Abstract

Background

The first 1000 days of life are a critical period when the foundations of child development and growth are established. Few studies in Latin America have examined the relationship of birth outcomes and neonatal care factors with development outcomes in young children. We aimed to assess the association between pregnancy and neonatal factors with children’s developmental scores in a cross-sectional, population-based study of children in Ceará, Brazil.

Methods

Population-based, cross-sectional study of children aged 0–66 months (0–5.5 years) living in Ceará, Brazil. We examined the relationship of pregnancy (iron and folic acid supplementation, smoking and alcohol consumption) and neonatal (low birth weight (LBW) gestational age, neonatal care interventions, and breastfeeding in the first hour) factors with child development. Children’s development was assessed with the Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ-BR). We used multivariate generalized linear models that accounted for clustering sampling to evaluate the relationship of pregnancy and neonatal factors with development domain scores.

Findings

A total of 3566 children were enrolled. Among pregnancy factors, children whose mothers did not receive folic acid supplementation during pregnancy had lower fine motor and problem-solving scores (p-values< 0.05). As for neonatal factors, LBW was associated with 0.14 standard deviations (SD) lower (CI 95% -0.26, − 0.02) communication, 0.24 SD lower (95% CI: − 0.44, − 0.04) fine motor and 0.31 SD lower (CI 95% -0.45, − 0.16) problem-solving domain scores as compared to non-LBW children (p values < 0.05). In terms of care, newborns that required resuscitation, antibiotics for infection, or extended in-patient stay after birth had lower development scores in selected domains. Further, not initiating breastfeeding within the first hour after birth was associated with lower gross motor and person-social development scores (p-values < 0.05).

Conclusion

Pregnancy and neonatal care factors were associated with later child development outcomes. Infants at increased risk of suboptimal development, like LBW or newborns requiring extended in-patient care, may represent groups to target for supplemental intervention. Further, early integrated interventions to prevent adverse pregnancy and newborn outcomes may improve child development outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It is estimated that over 250 million children under the age of 5 years in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) do not reach their full developmental potential [1]. The first 1000 days of life, from conception to the second birthday, are critical for children’s development due to rapid brain development [2] and early child development is a determinant of later-life academic achievement and human capital outcomes [3,4,5].

Child development can be affected by a combination of socioeconomic, environmental, nutritional, and social factors during pregnancy and the first years of life [2, 6]. Studies in both high-income and LMIC have identified multiple factors associated poverty are associated with suboptimal development, low maternal level of schooling, suboptimal breastfeeding, and lack of responsive caregiving [6,7,8]. Further adverse birth outcomes, including low birth weight (LBW; < 2500 g) have been reported to be associated with suboptimal development outcomes. Additionally, developmental delays may be found in as many as 50% of children born with very low birth weight (VLBW; < 1500 g) [9,10,11,12]. The LBW prevalence in Brazil in 2015 was 10.1% [13].

Nevertheless, very few large, population-based studies have assessed the association of pregnancy and neonatal care factors with development outcomes in newborns, infants, toddlers, and preschoolers, particularly in the context of Latin American [14]. In addition, a recent systematic review determined that data on the association between delivery and neonatal characteristics with child development outcomes are lacking [15].

We assessed the association of pregnancy and neonatal factors with communication, gross-motor, fine-motor, problem-solving, and personal-social developmental scores.. These observational evidence are intended to inform populations at risk for suboptimal development and for design of interventions to improve development outcomes.

Methods

Study design and population

We analyzed data from the Pesquisa de Saúde Materno Infantil no Ceará (PESMIC, Maternal and Child Health Survey in Ceará) and full details about the parent study methods and the child development assessment can be found elsewhere [16, 17]. Briefly, the PESMIC is a population-based, cross-sectional study on maternal and child health carried out in preschool children, aged 0 to 72 months, living in the state of Ceará, in northeastern Brazil. Ceará is one of Brazil’s poorest states, with a population of 9 million inhabitants living in a semiarid climate. Fortaleza (2.3 million inhabitants) is the capital city and urban commercial center of Ceará. The study area also includes rural areas of the state, where subsistence farming is the dominant type of agricultural activity.

