Abstract

Background

Exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months and breastfeeding with complementary feeds until 12 months for HIV exposed and uninfected (HEU) infants or 24 months for HIV unexposed (HU) infants is the current World Health Organisation (WHO) recommendation for low and middle income countries (LMICs) to improve clinical outcomes and growth trajectories in infants. In a post-hoc evaluation of HEU and HU cohorts, we examine growth patterns and clinical outcomes in the first 9 months of infancy in association with breastfeeding duration.

Methods

Two cohorts of infants, HEU and HU from a low-socioeconomic township in South Africa, were evaluated from birth until 9 months of age. Clinical, anthropometric and infant feeding data were analysed. Standard descriptive statistics and regression analysis were performed to determine the effect of HIV exposure and breastfeeding duration on growth and clinical outcomes.

Results

Included in this secondary analysis were 123 HEU and 157 HU infants breastfed for a median of 26 and 14 weeks respectively. Median WLZ score was significantly (p < 0.001) lower in HEU than HU infants at 3, 6 and 9 months (− 0.19 vs 2.09; − 0.81 vs 0.28; 0.05 vs 0.97 respectively). The median LAZ score was significantly lower among HU infants at 3 and 6 months (− 1.63 vs 0.91, p < 0.001; − 0.37 vs 0.51, p < 0.01) and a significantly higher proportion of HU was classified as stunted (LAZ < -2SD) at 3 and 6 months (3.9% vs 44.9%, p < 0.001; 4.8% vs 20.9%, p < 0.001 respectively) independent of breastfeeding duration. A higher proportion of HEU infants experienced one or more episodes of skin rash (44.5% vs 12.8%) and upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) (30.1% vs 10.9%) (p < 0.0001). In a multivariable analysis, the odds of occurrence of wasting, skin rash, URTI or any clinical adverse event in HEU infants were 2.86, 7.06, 3.01 and 8.89 times higher than HU infants after adjusting for breastfeeding duration.

Conclusion

Our study has generated additional evidence that HEU infants are at substantial risk of infectious morbidity and decreased growth trajectories however we have further demonstrated that these adverse outcomes were independent of breastfeeding duration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

UNAIDS reports more than 60% decline in new perinatal HIV infections in 2018 associated with the universal coverage of antiretroviral treatment in antenatal clinics worldwide [1]. South Africa (SA) has an estimated 3.5 million HIV exposed uninfected (HEU) children, the highest recorded in the world [2]. This is attributed to one of the most successful Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT) programmes in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) with universal combination antiretroviral treatment (cART) for all pregnant and breastfeeding women living with HIV, safe breastfeeding guidance for 12 months and repeat HIV testing during pregnancy and breastfeeding to identify new HIV infections and to allow for early commencement of cART [3, 4].

Despite the reduction in perinatal HIV infections and HIV-associated morbidity and mortality in the current ART era, the persistently high rate of gastroenteritis, acute respiratory infections and malnutrition in children in general in SSA is of increasing concern [5,6,7]. The rates of stunting, severe acute malnutrition and moderate acute malnutrition remain high in hospital admissions of HIV infected and HIV unexposed children [8].

Breastfeeding has long been established as the best form of adequate nutrition in infants to reduce the risk of childhood morbidity and mortality [9, 10]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has made substantial investments towards promoting exclusive breastfeeding for six months and continued breastfeeding for up to two years [11]. Much attention, however, has been given to promoting and monitoring breastfeeding among WLHIV. There is limited evidence of feeding practices and infant wellbeing among WNLHIV. In a pooled analysis of 21 clinical trials involving over 19,000 HEU infants in SSA and Asia, half of the infant deaths occurred before three months of age [12]. While mothers not receiving cART for life contributed to almost 50% of infant deaths, never breastfeeding contributed to 10.8% of infant deaths. Current WHO infant feeding recommendations for HIV exposed infants in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are exclusive breastfeeding for six months and continued breastfeeding with complementary feeds until 12 months while mothers are virally suppressed on cART. For WNLHIV, it was recommended that infants be exclusively breastfed for six months but a longer duration of breastfeeding with complementary feeds thereafter until 24 months [11]. Two recent studies in SA reported short breastfeeding duration among women in general regardless of their HIV status [13, 14].

