Abstract

Background

Demographic, systemic and ocular factors may impact macular ganglion cell–inner plexiform layer (GCIPL) thickness measurements. This study aimed to investigate the influences of multiple potential determinants of macular GCIPL thickness in normal Chinese adults.

Methods

This was a retrospective study conducted on 225 normal eyes from 225 healthy Chinese adults. GCIPL thickness were obtained using Cirrus high-definition optical coherence tomography (OCT). The age, gender, laterality, spherical equivalent (SE) refractive error, intraocular pressure (IOP), axial length (AL), central cornea thickness (CCT), circumpapillary retinal nerve fibre layer (pRNFL) thickness and OCT signal strength were recorded and their respective effect on GCIPL thickness parameters were evaluated.

Results

The mean (± SD) average, minimum, superotemporal, superior, superonasal, inferonasal, inferior, and inferotemporal GCIPL thickness was 84.56 ± 5.36, 81.32 ± 5.58, 83.08 ± 5.37, 85.70 ± 5.95, 87.15 ± 6.26, 85.07 ± 6.11, 82.46 ± 5.76, and 83.88 ± 5.59 μm, respectively. Determinants of thinner GCIPL thickness were older age (P = 0.001–0.117; effects enhanced if age over 40 years), thinner pRNFL (all P < 0.001), and weaker signal strength (all P < 0.001). No significant difference was found between males and females (P = 0.069–0.842), and between right eyes and the left eyes (P = 0.160–0.875) except that of superonasal GCIPL thickness (P < 0.001). There was no significant correlation between GCIPL thickness and SE, IOP, CCT, and AL (P = 0.135–0.968).

Conclusions

Individual determinants associated with thinner GCIPL thickness were older age (particularly over 40 years of age), thinner pRNFL, and weaker OCT signal strength. This is relevant in comprehensively understanding the normative data and differentiating normal aging from abnormalities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Glaucoma is one of the leading causes of irreversible blindness worldwide. The hallmark of glaucoma is progressive loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) in the inner retina and their axons in the optic nerve head (ONH) [1]. Previous studies have showed that structural glaucomatous changes primarily affect RGCs and their axons, followed by functional changes featured by characteristic glaucomatous visual field defect [2]. There may be a 20–40% of RGC loss prior to detectable visual field defect, indicating that evaluation of RGCs could be beneficial in detection and monitoring of glaucoma [3].

As the output neurons of the retina, RGCs are the only part of the central nervous system that can be optically detected in vivo [4]. The human retina contains an estimate of more than 1 million RGCs, over 50% of which locate in the macular, making it the easiest region for calculating the RGC counts and detecting their loss [5]. The thinning of macular ganglion cell layer (GCL) and peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (pRNFL) has been well recognized as biomarkers of optic nerve damage, which can be quantitatively measured by optical coherence tomography (OCT) in a non-invasive, precise, and reproducible way.

A number of studies have showed that the macular ganglion cell complex (GCC, the sum of RNFL, GCL, and inner plexiform layer) thickness or the macular ganglion cell–inner plexiform layer (GCIPL) thickness has similar glaucoma discriminating performance with that of pRNFL [6,7,8,9]. Combining GCC/GCIPL thickness, pRNFL thickness, ONH parameters, psychophysics examinations, and vasculature evaluations, though, can help to improve the overall glaucomatous diagnostic ability and accuracy [10].

For clinical interpretation of GCC/GCIPL and pRNFL thickness readings, it is essential to know physiological factors that could influence these measurements. In normal eyes, age, sex, ethnicity, refractive power, axial length, optic disc size, OCT scanning mode and signal strength have been proven to be associated with GCC/GCIPL and/or pRNFL thickness; among these, age is considered to be the most significant determinant [11,12,13,14]. However, some of the previous studies investigated multiple potential determinants with limited analysis deep into each determinant, and some emphasized on one or two determinants. Thus, studies that are more comprehensive is needed to investigate which factors impact the OCT readings and how much the impacts are. The purpose of this study was to examine the influences of multiple demographic and ocular factors on the measurements of macular GCIPL thickness using Cirrus high-definition optical coherence tomography in a cohort of normal Chinese adults with detailed, comprehensive analyses.

