Abstract

Background

Core Outcome Sets (COS) are defined as the minimum sets of outcomes that should be measured and reported in all randomised controlled trials to facilitate combination and comparability of research. The aim of this review is to produce an item bank of previously reported outcome measures from published studies in amblyopia, strabismus and ocular motility disorders to initiate the development of COS.

Methods

A review was conducted to identify articles reporting outcome measures for amblyopia, strabismus and ocular motility disorders. Using systematic methods according to the COMET handbook we searched key electronic bibliographic databases from 1st January 2011 to 27th September 2016 using MESH terms and alternatives indicating the different subtypes of amblyopia, strabismus and ocular motility disorders in relation to treatment outcomes and all synonyms. We included Cochrane reviews, other systematic reviews, controlled trials, non-systematic reviews and retrospective studies. Data was extracted to tabulate demographics of included studies, primary and secondary outcomes, methods of measurement and their time points.

Results

A total of 142 studies were included; 42 in amblyopia, 33 in strabismus, and 68 in ocular motility disorders (one study overlap between amblyopia and strabismus). We identified ten main outcome measure domains for amblyopia, 14 for strabismus, and ten common “visual or motility” outcome measure domains for ocular motility disorders. Within the domains, we found variable nomenclature being used and diversity in methods and timings of measurements.

Conclusion

This review highlights discrepancies in outcome measure reporting within published literature for amblyopia, strabismus and ocular motility and it generated an item bank of the most commonly used and reported outcome measures for each of the three conditions from recent literature to start the process of COS development. Consensus among all stakeholders including patients and professionals is recommended to establish a useful COS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Amblyopia, strabismus and ocular motility disorders occur in about 10% of the general population (amblyopia 2–5%, strabismus 4%) [1]. They often present as childhood conditions and can constitute long-term problems for children and young adults. Strabismus and ocular motility disorders can also develop as acquired conditions due to neurological, endocrine and traumatic causes. There are several approaches to the management of these conditions including occlusion, penalisation, spectacles, prisms, drugs, surgery, botulinum toxin, exercises, watchful waiting, or a combination of two or more of the above [2]. The effects from these treatments such as improvements in symptoms or side effects are assessed by outcome measures and are usually used to formally evaluate management options in clinical studies. However varied outcome measures and several endpoints are often used [3,4,5]. This lack of standardisation makes it difficult to compare the conclusions of these studies and, as a result, renders it challenging to discuss realistically the likely outcomes of treatment with patients in the clinic [6].

One strategy suggested to overcome the issues resulting from variable outcome measures is the development of Core Outcome Sets (COS). This is defined as the minimum set of outcomes that should be measured and reported in all randomised controlled trials [7]. The COS will make it easier for the results of trials to be compared, contrasted and combined, lead to research that is more likely to have measured relevant outcomes due to involvement of relevant stakeholders, and enhance the value of evidence synthesis by ensuring that all trials contribute usable information [7]. Therefore, it is postulated that the use of COS would increase the potential in carrying out future meta-analysis for target conditions.

The numerous and diverse outcome measures that may be used for amblyopia, strabismus and ocular motility disorders include, amongst others, visual acuity, angle of deviation, range of ocular movements, fixation stability and binocular vision measurements. There are a number of Cochrane systematic reviews that consider a range of treatment trials for amblyopia, strabismus and ocular motility disorders. Their recommendations call for clarification of dose/response effect and further investigation of treatment regimens [2,3,4]. An attempt to utilise a COS is evident for the National Strabismus Data Set project [8]. A recent review recommended four outcomes for reporting results of surgery for intermittent exotropia [5] but was limited by the extent of literature review and lack of external consensus. A short narrative review of outcome measurements for size of deviation showed considerable variability across the tests available and the recommendations for their use [9].

Development of a COS involves a number of stages that commence with a systematic review of the literature to identify existing knowledge about outcome measures [7]. This is then followed by qualitative studies, Delphi surveys to consult widely on outcome measures and finally, consensus meetings to discuss and agree on the COS [7]. This paper reports the first stage – the literature review to identify the reported range of outcome measures in the published literature for amblyopia, strabismus and ocular motility disorders.

Objectives

The primary aim of this review is to generate an item bank of relevant outcome measures previously reported by researchers and clinicians in studies of treatment of conditions under evaluation. The review aims also to determine the variation in measuring methods used and timings of assessments.

The secondary objectives of this review are to investigate sources of variability of outcome measure definitions including different age groups, study designs, types of amblyopia (e.g. refractive, strabismic, stimulus deprivation), types of strabismus (e.g. exotropia, esotropia), and types of ocular motility disorder (e.g. accommodation and convergence disorders, mechanical restrictions, myogenic, neurogenic, nystagmus, patterns deviation and gaze palsy).

Methods

A protocol for the development of this COS project was written by a steering committee – a team of stakeholders including COS developers, ophthalmologists, orthoptists and journal editors. The review protocol was registered in the COMET initiative website (http://www.comet-initiative.org/studies/details/900?result=true) and published as open access (http://pcwww.liv.ac.uk/~rowef/index_files/Page356.htm). The review, using systematic rigorous methods, was conducted in accordance with the guidelines from the COMET handbook [7]. A PRISMA checklist [10] has been completed for the systematic review and can be found in Additional file 1 : Table S1.

Eligibility criteria

Age

Subjects of all ages with target conditions were included.

Target conditions:

-

1.

Amblyopia (unilateral, bilateral) of any type or severity (refractive, meridional, ametropic, strabismic or stimulus deprivation).

-

2.

Strabismus (latent, manifest, constant, intermittent, micro) of any type and severity (eso, exo, hyper, hypo, cyclo deviation)

-

3.

Ocular motility disorders (OMDs) of any type and severity (nystagmus, horizontal/vertical gaze palsy, cranial nerve palsy, convergence/divergence disorder, patterns of horizontal incomitance, mechanical restrictions, myogenic disorders like thyroid eye disease and myasthenia with ocular involvement).

We included all three target conditions in recognition of the considerable overlap between them, for example amblyopia and strabismus often coexist with presentation in childhood with frequent persistence to adult life; whilst strabismus and ocular motility disorders often coexist with onset at any age through childhood and adult life.

Interventions

We included any intervention that aimed to improve the conditions of amblyopia, strabismus and ocular motility disorders or alleviate their associated visual symptoms. Interventions may include prisms, occlusion, optical penalisation, glasses, exercises, behavioural vision training, extraocular muscle surgery, extraocular muscle injection of botulinum toxin, pharmacology therapy, and watchful waiting/observation.

Comparisons

We included any comparison between the effectiveness of a treatment modality with another or with no treatment for each condition.

Outcome measures

We included any reported outcome measure that was recorded using any possible instrument or method at any point of time from the intervention.

Types of studies

The following types of studies were considered to be included in this review:

• Cochrane systematic reviews

• Systematic reviews (with or without meta-analysis) inclusive of diagnostic test accuracy reviews

• Randomised controlled trials (RCT)

• Controlled clinical trials (CCT)

• Cohort studies

• Case series with > 10 subjects

We excluded all case reports and letters/editorials.

Search methods for identification of studies

We used systematic strategies to search key electronic databases. We searched Cochrane registers and electronic bibliographic databases including CENTRAL, ovid MEDLINE, SCOPUS, CINAHL, AMED and PsycINFO with search dates of 1st January 2011 through to 27th of September 2016. This period was selected given the considerable increase in studies, trials and reviews in recent years and to extract treatment outcome measures that are relevant to recent research and clinical practice. As per COMET handbook guidance [7] we recognised that overly large reviews would be resource intensive and might not yield important additional outcomes.

We did not search for unpublished studies or in clinical trials registries and we did not hand-search any additional resources. We performed citation tracking using Web of Science Cited Reference Search for all included studies and searched the reference lists of included trials and review articles. Studies identified from the combined search were exported to an EndNoteX7 library. Search terms included a comprehensive range of MeSH terms and alternatives.

SJ and senior author FR developed the table of search terms jointly to include all target conditions and all synonyms of outcome measures, outcomes or assessments. Appropriate Boolean operators were obtained using University of Liverpool library online resources. Whenever available, the filters of “limit to humans” and “exclude case reports” were applied to the search in the databases. An example for search terms for one database is outlined in Additional file 2: Table S2. There was no language restriction while carrying out the search. The search strategy was discussed with and approved by the study steering committee.

