Abstract

Background

We evaluated the effect of vitrectomy with internal limiting membrane (ILM) peeling and gas tamponade for myopic foveoschisis (MF), and analysed prognosis with different gas tamponade.

Methods

Retrospective, non-randomized study. The records of patients with MF treated by vitrectomy, were reviewed. Patients were followed up postoperatively mean 16.74 months, to record changes of Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and central foveal thickness (CFT).

Results

Sixty-two eyes (59 patients) were analysed in total, with mean age of 55.29 ± 10.34 years, 49 females (83.1%). Foveoschisis completely resolved in all eyes at least 6 months post vitrectomy, except for two postoperative full-thickness macular holes (FTMH). Final BCVA improved significantly from 0.69 ± 0.39 to 0.44 ± 0.42 logMAR, and CFT from 502.47 ± 164.78 to 132.67 ± 52.26 μm. Patients were subdivided into three subgroups based on the different endotamponades used (C3F8, C2F6, and air). Baseline BCVA, baseline CFT and foveal detachment (FD) were not significantly different among the three groups. Eyes treated with air tamponade had better visual outcomes than eyes with C3F8 tamponade (P = 0.008). Baseline BCVA and FD were significant risk factors for postoperative BCVA (P < 0.001 and P = 0.013, respectively).

Conclusions

Vitrectomy with ILM peeling and gas tamponade results in good functional and anatomic outcomes in the treatment of most MF. Good vision and no-FD pre-surgery are related with good visual prognosis. Air tamponade can provide as good visual recovery as expansive gas, and reduce postoperative complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Myopic foveoschisis (MF) is considered one of the major causes of visual loss in highly myopic eyes [1, 2]. The estimated morbidity of MF is 8–34% in highly myopic eyes with posterior staphylomas [3, 4]. As recorded, the pathogenesis of MF is the combined effect of introversion traction and extroversion traction. Tangential vitreomacular traction is thought to be a crucial point [1, 2, 4]. Macular retinal detachment and macular hole are likely secondary complications occurring spontaneously following the development of MF, with disrupted ellipsoid zone (EZ).

The surgical options for MF include pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) and ILM peeling with or without gas tamponade, posterior scleral reinforcement alone or with vitrectomy. Moreover, the fovea-sparing ILM peeling technique has been reported to prevent iatrogenic macular holes and result in better anatomical and functional improvement than total ILM peeling [5,6,7]. Surgical approach, follow-up time, and the operator’s surgical skills can affect the surgical result. However, the necessity of gas tamponade or ILM peeling remains controversial [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22].

In this retrospective study, we evaluated BCVA and CFT changes of PPV with ILM peeling and gas tamponade for MF, and compared surgical outcomes and complications between eyes with different gas tamponade.

Methods

Patients

A retrospective review of 62 eyes of 59 patients who underwent PPV and ILM peeling with gas tamponade for MF was performed at Beijing Tongren Hospital, between March 2012 and August 2018. The inclusion criteria were axial length > 26.0 mm, the presence of neuroretina splitting detected on a spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT), progressive visual symptoms (visual loss or metamorphopsia) caused by MF, follow-up ≥6 months. The exclusion criteria were other pre-existing macular pathologies, a history of ocular surgery other than cataract surgery, low quality OCT scans with insufficient resolution. Diagnosis of MF is confirmed by neuroretina splitting into a thicker inner layer and a thinner outer layer in the macula and the presence of intraretinal columns, which can be definitely detected on a SD-OCT [4]. This research followed the Tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board. Data was collected from the hospital records and no patient involvement was required.

Examinations

BCVA was measured by the tumbling E charts and converted to logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (LogMAR) for statistical analysis. The detailed fundus was examined by indirect binocular ophthalmoscopy. Axial length was measured by IOL-Master. The macular architecture was evaluated using SD-OCT (Cirrus; Carl Zeiss, Dublin, CA). OCT images were accomplished using the ‘Macular Cube 512 × 128’ scan. The CFT was defined as the largest vertical distance measured manually between the retinal pigment epithelium and the inner retinal surface at the foveal area on horizontal OCT scan, with or without FD or lamellar hole. Other SD-OCT features were recorded: macular schisis, foveal detachment, epiretinal membranes, vitreomacular traction, lamellar holes. BCVA and OCT were recorded on all visits.

