Abstract

Background

The use of Anti-PD-1 therapy has yielded promising outcomes in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, limited research has been conducted on the overall survival (OS) of patients with varying tumor responses and treatment duration.

Methods

This retrospective study analyzed HCC patients who received sintilimab between January 2019 and December 2020 at four centers in China. The evaluation of tumor progression was based on Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1. The study investigated the correlation between tumor response and OS, and the impact of drug use on OS following progressive disease (PD).

Results

Out of 441 treated patients, 159 patients satisfied the inclusion criteria. Among them, 77 patients with disease control exhibited a significantly longer OS compared to the 82 patients with PD (median OS 26.0 vs. 11.3 months, P < 0.001). Additionally, the OS of patients with objective response (OR) was better than that of patients with stable disease (P = 0.002). Among the 47 patients with PD who continued taking sintilimab, the OS was better than the 35 patients who discontinued treatment (median OS 11.4 vs. 6.9 months, P = 0.042).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the tumor response in HCC patients who received sintilimab affects OS, and patients with PD may benefit from continued use of sintilimab.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a major type of primary liver cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1]. Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, including PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors, have shown clinical benefit in various cancers [2,3,4,5,6], and several studies have shown encouraging clinical activity of anti-PD-1 antibodies in previously treated patients with HCC [7, 8]. The combination of PD-1 inhibitors and other systemic or local therapies has also become a major focus [9,10,11,12].

As a type of PD-1 inhibitor, interest in the use of sintilimab for treating HCC has been growing in recent years [13], with several clinical trials conducted to evaluate its safety and efficacy. The ORIENT-32 trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of the combination of sintilimab and IBI305 (a biosimilar of bevacizumab) with sorafenib for the treatment of unresectable HCC patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, and found that the combination significantly improved overall survival and progression-free survival compared to sorafenib alone, with a manageable safety profile [11]. Additionally, the combination of sintilimab with apatinib plus capecitabine or anlotinib also significantly prolonged the overall survival and progression-free survival of advanced HCC patients [14, 15]. Overall, these studies suggest that sintilimab may be a promising therapeutic option for HCC patients.

However, some questions remain about how to rationally use PD-1 inhibitors [16]. On the one hand, whether tumor response, as a short-term prognostic endpoint, reflects the long-term survival of patients who receiving PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors was investigated in one report including multiple cancers but not HCC [17]. On the other hand, there is also no standard for the duration of use of PD-1 inhibitors. The KEYNOTE-006 trial investigated the duration of treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab in the treatment of advanced melanoma, by comparing two different treatment periods. The study found that patients who received a fixed 24-month course of treatment had a significantly higher overall survival rate compared to those who received treatment until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity [18]. Another investigation into the optimal treatment duration of PD-1 inhibitors in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the Checkmate-153 trial. This study compared different treatment times with nivolumab and found that longer treatment durations were associated with improved survival outcomes [19]. In general, the optimal treatment duration for PD-1 inhibitors may vary depending on the specific type of cancer [20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Currently, there is limited research in the field of HCC.

This study aimed to describe the overall survival (OS) of patients with different responses after treatment with sintilimab and to determine whether treatment discontinuation in patients with progressive disease (PD) has an impact on OS.

Methods

Patients

A retrospective study of HCC patients received sintilimab therapy between 2019 and 2020 at the Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital, the Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital, the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University and the Yueyang Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine was performed.

The inclusion criteria were patients (1) with unresectable HCC diagnosed by histology, cytology, or clinical characteristics according the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease criteria, (2) with good liver function (Child–Pugh liver function score < = 7), (3) who had previously been treated and were either intolerant to the treatment, exhibited an incomplete response, or showed radiographic progression of their disease after treatment. The exclusion criteria were (1) use of sintilimab for postoperative adjuvant therapy and (2) history of other cancers.

Procedures

Sintilimab was administered intravenously, 200 mg every 3 weeks. If low-grade infusion reactions occurred, the dose should be reduced or treatment should be suspended. When symptoms resolved, treatment was resumed with close observation. The specific doses and protocols used were strictly in accordance with the instructions for use.

