Abstract

Background

The study was aimed to describe caries prevalence and severity and health inequalities among Italian preschool children with European and non-European background and to explore the potential presence of a social gradient.

Methods

The ICDAS (International Caries Detection and Assessment System) was recorded at school on 6,825 children (52.8% females). Caries frequency and severity was expressed as a proportion, recording the most severe ICDAS score observed. Socioeconomic status (SES) was estimated by mean a standardized self-submitted questionnaire filled-in by parents. The Slope Index of Inequality (SII) based on regression of the mid-point value of caries experiences score for each SES group was calculated and a social gradient was generated, children were stratified into four social gradient levels based on the number of worst options. Multivariate regression models (Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial logistic and logistic regression) were used to elucidate the associations between all explanatory variables and caries prevalence.

Results

Overall, 54.4% (95%CI 46.7–58.3%) of the children were caries-free; caries prevalence was statistically significant higher in children with non-European background compared to European children (72.6% vs 41.6% p < 0.01) and to the area of living (p = 0.03). A statistically significant trend was observed for ICDAS 5/6 score and the worst social/behavioral level (Z = 5.24, p < 0.01). Children in the highest household income group had lower levels of caries. In multivariate analysis, Immigrant status, the highest parents’ occupational and educational level, only one kid in the family, living in the North-Western Italian area and a high household income, were statistically significant associated (p = 0.01) to caries prevalence. The social gradient was statistically significant associated (p < 0.01) to the different caries levels and experience in children with European background.

Conclusions

Data show how caries in preschool children is an unsolved public health problem especially in those with a non-European background.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The WHO resolution on oral health adopted on 27th May 2021 [1] underlines the need to improve oral health worldwide. In many developed and developing countries oral health care is not covered in primary health care, where high out-of-pocket expenditures for oral health services and care particularly affect disadvantaged populations.

Ending caries and ensuring good oral health is vital for general health at the very early years of children and the quality of life both of children and parents [2]. However, strengthening health-promoting environments in key settings will require multisector action and Health in All Policy approaches [1]. An unequal skewed distribution of caries figures is reported in several countries [3], where differences in disease figure might be explained with the different access to public Oral Health Services combined to different behaviors such as sugar intake, fluoride use and oral hygiene habits.

Children from low-income households have shown a higher caries prevalence than those from high-income households, as well as a greater occurrence of untreated dental caries [4]. Socio-Economic status (SES) is measured by a series of indicators. Considering the socioeconomic status of children, the income of the family, the occupational status and the educational level of parents are among the most important SES indicators.

Measures of socioeconomic inequality in health are a useful tool to assess the scale of inequalities between population groups and within populations [5, 6]. The indices are sensitive to the ordering of social groups and their health gradients, meaning that a negative score indicates an increment of the disease outcome as socioeconomic disadvantage increases [5]. These gradients in health runs from the top to the bottom of the socioeconomic range suggesting the existence of a social gradient [7].

Also, ethnicity and immigrant status, have been found to be significantly related to the presence of caries in the primary dentition [8, 9] without differences among countries from which the parents had immigrated from [10]. Furthermore, children whose families were in the lowest household income quintile, regardless of immigrant group, had the highest caries experience. Parents of children with immigrant background often report low frequency of daily toothbrushing, high consumption of sugar containing foods and infrequent dentist check-ups [11, 12].

Migration is a growing occurrence around the world as well as in Italy. In 2017, the immigration flow amounted to over 343 thousand people with a significative increase over the previous year (+ 14%) [13].

In Italy, the Public Health System has suffered over the last two decades a continuous reduction of the fraction of Gross National Product spent on healthcare; oral healthcare is almost completely provided by private practitioners and mainly financed by patients’ direct payment. In this situation, the spending possibility of the family plays an essential role on the access to dental care.

In 2016, an epidemiological survey called “National pathfinder on children’s oral health in Italy” was promoted by the WHO Collaboration Centre for Epidemiology and Community Dentistry of Milan. It was the second National Survey conducted in Italy on children’s oral health. The project aimed to examine three groups of children at the age of 4, 6 and 12 years old; the examinations started in November 2016 and were completed in June 2017.

The present study is aimed to:

-

i)

describe caries prevalence and severity and socioeconomic inequalities among Italian preschool children with European and non-European background;

-

ii)

compare these inequalities using both absolute and relative measures of socioeconomic inequality in health and.

-

iii)

to explore the potential presence of a social gradient in dental health.