Methods

In this retrospective, observational study, all participants were consecutively recruited from the Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China, from February 2013 to January 2016. The study followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after explanation of the nature and possible consequences of the study.

Eligibility was determined via demographic characteristics recording and a comprehensive ophthalmologic evaluation including measurement of uncorrected and best-corrected visual acuity, measurement of refractive error (cycloplegic refraction test for participants younger than 30-year-old, and manifest refraction test for participants of 30 years or older), slit lamp biomicroscopy examination, intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement using a Goldman applanation tonometer (Haag-Streit, Bern, Switzerland), angle evaluation using gonioscopy, dilated fundus examination, stereo disc photography (Kowa nonmyd a-D III; Kowa Optimed Inc., Aichi, Japan), visual field testing (Humphrey Visual Field Analyzer II; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA) using the Swedish Interactive Thresholding Algorithm (SITA) standard 24–2 program, and OCT scanning (Cirrus HD-OCT; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA).

For inclusion, the criteria were: (1) generally healthy individuals of age ≥ 18 years; (2) best-corrected visual acuity 20/20 or better; (3) a spherical equivalent (SE) refractive error between − 5.00 diopters (D) and + 1.00 D, astigmatism between − 1.00 D and + 1.00 D, and bilateral refractive difference of no more than 1.50 D in SE; (4) intraocular pressure < 21 mmHg; (5) normal and wide anterior chamber angle; (6) normal optic nerve head appearance (cup-to-disc ratio < 0.5 in either eye, with the asymmetry of ≤0.2, no evidence of optic disc hemorrhage or focal thinning of the rim); (7) reliable and normal visual field results which was defined as: mean deviation (MD) with a P value of > 5%, pattern standard deviation (PSD) with a P value of > 5%, no more than 3 adjacent points in the pattern deviation plot with a P value of < 5%, and glaucoma hemifield test within the normal range; besides, the test should have a false-positive error, a false-negative error, and a fixation loss of less than 15%, simultaneously. The appearance of the optic disc on stereoscopic fundus photographs and visual field results were evaluated independently by two glaucoma specialists (XX and HX) who were masked to all other information about the eyes. Inconsistencies between these two doctors were decided by a senior glaucoma expert (XL). The data of the eye would not be used if the three doctors did not reach an agreement on the classification.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) any known history of ocular disorders except mild or moderate refractive error; (2) history of ocular and/or brain trauma; (3) previous intraocular surgery; (4) optic media opacity; (5) medications usage or toxicosis that may cause IOP elevation or induce optic neuropathy; (6) neurological or systemic disorders that potentially affect visual field results and/or OCT readings, such as intracranial mass lesions, cerebrovascular diseases, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, multiple sclerosis, radiation encephalopathy and optic neuropathy; (7) unsatisfactory image acquisition; (8) inability to cooperatively complete all examinations.

Participants were enrolled only if both eyes met the inclusion criteria. Both eyes were studied. Except for the comparisons of GCIPL thickness between right and left eyes, data from one randomly selected eye of each participant were used for analyses.

Eligible participants underwent central cornea thickness (CCT) measurement using Ultrasonic Pachymetry (DGH-1000, Storz Inc., Louis, MO, USA) and the axial length (AL) measurement using IOLMaster (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA).

OCT images were obtained after eyes were dilated with tropicamide 1% and phenylephrine 2.5% (Mydrin®-P, Santen Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan) using the same OCT device by a well-trained glaucoma specialist (XX). Macular Cube 200 × 200 scan (200 horizontal B-scans comprising 200 A-scans per B-scan within a cube measuring 6 × 6 × 2 mm centered on the fovea) and Optic Disc Cube 200 × 200 scan (200 horizontal B-scans comprising 200 A-scans per B-scan within a cube measuring 6 × 6 × 2 mm centered on the optic disc center) were performed respectively at the same visit. Artificial tear was provided if the participants complained dryness or discomfort. Images with signal strength of less than 6 and those with visible motion or blinking artifacts and obvious segmentation failure were discarded immediately followed by repetition(s) of the scan.