In patients whose tumors were under control, sintilimab was continued until disease progression or intolerable toxicities occurred. In this retrospective study, we reviewed the medical records of patients with HCC who had received sintilimab. When patients experienced disease progression during the course of sintilimab use, multidisciplinary consultation was documented in the medical records. Patients were informed of the potential benefits and possible risks of continuing sintilimab, and the decision to continue the treatment was based on the documented consultation between the patient and doctors, while ensuring normal liver function.

Follow-up and evaluation

Patients were followed up every 6 weeks for the first 6 months, every 3 months for the second half year, and every 6 months thereafter. At each follow-up visit, routine physical examination, laboratory blood tests, and abdominal ultrasound or enhanced CT/MRI were performed. The primary endpoint of this study was OS, which was defined as the time from first use of sintilimab to death due to any cause or the last follow-up (August 2, 2021). Assessment of tumor progression was based on Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1. The definition of tumor response is as follows: complete response (CR), in which all target lesions determined by radiographic studies have disappeared; partial response (PR), in which the sum of the diameters of target lesions has decreased by at least 30%, with no new lesions and no progression of non-target lesions; stable disease (SD), in which there is neither sufficient shrinkage to qualify for PR nor sufficient increase to qualify for PD; PD, in which the sum of the diameters of target lesions has increased by at least 20%, or new lesions have appeared; disease control (DC), which encompasses CR, PR, and SD as composite endpoints; objective response (OR), which includes CR and PR as composite endpoints. Best response refers to the most favorable tumor response observed during the course of treatment. Because tumor response assessment at a fixed time point may miss late responders and is affected by the duration of response, we performed an analysis of the time point to best response, which is more appropriate but varies from patient to patient.

Statistical analyses

All clinical data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23 (New York, NY, USA) or R 4.0 software (http://www.r-project.org/). Student’s t test was used to compare continuous variables, and the χ2 test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test.

The time of the highest hazard rate of tumor control or progression during anti-PD-1 therapy was calculated by the hazard function. The hazard function has been well characterized in the context of colorectal and breast cancer [27,28,29]. Patients who did not have an event at time t were analyzed for risk of an event by the hazard function. In contrast, the Kaplan–Meier method identifies the cumulative event risk for the entire cohort at time t [30]. In other words, the hazard function assessed the instantaneous risk. The kernel-smoothing method was used to estimate the hazard rates [31]. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

Results

Population description

From January 2019 to December 2020, 441 patients had been treated with sintilimab in the Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital, and among these patients, after exclusions (260 patients received postoperative adjuvant therapy, and 22 patients had a history of other tumors), 159 patients were included in this study (Fig. 1). The patients’ prior therapies are detailed in Supplementary Table 1. During treatment, there were 6 (3.8%) patients with CR, 46 (28.9%) patients with PR, 25 (15.7%) patients with SD, and 82 patients with PD (51.6%). The patient characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

Overall survival of patients

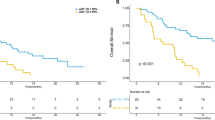

The median follow-up of the studied patients was 11 months (range, 3–29 months), with a median OS of 24.5 months (95% CI, 20.6–28.5, Fig. 2A). Among the patients, 77 patients with DC, and the median OS of these patients was 26.0 months (IQR 24.5–26.0), which was significantly higher than the 11.3 months (95% CI 9.1–13.4, P < 0.001) of patients with PD (Fig. 2B). There were no deaths among the 52 patients with OR, and the median OS of the 25 patients with SD was 24.5 months (95% CI 8.7–40.4, P = 0.002, Fig. 2C).

Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival. A All patients included in the study; B patients with disease control and progressive disease; and C patients with objective response, stable disease, and progressive disease. PD progressive disease, DC disease control, OR objective response, SD stable disease

Multivariate regression analysis showed that direct bilirubin > 17.1 µmol/L, extrahepatic metastases, and DC were independent risk factors for OS in patients treated with sintilimab (Table 2).

