Abstract

Background

Abnormal fetal growth is associated with increased cardiovascular risk in adulthood. We investigated the effect of fetal programming on arterial health and morphology during early childhood.

Methods

We examined 90 children (median age 5.81 years, interquartile range: 5.67; 5.95), born small for gestational age with fetal growth restriction, large or appropriate for gestational age (SGA, N = 23, LGA, N = 19, AGA N = 48). We measured body composition, anthropometrics, blood pressure, pulse wave velocity (PWV), lipids, glucose and inflammatory markers, and assessed carotid, brachial, radial and femoral arterial morphology and stiffness using very-high resolution ultrasound (46–71 MHz).

Results

LGA showed increased anthropometry, lean body mass and body mass index. SGA displayed decreased anthropometry and lean body mass. Blood pressure, PWV, carotid artery stiffness and blood work did not differ groupwise. Differences in lumen diameters, intima-media thicknesses (IMT) and adventitia thicknesses disappeared when adjusted for lean body mass and sex. In multiple regression models arterial dimensions were mainly predicted by lean body mass, with birth weight remaining associated only with carotid and brachial lumen dimensions, and not with IMTs. Carotid-femoral PWV was predicted by height and blood pressure only. No independent effect of adiposity was observed.

Conclusions

Arterial dimensions in childhood associate with current anthropometrics, especially lean body mass, and sex, explaining differences in arterial layer thickness. We found no signs of fetal programming of cardiovascular risk or arterial health in early childhood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The gestational milieu, affecting fetal growth and development, has an impact on health in adulthood [1]. Low birth weight or being born small for gestational age (SGA), is associated with an increased cardiovascular risk profile and disease [2, 3], in adulthood. Conversely, the association between high birth weight, or being born large for gestational age (LGA), and cardiovascular risk is not as consistent [2,3,4].

The lifelong development of atherosclerosis begins in childhood and leads to cardiovascular disease, including peripheral artery disease, in adult age [5]. An adverse cardiovascular risk profile and morbidity has been linked to increased common carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) in teenagers and adults, whereas the relationship is not as clear during childhood [6, 7]. Carotid IMT, however, remains a significant source of information on cardiovascular risk when measured in a standardized manner [8], and being born SGA has been determined to be related with increased carotid IMT in early childhood [9].

Carotid IMT and other arterial dimensions have, to our knowledge, so far only been assessed in this setting using conventional ultrasound (< 15 MHz). However, conventional ultrasound has previously been shown to be inadequate for measuring these dimensions in infants and young children and instead very-high resolution ultrasound has been validated (VHRU; peak frequencies 46–71 MHz) as an accurate non-invasive method to assess minute superficial arterial layer thickness in this age group [10, 11]. It is thus still unclear whether the reported increased carotid IMT in children with altered fetal growth reflects an increase in cardiovascular risk profile, due to the use of conventional ultrasound in previous studies. Furthermore, when examined using VHRU the IMT of SGA and LGA infants has been demonstrated to mainly associate with body anthropometrics [12]. Arterial dimensions in early childhood, assessed using VHRU, are related to anthropometrics [13], with lean body mass (LBM) being a significant predictor [14]. We are the first to report on arterial dimensions during early childhood in the setting of abnormal fetal growth using methods validated for this age group.

We aimed to assess the impact of fetal programming, as seen in pre- and postnatal growth, on arterial health and cardiovascular risk during early childhood, by studying arterial structure, stiffness, blood pressure (BP), adiposity, blood glucose, lipids, and inflammatory markers. In addition, we investigated predictors for arterial dimensions and function in this setting. We hypothesized that current body size in general, and LBM in particular, would be the main predictor of arterial dimensions.

