Abstract

Background

Although Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) is an evidence-based psychosocial treatment for borderline personality disorder (BPD), the demand for it exceeds available resources. The commonly researched 12-month version of DBT is lengthy; this can pose a barrier to its adoption in many health care settings. Further, there are no data on the optimal length of psychotherapy for BPD. The aim of this study is to examine the clinical and cost-effectiveness of 6 versus 12 months of DBT for chronically suicidal individuals with BPD. A second aim of this study is to determine which patients are as likely to benefit from shorter treatment as from longer treatment.

Methods/Design

Powered for non-inferiority testing, this two-site single-blind trial involves the random assignment of 240 patients diagnosed with BPD to 6 or 12 months of standard DBT. The primary outcome is the frequency of suicidal or non-suicidal self-injurious episodes. Secondary outcomes include healthcare utilization, psychiatric and emotional symptoms, general and social functioning, and health status. Cost-effectiveness outcomes will include the cost of providing each treatment as well as health care and societal costs (e.g., missed work days and lost productivity). Assessments are scheduled at pretreatment and at 3-month intervals until 24 months.

Discussion

This is the first study to directly examine the dose-effect of psychotherapy for chronically suicidal individuals diagnosed with BPD. Examining both clinical and cost effectiveness in 6 versus 12 months of DBT will produce answers to the question of how much treatment is good enough. Information from this study will help to guide decisions about the allocation of scarce treatment resources and recommendations about the benefits of briefer treatment.

Trial registration

NCT02387736. Registered February 20, 2015.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a serious and debilitating psychiatric condition affecting 1 to 6% of the population [1, 2]. Of particular concern, BPD is associated with exceedingly high rates (80%) of self-injury [3] and suicide-related mortality (9–33%) [4, 5] comprising 28–47% of all mortalities by suicide [6,7,8]. Notably, individuals with BPD are overrepresented in primary care [9] and mental health care settings [10, 11]. As such, BPD is a serious health concern that heavily taxes the mental health system [12,13,14]. Furthermore, individuals with BPD frequently have difficulties with social and occupational functioning [15], and disproportionately utilize social assistance [16]. Together, these factors make BPD a particularly costly disorder to treat [17,18,19].

Among the psychosocial treatments showing efficacy for BPD [20,21,22,23], dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT), a comprehensive cognitive behavioural treatment, has accrued the most empirical support [24]. DBT involves weekly hour-long individual therapy, weekly group skills training (typically 2–2.5 h), between-session telephone consultation as needed to coach the patient in the use of behavioural skills (typically by phone or other communication media), and weekly therapist consultation team meetings designed to support, motivate, and enhance the skills of therapists [25]. Several randomized controlled trials have evaluated a standard 12-month version of DBT. Results support the effectiveness of DBT relative to treatment as usual for reducing self-injurious behaviours and treatment dropout among BPD patients [26,27,28]. As well, one trial demonstrated the superiority of DBT to non-behavioural treatment by experts in terms of reducing self-injurious behaviours, treatment dropouts, and hospitalizations among suicidal patients with BPD [29]. In addition, DBT has shown comparable efficacy to other structured BPD-specific treatments [21, 30]. Recent meta-analyses demonstrate that DBT is associated with medium to large effects in terms of improvements in self-injurious behaviours [31, 32], anger, and overall mental health [31]. Standard DBT is lengthy and resource intensive [33] but it is associated with reduced overall cost burden associated with BPD [34,35,36]. Due to its robust support, international guidelines for effective psychosocial treatment have identified DBT as a treatment for BPD that has accumulated the most evidence, particularly for individuals with self-injurious behaviours [37, 38].

Although DBT is effective [31, 32], and cost-effective [34, 36], the treatment remains lengthy (often 12 months or longer) and comprehensive, requiring substantial resources to implement. Public health care systems often lack the resources to develop and sustain DBT programs [39, 40]; thus, the vast majority of individuals with BPD are left without access to evidence-based treatments. Furthermore, private insurance often does not fully cover comprehensive DBT [41]. Accordingly, many treatment centres implement idiosyncratic, truncated versions of standard DBT [42,43,44] that do not have the empirical support of standard 1-year DBT [45]. The potential cost-effectiveness and ease of delivery for brief DBT (defined here as 6-months) would allow effective treatment to reach larger numbers of patients. Consequently, clinicians and researchers have identified the need for brief, effective treatments for BPD as an urgent health priority [43].

Despite the dearth of research on the optimal duration of specialized treatments for BPD such as DBT, there is some evidence indicating that brief forms of DBT are effective. Only one randomized controlled trial (RCT) to date has examined 6-months of standard DBT [33], focusing on female veterans with BPD. Compared with 6-months of treatment as usual, patients who received 6-months of DBT exhibited greater improvements in suicidal ideation, hopelessness, depression, and anger expression [33]. This study, however, was relatively small (n = 10 per arm) and did not compare 6-months of DBT with a longer course of DBT. More recently, findings from a larger (n = 45 per arm) non-randomized trial suggested that 6-months of DBT for adults with BPD yielded improvements in self-harm, emergency department visits, hospitalizations, depression, anxiety, and overall functioning, relative to a treatment as usual wait list condition [36]. Similarly, a small (n = 20) uncontrolled study examined a 6-month version of standard DBT for suicidal patients with BPD, and found excellent treatment retention (95%) and significant pre- to post-treatment reductions in self-harm, suicidal ideation, depression, and hopelessness [46]. Thus, emerging data suggest that 6-month is a promising duration for a briefer course of DBT.

Despite the urgent need to identify whether briefer versions of DBT are clinically and cost effective for individuals diagnosed with BPD, research in this area is limited. First, extant studies of brief DBT have been small and underpowered. Second, there is a dearth of RCTs, making it hard to draw conclusions about the findings. Third, no studies have directly compared briefer forms of DBT with the most commonly used duration in the literature (12 months). Finally, the health economic impact of 6-months of DBT has not been evaluated. Although the direct costs of implementing 6-months of DBT will inevitably be lower compared with 12-months, the long-term costs or savings associated with 6-months of treatment require investigation.

Further, given the considerable heterogeneity among the symptoms, characteristics, and presenting problems of BPD patients, variability in treatment response is inevitable. Mean effect sizes for each group will likely over- or underestimate the response to treatment for some patients [47], and the identification of predictors of treatment response is critical to informing the effectiveness and efficiency of therapies [48]. Therefore, it is important to examine which patients do achieve superior benefits from 6-months versus 12-months of DBT.