Surgical techniques

PPV was accomplished using a 23G vitrectomy system (Alcon Constellation Vision System). Combined phacoemulsification with simultaneous intraocular lens implantation was performed on phakic eyes in case of significant cataract. The posterior cortical vitreous was removed gently from the retina after core vitrectomy. After peeling the epiretinal membrane, the ILM was peeled in all cases and 0.2 ml of 0.25% ICG staining was performed, if necessary. The ILM was entirely peeled between the upper and lower vascular arcades. Before June 2017, gas tamponade (18% C2F6 or 14% C3F8) was injected after fluid-air exchange; since June 2017, sterile air was retained in the vitreous cavity. All patients were instructed to maintain prone postoperatively, long-acting gas for 1–2 weeks, air for 5–7 days.

Statistical methods

SPSS version 23.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was performed for statistical analysis. Qualitative data are presented as a value, and quantitative data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Independent-samples t-tests, Fisher’s Least Significant Difference test, Fisher’s exact test and chi-square test were used to compare the statistical significance of preoperative and postoperative outcome in BCVA, CFT, and various findings. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of 62 eyes of 59 patients (M:F = 10:49) are summarized in Table 1. All patients had undergone PPV and received ILM peeling with gas tamponade. Thirty eyes (48.4%) received phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation simultaneously with vitrectomy. At the mean 16.74-month follow-up visit, MF completely resolved in all eyes of our study except 2 complicated FTMH. Forty-three eyes (69.4%) showed improvement in BCVA, among which 31 eyes improved two lines or more (0.3 LogMAR units). Another 12 eyes (19.4%) remained stable vision and the other 7 eyes (11.3%) suffered a vision loss, which was caused by postoperative complications (FTMH, glaucoma, and complicated cataract). The mean BCVA improved significantly from 0.69 ± 0.39 logMAR (range 0.1 to 1.5 logMAR) to 0.44 ± 0.42 logMAR (range 0.0 to 2.3 logMAR), and mean CFT improved significantly from 499.20 ± 164.38 μm (n = 62) to 132.67 ± 52.26 μm (n = 60, eyes without FTMH). (both P < 0.001, paired t-test).

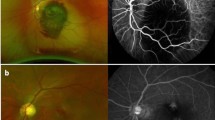

The preoperative and postoperative parameters between MF eyes with or without FD are shown in Table 2. We originally had 42 eyes in MF without FD group, but it was necessary to delete two mild splitting cases without FD in order to reduce the effect of selection bias on the comparison of FD group and non-FD group. The eyes with FD at baseline had a thicker mean CFT (593.85 ± 178.57 vs. 461.94 ± 133.37 μm; P = 0.003) and a worse mean BCVA (0.91 ± 0.34 vs. 0.61 ± 0.37 logMAR; P = 0.005) preoperatively, compared to those without FD at baseline. Both groups had significant improvement in CFT reduction and BCVA (Figs. 1 and 2). However, eyes with FD at baseline had a thinner mean CFT (113.60 ± 55.36 vs. 144.74 ± 48.44 μm; P = 0.034) and a worse mean BCVA (0.60 ± 0.36 vs. 0.36 ± 0.44 logMAR; P = 0.043) postoperatively.

Left eye of a 63-year-old woman with an axial length of 28.89 mm, undergoing PPV with ILM peeling and C3F8 tamponade combined cataract surgery. A Preoperative OCT image revealed severe foveoschisis, a lamellar hole, and an epiretinal membrane, without foveal detachment . The BCVA was 0.4. B Postoperative OCT at 1 month showed a partial resolution with decreased area of the foveoschisis . The BCVA improved to 0.6. C Postoperative OCT at 3 months showed foveal resolution and residual para-foveoschisis . The BCVA was maintained at 0.6. D Postoperative OCT at 1 year showed a complete foveal resolution and mild temporal para-foveoschisis. The BCVA improved to 0.7

Left eye of a 54-year-old aphakic woman with an axial length of 30.7 mm, undergoing PPV with ILM peeling and air tamponade. A Preoperative OCT image revealed severe foveoschisis with foveal detachment. The BCVA was 0.2. B Postoperative OCT at 1 month showed a partial resolution with decreased height and area of the foveoshisis. The BCVA was 0.2. C Postoperative OCT at 3 months showed residual foveoschisis with shallow foveal detachment. The BCVA improved to 0.3. D Postoperative OCT at 1 year showed a complete retinal reattachment and resolution of foveoschisis. The BCVA improved to 0.4