Methods

Study design, sample and setting

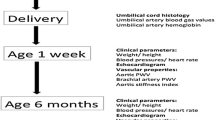

We recruited 174 newborns between November 2011 and January 2014 at the Women’s Hospital, Helsinki Finland to this longitudinal observational cohort study. The newborns, born at weeks 31–42, were recruited into three groups: SGA, LGA or appropriate for gestational age (AGA); defined as weight Z-score <-2 (SGA) and > + 2 (LGA), according to growth charts in use at that time [15]. As the birth weight of the SGA groups was below the 3rd percentile at recruitment, the group corresponded in its entirety to the criteria for fetal growth restriction (FGR), as set by the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology practice guidelines [16]. During the follow-up period new fetal and childhood growth curves were published, and we used these to generate new Z-scores for birth weight and to track growth from primary health care visits [17,18,19]. The new Z-scores corresponded well to the group assignment done at birth, despite minor discrepancies for certain individuals. In order to maintain combability to the neonate stage, no reassignment was done between the groups. Patients with malformations, genetic or chromosomal abnormalities were excluded from the initial recruitment, as reported earlier [12, 20]. In this manuscript we report on the follow-up of 90 preschool children, examined between October 2017 and June 2019, outlined in Fig. 1. During the follow-up period, one child was reported as having been diagnosed with corpus callosum agenesia and one with mild asymmetric cerebral palsy affecting the upper body, both occurring in isolation. As the cardiovascular impact of these findings were minor, none of the subjects who agreed to the follow-up were excluded. Written informed consent was obtained from the children’s guardians. The Helsinki University Hospital Ethics Committee for gynecology and obstetrics, pediatrics and psychiatry approved the research protocol (138/13/03/03/2011 and HUS/2274/2016).

Arterial morphology and stiffness

One skilled investigator obtained VHRU images (peak frequencies 46–71 MHz) using the Vevo MD system, and another blinded investigator analyzed these offline, using the VevoLAB 3.1.1. software (VisualSonics, Toronto, Canada). We examined the common carotid and femoral arteries bilaterally and the right brachial and radial arteries unilaterally. The carotid artery was examined 1 cm proximally of the carotid bulb, the radial artery 1 cm proximally of the palm, the brachial artery 5 cm proximally of the cubital fossa, and the femoral artery 2 cm proximally of the arterial bifurcation at the inguinal fold. We used the highest frequency that reached the far-wall of the artery without compression. Lumen diameter (LD) and IMT were measured in all arteries and intima-media-adventitia thickness (IMAT) was measured in the brachial, radial, and femoral arteries. Adventitia thickness (AT) was calculated as the difference between IMAT and IMT. Measurements were acquired in end-diastole using the leading-edge technique [10]. Each dimension was measured three times using electronic calipers and the mean used in final analyses. We assessed intraobserver and interobserver variability by calculating coefficients of variance (CV) for 10 measurements for each dimension. Intraobserver CV was 0.7–2.5 % for LDs, 4.0–6.0 % for IMTs and 1.0-3.4 % for IMATs. Interobserver CV was 1.6–5.1 % for LDs, 6.0-7.9 % for IMTs and 8.1–15.7 % for IMATs, respectively.

Carotid β-stiffness index (CBSI) [21], carotid distensibility coefficient (CDC) [21], and carotid wall stress (CWS) [22] were calculated using the following formulas:

CCLAS and CCLAD are the carotid artery lumen area in end-systole and end-diastole respectively, CCLDS and CCLDD carotid artery LD in end-systole and end-diastole, respectively and CCIMT the common carotid IMT. SBP and DBP are systolic and diastolic BP and MAP the mean arterial pressure. Carotid-femoral (cfPWV) and carotid-radial pulse-wave velocities (crPWV) were measured at rest in a supine position by a trained technician (Complior Analyse, Alam Medical, Saint-Quentin-Fallavier, France). Mechanosensors were placed at the right carotid, femoral and radial arteries and transit times were recorded twice. Means were used for subsequent calculations. Distances between measurement points were measured using a tape measure to the nearest 0.1 centimeter, and the carotid-femoral distance was multiplied by 0.8. Parallel measurement CVs were 5.7 % for cfPWV and 9.0 % for crPVW. Tolerances for cfPWV and crPWV measurements were 2.0 (IQR: 1.4; 3.3) and 0.4 (IQR: 0.2; 0.6), respectively.

Blood pressure

BP was measured by a trained technician (Carescape v100, GE Healthcare, Chicago, USA), using appropriately sized cuffs from the right arm with the patient sitting upright, following 1-hour rest during imaging [23]. Means of three consecutive measurements were used in analyses. SBP, DBP, heart rate (HT) and MAP (MAP=(2xDBP + SBP)/3) were recorded and BP Z-scores generated for height [23]. Parallel measurement CVs were 4 % for SBP, 4 % for DBP, and 6 % for HR.

