Abstract

Background

The majority of children with COVID-19 have only minor symptoms or none at all. COVID-19, on the other hand, can cause serious illness in some children, necessitating hospitalization, intensive care, and invasive ventilation. Many studies have revealed that SARS-CoV-2 affects not only the respiratory system, but also other vital organs in the body. We report here a child with an atraumatic splenic rupture as the initial and only manifestation of COVID-19.

Case presentation

A 13-year-old boy with clinical signs of acute abdomen, left-sided abdominal pain, and hemodynamic instability was admitted to the PICU in critical condition. His parents denied any trauma had occurred. In addition to imaging tests, a nasopharyngeal swab was taken for COVID-19 testing, which was positive. The thoracic CT scan was normal, whereas the abdominal CT scan revealed hemoperitoneum, splenic rupture, and free fluid in the abdomen.

Conclusions

The spleen is one of the organs targeted by the SARS-CoV-2. Splenic rupture, a potentially fatal and uncommon complication of COVID-19, can be the first and only clinical manifestation of the disease in children. All pediatricians should be aware of the possibility of atraumatic splenic rupture in children with COVID-19.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in children is usually mild. Rarely they can be severely affected with respiratory failure and multisystem involvement [1]. Recent studies have revealed that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) affects not only the respiratory system but also other vital organs in the body [2]. SARS-CoV-2 tropism for the spleen has already been demonstrated in patients infected with the virus. It appears to have a direct effect on the spleen and lymph nodes, resulting in severe tissue damage [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Infections are a significant etiological factor in atraumatic splenic rupture [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Recently, there have been a few reports of atraumatic splenic rupture in adults with COVID-19, implying that SARS-CoV-2, like other infections, could be the cause [7, 8, 20, 21].

We present the first case of atraumatic splenic rupture in a child, most likely caused by COVID-19. The spleen is a highly vascular organ that filters approximately 10–15% of total blood volume per minute and significant blood loss can occur after rupture from either the parenchyma or the splenic vascular supply. The most common cause of splenic rupture is trauma, while atraumatic splenic rupture is uncommon [12]. Clinical signs of early shock appear if intra-abdominal bleeding exceeds 5–10% of blood volume. Splenic rupture is typically characterized by left-sided abdominal pain and hemodynamic instability. In approximately half of the cases, there is left shoulder-tip pain (Kehr’s sign), which is caused by intraperitoneal blood, causing diaphragmatic irritation [11]. Splenic rupture is generally not considered in the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain, in the absence of trauma. A high index of suspicion for atraumatic splenic rupture is important not only because the condition is uncommon, but also because a delayed diagnosis and treatment of splenic rupture can be life-threatening.

Case presentation

A 13-year-old boy was admitted to Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) in a critical situation. After waking up in the morning, he complained of left-sided abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Over the hours, the pain was intermittent and increasing in intensity.

At admission, the patient looked pale, in a forced sitting position. On physical examination, his abdomen was tender in all quadrants with left upper quadrant pain rated as 10 out of 10 in intensity. The pain was described as very strong and increased if he laid down, thus requiring intravenous opioids. Upon examination, heart rate was 92 bpm along with low blood pressure 82/42 mmHg. Diminished breath sounds at the lung bases were noted, most likely due to limited excursions of the chest due to pain. There was no fever (temperature 36.5 C). There was no rash, nor lymphadenopathy. No hematomas or bruises were observed. After intravenous opioids and liquid administration, blood pressure was normalized.

The patient and his father denied any history of trauma. They insisted the child had been totally healthy up until that morning. The child had no family history of coagulopathies, autoimmune diseases, or malignancies. According to his family, there were no bowel abnormalities; use of thrombolytic or anticoagulant drugs.

Several laboratory and imaging examinations were performed immediately. Given the relatively large number of COVID-19 patients during this period, our main differential diagnoses were either a splenic rupture or a splenic artery thrombosis, due to COVID-19. Therefore, a nasopharyngeal swab specimen was collected for COVID-19 testing.

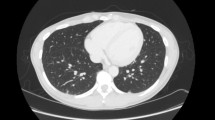

The upright abdominal radiograph showed no abnormalities. Abdominal ultrasound revealed free fluid in the abdomen, but without any clear suspicion, so an emergent Computed tomography (CT) with contrast of the chest and abdomen was carried out. The thoracic CT scan was normal. Abdominal CT (Fig. 1) revealed hemoperitoneum with splenic laceration.

