Abstract

Background

Deficits in mindfulness-related capacities have been described in borderline personality disorder (BPD). However, little research has been conducted to explore which factors could explain these deficits. This study assesses the relationship between temperamental traits and childhood maltreatment with mindfulness in BPD.

Methods

A total of 100 individuals diagnosed with BPD participated in the study. Childhood maltreatment was assessed using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ-SF), temperamental traits were assessed using the Zuckerman-Khulman Personality Questionnaire (ZKPQ), and mindfulness capabilities were evaluated with the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ).

Results

Hierarchical regression analyses were performed including only those CTQ-SF and ZKPQ subscales that showed simultaneous significant correlations with mindfulness facets. Results indicated that neuroticism and sexual abuse were predictors of acting with awareness; and neuroticism, impulsiveness and sexual abuse were significant predictors of non-judging. Temperamental traits did not have a moderator effect on the relationship between childhood sexual abuse and mindfulness facets.

Conclusions

These results provide preliminary evidence for the effects of temperamental traits and childhood trauma on mindfulness capabilities in BPD individuals. Further studies are needed to better clarify the impact of childhood traumatic experiences on mindfulness capabilities and to determine the causal relations between these variables.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a severe psychiatric condition marked by a pervasive pattern of emotional dysregulation, impulsive behaviour, identity disturbances and interpersonal conflicts [1]. Previous publications have established that the transaction between biological temperamental predispositions and environmental factors contribute to the development of the disorder [2–4]. BPD has been described as an extreme and maladaptive variant of normal temperamental dimensions [1, 5, 6] such as neuroticism, impulsiveness and aggression- hostility [1, 7]. In parallel, other studies have revealed that certain contextual factors such as adverse childhood experiences are also related to BPD symptoms and its severity [8, 9]. Retrospective studies have found high rates of early traumatic experiences in BPD, comprising 30 to 90 % of BPD cases and including sexual, physical and emotional abuse [10, 11]. Traumatic experiences and neuroticism are also independent predictors of BPD severity [9]. However, it seems that the interaction between these factors (i.e. neuroticism and adverse childhood experiences) is even more complex, as it contributes not only to the severity [8] but also to the development of the disorder [12].

In recent years, psychological treatments that include mindfulness training have been increasingly used to treat individuals with BPD with and without a history of early trauma [13–15]. Moreover, it has been suggested that improvements in the patient’s mindfulness capacities are a common factor associated with the success of evidence-based therapies for BPD [16]. Mindfulness can be described as a particular way to pay attention to the present moment, in an inquiring and accepting manner, without judging or reacting to the experience [17]. The construct of mindfulness encompasses several facets [18, 19]: (1) the capacity to observe and notice the current experience; (2) the ability to describe the experience (i.e., putting into words or labelling the experience), (3) a non-judgemental and non-evaluative stance (i.e., non-judging), (4) non-reactivity to inner experience (i.e., allowing thoughts and feelings to come without getting caught up in them) and (5) acting with awareness (i.e., focusing on the present activity instead of behaving mechanically). The inclusion of mindfulness practices in BPD treatment is based on the idea that individuals with BPD have a deficit in certain important mindfulness capabilities and that this deficit is associated with symptoms of the disorder [20, 21]. Indeed, subjects with BPD display low levels of mindfulness compared to healthy controls and other clinical populations [22–24]. In addition, studies conducted by Wupperman and colleagues [25, 26] suggest an inverse relation between mindfulness and core characteristics of BPD, including neuroticism.

To date, research on the relationship between personality traits and the facets of mindfulness has mainly been conducted in non-clinical samples. Strong, inverse correlations between neuroticism and mindfulness [26] and between impulsivity and two facets of mindfulness (acting with awareness and non-judging) have been reported [27]. However, the influence of life-events on mindfulness capabilities has not been sufficiently explored. An exception to this is the study carried out by Michal et al. [28], in which a significant and negative correlation was found in a non-clinical population between emotional maltreatment and mindful attention and awareness. The inverse relation between certain mindfulness facets and the severity of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms also suggest an association between traumatic experiences and deficits in mindfulness capabilities [29–31].