Three categories grouped based on the different endotamponades used (C3F8, C2F6, and air) are shown in Table 3. We deleted 7 cases with postoperative complication in order to analyze the improved effect of 3 gases on the structural and functional aspects of MF, without the influence of extreme data (2 FTMH, 1 glaucoma, and 4 complicated cataract). Twenty-eight eyes (50.9%) used C3F8 tamponade, 11 eyes (20.0%) C2F6 tamponade, and the remaining 16 eyes (29.1%) air tamponade. There were no statistically significant differences in age, axial length, CFT, FD, baseline BCVA, change BCVA or cataract treatment in these three groups. However, postoperative BCVA was statistically different among these three groups (P = 0.01, Least Significant Difference test). Eyes treated with air tamponade had better visual outcome than eyes with C3F8 tamponade, with P value of 0.008 (Least Significant Difference test). Postoperative BCVA was not statistically different between groups treated with C2F6 and C3F8 tamponade, nor between C2F6 and air tamponade (P = 0.989, P = 0.019, respectively, Least Significant Difference test). The follow-up period wasn’t statistically different between C3F8 and air tamponade (P = 0.655), but it was significantly longer in C2F6 group than in the other two groups (P = 0.013, P = 0.010, respectively, Least Significant Difference test).

Factors affecting the change in BCVA using multiple linear regression analysis are shown in Table 4. Better postoperative BCVA had a high correlation with better baseline BCVA and absence of FD (P < 0.001, 0.013, multiple linear regression analysis), whereas age, duration of symptoms, axial length, baseline CRT, phacoemulsification, epiretinal membrane, vitreous traction and Lamellar hole were not correlated with final visual outcome. Baseline BCVA (β = 0.579) had greater effect on postoperative BCVA than foveal detachment (β = 0.316).

Complications

FTMH developed in 2 eyes (3.2%). One eye with C2F6 tamponade, FTMH was present at 1 month after surgery, maintained stable postoperative vision without macular detachment or the macular hole progression in 1 year follow-up. Another eye with C3F8 tamponade, FTMH was present at 4 month after surgery, complicated with retinal detachment in the 11th month after surgery, underwent reoperation with silicone oil tamponade. The retina was reattached and MH was closed in the second FTMH eye. One eye developed glaucoma with baseline intraocular pressure (IOP) of 23 mmHg, axial length of 34.92 mm and with C3F8 tamponade (1.6%), recovered with anti-glaucoma medication. Of the 32 eyes in which the lens showed clear preoperatively, cataract developed in 18 eyes (56%), 14 eyes were cured by cataract removal during the follow-up period. The remaining four eyes with postoperative vision deterioration are still under observation. For these 18 eyes, 12 eyes were with C3F8 tamponade, 4 eyes with C2F6 tamponade, and 2 eyes with air tamponade.

Lens status

At the last follow-up, a total of 44 eyes underwent cataract surgery, 5 pseudophakic eyes, 1 aphakic eye, with the remaining 12 being phakic (4 opacity vs. 8 transparent).

Discussion

The results of our study showed that most patients with MF and progressive visual symptoms may obtain anatomical and functional improvement from 23-gauge vitrectomy with ILM peeling at least 6 months following (p < 0.001). Many earlier studies confirmed that PPV with ILM peeling results in better BCVA and anatomic outcomes compared with PPV alone [5, 8, 9, 13, 14, 23,24,25]. However, some researchers hypothesized that total ILM peeling could increase the risk of developing a FTMH, macular shift and inner retinal dimples [5, 26]. FTMH is a common complication after PPV with ILM peeling for MF, with an incidence of about 12.5% ~ 27.3%. In our study, 2 of 62 eyes (3.2%) developed FTMH with total ILM peeling, similar to the incidence of PPV without ILM peeling studies and ‘Fovea-sparing ILM peeling’ studies [27,28,29]. ‘Fovea-sparing ILM peeling’ method was raised by Ho [7] and Shimada [5] to prevent the formation of FTMH and to reduce the damage to the structure of macular after vitrectomy. It’s extremely challenging to preserve a small size of spared-fovea ILM with long axial length. If the size is not small enough or the margin is not sharp, the preserved ILM itself may cause a late contraction [5]. ILM peeling, gas tamponade, and preoperative ellipsoid disruption may be risk factors of the formation of FTMH [13,14,15, 20, 22, 30, 31]. It has been reported that postoperative FTMH is more common in MF with FD [2, 32, 33]. Two of 9 preoperative lamellar MHs in our study that developed postoperative FTMH (one case with C3F8 tamponade, the other one with C2F6 tamponade). Tian’s research showed that 1 of 2 (50%)preoperative lamellar MHs in the fovea-sparing ILM peeling group developed postoperative FTMH and 1 (100%) in the total ILM peeling group. His research believed that the only risk factor for development of postoperative FTMH was preoperative outer lamellar MH, regardless of the surgical procedure selection, fovea-sparing or total ILM peeling [29]. However, in Shimada’s [5] and Ho’s studies [34], no postoperative development of FTMH was found in the fovea-sparing ILM peeling group. We hypothesized that the foveal tissue with lamellar MH or EZ defect is fragile and is more easily damaged by the traction of the surgical retinal reattachment to posterior staphyloma. How to reduce the occurrence of postoperative MH requires further study.