PESMIC surveys were conducted in 1987, 1990, 1994, 2001, 2007, and 2017 using the same methods. For this analysis, we used child development data from the 2017 PESMIC survey, conducted from August to November 2017. The PESMICs used cluster sampling, based on the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) census tracts, and stratification between the state capital city of Fortaleza, and the rural areas. The 2017 PESMIC surveyed 160 randomly selected census tracts, including 3200 households. Once a census tract was defined and its corresponding map obtained, the location of the cluster of 20 houses to be investigated was determined as follows: the starting point of the cluster (the first home to be visited) was randomly selected utilizing ArcGIS® software, GIS Inc. Households were visited consecutively, in a counterclockwise spiral fashion. Shops and abandoned buildings were excluded and replaced, and in the case of absent families, up to three return visits were made to obtain data. In each household, information was obtained about all children through the mother’s or primary caregiver’s report (97.2% were mothers). All data were collected on paper forms and were double-entered using the software EpiInfo™ 2000 (used only for data entry).

Child development assessment

Child development was assessed using the Ages and Stages Questionnaire version 3 [18], a screening tool for child development delays, which has been validated in Brazil (ASQ-BR) [19]. Child development was only assessed for participants aged 0 to 66 months since the ASQ has only been validated in this age group. Five child development domains were measured in the ASQ-BR: communication, broad motor coordination, fine motor coordination, problem-solving, and personal-social skills [18]. The interviewers were trained on the use of the ASQ-BR for 20 h by medical professionals. In terms of scoring, a child’s domain score was considered invalid and considered missing if more than two items were skipped. The ASQ was administered to mothers/caregivers by trained interviewers and by direct observation of the child. If one or two items in one area were skipped, we provided an adjusted score by calculating the average score for the completed items in that area and attributed the average score to the missed item [18]. Age-standardized scores were calculated, and adjustments were made for children aged less than 24 months and who were born preterm by subtracting the number of weeks of prematurity from the child’s chronological age and then using this number to determine the appropriate ASQ questionnaire to be administered [18].

Exposures of interest

In Brazil, all children receive a child health booklet at birth, in which health professionals record health information about the antenatal care, delivery, vaccination, and child growth and development. We used these data to evaluate birth weight and gestational age at birth. Low birth weight was defined as children born weighing less than 2500 g. At birth, gestational age was collected from the child health booklet and is usually estimated from the first obstetric ultrasound. Preterm was defined as less than 37 completed weeks gestation. Delivery care factors were also recorded in the booklet.

Standardized questionnaires were administered to the mother or head of the household. Prenatal (including life habits variables), delivery, and birth data were reported by the mother and confirmed by the child health booklet. When maternal reports and the booklet data were divergent, the health booklet data were preferentially selected.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed age- and sex-standardized ASQ-BR scores [20] for children aged 5 months or older. For children younger than 5 months, we used US ASQ standards due to the lack of Brazilian standardized scores for young infants under 5 months of age [21]. First, the descriptive statistics are presented, adjusting for clustering by design. We used generalized linear models to determine the association of pregnancy, delivery, and postnatal factors with the ASQ-BR domain scores. We present standardized mean differences (SMD) to compare effect sizes to other studies. We took a causal approach to the multivariate analyses, which were minimally adjusted for age, sex, income, and interviewer, then fully adjusted models including common causes (confounders) of the exposures of interest and development outcomes. To avoid adjusting for potential downstream mediators, pregnancy models did not adjust for birth outcome and postnatal factors. We also examined potential effect modification of the association of LBW with child development outcomes based on biological plausibility. We used pairwise deletion to account for missing data. All study data were analyzed using SPSS, Version 23 (SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. IBM Inc).