Materials and methods

Study design and study population

The study was designed as a cross sectional survey conform to the STROBE guidelines; data were obtained from the second Italian Pathfinder on oral health, a population-based cross-sectional survey of Italian children aged from 4 to 12 years [4]. The survey protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the University of Sassari (Italy) (AOUNIS: 29/16). In 2017 the Italian population was of 60,589,445 (29,445,741 males and 31,143,704 females); 1.62% were of 3–4 years old.

Sample procedure and data collection were previously described [4].

A multistage cluster sampling was performed as previously reported [14], considering the Italian sections as strata: North-West, North-East, Central, South and Insular Italy. In the second stage the counties of the sections and then the schools (kindergartens) were chosen at cluster level with proportional random selection of participants. A sample size for each stratum was calculated based on an assumed prevalence of dental caries [14] with a standard error of 0.05 and a design effect of 2.5 [15]. The number of 5,100 Italian children aged 4 years was increased by 10%. This strategy provided a sample that was self-weighting. In total, 7,051 children were recruited and 6,825 were examined; 173 children with no parental consent and 53 not present in the classroom at the moment of the examination were excluded. The study sample represented 1.16% of the total Italian population aged 3–4 years attending kindergartens (585,985 children with a frequency of 59.7%.) [13].

Subjects were examined at school by calibrated examiners [16], using a plain mirror (Hahnenkratt, Königsbach, Germany) and the WHO ballpoint probe (Asa-Dental, Milan, Italy) under artificial light. Caries data was recorded using the two-digit codes related to ICDAS for each tooth surface.

Clinical outcomes

Two units of analysis were selected: subject and tooth. The frequency of caries was the outcome variable analyzed by subject, while the most severe ICDAS score observed was the variable used at tooth level. Each tooth was recorded as caries-free (ICDAS 0), enamel lesion (ICDAS 1/2), pre-cavitated lesion (ICDAS 3/4), cavitated lesion (ICDAS 5/6), filled teeth due to caries (Ft) and missing teeth due to caries (Mt). At subject level, the sum of teeth caries affected (ICDAS ≠ 0), filled or extracted due to caries was calculated as Caries Experience (CariesEx).

Socioeconomic status/explanatory variables

European children were defined as children whose both parents were born in one of the European countries, while non-European children were coded as those whose at least one parents born outside Europe. Children were stratified based on their Socioeconomic status and behavioral habits of children/parents/caregivers (prolonged breastfeeding, the use of pacifier at night, brushing frequency, the frequency of a cariogenic diet and smoking habit of the parents) were estimated by mean a standardized self-submitted questionnaire [17, 18] before the clinical assessment.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed separately for European children and those with an immigrant background. Caries experience was first analyzed through cross-tabulations and adjusted for age and sex through regression analysis. Both the questionnaire and oral examination forms were manually checked for the completion of the required information.

An algorithm about the household income was developed derived by the modified Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) equivalence scale (https://www.oecd.org) [19]. The household was assembled via allocating scores to each person in a household and then summing up the equivalence points of all household members [14]. The factor was then categorized in 4 levels, with quartile 1 being the lowest and quartile 4 being the highest. The five Italian areas were ordered following the mean Gross National Product (GNP) per capita starting from the highest (North-West, North-East, Central, South, Islands). As proxy measurements of family’s socio-economic status, the occupational profile and the educational level of both parents and the number of offspring were recorded. The parents’ occupational profile was categorized into 3 levels: un-employment/unskilled jobs as the lowest, skilled jobs/qualified jobs and white-collar jobs as the highest. The educational level was categorized in Low (no education/primary education/lower secondary education), Intermediate (upper secondary) and High (degree, master or doctorate) [20]. Oral health habits (frequency of toothbrushing and fluoride supplements beyond toothpaste), diet (duration of breast-feeding, use of sweetened pacifier at night) and life-style behaviors (parents/guardians smoking habits) were also collected. For each explanatory variable, the group with the most favorable situation was chosen as a reference point from which to measure disparities. The regression between the caries experience (CariesEx) in each household quartile was computed and the Slope Index of Inequality (SII) [21], as of the mid-point value of CariesEx score in each household group, was calculated.