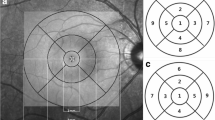

The distance between the inner boundary of the GCL and the outer boundary of the IPL yields the combined thickness of the GCL and IPL (termed “GCIPL”) by the ganglion cell analysis (GCA) algorithm. The GCIPL thickness were analyzed within an elliptical annulus area of 14.13 mm2 with a horizontal inner and outer radius of 0.6 and 2.4 mm, respectively; and a vertical inner and outer radius of 0.5 mm and 2.0 mm, respectively. The average, minimum, and 6 sectoral (superior, superonasal, inferonasal, inferior, inferotemporal, and superotemporal) GCIPL thickness parameters were calculated. The minimum GCIPL thickness was defined as the lowest measured value of the 1-degree intervals among all the 360 spokes. The average RNFL and quadrant (superior, temporal, inferior and nasal) circumpapillary RNFL thickness were calculated by the Cirrus analysis algorithm.

Participants were divided into 6 groups by age with an interval of 10 years. Participants were also divided into 2 groups based on refractive error: emmetropia group (SE between − 0.5D to + 1.0D) and myopia group (SE of <− 0.5D and ≥ − 5.0D).

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Shapiro-Wilk test and Levene test were applied to test the normality and the homogeneity of variance, respectively. Comparisons of GCIPL thickness between different gender and refractive groups were performed using independent-samples t-test. Paired-samples t-test was used to evaluate the GCIPL thickness between the right eye and the left eye of each subject. Comparisons of the GCIPL thickness and refraction between multiple age groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni adjustment for pairwise comparisons. Correlations between GCIPL thickness and the following factors were analyzed using Pearson correlation coefficient: age, SE refractive error, IOP, CCT, AL, and OCT signal strength. Univariate linear regression analyses were performed to assess how age and the average pRNFL thickness affected GCIPL thickness, respectively. As age itself may impact pRNFL thickness and OCT signal strength, multicollinearity between age and pRNFL thickness, and between age and signal strength was diagnosed using variance inflation factor (VIF), respectively. A VIF of 1 means there is no multicollinearity in the regression model. A VIF above 4 indicates that multicollinearity might exist, and a VIF above 10 indicates that there is significant multicollinearity. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Except where stated otherwise, the data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) values.

Results

A total of 225 participants (96 males and 129 females) were enrolled. The mean age of the study population was 46.3 ± 16.5 years (range from 18 to 75 years of age). The average, minimum, superotemporal, superior, superonasal, inferonasal, inferior, and inferotemporal GCIPL thickness was 84.56 ± 5.36, 81.32 ± 5.58, 83.08 ± 5.37, 85.70 ± 5.95, 87.15 ± 6.26, 85.07 ± 6.11, 82.46 ± 5.76, and 83.88 ± 5.59 μm, respectively. Variability of GCIPL thickness were assessed upon the following possible determinants:

Gender

The mean age of 96 males and 129 females was 45.9 ± 16.7 and 47.6 ± 16.8 years, respectively. Independent-samples t-test of the age difference between genders showed no statistical significance (P = 0.576). No statistically significant differences were found of average, minimum, and sectoral GCIPL thickness between genders (Table 1).

Laterality

Table 2 presented the comparisons of the variability between right and left eyes of all subjects, showing qualitatively similar GCIPL thickness in fellow eyes except that of the superonasal sector, where the left eyes yielded significant thicker GCIPL than the right eyes.