Given the context described above, in this study we explore the association between temperamental traits, childhood maltreatment, and deficits in mindfulness capacities in a sample of BPD individuals. Since temperamental traits, especially neuroticism, appear to be moderators of the relationship between childhood maltreatment and psychopathology [12] as well as between childhood maltreatment and BPD severity [8], we also explored the role of temperamental traits as moderators of the association between childhood maltreatment and mindfulness. Based on the literature [27, 28], we hypothesized that some temperamental traits (specifically, neuroticism and impulsiveness) would be negatively associated with mindfulness. We also expected to find neuroticism to have a moderating effect on the association between childhood trauma and mindfulness. Research on the association between mindfulness and diverse childhood maltreatment experiences is scant. Therefore, no a priori hypotheses regarding the possible link between specific facets of mindfulness and different types of traumatic experiences were made.

Method

Participants

A total of 133 participants were recruited from the outpatient BPD unit at the Department of Psychiatry of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona, Spain). Only data from participants meeting the inclusion criteria were analysed, resulting in a final sample of 100 participants. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) diagnosis of BPD according to DSM-IV criteria [32] confirmed by two structured clinical interviews: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) [33] and Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R) [34]; (2) age between 18 and 45 years; (3) no current co-morbidity with major depression, bipolar disorder, psychotic disorders, or substance dependence; (4) no severe physical conditions or intellectual disability; and (5) no previous training in mindfulness.

Instruments

Diagnostic measures

To ensure an accurate BPD diagnosis, the Spanish versions of two semi-structured clinical interviews were used. The SCID-II [33] was used to assess personality disorders according to DSM-IV criteria [32]. The SCID-II has shown adequate psychometric properties, including good reliability between interviewers (kappa: 0.85). The DIB-R [34] is a semi-structured interview to establish BPD diagnosis over the last 2 years. The cut-off point of the Spanish version is six (range: 0 to 10). Psychometric properties are good: internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89), sensitivity (0.81), and specificity (0.94). The convergent validity with the diagnosis of the SCID-II is moderate (kappa: 0.59).

Self-report questionnaires

To assess adverse childhood experiences the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire – Short Form (CTQ-SF) [35] was administered. The CTQ-SF contains 28 items and retrospectively assesses childhood abuse and neglect across five subscales described as follows: (a) sexual abuse: sexual contact or conduct between a child under 18 years of age and an adult or older person, (b) physical abuse: bodily assaults on a child by an adult or older person that entail a risk of, or resulted in, injury, (c) emotional abuse: verbal assaults, humiliating or demeaning behaviour directed toward a child by an adult or older person, (d) physical neglect: the failure of caretakers to provide for a child’s basic physical needs (food, shelter, clothing, safety, and health care), (e) emotional neglect: failure of caretakers to meet children’s basic emotional and psychological needs, including love, belonging, support and nurture. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert Scale from “never true” to “very often true”. For each sub-scale a cut-off point is provided in order to identify moderate – severe cases [36]. Across four diverse samples, all sub-scales have shown a good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha): sexual abuse (0.92 to 0.95), physical abuse (0.81 to 0.86), emotional abuse (0.84 to 0.89), physical neglect (0.61 to 0.78) an emotional neglect (0.85 to 0.91) [35].

Temperamental traits were evaluated with the Zuckerman–Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire (ZKPQ) [37], a self-administered 99 item scale (true/false format) based on the Alternative Five Factor Model. The ZKPQ includes five temperamental traits from a psychobiological perspective: Neuroticism–Anxiety (N-Anx), Impulsive– Sensation Seeking (ImpSS), Aggression–Hostility (Agg-Host), Activity (Act), and Sociability (Sy). Additionally, an infrequency scale is provided to assess inattention to the questionnaire. The Spanish version has shown good psychometric properties, including good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.77 to 0.91), as well as satisfactory convergent, discriminant, and consensual validity [37].

The Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) [38] was used as a mindfulness measure. The FFMQ is a 39-item questionnaire that evaluates mindfulness in five facets: (1) observing (noticing or attending to external and internal experiences -e.g., body sensations, thoughts or emotions-), (2) describing (putting words to, or labelling the internal experience), (3) acting with awareness (i.e., focusing on the present activity instead of behaving mechanically), (4) non-judging the inner experience (i.e., taking a non-evaluative stance towards thoughts or emotions), and (5) non-reactivity to inner experience. Participants are asked to rate the degree of concordance with each statement on a five point-likert scale ranging from one (never or very rarely true) to five (very often or always true). Cronbach’s alpha from the Spanish version ranges from 0.80 to 0.91 [39].

