Abstract

Background

Despite the sharp rise in antidepressant use, the underutilization of mental healthcare services for depression remains a concern. We investigated factors associated with the underutilization of mental health services for potential depression symptoms in the Republic of Korea, using a nationally representative sample.

Methods

Data were obtained from the Community Health Survey (2011–2012) conducted in the Republic of Korea. Participants comprised adults who reported potential depression symptoms during the year prior to the study (n = 21,644); information on professional mental healthcare use for their symptoms was obtained. The association of demographic, socioeconomic, and health-related factors with consultation use was analysed via multiple logistic regression. Adjusted odds ratio and 95 % confidence intervals were estimated.

Results

Among those reporting potential depression symptoms, only 17.4 % had consulted a medical/mental health professional. Elderly individuals of both genders had significantly lower consultation rates compared to middle-aged individuals. Unmet healthcare needs and a history of diabetes mellitus were associated with lower consultation rates. After stratification by age, elderly individuals with the lowest education and income level were significantly less likely to seek professional mental health services. Married, separated, or divorced men had lower consultation rates compared to unmarried individuals, whereas married, separated, or divorced women had higher rates.

Conclusions

The results suggest that target strategies for vulnerable groups identified in this study—including elderly individuals—need to be established at the community level, including strengthening social networks and spreading awareness to reduce the social stigma of depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It is estimated that almost 350 million people suffer from depression globally [1]. Unipolar depressive disorder—the third leading cause of disease burden in 2004— is expected to become the leading cause of disease burden worldwide by 2030 [2]. Depression may result in poorer well-being [3], and is a predictor of suicidal behaviours, along with affective temperament and hopelessness [4]. Despite the drastic increase in antidepressant use since the 1990s in Western countries [5, 6], elderly individuals’ underutilization of mental health services for depression remains a concern [7, 8]. In Asian countries, people with depressive symptoms are less likely to visit mental health professionals due to the stigma of mental illness [9–11]. However, few studies have examined mental health service use among Asians. In order to develop prevention strategies for depression and suicide, factors associated with the underutilization of mental health services need to be identified.

Among determinants related to mental health service use, previous studies on determinants of mental health service use have focused on help-seeking attitudes, finding that elderly individuals showed more positive attitudes than younger individuals did [12–14]. A population-based study showed that those with lower education and income had negative help-seeking attitudes for mental illness [13, 15]. However, the age difference in the association between socioeconomic status and help-seeking attitudes or behaviours for mental illness has rarely been evaluated. Older adults—despite their relatively positive help-seeking attitudes—are less likely to have access to resources including mental health professionals [16, 17] and rarely consult mental health professionals, compared to middle-aged individuals [7]. Particularly in the Republic of Korea, there has been growing concern about elderly individuals’ mental health problems because of the steep rise in suicide rates, from 42.0 per 100,000 habitants in 2001 to 81.9 in 2010 [18]. Thus, socioeconomic and health-related factors associated with the underutilization of mental health services need to be explored with a focus on age differences.

In the present study, we focused on depression symptoms, investigating demographic, socioeconomic, and health-related factors associated with the underutilization of professional mental health services based on a representative community sample. Additionally, we conducted identical analyses after stratification by age and gender to assess effect modification of the association between socioeconomic and health-related factors and professional mental health service use.

Methods

Participants

The Community Health Survey (CHS), a nationwide cross-sectional survey, was conducted by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A systematic, stratified, and multi-stage cluster sampling was performed using the National Census Registry data. The weight assigned to each participant was calculated based on geographic and demographic distribution to allow the extrapolation of findings for the entire population of the Republic of Korea. From the total of 458,147 survey participants (see Additional file 1: Table S1), the total number of participants was 423,106 (209,660 in 2011 and 213,446 in 2012) after excluding missing values.

All participants in the CHS were asked, ‘Were you feeling sad or hopeless for two consecutive weeks during the past year, such that you had difficulty performing your usual activities?’ Only those who responded ‘Yes’ were considered to show ‘potential depression symptoms’ (n = 23,625) and were included in the present study. We obtained the permission to use the CHS data from Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the CHS website (https://chs.cdc.go.kr/chs/index.do) [19].