Few studies have examined predictors of treatment outcomes for BPD patients. Although the treatments in these studies did not include standard DBT and involved acute (5-day [43]) or brief (≤5-month) adjunctive treatments [49,50,51], several patient characteristics were associated with outcome. For instance, high levels of clinical severity predicted greater improvement in BPD symptoms [49] and high levels of impulsivity and self-harm frequency [43, 50] predicted greater improvements in self-harm although it’s unclear whether these findings may be due to a regression to the mean. Additionally, co-occurring generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) predicted less improvement in self-harm and other self-destructive behaviours [50], and cluster A personality disorders predicted less improvement in self-destructive behaviours [50] and depression [51]. Furthermore, co-occurring post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and cluster C personality disorders predicted less improvement of emotion dysregulation and quality of life [50]. Taken together with the promising findings for 6-month versions of DBT in the treatment of BPD patients with high rates self-harm and impulsive behaviours, these data suggest that some BPD patients may not achieve sufficient benefits from brief treatments. Predictors of poorer response to brief DBT may include the presence of co-occurring PTSD, GAD, and cluster A or C personality disorders. Clarifying how different lengths of DBT work for subsets of patients with BPD will have a major impact on how healthcare resources may be allocated and patients triaged.

In sum, though DBT is the most empirically-supported psychosocial treatment for BPD, the 12-month version of DBT studied most often in clinical trials requires substantial resources. Currently, the optimal “dose” of treatment is unknown. The present study will fill an important gap in this research, by (1) comparing the benefits of 6-months versus 12-months of DBT in a rigorous RCT for BPD patients with chronic self-injury, (2) examining the economic impact of 6- versus 12-months of DBT, and (3) identifying patient characteristics that differentiate which individuals do and do not benefit from 6-months of DBT. With a focus on high risk individuals with BPD, such research will answer the question of whether and for whom 6-months of DBT is clinically indicated and/or economically attractive.

Methods/design

Study aims and hypotheses

Aim 1

To evaluate the clinical effectiveness of DBT-6 compared to DBT-12 for the treatment of chronically self-harming individuals with BPD. The following main hypotheses will be examined:

Hypothesis 1a: Patients in the DBT-6 arm will show equivalent reductions in the frequency and severity of self-harm across the treatment phase compared with patients in the DBT-12 arm. Hypothesis 1b: Patients in the DBT-6 arm will show equivalent reductions in the frequency and severity of self-harm across a 1-year post treatment follow-up phase, compared with patients in the DBT-12 arm.

Aim 2

To identify which subtypes of BPD patients are as likely to benefit from DBT-6 versus DBT-12.

Hypothesis 2a: Patients who present with high rates of self-harm and impulsive behaviours will have reductions in the frequency and severity of self-harm behaviours that are comparable in the DBT-6 arm and the DBT-12 arm, over the course of both the treatment phase and the 1-year post treatment follow-up.

Hypothesis 2b: Patients with co-occurring post-traumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, or cluster A or C personality disorders will exhibit lesser reductions in the frequency and severity of self-harm behaviours in the DBT-6 arm compared to the DBT-12 arm, over the course of both the treatment phase and the 1-year post treatment follow-up. In other words, a subtype by duration interaction is expected.

Study design

This is a two-site, single-blind, two-arm randomized controlled trial. To date, study enrollment is complete. Two-hundred and forty participants were randomly assigned to receive either 12-months of DBT (DBT-12) or 6-months of DBT (DBT-6). Follow-up assessments are occurring every 3 months, with the final assessment occurring at 24-months.

Study setting and recruitment

The study is being conducted at two sites, the BPD Clinic at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) in Toronto, Ontario, and the Personality and Emotion Research Laboratory in conjunction with the DBT Centre in Vancouver, British Columbia. Of the 240 participants, 160 were enrolled in Toronto and another 80 participants were enrolled at the Vancouver site. Participants were drawn from existing treatment or research wait-lists at the respective sites, through advertisements at hospitals, universities, and health service centres, and via word of mouth referrals from clinicians seeing potentially appropriate patients.

Prospective participants were pre-screened on the phone by a research assistant. The research assistant described the study, explained the screening process, and informed potential participants that if found eligible, they would be randomized to either 12 or 6-months of DBT. If the individual was interested, the research assistant conducted a telephone screen to gather information pertinent to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Individuals who met eligibility criteria were invited to attend an in-person assessment session to determine their eligibility. The in-person assessment was conducted by trained study assessors, who were responsible for obtaining prospective participant consent to participate in the trial. These assessors were also responsible for administering structured interviews and tests that focused on inclusion/exclusion criteria. If the participant was deemed eligible for participation, the interview continued to include structured diagnostic interviewing of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV Axis I and II disorders. The in-person assessment, conducted over the course of 2 days included laboratory measures of attention and implicit associations of emotion regulation with self-harm and the completion of self-report questionnaires. All procedures were approved by CAMH and SFU research ethics boards.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Individuals aged 18–65 were eligible to participate if they (a) met DSM-IV criteria for BPD based on the International Personality Disorders Examination (IPDE), (b) exhibited recent and chronic self-injurious behaviours, operationalized as at least 2 episodes of self-injury or suicide attempts in the past 5 years, including at least 1 episode in the past 8 weeks, (c) are proficient in English, (d) consent to study participation, (e) have not received more than 8 weeks of standard DBT in the past year, and (f) have either Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) coverage or BC Medical Services Plan (MSP) health insurance for 1 year or more.

Exclusion criteria

Participants were excluded from the study if they (a) met the criteria for a specific psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder I, or dementia, based on the DSM-IV [52], (b) have an estimated IQ less than or equal to 70, (c) have a chronic or serious physical health problem expected to require hospitalization within the next year (e.g., cancer), or (d) have plans to move out of the province in the next 2 years.

Assessment of inclusion/exclusion criteria

Assessors masked to condition assignment and calibrated with a gold-standard assessor on study instruments are assessing participants’ symptoms of DSM-IV diagnoses. BPD criteria are being assessed with the International Personality Disorder Examination [53], a well-established semi-structured interview used by the World Health Organization. Other personality disorders are being assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV, Axis II (SCID-II [54]). DSM-IV Axis I disorders will be assessed with the SCID-I (for Axis I disorders), Patient Version ([55]). Cognitive functioning is being assessed with the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR) [56], a brief measure of verbal intelligence.