With the high rates of HIV infection in childbearing women in SSA and SA, in particular, there has been widespread use of antiretrovirals for treatment, prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) and infant prophylaxis. The opportunity to assess the growth of infants and rates of malnutrition and childhood infections in infants born to mothers not exposed to antiretroviral drugs is becoming rare [15, 16].

Our study aimed at describing the growth patterns and clinical outcomes in two cohorts of infants born to WLHIV and WNLHIV and living in the same geographical and socioeconomic context. In a secondary analysis of data, we report the incidence of respiratory infections, rash or skin infections, diarrhoea, malnutrition and growth faltering in the first six to nine months of infancy in association with breastfeeding duration.

Methods

This is a secondary analysis of two cohorts of infants born to WLHIV and WNLHIV residing in Umlazi, a peri-urban low-socioeconomic township in South Africa. Between 2007 and 2009, HIV exposed and uninfected (HEU) infants were enrolled in a multi-centred randomised placebo-controlled trial (HPTN046) designed to investigate the efficacy of extended Nevirapine prophylaxis in preventing breastfeeding transmission of HIV-1 [17]. For the secondary analysis, we selected infants who were enrolled in Umlazi and who did not receive NVP prophylaxis, nor did their mothers receive cART during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Between 2017 and 2018, pregnant women without HIV were enrolled in an observational cohort study (CAP088) designed to determine the incidence of HIV during pregnancy and breastfeeding [18].

Infants in the HPTN046 study were enrolled within seven days of birth if they tested negative with HIV DNA PCR, have a birthweight at least 2000 g and be able to breastfeed. Gestational age was not determined. Clinical, anthropometric and infant feeding assessments were conducted by research nurses and clinicians at two, five, six and eight weeks and three, four, five, six, nine, 12 and 18 months. In the CAP088 study, clinical, anthropometric and infant feeding assessments were conducted and documented in the Road-to-Health Card by primary health care nurses as per the IMCI guidelines at three, six and nine months of age. A copy of the completed Road-to-Health Card was filed in the maternal folder.

For this study, the growth outcomes, length and weight measurements at birth, three, six and nine months were used to estimate the weight-for-age (WAZ), length-for-age (LAZ) and weight-for-length (WLZ) z-scores using the WHO growth standards [19]. Infants were classified as being underweight, having stunting or wasting based on WAZ, LAZ and WLZ < -2 respectively [20]. Clinical outcomes included having a minimum of one episode of rash or skin infection, fever, upper respiratory tract infection (URTI), acute gastroenteritis (AGE) and lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) between birth and nine months. Hospitalisation during the first nine months of infancy was also included as a clinical outcome.

Breastfeeding practice was ascertained by a questionnaire and documented as a “Yes” or “No” at three, six and nine months and duration of breastfeeding was determined at nine months or at the last clinic visit if infants were not seen at nine months. Infants in the HPTN046 study were tested for HIV at three, six and nine months using HIV DNA PCR assay. Mothers in the HPTN046 study had a CD4 count done at the time of infant enrolment.

Select data were extracted from the HPTN046 database and transferred to an excel spreadsheet. The substudy Investigator reviewed infant source documents from the CAP088 study and populated the excel spreadsheet with relevant data. The excel database was analysed using the SPSS version 24 statistical package. Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies and percentages, were used to summarise categorical data. We tested for normal data distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. With continuous variables that were not normally distributed, we report the median and IQR. Measures of central tendency mean and median and measures of dispersion such as standard deviation and interquartile range were calculated for numerical variables. Pearson chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to test if there is an association between clinical and growth outcomes and breastfeeding duration in the two cohorts. An alpha value of 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Included in this secondary analysis were 123 HEU infants and 157 HU infants enrolled at birth. WLHIV and WNLHIV were similar in age, with a median age of 25 vs 23 years, respectively (Table 1). Majority of the women living with HIV or without HIV were not married and not living with their partner (91.8% vs 84.7%). A significantly higher proportion of women without HIV were employed (23.6% vs 4.9%) when compared to women living with HIV (p < 0.0001). WLHIV were generally healthy with a median CD4 count of 529 (IQR 457; 612) cells/ml and HEU and HU infants were of similar birth weight (3200 g) (p = 0.878). The two groups of infants (HEU and HU) differed significantly in the duration of breastfeeding, with a larger proportion of HU infants at a primary health care clinic breastfed for less than six months (52.9%) when compared to HEU infants in a breastfeeding study (38.2%) (p < 0.05) (Table 1). Overall, 70% of women who were employed versus 42% of unemployed breastfed for less than six months (p = 0.001).