Anthropometrics and body composition

We examined head, hip and waist circumferences, arm length, midpoint brachial and antebrachial circumferences, leg length, midpoint thigh and calf circumferences using a tape measure. Limb length was measured to the closest 0.5 centimeters, and waist, hip, and other circumferences to the closest 0.1 centimeter. Height and weight were measured to 0.1 centimeter and 0.1 kg, respectively (Seca285, Seca GmBH & Co. KG, Hamburg, Germany).

We calculated the waist hip ratio, body mass index (BMI) and body surface area (BSA) using the Mosteller formula [24] and generated national Z-scores for height, head circumference and BMI in relation to age, and Z-scores for weight in relation to height [18, 19]. LBM and body fat percentage (BF%) was measured with bioelectrical impedance analysis (InBody 7250, Inbody Bldg., Seoul South Korea).

Lipids, glucose and inflammatory markers

Plasma triglycerides, low- and high-density lipoprotein, total cholesterol and blood glycated hemoglobin were determined from morning venous blood samples following overnight fasting using standard hospital enzymatic assays, fasting plasma glucose using hexokinase assay, serum insulin using immunochemiluminometric assay, and serum high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) using photometric immunochemical assay.

Questionnaires

We recorded information on diabetes, epilepsy, cerebral palsy and slow intellectual development or intellectual disability, along with parental education, household annual income and parental smoking with standard questionnaires and defined parental smoking as either parent currently smoking regularly or sporadically.

Data analysis

We report data as mean (SD), median (Q1; Q3), and N (%) for normally, non-normally distributed and categorical data, respectively. We assessed variable distribution visually and using Shapiro-Wilks test. Far outliers for PWV (median ± 3×IQR) and hs-CRP values outside of laboratory reference values (0.06–3 mg/ml) were excluded.

ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis or Fisher-Freeman-Halton exact tests were applied to compare groups, as appropriate, following post-hoc tests (Dunnet or Games-Howell, Mann-Whitney U or Z-test for proportions) to check difference between SGA, LGA groups and the AGA control group.

Univariate regressions were performed to assess arterial dimension and stiffness predictors (Supplementary Tables 1–3, Additional files 1–3). Predictors are described in tables and presented grouped into domains: (1) size at birth, (2) sex, (3) age, (4) anthropometrics (5) adiposity, (6) BP, (7) blood lipids (8) blood glucose (9) inflammation and (10) parental smoking. Birth weight, anthropometrics and adiposity were considered main predictors, and the other variables examined exploratorily. The association between arterial dimensions and stiffness and anthropometrics were assessed both for local anthropometrics, such as head and limb circumference, and measurements of body size overall, such as LBM and BSA. For arterial wall layers, the unstandardized coefficient was multiplied by 1000, corresponding to layer thickness in micrometers.

We constructed ANCOVA and multiple regression models to assess the association between birth weight, both as a categorial and a continuous variable, and arterial dimensions, local carotid stiffness and PWV, while adjusting for potential confounders. Based on univariate analyses, sex was identified as a potential confounder and body anthropometrics (BSA and LBM), and adiposity (BF% and BMI) as potential mediators for arterial dimensions and local stiffness and were considered for follow-up in the multiple regression models for arterial dimensions and local stiffness. We chose BSA and LBM as anthropometric predictors for the multiple regression models instead of local anthropometric dimensions, as they reflected body size as a whole, were consistently univariately associated with arterial dimension and local stiffness, and performance in univariate analyses were similar.

For PWV, models with height, LBM, BSA, sex, HR and MAP were explored. Height performed better than BSA or LBM in the univariate analyses and was therefore included in the models. HR and MAP are known confounders for PWV [25]. Multiple regression models were examined for multicollinearity, and a VIF cut-off value of 2.5 chosen for the final models. All tests were two-tailed and a p-value < 0.05 deemed significant.

The initial sample size was determined at the neonate stage based on key cardiovascular dimensions and set to detect a clinically relevant difference of 10–20 % in carotid IMT, with a power of 80 % and an α-error of 5 %. The sample size of the follow-up was determined by the number of patients agreeing to the follow-up.

Data was analyzed using SPSS 27 (IBM, New York, New York, USA) and graphs created with GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA).