Selection of studies

During the first stage of selection, SJ screened the titles and abstracts identified from the search that had been exported to an EndNoteX7 database. Senior researchers (FR and JJK) were consulted when there was a doubt about any abstract. Full text papers were accessed for all papers whose title and/or abstract met the eligibility criteria. These full text papers of potentially relevant studies were considered in the second stage of selection in which the selection criteria were again applied to the full paper content. We resolved disagreements by discussion.

The study protocol was registered in the COMET initiative website. We planned to include systematic reviews, controlled trials, non-systematic reviews, prospective and retrospective cohort studies as well as case series with > 10 subjects at the time of writing the protocol for this systematic review. However this was not done in the actual review (protocol deviation) due to the excessive number of studies that met the inclusion criteria from the higher quality papers of systematic reviews and RCTs/CCTs for most conditions (Fig. 1).

Only a sample of non-systematic reviews and cohort studies was used (as the next best evidence quality to RCTs/SRs) to supplement this review when the number of studies from RCT/SRs for a particular sub-condition was sparse. We performed this also to check for any potentially important missed outcome measures from RCTs/SRs, e.g. long-term outcome measures or adverse events. The sample was variable depending on the availability of articles within the search results pertaining to a certain condition. The sample was increased until outcome measure saturation was achieved, defined as when no additional new measures could be identified and they were repetitive across studies. One non-systematic review and four retrospective studies for the ocular motility disorder sub-condition “pattern deviation” were included as we could not identify any relevant RCTs/SRs from the search results.

Data extraction

SJ extracted the data using a pre-determined data extraction form. Senior reviewer FR reviewed 20% of studies to confirm fulfilling data extraction. There were no disagreements or inconsistencies.

The following data was extracted from each study:

-

Demographics

-

1.

Study type.

-

2.

Author details.

-

3.

Year and journal of publication.

-

4.

Country where study was conducted.

-

5.

Condition(s) under investigation (amblyopia/strabismus/ocular motility disorder).

-

6.

Age of participants in the study population.

-

1.

-

Outcome measures

-

1.

The designated outcome measure (primary and secondary).

-

2.

Outcome measurements (methods or instruments of measurements).

-

3.

The time points at which they were measured.

-

1.

Data analysis and presentation

All data was extracted verbatim from the source manuscripts to facilitate external critical review of the COS right back to its inception. Different nomenclature or aspects used to indicate the same outcome measure were grouped within main outcome headings (domains) when applicable to facilitate easy classification of outcome measures. For example for amblyopia the following aspects were recorded under the outcome measure heading of visual acuity (VA): best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), near visual acuity and binocular visual acuity. They were all recorded as reported in individual studies and then grouped together under one main outcome measure (VA). The method of measurement for BCVA was reported; e.g. using “Electronic Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) VA protocol” or “Snellen chart” etc. and in addition we recorded the time when the measurement was made.

A similar classification and tabulation of information regarding the different outcome measures for the different conditions and sub-conditions was used. For the purpose of this study we did not perform a quality assessment for outcome data from the included studies as we sought only to create an item bank of all utilised outcome measures and outcome measurements. Hence a critique of the methodological quality of the studies was not necessary [7].

We generated an item bank of relevant outcome measures for amblyopia, strabismus and ocular motility disorders presented in percentages of frequency in included studies. In addition we produced an inventory of methods of measurements and their timings. Ocular motility disorders outcome measures were further stratified by sub-condition.

Results

Study selection

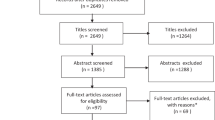

Electronic search of the six databases returned 22,217 hits, which were exported to the reference manager “EndNote X7”. Titles were screened and the number reduced after removing duplicates and non-relevant papers to 2982 reports (Fig. 2). Another 1260 papers were excluded after screening the abstracts.

We were left with 1722 potentially relevant reports to our review question and meeting our eligibility criteria in review protocol (systematic reviews, controlled trials, cohort studies, and case series with > 10 patients for target conditions and populations). Due to the large number of the potently eligible papers, we considered a modification to our eligibility criteria stated previously in the study protocol. We consulted the COMET handbook in which it is suggested, as an option, to perform the systematic review in stages to check if outcome saturation is reached [7] We took a decision, as a first stage analysis (protocol deviation, Fig. 1), to include only systematic reviews and controlled trials initially. This presented us with a total of 165 studies. Out of those, 53 studies were excluded after reading full articles due to irrelevance or lack of “visual or ocular motility” outcomes leaving us with 112 eligible systematic reviews and trials.

Then, when no systematic reviews or trials were found to cover a particular sub condition, cohort studies were considered as the next stage of the analysis. Moreover, we included additional non-systematic reviews distributed across the different conditions and sub conditions of motility disorders to ensure a comprehensive literature review and data saturation. The included number of both cohort studies and non-systematic reviews was 30 in total (4 cohort and 26 non-systematic reviews).

The total number of studies included in analysis in this review eventually was 142 unique studies. The studies came from a wide range of countries with predominance from the United States, the United Kingdom, China and various European countries (Fig. 3).

The following sections will present our findings individually for each of the three conditions: Amblyopia, Strabismus and OMDs outlining types of included studies, types of the conditions, age groups and treatments and listing outcome measures, measurements and commenting on timings. Further subgroup analysis is carried out for OMDs sub-conditions.

Amblyopia

Types of included studies

In this review we looked at a total of 42 studies in amblyopia including six Cochrane reviews, eight systematic reviews and meta-analysis, 24 controlled trials and four non-systematic reviews.

Types of amblyopia and included age groups

The types of amblyopia targeted in included studies ranged from childhood amblyopia [1, 11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] to residual amblyopia in older children [43, 44], adolescents or adults [40, 41, 45, 46], unilateral [3, 12] and bilateral [3], refractive [3], anisometropic [19, 23], strabismic [24, 47], and stimulus deprivation amblyopia [48].

Types of treatment

Interventions varied from the “gold standard” refractive correction and occlusion or atropine penalization [24, 27, 30, 31] to the more modern controversial treatments such as low-level laser [46], photic stimulation [43], and medical and behavioural treatment [45] which were more likely to be used beyond the visual maturation age when conventional treatments often fail.

Occlusion dosages and approaches were investigated in a number of included studies such as part-time versus full time occlusion [38], personalized versus standardized [33], and occlusion versus Bangerter filters [23]. Atropine penalization versus patching, and atropine combined with plano lenses were investigated in three of the included studies [20, 31, 34].

Binocular training with interactive computerized games or video clips versus monocular occlusion treatment were under investigation in seven studies [12, 22, 25, 28, 35, 36, 40]. Levodopa was the main treatment used in two studies [16, 44] and Citocolin combined with patching was used to treat residual amblyopia in older children in one of the included studies [29]. Acupuncture and Chinese medicine were the main therapeutic intervention for amblyopia in six of the included [11, 18, 19, 21, 32, 49].

Outcome measure domains

We identified ten domains of outcome measures in these studies (Table 1): “visual acuity” (86%), “stereopsis or sensory outcomes” (40%), “adverse events” (33%), “health-related quality of life” (HRQoL) (21%), “compliance” (19%), “refractive outcomes” (12%), “ocular alignment” (10%), “economic data” (7%), “visual evoked potential” (VEP) (5%), and “detection by photoscreeners” (2%).

Outcome measure subdomains and measurements

Visual acuity

The majority of studies (86%) measured visual acuity (VA) as the primary outcome measure. Variable descriptions used included improvement in VA [11, 18, 25, 28, 32, 35, 39, 45, 47], mean VA [3, 12, 13, 23, 40, 44, 48], median change in VA [23, 24], and “an increase of two or more lines of visual acuity or a final visual acuity of 20/25 or better” [20]. We identified a minority of subdomains of the outcome VA being reported by single studies such as near VA to compare it to distance visual acuity prior to amblyopia treatment [17] and “binocular VA” [39].

The LogMAR unit was universally used by all studies to report VA (n = 38) however different charts and distances were used depending on varying factors such as participant’s age or setting. Relative to studies that specified which charts were used, the most commonly reported tests were “Isolated Crowded Amblyopia Treatment Study HOTV for subjects aged 3 to < 7 years” [14, 17, 27, 34, 39, 44, 45] and “Electronic Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study VA protocol for subjects aged 7 or older” [14, 27, 34, 44, 45]. “Snellen chart” was reported as an alternative by a lesser number of studies [14, 16, 39, 45] and “Crowded Acuity Test” was used in two studies [30, 43].

