Abstract

Background

Considering that changes in the choroidal thickness are closely related to ocular growth, we studied the choroidal thickness (CT) and the blood flow features in children with unilateral myopic anisometropia (UMA) as well as investigating the relationship between choroidal changes and myopia.

Methods

Subjective refractive, axial length (AL), and biometric parameters were measured in 98 UMA children (age: 8–15 years). CT and choroidal blood-flow features, including the choroidal vessel volume (CVV), choroidal vascularity index (CVI), and choriocapillaris perfusion area (CCPA), were measured through swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography. The macular region was categorized into four concentric circles of diameters 0–1 mm (central fovea), 1–3 mm (parafovea), 3–6 mm (perifovea), and 6–9 mm (extended), and further categorized into superior (S), inferior (I), temporal (T), and nasal (N) quadrants.

Results

The aforementioned four regions of myopic eyes displayed significantly lower CT, CVV, and CVI than those of non-myopic eyes. CCPA changes differed across different regions of both the eyes (parts of N and T quadrants). There was an inverse association between CT and the interocular AL difference (central and other regions S, T quadrant). No correlation was noted between CVV and CVI with interocular AL difference. CT and CVV were positively correlated in the 0–6-mm macular region of myopic eyes (Spearman correlation coefficient = 0.763, P < 0.001).

Conclusions

In UMA children, CCT and blood flow may be related to myopia progression. A robust correlation between CT and CVV in the 0–6-mm macular region and reduced CT and diminished blood flow indicated an association with myopia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Myopia, the most common eye disease globally, can lead to irreversible vision loss and blindness [1]. The prevalence of myopia in Asia has surged to 90% among adolescents and young adults [2, 3]. Myopia, particularly high myopia, is associated with excessive axial elongation, which increases the risk of various ocular complications [4,5,6], including retinal degeneration, fissures, choroidal neovascularization, and posterior staphyloma. Therefore, an improved understanding of factors contributing to myopia development and axial elongation is crucial for myopia control.

While the specific mechanisms underlying myopia development and progression remain unclear, mounting evidence suggests choroidal involvement in myopia development [7, 8]. The choroid comprises highly vascularized tissues and can be histologically divided into five layers: starting from the innermost (retina), that is, the Bruch’s membrane, choriocapillaris, small and medium vessel layer (Sattler’s layer), large vessel layer (Haller’s layer), and suprachoroidal space. The choroid primarily supplies nourishment and oxygen for the outer retina and sclera [9]. However, the choroid has two additional functions: regulating the retinal position by altering the choroidal thickness (CT) and releasing growth factors involved in vascularization, scleral remodeling, and ocular growth regulation [10,11,12,13,14]. When patients are defocused due to myopia or hyperopia, CT undergoes bidirectional changes, which is referred to as “choroidal regulation.” [9, 15, 16] Some studies have demonstrated choroidal thinning and reduced blood perfusion in the early developmental stages of myopia, which lead to insufficient oxygen and nutrient supply to the peripheral sclera, eventually triggering axial elongation and myopia [17, 18]. Thus, additional studies are required for exploring overall choroidal changes in children and their relationship with myopia to better understand the role played by the choroid in myopia pathogenesis.

Since its discovery in 1995 [19], swept-source optical coherence tomography (SS-OCT) has evolved into a valuable tool for retinal imaging. When compared with the conventional spectral-domain (SD) OCT, SS-OCT employs longer wavelengths that improve the depth resolution of retinal imaging. With SS-OCT, the vitreous, retina, and choroid can be simultaneously imaged, and microvascular blood flow imaging can be performed through optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) [20, 21]. OCTA was recently applied in clinical studies for assessing choroidal vasculature and choriocapillaris perfusion in adults and children with myopic anisometropia [22,23,24,25], yielding diverse results about the association of choroidal microvascular perfusion and blood flow with refractive error or axial elongation. This inconsistency is attributable to choroidal structure differences across different age groups. In addition, without emmetropic eyes as controls, assessing their associations with myopia would be challenging. Unilateral myopic anisometropia (UMA) is a specific condition of myopic anisometropia in which an unequivocally myopic eye is paired with a “plano” (SERE = ± 0.25 D) companion eye [26]. Children with UMA are a unique study population. Differences in CT and blood flow between myopic and non-myopic eyes must be observed in the same individual, and their associations with the interocular axial length (AL) difference must be evaluated. The results obtained can help analyze and explore the relationship between myopia development and choroidal changes after controlling for confounding factors such as age, gender, genetics, and environment. This approach can yield scientifically robust results concerning the correlation between myopia and choroidal changes.