Results

Background, gestation, and growth

Birth and gestational data reflected inclusion criteria with LGA and SGA showing higher numbers of maternal pre-pregnancy diabetes and preeclampsia, respectively. Longitudinal growth for both SGA and LGA groups showed normalization to the population mean for age during the first 6 to 12 postnatal months (Fig. 2). However, SGA remained slightly smaller at 1 y, as measured by weight Z-score for age (Table 1). When examining follow-up participants and non-participants, we found no differences for group composition, sex, gestational parameters or birth weight, height, or head circumference Z-score. In the LGA group, one child had been diagnosed with epilepsy without the need of regular medication, and one with corpus callosum agenesia, while of the AGA children one had been diagnosed with unspecified motor delay and one with mild asymmetric cerebral palsy. None of the children was reported to have a diabetes.

Growth in Z-scores for age from birth to five years of age (mean and SD). Height (a), weight (b) and head circumference (c) have been collected from primary care growth charts. Chronological age, corrected for prematurity, is displayed on the X-axis. AGA indicates appropriate for gestational age, SGA small for gestational age and LGA large for gestational age

Anthropometrics, unadjusted arterial dimensions, and arterial health

Anthropometrics varied among groups (Table 1). SGA was consistently smaller than AGA, but with no difference in adiposity. LGA height was similar to AGA, but weight, BMI, BSA, and limb circumferences were higher, along with LBM. BF% was, however, not significantly different between LGA and AGA. Carotid, brachial and femoral LD, and brachial IMT were smaller among SGA, but LGA arterial dimensions were no different from AGA (Table 2). No intimal thickening (> 0.06 mm) was found. We found no differences in blood lipids, glucose, hs-CRP, local carotid stiffness, PWVs or BPs.

Predictors of arterial dimensions

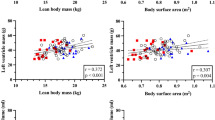

The results of the univariate regressions for arterial dimensions are summarized in Supplementary Tables 1–2, Additional files 1 and 2. Birth weight was significantly associated with all LDs and femoral IMT. Male sex was positively associated with carotid and brachial LD and brachial and radial IMT. For LDs, current body size in general, and especially LBM and distal limb circumferences were significant predictors (Fig. 3). LBM consistently performed slightly better than BSA. Distal limb circumferences showed similar associations to LBM, performing slightly better than BSA for all LDs, and slightly better than LBM for carotid and radial LDs (Supplementary Tables 1, Additional file 1). Adiposity, measured as BMI, was weakly associated with carotid and femoral LD only.

Arterial dimensions plotted against body surface area. Panel (a) shows the common carotid, panel (b) the brachial, panel (c) the radial and panel (d) the femoral artery. AGA indicates appropriate for gestational age, SGA small for gestational age, LGA large for gestational age, LD lumen diameter, IMT intima-media thickness, AT adventitia thickness, and B the unstandardized coefficient

Body size was the strongest predictor of arterial wall layers (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Tables 2, Additional file 2), with no consistent difference between LBM and BSA. Distal limb circumferences performed overall similar to LBM and BSA and were consistently more strongly associated with arterial layers compared with proximal limb circumferences. Adiposity was significantly associated with brachial and femoral IMT and AT only. Total cholesterol associated weakly with carotid and femoral IMT and along with low-density lipoprotein with femoral AT. Both glucose and insulin showed weak positive associations with femoral IMT. No relations between arterial dimensions and BP, hs-CRP, or parental smoking were found.

Predictors of arterial stiffness

Results of univariate analyses for arterial stiffness and function are summarized in Supplementary Tables 3, Additional file 3. cfPWV was associated with body size, most strongly with height. There was a significant association with BF%, but not BMI, as well as SBP, DBP, MAP, hs-CRP and triglycerides. Birth weight, age, male sex or blood glucose did not associate with cfPWV.

No consistent predictors of crPWV, CDC, CBSI or CWS were found.

Birth weight and arterial dimensions and stiffness, adjusted for body size and sex