Stereopsis/sensory outcomes

These were reported in 17/42 (40%) of the studies. In one study “stereo-sensitivity” was reported rather than stereopsis, in order to be able to represent nil stereoacuity by zero, which therefore can facilitate quantitative analysis as suggested by Tsirlin et al. [45].

Seven out of 17 of the studies did not report a particular outcome measurement, however the unit was given as “seconds of arc” in six studies [11, 12, 20, 23, 28, 42]. To measure near stereoacuity, “Randot Preschool test” was reported in four studies [27, 31, 34, 45], “Frisby test” in two [26, 45], and “Lang stereo test II” in two studies [23, 24]. “Bagolini glasses at distance & near” was used in addition, to determine lower levels of binocularity in the same previous two studies by Agervi et al. [23, 24].

Adverse events

The reported variants of this outcome measure included “diplopia” [12, 35, 47, 48], “occlusion amblyopia” [12, 47], “visual disorientation” [47], “skin irritation” [15], and “allergy to patches” [47, 48]. Adverse events were assessed using “a survey containing 17 items with a Likert scale completed by child and parent” in the RCT of Levodopa in older children by the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group (PEDIG) [44]. The remaining studies did not give a particular method to gather this outcome measure.

HRQoL

This is increasingly being reported as an outcome measure in the treatment of amblyopia. The studies reported more than ten different instruments. The most commonly reported questionnaire in these was “The Amblyopia Treatment Index (ATI)” [37, 41, 50, 51].

Compliance

This was assessed using “objective occlusion dose monitoring” in three studies [12, 30, 37], by discussions with the parent [34], or review of a calendar log maintained by the participant and parent [44].

Ocular alignment

Interestingly ocular alignment was not reported as an outcome measure in the majority of the included studies (88%), even for strabismic amblyopia. However, it was highlighted in the PEDIG trials where it was measured using a “simultaneous prism and cover test” [27, 31, 34, 44] and in one Cochrane review where it was measured using “cover test” [42].

Refractive outcomes

“Median spherical equivalent” [14, 23, 24] and “spherical and cylindrical refraction” [13] have been reported in included studies.

Visual evoked potential (VEP)

VEP was reported as a secondary outcome in addition to visual acuity in the study conducted by Ivandic et al. after the use of low laser for adolescents and adults with amblyopia [46]. “Multifocal visual evoked potentials (M-VEP) amplitude and latency” was measured in a number of the subjects in the trial. Another example of using “VEP latency” as an outcome measure was reported by Yang et al. in a meta-analysis looking at studies that used Levodopa in the treatment of amblyopia in children < 18 years of age [16].

Timing of measurements

We found variable timings that ranged from six weeks (post binocular training) [35, 40] to three years (post strabismus surgery in amblyopia [42], and post auricular point sticking therapy [18]. However 10 weeks [25, 27, 34], 6 months [11, 32, 40] and 12 months [3, 12, 29, 47, 48] were the commonest timings given. Long-term outcomes were measured at 15 years of age in the RCT of “Atropine vs patching for treatment of moderate amblyopia” by the PEDIG [31] and at seven years of age in the review of “Occlusion for stimulus deprivation amblyopia” [48].

Strabismus

Types of included studies

We included 33 strabismus studies distributed as nine Cochrane reviews, four systematic reviews,13 controlled trials, and seven non-systematic reviews.

Types of strabismus and included age groups

This review included outcome measures extracted from studies investigating a wide range of strabismus types in different age groups.

While strabismus in general was under evaluation in around one third of the included studies (33%), intermittent exotropia by itself was the focus in more than one third (36%). This might be a reflection of the fact that intermittent exotropia is a common form of childhood exotropia [52]. Moreover, it is well established that it is one of the commonest worldwide constituting around 25% of all strabismus types [5].

On the other hand, esotropia was the target condition in only five studies (15%) with “Infantile esotropia” being the type in four of them [53,54,55,56] and “High AC/A ratio esotropia in teenagers” in one [57]. Three vertical strabismus studies were also among studies included in our review; two on dissociated vertical deviation (DVD) management [58, 59] and another on inferior oblique overaction [60].

The majority of subjects targeted in included strabismus studies were from the paediatric age group. In this review more than half of strabismus studies had children less than 18 years of age as participants compared to only 12% for adults [61,62,63,64]. The remaining studies were either generalised for adults and children [2, 4, 5, 58, 60, 65,66,67,68] or did not state a specific age group [52, 59, 69].

Types of treatment

Over half of the studies (52%) discussed outcome measures following surgical interventions for strabismus, most commonly muscle surgery (45%) [5, 42, 55, 56, 60, 61, 64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72] and less for botulinum toxin injection [2, 54]. Muscle surgery and botulinum toxin injection were both combined in one study [63]. In contrast, non-surgical or conservative treatments were evaluated in five of included studies (15%) [52, 57, 73,74,75]. Another 15% of studies involved both surgical and non-surgical interventions and reported treatment outcome measures following either method [4, 53, 58, 59, 76].

Outcome measure domains

We identified 14 domains of outcome measures for strabismus (Table 2). The four most commonly reported ones were “motor alignment” (79%), “binocularity” (64%), “adverse events” (61%), and “health-related quality of life” (48%). The less commonly reported outcome measures included “visual acuity” (24%), “control of deviation” (24%), “fusional vergence” (15%), “ocular movements” (9%) and “AC/A ratio” (3%).

Outcome measure subdomains and measurements

Motor alignment/angle of deviation

This was reported as “motor alignment” or “angle of deviation” in 26/33 studies. This was further described to be measured “at near and distance” in seven studies out of these [4, 5, 63, 66, 70, 71, 77].

In 12 studies alignment was measured using “prism alternate cover test PACT” [4, 5, 54, 58, 59, 63, 67, 70, 71, 74, 77, 78] and /or with “simultaneous prism cover test SPCT” in eight studies [4, 53, 63, 66, 74, 75, 77, 79]. “Cover test” was reported in five studies [2, 42, 73, 74, 79], “Synoptophore” in four [2, 4, 42, 53] and “Hirschberg test” in three [54, 73, 79]. Krimsky test was reported as an alternative test in subjects with poor cooperation in one study [54], when cover tests are not applicable [63] or in cases with poor vision (worse than 20/200) in one RCT [60].

It is noteworthy that there is still no total agreement on the definition of a successful ocular alignment [5], varying from 5 to 8 to 10 PD from orthophoria. However there was a considerable agreement on defining success in included studies as orthophoria within 10 PD [2, 42, 53, 61, 65, 74, 80].

Stereopsis/sensory outcomes

Sensory outcomes were either reported as any level of “binocularity/stereopsis” [2, 52, 55, 57,58,59, 67], or as “stereoacuity” (near or presumably near) [5, 56, 60, 71, 73, 76, 77, 79], or both; with “binocularity” and “stereoacuity” stated as two distinct outcome measures [42]. Additionally, “steroacuity at near and distance” was measured in four of intermittent exotropia studies [4, 66, 68, 74].

The outcome measurement used to assess stereoacuity were similar to those found in amblyopia studies, “Randot stereoacuity test” [71, 73, 74], with the addition of Titmus Housefly [42, 55, 60] and TNO [52, 66, 67]. “Sensory fusion” was measured with “Worth’s 4 dots” test in two studies [42, 67]. In one review, a stepwise approach of assessing binocularity was undertaken. After “stereoacuity” (the gold standard), “simultaneous perception” and “motor fusion” were considered next [53].

Adverse events

These included postoperative alignment complications such as “induced A or V pattern” [60, 70], “induced vertical deviation” [2, 54] “development of DVD” [56, 60], “induced incomitance” [69, 71], or visual complications such as intolerable diplopia [2, 65] and “development of amblyopia” [4, 53].

Other adverse events specified in included studies were “globe perforation” [65, 70, 78], and “induced ptosis” post botulinum toxin injection [2, 53, 54].

Long-term change following surgical procedures including “recurrence of deviation” [68], “overcorrection” [4, 78] and “re-operation rate/number of operations needed” [53, 55, 65, 78] were reported.

HRQoL

This was assessed using different questionnaires that could be generic (for example SF-36) [61, 62], or specific to age (for example EYE-Q) [77, 78], specific to vision (for example VFQ-25) [58] or specific to condition (for example the IXTQ) [5, 50, 51, 62, 72, 77].