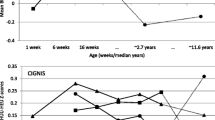

Overall median WLZ scores were consistently and significantly lower in HEU than HU infants at three, six and nine months (Table 2) (− 0.19 vs 2.09; − 0.81 vs 0.28; 0.05 vs 0.97 respectively) (p < 0.001). The median WAZ score was significantly lower in HEU than HU infants at nine months only (0.41 vs 0.85; p < 0.05). In contrast, the median LAZ score was lower among HU infants at three, six and nine months (− 1.63 vs 0.91; − 0.37 vs 0.51; 0.13 vs 0.77) reaching statistical significance at three (p < 0.001) and six months (p < 0.05) only. When compared to HEU infants, a significantly larger proportion of HU infants were classified as underweight (WAZ < -2SD) at three months (1.6% vs 8.18%, p = 0.026) and stunted (LAZ < -2SD) at three and six months (3.9% vs 44.9, 4.8% vs 20.9% respectively) (p < 0.001).

When compared to HU infants a markedly higher proportion of HEU infants experienced one or more episodes of skin rash (12.8% vs 44.5%) and upper respiratory tract infection (10.9% vs 30.1%) (p < 0.0001) (Table 2).

When stratified by breastfeeding duration, the growth and clinical outcomes among HU infants were not significantly different between infants breastfed for less than six months or six months or more (Table 3). In addition, the median LAZ score and the prevalence of stunting did not differ by breastfeeding duration among the HU infants (Table 4).

In a multivariable analysis, the odds of occurrence of wasting, skin rash, URTI or any clinical adverse event in HEU infants were 2.86, 7.06, 3.01 and 8.89 times higher than HU after adjusting for breastfeeding duration (Table 5).

Discussion

In this secondary analysis of growth, clinical and breastfeeding data collected for HEU and HU infants, we report a significantly shorter breastfeeding duration (median 14 weeks) and a higher occurrence of stunting (45% at 3 months and 21% at 6 months) among HU infants in the first six months of life. The shorter duration of breastfeeding was not associated with stunting. We also report lower WLZ scores and higher frequency of rash/skin disease and URTI among the HEU infants independent of breastfeeding duration.

Breastfeeding has long been established as the best form of adequate nutrition in infants to reduce the risk of childhood morbidity and mortality [9, 10]. The WHO has made large investments towards promoting exclusive breastfeeding for six months and continued breastfeeding up to two years [11]. In our study, the median duration of breastfeeding was 20 weeks among HU infants and 26 weeks among HEU infants. Only 46% of HU and 61% of HEU infants were breastfed for six months or more. Early cessation of breastfeeding in the South African population has also been reported in other studies independent of HIV exposure [13, 14]. In Horwood’s study, mothers who were returning to work or school were less likely to breastfeed (AOR 3.76) [14]. This is consistent with our findings: 70% of women who were employed breastfed for < 6 months versus 42% of unemployed breastfed < 6 months.

In our study, a significantly higher proportion of HU infants was underweight at three months (8.2% vs 1.6%) and stunted at three and six months (44.9% vs 3.96%; 20.9% vs 4.84%) when compared to their HEU counterparts. Other South African studies have also reported a high prevalence of stunting in children (28.5%) [21, 22]. Although a larger proportion of the HU infants were breastfed for less than six months, stunting and being underweight were independent of breastfeeding duration. The occurrence of stunting even among the longer breastfed infants is suggestive of other factors that could contribute to the high prevalence of stunting such as mixed feeding or poor quality of breastmilk as a result of poor nutrition in lactating mothers [23, 24]. More recent studies have underscored the role of maternal nutrition among lactating mothers [25, 26]. Maternal nutrition supplementation preconception or early pregnancy was shown to improve linear growth in infants in the first six months, suggesting that poor nutrition in lactating mothers could influence infant growth despite optimal breastfeeding practice [25, 26].