Hazard rate of tumor response or progression

The median number of sintilimab administrations was not reached in patients who achieved objective tumor response (Supplementary Fig. 1A), and the median number of sintilimab administrations of PD was 9 (95% CI 8.13–9.86, Supplementary Fig. 1B). The hazard function for OR is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1C, and the shape of the OR hazard rate curve over time revealed variation in OR risk. The hazard rate curve of OR patients showed an initial upward trend followed by a downward trend, with the highest hazard rate (0.078) occurring between the third and fourth use of sintilimab, and the hazard rate dropping to zero between the ninth and tenth use. The hazard function for PD is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1D. The risk of patients with PD tended to increase first and then decrease, reaching the highest hazard rate (0.24) between ninth and tenth use.

Prognosis of patients with PD

During the follow-up period, a total of 82 patients experienced disease progression. Among them, 47 patients continued to receive sintilimab in combination with other treatments, including 30 patients receiving lenvatinib, 13 patients receiving sorafenib, and 4 patients receiving regorafenib. On the other hand, 35 patients discontinued sintilimab but received other treatments, including 21 patients receiving lenvatinib, 10 patients receiving sorafenib, 3 patients receiving regorafenib, and 1 patient abandoning treatment. Baseline characteristics showed no significant differences between the two groups, as shown in Table 3.

In the cohort of patients experiencing disease progression, the discontinuation group had 25 patients who died (18 due to disease progression and 7 due to hepatic failure), while the continuation group had 23 patients who died (15 due to disease progression, 8 due to hepatic failure). When using the start of sintilimab treatment as the starting point, the median OS was 13.4 months (95% CI 6.8–20.0) in the continuation group and 7.9 months (95% CI 4.8–11.0) in the discontinuation group, with no significant difference between the two groups (HR = 0.582, 95% CI 0.330–1.029, P = 0.059, Fig. 3A). When setting the starting point as occurrence of PD, the median OS was 11.4 months (95% CI 6.0-16.8) in the continuation group, which was significantly higher than the 6.9 months (95% CI 4.8–9.1) in the discontinuation group (HR = 0.559, 95% CI 0.316–0.987, P = 0.042, Fig. 3B).

Regarding safety, as shown in Table 4, the most common treatment emergent adverse event associated with sintilimab of any grade in the continuation group was fatigue (10.6%). The most common grade 3/4 adverse event was elevated aspartate aminotransferase (4.2%).

The hazard function for death is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. The highest death hazard rate was 0.055 in the continued treatment group, while it was 0.11 in the treatment discontinuation group.

Discussion

This study has made two main findings. Firstly, tumor response in patients treated with sintilimab was correlated with long-term prognosis, with patients exhibiting a better tumor response having a more favorable prognosis. And we have generated hazard curves for tumor objective response and disease progression. Secondly, patients who experienced disease progression may still benefit from subsequent treatment with sintilimab. The findings of this study may have significant implications for the clinical use of sintilimab and subsequent trial design.

The present international guidelines for the clinical management of HCC suggest the use of systemic therapies for patients with advanced or intermediate stages who progress to chemoembolization [32,33,34]. However, in the case of HCC, the accuracy of radiological response assessment using RECIST criteria has been questioned due to the finding that some therapies can significantly improve survival despite a very low response rate [35]. The EVOLVE-1 trial evaluated the efficacy of everolimus in treating advanced HCC patients who had previously failed sorafenib treatment. The study found that compared to placebo, everolimus significantly improved DCR in this patient population, but did not improve OS [36]. However, in the recent IMbrave150 trial, patients treated with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab had better ORR and OS compared to Sorafenib [37]. This suggests that the relationship between tumor response and long-term survival may not be constant across different systemic treatments for HCC. In our study, the tumor response of patients receiving sintilimab indeed impacted long-term survival. The overall survival of patients with OR was superior to those with SD and PD. This outcome is in line with previous reports, and given that OR is a favorable prognostic feature, it is not surprising [38]. In daily practice, clinicians often pay more attention to patients with PD and change treatment methods to improve their long-term prognosis. However, the OS of patients with SD was also worse than that of patients with OR, and perhaps more aggressive treatment should be considered to prolong the OS of these patients. According to the hazard rate curve, the highest hazard rate for achieving objective tumor response occurs between the use of the third and fourth doses of sintilimab, indicating a time interval between the initiation of immunotherapy and its benefit [39,40,41]. The highest risk time for disease progression is between the ninth and tenth use of sintilimab, which may be due to the emergence of acquired resistance [42].