In this study, accordingly, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of CT, choroidal vessel volume (CVV), choroidal vascularity index (CVI), and choriocapillaris perfusion area (CCPA) in both the eyes of UMA children by using SS-OCTA to evaluate the associations between CT and blood flow with myopia.

Methods

Participants

This cross-sectional study included 8- to 15-year-old children who were treated at the Optometry Department of Beijing Aier-Intech Eye Hospital from January to June 2023 and diagnosed with UMA. Demographic information of the children was collected from their electronic medical records. This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Aier-Intech Eye Hospital (No. BJAIER2024IRB41). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects and their guardians.

Ocular examinations, including subjective noncycloplegic spherical equivalent refractions (SERs), slit lamp examination, measurements of best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and AL (IOLMaster 700, Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany), and SS-OCT, were performed. All subjects’ SERs ranged from −4.50 D to −0.25 D in the myopic eye and between −0.5 D and +1.25 D in the fellow eye, with a BCVA of 20/20 or better in the myopic eye and the contralateral eye was emmetropic. None of the participants had serious eye diseases, such as congenital cataracts, glaucoma, and strabismus, or active inflammatory ocular surface diseases. The participants with a history of ocular or systemic diseases that affected the choroid, ocular surgeries, spectacles/contact lens wear, or low-concentration atropine were excluded from the study.

All examinations were conducted from 09:00 AM to 03:00 PM to control for diurnal variations in the choroidal structure [27]. In total, three consecutive scans were obtained, and the clearest image was used for further analyses.

OCTA image acquisition and analysis

Choroidal blood flow and images were obtained through SS-OCTA (VG200S, SVision Imaging, Henan, China). The SS-OCT/OCTA system has a scanning source laser with a central wavelength of approximately 1050 nm and a scanning rate of 200,000 A-scans per second. In addition, the system has an integrated confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope for eye motion tracking to eliminate motion artifacts. The system has an axial resolution of 5 μm, a lateral resolution of 13 μm, and a scan depth of 3 mm.

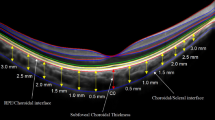

In SS-OCT images, the choroid is the layer from the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)–Bruch’s membrane complex to the choroid–scleral junction (Fig. 1A). Choroidal images and blood flow data were obtained with the central fovea as the center, capturing a 6 × 6-mm area with 512 B-scans (horizontal lines) in the blood flow mode. Each B-scan comprises 512 A-scans, while B-scanning was repeated four times to achieve an average value. The OCTA fundus images and choroidal blood flow data were automatically generated using the SVision SS-OCTA algorithm. The choroidal vascular parameters are computed using the built-in software of the SS-OCT/OCT-A instrument (Vangogh, Intalight). The luminal and stromal areas were determined through a segmentation algorithm designed for CVI and CVV. For the calculation of the choriocapillaris perfusion area, the blood-flow signal intensity was employed to differentiate between pixels indicating the blood flow and those representing non-blood flow by using an empirical threshold. Subsequently, the total number of blood flow pixels was counted and converted into the final flow area, which accounted for the imaging dimensions. Following the same principle, the number of blood flow voxels was obtained from volumetric data and converted into a volume measurement (mm³) representing CVV, taking into account the axial resolution (voxel size). VG does not provide CCPA, but it is easy to obtain CVI = CCPA/(total area).

A Area of the choroid in OCT angiography. Machine-automated identification of the upper and lower boundaries of the choroid (blue lines) and the region of choroidal vessels (orange-red area). B Cross-sectional illustration of choriocapillaris perfusion analysis. The boundaries of the choriocapillaris layer (blue)

The choroidal thickness and blood flow parameters were extracted and measured with reference to a customized algorithm using MATLAB R2017a, with the post-correction of AL. In short, we adjusted the ocular magnification by using Bennett’s formula. The relationship between the measured OCTA diameter (Dm) and the actual diameter (Da) was expressed as Da = p × q × Dm, in which p is the magnification factor and q is calculated as 0.01306 × (AL −1.82) [24].