As a proxy for health inequality, a social gradient was generated as the weighted sum of the worst circumstances deriving from social explanatory variables. Children were stratified into four social gradient levels based on their number of worst options: ‘‘best,’’ with up to two; ‘‘good,’’ with three; ‘‘bad,’’ with four; and ‘‘worst,’’ with five or more. Multivariate regression models were used to elucidate the associations between all explanatory variables and health outcome (namely the caries prevalence). Assuming an overdispersion and excess of zero in total sample and in children with European background, the Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial logistic regression was used; while, a logistic regression was used in children with non-European background, assuming a high caries prevalence. Different additional analyses were performed and Mantel Haenszel trends of odds adjusted by immigrant background and area of living were calculated to study the existence, dimensions and direction of the social gradients in oral health.

Stata/SE 16.1 for Mac (Intel 64-bit) and SPPS 27 were used to account for the complex data structure.

Results

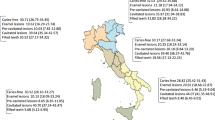

Overall, 6,825 children (52.8% females) were examined, of which 883 (12.9%) were of non-European background. The distribution of caries figures for both European and non-European children across the five different Italian areas (Fig. 1) showed that caries prevalence was statistically significant higher in children with non-European background compared to European children (72.6% vs 41.6% respectively χ2 = 297.29 p < 0.01).

A not equal distribution by sex across both European and non-European groups was recorded; a higher caries prevalence in females in the non-European group (80.8%) was found, while in European background sample a higher prevalence in males (61.1%) was observed (data not in table).

Descriptive and bivariate analysis (by European and non-European background) is displayed in Table 1.

The caries prevalence was statistically associated (Mantel Haenszel trend of odds χ2 = 3.94 p = 0.03) to the area of living ordered by GNP among European children: the caries prevalence increases as the GNP decreases. In children with a non-European background, caries prevalence was not associated with the area of living. The caries prevalence (CariesEx) was statistically significant different across the different household income quartiles, the parents’ occupation both in children with European and non-European background (p < 0.01). Caries figure was also statistically significant associated (p < 0.01) to behavioral factors: Breastfeeding, Pacifier at night, toothbrushing frequency, Cariogenic diet, Smoking habit of parents (see Additional file 1).

The social levels, by equivalized household income, for caries experience and cavitated lesions prevalence for both European and non-European children are clearly demonstrated in Fig. 2: children in the highest household income group had lower levels of caries (either caries experience and cavitated lesions prevalence) than their counterparts in the lowest income group.

The coefficients from the multivariate analysis with negative values indicate that the social disparity in caries favors the more socially advantaged children (Table 2).

In total sample, all the estimated coefficients namely the Immigrant status, the highest occupational and educational level of the parents, only one kid in the family, living in the North-Western Italian area and a high household income, of the Zero-inflated negative binomial logistic model (transformed to incidence rate ratios), were statistically significant associated (p = 0.01 or p < 0.01) to caries prevalence. In European children, the estimated coefficients (Parents’ occupation level, Number of kids in the family, Area of living and Household income) of the Zero-inflated negative binomial logistic model transformed to rate ratios, were statistically significant associated (p < 0.01) to caries prevalence. White-collar parents, family living in North-West and highest household income (4th quartile) played a protective effect on caries prevalence. For the non-European children, all the social background factors were statistically significant associated to caries prevalence (p < 0.01, except for Parents’ educational level, p = 0.04) with an increment of risk in children with white-collar parents and parents with a high education level, while a protective effect was observed for highest quartile of household (3rd quartile) and highest GDP-related area (North-West area). All behavioral and life-style habits considered in the survey were statically significant associated (p < 0.01) to caries prevalence in total sample and in children with European background, while in non-European children the use of pacifier at night was not statistically significant associated to caries prevalence (see Additional file 2).

Overall, the social gradient is clearly able to demonstrate how the worst social factors expose children to a greater risk for each caries level (except cavitated) and the overall caries prevalence (data not in table). The social gradient was statistically significant associated (p < 0.01) to the different caries levels and experience in children with European background (Table 3).

Subjects with the worst gradient had usually the highest Odds-ratios for caries prevalence. As caries experience was so high in children with non-European background, no social gradient was detected.

Discussion

Caries, especially in disadvantaged groups, remains a huge public health problem around the world with an increasing burden of untreated caries [21, 22]. In European Union, an overall increment in caries prevalence was reported in young children with lower socioeconomic status and/or an immigrant background as they are the most vulnerable group within countries [23]. The present survey confirmed it, describing a high caries prevalence in young children living in Italy, especially in those with a non-European background. The association between socioeconomic inequality and caries disease is more pronounced in children with a European background than in children with a non-European background due to the different caries figures in the two groups.