Age

The grouping of six age groups, and the GCIPL measurements of each group with group-wise comparison results were presented in Table 3. GCIPL thickness increased slowly with age in younger adults and reached its peak at 40–49 years of age. Thereafter, it decreased rapidly with age. Pairwise comparisons showed statistically significant difference in each GCIPL parameter between Group 4 and Group 5, and between Group 4 and Group 6. Given that the refractive error may have potential impacts on GCIPL thickness independent of other factors, refraction status of each age group was evaluated. The SE from Group 1 to 6 was (− 2.89 ± 1.83) D, (− 0.11 ± 1.67) D, (0.45 ± 0.54) D, (− 0.20 ± 0.95) D, (− 0.19 ± 1.03) D, and (0.70 ± 1.79) D. One-way ANOVA showed statistically significant difference among the 6 groups (P < 0.001). Statistically significant differences in SE was found in further pairwise comparisons between Group 1 and other 5 groups (all P < 0.001), whereas no significant difference was found between Group 2 to 6, respectively (P = 0.083–0.969).

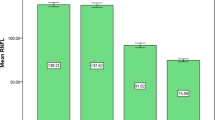

There was a negative correlation between GCIPL thickness and age. Statistical significance was found in all analyses except that between the inferotemporal GCIPL thickness and age. Significant negative correlation of GCIPL thickness and age was found in all GCIPL parameters but superotemporal GCIPL thickness in subjects of 40 years or older (Table 4). Regression analyses performed in 139 subjects older than 40 years showed that GCIPL thickness parameters were predictable by age (Fig. 1). For example, average GCIPL thickness decreased by 0.229 μm for every 1 year increase in age.

IOP, AL, and CCT

Mean IOP was (14.3 ± 2.5) mm Hg (ranging from 9 to 19 mmHg). Mean AL was (23.84 ± 0.85) mm (ranging from 22.12 to 26.24 mm). Mean CCT was (554.1 ± 27.1) μm (ranging from 497 to 628 μm). No statistically significant correlation was found between each GCIPL parameter with IOP, AL, or CCT (Table 5).

Refractive error

Of all the 225 eyes enrolled in this study, mean SE refractive error was (− 0.57 ± 1.88) D, ranging from − 5.00D to + 1.00D. No statistically significant correlation was found between each GCIPL parameter and SE (Table 5, last 2 columns). All participants were also divided into emmetropic group (122 eyes, mean SE of 0.60 ± 0.85 D, mean age of 48.5 ± 6.6 years) and myopic group (103 eyes, mean SE of − 2.38 ± 1.57 D, mean age of 42.7 ± 9.4 years). No statistically significant difference in age was found between the two groups (P = 0.181). Statistically significant differences were found in inferonasal and inferior GCIPL thickness only (P = 0.008 and 0.024, respectively; Table 6).

RNFL thickness

The mean average, superior, temporal, inferior, and nasal RNFL thickness was (98.08 ± 9.17) μm (range: 82 to 125 μm), (123.99 ± 15.42) μm (range: 94 to 187 μm), (71.83 ± 10.76) μm (range: 55 to 102 μm), (130.17 ± 16.65) μm (range: 102 to 191 μm), and (66.25 ± 10.08) μm (range 42 to 95 μm), respectively. Statistically significant positive correlation was found between all GCIPL thickness parameters and average RNFL thickness (all P < 0.001). More correlation analyses were conducted between each GCIPL thickness parameter and the superior, temporal, inferior, and nasal RNFL thickness, respectively (Table 7). Regression analyses showed that mean RNFL thickness was predictable by GCIPL thickness parameters (Fig. 2). For example, the average RNFL thickness decreased by 0.901 μm for every 1 μm decrease in average GCIPL thickness. Further analysis of possible impacts of age on average RNFL thickness was performed using multivariate linear regression model. Multicollinearity diagnosis showed that the VIF was 1.053 in this model, indicating no significant multicollinearity was found.