Abdominal CT: There is an intraparenchymal hematoma/laceration measuring > 6 cm which extends to the splenic hilum. (blue solid line) Multiple splenic lacerations were noted inferiorly. No active bleeding on delayed phases. An associated large amount of high density free intraperitoneal fluid/hemoperitoneum around the spleen and liver. (red square dot line) No bone fractures or injuries to other organs

Since the hemoglobin, hematocrit, and patient’s blood pressure were normal, with no active bleeding on CT, the splenic injury was initially managed conservatively. Twelve hours after presentation, a decrease in hemoglobin (Hb = 8.1 g/dL) and hematocrit (HCT = 25.6%) was noted and the patient’s blood pressure started dropping. He received 1 Unit of blood and the decision to proceed to surgery was made. During the operation, it was observed that the patient had plenty of blood in the abdominal cavity. Laceration of the splenic hilum and a large perisplenic hematoma (Fig. 2) was noted and splenectomy was performed. Two additional Units of blood were transfused intraoperatively.

Appearance of the spleen after surgery. In the macroscopic description, the spleen’s measurements were 15 × 9x4 cm (enlarged for his age). Hemorrhagic and necrotic areas of about 8 cm are observed on the hilus. In the microscopic examination, cyclical changes of the type of hemorrhage, necrosis, and vasal congestion were observed

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test, IgM and IgG antibodies for Epstein Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) were negative. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was positive for COVID-19, making us think that the splenic rupture could be a consequence of COVID-19. The child’s clinical condition was stable after surgery. He was discharged, without further problems during the follow-up.

Discussion and conclusions

Splenic rupture is most commonly caused by trauma; however, it can occur without any obvious trauma, which is known as atraumatic or spontaneous splenic rupture, with a reported frequency of less than 1% [22, 23]. Pathologies leading to atraumatic splenic rupture include hematological malignancies, infections, inflammatory diseases and drugs [11, 12, 17]. A literature review by Renzulli et al. showed out that hematological malignancies are the most frequently reported causes of atraumatic splenic rupture with 30% of cases, followed by infections (27%) and inflammatory disease/non-infectious disorders (eg, acute and chronic pancreatitis) with 20% [17]. Atraumatic splenic rupture may occur in a wide age range, from teenagers and young people (particularly from infectious causes) to the elderly and determining the etiology is often challenging. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of atraumatic splenic rupture probably due to COVID-19 in children. There are other cases with atraumatic splenic rupture due to COVID -19, reported in adults [7, 8, 20, 21].

The SARS-CoV-2 virus causes a wide range of disease severity in children [24, 25]. In addition to the respiratory system, it may affect the gastrointestinal tract and other organs [26, 27]. The spleen is one of the organs directly targeted by the virus and according to recent studies, patients with COVID-19 who have left-sided abdominal pain should be evaluated for splenic artery thrombosis and splenic infarction [9, 10, 25, 28, 29]. In their study, Yao Xiaohong et al. suggested that the number of lymphocytes in the spleen was significantly reduced [30]. Hemorrhagic necrosis was present in the spleens of all confirmed SARS studies [26]. Other pathological changes found in our case and reported in all adult cases with atraumatic splenic rupture included thrombosis in a splenic artery as well as rupture and bleeding of a subcapsular hematoma [7, 8, 20, 21].

A spontaneous splenic rupture is a well-known complication of primary EBV infection, but other viruses are also described in literature [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. In a systematic review of 845 patients with an atraumatic splenic rupture, 14.8% were caused by a viral infection, most commonly EBV (74.5% of cases), CMV infection with 9.5% of cases and HIV with 5.8% of cases [17]. The mechanism for the spontaneous hematoma and the splenic rupture is not yet fully clear. Infectious diseases can induce increased intrasplenic tension caused by cellular hyperplasia and vascular occlusion [18]. Similar to these viruses, SARS-CoV-2 could affect the spleen and cause an atraumatic rupture.

Any child with confirmed or suspected COVID-19, in whom abdominal pain develops and extends to the left supraclavicular region (the left shoulder), should be highly suspected of having splenic rupture. Acute abdominal pain can be caused by a wide range of conditions, some of which are life-threatening making the diagnosis challenging. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the diagnostic uncertainty for children with abdominal pain has increased. Gastrointestinal symptoms, which mimic an acute abdomen, can be the primary manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 infection. On the other side, it is well accepted that the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain should include pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome (MIS-C), which manifests as abdominal pain in 50% of affected children. The abdominal pain in MIS-C can be so severe that patients were misdiagnosed with peritonitis or another surgical abdominal condition in many cases reported in the literature [31,32,33]. A thorough history and physical exam can usually narrow the differential diagnosis. The main differential diagnoses in our case were splenic rupture and splenic artery thrombosis. Chest and abdominal CT with contrast along with additional laboratory examinations, helped us exclude other differential diagnosis as pneumonia, pancreatitis, malignancies, etc.