Furthermore, we conducted a subgroup analysis on patients with disease progression. The results indicated that compared to the discontinuation group, the group that continued to receive treatment had a better OS. The discontinuation group had higher rates of progression and peak hazard of death than the group that continued treatment. This may be due to the fact that some patients have a longer response time to sintilimab, or due to a synergistic effect between PD-1 inhibitors and local regional therapy [43,44,45,46]. Furthermore, no unexpected adverse events were observed in the group of patients continuing to receive sintilimab. The above evidence suggests that for patients receiving sintilimab, treatment should not be simply discontinued even if tumor progression occurs. The risk of discontinuing anti-PD-1 therapy has also been reported in previous studies, such as in advanced melanoma patients with PR or SD who had a higher risk of disease progression after discontinuation than patients with CR [47], possibly due to discontinuation of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition. Rapid antibody clearance results in a short on-target treatment lifespan in the local tumor environment [48]. Furthermore, resistance to the target agent may also develop when chronic PD-1/PD-L1 blockade is lifted [49].

The findings of this study may provide guidance for the design of future clinical trials involving sintilimab. Even in the case of disease progression, some patients may still benefit from sintilimab after thorough evaluation. Furthermore, longer follow-up of patients with PD to investigate the mechanisms of the innate immune system and prospective trials aimed at evaluating the duration of treatment for patients after progression (the second randomization of patients with PD) may help confirm our findings. Additionally, further research is needed to determine if timely changes in treatment plans for patients with SD can improve OS.

We must acknowledge the limitations of our study. First, this is a retrospective study with inherent deficiencies, and the PD-L1 expression of the tumor could not be determined. Second, this was a study conducted in China, a hepatitis B virus (HBV)-endemic area, which may have influenced the results. Third, the heterogeneity of patients’ treatment history before receiving sintilimab may have had an impact on the results.

In conclusion, tumor response in HCC patients treated with sintilimab affects the OS, and sintilimab should be used for a fixed period of time to prevent premature discontinuation of therapy due to pseudoprogression. And regular follow-up is necessary for patients receiving long-term sintilimab treatment to prevent adverse outcomes due to drug resistance, and that continued use of sintilimab in combination with other therapies may be beneficial for patients with disease progression but without intolerable toxicity. However, it is important to note that the retrospective nature of the study limits the strength of the conclusions that can be drawn. Additional research, such as prospective studies and randomized controlled trials, are needed to further explore the potential benefits and risks of long-term sintilimab use and determine the optimal treatment strategies for patients with HCC.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- PD:

-

Progressive disease

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- CR:

-

Complete response

- PR:

-

Partial response

- SD:

-

Stable disease

- DC:

-

Disease control

- OR:

-

Objective response

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660.

Kato K, Cho BC, Takahashi M, Okada M, Lin CY, Chin K, Kadowaki S, Ahn MJ, Hamamoto Y, Doki Y, Kato K, Cho BC, Takahashi M, Okada M, Lin C-Y, Chin K, Kadowaki S, Ahn M-J, Hamamoto Y, Doki Y, Yen C-C, Kubota Y, Kim S-B, Hsu C-H, Holtved E, Xynos I, Kodani M, Kitagawa Y. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma refractory or intolerant to previous chemotherapy (ATTRACTION-3): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(11):1506–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30626-6.

Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csoszi T, Fulop A, Gottfried M, Peled N, Tafreshi A, Cuffe S, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive non-small-cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823–33.

Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N, Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, Patnaik A, Aggarwal C, Gubens M, Horn L, Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N, Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, Patnaik A, Aggarwal C, Gubens M, Horn L, Carcereny E, Ahn M-J, Felip E, Lee J-S, Hellmann MD, Hamid O, Goldman JW, Soria J-C, Dolled-Filhart M, Rutledge RZ, Zhang J, Lunceford JK, Rangwala R, Lubiniecki GM, Roach C, Emancipator K, Gandhi L. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):2018–28. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1501824.