Randomization

Individuals who provided informed consent and were eligible were informed of the treatment arm to which they were assigned by each site’s coordinator after the baseline assessment. The allocation scheme was developed in order to maintain blindness and random assignment, while minimizing wait-list time and avoiding unfilled slots in either treatment arm. The allocation scheme used variable block sizes with permutations of 4 and was generated by the statistician. A research assistant then put the allocation scheme into a series of consecutively numbered white, opaque, sealed envelopes (numbered 1 to n, where n is the study site sample size). When there was a minimum of 1 opening per each of the 2 treatment conditions at either treatment site, the research coordinator opened the next randomization envelope, which revealed participant assignment to either 6-months (DBT-6) or 12-months (DBT-12) of DBT. Randomization was conducted independently at each site.

Interventions

We are comparing two interventions: DBT 12-months [25, 57, 58] and DBT 6-months.

DBT is a comprehensive therapy that blends acceptance-based techniques derived from the Zen tradition [25, 57,58,59] with strategies from traditional cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), including problem-solving, behavioural analysis, contingency management, and skills training techniques. DBT consisted of: 1) weekly 1-h individual therapy session, 2) a 2-hour weekly skills training group, 3) access to 24 h/7 days a week telephone consultation and, 4) weekly therapist consultation meetings.

Comparison of DBT-6 and DBT-12

The treatment conditions are comparable on all factors except for length of treatment. Both treatment conditions involve all four treatment components, and an equal number of treatment hours per week. In order to control for hours of therapy received, participants are expected to not engage in other primary psychosocial treatments. Further, to control for possible confounding effects of therapist characteristics, therapists across the 2 conditions are matched on a number of factors including expertise, training in DBT, and availability of supervision.

Treatment dropouts

Consistent with the DBT treatment protocol, participants who fail to attend four consecutive scheduled individual or group sessions are discontinued from treatment and will be considered dropouts.

Therapists

Therapists at both sites include doctoral and master’s level therapists who have attended formal DBT basic and advanced-level workshops, with a minimum of 2 years of supervised experience in DBT and treating BPD patients. Senior therapists (SM, JK, AC) who are certified DBT practitioners with the Linehan Board of Certification and Accreditation are supervising the therapists and leading supervision and therapist consultation meetings at each site.

Treatment adherence

Therapist competence and treatment delivery is being monitored via therapist adherence ratings, individual supervision (weekly for students and unregistered clinicians who require more monitoring), and weekly DBT consultation team meetings. All individual and group therapy sessions are being videotaped, and therapist adherence is being assessed using the University of Washington DBT Adherence Rating Scale [60]. This scale provides scores on a scale of 0 to 5 across a range of DBT strategies [25, 57,58,59], with global adherence scores of ≥4.0 indicating adherence to DBT. Psychology graduate student coders masked to treatment assignment and trained to an acceptable level of reliability at the University of Washington in Seattle, WA are independently rating a random selection of 5% of sessions from each therapist-patient dyad, with an equal proportion of sessions coded in the pre-treatment orientation (first 4 weeks), early, middle, and late stages of treatment. As well, 5% of all group sessions are being evaluated for adherence.

Assessments

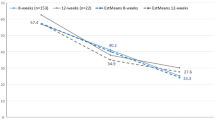

Over the course of the study (i.e., 6 or 12 month treatment and follow-up phase), participants are being assessed at 9 time points: pretreatment, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21 and 24 months. Outcome measures are the same as those used in previous RCTs of DBT [27,28,29,30, 61, 62], allowing for comparability with previous outcomes. The measures are described below, and Table 1 summarizes the schedule of measures.

Clinical outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is the frequency and severity of self-injurious episodes, measured by the Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview (SASII [63]). The SASII is a semi-structured interview that measures frequency and medical severity of self-injury and suicide attempts and is administered by trained assessors at all assessment points to measure self-injury over the previous 3-month assessment interval.

Secondary outcomes/predictors of response

Secondary outcomes and predictors of response measures assess a range of characteristics and suicidal and self-harm behaviours, health-related outcomes, including hospitalization, emergency room visits, psychiatric symptoms, social functioning, general functioning, and treatment retention. Characteristics of self-injury (including suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury), including frequency, medical severity, intent to die, lethality, and precipitants of self-injury, are being assessed with the Lifetime Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Count (L-SASI) (Lifetime Parasuicide History; Linehan & Comtois, unpublished 1996). See Table 1 for schedule of measures. Healthcare utilization is being measured with the Treatment History Interview − 2 (THI-2) (THI; Linehan & Heard, unpublished 1987), which assesses the number and type of outpatient psychosocial treatments, number and duration of hospital admissions, frequency of emergency department visits, and medication use. Borderline personality disorder severity is being assessed using the Borderline Symptom List – 23 (BSL-23 [64, 65]), a self-report measure, assessing the severity of BPD symptoms in the past week. Impulsivity is being assessed using the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11 [66]), and depressive symptoms are being measured using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II [67]). The State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2 [68]) is being used to measure participants’ experiences and expressions of anger. The Symptom Checklist-90 Revised (SCL-90-R [69]), a widely used self-report questionnaire, is being used to measure past-week general symptom distress. Interpersonal functioning is being assessed with the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-64 (IIP-64 [70]), which assesses dysfunctional patterns in interpersonal interactions. Social functioning is being assessed with the Social Adjustment Scale-Self Report (SAS-SR [71]), which measures social adjustment. Health-related quality of life outcomes are being monitored using the EuroQol 5D-5 L (EQ-5D-5 L [72]) and the Medical Outcomes Score Short Form (SF-36 [73]), which assesses physical and mental health functioning. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT [74]) is a 10-item screening questionnaire regarding the amount and frequency of alcohol consumption, dependence on alcohol, and problems associated with alcohol use, and is being used to assess for alcohol-related problems. The Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST [75]), a 28-item self-report questionnaire widely used in treatment evaluation research, is being used to assess problems associated with drug misuse. The Inventory of Statements About Self-Injury (ISAS [76]), is a self-report questionnaire that measures non-suicidal self-harm behaviors. Suicidal intentions are assessed using the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSS [77]), a self-report questionnaire consisting of 19 items. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5 [78]) is a 20-item self-report measure used to assess symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Emotion dysregulation is measured using the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS [79]), a 36-item, self-report. Mindfulness is being assessed with the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills (KIMS [80]) self-report questionnaire. The Dialectical Behavior Therapy-Ways of Coping Checklist (DBT-WCCL [81]) is used to assess thoughts and behaviors related to coping strategies during stressful events.