Splenic rupture is characterized by nonspecific abdominal soreness in the left upper quadrant with or without distention, syncope, and a rapid drop in blood pressure, as in our case. It is usually diagnosed later and is a major challenge for radiologists. In cases where the patient is hemodynamically stable and can safely undergo the diagnostic imaging procedure, a CT allows confirmation of the presumptive diagnosis [34, 35]. If the splenic injury is minor, conservative therapy consisting of fluids, with or without blood transfusion(s), and intensive care unit (ICU) admission for close monitoring may be sufficient [34, 35]. When conservative management fails to achieve hemodynamic stabilization, splenectomy may be indicated [34].

Four adult cases of splenic rupture caused by SARS-COV-2 infection are described in the literature. Three of these patients required an emergency splenectomy due to unresponsive hemorrhagic shock, as was the case in our case [9,10,11]. Only one case underwent a splenic artery embolization procedure to stop the hemorrhage [7]. Regardless of etiology, suspicion, and immediate management of atraumatic splenic rupture according to the degree of splenic injury are crucial [36].

In conclusion we believe that the spleen is one of the organs targeted by SARS-CoV-2. Splenic rupture, a life-threatening and uncommon complication of COVID-19, can be the initial and only clinical sign of the disease in children. All pediatricians should be aware of the rare, however possible occurrence of splenic rupture in children with COVID-19. Unlike in adult cases (with respiratory symptoms in addition to the atraumatic splenic rupture), the atraumatic splenic rupture was the first and only manifestation of COVID-19 in our case report [7, 10, 11].

Availability of data and materials

There are no more specific data that could be shared.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- PICU:

-

Pediatric Intensive Care Unit

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- Hb:

-

Hemoglobin

- HCT:

-

Hematocrit

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- EBV:

-

Epstein Barr virus

- CMV:

-

Cytomegalovirus

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- MIS-C:

-

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome children

References

Mary Beth F Son, Kevin Friedman, COVID-19: Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) clinical features, evaluation, and diagnosis. UpToDate. Last updated: Apr 02, 2021.

Zhang Y, Geng X, Tan Y, Li Q, Xu C, Xu J, Hao L, Zeng Z, Luo X, Liu F, Wang H. New understanding of the damage of SARS-CoV-2 infection outside the respiratory system. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;127:110195.

Feng Z, Diao B, Wang R, Wang G, Wang C, Tan Y, Liu L, Wang C, Liu Y, Liu Y, et al. The novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) directly decimates human spleens and lymph nodes. medRxiv. 2020. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.27.20045427v1. Accessed 7 Oct 2021.

Besutti G, Bonacini R, Iotti V, et al. Abdominal visceral infarction in 3 patients with COVID-19. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(8):1926–8.

Pessoa MSL, Lima CFC, Pimentel ACF, Costa Júnior JCG, Holanda JLB. Multisystemic infarctions in COVID-19: focus on the spleen. EJCRIM. 2020;7:001747.

Qasim Agha O, Berryman R. Acute splenic artery thrombosis and infarction associated with COVID-19 disease. Case Rep Crit Care. 2020;2020:4 Article ID 8880143.

Shaukat I, Khan R, Diwakar L, Kemp T, Bodasing N. Atraumatic splenic rupture due to covid-19 infection. Clin Infect Pract. 2021;10:100042.

Mobayen M, Yousefi S, Mousavi M, et al. The presentation of spontaneous splenic rupture in a COVID-19 patient: a case report. BMC Surg. 2020;20:220.

Asgari MM, Begos DG. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis: a review. Yale J Biol Med. 1997;70(2):175–82.

Aldrete JS. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in patients with infectious mononucleosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992;67:910–2.

Looseley A, Hotouras A, Nunes QM, Barlow AP. Atraumatic splenic rupture secondary to infectious mononucleosis: a case report and literature review. Grand Rounds. 2009;9:6–8.

Bjerke HS, Bjerke JS. Splenic rupture. Available at: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/432823-overview#a8 . Last updated: Apr 03, 2017.

Alaoui CR, Rami M, Khatalla K, Elmadi A, Bouabdellah Y. Rupture spontanée de la rate chez un enfant [Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in a child]. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;32:184.