We report significantly lower median WLZ scores among HEU infants at three, six and nine months and WAZ score at nine months in comparison to HU infants and independent of breastfeeding duration. Poor growth has long been associated with HIV exposure; however, nutrition and socioeconomic status have also been considered as significant determinants. In a cross-sectional study in Botswana where HEU infants were more likely to have been formula-fed, a higher proportion of HEU infants between six and 24 months was underweight and stunted underscoring the benefits of breastfeeding [27]. However, even if breastfeeding is the norm, in the slums of Nairobi, Kenya stunting was the most common form of undernutrition among HEU infants when compared to their HU counterparts [28]. The authors concluded that high undernutrition among HEU infants was as a result of HIV exposure, the number of children in a household and the lack of food aid [28]. Here again, we raise the question of nutrition among lactating mothers. Consistent with our findings, a Ugandan study conducted in the pre-ART era also concluded that duration of breastfeeding was not associated with adverse growth outcomes in HEU infants [29]. No matter how long women breastfed, if nutritionally compromised themselves, they are more likely to provide inadequate nutrition to their infants via breastfeeding [25, 26].

After adjusting for breastfeeding duration, we have shown that HEU infants were 2.9, 7.1, 3.0 and 8.9 times at risk of wasting, skin rash, URTI, or any clinical adverse event respectively when compared to their HU counterparts. Consistent with other studies in the pre-ART era, HIV exposure was independently associated with a higher frequency of any clinical event in early infancy. The largest HIV-exposed, uninfected cohort (ZVITAMBO), which prospectively followed up 14 110 infants in Zimbabwe before the availability of ART, reported higher morbidity and three times higher mortality in HEU infants when compared to HU infants; this mortality risk was higher in the first year of life compared with the second [30]. A study in South Africa after universal ART became available, reported significantly more hospitalisations, five times higher prevalence of lower respiratory tract infections and three times higher diarrhoeal diseases in HEU infants compared to HU infants (n = 410) [31]. The higher incidence was attributed to advanced maternal HIV disease and late ART initiation.

Conclusion

Our study has generated additional evidence that infants exposed to HIV are at substantial risk of infectious morbidity and decreased growth trajectories independent of breastfeeding duration. We further report shorter breastfeeding duration in infants not exposed to HIV. And the higher prevalence of stunting in this cohort is also independent of breastfeeding duration.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. We accept that non-contemporaneous studies are not ideal, but this was the only opportunity to disentangle the effect of ART from HIV on infant growth outcomes. To reduce the selection bias, we selected the HEU cohort specifically enrolled from the same community as the HU cohort but only a few years apart. There is much evidence supporting the association between HIV infection and preterm birth, and in addition infants born preterm are also more likely to have poor growth trajectories regardless of birthweight. Unfortunately, we were unable to adjust our analysis for preterm births as gestational age data were not collected.

The high attrition rate of HU infants at three (32%), six (57%) and nine (69%) months was not unusual at the primary health clinic. As a result, we acknowledge that our findings at nine months are not conclusive due to the small number of HU infants assessed at this time point. Another limitation to our study findings is the lack of breastfeeding quality data and maternal nutritional status.

Implications of our findings

The findings presented in this study raise concerns on maternal nutrition irrespective of HIV exposure in SSA. The possible interplay of maternal nutrition, the role of maternal nutrition supplements preconception or in early pregnancy must be considered when developing breastfeeding policies for HIV unexposed, and HIV exposed mother-infant pairs. There is a need for other studies exploring maternal nutrition in association with breastmilk content and infant clinical and growth outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- LMIC:

-

Low and Middle Income Country

- HEU:

-

HIV Exposed Uninfected

- HU:

-

HIV Unexposed

- WLZ:

-

Weight-for-length Z score

- LAZ:

-

Length-for-age Z score

- WAZ:

-

Weight-for-age Z score

- AGE:

-

Acute gastroenteritis

- URTI:

-

Upper respiratory tract infection

- LRTI:

-

Lower respiratory tract infection

- SSA:

-

Sub Saharan Africa

- SA:

-

South Africa

- PMTCT:

-

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission

- cART:

-

Combination antiretroviral treatment

- WLHIV:

-

Women living with HIV

- WNLHIV:

-

Women not living with HIV

- NVP:

-

Nevirapine

References

UNAIDS. Global HIV Statistics 2019. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet. Accessed 05 May 2020.

Slogrove AL, Powis KM, Johnson LF, Stover J, Mahy M. Estimates of the global population of children who are HIV-exposed and uninfected, 2000–18: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(1):e67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30448-6.

UNAIDS. Getting to zero: HIV in eastern and southern Africa. Johannesburg 2013. https://www.unicef.org/esaro/Getting-to-Zero-2013.pdf Accessed 09 May 2020.