Procedure

Study participants were evaluated at our unit during the years 2013 and 2014. As part of our routine assessment, diagnostic interviews were administered in two different sessions. After BPD diagnosis was confirmed, patients were invited to participate in the study. Prior to inclusion, all subjects signed an informed consent in which the study was explained and after that, completed self-report questionnaires. No remuneration (monetary or otherwise) was given for participation. The study was approved by the Ethical Research Committee at the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. Pearson correlation analyses were carried out between childhood maltreatment (CTQ-SF) and mindfulness facets (FFMQ); and between personality traits (ZKPQ) and mindfulness facets (FFMQ).

Multiple hierarchical regression analyses were used to determine the single and interactive effects of childhood trauma and temperamental variables on mindfulness facets. Associations between demographic variables (age, gender, and education level) and dispositional mindfulness were also studied by means of Pearson correlations and Student’s t-test to identify potential covariates for inclusion in the regression models. To create interaction terms and to account for multicolinearity, variables were mean-centred [39]. FFMQ subscales were entered as the dependent variable; temperamental traits (ZKPQ subscales) were entered in step 1, CTQ-SF subscales were included in step 2, and interaction terms (temperamental trait × type of abuse) in step 3.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample

The majority of participants were women (88 %), with an average age of 30.46 years (SD = 6.84). The mean DIB-R score suggest that the severity of BPD was high (M = 7.74, SD = 1.48). On the CTQ-SF subscales, the frequency of severe forms of childhood maltreatment was as follows: severe emotional abuse (63 %); severe emotional neglect (51 %); severe sexual abuse (45 %); severe physical neglect (35 %); and severe physical abuse (20 %). Additional demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1.

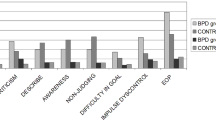

Correlations between childhood trauma and temperamental traits with mindfulness facets

Zero-order associations among childhood trauma (CTQ-SF), temperamental traits (ZKPQ), and mindfulness facets (FFMQ) are shown in Table 2. Negative associations were found between sexual abuse and acting with awareness (r = −.25, p = .03), and non-judging (r = −.27, p = .01). No other significant correlations were found between the other CTQ-SF subscales and mindfulness facets.

N-Anx correlated significantly and inversely with several mindfulness facets: acting with awareness (r = −.49, p = <.001), non-judging (r = −.53, p < .001=), and non-reactivity (r = −.23, p = <.001). In addition, significant but weaker correlations were found between ImpSS and non-judging (r = −.27, p = .01).

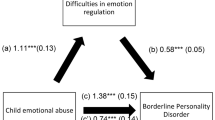

Predictive effect of childhood trauma and temperamental traits on mindfulness facets

Given that no associations were found between demographic variables (age, gender, and education level) and any of the mindfulness facets, these variables were not included in the regression models. Moreover, since our primary interest was to study the effects of both childhood maltreatment and personality variables on mindfulness capacity, regression analyses included only those CTQ-SF and ZKPQ subscales that showed simultaneous significant Pearson correlations (p < .05) with mindfulness. The first model included non-judging as the dependent variable, N-Anx and ImpSS in step 1, sexual abuse in step 2, and interaction terms (N-Anx × sexual abuse and ImpSS × sexual abuse) in step 3. Temperamental traits, N-Anx and ImpSS, were significant predictors of non-judging, explaining 32 % of variance. When sexual abuse was added to the model, this increased the percentage of explained variance to 35 %. Interaction effects did not attain significance in the model. The second model included acting with awareness as the dependent variable, N-Anx in step 1, sexual abuse in step 2, and the interaction term (N-Anx × sexual abuse) in step 3. N-Anx and sexual abuse were significant predictors of acting with awareness, explaining 27 % of the variance. No significant effect of the interaction between N-Anx and sexual abuse was found. Results of the regression analyses are shown in Table 3.