Ethical aspects

Written informed consent was obtained from the participating women. The caregivers also provided written permission for their child’s participation in the study, and consent for mothers who were adolescent minors was obtained from their parents or legal guardians. The Research Ethics Committee in Brazil approved the PESMICs survey under number 73516417.4.0000.5049.

Results

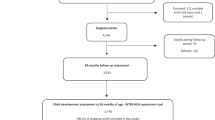

The study included a cross-sectional population-based sample of 3566 children from 3200 households. A summary of the study population characteristics is presented in Table 1. The mean child age was 31.8 ± 23.1 months, and the sample was equally distributed between males and females. The mean maternal schooling attainment was 4.4 ± 2.8 years, and the mean income was R$1090.4 (~ 280 USD) ±1017.9 reais per household. Among children in the sample, 7.7% were born LBW and 10.4% were born preterm (< 37 weeks). Almost all women reported taking iron and folic acid supplements during the pregnancy, while 6% reported smoking or drinking during the pregnancy. A total of 525 children (14%) required extended in-hospital stay after birth, and 5% required antibiotics in the immediate postnatal period. A total of 79.2% of children were breastfed within the first hour of life.

The association between pregnancy factors, LBW and prematurity with child development outcomes is shown in Table 2. In a multivariate analysis, not reporting prenatal folic acid supplementation was associated with lower fine-motor and problem-solving domain scores (p values < 0.01). LBW was also associated with lower communication (standardized mean difference (SMD): -0.14; 95% CI -0.26, − 0.02), fine motor (SMD: -0.24;95% CI -0.44, − 0.04) and problem-solving (SMD: -0.31; 95% CI -0.45, − 0.16) domain scores (p values < 0.05), after adjustment for the child’s age, sex, income, pregnancy factors and gestational age.

The relationship of neonatal care factors with development outcomes is shown in Table 3. Extended in-patient stays in NICU or incubator after birth was also independently associated with lower communication, gross motor, fine motor, and problem-solving domains, after adjusting for LBW (p-values < 0.05). In addition, newborns that received resuscitation had − 0.43 (95% CI -0.83, − 0.03) and − 0.78 (95% CI: − 1.30, − 0.25) SD lower communication and fine-motor developmental scores, respectively. Antibiotic use, a proxy of neonatal infection, was associated with poorer fine motor (SMD: -0.32; 95% CI: − 0.6, − 0.05) and problem-solving (SMD: -0.28; 95% CI: − 0.5, − 0.07). In multivariate models, not initiating breastfeeding within the first hour after birth was associated with − 0.30 SD (95% CI: − 0.51, − 0.09) lower gross motor and − 0.21 SD (95% CI: − 0.37, − 0.06) lower personal-social domain scores as compared to infants who initiated breastfeeding within the first hour after birth.

The potential interaction of LBW with child age was also assessed (Table 4). In Fig. 1 is presented that the magnitude of the negative association of LBW with the problem-solving and personal-social domain scores was greater in magnitude for younger children (≤1 year) as compared to toddlers and preschoolers (p-values for the interaction < 0.05).

Discussion

In this population-based survey conducted in Ceará, Brazil, we found that pregnancy and neonatal care factors were associated with development outcomes. In terms of pregnancy factors, children whose mothers did not receive folic acid supplementation during pregnancy had lower fine motor and problem-solving scores. LBW was associated with lower communication, fine-motor, and problem-solving scores. We also found the magnitude of the negative association for LBW was greater for infants as compared to older children for problem-solving and personal-social domain scores. In terms of neonatal care, need for resuscitation, antibiotic use by the newborn, and extended in-patient stay after birth was associated with lower development scores in selected domains. Initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour of life was associated with better gross motor and personal-social domains scores.