The following other measures are administered to assess predictors of response. Demographic information will be collected with the Demographic Data Schedule (DDS [82]) at baseline. The NEO-Five Factor Inventory, short form (NEO-SF [83]), a widely used personality measure, is being used to assess personality dimensions (i.e., neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) and is collected at baseline. The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF [84]), a self-report measure of childhood abuse and neglect is being collected at 3-months and the Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire (CEQ [85]) is being collected at baseline. The Working Alliance Inventory-Short Form (WAI-S [86]), therapist and client version are collected after each of the first 4 treatment sessions and at 3 and 6-months.

Finally, the Reasons for Early Termination from Treatment Questionnaire (RET-C [87]) is administered to evaluate reasons for premature termination and is administered to participants who drop out of treatment.

Participants are being compensated at a rate of $10 Canadian dollars (CDN) per hour for the completion of these study measures.

Health economic outcomes

One objective of this research is to compare the cost of DBT-6 vs DBT-12. Costs include direct treatment cost, health services cost (e.g., hospitalization, emergency room visits, day surgery or procedure, physician visits, medications), productivity costs, and law enforcement and related cost. The cost analysis will be based on the healthcare resources data obtained from the THI-2 in the trial and with participant consent, imported to and linked with federal and provincial administrative databases (for Ontario, the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; for British Columbia, B.C. Population Health; in addition to the Canadian Institute for Health Information). Additionally, using established guidelines for cost-effectiveness research [88], data on therapist and consultation team time devoted to research participants (e.g., in meetings, individual and group sessions, between-session communication) are being collected and used to calculate per patient cost of service provision based on expected service provider costs (e.g., salary, benefits).

Genetic data

An amendment to the original protocol for the addition of a genetic component to the study and collection of saliva samples was approved in September, 2015. A separate consent form was developed for this data collection. Participants’ who provide consent to the genetic study are required to provide five small saliva samples (about half a teaspoon each) to the research team at the following time points: a) at baseline, b) at 6-months, c) 1 year, d) one-and-a-half years, and e) 2 years into the study. These time-based samples will be used specifically for epigenetic comparisons before, during and after DBT treatment. Patients are receiving $20 remuneration per saliva sample.

Data collection for the study began in February, 2015 and is expected to be complete by July, 2019.

Interview outcome data will be double data-entered. Other data collected via an electronic encrypted data management system are not double data entered. Data is stored on an encrypted server. Study outcome data is stored in a locked cabinet in accordance with ethical guidelines governing the management of data. All study data collected will be maintained for 25 years before being destroyed.

Masking of treatment allocation

Several methods will be used to conceal treatment allocation of participants and protect against sources of bias. Therapists will not function as assessors, and vice versa. Study assessors are masked to participants’ treatment assignment with the exception of assessors who administer the Treatment History Interview-2 (THI-2) (THI; Linehan & Heard, unpublished 1987). This measure includes questions about the treatment received and may disclose the condition to which the participant is assigned, therefore an RA who is not masked to the participant’s treatment assignment will conduct this interview. Third, both therapists and assessors will consistently be reminded of the study masking requirements, and discussions about clients between therapists and assessors will be discouraged.

Sample size and power analysis

The study was designed to test whether DBT-6 is not inferior to DBT-12 (an established treatment). The estimate of the sample size required for a non-inferiority test was based on the effect sizes from prior DBT RCTs [30, 62]. Post-treatment suicide and self-harm estimates over 4 months were 2.26 episodes for DBT-6 and 0.73 for DBT-12 (SDpooled = 4). We expected no significant differences between the DBT-6 and DBT-12 conditions in terms of reductions in the frequency and severity of self-injury episodes at 1 year. We therefore defined our delta, the clinically significant range of indifference for our non-inferiority trial, as a difference in outcomes of 1.53 (SD = .04) episodes in the frequency of self-harm episodes at post-treatment. To achieve this maximum of 1.53 or less in the difference of self-injury rates with adequate power (α = .05; 1 - β = .80), 85 participants per group are required to show non-inferiority of treatment. Allowing for a 30% dropout rate, we will recruit 120 participants per group. The sample size calculation also addresses the necessary power for secondary analyses, given that the sample size required for null hypothesis significance testing is typically less than those required for non-inferiority [89].

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics

We will examine rates of ineligibility. Demographic and clinical characteristics will be summarized using descriptive statistics.

Primary analyses

Comparison of DBT-6 versus DBT-12

Analyses will be conducted at the end of treatment and at the end of follow-up. No interim analyses are planned. The outcome analyses will be conducted on an intention-to-treat basis. The primary outcomes, frequency and severity of suicide and self-harm behaviours, are both expected to have a skewed distribution. The count nature of the self-injury frequency variable, as well as the self-injury severity ratings, are integers bounded by zero. As well, given the dependencies of the observations over time and individual variability, our primary analyses will employ a multilevel random effects Poisson growth curve model. The occasion level random effects will capture secondary over-dispersion due to the heterogeneity of observations within participant self-injury reporting [88, 90]. These random effects will follow a log-normal distribution [91], and will reduce or eliminate the disturbance effects associated with the differences between rates and forms of specific, within individual, self-harm that can bias estimates of true self-harm rates.

Specific tests of our primary hypotheses (non-inferiority tests of equivalence and post hoc comparisons of difference) will be model-based [92] using contrasting means and regression coefficients. Evaluation of model fit will be provided by statistical indices including Akaike’s Information Criteria (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) and likelihood ratio tests. To perform the comparison of self-injury outcomes at post-treatment (our primary research interest), 1-sided non-inferiority t-tests of the marginal means will be performed. If missing data are at moderate levels or are related to a specific set of covariates or outcome, we will compare multiple imputation [93], growth curve analysis [94], and instrumental variables analysis [95] since no one technique is demonstrably superior [96]. We will also examine differences in sites and therapist characteristics that may be evidenced in treatment outcomes.

Health economic analyses

We will compare the cost of DBT-6 vs DBT-12 from the perspective of the public healthcare payer. The output will be the incremental cost of DBT-6 compared to DBT-12. We will analyze the total cost as a dependent variable, using a regression model to estimate the difference in expected healthcare cost between the two groups. The intervention will be the primary independent variable and the regression model will adjust for potential confounding variables. In theory, an ordinary least squares model produces unbiased estimates even if the data are skewed; however, additional estimation methods (e.g., generalized linear models) and different uncertainty methods (e.g., parametric and non-parametric bootstrapping) will be explored to facilitate investigation of the impact of various cost assumptions [97,98,99].