Overall, 43 (69.4%) eyes showed improvement in BCVA in our study. Seven eyes had vision decrease, which was mainly caused by FTMH and complicated cataract. Cataract progression was seen in 18 eyes in our group, of which 14 eyes underwent subsequent cataract surgery and 4 eyes didn’t because of the patients’ own requirement and were under observation in the period of follow-up. The study of Rishi et al. reported that age of the patient, type of intraocular gas, duration of prone positioning, and the effective time of contact of gas bubble with the crystalline lens may be several factors influencing the cataract progression after PPV and gas tamponade [35]. We analyzed BCVA change of 14 eyes with cataract progression in the postoperative period. The majority of 14 eyes had a changing trend in having postoperative vision rising first and then decreasing with progression of cataract; meanwhile, MF had continuous structural improvement. After the subsequent cataract surgery, BCVA of 14 eyes return to the optimal level again during the follow-up period. On balance, foveoschisis resolution was the basis of good postoperative vision, cataract surgery enabled further visual recovery. For patients with preoperative transparent lens, it is necessary to inform them of the possibility of postoperative cataract progression and treat the cataract in time.

In our study, the eyes with FD had a thicker baseline mean CFT and a thinner postoperative mean CFT, compared with those without FD, probably due to EZ disruption preoperatively related to the foveoschisis and FD. This disruptive change may bring about worse preoperative BCVA and postoperative BCVA, compared with those eyes without FD at baseline [31]. Our study showed that a better baseline BCVA and absence of FD were significantly correlated with a better visual prognosis (p < 0.001), similar to the results by Lee et al. [36] and Al-Badawi et al. [37]. Nonetheless, even eyes with FD achieved as much improvement in vision and macular structure as eyes without FD from baseline. Therefore, when the central fovea is affected, with vision decline, it is effective to take surgical treatment of vitrectomy in time to restore the foveal configuration and prevent macular hole and retinal detachment. For eyes with FD with long-term low vision, surgery is still an effective way to improve visual acuity.

Whether or not to use gas tamponade and which gas is more suitable for tamponade has been controversial [14, 20, 38]. Jiang et al. [39] considered that C3F8 was more effective in patients than air. Hwang et al. [18] reported that there was no significant difference in postoperative BCVA between air tamponade group and C3F8 group. In this study, air, C2F6 and C3F8 tamponade were divided into three groups according to different tamponade material. There was no significant difference in FD between the three groups (P = 0.252), which could exclude the effect on the statistical results. All eyes of the three groups showed significant visual improvement after vitrectomy. The air tamponade group showed a greater improvement in postoperative BCVA compared with the C3F8 tamponade group. This was consistent with a better preoperative BCVA and a lower proportion of FD in air tamponade group, although there was no significant difference between the two groups. Moreover, there was no significant difference in the BCVA change between the two groups, indicating that air tamponade was as effective as C3F8 tamponade in treating MF. C2f6 provided tamponading effect for an intermediate duration in the 3 gases, which may be the reason of no significant difference in postoperative BCVA between groups treated with C2F6 and C3F8 tamponade, nor between C2F6 and air tamponade. The longest period of follow-up of C2F6 group may influence little on the comparison of postoperative BCVA among the three groups.