Measurement

For the CHS, participants reporting potential depression symptoms were asked, ‘Have you ever consulted professionals (e.g. medical doctors, professional counsellors) for the depressive symptoms?’ In the present study, professional mental health service use or consultation was determined by their ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response.

Participants were grouped according to age: young adults (19–44 years), middle-aged individuals (45–64 years), and elderly individuals (65 years and older) [20]. Socioeconomic factors included education level (primary or less, middle school, high school, and college or more), marital status (married, separated/divorced, and unmarried), income (quartiles 1–4, determined by household income: monthly individual income divided by the square root of household size) [21], residence (metropolitan, urban, and rural), and employment status (unemployed and employed). Health-behaviour factors included smoking status (current, former, and non-smoker), drinking status (drinker and non-drinker), physical activity (‘yes’ or ‘no’), and sleep (<6, 6–9, and ≥9 h per day) [22]. Health-condition factors included subjective health status (good, moderate, and poor), perceived stress susceptibility (very high, high, low, and very low), unmet healthcare needs (‘yes’ or ‘no’), and a medical history (any previous diagnosis of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia, cardiovascular disease [CVD; including angina, myocardial infarction, and stroke], arthritis, and asthma).

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS institute, Cary, NC). Data with missing values in any question were excluded (n = 1,981). Thus, 21,644 participants were included in the statistical analysis. Weighted frequency was estimated using ‘PROC SURVEYFREQ’ for categorical variables. Chi-squared tests were used to determine the significance of differences between participants who did and did not receive professional mental health consultation for potential depression symptoms. Multiple logistic regression was used to obtain adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) using ‘PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC’. In addition, the identical analysis was conducted after stratification by gender and age. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

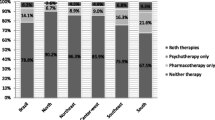

The study population’s general characteristics and utilization of professional mental health services for potential depression symptoms are summarized in Table 1. Among the 21,644 participants who reported potential depression symptoms, 3,762 (17.4 %) had consulted a mental health professional for their symptoms. The proportions of those seeking professional mental healthcare differed significantly for all variables except marital status (p = 0.393) and physical activity (p = 0.348).

Factors associated with utilization of professional mental health services for potential depression symptoms by gender are shown in Table 2. The total ORs by gender indicate that men (OR = 0.73; 95 % CI: 0.63 − 0.85) used mental health services for potential depression symptoms less frequently than did women. Both elderly men (OR = 0.67; 95 % CI: 0.54 − 0.83) and women (OR = 0.69; 95 % CI: 0.58 − 0.83) showed significantly lower rates of professional mental health service use. Regarding socioeconomic factors, women with primary education or lower (OR = 0.80; 95 % CI: 0.64 − 0.99) and both, employed men (OR = 0.55; 95 % CI: 0.45 − 0.67) and women (OR = 0.81; 95 % CI: 0.72 − 0.91) were significantly less likely to seek consultation. In terms of health behaviours, drinkers were less likely to seek consultation. Unmet healthcare needs in both genders and a history of diabetes mellitus in men were negatively associated with professional mental health service use for potential depression symptoms.

Table 3 shows professional mental health consultation rates in men by age. Young adult (OR = 0.39; 95 % CI: 0.18 − 0.84) and elderly men (OR = 0.70; 95 % CI: 0.54 − 0.90) with the lowest education level had significantly lower rates of professional mental health service use than did those with the highest education level. Among elderly men, rates of utilization for those in the lowest (OR = 0.36; 95 % CI: 0.29 − 0.45) and second lowest (OR = 0.43; 95 % CI: 0.34 − 0.54) income quartiles differed significantly from those in the highest quartile. With respect to health-related factors, elderly current smokers vs. non-smokers (OR = 0.54; 95 % CI: 0.41 − 0.70) and drinkers vs. non-drinkers (OR = 0.65; 95 % CI: 0.52 − 0.80) were significantly less likely to seek consultation. Middle-aged individuals with unmet healthcare needs had a significantly lower consultation rate than did those who did not have unmet needs (OR = 0.73; 95 % CI: 0.58 − 0.92). Low perceived stress susceptibility among middle-aged individuals was associated with a lower consultation rate (OR = 0.64; 95 % CI: 0.43 − 0.96), whereas young adults with very high perceived stress susceptibility had higher consultation rates (OR = 5.05; 95 % CI: 3.48 − 7.32). Middle-aged individuals with a history of diabetes mellitus (OR = 0.62; 95 % CI: 0.47 − 0.82) and asthma (OR = 0.65; 95 % CI: 0.47 − 0.91) had lower consultation rates, whereas among elderly individuals, those with asthma had higher consultation rates (OR = 2.94; 95 % CI: 2.46 − 3.53).