We found no differences for arterial dimensions or stiffness between the SGA, LGA and AGA groups, when adjusting for sex and LBM or BSA (Supplementary Tables 4, Additional file 4). The linear associations between birth weight and arterial dimensions were explored with multiple regression models, with birth weight Z-score together with sex, current body size (LBM or BSA), and adiposity (BF% or BMI) entered as predictors. Neither BMI nor BF% remained independent predictors once birth weight Z-score, sex and LBM were adjusted for, and as neither improved model fit measured as adjusted R2, they were not included in the final models. Final models for arterial dimensions were created with birth weight, sex and LBM as predictors, as using BSA instead of LBM only improved model fit slightly for two parameters: carotid LD and brachial IMT (adjusted R2 0.287 and 0.233, for both p <0.001). This model was significant for carotid, brachial, radial and femoral LD, brachial IMT and femoral IMT and AT (Table 3). Birth weight remained an independent predictor for carotid and brachial LD, while LBM remained a significant predictor for carotid and femoral LD, and male sex for carotid and brachial LDs. Intima-media thicknesses were independently associated only with LBM. For PWV, birth weight, height, MAP and HR were chosen as predictors for the final model (Table 3), as this model had higher adjusted R2 than models with BSA or LBM. Sex was not included in the final model, as it neither improved model fit nor showed an independent association. cfPWV was independently associated with height and BP, but not with birth weight. The models were not able to predict local carotid function or crPWV.

Discussion

In this study we assessed the impact of abnormal fetal body growth on arterial morphology, stiffness, and arterial health overall during early childhood. We included postnatal body growth, sex, body composition, and comprehensive measures of cardiovascular risk in the analyses. Although significant independent associations between birth weight and arterial LDs were found, we report no independent associations between restricted or excessive fetal growth and arterial layer thickness or stiffness. In addition, we found no consistent associations between abnormal fetal growth and traditional cardiovascular risks including measures of adiposity, BP, blood lipids, glucose or inflammation. Overall, these findings are consistent with the absence of adverse arterial health effects of fetal programming during early childhood related with abnormal fetal growth.

Increased carotid IMT has, in contrast to our findings, been linked with SGA during early childhood [9]. However, studies are inconclusive, as both increased carotid IMT [26,27,28,29] and normal carotid IMT [30], and increased [29] and normal [26] aortic IMT have been reported in SGA children, along with normal carotid IMT in LGA children [31]. We speculate that this could be due to limitations in conventional ultrasound axial resolution applied in earlier studies. The main limiting factor of B-mode ultrasound is axial resolution [32], and conventional ultrasound has been shown to be inadequate for measuring carotid IMT in infants and young children [10, 11]. The arterial wall layer thickness measurement levels reported in study are below the axial resolution of conventional ultrasound for the peripheral arteries and bordering the axial resolution for the carotid artery.

We report no abnormalities in arterial health, including PWV and BP, nor in adiposity, blood glucose or lipids during early childhood following abnormal fetal growth. Increased cfPWV has previously been reported in SGA preschool children [29] and adolescents [33]. Similarly, increased aortic stiffness has been reported in SGA preadolescent [34], but not in young children [27]. Both increased [28] and normal [30] BP have been demonstrated in SGA children. Despite associations between abnormal fetal growth and cardiovascular disease having consistently been reported in adult age, our results suggest that arterial health is unaffected during early childhood or that these changes are so small that they are undetectable even when using improved contemporary very-high resolution methods.

In this study we show that current body size in general, and LBM in particular, is a strong predictor of arterial dimensions in young children, also in the presence of abnormal prenatal growth and postnatal normalization of growth. Our study shows larger arterial dimensions in males compared with females, especially for upper body arterial dimensions. The effect of adiposity on arterial dimensions seems very limited during early childhood, as adding adiposity to the multiple regression analyses did not consistently improve model fit. This is supported by the strong univariate associations with antebrachial, calf and head circumferences, which reflect LBM and are likely less influenced by adiposity during early childhood. This is coherent with our earlier findings in this cohort during the newborn stage [12], as well as in similarly aged children of mothers with obesity and gestational diabetes [14]. However, as there was a significant association between size at birth and carotid and brachial LD in the multiple regression models, this suggest that lumen growth might not follow the overall growth of the body in this setting. Moreover, this disproportion between body and arterial dimensions seemed to be confined to the SGA group as we found no differences between unadjusted LGA and AGA arterial dimensions. However, these results were not observable for arterial wall layer thickness, or radial and femoral artery LD. We realize that the large number of univariate comparisons, combined with a significance level of p < 0.05, raises the risk of type I error, especially for the weaker univariate associations. However, as the association between LBM and arterial dimensions were overall highly significant, and this conclusion was supported by the strong associations with distal limb circumferences, the risk of type I error influencing the conclusion is negligible.

