cheung P. Minimizing adverse effects on patients of involuntary relocation from long-stay wards to community residences. Psychiatr Ser. 2003;54(7):1022–7.

Parker S, Dark F, Newman E, Korman N, Rasmussen Z, Meurk C. Reality of working in a community-based, recovery-oriented mental health rehabilitation unit: a pragmatic grounded theory analysis. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2017;26(4):355–65.

SA HEALTH MHU. Community Mental Health Services Service Model. South Australia: Community Recovery Centres; 2010.

SA HEALTH, editor. Community recovery Centre - model of service: SA HEALTH MHU; 2010.

Meurk C, Parker S, Newman E, Dark F. Staff expectations of an integrated model of residential rehabilitation for people with severe and persisting mental illness: a pragmatic grounded theory analysis. Brisbane: University of Queensland. p. 2018.

Queensland Mental Health Benchmarking Unit. Community Care Units and Extended Treatment and Rehabilitation Mental Health Services: Benchmarking Report 2013 - Queensland Mental Health Benchmarking Unit. Wacol: Queensland Mental Health Benchmarking Unit; 2013.

Queensland Mental Health Benchmarking Unit. Multi-site benchmarking of Community Care Units and Extended Treatment & Rehabilitation Mental Health Services - Comparative benchmarking report 2011 - Queensland Mental Health Benchmarking Unit. Wacol: Queensland Mental Health Benchmarking Unit; 2011.

Jones D, Neuendorf K, Denkel N. Multi-site benchmarking of Extended Treatment & Rehabilitation and Dual Diagnosis Inpatient Mental Health Services. Wacol: Queensland Mental Health Benchmarking Unit; 2009.

Davidson F, Jones D, Neuendorf K. Multi-site benchmarking of Extended Treatment & Rehabilitation and Dual Diagnosis Inpatient Mental Health Services - Benchmarking report (2007). Wacol: Queensland Mental Health Benchmarking Unit; 2007.

Meehan T, Neuendorf K. Multi-site benchmarking of Extended Treatment & Rehabilitation and Dual Diagnosis Services - Benchmarking Report (2005). Wacol: Service Evaluation and Research Unit, The Park Centre for Mental Health, Brisbane; 2005.

Queensland Mental Health Benchmarking Unit. Community Care Units: Benchmarking report 2015 - Queensland Mental Health Benchmarking Unit. Wacol: Mental Health, Alcohol and Other Drugs Branch, Department of Health (Queensland); 2015.

Queensland Mental Health Benchmarking Unit (QMHBU): Community Care Units (CCU) Benchmarking Report 2017. 2017.

Rosen A, Trauer T, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Parker G. Development of a brief form of the life skills profile: the LSP-20. Australas Psychiatry. 2001;35(5):677–83.

Wing JK, Beevor AS, Curtis RH, Park SB, Hadden S, Burns A. Health of the nation outcome scales (HoNOS). Research and development. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:11.

Munro J, Palmada M, Russell A, Taylor P, Heir B, McKay J, Lloyd C. Queensland extended care services for people with severe mental illness and the role of occupational therapy. Aust Occup Ther J. 2007;54:257–65.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No specific funding was obtained in support of the completion of this study.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DS Advisory support to SP including guidance around the study design and process, and registration. Review of iterative drafts of the manuscript. Quality assessment of relevant papers where SP was a listed author. FD Content expertise in relation to Community Rehabilitation Units. Involvement in study design and review of iterative drafts of the manuscript. GH Active involvement in study selection, quality appraisal and data extraction. Collaborative drafting of the initial manuscript, including identification of key findings and manuscript structure. Review of iterative manuscript drafts. GM Statistical support in the management and presentation of quantitative data. Review of iterative manuscript drafts. HW Advisory support to SP, including guidance around the initial concept and scope, and methodology. Review of iterative manuscript drafts. MH Advisory support to SP including guidance around the study design and process, preparation and presentation of data, and interpretation of findings. Review of iterative drafts of the manuscript. SP Coordination of the research team. Contribution to study concept and design. Conduct of systematic review in collaboration with GH including study selection, quality appraisal and data extraction. Collaborative drafting of the initial manuscript, including identification of key findings and manuscript structure. Re-drafting manuscript in response to feedback from members of the team. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

DS, FD, GH and SP are employees of MSAMHS, a public mental health service in Queensland, Australia which operates three Community Care Units.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Literature Search Strategy. (PDF 403 kb)

Additional file 2:

Quality appraisal. (PDF 156 kb)

Additional file 3:

Service types and models. (PDF 99 kb)

Additional file 4:

Consumer characteristics. (PDF 457 kb)

Additional file 5:

Included research relating to community-based and clinically operated residential rehabilitation for people affected by schizophrenia and related disorders in Australia. (PDF 559 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Parker, S., Hopkins, G., Siskind, D. et al. A systematic review of service models and evidence relating to the clinically operated community-based residential mental health rehabilitation for adults with severe and persisting mental illness in Australia. BMC Psychiatry 19, 55 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2019-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2019-5