Abstract

Background

Identifying individual characteristics linked with physical activity (PA) and sedentary time (SED) can assist in designing health-enhancing interventions for children. We examined cross-sectional associations of temperament characteristics with 1) PA and SED and 2) meeting the PA recommendation in Finnish children.

Methods

Altogether, 697 children (age: 4.7 ± 0.9 years, 51.6% boys) within the Increased Health and Wellbeing in Preschools (DAGIS) study were included. Parents responded to the Very Short Form of the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire consisting of three temperament dimensions: surgency, negative affectivity, and effortful control. PA and SED were assessed for 7 days (24 h per day) using a hip-worn ActiGraph accelerometer, and the daily minutes spent in light PA (LPA), moderate PA (MPA), vigorous PA (VPA), and SED were calculated. The PA recommendation was defined as having PA at least 180 min/day, of which at least 60 min/day was in moderate-to-vigorous PA. Adjusted linear and logistic regression analyses were applied.

Results

Surgency was associated with LPA (B = 3.80, p = 0.004), MPA (B = 4.87, p < 0.001), VPA (B = 2.91, p < 0.001), SED (B = − 11.45, p < 0.001), and higher odds of meeting the PA recommendation (OR = 1.56, p < 0.001). Effortful control was associated with MPA (B = − 3.63, p < 0.001), VPA (B = − 2.50, p < 0.001), SED (B = 8.66, p < 0.001), and lower odds of meeting the PA recommendation (OR = 0.61, p = 0.004). Negative affectivity was not associated with PA, SED, or meeting the PA recommendation.

Conclusion

Children’s temperament should be considered when promoting PA in preschoolers. Special attention should be paid to children scoring high in the temperament dimension effortful control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Physical activity (PA) has been found to contribute favorably to numerous health indicators in preschool-aged children (3–5 years) [1]. Regular PA has been connected, for example with lower adiposity, improved cardiometabolic health, and better cognitive and motor skills development [1]. Sedentary time (SED), however, has been identified as the fourth leading risk factor for noncommunicable diseases by the World Health Organization (WHO) [2]. In accordance with the WHO’s recently updated PA recommendation, preschool children should spend at least 180 min daily at any PA intensity of which at least 60 min should be moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) [3]. Since only a small proportion of preschool children have been reported to comply with the recommendation [4, 5], further clarification of factors related to the compliance of PA recommendations is warranted. As healthy PA habits are established in early life [6, 7], it is important to pay attention to childhood as a critical period with respect to developing the course of health behaviors. Further, it is important to identify factors that potentially play a role in the effectiveness of health behavior interventions initiated at an early age [8].

Regarding intraindividual factors, temperament has shown to be one of the most essential factors contributing to the development of health behaviors from an early age [9]. Temperament is a biologically based, partly inherited behavioral tendency that comprises the core of one's personality [10,11,12]. Rothbart’s [11] approach emphasizes motor and emotional reactivity as well as attentional processes as regulators of a person’s reactive tendencies. According to this approach [11], the three broad dimensions constitute temperament: 1) surgency (e.g., activity level, sociability, and enjoyment expressed during high-intensity activities), 2) negative affectivity (e.g., anger, sadness, fear, physical discomfort, and recovery from distress), and regulatory capacity in infants and 3) effortful control in older individuals (e.g., ability to focus attention, demonstration of satisfaction during low-intensity activities) [9, 11]. Each of these dimensions may be relevant in the development of health behaviors, such as PA and SED, from an early age [9]. Thus, understanding more deeply temperament’s role in these behaviors may help in supporting children to better manage their potential temperament-related challenges and identify children at higher risk for negative outcomes caused by insufficient PA and increased SED [9]. Furthermore, it is important to recognize the potential benefits of specific behavioral tendencies with respect to the development of a physically active lifestyle. Yet, the existing evidence regarding how the temperamental differences contribute to PA or SED is limited and warrants further research.

To the best of our knowledge, there are only a few previous studies investigating the associations of temperament with PA and SED in preschool-aged children. The majority of the cross-sectional studies have based PA assessment on questionnaires [7,8,9] or has covered only childcare hours [10], leading to inconsistent findings. A longitudinal study by Schmutz et al. [13] covered a whole day and they reported that temperamental activity [referring to the need for moving, the amount of energy an individual uses for his or her actions, and the speed of his or her behaviors [14]] was positively associated with accelerometer-derived total PA and MVPA and negatively associated with SED. However, as the recently updated global PA recommendation includes PA at any intensity [2], there is a need to study associations of temperament with all PA intensities. Such knowledge would benefit professionals in designing and implementing recreational activities that fit each individual’s temperament [12].