In terms of pregnancy factors, we found that not receiving folic acid supplementation during pregnancy was associated with large (> 0.5) deficits in the fine motor and problem-solving scores. Folate is essential in the formation of the neural tube [22]. It is also necessary for the production of RNA and DNA precursors, and low folate levels can result in abnormalities in cell proliferation, including for neuron production, and can contribute to DNA instability and chromosome breakage [23]. A recent observational study in China found that children whose mothers took folic acid supplements during pregnancy had significantly higher development quotient (DQ) at 1 month of age as compared to children whose mothers did not take folic acid [24]. Further, another study found that maternal serum folate concentration in late pregnancy was significantly associated with higher language development scores at 2 years of age [25]. As a result, our study adds to the growing observational evidence base that folic acid supplementation in pregnancy may improve development outcomes.

The prevalence of LBW and preterm birth found in this study is comparable with rates found in other Brazilian studies, and government data for Ceará in the year 2017 which recorded 8.2% LBW [26, 27]. There is a robust literature linking LBW to increased risk of suboptimal development outcomes, and some research has suggested that that language development may be the most affected domain [28, 29]. Many studies have identified that this association of LBW with development scores persists among school-age children and even into adulthood [10, 13]. It is estimated that approximately 25–50% of LBW infants have brain abnormalities associated with cognitive, behavioral, attentional, and socialization impairment [30, 31]. In this study, we found that LBW was a risk factor for suboptimal development for children up to 5 years of age. However, we found that the magnitude of the association tended to be greater for younger ages. This finding may be due to evidence of the developmental ‘catch up’ of the LBW children, which has been seen in other studies, in which LBW children aged 2 years of age and older would start to catch up with the rest of age-matched peers [32].

There are several mechanisms by which LBW may have an impact on child development. The process starts from the intrauterine formation of neuronal connections and extends after birth, implying a different growth of the corpus callosum, cerebral volume, and cortical thickness [31]. LBW may be the result of prematurity and intrauterine growth restriction. We found that LBW was associated with impaired development independently of gestational age, but some of its effects may follow a pathway close to that of prematurity. Premature infants can have conditions like periventricular leukomalacia and accompanying neuronal/axonal abnormalities (common, occurring in 50% or more of very LBW infants < 2000 g); severe germinal matrix-intraventricular hemorrhage, and post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus, which may directly affect development outcomes [33]. Besides, infants may be LBW due to intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), indicating constraints in fetal nutrition that may lead to suboptimal development [34]. The evidence on the relationship of small-for-gestational-age newborns with development outcomes is mixed [35]. Besides the direct biological constraints due to prematurity and SGA, LBW infants have an increased need for parental care that may contribute to maternal stress, depression, and other factors that can lead to poorer child development outcomes [36]. In addition to the mechanisms mentioned earlier, children born with LBW have less ability to concentrate and impaired personal-social personal skills, as also seen in this study. This compromised social competence can generate a vicious circle of worsening in the development of older children [37]. Interventions to reduce the risk of LBW may have significant effects on developmental outcomes and programs to support the growth and development of preterm and LBW infants.

Few studies have assessed the association between neonatal care factors and developmental outcomes in low-income settings. After adjusting for LBW, we found that extended in-patient stays in the NICU or incubator after birth was associated with impaired communication, gross motor, and fine motor development. We also found that the need for resuscitation and antibiotic use after birth were independently associated with lower scores in communication and problem-solving domains and problem-solving and personal-social domains, respectively. The need for resuscitation can be considered a proxy of hypoxia, which can lead to brain injury and developmental impairment [38]. Neonatal infections, including sepsis, may have long-term effects on child developmental outcomes [39]. As a result, stimulation interventions and educational programs may consider targeting children who require extended in-hospital stays, require resuscitation, or have neonatal infections due to their risk for suboptimal developmental outcomes later in life, regardless of the birth weight.