Chuma M, Uojima H, Hattori N, Arase Y, Fukushima T, Hirose S, Kobayashi S, Ueno M, Tezuka S, Iwasaki S, Chuma M, Uojima H, Hattori N, Arase Y, Fukushima T, Hirose S, Kobayashi S, Ueno M, Tezuka S, Iwasaki S, Wada N, Kubota K, Tsuruya K, Shimma Y, Hiroki I, Takuya E, Tokoro C, Iwase S, Miura Y, Moriya S, Watanabe T, Hidaka H, Morimoto M, Numata K, Kusano C, Kagawa T, Maeda S. Safety and efficacy of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in early clinical practice: a multicenter analysis. Hepatol Res. 2022;52(3):269–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.13732.

Ghavimi S, Apfel T, Azimi H, Persaud A, Pyrsopoulos NT. Management and treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Immunotherapy: a review of current and future options. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2020;8(2):168–76. https://doi.org/10.14218/JCTH.2020.00001.

El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, Crocenzi TS, Kudo M, Hsu C, Kim TY, Choo SP, Trojan J, Welling THR, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10088):2492–502.

Zhu AX, Finn RS, Edeline J, Cattan S, Ogasawara S, Palmer D, Verslype C, Zagonel V, Fartoux L, Vogel A, Zhu AX, Finn RS, Edeline J, Cattan S, Ogasawara S, Palmer D, Verslype C, Zagonel V, Fartoux L, Vogel A, Sarker D, Verset G, Chan SL, Knox J, Daniele B, Webber AL, Ebbinghaus SW, Ma J, Siegel AB, Cheng A-L, Kudo M, Alistar A, Asselah J, Blanc J-F, Borbath I, Cannon T, Chung Ki, Cohn A, Cosgrove DP, Damjanov N, Gupta M, Karino Y, Karwal M, Kaubisch A, Kelley R, Van Laethem J-L, Larson T, Lee J, Li D, Manhas A, Manji GA, Numata K, Parsons B, Paulson AS, Pinto C, Ramirez R, Ratnam S, Rizell M, Rosmorduc O, Sada Y, Sasaki Y, Stal PI, Strasser S, Trojan J, Vaccaro G, Van Vlierberghe H, Weiss A, Weiss K-H, Yamashita T. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE-224): a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(7):940–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30351-6.

Yau T, Kang YK, Kim TY, El-Khoueiry AB, Santoro A, Sangro B, Melero I, Kudo M, Hou MM, Matilla A, Yau T, Kang Y-K, Kim T-Y, El-Khoueiry AB, Santoro A, Sangro B, Melero I, Kudo M, Hou M-M, Matilla A, Tovoli F, Knox JJ, Ruth He A, El-Rayes BF, Acosta-Rivera M, Lim H-Y, Neely J, Shen Y, Wisniewski T, Anderson J, Hsu C. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab plus ipilimumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib: the CheckMate 040 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(11):e204564. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.4564.

Llovet JM, De Baere T, Kulik L, Haber PK, Greten TF, Meyer T, Lencioni R. Locoregional therapies in the era of molecular and immune treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(5):293–313.

Ren Z, Xu J, Bai Y, Xu A, Cang S, Du C, Li Q, Lu Y, Chen Y, Guo Y, Ren Z, Xu J, Bai Y, Xu A, Cang S, Du C, Li Q, Lu Y, Chen Y, Guo Y, Chen Z, Liu B, Jia W, Wu J, Wang J, Shao G, Zhang B, Shan Y, Meng Z, Wu J, Gu S, Yang W, Liu C, Shi X, Gao Z, Yin T, Cui J, Huang M, Xing B, Mao Y, Teng G, Qin Y, Wang J, Xia F, Yin G, Yang Y, Chen M, Wang Y, Zhou H, Fan J. Sintilimab plus a bevacizumab biosimilar (IBI305) versus sorafenib in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (ORIENT-32): a randomised, open-label, phase 2–3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(7):977–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00252-7.

Dong Y, Wong JSL, Sugimura R, Lam KO, Li B, Kwok GGW, Leung R, Chiu JWY, Cheung TT, Yau T. Recent advances and future prospects in Immune Checkpoint (ICI)-Based combination therapy for Advanced HCC. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(8):1949.

Chen J, Hu X, Li Q, Dai W, Cheng X, Huang W, Yu W, Chen M, Guo Y, Yuan G. Effectiveness and safety of toripalimab, camrelizumab, and sintilimab in a real-world cohort of hepatitis B virus associated hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(18):1187–1187. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-6063.