The aims of this study were to investigate associations of temperament dimensions (i.e., surgency, negative affectivity, and effortful control) with I) light PA (LPA), moderate PA (MPA), vigorous PA (VPA), and SED and II) meeting the PA recommendation in Finnish children aged 3–6 years.

Methods

Study design and participants

The present study utilizes cross-sectional data from the Increased Health and Wellbeing in Preschools study (DAGIS), which aimed to diminish socioeconomic differences in preschool children’s energy balance-related behaviors [15]. The study was conducted in early childhood education and care (ECEC) centers in southern and western Finland in 2015–2016. The eligibility criteria for the study were: I) having at least one group consisting of 3–6-year-old children, II) providing early education only during the daytime, III) being Finnish or Swedish speaking (official languages of Finland), and IV) being municipality driven. In total, 864 children (25% of the invited children, boys 52%) and their families from 66 ECEC centers (43% of the invited ECEC centers) in 8 municipalities agreed to participate in the study. All children with complete data on temperament and accelerometer data (including ≥3 weekdays and ≥ 1 weekend day) were included in the current study (N = 697, 81% of the total sample). Parents/caregivers gave their written informed consent. The study was approved by the University of Helsinki Ethical Review Board in the Humanities and Social and Behavioral Sciences in February 2015 (#6/2015).

Data collection

Children’s temperament was evaluated using the Very Short Form of the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire that was developed for children aged 3–8 years [16]. One parent in each family indicated their opinion on the 36 items included in the questionnaire, using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (= extremely false) to 7 (= extremely true). The three broad temperament dimensions established by the instrument developers were constructed from the questionnaire (12 items in each): surgency, negative affectivity, and effortful control. Surgency refers to tendencies to exhibit impulsivity, enjoy situations with high stimulus intensity, and not show discomfort in social situations. Negative affectivity refers to tendencies to have a lowered mood, being angry and fearful, and having difficulties soothing. Effortful control refers to tendencies to have the capacity to suppress inappropriate responses, better self-regulation, and ability to maintain focus on task-related activities [16]. Examples of the questions in each dimension have been previously published [17]. The questionnaire has been shown to demonstrate acceptable internal consistency and criterion validity in children [16]. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha values for surgency, negative affectivity, and effortful control were 0.80, 0.76 and 0.74, respectively.

PA and SED were measured using a hip-worn ActiGraph wGT3X-BT accelerometer (Pensacola, FL, USA) for 7 days, 24 h per day. Parents reported the non-wearing hours of the accelerometers (e.g., during water-based activities) in a diary. A 15-s epoch length was used, and periods of ≥10 min of consecutive zeros were regarded as non-wearing time [18]. A valid day was defined as ≥600 min of awake wearing time. The time spent in different PA intensities and SED were calculated using Butte’s cut-points [19], and they were further defined as LPA, MPA, VPA, and SED. The PA recommendation was defined as having at least 180 min of daily PA, of which at least 60 min/day was MVPA [3].

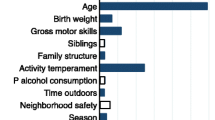

To further test the linkages of temperament with PA and SED, potential confounders (children’s physical characteristics, parental educational level, and the season of the year) were adjusted for in the analyses. Children’s age and sex were reported by the parents. Weight and height were measured by trained researchers, and thereafter, body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight (kg) / height2 (m). The BMI standard deviation score (BMI-SDS) was computed by the national references [20]. The threshold for being overweight was defined using the age- and sex-specific BMI cutoffs of the International Obesity Task Force criteria [21]. The highest educational level in the household was used as an indicator of socioeconomic status (SES), since SES has been previously associated with PA in children [22]. The educational level of both parents was inquired by a questionnaire, and the higher educational level was further categorized as low educational level (i.e., comprehensive, vocation, or high school), middle educational level (i.e., bachelor’s degree or college), or high educational level (i.e., master’s degree or licentiate/doctor). Seasonal variabilities in weather and daylight may also influence children’s PA and SED behaviors [23]. Since families participated in the study during different seasons, we divided the research season into three categories: fall (September–October), winter (November–December), and spring (January–April).