OCT signal strength

The average signal strength of macular cube 200 × 200 scanning protocol was (8.40 ± 1.22). Based on that, the correlation between the signal strength and the GCIPL thickness was analyzed and statistically significant positive correlation was found in all GCIPL thickness parameters (Table 8). Further analysis of possible impacts of age on signal strength was performed using multivariate linear regression model. Multicollinearity diagnosis showed that the VIF was 1.029 in this model, indicating no significant multicollinearity was found.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated multiple determinants of macular GCIPL thickness in normal Chinese adults and demonstrated that GCIPL thinning was associated with older age, thinner pRNFL, and weaker OCT scanning signal strength. In general, gender, laterality, refractive status (when the refractive error is between +1D and -5D), IOP, CCT, and AL had no significant impacts on macular GCIPL thickness.

Age was one of the most significant impact factors in determining macular GCIPL thickness. In this study, we found that the overall trend of GCIPL thickness changing with age was as follows: GCIPL thickness increased slowly with age in younger adults; after reaching the peak at 40–49 years of age, it decreased rapidly with age, which was consistent with the findings of Mwanza et al. [14] However, previous studies involving Asian populations showed that pRNFL thickness was comparatively thicker in teenagers and reached its peak at 20–29 years of age, then gradually became thinner [15, 16]. These findings suggested that GCIPL and RNFL thickness changes may not necessarily be synchronized.

We found that for each additional year over 40 years of age, average, minimum, superotemporal, superior, superonasal, inferonasal, inferior, and inferotemporal GCIPL thickness decreased by 0.229, 0.200, 0.127, 0.249, 0.273, 0.295, 0.273, and 0.173 μm, respectively. Animal experiments demonstrated that the age-related change of RGC predominately manifested as axon loss, while the RGC cell count is relatively constant [17]. As the retina expands with age while the total cell counts retain, the RGC density decreases. The phenomenon of retina expansion with age was also found in human eyes, but the main difference with the animal eyes was that the number of RGC soma also declined with age in human [18]. Therefore, it is explainable that the GCIPL gets thinner with age in an OCT-based thickness evaluation, as shown in this study. It has been proven by multiple studies that GCC or GCIPL thickness decreased with age, even though the age-related RGC loss rate varies. Annual RGC loss rate was between 0.07 to 0.61%, as reported in studies with the sample size between 12 eyes to 72 eyes [19,20,21,22,23]. In this study, we further approved that the age-dependent GCIPL thickness change was nonlinear with age. However, this age-related variability of the OCT measurements may not be completely attributed to inter-subject variability, which is considerably significant even in normal populations. When ganglion cells reduce with age, the migrant amacrine cells and other non-neuronal components may partially compensate the space which is previously predominated by ganglion cells. As such, the actual cell loss may be masqueraded and the age-RGC loss correlation may become more unpredictable. Moreover, ganglion cells layer in the macular region, making it more complicated to evaluate the defined pattern of region- and eccentricity-associated, age-dependent RGC loss.

When evaluating the potential causative impacts of axial length on GCIPL thickness, contradictory conclusions were drawn, which was similar to RNFL thickness. Some studies proposed that the GCIPL and RNFL thickness were negatively correlated to axial length [24,25,26,27]. Studies with a larger sample size and/or a wider range of refractive status, generally indicated that only less than 0.5% GCIPL thickness change was attributed to per millimeter axial length change [13, 14]. Such minor changes could hardly reflect any practical clinical significance. Another reason that axial length may have some impacts on the GCIPL thickness measurement, but not necessarily the actual anatomic cell counts may be ascribed to the optical effects. Since the Cirrus OCT model eye adopts a calibrated value of 24.46 mm as the default axial length setting with a fixed measuring angular distance of approximately 12°, the actual scanning area would be larger than the “standard” retinal area due to the optical magnification effect in eyes longer than 24.46 mm. As the macular ganglion cell counts drop dramatically as the eccentricity increases outward from the foveal center, average ganglion cell estimates or GCIPL thickness in these eyes may therefore be underestimated. On the contrary, in eyes shorter than 24.46 mm, the actual scanning area is smaller than the preset area where the ganglion cells are more crowded and thus a thicker GCIPL measurement may be falsely generated.