There are several limitations to this study. First, although our surgical technique was standardised, the decision to use either air or expansive gas intraocular tamponade depended on the surgical period (by June 2017) and the surgeon’s experience rather than being driven by particular guidelines. Second, we didn’t note EZ disruption in the study, because some OCT scans were of poor quality caused by lens opacity and extreme axial length. Third, the sample size was not enough, and the patients were not randomized into groups.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that a better baseline BCVA and absence of FD were strongly correlated with a better visual prognosis in the treatment of MF. Most patients with MF may obtain anatomical and functional improvement from vitrectomy with ILM peeling and gas tamponade, regardless of whether FD is present at baseline. Air tamponade can provide as good visual recovery as expansive gas, and reduce postoperative complications.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ILM:

-

Internal limiting membrane

- MF:

-

Myopic foveoschisis

- BCVA:

-

Best-corrected visual acuity

- CFT:

-

Central foveal thickness

- SD-OCT:

-

Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography

- MH:

-

Macular hole

- FTMH:

-

Full-thickness macular holes

- FD:

-

Foveal detachment

- EZ:

-

Ellipsoid zone

- PPV:

-

Pars plana vitrectomy

- LogMAR:

-

Logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution

- IOP:

-

Intraocular pressure

References

Baba T, Ohno-Matsui K, Futagami S, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of foveal retinal detachment without macular hole in high myopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:338–42.

Gaucher D, Haouchine B, Tadayoni R, et al. Long-term follow-up of high myopic foveoschisis: natural course and surgical outcome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:455–62.

Wu PC, Chen YJ, Chen YH, et al. Factors associated with foveoschisis and foveal detachment without macular hole in high myopia. Eye (Lond). 2009;23:356–61.

Takano M, Kishi S. Foveal retinoschisis and retinal detachment in severely myopic eyes with posterior staphyloma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128:472–6.

Shimada N, Sugamoto Y, Ogawa M, Takase H, Ohno-Matsui K. Fovea-sparing internal limiting membrane peeling for myopic traction maculopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154:693–701.

Ho TC, Yang CM, Huang JS, Yang CH, Chen MS. Foveola nonpeeling internal limiting membrane surgery to prevent inner retinal damages in early stage 2 idiopathic macula hole. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;252:1553–60.

Ho TC, Chen MS, Huang JS, Shih YF, Ho H, Huang YH. Foveola nonpeeling technique in internal limiting membrane peeling of myopic foveoschisis surgery. Retina. 2012;32:631–4.

Ikuno Y, Sayanagi K, Soga K, Oshima Y, Ohji M, Tano Y. Foveal anatomical status and surgical results in vitrectomy for myopic foveoschisis. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2008;52:269–76.

Kanda S, Uemura A, Sakamoto Y, Kita H. Vitrectomy with internal limiting membrane peeling for macular retinoschisis and retinal detachment without macular hole in highly myopic eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136:177–80.

Ikuno Y, Sayanagi K, Ohji M, et al. Vitrectomy and internal limiting membrane peeling for myopic foveoschisis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:719–24.

Johnson MW. Myopic traction maculopathy: pathogenic mechanisms and surgical treatment. Retina. 2012;32(Suppl 2):S205–10.

Rey A, Jurgens I, Maseras X, Carbajal M. Natural course and surgical management of high myopic foveoschisis. Ophthalmologica. 2014;231:45–50.

Kobayashi H, Kishi S. Vitreous surgery for highly myopic eyes with foveal detachment and retinoschisis. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1702–7.

Kim KS, Lee SB, Lee WK. Vitrectomy and internal limiting membrane peeling with and without gas tamponade for myopic foveoschisis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:320–6.

Lim SJ, Kwon YH, Kim SH, You YS, Kwon OW. Vitrectomy and internal limiting membrane peeling without gas tamponade for myopic foveoschisis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;250:1573–7.

Fang X, Weng Y, Xu S, et al. Optical coherence tomographic characteristics and surgical outcome of eyes with myopic foveoschisis. Eye (Lond). 2009;23:1336–42.

Fujimoto S, Ikuno Y, Nishida K. Postoperative optical coherence tomographic appearance and relation to visual acuity after vitrectomy for myopic foveoschisis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156:968–73.

Hwang JU, Joe SG, Lee JY, Kim JG, Yoon YH. Microincision vitrectomy surgery for myopic foveoschisis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97:879–84.

Shin JY, Yu HG. Visual prognosis and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography findings of myopic foveoschisis surgery using 25-gauge transconjunctival sutureless vitrectomy. Retina. 2012;32:486–92.