Strabismus and amblyopia were often combined in the same HRQoL questionnaire (for example the A&SQ) [50, 61, 62, 64].

Visual acuity

Only 24% of included strabismus studies reported BCVA as an outcome measure. LogMAR or LogMAR equivalent was the most reported unit used [42, 52, 63, 79].

Control of deviation

This outcome measure was reported in seven intermittent exotropia studies [5, 52, 68, 74, 76,77,78]. Different scores were used including “Newcastle Control Score” [5, 52, 68, 77, 78], “Office Control Score” [5, 74], “Mayo Score” [77, 78] and “Petrunak and Rao’s five point scale” [52]. “Control to show whether the deviation is latent or manifest” was also considered for DVD in the review by Christoff et al. [59].

Fusional vergence

A further outcome was referred to as “fusional vergence for distance and near” in three [2, 66, 68] or as “motor fusion at distance or near or both” in two studies [4, 42]. It was measured in one included study using a “base out or base in prism test/synoptophore” [42] or “a prism bar” [66].

Ocular movements

These were included in vertical strabismus such as DVD [59] and inferior oblique overaction [60]. Muscle action was documented on a grading scale from 1 to 4 [59] or 0–4 [60].

AC/a ratio

AC/A ratio was reported as an outcome in a review by Piano et al. for the conservative treatment of intermittent distance exotropia [52].

Timing of measurements

The time of measurement varied between studies and did not clearly correlate with the intervention. The measurement was often done at multiple time points [54, 61, 63, 66, 67, 70, 78] or at one time point otherwise. It ranged from one week [66] to three years [42, 73]. The most frequently given timings were 3 months [54, 60, 61, 63, 66, 69, 70, 72, 78], 6 months [2, 53, 54, 61, 63, 65,66,67, 70, 71, 74,75,76, 78] and one year [58, 61, 63, 64, 67]. Long-term outcomes were measured at age of six years in one study for infantile esotropia [55].

Ocular motility disorders (OMDs)

Types of included studies

A total of 68 studies were included for ocular motility disorders (OMDs), distributed as eight Cochrane reviews, 12 systematic reviews, 29 controlled trials, 15 non-systematic reviews and four retrospective studies.

Types of ocular motility disorders and included age groups

We classified OMDs into seven sub-conditions. Table 3 gives an outline of the common outcome measures across these sub-conditions in included studies.

Forty five per cent of included OMDs studies [81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116] had adults exclusively as subjects due to the nature of conditions under evaluation such as thyroid eye disease and neurological diseases with gaze palsies, which exist in adults typically. In contrast, less than tenth of the studies were done on paediatric subjects [117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124]. Some of these were for conditions found predominantly in teenagers such as convergence insufficiency and accommodation dysfunction and others included disorders with an early onset such as infantile nystagmus and pattern deviations. The remaining studies had mixed adults and children populations (n = 18/67) [80, 125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141] or the age was not clear (n = 6/67) [142,143,144,145,146,147].

Types of treatment

Interventions used in these studies included medical, surgical and conservative measures.

Outcome measure domains

We identified ten domains of outcome measures common for the majority of OMDs (Table 4). The most frequently reported outcome measures were “range of eye movement” (34%), “HRQoL” (28%), “improvement in diplopia” (26%), “visual acuity” (22%) and “motor alignment” (21%). Other less frequent outcome measures included “adverse events” (15%), “improvement in symptoms” (13%), “improvement in AHP” (10%), “increasing field of BSV” (6%) and “stereoacuity” (6%).

Outcome measure subdomains and measurements

Range of eye movement

This was the commonest outcome measure reported in general for OMDs and was included in all sub-conditions except for accommodation and convergence disorders. This was either included in composite scores or as a distinct outcome measure. In one RCT the nine positions of gaze were videotaped and measurements were done “directly on photographs drawing a horizontal straight line from internal canthus” [102]. In another study this was described as “in 8 positions of gaze binocularly and monocularly” [132].

HRQoL

HRQoL outcome measures were mostly prominent in thyroid eye disease studies [82, 84, 91, 95,96,97, 104, 107, 109,110,111, 115, 116], nevertheless they were also scattered in other sub-conditions; accommodation and convergence disorders [125], ocular myasthenia [142] and central causes of eye movement disorders [80, 81].

Improvement in diplopia

This was another common outcome measure; however there was incongruity in the position of gaze free from diplopia. Position of gaze was mostly not indicated [90, 93, 101, 105, 112, 115, 116, 127, 133, 141, 144, 146], however improvement was confined to primary gaze in a number of studies [106, 108, 114, 119].

Visual acuity

Only 22% of the included studies reported visual acuity and these were mostly for nystagmus or orbital abnormalities. “Binocular visual acuity” was specifically additionally indicated in two of nystagmus studies [85, 126].

Motor alignment

This was reported in all sub-conditions except nystagmus studies. Whenever reported, this was either assessed with cover/uncover/alternate cover test without quantification [129, 132] or quantified using “PACT” [138, 140] or “Krimsky” [138] in less cooperative patients. Moreover, in addition to horizontal and vertical deviation, torsion was evaluated in a number of pattern deviation studies objectively [121, 136, 139, 140] or less commonly subjectively [121].

Timing of measurements

Multiple time points [82, 92, 94, 96, 97, 100, 101, 103, 115, 118, 121, 128] or spans of follow up were often given [83, 84, 99, 105, 111, 113, 126, 139]. However 6 months [82, 83, 97, 99, 103, 104, 111] and 12 months [82, 97, 98, 103, 107, 113] were frequent timings given in thyroid eye disease studies. Twelve weeks timing was common for accommodation and convergence disorders [117, 118, 125, 128].

More details on included studies for amblyopia, strabismus and ocular motility disorders arranged alongside identified outcome measures, outcome measurements and timings are given in Additional file 3: Table S31, Additional file 4: Table S3.2, Additional file 5:: Table S3.3 and Additional file 6: Tables S4.1–4.7).

Outcome measures per sub-condition

Accommodation and convergence disorders (n = 7) (Additional file 6: Table S4.1)

For this group of disorders, the most prominent outcome measures were “patient symptoms” recorded with “Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey (CISS)” (86%). “Near point of convergence NPC” and “positive fusional vergence” were less common. Alignment measurement was not expansively assessed in included studies apart from measuring “phoria” in two studies [128, 147] or ruling out manifest strabismus with “cover test at distance and near” for inclusion in one trial [124] . “Amplitude of accommodation” [118, 128, 147], and “accommodative facility” [118, 147] were also reported. “Dynamic retinoscopy” was reported by one study [147].

Ocular mechanical restriction (n = 6) (Additional file 6: Table S4.2)

The outcome measures “resolution of diplopia”, “motility assessment” and “alignment” were mutual with other OMDs.

However, in certain circumstances such as in acute orbital floor fractures, the outcome measures “oculocardiac reflex” [119],“visual acuity” [119, 141] and “pupillary function” [119] were important.

“Assessment of fractures and entrapment of soft tissue” was evaluated with radiographic imaging such as helical CT [119].

“Forced duction test” was reported to check muscle restriction and entrapment in two included studies [119, 122]. Other assessments done in orbital fractures included “globe integrity” [119], “globe dystopia” [119, 122] and “infraorbital hyposthaesia” [105, 119, 141]. A further outcome measure related to appearance was “resolution of enophthalmos” [105, 141, 146].

Ocular myogenic disorders (n = 30) (Additional file 6: Table S4.3)

Thyroid eye disease

Treatment response in thyroid eye disease is commonly evaluated using composite scores such as “VISA” [109] and “EUGOGO score” [91, 92, 103]. Modified versions of existing scales are often developed and used (for example “modified EUGOGO” [101], and “modified Werner grading scale” for orbital inflammation [96]). In addition, we found a high frequency of a number of widely recognised scoring systems such as “The clinical activity score (CAS)” to assess disease activity [82, 84, 90, 92, 95, 97,98,99, 101, 103, 104, 108, 110,111,112, 114,115,116] and “NO SPECS” to assess disease severity. [82, 84, 90, 103, 104, 111].

“Subjective diplopia” was frequently assessed using “the Gorman diplopia score” [90, 95, 116]. Ocular muscle motility assessment was mostly involved within composite scores but occasionally measured with dedicated scores (for e.g. The Total Motility score (TMS)) [116]. Additional outcome measures reported by studies for thyroid eye disease included “the need for post treatment corrective procedures” [83, 84, 91, 98, 111], and “orbital volume/orbital fat and muscle volume”. [95, 112].