Our study is limited by the relatively small sample size and the lack of differentiation between early- and late-onset FGR, as we did not gather information on the time-of-onset of FGR. However, the SGA group filled the criteria for FGR in its entirety, and the normalization of postnatal SGA and LGA body growth trajectories during the first postnatal 6–12 months is consistent with an aberrant fetal growth prenatally. A possible confounder for growth and cardiovascular risk could be prematurity, as prematurity has been associated with similar cardiovascular risk factors as low birth weight [35]. However, as the difference in gestational age between the groups was non-significant, and all three groups contained both premature and full-term children, the effect of prematurity on our conclusions is likely negligible. Bioimpedance derived LBM during early childhood is known to systematically underestimate fat mass [36], limiting the comparisons of LBM assessed with other methods. We also did not assess aortic IMT, which has recently been proposed as marker of early subclinical atherosclerosis in children [37]. However, assessing carotid IMT has long been the standard and is still considered a valuable marker for cardiovascular risk [6, 8, 38]. The strengths of this study include the use of methodology specifically validated for small children, the well characterized longitudinal cohort sample, and the rigid inclusion criteria for abnormal fetal growth with SGA and LGA groups containing the 2.3 most extreme percentiles only.

Conclusions

Arterial health is not altered during early childhood in the setting of abnormal fetal growth. Arterial dimension growth largely follows postnatal body growth overall and is mainly predicted by current anthropometrics determined by LBM and sex. The present study found no evidence of fetal programming of cardiovascular disease, altered cardiovascular risk or arterial health during early childhood, suggesting that these changes occur later in life.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AGA:

-

appropriate for gestational age

- AT:

-

adventitia thickness

- BF%:

-

body fat percentage

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- BP:

-

blood pressure

- BSA:

-

body surface area

- cfPWV:

-

carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity

- crPWV:

-

carotid-radial pulse-wave velocity

- CBSI:

-

carotid β-stiffness index

- CDC:

-

carotid distensibility coefficient

- CV:

-

coefficient of variation

- CWS:

-

carotid wall stress

- DBP:

-

diastolic blood pressure

- hs-CRP:

-

serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- FGR:

-

fetal growth restriction

- IMT:

-

intima-media thickness

- IMAT:

-

intima-media-adventitia thickness

- LD:

-

lumen diameter

- LBM:

-

lean body mass

- LGA:

-

large for gestational age

- MAP:

-

mean arterial pressure

- PWV:

-

pulse wave velocity

- SBP:

-

systolic blood pressure

- SGA:

-

small for gestational age

- VHRU:

-

very-high resolution ultrasound

References

Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, Thornburg KL. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(1):61–73. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0708473.

Zöller B, Sundquist J, Sundquist K, Crump C. Perinatal risk factors for premature ischaemic heart disease in a Swedish national cohort. BMJ Open. 2015;5(6):e007308-007308. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007308.

Stuart A, Amer-Wåhlin I, Persson J, Källen K. Long-term cardiovascular risk in relation to birth weight and exposure to maternal diabetes mellitus. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(3):2653–2657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.03.032.

Gunnarsdottir I, Birgisdottir BE, Thorsdottir I, Gudnason V, Benediktsson R. Size at birth and coronary artery disease in a population with high birth weight. Am J Clin Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/76.6.1290.

de Ferranti SD, Steinberger J, Ameduri R, Baker A, Gooding H, Kelly AS, et al. Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in High-Risk Pediatric Patients: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(13):e603-e634. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000618.

Urbina EM, Williams RV, Alpert BS, Collins RT, Daniels SR, Hayman L, et al. Noninvasive Assessment of Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Children and Adolescents: Recommendations for Standard Assessment for Clinical Research: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2009;54(5):919–950. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.192639.

Park MH, Skow Á, De Matteis S, Kessel AS, Saxena S, Viner RM, et al. Adiposity and carotid-intima media thickness in children and adolescents: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:161–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-015-0478-5.

Dalla Pozza R, Ehringer-Schetitska D, Fritsch P, Jokinen E, Petropoulos A, Oberhoffer R, et al. Intima media thickness measurement in children: A statement from the Association for European Paediatric Cardiology (AEPC) Working Group on Cardiovascular Prevention endorsed by the Association for European Paediatric Cardiology. Atherosclerosis. 2015;238(2):380–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.12.029.

Epure AM, Rios-Leyvraz M, Anker D, Di Bernardo S, da Costa BR, Chiolero A, et al. Risk factors during first 1,000 days of life for carotid intima-media thickness in infants, children, and adolescents: A systematic review with meta-analyses. PLoS Med. 2020;17(11):e1003414. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003414.