Statistical methods

Descriptive information is given as arithmetic means and standard deviations (SD) or frequencies and percentages (%). Using linear regression analysis, we examined associations of each temperament dimension with SED, LPA, MPA, and VPA adjusting for: I) accelerometer awake wearing time, II) child’s age and sex, research season, SES, and awake wearing time, and III) child’s age and sex, research season, SES, awake wearing time, and the two other temperament dimensions. Using logistic regression analysis, we examined associations between temperament and meeting the PA recommendation adjusted similar to the 3 models mentioned above. Sex comparisons among average values were made by using an independent t-test for continuous variables and a chi-square test for categorized variables. Statistical tests were conducted using the two-sided 5% level of significance and performed using SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Although we are presenting cross-sectional analyses, we considered that a sample size of 694 provides 80% power (two-tailed and α = 0.05) to detect an unstandardized regression coefficient of 0.11.

Results

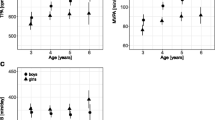

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 697 participating children subdivided by sex. Boys were taller and heavier, and they had higher scores in surgency and lower scores in effortful control than girls. Boys also spent less time in SED and more time in MPA and VPA than girls.

Associations of temperament with SED and PA

Table 2 presents all three models. A higher score in surgency was associated with lower SED (B = − 11.5, p < 0.001) and greater LPA (B = 3.8, p = 0.004), MPA (B = 4.9, p < 0.001), and VPA (B = 2.9, p < 0.001) after adjusting for child’s age and sex, SES, research season, and awake wearing time of the accelerometer (i.e., model 2). After including the other temperament dimensions in the model (i.e., model 3), the associations remained significant (SED: B = − 10.5, p < 0.001; LPA: B = 3.5, p = 0.014; MPA: B = 4.5, p < 0.001; VPA: B = 2.7, p < 0.001, respectively).

A higher score in effortful control was associated with greater SED (B = 8.7, p < 0.001) and lower MPA (B = − 3.6, p < 0.001) and VPA (B = − 2.5, p < 0.001) after adjusting for child’s age and sex, SES, research season, and awake wearing time of the accelerometer (i.e., model 2). After including the other temperament dimensions in the model (i.e., model 3), the associations remained significant (SED: B = 5.3, p = 0.023; MPA: B = − 2.2, p = 0.007; VPA: B = − 1.6, p = 0.007). No significant relationships between negative affectivity and SED or any of the PA intensities were discovered.

Associations between temperament and meeting the PA recommendation

A higher surgency was associated with higher odds of meeting the PA recommendation after adjusting for child’s age and sex, SES, research season, and awake wearing time of the accelerometer (OR = 1.56, p < 0.001) (Table 3). The association remained significant after adding the other temperament dimensions in the model (OR = 1.48, p = 0.004). A higher effortful control was associated with lower odds of meeting the PA recommendation after adjusting for child’s age and sex, SES, research season, and awake wearing time of the accelerometer (OR = 0.61, p = 0.004), and the association remained significant after adjusting for the other temperament dimensions (OR = 0.67, p = 0.026). No significant relationship between negative affectivity and meeting the PA recommendation was discovered.

Discussion

Our main findings are that a higher score in surgency was associated with greater PA and lower SED, whereas a higher score in effortful control was associated with lower PA and greater SED in a sample of Finnish preschool-aged children. In addition, a higher score in surgency was associated with higher odds of meeting the PA recommendation, while a higher score in effortful control was associated with lower odds of meeting the recommendation. The results support our hypothesis that temperament, as an intraindividual factor, may have an essential role in contributing to the development of PA and SED behavior at a young age.

We found that a higher score in surgency was associated with lower SED; greater LPA, MPA, and VPA; and higher odds of meeting the PA recommendation. Although the associations slightly weakened, they remained significant after taking the two other temperament dimensions (i.e., negative affectivity and effortful control) into account. This result indicates that after adjusting for the afore-mentioned characteristics in young children, a higher score in surgency is associated with all PA intensities (i.e., LPA, MPA, and VPA) and with lower SED. Our findings are in line with the study by Schmutz et al. [13], who found that temperamental activity in preschool children, based on the parent-reported Emotionality, Activity, and Sociability Temperament Survey, was associated with lower SED and greater PA in longitudinal design. These results, together with ours, highlight that although the temperament dimensions have been defined in a different way, temperament characteristics such as high activity level, high-intensity pleasure seeking, and low shyness and impulsivity seem to be associated with greater PA and lower SED. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, the association between temperament and meeting the PA recommendation has not been previously studied in preschool children. Thus, our finding that preschool children with a higher score in surgency were more likely to meet the PA recommendation extends the current literature. In addition, we found that surgency was associated with greater LPA, which has not been previously reported. These results indicate that children who have characteristics reflecting higher levels of surgency may more likely gain health benefits that are linked with regular PA [1, 3].