Table 4 presents rates of professional mental health consultation for potential depression symptoms in women by age. Only among elderly women were professional mental health consultation rates were significantly lower among those with the lowest education level, compared to those with the highest education level (OR = 0.53; 95 % CI: 0.36 − 0.77). Young adults in the lowest income quartile were significantly more likely to seek consultation (OR = 1.61; 95 % CI: 1.19 − 2.18), whereas elderly individuals in the lowest quartile were significantly less likely to seek consultation (OR = 0.62; 95 % CI: 0.49 − 0.79). With respect to health-related factors, elderly individuals who were former smokers had lower consultation rates (OR = 0.72; 95 % CI: 0.52 − 0.99). Drinkers had significantly lower consultation rates than did non-drinkers among both young adults (OR = 0.57; 95 % CI: 0.45 − 0.72) and middle-aged individuals (OR = 0.79; 95 % CI: 0.67 − 0.92). Low perceived stress susceptibility was associated with lower consultation rates only among elderly individuals (OR = 0.59; 95 % CI: 0.38 − 0.94). Middle-aged (OR = 0.78; 95 % CI: 0.67 − 0.91) and elderly individuals (OR = 0.66; 95 % CI: 0.55 − 0.78) with unmet healthcare needs had significantly lower consultation rates than did those without unmet needs. A history of hypertension (OR = 0.75; 95 % CI: 0.65 − 0.86) and diabetes mellitus (OR = 0.82; 95 % CI: 0.67 − 0.99) were associated with lower rates of consultation, but only among elderly individuals.

Discussion

We investigated demographic, socioeconomic, and health-related, and health-condition factors associated with the underutilization of professional mental health services for potential depression symptoms. Among those who reported depression symptoms during the past year, we observed that 17.4 % had received professional mental health consultation for the depression symptoms. Young adults showed the lowest prevalence of professional mental health service use, but after adjustment of demographic, socioeconomic, and health-related factors, we observed the higher rate of service use, which is inconsistent with a previous study showing more negative attitudes in young and middle-aged adults [7].

A previous study found that elderly individuals with depression were less likely to contact mental health professionals than middle-aged individuals were [7], which is consistent with our findings. Although protective factors—such as high self-reliance—in older adults could be linked to underutilization of mental health services [7, 23], elderly individuals with potential depression symptoms are more likely to have co-existing chronic illnesses, such as cardiovascular disease [24, 25], or functional disability [26]. In addition, prior to committing suicide, elderly individuals tend to contact primary care providers rather than psychiatrists [27]. Collectively, these findings highlight the role of primary care providers in the management of mental health of elderly individuals [28, 29].

The present study showed that men contacted mental health professionals for potential depression symptoms less frequently than women did, which is consistent with previous findings on mental health service use [7, 30]. This may be related to gender differences in help-seeking behaviours [31]. Specifically, men may perceive greater stigma, while women may more easily acknowledge and recognize mental illnesses from nonspecific distressful emotions [32, 33]. Contrastingly, because women tend to internalise their feelings [34], they may have more severe symptoms, which is consistent with the significantly larger proportion of women with high perceived stress in our study.