Sarkola T, Redington A, Keeley F, Bradley T, Jaeggi E. Transcutaneous very-high-resolution ultrasound to quantify arterial wall layers of muscular and elastic arteries: validation of a method. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212(2):516–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.06.043.

Sundholm JKM, Olander RFW, Ojala TH, Andersson S, Sarkola T. Feasibility and precision of transcutaneous very-high resolution ultrasound for quantification of arterial structures in human neonates – Comparison with conventional high resolution vascular ultrasound imaging. Atherosclerosis. 2015;239(2):523–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.02.016.

Olander RF, Sundholm JK, Ojala TH, Andersson S, Sarkola T. Neonatal Arterial Morphology Is Related to Body Size in Abnormal Human Fetal Growth. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9(9):e004657. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.004657.

Sarkola T, Manlhiot C, Slorach C, Bradley TJ, Hui W, Mertens L, et al. Evolution of the arterial structure and function from infancy to adolescence is related to anthropometric and blood pressure changes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(10):2516–2524. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.252114.

Sundholm JKM, Litwin L, Rönö K, Koivusalo SB, Eriksson JG, Sarkola T. Maternal obesity and gestational diabetes: Impact on arterial wall layer thickness and stiffness in early childhood - RADIEL study six-year follow-up. Atherosclerosis. 2019;284:237–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.01.037.

Pihkala J, Hakala T, Voutilainen P, Raivio K. Characteristic of recent fetal growth curves in Finland. Duodecim. 1989;105(18):1540–1546.

Salomon LJ, Alfirevic Z, Da Silva Costa F, Deter RL, Figueras F, Ghi T, et al. ISUOG Practice Guidelines: ultrasound assessment of fetal biometry and growth. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019;53(6):715–723. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.20272.

Sankilampi U, Hannila M, Saari A, Gissler M, Dunkel L. New population-based references for birth weight, length, and head circumference in singletons and twins from 23 to 43 gestation weeks. Ann Med. 2013;45(5–6):446–454. https://doi.org/10.3109/07853890.2013.803739.

Saari A, Sankilampi U, Hannila ML, Kiviniemi V, Kesseli K, Dunkel L. New Finnish growth references for children and adolescents aged 0 to 20 years: Length/height-for-age, weight-for-length/height, and body mass index-for-age. Ann Med. 2011;43(3):235–248. https://doi.org/10.3109/07853890.2010.515603.

Karvonen M, Hannila ML, Saari A, Dunkel L. New Finnish reference for head circumference from birth to 7 years. Ann Med. 2012;44(4):369–374. https://doi.org/10.3109/07853890.2011.558519.

Olander RFW, Sundholm JKM, Ojala TH, Andersson S, Sarkola T. Differences in cardiac geometry in relation to body size among neonates with abnormal prenatal growth and body size at birth. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;56(6):864–871. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.21972.

Chirinos JA: Arterial stiffness: basic concepts and measurement techniques. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2012;5(3):243–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12265-012-9359-6.

Boutouyrie P, Germain DP, Fiessinger JN, Laloux B, Perdu J, Laurent S. Increased carotid wall stress in vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Circulation. 2004;109(12):1530–1535. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000121741.50315.C2.

Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, Blowey D, Carroll AE, Daniels SR, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for Screening and Management of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20171904. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-1904.

Mosteller RD: Simplified calculation of body-surface area. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(17):1098. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198710223171717.

Townsend RR, Wilkinson IB, Schiffrin EL, Avolio AP, Chirinos JA, Cockcroft JR, et al. Recommendations for Improving and Standardizing Vascular Research on Arterial Stiffness: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2015;66(3):698–722. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYP.0000000000000033

Sebastiani G, García-Beltran C, Pie S, Guerra A, López-Bermejo A, de Toledo JS, et al. The sequence of prenatal growth restraint and postnatal catch-up growth: normal heart but thicker intima-media and more pre-peritoneal fat in late infancy. Pediatr Obes. 2019;14(3):e12476. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12476.

Castagno M, Menegon V, Monzani A, Zanetta S, Secco GG, Rosso R, et al. Small-for-gestational-age birth is linked to cardiovascular dysfunction in early childhood. Am Heart J. 2019;217:84–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2019.08.004.