Ocular myasthenia gravis and progressive external ophthalmoplegia

In addition to the previously stated outcome measures shared with other eye motility disorders such as “improvement in diplopia” [127, 133] and “eye movement measurement” [102], there were outcome measures specific to myasthenia reported by included studies. These included “quantitative ocular myasthenia gravis score (OMG) score” [142] and “progression to generalised myasthenia gravis” [127, 133, 142]. Other associated ocular motility abnormalities reported included “inter-saccadic fatigue”, “gaze-paretic nystagmus”, “fatigue of accommodation” and “reduced velocity of pupillary constriction” [133]. Quality of life was evaluated using “the 15-item Myasthenia Gravis quality of life scale” in one study [142].

Ocular motility disorders secondary to neurogenic disorders (n = 6) (Supp. Table 4.4)

These refer to conditions such as third, fourth and sixth cranial nerve palsies. Clinical outcome measures included here in addition were “palpebral fissure size” [93, 144] and “pupil size” [144] for third nerve palsy. Bi et al. used “The cervical range motion (CROM) score” to quantify diplopia in a pilot RCT on acupuncture for the treatment of oculomotor paralysis [93].

In the review by Engel, in congenital fourth nerve palsy, alignment was checked with “a more sensitive 2-step test” [131]. “Facial asymmetry” was evaluated, and “superior oblique muscle atrophy/absent trochlear nerve” were examined with “high definition MRI” in the same study [131]. “Abnormal head position” was measured objectively using “a goniometer” in degrees [131]. An important adverse event sought after treatment here included “secondary Brown syndrome” [131].

In sixth nerve palsy, motility outcomes were included to reveal any “degree of incomitance” while measuring deviation, and to check for “medial rectus muscle contracture” using “forced duction test” [130]. “Scott’s force generation test” or “electrooculography/electromyography” were used to assess “lateral rectus muscle function” [130].

Nystagmus (n = 8) (Additional file 6: Table S4.5)

Outcome measures that were shared with most of the remaining OMDs were “visual acuity” (75%) [85,86,87, 120, 126, 145], “improved head posture” (25%) [120, 126], “patient satisfaction” (25%) [87, 126] and “range of eye movement” (13%) [132]. However, it is important to note that vision in patients with nystagmus was assessed more comprehensively with additional specifications in a few studies; “binocular visual acuity” was reported in two studies [85, 126], “gaze-dependant visual acuity GDVA” in one study [86], “near visual acuity” in one study [87] and “estimated visual acuity using pattern reversal VEP” in one study for infantile nystagmus [126].

“Eye movement recordings” was included in six nystagmus studies (75%) [85,86,87, 126, 132, 145]. Examples of the methods used to record eye movement included “3-D video-oculography” [87] and “an infrared video pupil tracker” [86]. Different specific characteristics of nystagmus were gathered from eye movement recordings including “foveation/recognition time” [126, 137], “broadening the null point” [137, 145], and “nystagmus waveform” [126, 145]. The specific symptom of “oscillopsia” was assessed in two included studies [120, 137].

Pattern deviation (n = 5) (Additional file 6: Table S4.6)

A special feature with this group of conditions was the torsion deviation measurement reported in 80% (n = 4/5) of studies [121, 136, 139, 140]. “Objective torsion” using “indirect ophthalmoscopy” was more commonly reported [121, 136, 139, 140] than “subjective torsion using double Maddox rod test” [121]. An example of a grading scale used was “-4 underaction to +4 overaction with 0 being normal” [121].

Ocular motility disorders secondary to central causes (n = 7) (Additional file 6: Table S4.7)

These include gaze palsies and some forms of acquired nystagmus. In addition to the common outcome measures with other sub-conditions, there were others highlighted in a number of included studies. These comprised particular attention to “saccades and pursuits”. Measurements were done using “the optokinetic drum” or “video-oculogarphy” [132]. “Near point of convergence” was reported in one study [106].

Discussion

Systematic reviews investigating various specialities including ophthalmology [148,149,150,151] are increasingly being performed. What is evident from many systematic reviews is that the results from included trials and studies cannot be meta-analysed because of the variation in outcome measures used across the studies. The COMET initiative calls for development of COS in order to provide a minimum set of outcome measures which will facilitate future synthesis of results. To our knowledge this is the first review using systematic methods in accordance with the COMET handbook aiming to develop an item bank of outcome measures in the treatment of amblyopia, strabismus and ocular motility disorders.

We chose to combine these conditions in one report due to the great overlap between them and their frequent co-existence in subjects. Indeed some might consider strabismus as a subset of ocular motility disorders and vice versa. For example esotropia from sixth cranial nerve palsy was classified under motility disorders while others may classify it under strabismus. Additionally, strabismus can cause or result from amblyopia, and similarly with ocular motility disorders with childhood onset. Therefore it is meaningful to consider them all in one generalised report.

Although we did not cover every type, this review includes outcome measures extracted from studies investigating a wide range of amblyopia, strabismus and ocular motility disorders in different age groups undergoing nearly all possible methods of interventions.

Amblyopia

Although we attempted to include all types of amblyopia in this paper, we found that the majority of the studied variants were anisometropic, strabismic and combined anisometropic and strabismic amblyopia. Even though aetiologies were different, therapeutic interventions and outcome measures were comparable.

This review found that VA is the only outcome measure agreed by the great majority of included amblyopia studies. Stereopsis, adverse events and HRQoL were also relatively common however they were reported by less than half of the studies. VA and stereopsis measurement methods largely depended on the age of subjects who were mostly from the paediatric age group.

BCVA is measured typically in children from around the age of 3–4 years as well as in adults. It is the most commonly used outcome to assess visual acuity in our review and in perhaps in general for any eye condition. However, it is increasingly recognised that it does not truly reflect visual function needed in normal daily activities [151]. Additional assessments that can give more information about visual function include contrast sensitivity, near visual acuity, reading speed and visual field sensitivity [151].

It is not uncommon to find older children and adults with residual amblyopia, and as a result various non-conventional therapies attempted to treat it beyond the plasticity period. When that is done visual function can be assessed using conventional methods in addition to more objective and sensitive methods especially in the research environment. VEP is one outcome measure used to assess visual function post treatment in older children and adults. It is recommended to use VEP latency rather than amplitude due to its higher sensitivity [46].

Due to the strong association between amblyopia and strabismus, we made the assumption that ocular alignment would be a standard outcome measure in amblyopia studies, which was not the case once results had been gathered and analysed. Only 12% of the studies included this outcome measure.

Regarding health-related quality of life, it is notable that treatment side effects and compliance are occasionally evaluated and reported within HRQoL questionnaires, i.e. collecting all subjective or patient-reported outcomes in one type of a composite score. Therefore a number of amblyopia studies that reported HRQoL did not consider adverse events or compliance as independent outcome measures.

The timing of reported measurements was variable between studies however the most frequent time point found here was 12 months.

Strabismus

There is nearly a total agreement on the necessity to measure motor alignment at distance and near using prism alternate cover test (PACT) or simultaneous prism cover test (SPCT) in ideal situations; and Krimsky in poor cooperation or low vision [60]. The difference between PACT and SPCT is that the first measures the alignment by covering each eye alternatively whereas the second measures alignment before binocular vision is disrupted. Generally the total misalignment measured by PACT is the most often one reported [77].

The other outcome measures reported by more than half of strabismus studies were “binocularity (stereopsis/BSV)” and “adverse events”. “HRQoL” was reported by just under half of included studies.

Binocularity was mostly measured in included studies using near stereopsis. We found that distance stereopsis is not typically assessed with the exception of intermittent exotropia. A moderate correlation was found between near and distance stereoacuity in previous studies [66] and most clinicians prefer to measure near stereoacuity over distance stereoacuity because of better patient cooperation [5]. On the other hand, some authors suggest that distance stereoacuity is a better indicator for intermittent exotropia progression [66]. For example, in the RCT conducted by Saxena et al., distance stereoacuity showed continued improvement for up to three months post treatment compared to one week for near stereoacuity [66].