Finally, we also found that breastfeeding initiation within the first hour of life was associated with improved gross motor and personal-social development. Breastfeeding within the first hour of life has a protective effect on neonatal mortality and morbidity; however, there is little evidence of its impact on developmental outcomes [40, 41]. It has also been associated with increased bonding between the newborn and the mother through increased skin-to-skin contact, promoting continued breastfeeding, and maybe a protective factor in LBW children, and thus, it should be encouraged [42].

This study is one of the first evaluations of the association between LBW and children’s development in a pediatric sample with a broad age range in a developing country, with a state-wide representative sample. Nevertheless, this study has a few limitations. First, the study’s cross-sectional design does not allow the analysis of child development trajectories over time, nor directs the determination of causal associations and recall bias can impact information in older children. Second, we used the ASQ-3, a validated screening tool that allows child development evaluation in a large populational sample, but which is not a diagnostic tool for child developmental delay. Furthermore, while the study was designed to represent a pediatric population in the State of Ceará, our findings may not be generalizable to children in other contexts.

Conclusions

We determined that pregnancy and neonatal factors were associated with child development in a population-based study in Ceara, Brazil. We found that lack of folic acid supplementation in pregnancy, LBW, newborn resuscitation, newborn receipt of antibiotics and extended in-patient stays were risk factors for suboptimal development outcomes in selected domains. As a result, these findings suggest these high-risk groups may benefit from supplemental interventions, such as LBW or infants requiring extended in-patient stay. However, it is important to note that integrated interventions to prevent adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes may also have positive effects on child development. Research on population-based interventions to improve child development in Brazil is warranted.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- LBW:

-

Low Birth Weight

- SGA:

-

Small for gestational age

- PESMIC:

-

Pesquisa de Saúde Materno Infantil do Ceará

- IBGE:

-

Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics

- USDA:

-

United States Department of Agriculture

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- L.M.I.C.:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- S.D.G.:

-

Sustainable development goals

- NICU:

-

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

References

Lu C, Black MM, Richter LM. Risk of poor development in young children in low-income and middle-income countries: an estimation and analysis at the global, regional, and country level. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(12):e916–e22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30266-2.

Shonkoff JP, Boyce WT, McEwen BS. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA. 2009;301(21):2252–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.754.

Grantham-McGregor S, Cheung YB, Cueto S, Glewwe P, Richter L, Strupp B. Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. Lancet. 2007;369(9555):60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60032-4.

Fink G, Peet E, Danaei G, Andrews K, McCoy DC, Sudfeld CR, et al. Schooling and wage income losses due to early-childhood growth faltering in developing countries: national, regional, and global estimates. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104(1):104–12. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.123968.

Smith JP. The impact of childhood health on adult labor market outcomes. Rev Econ Stat. 2009;91(3):478–89. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.91.3.478.

Walker SP, Wachs TD, Grantham-McGregor S, Black MM, Nelson CA, Huffman SL, et al. Inequality in early childhood: risk and protective factors for early child development. Lancet. 2011;378(9799):1325–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60555-2.

Phillips DA, Shonkoff JP. From neurons to neighborhoods: the science of early childhood development: National Academies Press; 2000.

Sudfeld CR, McCoy DC, Fink G, Muhihi A, Bellinger DC, Masanja H, et al. Malnutrition and its determinants are associated with suboptimal cognitive, communication, and motor development in Tanzanian children. J Nutr. 2015;145(12):2705–14. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.115.215996.

Oudgenoeg-Paz O, Mulder H, Jongmans MJ, van der Ham IJM, Van der Stigchel S. The link between motor and cognitive development in children born preterm and/or with low birth weight: a review of current evidence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;80:382–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.06.009.

Hack M, Klein NK, Taylor HG. Long-term developmental outcomes of Low birth weight infants. Futur Child. 1995;5(1):176–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/1602514.

Halpern R, Barros AJ, Matijasevich A, Santos IS, Victora CG, Barros FC. Developmental status at age 12 months according to birth weight and family income: a comparison of two Brazilian birth cohorts. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24(suppl 3):s444–s50. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2008001500010.