We evaluated en face choriocapillaris blood flow, which is defined as the layer starting at the basal boundary of the RPE–Bruch’s membrane complex and ending approximately 20 μm below it [28, 29] (Fig. 1B). The projection artifacts of retinal vessels in each quadrant were eliminated using machine algorithms.

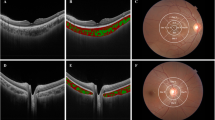

Using the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) grid, the macular region was divided into three concentric circles with diameters of 1 mm (central fovea), 3 mm (parafovea), and 6 mm (perifovea) (Fig. 2). We here extended this grid to a 9-mm (extended) range. The parafoveal, perifoveal, and extended regions were further divided into superior (S), inferior (I), temporal (T), and nasal (N) quadrants (Fig. 2).

Distribution of CT and choroidal vessels. Extended macular ETDRS grid (using the right eye as an example). The measurement of choroidal thickness and choroidal vascularity and choriocapillaris blood perfusion. The macular region was divided into four concentric circles with diameters of 1 mm (central fovea), 3 mm (parafovea), 6 mm (perifovea), and 9 mm (extended). The parafoveal, perifoveal, and extended regions were further divided into superior (S), inferior (I), temporal (T), and nasal (N) quadrants. C: central fovea

Statistical analyses

The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov—Smirnov test. Normally distributed continuous variables were described using the mean ± standard deviation, while non-normally distributed continuous variables were described using the median (25th percentile, 75th percentile). Categorical variables were presented as the sample size (proportion). Trend tests were conducted based on group medians to determine the trend of changes in the CT and blood flow from the central to the peripheral regions. Paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were employed to analyze the interocular differences. The Spearman’s correlation test was performed to explore the associations of CT, CVV, CVI, and CCPA with interocular AL differences in myopic eyes. In addition, the relationship between CT and blood flow in the 0–6-mm macular area was investigated. Variables with missing proportions >20% were excluded, and no imputation was performed for the included variables (Supplementary Table 1).

Results

Demographics

A total of 98 UMA children with an average age of 10.29 ± 2.31 years were included. Among them, 46 (46.9%) were male, and 33 (33.7%) children had myopia in their left eyes. The average AL of the myopic eye was 24.15 ± 0.74 mm, with the left and right myopic eyes having ALs of 24.31 ± 0.73 mm and 24.08 ± 0.74 mm, respectively. The keratometry readings for the myopic eyes were 42.91 ± 1.24 for flat K and 44.10 ± 1.28 for steep K. In contrast, the non-myopic eyes had keratometry readings of 42.84 ± 1.21 for flat K and 44.10 ± 1.30 for steep K (Table 1).

Distribution of CT in UMA Children

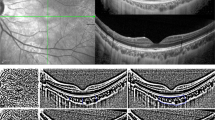

In the UMA Children, CT gradually decreased from the central to peripheral regions in both eyes (both P < 0.001, Fig. 3A). Differences in CT across the 13 sub-regions were observed. Among these sub-regions, CT was thickest in the T quadrant and thinnest in the Extended N quadrant. Across all sub-regions, CT was significantly lower in the myopic eyes than in the non-myopic eyes (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Choroidal blood flow

CVV distribution in UMA Children

CVV increased gradually from the central to peripheral regions in both eyes (both P < 0.001, Fig. 3B). CVV differed significantly across 13 subregions. The extended S and T quadrants had the largest CVV, with a volume of 0.95 (0.87, 1.03) and 0.96 (0.89, 1.04), respectively, whereas the smallest CVV was noted for the central region (0.09 [0.08, 0.10]). Across all subregions, CVV was significantly lower in the myopic eyes than in the non-myopic eyes (P < 0.05, Table 3).

CVI distribution in UMA Children

In both eyes, CVI decreased gradually from the central to the peripheral regions (both P < 0.001, Fig. 3C). Significant differences in CVI were observed across the 13 subregions. CVI was the highest in the central and parafoveal regions and the lowest in the extended N quadrant (0.33 [0.28, 0.37]). Across all subregions, CVI was significantly lower in the myopic eyes than in the non-myopic eyes (P < 0.001, Table 4).