Although low socioeconomic status may increase the risk for depression and suicidal ideation/behaviours [35–37], the present study showed no significant difference in the rates of seeking formal mental healthcare for potential depression symptoms across income quartiles. This may be attributable to the National Health Insurance system adopted in the Republic of Korea, which may have helped reduce the socioeconomic gap in medical care utilization [38]. However, after stratification by age, young adults with the lowest income level showed higher rates for mental health service use compared to all other income groups, while elderly individuals with the lowest income level had lower consultation rates compared to the highest income level. The effect modification of age may indicate that elderly individuals’ use of mental health services depends more on income than it does for other age groups. In the Republic of Korea, elderly individuals’ suicidal behaviours are most likely motivated by financial problems [39]. Further, the income poverty rates late 2000s for elderly Koreans was 45.6 %, which is four times higher than the average among OECD countries [40]. Although elderly people with financial problems may be exposed to greater psychosocial distress, they were less likely to seek professional help for potential depression symptoms. Further, elderly individuals with a lower income may be socially isolated and may have difficulties engaging in help-seeking behaviours, even though they show positive help-seeking attitudes for mental health problems. Thus, it is imperative that target strategies for elderly individuals’ mental health are established at the community level, such as strengthening social networks.

Although unemployment is associated with suicide [41, 42], the present study suggests that employed individuals were less likely to use professional mental health services than unemployed individuals were. One explanation is the stigma surrounding depressive disorders [43]. In this regard, the Korean government plans to revise the Mental Health Act such that patients with mild symptoms—requiring only outpatient care—will be excluded from the definition of a ‘psychiatric patient’ [44]. However, this change may not address the psychosocial aspects of stigma; interventions that strengthen social supports and discourage discrimination against individuals with mental illnesses need to be enforced. Nonetheless, our findings should be interpreted with caution because we did not consider time-dependent employment status. Those who were unemployed at the time of survey completion may have been previously employed and may have lost their jobs as a result of severe depressive symptoms. In this regard, programs in the workplace for employees’ mental health can help prevent the aggravation of depression symptoms.

Patients with diabetes mellitus were significantly less likely to seek consultation for potential depression symptoms, whereas those with other chronic diseases, such as hypertension, had high consultation rates. Diabetes increases the risk for psychosocial problems, which may have an adverse effect on diabetic patients’ self-care practices [45]. A previous study reported that approximately 10 % of patients with diabetes and psychosocial problems received professional help for their psychosocial problems [45]. One explanation for the discrepancy between diabetes and other chronic diseases is that patients with diabetes and psychosocial problems are less likely to engage in effective diabetes management because of the less noticeable symptoms even with poor management (e.g. pain or dyspnea in patients with mild diabetes). However, we were unable to classify participants according to the severity of diabetes mellitus in the present study. Further investigation of the link between diabetes, psychological problems, and mental health service utilization needs to be conducted.

Strengths and limitations

In this study, we used a large and nationally representative sample to investigate the factors associated with utilization rates of professional mental health consultation for potential depression symptoms. However, several limitations should be considered. Healthy individuals were included among those asked to complete the CHS questionnaires. Thus, the survey did not exclusively focus on those with severe mental problems or suicidal completion. However, given that the present study intended to explore factors associated with underutilization of mental health services, the exclusion of severe cases from this study might not have distorted our results. The participants were selected based on a single self-reported item on depressive symptoms, rather than assessments using psychometric instruments. However, this question is used to determine an essential criterion for major depressive disorder as per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition. Thus, regardless of diagnostic criteria for specific disorders, we were able to identify individuals with depressive symptoms who deserve further evaluation by mental health professionals. Moreover, even though participants who reported having consulted a mental health professional may not have met the criteria for depressive disorders, this does not diminish the present findings since our focus was on patients who required mental health consultation rather than those who met the criteria for depressive disorders. Furthermore, we used a cross-sectional design, which precludes any inferences regarding causation (i.e. the possibility of reverse causality remains). Thus, any interpretation of time-dependent variables (i.e. marital, employment, smoking, and drinking status) should be considered with caution; future studies utilizing a prospective design are needed.

Conclusions

In the present study, among those who reported potential depression symptoms, only 17.4 % had consulted a mental health professional for their symptoms. Elderly individuals were less likely to contact mental health professionals for potential depression symptoms compared to middle-aged individuals. In particular, elderly individuals in the lowest income group were less likely to use mental health services compared to the highest income group. To develop prevention and management strategies for elderly individuals with potential depression symptoms, it is necessary to underscore the role of primary care providers and establish target strategies at the community level, such as strengthening social networks.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. However, no additional permissions were required since public access data were used.