HRQoL is a complex concept with wide variation in how people perceive it individually and within one individual over time [62]. There is no agreed definition of QoL [51] however it can be considered a reflection of one’s overall well-being and life experience, which is affected by different factors including physical, psychosocial and environmental elements [62]. McBain et al. found that adults with strabismus can have one of two types of QoL concerns; for example there may be functional concerns for those with diplopia and psychosocial concerns for those with strabismus but no diplopia [62]. It must be highlighted that the aim of measuring HRQoL outcome is to provide appropriate support depending on specific concerns or needs. It seems nevertheless that there is still no total consensus on one method of measurement of HRQoL in strabismus and amblyopia and that there is room for further development to reach agreement.

In comparison to the agreement on the above measures, there was dissimilarity in measuring other outcome measures such as “visual acuity” and “control of deviation” for patients with strabismus.

This review found only one third of strabismus studies considering “visual acuity” important to measure after treatment. This could be partially explained by the fact that it is relevant mostly in children to check the status of amblyopia and that vision is not a primary concern when there is prior amblyopia in adults undergoing for example surgical correction.

Furthermore, there are a number of outcome measures relevant only in specific variants of strabismus for example “control of deviation” and “AC/A ratio”. Control of deviation is pertinent mostly in cases of intermittent exotropia and DVD. AC/A ratio is important mostly in high AC/A esotropia.

“AC/A ratio” is often measured for intermittent exotropia as well. It was shown previously by some authors that lower AC/A ratios were attained post extensive orthoptic exercises for intermittent distance exotropia [52]. However, due to technical difficulties in measurements and potential inaccuracies if occlusion is not used while measuring it to differentiate between true and pseudo divergence excess, it is challenging to use it as a standard test to guide treatment [52].

Six months was the most commonly given timing to report outcome measures post strabismus treatment although there was great variation between studies.

Ocular motility disorders

Agreement on outcome measures for OMDs was the least compared to amblyopia and strabismus probably due to the wider variation in clinical features and therefore we provided outcome measures per sub-condition. However we found a degree of overlap in some outcome measures between the seven categories such as “range of eye movement”, “HRQoL” and “improvement in diplopia”.

Generally, it seems that having a satisfactory “range of eye movement” was the preferred outcome measure in eye motility disorders and that measurement in both ductions and versions is recommended to differentiate restrictive from paralytic eye conditions.

“HRQoL” assessment was shown to be especially relevant in disfiguring conditions such as thyroid eye disease. The reason behind that is the previously noted psychological factors which do not correlate well with objective clinical measures for unclear reasons [107]. There have been various versions of Graves’s ophthalmopathy QoL questionnaires, but once more there is no consensus regarding their use [109]. A common feature in such questionnaires however is addressing both visual and appearance-related aspects of QoL [97, 107, 110]. Some authors considered in addition evaluating long-term quality of life in this group of patients for up to 11 years [107].

Furthermore, for OMDs complicated with “diplopia”, a primary outcome measure frequently emphasised here was to assess improvement or resolution of diplopia. However, it would be useful, we suggest, to have an agreement whether any improvement in diplopia would be acceptable or improvement in diplopia in primary gaze, down gaze, with or without prisms would be required to define success. Also whether subjective reports are sufficient or they need to be combined with objective measurement of “field of binocular single vision”. Similarly for measurement of deviation or reporting “alignment”, an indication whether orthophoria in primary gaze or in more positions of gaze to be planned or achieved would be more helpful.

“Improvement in head posture” was found often closely related to improvement in diplopia and alignment, however this review has shown that it was not consistently addressed in relevant studies. Reporting head posture improvement in relation to the null position was similarly incongruous in nystagmus studies.

On the other hand, when diplopia was not the only concern in the ocular motility disorder as in accommodation and convergence disorders, “improvement in symptoms” would be reported. “The Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey” appeared to be widely accepted for this purpose [117, 123, 125, 128, 147].

Although assessment of “visual acuity” is typically standard in eye conditions, it was not reported in 75% of included OMDs studies. As noted above, its measurement was shown to be vital in nystagmus patients mostly. However, consensus is needed about what category of visual acuity to measure. Vision assessment was also relevant in thyroid eye disease and orbital fracture for optic nerve function assessment in relation to orbital changes.

Timing of reported outcome measures here was variable due to various factors indicated above.

Study strengths and limitations

The strength of this work is that the review followed a prescribed process for the creation of an item bank of outcome measures [7]. The resultant item bank is a comprehensive list that underpins the first stage of the process to develop Core Outcome Sets for amblyopia, strabismus and ocular motility disorders.

On the other hand, despite some overlap between target conditions, the varied review scope and inclusion of a wide range of conditions together could be considered a limitation preventing us from finding all the relevant reported outcome measures for every target condition and sub-condition. Although generalised and overlapping outcome measures for amblyopia, strabismus and ocular motility disorders were extracted here, specific and more refined categories of outcome measures might have been overlooked.

Another potential limitation is the exclusion of other studies of lower quality than systematic reviews and controlled trials, which might have resulted in missing valuable sources of reported outcome measures in literature. It would not be possible however to include all types of studies for a wide group of conditions as in our review. This might be feasible for conditions/sub-conditions when investigated individually.

Future work and recommendations

We next plan to conduct an iterative consensus process (Delphi surveys and group meetings) with key stakeholders including patients, clinicians and researchers as the second stage of developing these COSs. This stage will be to standardise what to measure, i.e. outcome measures. Subsequent work will be required to standardise how to measure them, i.e. outcome measurements and later, when to measure them, i.e. timing of measurements.

In terms of developing “Core Outcome Sets”, we suggest the inclusion of both subjective and objective outcome measures; and both positive (i.e. improvement from baseline) and serious negative outcomes (i.e. adverse events). Furthermore, choosing feasible and easily available assessments is important. We also recommend that “long-term outcomes”, especially for known chronic conditions, are considered.

Conclusions

We generated lists of the most reported outcome measures for amblyopia, strabismus and ocular motility disorders within included studies with indications to specific outcome measures in certain sub-conditions. We also identified the most reported outcome measurements and their timings from intervention to some extent.

This review also demonstrates significant variation in outcome measure reporting within published studies in the three conditions confirming the challenge in efficient comparison, combination and synthesis of data.

Various factors might be responsible for inconsistency between studies in reported outcome measures in conditions targeted in this review including age group, type of condition and often researcher or clinician preferences. While some of these factors are understandably fixed, researchers and clinicians preferences can probably be unified and standardised.

Although common outcome measures and measurements from the literature are highlighted in this review, this does not imply that they are necessarily the most appropriate outcome measures to be used as “core outcome measures” in trials or clinical practice. Consensus among all stakeholders including patients, clinicians, and researchers is required to establish COS. International agreement would be ideal to maximise usefulness of research overall.

Change history

11 March 2019

.

Abbreviations

- A&SQ:

-

Amblyopia and Strabismus Questionnaire

- AC/A ratio:

-

Accommodative convergence/Accommodation ratio

- AHP:

-

Abnormal Head Posture

- BCVA:

-

Best Corrected Visual Acuity

- BSV:

-

Binocular Singe Vision

- CAS:

-

Clinical Activity Score

- CCT:

-

Controlled clinical trials

- CISS:

-

Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey

- COMET:

-

Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials

- COS:

-

Core Outcome Set

- CROM:

-

Cervical Range Of Motion

- CT:

-

Computerised Tomography

- DHD:

-

Dissociated Horizontal Deviation

- DVD:

-

Dissociated Vertical Deviation

- ETDRS:

-

Electronic Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study

- EUGOGO score:

-

EUropean Group On Graves’ Orbitopathy

- GDVA:

-

Gaze-dependent Visual Acuity

- GO-QoL:

-

Graves Ophthalmopathy Quality of Life

- HRQoL:

-

Health-Related Quality of Life

- IXTQ:

-

Intermittent Exotropia Questionnaire

- Log MAR:

-

Logarithm of the Minimum Angle of Resolution

- M-VEP:

-

Multifocal Visual Evoked Potentials

- NO SPECS:

-

No Signs or symptoms, Only signs, Soft tissue involvement, Proptosis, Extraocular muscle involvement, Corneal involvement, Sight loss

- OMDs:

-

Ocular motility disorders

- OMG:

-

Ocular Myasthenia Gravis

- PACT:

-

Prism Alternate Cover Test

- PD:

-

Prism Dioptre

- PEDIG:

-

Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group

- PROMS:

-

Patient-reported outcome measures

- RCT:

-

Randomised Controlled Trials

- SPCT:

-

Simultaneous Prism Cover Test

- TED:

-

Thyroid Eye Disease

- TES:

-

Total Eye Score

- TMS:

-

Total Motility Score

- TNO:

-

The Netherland Organisation

- UDVA:

-

Uncorrected Distance VA

- VISA:

-

Vision, Inflammation, Strabismus/restriction, and Appearance/exposure

References

Sanchez I, Ortiz-Toquero S, Martin R, De Juan V. Advantages, limitations, and diagnostic accuracy of photoscreeners in early detection of amblyopia: a review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:1365–73.