Larroque B, Ancel PY, Marret S, Marchand L, André M, Arnaud C, et al. Neurodevelopmental disabilities and special care of 5-year-old children born before 33 weeks of gestation (the EPIPAGE study): a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2008;371(9615):813–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60380-3.

Silveira MF, Victora CG, Horta BL, da Silva BGC, Matijasevich A, Barros FC. Low birthweight and preterm birth: trends and inequalities in four population-based birth cohorts in Pelotas, Brazil, 1982–2015. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;48(Supplement_1):i46–53.

Blencowe H, Krasevec J, de Onis M, Black RE, An X, Stevens GA, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of low birthweight in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(7):e849–e60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30565-5.

Vaivada T, Gaffey MF, Bhutta ZA. Promoting early child development with interventions in health and nutrition: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2017;140(2):e20164308. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-4308.

Correia LL, Rocha HAL, Rocha SGMO, LSd N, ACe S, Campos JS, et al. Methodology of maternal and child health populational surveys: a statewide cross-sectional time series carried out in ceará, brazil, from 1987 to 2017, with pooled data analysis for child stunting. Ann Glob Health. 2019;85:1.

Correia LL, Rocha HAL, Sudfeld CR, Rocha SGMO, Leite ÁJM, Campos JS, et al. Prevalence and socioeconomic determinants of development delay among children in Ceará, Brazil: a population-based study. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0215343. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215343.

Squires J, Bricker DD, Twombly E. Ages & stages questionnaires. Paul H. Brookes Baltimore, MD; 2009.

Filgueiras A, Landeira-Fernandez J. Adaptação transcultural e avaliação psicométrica do Ages and Stages Questionnaires (ASQ) em creches públicas da cidade do Rio de Janeiro: Psicologia, PUC--Rio Rio de Janeiro: PUC-Rio; 2011.

Filgueiras A, Pires P, Maissonette S, Landeira-Fernandez J. Psychometric properties of the Brazilian-adapted version of the ages and stages questionnaire in public child daycare centers. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89(8):561–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2013.02.005.

Janson H, Squires J. Parent-completed developmental screening in a Norwegian population sample: a comparison with US normative data. Acta Paediatr. 2004;93(11):1525–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/08035250410033051.

Milunsky A, Jick H, Jick SS, Bruell CL, MacLaughlin DS, Rothman KJ, et al. Multivitamin/folic acid supplementation in early pregnancy reduces the prevalence of neural tube defects. JAMA. 1989;262(20):2847–52. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1989.03430200091032.

Frye RE, Sequeira JM, Quadros EV, James SJ, Rossignol DA. Cerebral folate receptor autoantibodies in autism spectrum disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;18:369.

Yan J, Zhu Y, Cao L-J, Liu Y-Y, Zheng Y-Z, Li W, et al. Effects of maternal folic acid supplementation during pregnancy on infant neurodevelopment at 1 month of age: a birth cohort study in China. Eur J Nutr. 2020;59(4):1345–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-019-01986-7.

Huang X, Ye Y, Li Y, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Jiang Y, et al. Maternal folate levels during pregnancy and children’s neuropsychological development at 2 years of age. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2020;74(11):1585–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-020-0612-9.

Zerbeto AB, Cortelo FM, Filho ÉBC. Association between gestational age and birth weight on the language development of Brazilian children: a systematic review. J Pediatr. 2015;91(4):326–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2014.11.003.

BRASIL. Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde (Datasus). http://www2.datasus.gov.br/ (2018). Accessed 15/01/2021 2021.

Lee H, Barratt MS. Cognitive development of preterm low birth weight children at 5 to 8 years old. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1993;14(4):242–9.

Kline JE, Illapani VSP, He L, Altaye M, Logan JW, Parikh NA. Early cortical maturation predicts neurodevelopment in very preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2019;107(Suppl 1):i60.