Additionally, as a secondary economic analysis, we will explore the economic evaluation using the net benefit regression framework [100]. The outcome will be the incremental net benefit from DBT-6 for the intervention group compared to the standard DBT-12 group. We will also estimate the incremental cost per one self-injury episode avoided and the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained, derived from the SF-36 and EQ-5D-5 L data. To estimate QALYs gained, we will convert SF-36 and EQ-5D-5 L data collected in the trial to utility scores using a validated algorithm [101,102,103]. The QALY is the gold standard measure of effectiveness recommended for economic evaluation and allows for a more global measure of the impact of a clinical intervention. Calculating QALYs requires the combination of health-related quality of life measures with data on health state duration. The EQ-5D-5 L has been used to evaluate the quality of life of patients with schizophrenia [104] and depression [105]; however, recently its validity in BPD studies has been questioned, so the SF-36 will be used for comparison in a sensitivity analysis. Statistical uncertainty will be characterized using a 95% confidence interval and a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC) [106].

Attrition and treatment implementation

We will examine rates of treatment completion and attrition across both groups. We will conduct survival analyses to examine differences in the timing of treatment dropouts. In addition, we will compare rates of use of psychotropic medications and other adjunctive treatments at baseline and across both treatments. Treatment adherence ratings across both treatment arms will be evaluated. We also will examine potential site differences between the CAMH and SFU sites in terms of participant characteristics, and attrition. We will also examine potential therapist effects on treatment implementation and dropout rates.

Secondary analysis

Analyses of subtypes of BPD patients likely to benefit from DBT-6 versus DBT-12

Analyses related to predictors of treatment response will involve growth curve modeling, with covariates, with the two arms using both linear and over-dispersed Poisson hierarchical models. The effects of impulsivity and the rates of self-injury will be managed by person centering the variables. Growth curve models will be used to estimate the trajectories of the 4 diagnostic groups that are expected to moderate treatment response (PTSD, GAD, Cluster A, and Cluster C), but without the inclusion of covariates, provided they are not needed. Each diagnostic category will be estimated independently within a single model. The tests of both slopes and marginal effects will be carried out post-estimation, and will involve pair-wise multiple comparisons with alpha levels that are Holm’s Sequential Bonferroni adjusted.

Data safety monitoring

A data safety monitoring committee (DSMC) was established and composed of three independent researchers specializing in BPD and self-harm, cognitive behavior therapy, and biostatistics. The DSMC is responsible for monitoring the research protocol, reviewing data, assessing the safety of the trial, reporting adverse events, reviewing unanticipated problems, and monitoring protocol violations in accordance with the policies and procedures outlined in the institutional research ethics boards (REBs) at each site and in accordance with Canadian Institutes of Health Research’s (CIHR) policies and procedures concerning data and safety monitoring. The DSMC will communicate any new information to the REB at both sites over the course of the trial, and the site supervisors (SM, AC), in consultation with the research team will make the decision whether to continue, suspend, modify or stop the trial, or amend the protocol. The site supervisors (SM, AC) are responsible for monitoring and reporting serious adverse events to the DSMC. Serious adverse events are defined as any untoward medical occurrence that results in death, is life-threatening, results in persistent or significant disability/incapacity, results in a congenital anomaly/birth defect, or any important medical event that may jeopardize the health of the research participant or may require medical intervention to prevent one of the outcomes listed above. Serious adverse events involving self-harm behaviour was operationalized as very high to severe medical risk according to the SASII lethality scale.

Discussion

This will be the first rigorously controlled trial comparing two different lengths of DBT for individuals with BPD and chronic suicidal behaviour. Given the severity [4, 5] and societal costs of BPD [17,18,19], and the limited resources available for psychotherapy for BPD [39, 40], findings have the potential to significantly impact clinical practice. If 6- months of DBT produces comparable clinical outcomes to 1-year of DBT, the briefer version would be an excellent, less resource intensive alternative that could help to increase access to treatment, reducing wait times and enable more people to be treated. If 6 months of DBT became the new standard length of treatment, it would reduce the direct costs and resources compared with 1-year. If the study hypotheses are confirmed, the findings could encourage decision-makers to invest in the development of briefer programs, improving treatment accessibility.

Limitations of the study include the following: This study design does not include a control arm that could control for the passage of time. Though this would provide a more rigorous test of our study hypotheses, a third control arm (e.g., wait-list or treatment as usual) was ruled out due to ethical concerns and because of the strong evidence base demonstrating that standard DBT-12 is superior to unstructured treatment as usual controls. As well, concomitant psychotropic medications will be uncontrolled. While psychotropic utilization is a potential confound in the current study design, the restriction of medications would reduce referrals to the study and also pose a threat to external validity. Indeed, previous trials indicate that an estimated 80% of patients will be on at least one psychotropic medication [107, 108] and thus, restricting medication use would compromise the representativeness of the study sample. Therefore, by monitoring medication use throughout the trial, we believe that the current study balances the internal and external validity in a manner that is the best way to advance treatment of this population.

Study timeframe

Study enrollment began in February, 2015 and the total sample of 240 participants was completed by June, 2017. The active treatment phase is expected to be finished in June, 2018. The completion of follow-up assessments is expected in July, 2019. The dissemination of final results at international meetings is expected by the Fall of 2019. Publication of the findings is planned for 2020.

Abbreviations

- AIC:

-

Akaike’s information criteria

- AUDIT:

-

Alcohol use disorders identification test

- BDI-II:

-

Beck Depression Inventory-II

- BIC:

-

Bayesian information criteria

- BIS-II:

-

Barratt impulsiveness scale

- BPD:

-

Borderline personality disorder

- BSL-23:

-

Borderline Symptom List-23

- BSS:

-

Beck scale for suicidal ideation

- CAMH:

-

Centre for addiction and mental health

- CBT:

-

Cognitive behavioural therapy

- CDN:

-

Canadian

- CEQ:

-

Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire

- CIHR:

-

Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- Cluster A:

-

Paranoid, Schizoid, Schizotypal

- Cluster C:

-

Avoidant, Dependent; Obsessive compulsive

- CTQ-SF:

-

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form

- DAST:

-

Drug abuse screening test

- DBT:

-

Dialectical behavior therapy

- DBT-WCCL:

-

Dialectical Behavior Therapy-Ways of Coping Checklist

- DDS:

-

Demographic data schedule

- DERS:

-

Difficulties in emotion regulation scale

- DSMC:

-

Data safety monitoring committee

- DSM-IV:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition

- EQ-5D-5L:

-

EuroQol 5D-5L

- FASTER:

-

Feasibility of a shorter treatment and evaluating responses

- GAD:

-

Generalized anxiety disorder

- IIP-64:

-

Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-64

- IPDE:

-

International personality disorders examination

- IQ:

-

Intelligence quotient

- ISAS:

-

Inventory of Statements About Self-Injury

- KIMS:

-

Kentucky inventory of mindfulness skills

- L-SASI:

-

Lifetime parasuicide history

- MSP:

-

Medical services plan

- NEO-SF:

-

NEO-Five Factor Inventory, short form

- OHIP:

-

Ontario Health Insurance Plan

- PCL-5:

-

PTSD Checklist for DSM-5

- PTSD:

-

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- QALY:

-

Quality-adjusted life-year

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- RET-C:

-

Reasons for early termination from treatment questionnaire

- SASII:

-

Suicide attempt self-injury interview

- SAS-SR:

-

Social adjustment scale-self report

- SCID-I:

-

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Personality Disorders

- SCID-II:

-

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders

- SCL-90-R:

-

Symptom Checklist-90 Revised

- SF-36:

-

Medical Outcomes score short form

- SFU:

-

Simon Fraser University

- STAXI-2:

-

State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2

- THI-2:

-

Treatment History Interview − 2

- WA:

-

Washington

- WAI-S:

-

Working Alliance Inventory-Short Form

- WTAR:

-

Wechsler Test of Adult Reading

References

Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Stinson FS, Saha TD, Smith SM, Dawson DA, Pulay AJ, Pickering RP, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):533–45.

Torgersen S, Kringlen E, Cramer V. The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(6):590–6.

Gunderson JG. Borderline personality disorder: a clinical guide. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2001.

Skodol AE, Guderson JG, Pfohl B, Widiger TA, Livesley WJ, Sierver LJ. The borderline diagnosis I: psychopathology, comorbidity, and personality structure. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:936–50.

Cowdry RW, Pickar D, Davies R. Symptoms and EEG findings in the borderline syndrome. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1985;15:201–11.

Cheng AT, Mann AH, Chan KA. Personality disorder and suicide. A case-control study. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:441–6.

Lesage AD, Boyer R, Grunberg F, Vanier C. Suicide and mental disorders: a case-control study of young men. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(7):1063–8.

Black DW, Blum N, Pfohl B, Hale N. Suicidal behaviour in borderline personality disorder: prevalence, risk factors, prediction and prevention. J Personal Disord. 2004;18(3):226–39.

Gross R, Olfson M, Gameroff M, Shea S, Feder A, Fuentes M, Lantigua R, Weissman MM. Borderline personality disorder in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(1):53–60.

Ansell EB, Sanislow CA, McGlashan TH, Grilo CM. Psychosocial impairment and treatment utilization by patients with borderline personality disorder, other personality disorders, mood and anxiety disorders, and a healthy comparison group. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48:329–36.

Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Silk KR. Mental health service utilization by borderline personality disorder patients and Axis II comparison subjects followed prospectively for 6 years. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(1):28–36.

Bagge C, Stepp S, Trull T. Borderline personality disorder features and utilization of treatment over two years. J Personal Disord. 2005;19(4):420–39.

Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, Sanislow CA, Dyck IR, McGlashan TH, Shea MT, Zanarini MC, Oldham JM, Gunderson JG. Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(2):295–302.

Comtois KA, Russo J, Snowden M, Strebnik D, Ries R, Roy-Byrne P. Factors associated with high use of public mental health services by persons with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(8):1149–54.

Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Employment in borderline personality disorder. Innovations Clin Neurosci. 2012;9(9):25–9.

Zanarini MC, Jacoby RJ, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Fitzmaurice G. The 10-year course of social security disability income reported by patients with borderline personality disorder and axis II comparison subjects. J Personal Disord. 2009;23(4):346–56.

Soeteman DI, Hakkaart-van RL, Verheul R, Busschbach JJ. The economic burden of personality disorders in mental health care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(2):259–65.

van Asselt ADI, Dirksen CD, Arntz A, Severens JL. The cost of borderline personality disorder: societal cost of illness in BPD-patients. European Psychiatry. 2007;22:354–61.

Brazier J, Tumur I, Holmes M, Ferriter M, Parry G, Dent-Brown K, Paisley S. Psychological therapies including dialectical behaviour therapy for borderline personality disorder: a systematic review and preliminary economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2006;10(35):1–117.

Giesen-Bloo J, van Dyck R, Spinhoven P, van Tilburg W, Dirksen C, van Asselt T, Kremers I, Nadort M, Arntz A. Outpatient psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: randomized trial of schema-focused therapy vs transference-focused psychotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:649–58.

Clarkin JF, Levy KN, Lenzenweger MF, Kernberg OF. Evaluating three treatments for borderline personality disorder: a multiwave study. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):922–8.

Bateman A, Fonagy P. Treatment of borderline personality disorder with psychoanalytically oriented partial hospitalization: an 18-month follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:36–42.

Blum N, Pfohl B, John DS, Monahan P, Black DW. STEPPS: a cognitive-behavioral systems-based group treatment for outpatients with borderline personality disorder—a preliminary report. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(4):301–10.

Binks C, Fenton M, McCarthy L, Lee T, Adams CE, Duggan C. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD005652. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005652.

Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford press; 1993a.

Verheul R. Dialectical behaviour therapy for women with borderline personality disorder: 12-month, randomised clinical trial in the Netherlands. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:135–40.

Linehan MM, Schmidt H, Dimeff LA, Craft JC, Kanter J, Comtois KA. Dialectical behavior therapy for patients with borderline personality disorder and drug-dependence. Am J Addict. 1999;8(4):279–92.

Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, Allmon D, Heard HL. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(12):1060–4.

Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ, Heard HL, Korslund KE, Tutek DA, Reynolds SK, Lindenboim N. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(7):757–66.

McMain SF, Links PS, Gnam WH, Guimond T, Cardish RJ, Korman L, Streiner DL. A randomized trial of dialectical behavior therapy versus general psychiatric management for borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(12):1365–74.

Stoffers JM, Vollm BA, Rucker G, Timmer A, Huband N, Lieb K. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD005652.

Kliem S, Kroger C, Kosfelder J. Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis using mixed-effects modeling. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(6):936–51.

Koons CR, Robins CJ, Lindsey Tweed J, Lynch TR, Gonzalez AM, Morse JQ, Bishop GK, Butterfield MI, Bastian LA. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disorder. Behav Ther. 2001;32(2):371–90.

Wagner T, Fydrich T, Stiglmayr C, Marschall P, Salize H-J, Renneberg B, Fleßa S, Roepke S. Societal cost-of-illness in patients with borderline personality disorder one year before, during and after dialectical behavior therapy in routine outpatient care. Behav Res Ther. 2014;61:12–22.