Department of Health, South Africa. National Consolidated Guidelines for the Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the Management of HIV in Children, Adolescents and Adults. 2015 www.health.gov.za. Accessed 16 May 2020.

Cohen C, Moyes J, Tempia S, Groome M, Walaza S, Pretorius M, et al. Epidemiology of acute lower respiratory tract infection in HIV-exposed uninfected infants. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20153272. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3272.

Brennan AT, Bonawitz R, Gill CJ, Thea DM, Kleinman M, Long L, et al. A meta-analysis assessing diarrhea and pneumonia in HIV-exposed uninfected compared with HIV-unexposed uninfected infants and children. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;82(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002097.

Marquez C, Okiring J, Chamie G, Ruel TD, Achan J, Kakuru A, et al. Increased morbidity in early childhood among HIV-exposed uninfected children in Uganda is associated with breastfeeding duration. J Trop Pediatr. 2014;60(6):434–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmu045.

Child Healthcare Problem Identification Programme (ChIP), https://www.kznhealth.gov.za/chrp/CHIP.html. Accessed 25 Sep 2020.

Sankar MJ, Sinha B, Chowdhury R, Bhandari N, Taneja S, Martines J, et al. Optimal breastfeeding practices and infant and child mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(467):3–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13147.

Feachem RG, Koblinsky MA. Interventions for the control of diarrhoeal diseases among young children: promotion of breastfeeding. Bull World Health Organ. 1984;62(2):271–91.

WHO. Infant and Young Child Feeding. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding Accessed 10 May 2020.

Arikawa S, Rollins N, Jourdain G, Humphrey J, Kourtis AP, Hoffman I, et al. Contribution of maternal antiretroviral therapy and breastfeeding to 24-month survival in human immunodeficiency virus-exposed uninfected children: an individual pooled analysis of African and Asian studies. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(11):1668–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix1102.

Horwood C, Haskins L, Engebretsen I, Connolly C, Coutsoudis A, Spies L. Are we doing enough? Improved breastfeeding practices at 14 weeks but challenges of non-initiation and early cessation of breastfeeding remain: findings of two consecutive cross-sectional surveys in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):440. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08567-y.

Zunza M, Esser M, Slogrove A, Bettinger JA, Machekano R, Cotton MF. Mother-infant health study (MIHS) project steering committee. Early breastfeeding cessation among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in Western Cape Province, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(Suppl 1):114–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2208-0.

Ramokolo V, Goga AE, Lombard C, Doherty T, Jackson DJ, Engebretsen IM. In Utero ART Exposure and Birth and Early Growth Outcomes Among HIV-Exposed Uninfected Infants Attending Immunisation Services: Results From National PMTCT Surveillance, South Africa. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017; 4: ofx187. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofx187.

le Roux SM, Abrams EJ, Donald KA, Brittain K, Phillips TK, Nguyen KK, Zerbe A, Kroon M, Myer L. Growth trajectories of breastfed HIV-exposed uninfected and HIV-unexposed children under conditions of universal maternal antiretroviral therapy: a prospective study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2019;3(4):234–244. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30007-0. Epub 2019.

Coovadia HM, Brown ER, Fowler MG, Chipato T, Moodley D, Manji K, et al. Efficacy and safety of an extended nevirapine regimen in infant children of breastfeeding mothers with HIV-1 infection for prevention of postnatal HIV-1 transmission (HPTN 046): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9812):221–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61653-X.

CAP088 Study. HIV incidence rates, socio-behavioural and biological HIV risk factors, HIV transmission rates and acceptability of PreP during pregnancy and/or post-natally in KwaZulu-Natal. https://www.caprisa.org/Pages/CAPRISAStudies Accessed 10 May 2020.

WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group (2006). WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, Weight-for-Age, Weight-for- Length, Weight-for-Height and Body Mass Index-for-Age: Methods and Development Geneva: World Health Organization; 312 Available at: www.hoint/childgrowth/publication Accessed 10 May 2020.

World Health Organisation (2010). Nutrition Landscape Information System (NLIS) Available at https://www.who.int/nutrition/nlis_interpretation_guide.pdf Accessed 20 May 2020.