The main finding of this survey suggests that socioeconomic inequality is reflected in a higher caries prevalence and experience. Caries severity fluctuates in a statistically significant way in the different geographical areas. Children with an immigrant background showed a higher prevalence of cavitated lesions, especially in the Insular area of Italy where a low GNP is present.

In this survey, a social gradient in caries distribution was evident among Italian children with a European background, highlighting how income and social status are important determinants in caries figures. The social gradient was less evident in children with a non-European background for different possible reasons. First of all, a not uniform distribution of not European background children in the different social quartiles was noted, since a very poor number of children belonged to families in the Medium–high and non-one in the Highest quartile. This situation is not surprising since contrary to what is observed for Italian natives, immigrants does not contribute to getting access to high-paying occupations [24]. Another reason might be related to the very high caries prevalence in this group which also renders the gradient irrelevant. A high caries prevalence in immigrant population might be due to multiple factors such as sociodemographic, socioeconomic, or cultural factors, probably mediated by specific behaviors such as poor oral hygiene habits and high consumption of foods and drink high in sugars [25]. It is hard to fully explicate health differences because no single factor can generally account for them [26], due to the combined and cumulative effect of risk factors and under different living conditions such as migrant status in this survey. Typically, there is a gradual, if not a linear, trend of declining health status confined to a social group that is at the extreme end of the social scale, while all other groups have relatively good levels of health [1].

In Italy, the fraction of Gross National Product spent on healthcare has been significant reduced during the last two decades as described above, and oral health is lagging behind. Oral care is mainly almost exclusive provided by private practitioners and it is mainly financed by direct payment of the patient or, to a lesser extent, through private insurance schemes. It is consequent that family income is a determining factor in the access of care. Data of the present survey show how caries distribution is associated with mean GNP of the living area of the family.

Among the social variables considered, the highest parents’ educational level plays an ambivalent role: it plays as a protective factor for the total sample, while it increases the caries risk when European background and non-European children are individually analyzed. The increased risk of caries found in non-European children could be related to a higher income that, if not associated to adequate knowledge and behavior, might expose children to a greater risk of disease. However, it is necessary to underline that the number of parents in this group with the highest level of employment was rather small, as proof of what has already been reported above.

Belonging to a family with one play a protective role in children with a European background, while it plays a role in favoring caries in the group of children with a non-European background. Women with a European background in Italy have fewer children (1.19 per capita) than those with a non-European background (1.98 per capita) [27]. In addition, women with a European background have children at a later age, because they are engaged longer in studies and then in looking for a job. This situation leads families with a European background to have fewer children, to have them at an age where there is greater awareness of healthy habits and when there is greater economic well-being. All these factors contribute to reducing the risk of caries. Conversely, women with non-European background have more children at an earlier age than European ones, and these conditions often lead them to a lower educational level and to a lower income or no income at all, conditions favoring a higher risk of caries in offspring [28].

Even if caries is not considered a sex-related disease, many caries risk factors provide a sex bias, placing females at a higher risk, as well as differences in access to dental care justify a higher rate of untreated caries. [29, 30]. In the present survey, this different caries figures between females and males were only found in children with a non-European background.

In the previous pathfinder on pre-school children [14], subjects with a non-European background were not considered since the percentage of immigrants in Italy was low at that time. Despite a different epidemiologic index used (dmfs), a non-homogeneous geographical distribution of caries was already evident, which has not changed to date.

At the best of authors’ knowledge, the present survey is the first National pathfinder carried-out in primary dentition using ICDAS as epidemiological caries index. Another strength of the present survey is the high number of subjects screened, which makes the data representative of the preschool population of each geographic area of the Country. A weakness is the lack of individual income data, since only macroeconomic data of the geographical area of living were available and used for the analyses.

Conclusions

The data derived from the present survey show:

-

In Italy, caries disease in preschool children is an unsolved public health problem, especially in areas where income is low and among the most socially and economically unprivileged groups.

-

The current caries figure requires a political effort and investments in caries promotion and prevention programs in the very early stages of children’s life, especially addressed to family with a non-European background and those living in areas with the lowest economic status.

-

The generated social gradient showed a high association with caries disease in children with a European background, while a less extent of it was noted in children with non-European background.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files [dataraw.xlsx].

References

World Health Organization. Oral resolution EB148.R1. In: WHO Executive Board 148th Resolutions and Annexes. 2021. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB148/B148_R1-en.pdf Accessed on 21 Jun 2021.

Singh N, Dubey N, Rathore M, Pandey P. Impact of early childhood caries on quality of life: Child and parent perspectives. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2020;10(2):83–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobcr.2020.02.006.