Other studies declined the direct impacts of axial length on RGC growth or apoptosis and claimed that axial length had no significant correlation with macular GCIPL thickness [28, 29], which our findings was consistent with. The relatively small sample size could be one possible cause. Also, our inclusive criteria for spherical equivalent refractive error were − 5.00 D and + 1.00 D. The exclusion of highly myopic eyes restricted the variability of axial length, thus minimizing the interference of magnification effects on location of the retinal area being scanned that could potentially influence the GCIPL thickness measurements. Similarly, no significant association between refractive error and GCIPL thickness was found in our study. The difference of average, minimum, and most sectoral GCIPL thickness between the two refractive groups were not statistically significant, except that in inferonasal and inferior sectors. Histological studies of both human and animals have found that the RGC were denser nasally than temporally, and superiorly than inferiorly, with distinct inter-subject variability, which might have indicated the discrepant anatomic distribution pattern in emmetropic and myopic eyes [30]. The thickest GCIPL was detected in the superonasal sector, where no significant difference in emmetropic and myopic groups was found, suggesting that the density in this sector may have partially offset the difference caused by refractive error and/or axial length. This sector may have poorer performance in diagnosing glaucoma due to its least glaucomatous susceptibility.

In a cohort of participants that no significant correlation between age and pRNFL thickness was found, the finding that pRNFL thickness had statistically significant positive correlation with macular GCIPL thickness was not surprising and was consistent with previous studies [14, 31]. The axon and soma of the ganglion cells are closely related cellular components, and both can be remarkably affected by glaucoma. Thus, GCIPL and pRNFL thickness are both important and sensitive for early detection of glaucoma. The regression analysis showed that the average RNFL thickness decreased by 0.901 μm for every 1 μm decrease in average GCIPL thickness. Overk et al. [32] found that lesions in the axon may occur earlier than in the soma in some neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, indicating a ‘reverse’ pathogenesis pathway for the primary causative factor of glaucoma. In the pathophysiological development process of glaucoma, whether GCIPL is affected primarily and causes changes in pRNFL, or vice versa, still needs further investigations.

The stronger the OCT signal strength, the deeper retinal tissue the light achieved. As the reflection of the boundaries got enhanced, the segmentation of each layer was more accurate. We found that OCT signal strength was positively correlated to macular GCIPL thickness. Likewise, the signal strength of Cirrus OCT was found to be positively correlated with RNFL thickness [33]. Even though age and OCT signal strength was not correlated in our study, the impact of age on OCT signal strength was notable in clinical practice. Attempts for reaching higher OCT signal strength are recommended to minimize possible underestimate of GCIPL thickness, especially in older populations.

There were several limitations of this study. First, it was a cross-sectional, retrospective study with a comparatively small sample size. Analyses based on a larger sample size is essential to provide more reliable evidence in standardizing clinical interpretation. Second, the subjects were not strictly matched. For instance, the refractive error in the first age group differed significantly with other 5 age groups, while the age of the emmetropic group and the myopic group differed, as well. Third, only ocular predictors were evaluated. Systemic predictors such as history of diabetes, cigarette smoking history, blood pressure, serum lipid levels should be taken into account. More comprehensive investigations are expected in future studies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the GCIPL thickness measured by Cirrus OCT in normal Chinese subjects was associated with age, RNFL thickness, and signal strength of OCT scanning. No significant association was found between GCIPL thickness and gender, laterality, refractive status, intraocular pressure, axial length, and central corneal thickness. These should be considered when making clinical interpretation of GCIPL thickness.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- GCIPL:

-

Ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer

- OCT:

-

Coherence tomography

- SE:

-

Spherical equivalent

- IOP:

-

Intraocular pressure

- AL:

-

Axial length

- CCT:

-

Central cornea thickness

- pRNFL:

-

Peripapillary retinal nerve fibre layer

- RGC:

-

Retinal ganglion cell

- ONH:

-

Optic nerve head

- GCL:

-

Ganglion cell layer

- GCC:

-

Ganglion cell complex

- MD:

-

Mean deviation

- PSD:

-

Pattern standard deviation

References

Kang JH, Wu J, Cho E, Ogata S, Jacques P, Taylor A, et al. Contribution of the Nurses' health study to the epidemiology of cataract, age-related macular degeneration, and Glaucoma. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(9):1684–9. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303317.