Crispi F, Figueras F, Cruz-Lemini M, Bartrons J, Bijnens B, Gratacos E. Cardiovascular programming in children born small for gestational age and relationship with prenatal signs of severity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(2):121.e1-121.e9.

Muñiz Fontán M, Oulego Erroz I, Revilla Orias D, Muñoz Lozón A, Rodriguez Núñez A, Lurbe I. Ferrer E. Thoracic Aortic Intima-Media Thickness in Preschool Children Born Small for Gestational Age. J Pediatr. 2019;208:81–88.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.12.037.

Trevisanuto D, Avezzù F, Cavallin F, Doglioni N, Marzolo M, Verlato F, et al. Arterial wall thickness and blood pressure in children who were born small for gestational age: correlation with umbilical cord high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(1):31–34. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2008.150326.

Atabek ME, Çağan HH, Selver Eklioğlu B, Oran B. Absence of Increase in Carotid Artery Intima-Media Thickness in Infants of Diabetic Mothers. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2011;3(3):144–148. https://doi.org/10.4274/jcrpe.v3i3.28.

Wong M, Edelstein J, Wollman J, Bond MG. Ultrasonic-pathological comparison of the human arterial wall. Verification of intima-media thickness. Arterioscler Thromb. 1993;13(4):482–486. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.ATV.13.4.482.

Stock K, Schmid A, Griesmaier E, Gande N, Hochmayr C, Knoflach M, et al. The Impact of Being Born Preterm or Small for Gestational Age on Early Vascular Aging in Adolescents. J Pediatr. 2018;201:49–54.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.05.056.

Bradley TJ, Potts JE, Lee SK, Potts MT, De Souza AM, Sandor GGS. Early Changes in the Biophysical Properties of the Aorta in Pre-Adolescent Children Born Small for Gestational Age. J Pediatr. 2010;156(3):388–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.10.002.

Morsing E, Liuba P, Fellman V, Maršál K, Brodszki J. Cardiovascular function in children born very preterm after intrauterine growth restriction with severely abnormal umbilical artery blood flow. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21(10):1257–1266. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487313486044.

Lee LW, Liao YS, Lu HK, Hsiao PL, Chen YY, Chi CC, et al. Validation of two portable bioelectrical impedance analyses for the assessment of body composition in school age children. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0171568. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171568.

Skilton MR, Celermajer DS, Cosmi E, Crispi F, Gidding SS, Raitakari OT, et al. Natural History of Atherosclerosis and Abdominal Aortic Intima-Media Thickness: Rationale, Evidence, and Best Practice for Detection of Atherosclerosis in the Young. J Clin Med. 2019;8(8):1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8081201.

Lorenz MW, Gao L, Ziegelbauer K, Norata GD, Empana JP, Schmidtmann I, et al. Predictive value for cardiovascular events of common carotid intima media thickness and its rate of change in individuals at high cardiovascular risk – Results from the PROG-IMT collaboration. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0191172. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191172.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge research coordinators Maria Finne, Hanna Oksa and Terttu Nopanen, for organizing the follow-up visits.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from Sigrid Jusélius Foundation, Medical Society of Finland, Medicinska Understödsföreningen Liv och Hälsa rf, Foundation for Pediatric Research, Stockmann Foundation, and the Dorothea Olivia, Karl Walter and Jarl Walter Perklén Foundation. Open access funded by Helsinki University Library.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.O. analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted and wrote the manuscript text, and prepared the figures. J.S. and S.S. made substantial contributions to acquisition of data, and J.S. further contributed to data analysis and interpretation. T.S. supervised the data analysis, made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of data. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved of the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. We obtained written informed consent from the children’s guardians. The research protocol was approved by the Helsinki University Hospital Ethics Committee for gynecology and obstetrics, pediatrics, and psychiatry (138/13/03/03/2011 and HUS/2274/2016).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary table 1.

Showing the results of univariate regressions for arterial lumen diameters.

Additional file 2: Supplementary table 2.

Showing the results of univariate linear regression results for intima-media thickness and adventitia thickness.

Additional file 3: Supplementary table 3

The results of univariate linear regression results for arterial stiffness and wall stress.

Additional file 4: Supplementary table 4.

ANCOVA models comparing study groups adjusting for confounders.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Olander, R.F., Sundholm, J.K., Suonsyrjä, S. et al. Arterial health during early childhood following abnormal fetal growth. BMC Pediatr 22, 40 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02951-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02951-2