CCPA in UMA Children

In both eyes, CCPA steadily increased from the central to the peripheral regions (both P < 0.001, Fig. 3D). CCPA changes differently in different regions of both eyes (parts of N and T quadrants) The extended T quadrant and the central region displayed the largest and smallest CCPA (6.67 [6.47, 6.95] vs. 0.58 [0.58, 0.61]). In the parafoveal, perifoveal, and extended N quadrants, CCPA was significantly smaller in the myopic eyes than in the non-myopic eyes (P < 0.05). CCPA exhibited no significant interocular differences in other subregions (P > 0.05, Table 5).

Associations of CT and choroidal flood flow in myopic eyes of UMA Children with an interocular AL difference

CT and the interocular AL difference were negatively correlated in the central region, S quadrants of parafovea, perifoveal, and extended regions (correlation coefficients: −0.220, −0.201, −0.235, and −0.279, respectively). Only in the extended I quadrant, CCPA was positively correlated with the interocular AL difference (correlation coefficients: 0.230. No correlation was observed between CVV and CVI with interocular AL difference (Table 6).

Correlation between CT and choroidal blood flow in the 0–6-mm macular region in myopic eyes of UMA Children

In the myopic eyes, CT and CVV in the 0–6-mm macular region were significantly positively correlated (Spearman’s correlation coefficient: 0.763, P < 0.001). However, no significant correlations were noted between CT and CVI or CCPA (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Clinical studies employing OCT have recently revealed that, as myopia progresses, the choroid tends to become thinner. Changes in the choroidal thickness are closely related to ocular growth [30,31,32]. Because of the highly vascular nature of the choroid and its potential role in scleral hypoxia, some studies have suggested that reduced choroidal blood flow may be linked to myopia development [17, 33]. Here, we employed SS-OCTA to dynamically assess changes in the choroidal blood flow perfusion on the basis of segmental scans centered around the macular region. SS-OCTA employs horizontal and vertical scans for three-dimensional vascular imaging, which offers detailed and accurate choroidal visualizations [34]. The images of dynamic blood flow changes across different sub-regions facilitate the elucidation of myopia development-associated choroidal vascular alterations. SS-OCTA has been widely adopted by studies involving adults with high or pathological myopia [35]. However, the relationship between changes in the choroidal blood flow and myopia development needs in-depth investigation. We here comprehensively analyzed the distribution of CT and choroidal blood flow in UMA children, as well as their associations with the interocular AL difference. This study offers valuable evidence to comprehensively understand the relationship between choroid and myopia.

In UMA children, CT and CVI slowly decreased from the central to the peripheral regions (I-S-N-T), whereas CVV and CCPA increased from the central to the peripheral regions (I-S-N-T) (all P < 0.001). This observation implies that the distribution of CT and choroidal blood flow exhibited a consistent pattern in both myopic and non-myopic eyes. Choroidal blood flow in adults with anisometropia exhibited that choroidal thinning and reduced choroidal blood flow were correlated [22], which is consistent with our findings. This finding also implies that choroidal changes between adults and children were consistent. Furthermore, we found that CT was thinner and CCV, CVI was lower in the myopic eyes than in the non-myopic eyes; however, only in parts of extended N and T quadrants, CCPA display significant differences, indicating that CCPA may not decrease during the early stage of myopia, which is consistent with the results of Liu et al. [24]. Longitudinal studies have recently confirmed the correlation between myopia and CT [31, 36], suggesting that choroidal thinning is related to accelerated ocular growth and myopia development in children and adolescents. Our findings are consistent with these results. Rapid changes in CT may be related to vascular regulation rather than matrix components [9, 33, 37]. Therefore, choroidal vasculature remains a captivating topic in ocular research. However, the exact physiological mechanisms underlying the observed CT changes require further clarification.