Davis BM, Crawley L, Pahlitzsch M, Javaid F, Cordeiro MF. Glaucoma: the retina and beyond. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;132(6):807–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-016-1609-2.

Esporcatte BLB, Kara-Jose AC, Melo LAS Jr, Pinto LM, Tavares IM. The estimates of retinal ganglion cell counts performed better than isolated structure and functional tests for Glaucoma diagnosis. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:2724312.

Smith CA, Chauhan BC. In vivo imaging of adeno-associated viral vector labelled retinal ganglion cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1490. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19969-9.

Rolle T, Dallorto L, Bonetti B. Retinal and macular ganglion cell count estimated with optical coherence tomography RTVUE-100 as a candidate biomarker for Glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(13):5772–9. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.15-18882.

Ustaoglu M, Solmaz N, Onder F. Discriminating performance of macular ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer thicknesses at different stages of glaucoma. Int J Ophthalmol. 2019;12(3):464–71. https://doi.org/10.18240/ijo.2019.03.18.

Oddone F, Lucenteforte E, Michelessi M, Rizzo S, Donati S, Parravano M, et al. Macular versus retinal nerve Fiber layer parameters for diagnosing manifest Glaucoma: a systematic review of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(5):939–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.12.041.

Mwanza JC, Budenz DL, Godfrey DG, Neelakantan A, Sayyad FE, Chang RT, et al. Diagnostic performance of optical coherence tomography ganglion cell--inner plexiform layer thickness measurements in early glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(4):849–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.10.044.

Takayama K, Hangai M, Durbin M, Nakano N, Morooka S, Akagi T, et al. A novel method to detect local ganglion cell loss in early glaucoma using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(11):6904–13. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.12-10210.

Mwanza JC, Budenz DL. Optical coherence tomography platforms and parameters for glaucoma diagnosis and progression. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2016;27(2):102–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICU.0000000000000231.

Huo YJ, Guo Y, Li L, Wang HZ, Wang YX, Thomas R, et al. Age-related changes in and determinants of macular ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer thickness in normal Chinese adults. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;46(4):400–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/ceo.13067.

Zhang X, Francis BA, Dastiridou A, Chopra V, Tan O, Varma R, et al. Longitudinal and cross-sectional analyses of age effects on retinal nerve Fiber layer and ganglion cell complex thickness by Fourier-domain OCT. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2016;5(2):1. https://doi.org/10.1167/tvst.5.2.1.

Koh VT, Tham YC, Cheung CY, Wong WL, Baskaran M, Saw SM, et al. Determinants of ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer thickness measured by high-definition optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(9):5853–9. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.12-10414.

Mwanza JC, Durbin MK, Budenz DL, Girkin CA, Leung CK, Liebmann JM, et al. Profile and predictors of normal ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer thickness measured with frequency-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(11):7872–9. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.11-7896.

Mansoori T, Balakrishna N. Effect of aging on retinal nerve Fiber layer thickness in Normal Asian Indian eyes: a longitudinal study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2017;24(1):24–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09286586.2016.1255762.

Ho H, Tham YC, Chee ML, Shi Y, Tan NYQ, Wong KH, et al. Retinal nerve Fiber layer thickness in a multiethnic Normal Asian population: the Singapore epidemiology of eye diseases study. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(5):702–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.11.031.

Fortune B, Cull G, Reynaud J, Wang L, Burgoyne CF. Relating retinal ganglion cell function and retinal nerve Fiber layer (RNFL) Retardance to progressive loss of RNFL thickness and optic nerve axons in experimental Glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(6):3936–44. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.15-16548.