Lee S, Lin AC, Baerg J, Wu E. Spontaneous splenic rupture secondary to epstein-barr virus-induced infectious mononucleosis. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2020;63:101680.

Sergent SR, Johnson SM, Ashurst J, Johnston G. Epstein-Barr virus-associated atraumatic spleen laceration presenting with neck and shoulder pain. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:774.

Stephenson JT, DuBois JJ. Nonoperative management of spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2007;120(2):e432–5.

Renzulli P, Hostettler A, Schoepfer AM, Gloor B, Candinas D. Systematic review of atraumatic splenic rupture. Br J Surg. 2009;96(10):1114–21.

Vidarsdottir H, Bottiger B, Palsson B. Spontaneous splenic rupture and multiple lung embolisms due to cytomegalovirus infection: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;21:13–4.

Vallabhaneni S, Scott H, Carter J, Treseler P, Machtinger EL. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2011;25(8):461-464

Knefati M, Ganim I, Schmidt J, et al. (May 28, 2021) COVID-19 with an initial presentation of intraperitoneal hemorrhage secondary to spontaneous splenic rupture. Cureus. 2021;13(5):e15310.

Agus M, Ferrara ME, Bianco P, Manieli C, Mura P, Sechi R, Runfola M, Polo F, Cillara N. Atraumatic splenic rupture in a SARS-CoV-2 patient: case report and review of literature. Case Rep Surg. 2021;2021:5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5553619 Article ID 5553619.

Munoz Duran AdP, Filomeno DF, Badillo FGL, Gonsalez TMM. Pathological spleen rupture as clinical presentation of diffuse large B –cell Lymphoma: case report. Rev Colomb Radiol. 2017;28(3):4495–8.

Gómez C, Pava R, Salazar A, Sanclemente N. Ruptura esplénica espontánea asociada a linfoma periférico de células T, presentación de un caso y revisión de la literatura. Rev Colomb Cirugía. 2010;25(1):42–7.

Lam GY, Chan AK, Powis JE. Possible infectious causes of spontaneous splenic rupture: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2014;8:396.

WHO-China Joint Mission, Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf.

Zhang QL1, Ding YQ, Hou JL. Detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)- associated coronavirus RNA in autopsy tissues with in situ hybridization. J First Mil Med Univ. 2003;23(11):1125–7.

Ding Y, He L, Zhang Q, Huang Z, Che X, Hou J, et al. Organ distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in SARS patients: implications for pathogenesis and virus transmission pathways. J Pathol. 2004;203(2):622–30.

Xu X, Chang XN, Pan HX, et al. Pathological changes of spleen in ten cases of puncture autopsy with novel coronavirus infection. Chin J Pathol. 2020;49(00):EO14–EO14. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112151-2020041-00278.

Weaver H, Kumar V, Spencer K, Maatouk M, Malik S. Spontaneous splenic rupture: a rare life-threatening condition; diagnosed early and managed successfully. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:13–5.

Xiaohong Y, Tingyuan Li, Zhicheng He, et al. Histological study of three cases of new coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) with multi-site puncture. Chin J Pathol. 2020;49(5):411–7.

Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, Hardwick HE, Pius R, Norman L, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO clinical characterisation protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985.

Whittaker E, Bamford A, Kenny J, Kaforou M, Jones CE, Shah P, et al. Clinical characteristics of 58 children with a pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020;324:259–69.

Harwood R, Partridge R, Minford J, Almond S. Paediatric abdominal pain in the time of COVID-19: a new diagnostic dilemma. J Surg Case Rep. 2020;2020(9):rjaa337.

Hildebrand DR, Ben-Sassi A, Ross NP, Macvicar R, Frizelle FA, Watson AJ. Modern management of splenic trauma. BMJ. 2014;348:g1864. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1864.

Fodor M, Primavesi F, Morell-Hofert D, et al. Non-operative management of blunt hepatic and splenic injuries-practical aspects and value of radiological scoring systems. Eur Surg. 2018;50(6):285–98.

Franklin GA, Casos SR. Current advances in the surgical approach to abdominal trauma. Injury. 2006;37:1143–56.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

The authors are not currently in receipt of any research funding, relating to this research presented in the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IB conceptualized, supervised data collection and drafted the initial manuscript. MB, DC, AD, EC, IG, DS contributed to the acquisition of data. EK revised the manuscript. DK corrected the final English version. All authors have read and approved the manuscript critically.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bakalli, I., Biqiku, M., Cela, D. et al. Atraumatic splenic rupture in a child with COVID 19. BMC Pediatr 22, 300 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03353-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03353-8