In UMA children, CT was negatively correlated with the interocular AL difference in the central foveal and other regions S, T quadrants. No correlation was observed between CVV and CVI with interocular AL. In addition, only in the extended I quadrant, CCPA was positively correlated with the interocular AL difference. Furthermore, a significant positive correlation was observed between CT and CVV in the 0–6-mm macular region of the myopic eyes, whereas no significant correlations were noted between CT and CVI or CT and CCPA. These findings suggest that, in the follow-up assessments of refractive changes in adolescents and children, focusing on changes in CT in the central and other regions S, T quadrants, which may be valuable for assessing and predicting the myopia development trend. Furthermore, CVI values within the central 10 mm of the retina were consistent, whereas CT gradually decreased with eccentricity [38]. CVI has been investigated in both healthy populations and patients with ocular conditions [39,40,41,42]. However, only a few studies have explored the relationship between choroid and myopia, yielding vague and inconsistent findings [43,44,45]. Zhang et al. [33] recently proposed that reduced choroidal blood perfusion contributes to myopia development [33]. According to some studies, in highly myopic anisometropes, choroidal blood flow perfusion may be lower in eyes with a higher refractive error [22]. Nonetheless, our study identified no correlation among CCV, CVI, and the interocular AL difference, which may be attributable to the relatively low refractive errors in UMA children, where blood flow was not significantly reduced.

Because of the potential influence of medication on measurements, such as CT and AL [46], we opted not to induce cycloplegia and rather employed subjective noncycloplegic SERs. All UMA children in this study had only low myopia, which eliminated the influence of pathological changes such as retinal atrophy on the choroidal structure and blood flow. While studies investigating the relationship between anisometropia and the choroid in adults and children have described interocular differences within the same individual [22, 24], they lacked comparative results with emmetropic eyes as a reference. In contrast, we compared the interocular AL difference between the myopic and non-myopic eyes of UMA children with CT and choroidal blood flow features. These results offer a scientific and intuitive reflection of the relationship between myopia and changes in CT and choroidal blood flow. Furthermore, considering that CT responds rapidly and predictably to various visual stimuli, such as hyperopic or myopic defocus and accommodation [16, 47], our study findings can be useful for understanding the trend of myopia development, thereby facilitating effective interventions during the early myopia stages.

This study has several limitations. First, this is a cross-sectional study, and longitudinal evidence is required to evaluate whether changes in CT and choroidal blood flow have predictive implications for myopia progression. In addition, our study sample size was relatively small. Considering that UMA children were our study participants, we could not control for confounding factors as they had only low myopia. Hence, our findings may not be sufficiently generalizable among participants with varying refractive errors.

This finding is expected to facilitate ascertaining the role of biometric measurements in identifying myopic children who require urgent intervention. Furthermore, establishing the causal relationship between myopia-associated choroidal vascular and thickness changes and myopia development warrants further investigation in animal models and longitudinal studies.

Conclusions

In UMA children, changes in CT and choroidal blood flow exhibited a consistent pattern in myopic and non-myopic eyes. CT was thinner and blood flow was lower in the myopic eyes than in the non-myopic eyes. A strong correlation was observed between CT and CCV in the 0–6-mm macular region. These findings suggest that both CT and blood flow of large-medium choroidal vessels were affected in children with myopia, indicating that reduced CT and diminished blood flow are associated with myopia.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Choroidal thickness

- UMA:

-

Unilateral myopic anisometropia

- AL:

-

Axial length

- CVV:

-

Choroidal vessel volume

- CVI:

-

Choroidal vascularity index

- CCPA:

-

Choriocapillaris perfusion area

- S:

-

Superior

- I:

-

Inferior

- T:

-

Temporal

- N:

-

Nasal

- SS-OCT:

-

Swept-source optical coherence tomography

- OCTA:

-

Optical coherence tomography angiography

References

Morgan I, Ohno-Matsui K, Saw S, Myopia. Lancet (London England). 2012;379:1739–48.

Li S, Wei S, Atchison D, Kang M, Liu L, Li H, et al. Annual incidences and progressions of myopia and high myopia in Chinese schoolchildren based on a 5-year cohort study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2022;63:8.

Zhou X, Pardue M, Iuvone P, Qu J. Dopamine signaling and myopia development: what are the key challenges. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2017;61:60–71.

Flitcroft D. The complex interactions of retinal, optical and environmental factors in myopia aetiology. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012;31:622–60.