Discussion

The present study sought to investigate the association between temperamental traits, different types of childhood trauma, and various facets of mindfulness in a sample BPD patients. Our results indicate that there is a significant and negative association between N-Anx and several mindfulness facets: acting with awareness, non-judging and non-reactivity and between impulsiveness and non-judging. Additionally, five different types of childhood maltreatment were assessed, but only sexual abuse appears to be related with mindfulness deficits, having a negative impact on acting with awareness and increasing the judgmental stance towards inner and outer experiences. Based on our findings, it appears that temperamental traits might not play a role in moderating the relationship between a history of sexual abuse and mindfulness deficits. Overall, the present study indicates that temperamental traits might have a greater impact on mindfulness capacities than early traumatic experiences in BPD patients.

As suggested by previous work, our results indicate that neuroticism and impulsivity have a significant and negative association with mindfulness facets [20, 27, 28, 40]. However to the best of our knowledge, ours is the first study to test these associations in a BPD sample. N-Anx was a significant predictor of acting with awareness and, together with ImpSS, it was also a significant predictor of non-judging, indicating that higher scores on these traits are related to greater difficulties in being present-oriented and comprise a more judgemental and evaluative stance towards the experiences, consistent with BPD characteristics [21, 41].

In congruence with a previous study [42], it seems that having a history of childhood sexual abuse compromises the ability to act with awareness. Awareness difficulties can be explained by the presence of trauma-related thoughts and memories. In fact, a study involving adult sexual abuse survivors who underwent mindfulness treatment reported a decrease in re-experiencing and avoidance of numbing symptoms and an increase in mindfulness attention and awareness, suggesting a possible relationship between these two aspects [42]. Our results also indicate an association between judgemental information processing and sexual abuse. However, and considering that a history of sexual abuse only increased the explained variance in the regression analyses by a small amount, it seems that –at least in our sample- the impact of temperamental traits on mindfulness capacity is stronger than the influence of sexual abuse. In any case, the association between mindfulness facets and sexual abuse highlights the relevance of addressing mindfulness deficits during the treatment of BPD patients with traumatic histories [13, 14, 43]. Some interventional approaches combine exposure techniques (targeting direct experience processing and fostering awareness of the present experience) with mindfulness practice (to increase acceptance and diminish judgemental stances) [13, 43], and -in light of the present results- this approach would seem to be relevant to the treatment of trauma. Our findings suggest that not all types of childhood maltreatment are related to mindfulness facets in subjects with BPD. Even though sexual abuse may entail more severe and far-reaching consequences for BPD patients than other forms of abuse [11], the lack of a significant association in our study between other types of maltreatment and mindfulness facets was unexpected. Nevertheless, other studies [30, 31, 44] have found negative associations between mindfulness and PTSD symptoms and one study reported an inverse association between emotional maltreatment and awareness [28]. This difference between our study and others may be due to methodological or patient sample differences; however, further research in larger samples will be needed to better assess the relationship between childhood maltreatment and mindfulness facets.

Considering previous research on the moderating role of neuroticism in the psychopathology and BPD severity [8, 12], we hypothesized that temperamental traits would play a role in moderating the relationship between traumatic experiences and mindfulness. Unexpectedly, we did not find any moderating effect of temperamental traits on acting with awareness or non-judging.

The present results should be interpreted in the context of the study limitations. The most important limitation is the cross-sectional design, which prevents us from reaching any conclusion about the direction of the associations. Second, the use of self-report measures to assess the variables (particularly childhood trauma) could have biased the results. Third, a comparison between the BPD group and other clinical populations would have been valuable to determine if the associations found in this study are specific to BPD or not.

Conclusions

Our results provide preliminary evidence demonstrating an association between certain temperamental traits and childhood experiences with mindfulness in a sample of individuals with BPD. It seems that, in individuals with BPD, mindfulness deficits may be more closely associated with high levels of neuroticism and impulsivity rather than early traumatic experiences. Although these findings should be taken with caution, it appears that mindfulness-based interventions could offer a valuable approach to treating emotionally-dysregulated individuals with a history of trauma. This approach might not only increase acceptance, but may also offer a possible pathway to increase awareness while decreasing avoidance symptoms. More research is needed to clarify the relationship between early traumatic experiences and mindfulness, as well as to determine the mechanism underlying the efficacy of mindfulness-based treatments for individuals with a history of traumatic experiences.