A previous longitudinal study in Finland [12] found that high childhood temperamental activity was associated with decreased levels of self-reported PA in adulthood in men but not in women. Similarly, it is possible that childhood characteristics related to surgency may not straightforwardly contribute to favorable PA behavior up to adult age. In light of this understanding, the potential mechanisms between the examined biologically based characteristics and behavioral outcomes in later life is important. Yet, the knowledge on the potential mediators within the association between temperament and PA during the lifespan is scarce. It is possible that temperament characteristics reflecting surgency may also contribute to the development of a physically inactive lifestyle in later life, as the attractive behaviors become more versatile with age. Therefore, young children who have characteristics reflecting higher levels of surgency and are more physically active may need guidance on how to find high-intensity pleasure from PA to gain health benefits in the long term.

A higher effortful control was significantly related to greater SED, lower MPA and VPA, and lower odds of meeting the PA recommendation. It is possible that the children with higher scores in effortful control feel more need to observe the environment and to control their own behavior, leading to more time spent in SED and less in high-intensity PA, such as MPA or VPA. Moreover, it has been suggested that children with higher levels of effortful control may be more able to follow instructions and prohibitions from adults, which may also affect their behavior by reducing their PA [24]. Thus, it is essential to identify these children to be able to support each child’s natural way of being physically active. This may be, for instance, mindfully restricting the amount of stimulus in an environment in order to support the child’s focus on play and movement. Nevertheless, future studies using a longitudinal design to elucidate this association are still needed to be better able to support children’s PA.

No statistically significant associations of negative affectivity with SED or any of the PA intensities were found, which is partly in line with the two previous studies [25, 26]. A cross-sectional study by Innella et al. [25] also reported that negative affectivity was not associated with parent-reported PA in 100 Hispanic preschool children. However, another cross-sectional study by Sharp et al. [26] found that higher negative affectivity was associated with less outdoor play in 3393 children aged 1–5 years. Because of the different study designs, further studies are needed to investigate the association between temperament and accelerometer-derived SED and PA, and to clarify the role of negative affectivity in PA in young children.

It has been suggested that temperament is a relatively stable construct (e.g. [27]), and each individual’s inherited behavioral styles interact dynamically with the environment across the life span. Therefore, it would be interesting to study whether and how children with different temperamental characteristics establish and maintain PA habits when environmental surroundings (e.g., social referents such as peers) change. Such changes are likely to occur when an individual proceeds through distinct developmental phases (e.g., a transition from adolescence to adulthood). It has been shown that as healthy people mature, they become more self-directed and cooperative [28], which may also associate with the formation of their PA behaviors in later life.

The findings of this study should also be discussed in relation to adults living close to the children and having impact on them. It would be useful that parents become aware of their child’s or children’s temperamental characteristics in order to be able to support their PA in everyday life. Furthermore, it is essential that ECEC centers’ personnel and health care professionals are aware of children’s different temperamental characteristics and their contribution to behavior. This knowledge may help in targeting effective actions to improve PA in children with different reactive tendencies and needs. For instance, in collaboration with other health care professionals (e.g., sports psychologists) pediatricians could design and recommend different types of physical activities for preschoolers. These activities could also vary in terms of their frequencies and intensities depending on the child’s temperamental characteristics. The current study focused on associations of temperament with PA and SED, but previous studies have shown that temperament is also associated with eating habits and screen time in preschoolers [17, 29]. Thus, temperament seems to play an important role in the formation of health behaviors during childhood and should therefore be acknowledged by families and child care professionals in supporting children’s development. The strength of the present study is a relatively large sample size. Moreover, we used accelerometer-derived PA instead of a parent-reported questionnaire to better be able to capture children’s intermittent patterns of movement [18] and the assessment of PA over the entire day. The Very Short Form of the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire was used to evaluate children’s temperament and it has been reported to demonstrate acceptable internal consistency and criterion especially in children aged 3–8 years [16].

The study also has some limitations that need to be considered. Firstly, the cross-sectional study design limits the conclusion about causality between the observed associations. Secondly, the questionnaire used to assess children’s temperament included only three dimensions. Therefore, our results should be confirmed using questionnaires that divides temperament into multiple dimensions to investigate the relationships with PA and SED more deeply. Furthermore, in our study the temperament questionnaire was filled in by only one parent which may lead to misreporting. It has been previously noted that there is non-invariance between mothers’ and fathers’ ratings considering their child’s temperament characteristics [30]. Finally, because of the relatively low participation rate (25%), the sample may be somewhat selected limiting the generalizability of the results into the whole Finnish population.