Ruiz-Medrano J, Montero J, Flores-Moreno I, Arias L, García-Layana A, Ruiz-Moreno J. Myopic maculopathy: current status and proposal for a new classification and grading system (ATN). Prog Retin Eye Res. 2019;69:80–115.

Ohno-Matsui K, Jonas J. Posterior staphyloma in pathologic myopia. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2019;70:99–109.

Read S, Collins M, Vincent S, Alonso-Caneiro D. Choroidal thickness in myopic and nonmyopic children assessed with enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:7578–86.

Read S, Fuss J, Vincent S, Collins M, Alonso-Caneiro D. Choroidal changes in human myopia: insights from optical coherence tomography imaging. Clin Exp Optom. 2019;102:270–85.

Nickla DL, Wallman J. The multifunctional choroid. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010;29:144–68.

Simon P, Feldkaemper M, Bitzer M, Ohngemach S, Schaeffel F. Early transcriptional changes of retinal and choroidal TGFbeta-2, RALDH-2, and ZENK following imposed positive and negative defocus in chickens. Mol Vis. 2004;10:588–97.

Rada J, Shelton S, Norton T. The sclera and myopia. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:185–200.

Jobling A, Wan R, Gentle A, Bui B, McBrien N. Retinal and choroidal TGF-beta in the tree shrew model of myopia: isoform expression, activation and effects on function. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:458–66.

Mathis U, Ziemssen F, Schaeffel F. Effects of a human VEGF antibody (Bevacizumab) on deprivation myopia and choroidal thickness in the chicken. Exp Eye Res. 2014;127:161–9.

Stephen JV, Michael JC, Scott AR, Leo GC. Retinal and choroidal thickness in myopic anisometropia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54.

Zhu X, Park TW, Winawer J, Wallman J. In a matter of minutes, the eye can know which way to grow. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2238–41.

Chiang ST, Phillips JR, Backhouse S. Effect of retinal image defocus on the thickness of the human choroid. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2015;35:405–13.

Wu H, Chen W, Zhao F, Zhou Q, Reinach PS, Deng L, et al. Scleral hypoxia is a target for myopia control. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E7091–100.

Wu P, Tsai C, Gordon G, Jeong S, Itakura T, Patel N, et al. Chondrogenesis in scleral stem/progenitor cells and its association with form-deprived myopia in mice. Mol Vis. 2015;21:138–47.

Laíns I, Wang J, Cui Y, Katz R, Vingopoulos F, Staurenghi G, et al. Retinal applications of swept source optical coherence tomography (OCT) and optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA). Prog Retin Eye Res. 2021;84:100951.

Barteselli G, Bartsch DU, Weinreb RN, Camacho N, Nezgoda JT, Marvasti AH, Freeman WR. Real-time full-depth visualization of posterior ocular structures: comparison between full-depth imaging spectral domain optical coherence tomography and swept-source optical coherence tomography. Retina. 2016;36:1153–61.

Stanga PE, Tsamis E, Papayannis A, Stringa F, Cole T, Jalil A. Swept-source optical coherence tomography Angio™ (Topcon Corp, Japan): technology review. Dev Ophthalmol. 2016;56:13–7.

Wu H, Zhang G, Shen M, Xu R, Wang P, Guan Z, et al. Assessment of choroidal vascularity and choriocapillaris blood perfusion in anisomyopic adults by SS-OCT/OCTA. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021;62:8.

Xu A, Sun G, Duan C, Chen Z, Chen C. Quantitative assessment of three-dimensional choroidal vascularity and choriocapillaris flow signal voids in myopic patients using SS-OCTA. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11.

Liu X, Lin Z, Wang F, Peng X, He W, Chen D, et al. Choroidal thickness and choriocapillaris vascular density in myopic anisometropia. Eye Vis (Lond). 2021;8:48.

Andrew KCL, Suk-Tak C, Ben C, Henry C. The effect of axial length on ocular blood flow assessment in anisometropes. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2003;23.

Pointer J, Gilmartin B. Clinical characteristics of unilateral myopic anisometropia in a juvenile optometric practice population. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2004;24:458–63.

Lee SW, Yu SY, Seo KH, Kim ES, Kwak HW. Diurnal variation in choroidal thickness in relation to sex, axial length, and baseline choroidal thickness in healthy Korean subjects. Retina. 2014;34:385–93.