Rowe FJ, Noonan CP: Botulinum toxin for the treatment of strabismus. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012.

Taylor K, Powell C, Hatt SR, Stewart C: Interventions for unilateral and bilateral refractive amblyopia. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012.

Hatt SR, Gnanaraj L: Interventions for intermittent exotropia. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2013.

Chiu AK, Din N, Ali N. Standardising reported outcomes of surgery for intermittent exotropia--a systematic literature review. Strabismus. 2014;22(1):32–6.

Boers M, Kirwan JR, Wells G, Beaton D, Gossec L, d'Agostino MA, Conaghan PG, Bingham CO, Brooks P, Landewe R et al.: Developing Core Outcome Measurement Sets for Clinical Trials: OMERACT Filter 2.0. In. Great Britain: Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam.; 2014: 745.

Williamson PR, Altman DG, Bagley H, Barnes KL, Blazeby JM, Brookes ST, Clarke M, Gargon E, Gorst S, Harman N, et al. The COMET Handbook: version 1.0. Trials. 2017;18(3):280.

Taylor RH: Guidelines for the management of strabismus in childhood. In. Royal College of Ophthalmology; 2012.

Rowe FJ: Ocular alignment and motility: moving variables in clinical trials. In. Bruges, Belgium. : 34th European Strabismological Association.; 2011: pp. 111–114.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336–41.

Liu M-l, Li L, Leung ping C, Wang Chi C, Liu M, Lan L, Ren Y-l, Liang F-R: acupuncture for amblyopia in children. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2011.

Tailor V, Bossi M, Bunce C, Greenwood JA, Dahlmann-Noor A: Binocular versus standard occlusion or blurring treatment for unilateral amblyopia in children aged three to eight years. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2015.

Alió JL, Wolter NV, Piñero DP, Amparo F, Sari ES, Cankaya C, Laria C. Pediatric refractive surgery and its role in the treatment of amblyopia: meta-analysis of the peer-reviewed literature. J Refract Surg. 2011;27(5):364–74.

Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator G, Holmes JM, Lazar EL, Melia BM, Astle WF, Dagi LR, Donahue SP, Frazier MG, Hertle RW, Repka MX, et al. Effect of age on response to amblyopia treatment in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(11):1451–7.

West S, Williams C. Amblyopia. Clinical Evidence. 2011.

Yang XB, Luo DY, Liao M, Chen BJ, Liu LQ. Efficacy and tolerance of levodopa to treat amblyopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2013;23(1):19–26.

Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator G, Christoff A, Repka MX, Kaminski BM, Holmes JM. Distance versus near visual acuity in amblyopia. J Aapos. 2011;15(4):342–4.

Gong RL. Observation on therapeutic effect of child amblyopia treated with auricular point sticking therapy. Zhongguo Zhenjiu. 2011;31(12):1081–3.

Lam DSC, Zhao JH, Chen LJ, Wang YX, Zheng CR, Lin QE, Rao SK, Fan DSP, Zhang MZ, Leung PC, et al. Adjunctive effect of acupuncture to refractive correction on Anisometropic amblyopia one-year results of a randomized crossover trial. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(8):1501–11.

Medghalchi A, Dalili S. A randomized trial of atropine versus patching for treatment of moderate amblyopia. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2011;13(8):7–9.

Wu L, Zhang GL, Yang YX. Clinical study on electrical plum-blossom needle for treatment of amblyopia in children. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi Zhongguo Zhongxiyi Jiehe Zazhi/Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional & Western Medicine/Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Hui, Zhongguo Zhong Yi Yan Jiu Yuan Zhu Ban. 2011;31(3):342–5.

Bau V, Rose K, Pollack K, Spoerl E, Pillunat LE. Effectivity of an occlusion-supporting PC-based visual training programme by horizontal drifting sinus gratings in children with amblyopia. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 2012;229(10):979–86.

Agervi P, Kugelberg U, Kugelberg M, Zetterström C. Two-year follow-up of a randomized trial of spectacles alone or combined with Bangerter filters for treating anisometropic amblyopia. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91(1):71–7.

Agervi P, Kugelberg U, Kugelberg M, Zetterstrom C. Two-year follow-up of a randomized trial of spectacles plus alternate-day patching to treat strabismic amblyopia. Acta Opthalmologica. 2013;91(7):678–84.

Foss AJ, Gregson RM, MacKeith D, Herbison N, Ash IM, Cobb SV, Eastgate RM, Hepburn T, Vivian A, Moore D, et al. Evaluation and development of a novel binocular treatment (I-BiTTM) system using video clips and interactive games to improve vision in children with amblyopia ('lazy eye'): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials [Electronic Resource]. 2013;14:145.

Stewart CE, Wallace MP, Stephens DA, Fielder AR, Moseley MJ. The effect of amblyopia treatment on stereoacuity. J AAPOS. 2013;17(2):166–73.

Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator G, Wallace DK, Lazar EL, Holmes JM, Repka MX, Cotter SA, Chen AM, Kraker RT, Beck RW, Clarke MP, et al. A randomized trial of increasing patching for amblyopia. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(11):2270–7.

Jafari AR, Shafiee AA, Mirzajani A, Jamali P. CAM visual stimulation with conventional method of occlusion treatment in amblyopia: a randomized clinical trial. Tehran University Med J. 2014;72(1):7–14.

Pawar P, Mumbare S, Patil M, Ramakrishnan S. Effectiveness of the addition of citicoline to patching in the treatment of amblyopia around visual maturity: a randomized controlled trial. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62(2):124–9.

Pradeep A, Proudlock FA, Awan M, Bush G, Collier J, Gottlob I. An educational intervention to improve adherence to high-dosage patching regimen for amblyopia: a randomised controlled trial. Erratum appears in Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(7):865–70.

Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator G, Repka MX, Kraker RT, Holmes JM, Summers AI, Glaser SR, Barnhardt CN, Tien DR. Atropine vs patching for treatment of moderate amblyopia follow-up at 15 years of age of a randomized clinical trial. Jama Ophthalmology. 2014;132(7):799–805.

Han ZH, Qiu M. Randomized controlled clinical trials for treatment of child amblyopia with Otopoint pellet-pressure combined with Chinese medical herbs. Chen Tzu Yen Chiu Acupuncture Res. 2015;40(3):247–50.

Moseley MJ, Wallace MP, Stephens DA, Fielder AR, Smith LC, Stewart CE, Cooperative RS. Personalized versus standardized dosing strategies for the treatment of childhood amblyopia: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials [Electronic Resource]. 2015;16:189.

Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator G, Wallace DK, Lazar EL, Repka MX, Holmes JM, Kraker RT, Hoover DL, Weise KK, Waters AL, Rice ML, et al. A randomized trial of adding a Plano lens to atropine for amblyopia. J Aapos. 2015;19(1):42–8.

Herbison N, MacKeith D, Vivian A, Purdy J, Fakis A, Ash IM, Cobb SV, Eastgate RM, Haworth SM, Gregson RM, et al. Randomised controlled trial of video clips and interactive games to improve vision in children with amblyopia using the I-BiT system. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;1:1-6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307798.

Tang W, Wang X, Tao L. A comparative study on visual acuity and stereopsis outcomes between perceptual learning based on cloud services and conventional therapy for amblyopia. Zhonghua Shiyan Yanke Zazhi/Chinese Journal of Experimental Ophthalmology. 2016;34(5):426–31.

Stewart CE, Moseley MJ, Fielder AR. Amblyopia therapy: an update. Strabismus. 2011;19(3):91–8.

Matta NS, Silbert DI. Part-time vs. full-time occlusion for amblyopia: evidence for part-time patching. Am Orthopt J. 2013;63:14–8.

DeSantis D. Amblyopia. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2014;61(3):505–18.