Change history

04 September 2018

In the original publication of this article [1] the funding acknowledgement for grant “PI13/00134, ERDF Funds” was missing.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

Beauchaine TP, Klein DN, Crowell SE, Derbidge CM, Gatzke-Kopp L. Multifinality in the development of personality disorders: a biology × sex × environment interaction model of antisocial and borderline traits. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21(3):735–70.

Crowell SE, Beauchaine TP, Linehan MM. A biosocial developmental model of borderline personality: Elaborating and extending Linehan’s theory. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(3):495–510.

Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993.

Samuel D, Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Ball S. Personality disorders as maladaptive, extreme variants of normal personality: borderline personality disorder and neuroticism in a substance using sample. J Personal Disord. 2013;27(5):625–35.

Trull TJ, Widiger TA, Lynam DR, Costa PT. Borderline personality disorder from the perspective of general personality functioning. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112(2):193–202.

Gomà-i-Freixanet M, Soler J, Valero S, Pascual JC, Perez-Sola V. Discriminant validity of the ZKPQ in a sample meeting BPD diagnosis vs. normal-range controls. J Personal Disord. 2008;22(2):178–90.

Martín-Blanco A, Soler J, Villalta L, Feliu-Soler A, Elices M, Pérez V, et al. Exploring the interaction between childhood maltreatment and temperamental traits on the severity of borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(2):311–8.

Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Reich DB, Silk KR. Prediction of the 10-year course of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(5):827–32.

Battle CL, Shea MT, Johnson DM, Yen S, Zlotnick C, Zanarini MC, et al. Childhood maltreatment associated with adult personality disorders: findings from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. J Personal Disord. 2004;18(2):193–211.

Lobbestael J, Arntz A, Bernstein DP. Disentangling the relationship between different types of childhood maltreatment and personality disorders. J Personal Disord. 2010;24(3):285–95.

Laporte L, Paris J, Guttman H, Russell J. Psychopathology, childhood trauma, and personality traits in patients with borderline personality disorder and their sisters. J Personal Disord. 2011;25:448–62.

Bohus M, Dyer A, Priebe K, Krüeger A, Kleindienst N, Schmahl C, et al. Dialectical Behaviour Therapy for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder after Childhood Sexual Abuse in Patients with and without Borderline Personality Disorder: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2013;82:221–33.

Harned MS, Korslund KE, Linehan MM. A pilot randomized controlled trial of Dialectical Behavior Therapy with and without the Dialectical Behavior Therapy Prolonged Exposure protocol for suicidal and self-injuring women with borderline personality disorder and PTSD. Behav Res Ther. 2014;55:7–17.

Stoffers J, Völlm BA, Rücker G, Timmer A, Huband N, Lieb K. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons; 2012.

Bliss S, McCardle M. An Exploration of Common Elements in Dialectical Behavior Therapy, Mentalization Based Treatment and Transference Focused Psychotherapy in the Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. Clin Soc Work J. 2013;42(1):61–9.

Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Delacorte; 1990.

Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13(1):27–45.

Dimidjian S, Linehan MM. Defining an Agenda for Future Research on the Clinical Application of Mindfulness Practice. Am Psychol Assoc. 2003;10:166–71.

Linehan MM. Skills training manual for treating borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press; 1993.

Linehan MM. DBT Skills Training Manual. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2014.

Fossati A, Vigorelli Porro F, Maffei C, Borroni S. Are the DSM-IV personality disorders related to mindfulness? An Italian study on clinical participants. J Clin Psychol. 2012;68(6):672–83.

Soler J, Franquesa A, Feliu-Soler A, Cebolla A, Garcia-Campayo J, Tejedor R, et al. Assesing decentering: Validation, psychometric properities and clinical usefulness of the Experiences Questionnaire in a Spanish sample. Behav Ther. 2014;45(6):863–71.

Wupperman P, Neumann CS, Axelrod SR. Do deficits in mindfulness underlie borderline personality features and core difficulties? J Personal Disord. 2008;22(5):466–82.

Wupperman P, Neumann CS, Whitman JB, Axelrod SR. The role of mindfulness in borderline personality disorder features. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197(10):766–71.