Bayless S, Stevenson J. Executive functions in school-age children born very prematurely. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83(4):247–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2006.05.021.

Sripada K, Bjuland KJ, Sølsnes AE, Håberg AK, Grunewaldt KH, Løhaugen GC, et al. Trajectories of brain development in school-age children born preterm with very low birth weight. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):15553. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33530-8.

Dale PS, Greenberg MT, Crnic KA. The multiple determinants of symbolic development: evidence from preterm children. New Dir Child Dev. 1987;36:69–86.

Volpe JJ. The encephalopathy of prematurity—brain injury and impaired brain development inextricably intertwined. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2009;16(4):167–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spen.2009.09.005.

Walker SP, Wachs TD, Meeks Gardner J, Lozoff B, Wasserman GA, Pollitt E, et al. Child development: risk factors for adverse outcomes in developing countries. Lancet. 2007;369(9556):145–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60076-2.

Sania A, Sudfeld CR, Danaei G, Fink G, McCoy DC, Zhu Z, et al. Early life risk factors of motor, cognitive and language development: a pooled analysis of studies from low/middle-income countries. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):e026449. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026449.

McCormick MC, Gortmaker SL, Sobol AM. Very low birth weight children: behavior problems and school difficulty in a national sample. J Pediatr. 1990;117(5):687–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3476(05)83322-0.

Alduncin N, Huffman LC, Feldman HM, Loe IM. Executive function is associated with social competence in preschool-aged children born preterm or full term. Early Hum Dev. 2014;90(6):299–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2014.02.011.

Low JA, Galbraith R, Muir D, Killen H, Pater E, Karchmar E. Factors associated with motor and cognitive deficits in children after intrapartum fetal hypoxia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;148(5):533–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(84)90742-7.

Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Adams-Chapman I, Fanaroff AA, Hintz SR, Vohr B, et al. Neurodevelopmental and growth impairment among extremely low-birth-weight infants with neonatal infection. JAMA. 2004;292(19):2357–65. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.19.2357.

Vieira TO, Vieira GO, Giugliani ERJ, Mendes CM, Martins CC, Silva LR. Determinants of breastfeeding initiation within the first hour of life in a Brazilian population: cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):760. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-760.

UNICEF, WHO. Capture the moment: early initiation of breastfeeding: the best start for every newborn. UNICEF. 2018.

Oras P, Thernstrom Blomqvist Y, Hedberg Nyqvist K, Gradin M, Rubertsson C, Hellstrom-Westas L, et al. Skin-to-skin contact is associated with earlier breastfeeding attainment in preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 2016;105(7):783–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13431.

Acknowledgments

To all the study participants and especially to all mothers who, sometimes even under unfavorable environmental, emotional and/or social conditions agreed to tell us their stories.

Funding

Fundação Cearense de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico. Public Notice: CHAMADA 07/2013 - PPSUS CE - FUNCAP/SESA/MS/CNPq. Number of grant: 13506703–0.

Fundação Cearense de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico. Public Notice Jovens Doutores – Public Notice n. 02/2017.

These funding sources had no role in the design of this study, execution, analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author’s contributions were as follows: HALR, SGMOR, LLC, Á.J.M.L., JSC, CRS, MMTM, and AC e S. have made substantial contributions to the study conception and design and reviewed the manuscript critically for relevant intellectual content and on drafting the article and they reviewed it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all participating women. Written consent for the children’s participation was also given by the mothers, and consent for adolescent minors was obtained from their parents or legal guardians. The PESMICs survey was approved by the Research Ethics Committee in Brazil, under number 73516417.4.0000.5049.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rocha, H.A.L., Sudfeld, C.R., Leite, Á.J.M. et al. Maternal and neonatal factors associated with child development in Ceará, Brazil: a population-based study. BMC Pediatr 21, 163 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02623-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02623-1