Hall J, Caleo S, Stevenson J, Meares R. An economic analysis of psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder patients. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2001;4(1):3–8.

Pasieczny N, Connor J. The effectiveness of dialectical behaviour therapy in routine public mental health settings: an Australian controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49(1):4–10.

(UK) NCCfMH. Borderline Personality Disorder: Treatment and Management. Leicester: British Psychological Society; 2009.

Council NHaMR. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Borderline Personality Disorder. Cranberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2013.

Health NCCfM. Borderline personality disorder: treatment and management. Leicester: British Psychological Society the British Psychological Society & The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2009.

Carmel A, Rose ML, Fruzzetti AE. Barriers and solutions to implementing dialectical behavior therapy in a public behavioral health system. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Research Services. 2013;170(5):1–7.

Swenson CR, Torrey WC, Koerner K. Implementing dialectical behavior therapy. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(2):171–8.

Blackford JU, Love R. Dialectical behavior therapy group skills training in a community mental health setting: a pilot study. Int J Group Psychother. 2011;61(4):645–57.

Yen S, Johnson J, Costello E, Simpson EB. A 5-day dialectical behavior therapy partial hospital program for women with borderline personality disorder: predictors of outcome from a 3-month follow-up study. J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15(3):173–82.

Van Dijk S, Jeffrey J, Katz MR. A randomized, controlled, pilot study of dialectical behavior therapy skills in a psychoeducational group for individuals with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;145(3):386–93.

Kelly Koerner LAD, Swenson CR. Adopt or adapt? Fidelity matters. In: Koerner LADK, editor. Dialectical Behaviour Therapy in Clinical Practice Applications Across Disorders and Settings. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. p. 19–36.

Stanley B, Brodsky B, Nelson J, Dulit R. Brief dialectical behavior therapy (DBT-B) for suicidal behavior and non-suicidal self-injury. Arch Suicide Res. 2007;11:337–41.

Kernberg OF, Michels R. Borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(5):505–8.

Kazdin AE. Progression of therapy research and clinical application of treatment require better understanding of the change process. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2001;8:143–51.

Black DW, Allen J, St JD, Pfohl B, McCormick B, Blum N. Predictors of response to systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving (STEPPS) for borderline personality disorder: an exploratory study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;120(1):53–61.

Gratz KL, Dixon-Gordon KL, Tull MT. Predictors of treatment response to an adjunctive emotion regulation group therapy for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Personal Disord. 2014;5(1):97–107.

Perroud N, Uher R, Dieben K, Nicastro R, Huguelet P. Predictors of response and drop-out during intensive dialectical behavior therapy. J Personal Disord. 2010;24(5):634–50.

Association Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV). 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Press; 1994.

Loranger AW, Sartorius N, Andreoli A, Berger P, Buchheim P, Channabasavanna SM, Coid B, Dahl A, Diekstra RFW, Ferguson B, et al. The international personality disorder examination: the World Health Organization/alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health administration international pilot study of personality disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(3):215–24.

SR FMB, Gibbon M, JBW W, Benjamin L. User’s guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II). New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996.

First MBSR, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCIDI/P). New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002.

Wechsler D. Wechsler Test of Adult Reading: WTAR: Psychological Corporation; 2001.

Linehan MM. Skills training manual for treating borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993b.

Linehan MM. DBT skills training manual. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2015.

Linehan MM. DBT skills training handouts and worksheets. New York: Guilford Press; 2015.

Linehan MM, Korslund K. Dialectical behavior therapy adherence manual. Seattle: University of Washington; 2003.

Linehan MM, Dimeff LA, Reynolds SK, Comtois KA, Welch SS, Heagerty P, Kivlahan DR. Dialectical behavior therapy versus comprehensive validation therapy plus 12-step for the treatment of opioid dependent women meeting criteria for borderline personality disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;67(1):13–26.

McMain SF, Guimond T, Streiner DL, Cardish RJ, Links PS. Dialectical behavior therapy compared with general psychiatric management for borderline personality disorder: clinical outcomes and functioning over a 2-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(6):650–61.

Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Brown MZ, Heard HL, Wagner AW. Suicide attempt self-injury interview (SASII): development, reliability, and validity of a scale to assess suicide attempts and intentional self-injury. Psychol Assess. 2006;18(3):303–12.

Bohus M, Kleindienst N, Limberger MF, Stieglitz R, Domsalla M, Chapman AL, Steil R, Philipsen A, Wolf M. The short version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23): development and initial data on psychometric properties. Psychopathology. 2009;42(1):32–9.

Bohus M, Limberger MF, Frank U, Chapman AL, Kuhler T, Stieglitz RD. Psychometric properties of the borderline symptom list (BSL). Psychopathology. 2007;40(2):126–32.

Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51(6):768–74.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for Beck depression inventory II. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1996.

Spielberger CD. STAXI-2 : state-trait anger expression Inventory-2 : professional manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1999.

Derogatis LR. SCL-90-R: administration, scoring and procedures manual-II for the R(evised) version. Baltimore: Clinical Psychometric Research; 1977.

Horowitz LM, Rosenberg SE, Baer RA, Ureno G, Villasenor VS. Inventory of interpersonal problems: psychometric properties and clinical applications. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):885–92.

Tadaharu N, Kitamura T. The Social Adjustment Scale (SAS). J Ment Health. 1986;33:67–119.

Kind P. The EuroQoL instrument: an index of health-related quality of life. In: Spilker B, editor. Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials Second Edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996.

McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Lu JF, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form health survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32(1):40–66.

Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG, Organization WH: AUDIT: the alcohol use disorders identification test: guidelines for use in primary health care. 2001.

Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav. 1982;7(4):363–71.

Klonsky DE. The functions of deliberate self-injury: a review of the evidence. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27(2):226–39.

Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the scale of suicide ideation. J Consulting Clin Psychol. 1979;47:343–52.

Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, Schnurr PP. 2013. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Scale available from the National Center for PTSD at https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp. Retrieved July 6, 2018.

Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;51:936–50.

Baer RA, Smith GT, Allen KB. Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: the Kentucky inventory of mindfulness skills. Assessment. 2004;11:191–206.

Neacsiu AD, Rizvi SL, Vitaliano PP, Lynch TR, Linehan MM. The dialectical behavior therapy ways of coping checklist (DBT-WCCL): development and psychometric properties. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66(61):1–20.

Linehan MM. Demographic data schedule (DDS). Seattle: University of Washington; 1982.