Schwendicke F, Dörfer CE, Schlattmann P, Foster Page L, Thomson WM, Paris S. Socioeconomic inequality and caries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent Res. 2015;94(1):10–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034514557546.

Campus G, Cocco F, Strohmenger L, Cagetti MG. Caries severity and socioeconomic inequalities in a nationwide setting: data from the Italian National pathfinder in 12-years children. Scientific Rep. 2020;10(1):15622. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72403-x.

Harper S, Lynch J, Meersman SC, Breen N, Davis WW, Reichman MC. An overview of methods for monitoring social disparities in cancer with an example using trends in lung cancer incidence by area-socioeconomic position and race- ethnicity, 1992-2004. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(8):889–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwn016.

Keppel K, Pamuk E, Lynch J, Carter-Pokras O, Kim I, Mays V, et al. Methodological issues in measuring health disparities. Vital Health Stat 2. 2005;141:1–16.

Arrica M, Carta G, Cocco F, Cagetti MG, Campus G, Ierardo G, et al. Does a social/behavioural gradient in dental health exist among adults? A cross-sectional study. J Int Med Res. 2017;45(2):451–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060516675682.

Stecksén-Blicks C, Hasslöf P, Kieri C, Widman K. Caries and background factors in Swedish 4-year-old children with special reference to immigrant status. Acta Odontol Scand. 2014;72(8):852–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016357.2014.914569.

Arora A, Schwarz E, Blinkhorn AS. Risk factors for early childhood caries in disadvantaged populations. J Investig Clin Dent. 2011;2(4):223–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-1626.2011.00070.x.

Julihn A, Cunha Soares F, Hjern A, Dahllöf G. Development level of the country of parental origin on dental caries in children of immigrant parents in Sweden. Acta Paediatr. 2021;8:2405–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15882.

Vega-López S, Armenta K, Eckert G, Maupomé G. Cross-Sectional Association between Behaviors Related to Sugar-Containing Foods and Dental Outcomes among Hispanic Immigrants. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):5095. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145095.

Salami B, Fernandez-Sanchez H, Fouche C, Evans C, Sibeko L, Tulli M, Bulaong A, Kwankye SO, Ani-Amponsah M, Okeke-Ihejirika P, Gommaa H, Agbemenu K, Ndikom CM, Richter SA. Scoping Review of the Health of African Immigrant and Refugee Children. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7):3514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073514.

Italian National Statistical Institute (ISTAT). 2021. https://www.istat.it/en Accessed 21 Jun 2021.

Campus G, Solinas G, Strohmenger L, Cagetti MG, Senna A, Minelli L, et al. National pathfinder survey on childr’n’s oral health in Italy: pattern and severity of caries disease in 4-year-olds. Caries Res. 2009;43(2):155–62. https://doi.org/10.1159/000211719.

Lwanga SK, Lemeshow S. Sample Size Determi- nation in Health Studies. A Practical Manu- al. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1991.

Campus G, Cocco F, Ottolenghi L, Cagetti MG. Comparison of ICDAS, CAST, Nyvad’s Criteria, and WHO-DMFT for caries detection in a sample of Italian schoolchildren. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;21:4120. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16214120.

Campus G, Cagetti MG, Senna A, Blasi G, Mascolo A, Demarchi P, et al. Does smoking increase risk for caries? a cross-sectional study in an Italian military academy. Caries Res. 2011;45(1):40–6. https://doi.org/10.1159/000322852.

Majorana A, Cagetti MG, Bardellini E, Amadori F, Conti G, Strohmenger L, et al. Feeding and smoking habits as cumulative risk factors for early childhood caries in toddlers, after adjustment for several behavioral determinants: a retrospective study. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-45.

Haag D, Schuch H, Ha D, Do L, Jamieson L. Oral Health Inequalities among Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Children. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2021;6(3):317–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/2380084420939040.

Principi A, Tibaldi M, Quattrociocchi L, Checcucci P. Criteria specific analysis of the Active Ageing Index in Italy. In: Active Ageing Index: Analytical Report. UNECE/European Commission. 2019. https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/pau/age/Active_Ageing_Index/ACTIVE_AGEING_INDEX_TRENDS_2008-2016_web_with_cover.pdf. Accessed 12 Jun 2021.

Blair YI, McMahon AD, Macpherson LMD. Comparison and Relative Utility of Inequality Measurements: As Applied to Scotland’s Child Dental Health. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e58593. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0058593.

Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray CJ, Marcenes W. Global burden of untreated caries: a systematic review and metaregression. J Dent Res. 2015;94(5):650–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034515573272.

Bencze Z, Mahrouseh N, Andrade CAS, Kovács N, Varga O. The Burden of Early Childhood Caries in Children under 5 Years Old in the European Union and Associated Risk Factors: An Ecological Study. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):455. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020455.

Dell’Aringa C, Lucifora C, Pagani L. Earnings differentials between immigrants and natives: the role of occupational attainment. J Migr. 2015;4:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40176-015-0031-1.

Garcia-Pola M, Gonzalez-Diaz A, Garcia-Martin J. Promoting oral health among 6-year old children: The impact of social environment and feeding behavior. Community Dent Health. 2021;38(2):76–82. https://doi.org/10.1922/CDH_00065Garcia-Pola07.

Hämmig Ο, Gutzwiller F, Kawachi I. The contribution of life style and work factors to social inequalities in self-rated health among the employed population in Switzerland. Soc Sci Med. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.041.

Italian Institute of Statistics (ISTAT). Report on natality and fecundity of the resident population in Italy. 2019. https://www.istat.it/it/files/2020/12/REPORT-NATALITA-2019.pdf Accessed on 23 March 2022.

Pabbla A, Duijster D, Grasveld A, Sekundo C, Agyemang C, van der Heijden G. Oral Health Status, Oral Health Behaviours and Oral Health Care Utilisation Among Migrants Residing in Europe: A Systematic Review. J Immigr Minor Health. 2021;23(2):373–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-01056-9.

Martinez-Mier EA, Zandona AF. The impact of gender on caries prevalence and risk assessment. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57(2):301–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2013.01.001.

Cagetti MG, Cocco F, Calzavara E, Augello D, Zangpoo P, Campus G. Life-conditions and anthropometric variables as risk factors for oral health in children in Ladakh, a cross-sectional survey. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21(1):51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-021-01407-4.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the willingness of school authorities and all the participants that provide consent for the participation into the survey. This work was carried out as part of a collaborative study by Italian Study group on Oral Health in children. These are the names of participants: Giuliana Bontà, Maria Grazia Cagetti, Laura Strohmenger (Milano); Stefania Zampogna (Catanzaro); Giuseppe Pizzo, Giovanna Giuliana (Palermo); Livia Ottolenghi, Denise Corridone (Roma), Maria Antonietta Arrica, Guglielmo Campus, Fabio Cocco, Antonella Arghittu, Cynthia Lara-Capi, (Sassari); Roberto Di Lenarda, Milena Cadenaro (Trieste). The study was coordinated by WHO Collaborating Center for Epidemiology and Community Dentistry, University of Milan, Italy. We hereby acknowledge the contributions of the schools involved in the survey.

Funding

The work was supported by the Department of Biomedical, Surgical and Dental Science, University.

of Milan, Italy and by the Department of Surgery, Microsurgery and Medicine Science—School of Dentistry, University of Sassari, Sassari, Italy. The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.C. Contributed to conception, design, formal analysis, methodology, patient qualification for the study, data and statistical analysis, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. F.C. Contributed to conception, review the literature, design, data acquisition, statistical analysis and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript. TGW and AB. Contributed to conception, review the literature drafted and critically revised & editing the manuscript. LS and AA. Contributed to conception, design, drafted and critically revised & editing the manuscript. M.G.C. Contributed to conception, design, drafted and critically revised the manuscript study design, manuscript writing, review final revision of the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

As written in “Material and methods”, the survey protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the University of Sassari (Italy) (AOUNIS: 29/16).

An information leaflet describing the aim of the project was distributed to parents/guardians of the children, requesting their child’s participation in the survey. Informed consent was obtained from all the parents/ guardians of minors/participates Only children with the leaflet signed by parents/guardians were enrolled. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/).

All the authors provided full consent to publish to BMC Pediatrics.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table 1S

. Caries prevalence in children divided by European and Non-European background across Breastfeeding, Pacifier at night, Brushing frequency, Cariogenic diet, Smoking habit.

Additional file 2: Table 2S.

Multivariate regression coefficients of caries prevalence in total sample and children with European and Immigrant background (behavioral habits).

Additional file 3: Supplementary S3.

Row data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Campus, G., Cocco, F., Strohmenger, L. et al. Inequalities in caries among pre-school Italian children with different background. BMC Pediatr 22, 443 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03470-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03470-4