Rothman M, Faber M, Covic N, Matsungo TM, Cockeran M, Kvalsvig JD. Smuts C infant development at the age of 6 months in relation to feeding practices, Iron status, and growth in a Peri-Urban Community of South Africa. Nutrients. 2018;10(1):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10010073.

Matsungo TM, Kruger HS, Faber M, Rothman M, Smuts CM. The prevalence and factors associated with stunting among infants aged 6 months in a peri-urban south African community. Public Health Nutr 2017 Dec;20(17):3209–3218. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017002087. Epub 2017 Sep 7.

Lutter CK, Daelmans BM, de Onis M, Kothari MT, Ruel MT, Arimond M, Deitchler M, Dewey KG, Blössner M, Borghi E. Undernutrition, poor feeding practices, and low coverage of key nutrition interventions. Pediatrics. 2011; 128(6): e1418-e1427. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1392. Epub 2011 Nov 7.Pediatrics. 2011. PMID: 22065267

Fouché C, van Niekerk E, du Plessis LM. Differences in breast Milk composition of HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected mothers of premature infants: effects of antiretroviral therapy. Breastfeed Med 2016 Nov;11:455–460. doi: https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2016.0087. Epub 2016 Aug 16. PMID: 27529566, 9.

Krebs NF, Hambidge KM, Westcott JL, Garcés AL, Figueroa L, Tsefu AK, et al. Women First Preconception Maternal Nutrition Study Group. Growth from Birth through Six Months for Infants of Mothers in the “Women First” Preconception Maternal Nutrition Trial. J Pediatr. 2020: S0022–S3476(20)31165–3. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.09.032.

Kerac M, Mwangome M, McGrath M, Haider R, Berkley JA. Management of acute malnutrition in infants aged under 6 months (MAMI): current issues and future directions in policy and research. Food Nutr Bull. 2015;36(1_suppl):S30–S4.

Chalashika P, Essex C, Mellor D, Swift JA, Langley-Evans S. Birthweight, HIV exposure and infant feeding as predictors of malnutrition in Botswanan infants. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2017;30(6):779–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12517.

Wambura JN, Marnane B. Undernutrition of HEU infants in their first 1000 days of life: a case in the urban-low resource setting of Mukuru slum, Nairobi, Kenya. Heliyon. 2019;5(7):e02073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.

Muhangi L, Lule SA, Mpairwe H, Ndibazza J, Kizza M, Nampijja M, et al. Maternal HIV infection and other factors associated with growth outcomes of HIV-uninfected infants in Entebbe, Uganda. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(9):1548–57. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980013000499.

Marinda E, Humphrey JH, Iliff PJ, Mutasa K, Nathoo KJ, Piwoz EG, et al. Child mortality according to maternal and infant HIV status in Zimbabwe. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(6):519–26. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000264527.69954.

le Roux SM, Abrams EJ, Donald KA, Brittain K, Phillips TK, Zerbe A, et al. Infectious morbidity of breastfed, HIV-exposed uninfected infants under conditions of universal antiretroviral therapy in South Africa: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(3):220–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30375-X.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the HPTN046 and CAP088 protocol teams for allowing us access to the data. We also thank the Umlazi study co-ordinators, data management, laboratory and clinical teams that conducted the HPTN046 and CAP088 studies.

Funding

The HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 046 study was funded by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), initially through the HPTN and later through the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials (IMPAACT) group. The HPTN (U01AI46749) has been funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), and National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). NIAID, NICHD, and NIMH have funded the IMPAACT Group (U01AI068632). The CAP088 study was funded by Family Health International 360 under Cooperative Agreement/Grant No. AID-674-A-14-00009 funded by USAID Southern Africa. CAPRISA provided additional funding for this study. None of these funding bodies contributed to the design of the study, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data and writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LP conceptualised the study, collated the data, interpreted the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. DM and KN assisted with conceptualising the study, interpretation of statistical analysis and helped write the manuscript. LME assisted with data collation and reviewed the manuscript. NMN performed the statistical analysis and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board of University of KwaZulu-Natal approved the study (Ref BE 643/16 sub-study of BE 616/16). In this retrospective data analysis, participant consent was not obtained, and we used de-identified data.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare no conflict of interests related to this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pillay, L., Moodley, D., Emel, L.M. et al. Growth patterns and clinical outcomes in association with breastfeeding duration in HIV exposed and unexposed infants: a cohort study in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. BMC Pediatr 21, 183 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02662-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02662-8