Chen X, Li W, Wu X, Zhao F, Wang D, Wu H, Gu Y, Li X, Qian X, Hu J, Chen X, Li W, Wu X, Zhao F, Wang D, Wu H, Gu Y, Li X, Qian X, Hu J, Li C, Xia Y, Rao J, Dai X, Shao Q, Tang J, Li X, Shu Y. Safety and Efficacy of Sintilimab and Anlotinib as First Line treatment for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma (KEEP-G04): a single-arm phase 2 study. Front Oncol. 2022;12: 909035. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.909035.

Li D, Xu L, Ji J, Bao D, Hu J, Qian Y, Zhou Y, Chen Z, Li D, Li X, Li D, Xu Lu, Ji J, Bao D, Hu J, Qian Y, Zhou Y, Chen Z, Li D, Li X, Zhang X, Wang H, Yi C, Shi M, Pang Y, Liu S, Xu X. Sintilimab combined with apatinib plus capecitabine in the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective, open-label, single-arm, phase II clinical study. Front Immunol. 2022;13: 944062. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.944062.

Cheng L, Xiao H. Sintilimab plus IBI305 for hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(9):e387. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00424-1.

Gauci ML, Lanoy E, Champiat S, Caramella C, Ammari S, Aspeslagh S, Varga A, Baldini C, Bahleda R, Gazzah A, Gauci M-L, Lanoy E, Champiat S, Caramella C, Ammari S, Aspeslagh S, Varga A, Baldini C, Bahleda R, Gazzah A, Michot J-M, Postel-Vinay S, Angevin E, Ribrag V, Hollebecque A, Soria J-C, Robert C, Massard C, Marabelle A. Long-term survival in patients responding to Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy and Disease Outcome upon Treatment Discontinuation. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(3):946–56. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0793.

Robert C, Ribas A, Schachter J, Arance A, Grob JJ, Mortier L, Daud A, Carlino MS, McNeil CM, Lotem M, Robert C, Ribas A, Schachter J, Arance A, Grob J-J, Mortier L, Daud A, Carlino MS, McNeil CM, Lotem M, Larkin JMG, Lorigan P, Neyns B, Blank CU, Petrella TM, Hamid O, Su S-C, Krepler C, Ibrahim N, Long GV. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma (KEYNOTE-006): post-hoc 5-year results from an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(9):1239–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30388-2.

Waterhouse DM, Garon EB, Chandler J, McCleod M, Hussein M, Jotte R, Horn L, Daniel DB, Keogh G, Creelan B, et al. Continuous versus 1-Year fixed-duration nivolumab in previously treated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: CheckMate 153. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(33):3863–73.

de Velasco G, Krajewski KM, Albiges L, Awad MM, Bellmunt J, Hodi FS, Choueiri TK. Radiologic heterogeneity in responses to Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4(1):12–7. https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0197.

Grothey A, Sugrue MM, Purdie DM, Dong W, Sargent D, Hedrick E, Kozloff M. Bevacizumab beyond first progression is associated with prolonged overall survival in metastatic colorectal cancer: results from a large observational cohort study (BRiTE). J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(33):5326–34. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3212.

Puzanov I, Amaravadi RK, McArthur GA, Flaherty KT, Chapman PB, Sosman JA, Ribas A, Shackleton M, Hwu P, Chmielowski B, et al. Long-term outcome in BRAF(V600E) melanoma patients treated with vemurafenib: patterns of disease progression and clinical management of limited progression. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(11):1435–43.

von Minckwitz G, du Bois A, Schmidt M, Maass N, Cufer T, de Jongh FE, Maartense E, Zielinski C, Kaufmann M, Bauer W, von Minckwitz G, du Bois A, Schmidt M, Maass N, Cufer T, de Jongh FE, Maartense E, Zielinski C, Kaufmann M, Bauer W, Baumann KH, Clemens MR, Duerr R, Uleer C, Andersson M, Stein RC, Nekljudova V, Loibl S. Trastuzumab beyond progression in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive advanced breast cancer: a german breast group 26/breast international group 03–05 study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(12):1999–2006. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6618.