Calkins DJ. Age-related changes in the visual pathways: blame it on the axon. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(14):ORSF37–41.

Mikelberg FS, Drance SM, Schulzer M, Yidegiligne HM, Weis MM. The normal human optic nerve. Axon count and axon diameter distribution. Ophthalmology. 1989;96(9):1325–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0161-6420(89)32718-7.

Jonas JB, Schmidt AM, Muller-Bergh JA, Schlotzer-Schrehardt UM, Naumann GO. Human optic nerve fiber count and optic disc size. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33(6):2012–8.

Harman A, Abrahams B, Moore S, Hoskins R. Neuronal density in the human retinal ganglion cell layer from 16-77 years. Anat Rec. 2000;260(2):124–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0185(20001001)260:2<124::AID-AR20>3.0.CO;2-D.

Kerrigan-Baumrind LA, Quigley HA, Pease ME, Kerrigan DF, Mitchell RS. Number of ganglion cells in glaucoma eyes compared with threshold visual field tests in the same persons. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(3):741–8.

Repka MX, Quigley HA. The effect of age on normal human optic nerve fiber number and diameter. Ophthalmology. 1989;96(1):26–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0161-6420(89)32928-9.

Chen CY, Huang EJ, Kuo CN, Wu PL, Chen CL, Wu PC, et al. The relationship between age, axial length and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in the normal elderly population in Taiwan: the Chiayi eye study in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0194116. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194116.

Kausar A, Akhtar N, Afzal F, Ali K. Effect of refractive errors/axial length on peripapillary retinal nerve fibre layer thickness (RNFL) measured by Topcon SD-OCT. J Pak Med Assoc. 2018;68(7):1054–9.

Dhami A, Dhasmana R, Nagpal RC. Correlation of retinal nerve Fiber layer thickness and axial length on Fourier domain optical coherence tomography. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(4):NC15–7. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2016/15038.7672.

Bedggood P, Mukherjee S, Nguyen BN, Turpin A, McKendrick AM. Geometry of the retinal nerve fibers from Emmetropia through to high myopia at both the temporal raphe and optic nerve. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60(14):4896–903. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.19-27539.

Barrio-Barrio J, Noval S, Galdos M, Ruiz-Canela M, Bonet E, Capote M, et al. Multicenter Spanish study of spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in normal children. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91(1):e56–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-3768.2012.02562.x.

Prakalapakorn SG, Freedman SF, Lokhnygina Y, Gandhi NG, Holgado S, Chen BB, et al. Longitudinal reproducibility of optical coherence tomography measurements in children. J AAPOS. 2012;16(6):523–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.08.011.

Curcio CA, Allen KA. Topography of ganglion cells in human retina. J Comp Neurol. 1990;300(1):5–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.903000103.

Choi JA, Shin HY, Park HL, Park CK. The pattern of retinal nerve Fiber layer and macular ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer thickness changes in Glaucoma. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:6078365.

Overk CR, Masliah E. Pathogenesis of synaptic degeneration in Alzheimer's disease and Lewy body disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;88(4):508-16.

Russell DJ, Fallah S, Loer CJ, Riffenburgh RH. A comprehensive model for correcting RNFL readings of varying signal strengths in cirrus optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(11):7297–302. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.14-14993.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This project was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81800879), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2021A1515011653 and 2017A030310372). None of the funding bodies played a role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design (XL); data collection (XX, HX, JL); analysis and interpretation of data (XX, HX, KL, XG); statistical analysis (XX); literature search (XX); writing the article (XX); critical revision of the article (XX, HX, KL, XG, JL, XL). All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center of Sun Yat-sen University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from all participants of this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, X., Xiao, H., Lai, K. et al. Determinants of macular ganglion cell–inner plexiform layer thickness in normal Chinese adults. BMC Ophthalmol 21, 267 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-021-02023-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-021-02023-0