The statistically significant associations presented in this study raise a need to address their clinical relevance. The magnitudes of the detected associations (i.e., adjusted coefficients) indicate that the findings may be relevant from a clinical point of view. For instance, a Swedish research group has reported that 5 min/day increase in MVPA was longitudinally associated with a healthier body composition and better physical fitness in preschool-aged children [31]. Thus, the results of the current study indicate that the observed associations may be strong enough to have public health importance, and therefore, should be noted when planning future intervention studies.

In conclusion, higher surgency was associated with greater PA, lower SED, and higher odds of meeting the PA recommendation in a sample of Finnish preschool children. Furthermore, higher effortful control was associated with lower PA, greater SED, and lower odds of meeting the PA recommendation. These observational results suggest that one-size-may-not-fit-all and children’s temperament should be taken into account in promoting PA in young children. Thus, motivating children in PA with respect to their temperament characteristics may be essential in health-enhancing interventions. Different temperamental characteristics should be considered when planning interventions to increase PA or decrease SED among young children, or when encouraging children to be physically active. Special attention should be paid to children with self-regulative tendencies.

Availability of data and materials

Researchers interested in the data and materials from this study may contact principal investigator Eva Roos, eva.roos@folkhalsan.fi.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BMI-SDS:

-

Body mass index standard deviation score

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ECEC:

-

Early childhood education and care center

- LPA:

-

Light-intensity physical activity

- MPA :

-

Moderate-intensity physical activity

- MVPA:

-

Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- VPA:

-

Vigorous-intensity physical activity

References

Carson V, Lee E, Hewitt L, Jennings C, Hunter S, Kuzik N, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between physical activity and health indicators in the early years (0-4 years). BMC Public Health. 2017;17(Suppl 5):854–63.

World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on physical activity, sedentary behavior and sleep for children under 5 years of age. 2019; https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/311664. Accessed 3 Aug 2020.

De Craemer M, McGregor D, Androutsos O, Manios Y, Cardon G. Compliance with 24-h movement behaviour guidelines among Belgian pre-school children: the ToyBox-study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(10):2171.

Chaput J, Colley RC, Aubert S, Carson V, Janssen I, Roberts KC, et al. Proportion of preschool-aged children meeting the Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines and associations with adiposity: results from the Canadian Health Measures Survey. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(Suppl 5):829–154.

Berenson GS. Childhood risk factors predict adult risk associated with subclinical cardiovascular disease: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90(10):L3–7.

Janz KF, Burns TL, Levy SM. Tracking of activity and sedentary behaviors in childhood: the Iowa Bone Development Study. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(3):171.

Simell O, Niinikoski H, Rönnemaa T, Raitakari OT, Lagström H, Laurinen M, et al. Cohort profile: the STRIP study, an infancy-onset dietary and life-style intervention trial. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(3):650–5.

Shiner RL, Buss KA, McClowry SG, Putnam SP, Saudino KJ, Zentner M. What is temperament now? Assessing progress in temperament research on the twenty-fifth anniversary of goldsmith et al. Child Dev Perspect. 2012;6(4):436–44.

Buss AH, Plomin R. A temperament theory of personality development. Oxford: Wiley; 1975.

Rothbart MK. Becoming who we are. New York: [U.A.]: Guilford Press; 2011.

Yang X, Kaseva K, Keltikangas-Järvinen L, Pulkki-Råback L, Hirvensalo M, Jokela M, et al. Does childhood temperamental activity predict physical activity and sedentary behavior over a 30-year period? Evidence from the Young Finns Study. Int J Behav Med. 2017;24(2):171–9.

Schmutz EA, Haile SR, Leeger-Aschmann CS, Kakebeeke TH, Zysset AE, Messerli-Bürgy N, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior in preschoolers: a longitudinal assessment of trajectories and determinants. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15(1):35.

Buss A, Plomin R. Temperament: early developing personality traits. Hills-dale: Erlbaum; 1984.

Lehto E, Ray C, Vepsäläinen H, Korkalo L, Lehto R, Kaukonen R, et al. Increased health and wellbeing in preschools (DAGIS) study—differences in children’s energy balance-related behaviors (EBRBs) and in long-term stress by parental educational level. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(10):2313.