Uchida A, Shinoda H, Koto T, et al. Vitrectomy for myopic foveoschisis with internal limiting membrane peeling and no gas tamponade. Retina. 2014;34:455–60.

Zhang T, Zhu Y, Jiang CH, Xu GZ. Long-term follow-up of vitrectomy in patients with pathologic myopic foveoschisis. Int J Ophthalmol. 2017;10:277–84.

Figueroa MS, Ruiz-Moreno JM, Gonzalez DVF, et al. Long-term ourcomes of 23-gauge pars plana vitrectomy with internal limiting membrane peeling and gas tamponade for myopic traction maculopathy: a prospective study. Retina. 2015;35:1836–43.

Kumagai K, Furukawa M, Ogino N, Larson E. Factors correlated with postoperative visual acuity after vitrectomy and internal limiting membrane peeling for myopic foveoschisis. Retina. 2010;30:874–80.

Sayanagi K, Ikuno Y, Tano Y. Reoperation for persistent myopic foveoschisis after primary vitrectomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:414–7.

Taniuchi S, Hirakata A, Itoh Y, Hirota K, Inoue M. Vitrectomy with or without internal limiting membrane peeling for each stage of myopic traction maculopathy. Retina. 2013;33:2018–25.

Spaide RF. "dissociated optic nerve fiber layer appearance" after internal limiting membrane removal is inner retinal dimpling. Retina. 2012;32:1719–26.

Qi Y, Duan AL, Meng X, Wang N. Vitrectomy without inner limiting membrane peeling for macular retinoschisis in highly myopic eyes. Retina. 2016;36:953–6.

Huang Y, Huang W, Ng DSC, Duan A. Risk factors for development of macular hole retinal detachment after pars plana vitrectomy for pathologic myopic foveoschisis. Retina. 2017;37:1049–54.

Tian T, Jin H, Zhang Q, Zhang X, Zhang H, Zhao P. Long-term surgical outcomes of multiple parfoveolar curvilinear internal limiting membrane peeling for myopic foveoschisis. Eye (Lond). 2018;32:1783–9.

Ikuno Y, Gomi F, Tano Y. Potent retinal arteriolar traction as a possible cause of myopic foveoschisis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:462–7.

Iida Y, Hangai M, Yoshikawa M, Ooto S, Yoshimura N. Local biometric features and visual prognosis after surgery for treatment of myopic foveoschisis. Retina. 2013;33:1179–87.

Hirakata A, Hida T. Vitrectomy for myopic posterior retinoschisis or foveal detachment. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2006;50:53–61.

Shimada N, Ohno-Matsui K, Baba T, Futagami S, Tokoro T, Mochizuki M. Natural course of macular retinoschisis in highly myopic eyes without macular hole or retinal detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:497–500.

Ho TC, Yang CM, Huang JS, et al. Long-term outcome of foveolar internal limiting membrane nonpeeling for myopic traction maculopathy. Retina. 2014;34:1833–40.

Rishi P, Rishi E, Bhende P, et al. A prospective, interventional study comparing the outcomes of macular hole surgery in eyes randomized to C3F8, C2F6, or SF6 gas tamponade. Int Ophthalmol. 2022.

Lee DH, Moon I, Kang HG, et al. Surgical outcome and prognostic factors influencing visual acuity in myopic foveoschisis patients. Eye (Lond). 2019;33:1642–8.

Al-Badawi AH, Abdelhakim M, Macky TA, Mortada HA. Efficacy of non-fovea-sparing ILM peeling for symptomatic myopic foveoschisis with and without macular hole. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;103:257–63.

Panozzo G, Mercanti A. Vitrectomy for myopic traction maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:767–72.

Jiang J, Yu X, He F, Lu L, Wang Z. Treatment of myopic foveoschisis with air versus perfluoropropane: a retrospective study. Med Sci Monit Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2017;23:3345–52.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LW and ZJY designed the whole study. ZJY and YYP collected all the data and conducted data analysis with DDS. ZJY drafted the manuscript and revised with LW and YYP. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Beijing Tongren Hospital Review Board. And as a retrospective study, the informed consent waiver was approved by the Beijing Tongren Hospital Review Board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Yu, Y., Dai, D. et al. Vitrectomy with internal limiting membrane peeling and gas tamponade for myopic foveoschisis. BMC Ophthalmol 22, 214 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-022-02376-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-022-02376-0