Wolchok JD, Hoos A, O’Day S, Weber JS, Hamid O, Lebbe C, Maio M, Binder M, Bohnsack O, Nichol G, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: immune-related response criteria. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(23):7412–20.

Burotto M, Wilkerson J, Stein W, Motzer R, Bates S, Fojo T. Continuing a cancer treatment despite tumor growth may be valuable: sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma as example. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5): e96316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096316.

Ou SH, Janne PA, Bartlett CH, Tang Y, Kim DW, Otterson GA, Crino L, Selaru P, Cohen DP, Clark JW, Ou S-H- I, Jänne PA, Bartlett CH, Tang Y, Kim D-W, Otterson GA, Crinò L, Selaru P, Cohen DP, Clark JW, Riely GJ. Clinical benefit of continuing ALK inhibition with crizotinib beyond initial disease progression in patients with advanced ALK-positive NSCLC. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(2):415–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt572.

Kudose Y, Shida D, Ahiko Y, Nakamura Y, Sakamoto R, Moritani K, Tsukamoto S, Kanemitsu Y. Evaluation of recurrence risk after curative resection for patients with stage I to III colorectal Cancer using the hazard function: retrospective analysis of a single-institution large cohort. Ann Surg. 2020;275(4):727–34. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000004058.

Colleoni M, Sun Z, Price KN, Karlsson P, Forbes JF, Thurlimann B, Gianni L, Castiglione M, Gelber RD, Coates AS, Colleoni M, Sun Z, Price KN, Karlsson P, Forbes JF, Thürlimann B, Gianni L, Castiglione M, Gelber RD, Coates AS, Goldhirsch A. Annual Hazard Rates of recurrence for breast Cancer during 24 years of Follow-Up: results from the international breast Cancer Study Group trials I to V. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(9):927–35. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.62.3504.

Cheng L, Swartz MD, Zhao H, Kapadia AS, Lai D, Rowan PJ, Buchholz TA, Giordano SH. Hazard of recurrence among women after primary breast cancer treatment–a 10-year follow-up using data from SEER-Medicare. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(5):800–9. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1089.

Hess KR, Levin VA. Getting more out of survival data by using the hazard function. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(6):1404–9. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2125.

Muller HG, Wang JL. Hazard rate estimation under random censoring with varying kernels and bandwidths. Biometrics. 1994;50(1):61–76. https://doi.org/10.2307/2533197.

Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, Zhu AX, Finn RS, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, Heimbach JK. Diagnosis, staging, and management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68(2):723–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29913.

EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69(1):182–236.

Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, Ferrer-Fàbrega J, Burrel M, Garcia-Criado Á, Kelley RK, Galle PR, Mazzaferro V, Salem R, Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, Ferrer-Fàbrega J, Burrel M, Garcia-Criado Á, Kelley RK, Galle PR, Mazzaferro V, Salem R, Sangro B, Singal AG, Vogel A, Fuster J, Ayuso C, Bruix J. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: the 2022 update. J Hepatol. 2022;76(3):681–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.018.

Llovet JM, Lencioni R. mRECIST for HCC: performance and novel refinements. J Hepatol. 2020;72(2):288–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.09.026.

Zhu AX, Kudo M, Assenat E, Cattan S, Kang YK, Lim HY, Poon RT, Blanc JF, Vogel A, Chen CL, et al. Effect of everolimus on survival in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma after failure of sorafenib: the EVOLVE-1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(1):57–67.

Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, Kudo M, Breder V, Merle P, Kaseb AO, Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim T-Y, Kudo M, Breder V, Merle P, Kaseb AO, Li D, Verret W, Xu D-Z, Hernandez S, Liu J, Huang C, Mulla S, Wang Y, Lim HY, Zhu AX, Cheng A-L. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1894–905. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1915745.

Kudo M, Montal R, Finn RS, Castet F, Ueshima K, Nishida N, Haber PK, Hu Y, Chiba Y, Schwartz M, Kudo M, Montal R, Finn RS, Castet F, Ueshima K, Nishida N, Haber PK, Hu Y, Chiba Y, Schwartz M, Meyer T, Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Objective response predicts survival in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma treated with systemic therapies. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28(16):3443–51. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-3135.