Mansouri B, Singh P, Globa A, Pearson P. Binocular training reduces amblyopic visual acuity impairment. Strabismus. 2014;22(1):1–6.

Carlton J, Kaltenthaler E. Amblyopia and quality of life: a systematic review. Eye. 2011;25(4):403–13.

Korah S, Philip S, Jasper S, Antonio-Santos A, Braganza A: Strabismus surgery before versus after completion of amblyopia therapy in children. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2014.

Evans BJ, Yu CS, Massa E, Mathews JE. Randomised controlled trial of intermittent photic stimulation for treating amblyopia in older children and adults. Ophthalmic & Physiological Optics. 2011;31(1):56–68.

Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator G, Repka MX, Kraker RT, Dean TW, Beck RW, Siatkowski RM, Holmes JM, Beauchamp CL, Golden RP, Miller AM, et al. A randomized trial of levodopa as treatment for residual amblyopia in older children. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(5):874–81.

Tsirlin I, Colpa L, Goltz HC, Wong AM. Behavioral training as new treatment for adult amblyopia: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(6):4061–75.

Ivandic BT, Ivandic T. Low-level laser therapy improves visual acuity in adolescent and adult patients with amblyopia. Photomed Laser Surg. 2012;30(3):167–71.

Taylor K, Elliott S. Interventions for strabismic amblyopia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;8:CD006461.

Antonio-Santos A, Vedula SS, Hatt SR, Powell C. Occlusion for stimulus deprivation amblyopia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD005136.

Yan XK, Zhu TT, Ma CB, Liu AG, Dong LL, Wang JY. A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials on Acupuncture for Amblyopia. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011;(8):CD006461. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006461.pub3.

Carlton J, Kaltenthaler E. Health-related quality of life measures (HRQoL) in patients with amblyopia and strabismus: a systematic review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95(3):325–30.

Tadic V, Hogan A, Sobti N, Knowles RL, Rahi JS. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in paediatric ophthalmology: a systematic review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97(11):1369–81.

Piano M, O'Connor AR. Conservative management of intermittent distance exotropia: a review. Am Orthopt J. 2011;61(1):103–16.

Elliott S, Shafiq A. Interventions for infantile esotropia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD004917.

Chen J, Deng D, Zhong H, Lin X, Kang Y, Wu H, Yan J, Mai G. Botulinum toxin injections combined with or without sodium hyaluronate in the absence of electromyography for the treatment of infantile esotropia: a pilot study. Eye. 2013;27(3):382–6.

Simonsz HJ, Kolling GH. Best age for surgery for infantile esotropia. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2011;15(3):205–8.

Hug D. Management of infantile esotropia. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(5):371–4.

Shainberg MJ. Nonsurgical treatment of teenagers with high AC/a ratio esotropia. Am Orthopt J. 2014;64:32–6.

Hatt SR, Wang X, Holmes JM: Interventions for dissociated vertical deviation. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2015.

Christoff A, Raab EL, Guyton DL, Brodsky MC, Fray KJ, Merrill K, Hennessey CC, Bothun ED, Morrison DG. DVD--a conceptual, clinical, and surgical overview. J Aapos: Am Assoc Pedia Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2014;18(4):378–84.

Rajavi Z, Molazadeh A, Ramezani A, Yaseri M. A randomized clinical trial comparing myectomy and recession in the management of inferior oblique muscle overaction. J Pedia Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2011;48(6):375–80.

MacKenzie K, Hancox J, McBain H, Ezra DG, Adams G, Newman S: Psychosocial interventions for improving quality of life outcomes in adults undergoing strabismus surgery. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016.

McBain HB, Au CK, Hancox J, MacKenzie KA, Ezra DG, Adams GGW, Newman SP. The impact of strabismus on quality of life in adults with and without diplopia: a systematic review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2014;59(2):185–91.

Minguini N, de Carvalho KMM, Bosso FLS, Hirata FE, Kara-José N. Surgery with intraoperative botulinum toxin-a injection for the treatment of large-angle horizontal strabismus: a pilot study. Clinics. 2012;67(3):279–82.

Gunton KB. Impact of strabismus surgery on health-related quality of life in adults. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2014;25(5):406–10.

Haridas A, Sundaram V. Adjustable versus non-adjustable sutures for strabismus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018. Issue 3. Art. No.: CD004240. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004240.pub4.

Saxena R, Kakkar A, Menon V, Sharma P, Phuljhele S. Evaluation of factors influencing distance stereoacuity on Frisby-Davis distance test (FD2) in intermittent exotropia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95(8):1098–101.

Yilmaz A, Kose S, Yilmaz SG, Uretmen O. The impact of prism adaptation test on surgical outcomes in patients with primary exotropia. Clin Exp Optometry. 2015;98(3):224–7.

Kelkar J, Gopal S, Shah R, Kelkar A. Intermittent exotropia: Surgical treatment strategies. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2015;63(7):566–9.

Gross NJ, Link H, Biermann J, Kiechle M, Lagreze WA. Induced Incomitance of one muscle strabismus surgery in comparison to unilateral recess-resect procedures. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 2015;232(10):1174–7.

Nabie R, Azadeh M, Andalib D, Mohammadlou FS. Anchored versus conventional hang-back bilateral lateral rectus muscle recession for exotropia. J AAPOS. 2011;15(6):532–5.

Wang B, Wang L, Wang Q, Ren M. Comparison of different surgery procedures for convergence insufficiency-type intermittent exotropia in children. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(10):1409–13.

Wang X, Gao X, Xiao M, Tang L, Wei X, Zeng J, Li Y. Effectiveness of strabismus surgery on the health-related quality of life assessment of children with intermittent exotropia and their parents: a randomized clinical trial. J Aapos: Am Assoc Pedia Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2015;19(4):298–303.

Jones-Jordan L, Wang X, Scherer RW, Mutti DO: Spectacle correction versus no spectacles for prevention of strabismus in hyperopic children. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2014.

Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator G, Cotter SA, Mohney BG, Chandler DL, Holmes JM, Repka MX, Melia M, Wallace DK, Beck RW, Birch EE, et al. A randomized trial comparing part-time patching with observation for children 3 to 10 years of age with intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(12):2299–310.

Mohney BG, Cotter SA, Chandler DL, Holmes JM, Chen AM, Melia M, Donahue SP, Wallace DK, Kraker RT, Christian ML, et al. A randomized trial comparing part-time patching with observation for intermittent exotropia in children 12 to 35 months of age. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(8):1718–25.

Joyce KE, Beyer F, Thomson RG, Clarke MP. A systematic review of the effectiveness of treatments in altering the natural history of intermittent exotropia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(4):440–50.

Clarke M, Hogan V, Buck D, Shen J, Powell C, Speed C, Tiffin P, Sloper J, Taylor R, Nassar M, et al. An external pilot study to test the feasibility of a randomised controlled trial comparing eye muscle surgery against active monitoring for childhood intermittent exotropia [X(T)]. Health Technol Asse (Winchester, England). 2015;19(39):1–144.

Buck D, McColl E, Powell CJ, Shen J, Sloper J, Steen N, Taylor R, Tiffin P, Vale L, Clarke MP. Surgery versus Active Monitoring in Intermittent Exotropia (SamExo): study protocol for a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials [Electronic Resource]. 2012;13:192.

Tailor V, Balduzzi S, Hull S, Rahi J, Schmucker C, Virgili G, Dahlmann-Noor A: Tests for detecting strabismus in children age 1 to 6 years in the community. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2014.

Rowe FJ, Noonan CP, Garcia-Finana M, Dodridge CS, Howard C, Jarvis KA, MacDiarmid SL, Maan T, North L, Rodgers H: Interventions for eye movement disorders due to acquired brain injury. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2014.

Pollock A, Hazelton C, Henderson CA, Angilley J, Dhillon B, Langhorne P, Livingstone K, Munro FA, Orr H, Rowe FJ et al: Interventions for disorders of eye movement in patients with stroke. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2011.

Minakaran N, Ezra Daniel G: Rituximab for thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2013.

Boboridis KG, Bunce C. Surgical orbital decompression for thyroid eye disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD007630.

Rajendram R, Bunce C, Lee Richard WJ, Morley Ana MS: Orbital radiotherapy for adult thyroid eye disease. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012.

Hertle RW, Yang D, Adkinson T, Reed M. Topical brinzolamide (Azopt) versus placebo in the treatment of infantile nystagmus syndrome (INS). Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(4):471–6.