Abbreviations

- CHS:

-

Community Health Survey

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

References

World Health Organization. Depression: A Global Crisis. In: WHO Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, editor. Depression: A Global Public Health Concern. Geneva: WHO Press; 2012.

World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva: WHO; 2008. (Online). http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/2004_report_update/en/.

Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Daniels M, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262(7):914–9.

Pompili M, Rihmer Z, Akiskal H, Amore M, Gonda X, Innamorati M, et al. Temperaments mediate suicide risk and psychopathology among patients with bipolar disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(3):280–5.

Pratt LA, Brody DJ, Gu Q. Antidepressant use in persons aged 12 and over: United States, 2005–2008. In: NCHS data brief. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011.

Spence R, Roberts A, Ariti C, Bardsley M. Focus On: Antidepressant prescribing: Trends in the prescribing of antidepressants in primary care. London: The Health Foundation and the Nuffield Trust; 2014.

Crabb R, Hunsley J. Utilization of mental health care services among older adults with depression. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62(3):299–312.

Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(1):55–61.

Chiu HF, Takahashi Y, Suh GH. Elderly suicide prevention in East Asia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(11):973–6.

Georg Hsu LK, Wan YM, Chang H, Summergrad P, Tsang BY, Chen H. Stigma of depression is more severe in Chinese Americans than Caucasian Americans. Psychiatry. 2008;71(3):210–8.

Karasz A. Cultural differences in conceptual models of depression. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(7):1625–35.

Mackenzie C, Gekoski W, Knox V. Age, gender, and the underutilization of mental health services: the influence of help-seeking attitudes. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10(6):574–82.

Jagdeo A, Cox BJ, Stein MB, Sareen J. Negative attitudes toward help seeking for mental illness in 2 population-based surveys from the United States and Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(11):757–66.

Mackenzie CS, Scott T, Mather A, Sareen J. Older adults’ help-seeking attitudes and treatment beliefs concerning mental health problems. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(12):1010–9.

Chang H-J, Lai Y-L, Chang C-M, Kao C-C, Shyu M-L, Lee M-B. Gender and age differences among youth, in utilization of mental health services in the year preceding suicide in Taiwan. Community Ment Health J. 2012;48(6):771–80.

Palinkas LA, Criado V, Fuentes D, Shepherd S, Milian H, Folsom D, et al. Unmet needs for services for older adults with mental illness: comparison of views of different stakeholder groups. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(6):530–40.

Bartels SJ. Improving system of care for older adults with mental illness in the United States. Findings and recommendations for the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(5):486–97.

Statistics Korea. Annual Report on the Cause of Death Statistics (Online). http://kosis.kr/statisticsList/statisticsList_01List.jsp?vwcd=MT_ZTITLE&parentId=D#SubCont.

Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community Health Survey (Online). https://chs.cdc.go.kr/chs/index.do.

De Waal M, Arnold I, Eekhof J, van Hemert A. Somatoform disorders in general practice: prevalence, functional limitations and comorbidity with anxiety and depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:470–6.

The Orgnization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD Framework for statistics on the Distribution of Household Income, Consumption and Wealth. Framework for integrated analysis. p174 (Online). http://www.oecd.org/statistics/OECD-ICW-Framework-Chapter8.pdf.

The International Classification of Sleep Disorders (Revised) 2nd Edition. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; One Westbrook Corporate Center, Suite 920, Westchester, IL 60154-5767, U.S.A.

Nygren B, Alex L, Jonsen E, Gustafson Y, Norberg A, Lundman B. Resilience, sense of coherence, purpose in life and self-transcendence in relation to perceived physical and mental health among the oldest old. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(4):354–62.

Musselman DL, Evans DL, Nemeroff CB. The relationship of depression to cardiovascular disease: epidemiology, biology, and treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(7):580–92.

Shiotani I, Sato H, Kinjo K, Nakatani D, Mizuno H, Ohnishi Y, et al. Depressive symptoms predict 12-month prognosis in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. European J Cardiovasc Risk. 2002;9(3):153–60.