Zhang Q, Zheng F, Motulsky E, Gregori G, Chu Z, Chen C, et al. A novel strategy for quantifying choriocapillaris flow voids using swept-source OCT angiography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:203–11.

Chu Z, Zhang Q, Gregori G, Rosenfeld P, Wang R. Guidelines for imaging the choriocapillaris using OCT angiography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;222:92–101.

Jin P, Zou H, Zhu J, Xu X, Jin J, Chang T, et al. Choroidal and retinal thickness in children with different refractive status measured by swept-source optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;168:164–76.

Jin P, Zou H, Xu X, Chang T, Zhu J, Deng J, et al. Longitudinal changes in choroidal and retinal thicknesses in children with myopic shift. Retina. 2019;39:1091–9.

Xiong S, He X, Zhang B, Deng J, Wang J, Lv M, et al. Changes in choroidal thickness varied by age and refraction in children and adolescents: a 1-year longitudinal study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;213:46–56.

Zhang S, Zhang G, Zhou X, Xu R, Wang S, Guan Z, et al. Changes in choroidal thickness and choroidal blood perfusion in Guinea Pig Myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:3074–83.

Yang J, Wang E, Yuan M, Chen Y. Three-dimensional choroidal vascularity index in acute central serous chorioretinopathy using swept-source optical coherence tomography. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258:241–7.

Uzun S, Pehlivan E. Vascular density in retina and choriocapillaris as measured by optical coherence tomography angiography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;169:290.

Read S, Alonso-Caneiro D, Vincent S, Collins M. Longitudinal changes in choroidal thickness and eye growth in childhood. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:3103–12.

Fitzgerald ME, Wildsoet CF, Reiner A. Temporal relationship of choroidal blood flow and thickness changes during recovery from form deprivation myopia in chicks. Exp Eye Res. 2002;74:561–70.

Breher K, Terry L, Bower T, Wahl S. Choroidal biomarkers: a repeatability and topographical comparison of choroidal thickness and choroidal vascularity index in healthy eyes. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2020;9:8.

Tan K, Laude A, Yip V, Loo E, Wong E, Agrawal R. Choroidal vascularity index - a novel optical coherence tomography parameter for disease monitoring in diabetes mellitus? Acta Ophthalmol. 2016;94:e612–6.

Agrawal R, Chhablani J, Tan K, Shah S, Sarvaiya C, Banker A. Choroidal vascularity index in central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. 2016;36:1646–51.

Wei X, Ting D, Ng W, Khandelwal N, Agrawal R, Cheung C. Choroidal vascularity index: a novel optical coherence tomography based parameter in patients with exudative age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2017;37:1120–5.

Tan R, Agrawal R, Taduru S, Gupta A, Vupparaboina K, Chhablani J. Choroidal vascularity index in retinitis pigmentosa: an OCT study. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2018;49:191–7.

Li Z, Long W, Hu Y, Zhao W, Zhang W, Yang X. Features of the choroidal structures in myopic children based on image binarization of optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020;61:18.

Alshareef R, Khuthaila M, Goud A, Vupparaboina K, Jana S, Chhablani J. Subfoveal choroidal vascularity in myopia: evidence from spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2017;48:202–7.

Gupta P, Thakku S, Saw S, Tan M, Lim E, Tan M, et al. Characterization of choroidal morphologic and vascular features in young men with high myopia using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;177:27–33.

Bahar A, Pekel G. The effects of pharmacological accommodation and cycloplegia on axial length and choroidal thickness. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2021;84.

Woodman-Pieterse E, Read S, Collins M, Alonso-Caneiro D. Regional changes in choroidal thickness associated with accommodation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:6414–22.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design: LS, CFAcquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: LS, CZ, YWDrafting of the manuscript: LSStatistical analysis: LS, MX, YTAdministrative, technical, or material support: All authorsMethodology: WD, SL, CFSupervision: CFAll authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Aier-Intech Eye Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects and their guardians.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, L., Xue, M., Tang, Y. et al. Association of choroidal thickness and blood flow features with asymmetric axial lengths in children with unilateral myopic anisometropia. BMC Ophthalmol 24, 329 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-024-03616-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-024-03616-1