Putnam SP, Rothbart MK. Development of short and very short forms of the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. J Pers Assess. 2006;87(1):102–12.

Kaukonen R, Lehto E, Ray C, Vepsäläinen H, Nissinen K, Korkalo L, et al. A cross-sectional study of children's temperament, food consumption and the role of food-related parenting practices. Appetite. 2019;138:136–45.

Cliff DP, Reilly JJ, Okely AD. Methodological considerations in using accelerometers to assess habitual physical activity in children aged 0–5 years. J Sci Med Sport. 2008;12(5):557–67.

Butte NF, Wong WW, Lee JS, Adolph AL, Puyau MR, Zakeri IF. Prediction of energy expenditure and physical activity in preschoolers. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2014;46(6):1216–26.

Saari A, Sankilampi U, Hannila M, Kiviniemi V, Kesseli K, Dunkel L. New Finnish growth references for children and adolescents aged 0 to 20 years: length/height-for-age, weight-for-length/height, and body mass index-for-age. Ann Med. 2011;43(3):235–48.

Cole TJ, Lobstein T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr Obes. 2012;7(4):284–94.

Kantomaa MT, Tammelin TH, Näyhä S, Taanila AM. Adolescents’ physical activity in relation to family income and parents’ education. Prev Med. 2007;44(5):410–5.

Nilsen AKO, Anderssen SA, Ylvisaaker E, Johannessen K, Aadland E. Physical activity among Norwegian preschoolers varies by sex, age, and season. Scan J Med Sci. 2019;29(6):862–73.

Kochanska G, Aksan N. Children’s conscience and self-regulation. J Pers. 2006;74(6):1587–618.

Innella N, McNaughton D, Schoeny M, Tangney C, Breitenstein S, Reed M, et al. Child temperament, maternal feeding practices, and parenting styles and their influence on obesogenic behaviors in Hispanic preschool children. J Sch Nurs. 2019;35(4):287–98.

Sharp JR, Maguire JL, Carsley S, Abdullah K, Chen Y, Perrin EM, et al. Temperament is associated with outdoor free play in young children: a TARGet Kids! Study. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(4):445–51.

Lombard-Vance R. Developmental stability of temperament characteristics: a review. Stud Psychol J. 2011;1:1–9.

Josefsson K, Jokela M, Cloninger CR, Hintsanen M, Salo J, Hintsa T, et al. Maturity and change in personality: Developmental trends of temperament and character in adulthood. Dev Psych. 2013;25(3):713–27.

Leppänen MH, Sääksjärvi K, Vepsäläinen H, Ray C, Hiltunen P, Koivusilta L, et al. Association of screen time with long-term stress and temperament in preschoolers: results from the DAGIS study. Eur J Pediatr. 2020;179(11):1805.

Clark DA, Listro CJ, Lo SL, Durbin CE, Donnellan MB, Neppl TK. Measurement invariance and child temperament: an evaluation of sex and informant differences on the Child Behavior Questionnaire. Psychol Assess. 2016;28(12):1646–62.

Leppänen MH, Henriksson P, Delisle Nyström C, Henriksson H, Ortega FB, Pomeroy J, et al. Longitudinal physical activity, body composition, and physical fitness in preschoolers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49(10):2078–85.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participating families, the early childhood education and care centers, and the members of the DAGIS research group for their help regarding recruitment and data collection.

Funding

This research was funded by Folkhälsan Research Center, University of Helsinki, The Ministry of Education and Culture in Finland, The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, The Academy of Finland (Grants: 285439, 287288, 288038), The Juho Vainio Foundation, The Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation, The Finnish Cultural Foundation/South Ostrobothnia Regional Fund, The Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation, Medicinska Föreningen Liv och Hälsa, Finnish Foundation for Nutrition Research, and Finnish Food Research Foundation. KK was additionally granted by the Amer Cultural Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ER is the principal investigator for the DAGIS study and designed this research together with all coauthors. MHL was responsible for data analysis and drafted the manuscript, which was subsequently reviewed by KK, RP, KS, EM, EE, CR, ME, and NS. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the University of Helsinki Ethical Review Board in the Humanities and Social and Behavioral Sciences in February 2015 (#6/2015), and it was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Guardians gave their written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Leppänen, M.H., Kaseva, K., Pajulahti, R. et al. Temperament, physical activity and sedentary time in preschoolers – the DAGIS study. BMC Pediatr 21, 129 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02593-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02593-4