Beekman AT, Kriegsman DM, Deeg DJ, van Tilburg W. The association of physical health and depressive symptoms in the older population: age and sex differences. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1995;30(1):32–8.

Harwood DMJ, Hawton K, Hope T, Jacoby R. Suicide in older people: mode of death, demographic factors, and medical contact before death. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(8):736–43.

Cattell H. Suicide in the elderly. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2000;6(2):102–8.

Brown GK, Bruce ML, Pearson JL. High-risk management guidelines for elderly suicidal patients in primary care settings. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16(6):593–601.

Klap R, Unroe KT, Unutzer J. Caring for mental illness in the United States: a focus on older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(5):517–24.

Piccinelli M, Wilkinson G. Gender differences in depression. Critical review. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 2000;177:486–92.

Williams JB, Spitzer RL, Linzer M, Kroenke K, Hahn SR, deGruy FV, et al. Gender differences in depression in primary care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173(2):654–9.

Kessler RC, Brown RL, Broman CL. Sex differences in psychiatric help-seeking: evidence from four large-scale surveys. J Health Soc Behav. 1981;22(1):49–64.

Eaton NR, Keyes KM, Krueger RF, Balsis S, Skodol AE, Markon KE, et al. An invariant dimensional liability model of gender differences in mental disorder prevalence: evidence from a national sample. J Abnorm Psychol. 2012;121(1):282–8.

Lee HY, Hahm MI, Park EC. Differential association of socio-economic status with gender- and age-defined suicidal ideation among adult and elderly individuals in South Korea. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(1):323–8.

Everson SA, Maty SC, Lynch JW, Kaplan GA. Epidemiologic evidence for the relation between socioeconomic status and depression, obesity, and diabetes. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(4):891–5.

Qin P, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB. Suicide risk in relation to socioeconomic, demographic, psychiatric, and familial factors: a national register–based study of all suicides in denmark, 1981–1997. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(4):765–72.

Kwon S. Thirty years of national health insurance in South Korea: lessons for achieving universal health care coverage. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24(1):63–71.

Statistics Korea. Reason and impulse for suicide. (Korean version). (Online). http://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1W6C13&vw_cd=MT_ZTITLE&list_id=D2151&seqNo=&lang_mode=ko&language=kor&obj_var_id=&itm_id=&conn_path=E1.

The Orgnization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Pensions at a Glance 2013: Retirement-Income Symtems in OECD and G20 Countries. Country-specific highlights: (other countries to be added). KOREA. p4 (English version) Old-age income poverty rates late 2000s. (Online). http://www.oecd.org/els/OECD-PensionsAtAGlance-2013-Highlights-Korea.pdf.

Lewis G, Sloggett A. Suicide, deprivation, and unemployment: record linkage study. BMJ. 1998;317(7168):1283–6.

Blakely TA, Collings SC, Atkinson J. Unemployment and suicide. Evidence for a causal association? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(8):594–600.

Park JE, Cho S-J, Lee J-Y, Sohn JH, Seong SJ, Suk HW, et al. Impact of stigma on use of mental health services by elderly Koreans. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;1–10.

National Assembly Korea: Reducing the scope of mentaly ill person (Mental Health ACT Revision) (Online). http://pal.assembly.go.kr/law/endMainView.do#a(No. 1909081) Korean version.

Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Lauritzen T, Snoek FJ, Matthews DR, Skovlund SE. Psychosocial problems and barriers to improved diabetes management: results of the Cross-National Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN) Study. Diabet Med. 2005;22(10):1379–85.

Acknowledgements

This work was not financially supported by a grant. The authors thank the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for providing access to data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions

JLK, JC, SP, and ECP designed the study. JLK contributed to data collection, organization, and analyses. JLK and JC contributed to manuscript preparation. ECP had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Jeong Lim Kim and Jaelim Cho contributed equally to this work.

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Total participants in the Community Health Survey (N = 458,147). (DOC 83 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J.L., Cho, J., Park, S. et al. Depression symptom and professional mental health service use. BMC Psychiatry 15, 261 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0646-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0646-z