Costa PT, McCrae RR. Professional manual: revised NEO personality inventory (NEP-PI-R) and NEO five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI). Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992.

Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Stokes J, Handelsman L, Medrano M, Desmond D, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse Neglect. 2003;27(2):169–90.

Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2000;31:73–86.

Horvath AO, Greenberg LS. Development and validation of the working alliance inventory. J Couns Psychol. 1989;36(2):223–333.

Early termination and the outcome of psychotherapy: Patient’s perspectives. Diss Abstr Int. 1986;46(B):2817–8.

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes: Oxford University press; 2015.

Streiner DL. Unicorns do exist: a tutorial on “proving” the null hypothesis. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48(11):756–61.

Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using Statab, Second edition: Stata press; 2008.

Clayton D, Kaldor J. Empirical Bayes estimates of age-standardized relative risks for use in disease mapping. Biometrics. 1987;43(3):671–81.

Elston DA, Moss R, Boulinier T, Arrowsmith C, Lambin X. Analysis of aggregation, a worked example: numbers of ticks on red grouse chicks. Parasitology. 2001;122(5):563–9.

Rubin D. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987.

Streiner DL. The case of the missing data: methods of dealing with drop-outs and other vagaries of research. Can J Psychiatr. 2002;47(1):68–75.

Angrist JD, Imbens GW, Rubin DB. Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. J Am Stat Assoc. 1996;91:444–72.

Kenward MG, Carpenter J. Multiple imputation: current perspectives. Stat Methods Med Res. 2007;16(3):199–218.

Briggs A, Nixon R, Dixon S, Thompson S. Parametric modelling of cost data: some simulation evidence. Health Econ. 2005;14(4):421–8.

Barber J, Thompson S. Multiple regression of cost data: use of generalised linear models. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2004;9(4):197–204.

Glick HA, Doshi JA, Sonnad SS, Polsky D. Economic evaluation in clinical trials. Oxford: OUP; 2014.

Hoch JS, Briggs AH, Willan AR. Something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue: a framework for the marriage of health econometrics and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Econ. 2002;11(5):415–30.

John E, Brazier DR, Hanmer J. Revised SF-6D scoring programmes: a summary of improvements. PRO Newsletter Online. 2008;40:14–5.

Brazier JE, Roberts J. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Med Care. 2004;42(9):851–9.

Bansback N, Tsuchiya A, Brazier J, Anis A. Canadian valuation of EQ-5D health states: preliminary value set and considerations for future valuation studies. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31115.

Bolscher J. What do we mean by quality of life and how do we measure it in patients with schizophrenia? Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 1998;2:65–71.

Bower P, Byford S, Sibbald B, Ward E, King M, Lloyd M, Gabbay M. Randomised controlled trial of non-directive counselling, cognitive-behaviour therapy, and usual general practitioner care for patients with depression. II: cost effectiveness. BMJ. 2000;321(7273):1389–92.

Hoch JS, Rockx MA, Krahn AD. Using the net benefit regression framework to construct cost-effectiveness acceptability curves: an example using data from a trial of external loop recorders versus Holter monitoring for ambulatory monitoring of “community acquired” syncope. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:68.

Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Parachini EA. A preliminary, randomized trial of fluoxetine, olanzapine, and the olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in women with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(7):903–7.

Stoffers JM, Lieb K. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder—current evidence and recent trends. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(1):534.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Canadian Institutes of Health Research for funding this ongoing study (CIHR OG 311138).

The authors would like to especially thank Michaelia Young, Sonya Varma, Cathy Labrish, and Lisa Choshino for their support in data collection and trial management.

Funding

The projected received 5-years of funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). The total funding received for the trial was $1,459,322.00 CDN. The project was awarded funding upon the first submission of the grant application, and CIHR had no role in the study design.

Availability of data and materials

The authors of this paper are part of the research team who will have access to this study’s dataset for publications. The primary population health and health economic data are governed by privacy legislation and agreements between the research team and provider agencies and are not part of the dataset available for secondary analyses. All data requests should be directed to the corresponding author and would be vetted by the research team and the Regional Ethics board.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SM is the nominated PI of the study and has been involved in all aspects of the study design and implementation. She is also the clinical supervisor at the CAMH site in Toronto. She contributed to revising this manuscript. JK is the co-PI of the study and has been involved in all aspects of the study design and implementation. She is also a co-clinical supervisor at the CAMH site in Toronto and oversees the use of the DBT fidelity measure. She contributed to revising this manuscript. AC is the co-PI of the study and has been involved in all aspects of the study design and implementation. He is also a co-clinical supervisor for the SFU/DBT Centre of Vancouver site. He contributed to revising this manuscript. TG is a co-investigator of the study and was responsible for substantial contributions to the study design and the analytic approach. He is responsible for overseeing the database development and data collection as well as the health economic analyses. He contributed to reviewing and revising this manuscript. DLS is a co-investigator of the study and was responsible for substantial contributions to the design of the study and development of the data analytic approach. He also contributed to reviewing and revising this manuscript. KDG is a co-investigator and prepared an initial draft of this manuscript. She is responsible for overseeing the training and reliability of study assessors at both sites and has contributed to all aspects of the study design. WI is a co-investigator of the study and made substantial contributions to the design of the health economic aspect of the study. She is responsible for the design, implementation, and analysis of economic data. She contributed to reviewing and revising this manuscript. JSH is a co-investigator of the study and is responsible for the design and planning of the health economic evaluation. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval to conduct this study was approved by the research ethics boards at CAMH on May 15, 2014 (#026/2014) and at Simon Fraser University on August 28, 2015 (#2014 s0263).

Prospective participants completed a brief telephone screen and if it appeared that they fulfilled inclusion criteria, they were invited to attend an in-person screen assessment. At this appointment, trained study assessors provided prospective participants with written and verbal information about the study and included time for individuals to ask questions. Prospective participants were then asked to sign the consent form, which was co-signed by the assessor. Consent forms are signed to acknowledge their understanding and agreement to participant in all aspects of the study and the ability to withdraw their consent at any time.

In September 2015, the Principal Investigators (SM, AC) applied for and received an ethical amendment to the original approved application to recruit participants from the existing study to participate in a 2 year genetics sub-project. A separate consent procedure and consent form was developed for this sub-project.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

McMain, S.F., Chapman, A.L., Kuo, J.R. et al. The effectiveness of 6 versus 12-months of dialectical behaviour therapy for borderline personality disorder: the feasibility of a shorter treatment and evaluating responses (FASTER) trial protocol. BMC Psychiatry 18, 230 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1802-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1802-z