Giluk TL. Mindfulness, Big Five personality, and affect: A meta-analysis. Personal Individ Differ. 2009;47(8):805–11.

Peters JR, Erisman SM, Upton BT, Baer R, Roemer L. A preliminary Investigation of the Relationships Between Dispositional Mindfulness and Impulsivity. Mindfulness. 2011;2(4):228–35.

Michal M, Beutel ME, Jordan J, Zimmermann M, Wolters S, Heidenreich T. Depersonalization, mindfulness, and childhood trauma. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(8):693–6.

Bernstein A, Tanay G, Vujanovic AA. Concurrent Relations Between Mindful Attention and Awareness and Psychopathology Among Trauma-Exposed Adults: Preliminary Evidence of Transdiagnostic Resilience. J Cogn Psychother. 2011;25(2):99–113.

Garland EL, Roberts-Lewis A. Differential roles of thought suppression and dispositional mindfulness in posttraumatic stress symptoms and craving. Addict Behav. 2013;38(2):1555–62.

Vujanovic AA, Youngwirth NE, Johnson KA, Zvolensky MJ. Mindfulness-based acceptance and posttraumatic stress symptoms among trauma-exposed adults without axis I psychopathology. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23(2):297–303.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR). 4th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Gómez-Beneyto M, Villar M, Renovell M, Pérez M, Herández M, Leal C. The diagnosis of personality disorder with a modified version of the SCID-II in a Spanish clinical sample. J Personal Disord. 1994;8:104–10.

Barrachina J, Soler J, Campins MJ, Tejero A, Pascual JC, Alvarez E, et al. Validation of a Spanish version of the Diagnostic Interview for Bordelines-Revised (DIB-R). Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2004;32(5):293–8.

Bernstein DP, Stein J, Newcomb M, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:169–90.

Bernstein DP, Fink. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. A retrospective self-report. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1998.

Gomà-i-Freixanet M, Valero S, Puntí J, Zuckerman M. Psychometric Properties of the Zuckerman-Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire in a Spanish Sample. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2004;20(2):134–46.

Cebolla A, Garcia Palacios A, Soler J, Guillén V, Baños R, Botella C. Psychometric properties of the Spanish validation of the Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ). Eur J Psychiatry. 2012;26(2):118–26.

Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA. Sage; 1991.

Thompson BL, Waltz J. Everyday mindfulness and mindfulness meditation: Overlapping constructs or not? Personal Individ Differ. 2007;43(7):1875–85.

Peters JR, Eisenlohr-moul TA, Upton BT, Baer RA. Nonjudgment as a moderator of the relationship between present-centered awareness and borderline features : Synergistic interactions in mindfulness assessment. Personal Individ Differ. 2013;55(1):24–8.

Kimbrough E, Magyari T, Langenberg P, Chesney M, Berman B. Mindfulness Intervention for Child Abuse Survivors. J Clin Pscych. 2010;66(1):17–33.

Steil R, Dyer A, Priebe K, Kleindienst N, Bohus M. Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Related to Childhood Sexual Abuse : A Pilot Study of an Intensive Residential Treatment Program. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24(1):102–6.

Tyler Boden M, Bernstein A, Walser RD, Bui L, Alvarez J, Bonn-Miller MO. Changes in facets of mindfulness and posttraumatic stress disorder treatment outcome. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2–3):609–13.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM) and by a grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI10/00253 and PI11/00725). The first author (ME) was supported by a grant from Facultad de Psicología (UdelaR). JS was supported by PROMOSAM: Investigación en procesos, mecanismos y tratamientos psicológicos para la promoción de la salud mental, (Red de Excelencia PSI2014-56303-REDT) founded by Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

JS and JCP conceived and planned the study, and provide supervision with the data analysis and interpretation. ME and CC analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. AMB, AFS and ER distributed questionnaires, as well as commented on the last versions of the manuscript together with VP. MGF reviewed the final version of the manuscript and contributed to the interpretation of findings. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Elices, M., Pascual, J.C., Carmona, C. et al. Exploring the relation between childhood trauma, temperamental traits and mindfulness in borderline personality disorder. BMC Psychiatry 15, 180 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0573-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0573-z