Motzer RJ, Rini BI, McDermott DF, Redman BG, Kuzel TM, Harrison MR, Vaishampayan UN, Drabkin HA, George S, Logan TF, Motzer RJ, Rini BI, McDermott DF, Redman BG, Kuzel TM, Harrison MR, Vaishampayan UN, Drabkin HA, George S, Logan TF, Margolin KA, Plimack ER, Lambert AM, Waxman IM, Hammers HJ. Nivolumab for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a Randomized Phase II Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(13):1430–7. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.59.0703.

Daud AI, Wolchok JD, Robert C, Hwu WJ, Weber JS, Ribas A, Hodi FS, Joshua AM, Kefford R, Hersey P, Daud AI, Wolchok JD, Robert C, Hwu W-J, Weber JS, Ribas A, Hodi FS, Joshua AM, Kefford R, Hersey P, Joseph R, Gangadhar TC, Dronca R, Patnaik A, Zarour H, Roach C, Toland G, Lunceford JK, Li XN, Emancipator K, Dolled-Filhart M, Kang SP, Ebbinghaus S, Hamid O. Programmed death-ligand 1 expression and response to the Anti-Programmed death 1 antibody Pembrolizumab in Melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(34):4102–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.67.2477.

Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, Drake CG, Camacho LH, Kauh J, Odunsi K, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2455–65.

De Lorenzo S, Tovoli F, Trevisani F. Mechanisms of primary and acquired resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(19):4616.

Guo J, Wang S, Han Y, Jia Z, Wang R. Effects of transarterial chemoembolization on the immunological function of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2021;22(1):554. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2021.12815.

Hiroishi K, Eguchi J, Baba T, Shimazaki T, Ishii S, Hiraide A, Sakaki M, Doi H, Uozumi S, Omori R, et al. Strong CD8(+) T-cell responses against tumor-associated antigens prolong the recurrence-free interval after tumor treatment in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45(4):451–8.

Bernstein MB, Krishnan S, Hodge JW, Chang JY. Immunotherapy and stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (ISABR): a curative approach? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13(8):516–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.30.

Romano E, Honeychurch J, Illidge TM. Radiotherapy-Immunotherapy combination: how will we bridge the gap between pre-clinical promise and effective clinical delivery? Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(3):457.

Jansen YJL, Rozeman EA, Mason R, Goldinger SM, Geukes Foppen MH, Hoejberg L, Schmidt H, van Thienen JV, Haanen J, Tiainen L, et al. Discontinuation of anti-PD-1 antibody therapy in the absence of disease progression or treatment limiting toxicity: clinical outcomes in advanced melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(7):1154–61.

Arlauckas SP, Garris CS, Kohler RH, Kitaoka M, Cuccarese MF, Yang KS, Miller MA, Carlson JC, Freeman GJ, Anthony RM, et al. In vivo imaging reveals a tumor-associated macrophage-mediated resistance pathway in anti-PD-1 therapy. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(389):eaal3604.

Ramos P, Bentires-Alj M. Mechanism-based cancer therapy: resistance to therapy, therapy for resistance. Oncogene. 2015;34(28):3617–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2014.314.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Clinical Research Plan of Shanghai Hospital Development Center (No. SHDC2020CR1004A), the State Key Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 81730097), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 82072618).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Shu-Qun Cheng, Kang Wang, and Yan-Jun XiangFunding acquisition: Shu-Qun Cheng, Kang WangResources: Kang Wang, Hong-Ming Yu, Yu-Qiang Cheng, Yun-Feng Shan, Shu-Qun ChengInvestigation: Kang Wang, Yan-Jun Xiang, Hong-Ming Yu, Jin-Kai Feng, Zong-Han Liu, Yi-Tao Zheng, Qian-Zhi Ni, Shu-Qun ChengFormal analysis: Kang Wang, Yan-Jun Xiang, and Hong-Ming YuWriting–original draft: Kang Wang, Yan-Jun Xiang, and Hong-Ming Yu Writing–review & editing: All authors All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was in compliance with the ethical standards of Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital as the main center (EHBHKY2021-K-026). The need for written informed consent was waived by the Institutional Ethics Committee due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, K., Xiang, YJ., Yu, HM. et al. Overall survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sintilimab and disease outcome after treatment discontinuation. BMC Cancer 23, 1017 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-11485-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-11485-y