Abstract

Background

The impact of sarcopenia on the outcome of patients with left-sided colon and rectal cancer has not been exhaustively investigated. Thus, the present study was performed to evaluate the effect of sarcopenia on the outcome of patients with left-sided colon and rectal cancer.

Methods

Patients with pathologically diagnosed stage I, II and III left-sided colon or rectal cancer who had undergone curative surgery between January 2008 and December 2014 were retrospectively reviewed. The psoas muscle index (PMI) identified by 3D-image analysis of computed tomographic images was the criterion used to diagnose sarcopenia. The cut-off value recommended by Hamaguchi (PMI value < 6.36 cm2/m2 for men and < 3.92 cm2/m2 for women) was adopted to confirm the diagnosis of sarcopenia. According to the PMI, each patient was divided into the sarcopenia group (SG) or the nonsarcopenia group (NSG). Then, the SG was compared with the NSG in terms of postoperative outcomes.

Results

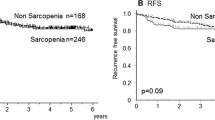

Among the 939 patients included, 574 (61.1%) were confirmed to have preoperative sarcopenia. Initially, it was demonstrated that the SG was not significantly different from the NSG in terms of most baseline characteristics except for a lower body mass index (BMI) (P < 0.001), a larger tumour size (P < 0.001) and more weight loss (more than 3 kg in the last three months) (P = 0.033). The SG had a longer hospital stay after surgery (P = 0.040), more intraoperative blood transfusions (P = 0.035), and higher incidence of anastomotic fistula (P = 0.027), surgical site infection (SSI) (P = 0.037) and hypoalbuminemia (P = 0.022), 30-day mortality (P = 0.042) and 90-day mortality (P = 0.041). The SG had significantly worse overall survival (OS) (P = 0.016) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) (P = 0.036) than the NSG. Subsequently, Cox regression analysis revealed that preoperative sarcopenia was an independent predictive factor for worse OS (P = 0.0211, HR = 1.367, 95% CI: 1.049–1.782) and RFS (P = 0.045, HR = 1.299, 95% CI: 1.006–1.677).

Conclusion

Preoperative sarcopenia adversely affects the outcome of patients with left-sided colon and rectal cancer, and preoperative nutrition supplementation may help us improve their long-term and short-term outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide and causes the second most cancer-related deaths [1]. Left-sided colon cancer and rectal cancer are the most commonly diagnosed. Over the past few decades, the survival of patients with CRC has been remarkably improved due to the popularization of the multidisciplinary teamwork (MDT) mode and the application of more treatment modalities.

Many studies have reported the significance of nutritional status among patients with CRC. Ashna Gupta reported that preoperative malnutrition in patients with colorectal cancer is associated with several postoperative consequences and poorer prognosis [2]. Moreover, malnutrition was more commonly encountered among patients with CRC. They argued that reasonable nutritional supplementation was of paramount significance to achieve favourable short-term outcomes and long-term survival [2]. As a unique type of malnutrition, sarcopenia has been evaluated among various cancers. According to a review by Papadopoulou SK, a progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass and loss of muscle function is defined as sarcopenia, and sarcopenia is currently considered as a prevalent health problem among elderly patients [3]. Two types of sarcopenia, primary and secondary sarcopenia have been proposed. Age-associated loss of muscle mass is defined as primary sarcopenia, while loss of muscle mass secondary to pathogenic diseases is defined as secondary sarcopenia [4, 5]. In an ageing society, sarcopenia among patients diagnosed with cancer not only includes secondary sarcopenia but also age-associated primary sarcopenia, but sometimes both types exist. In most studies, primary sarcopenia is not distinguished from secondary sarcopenia, and as a matter of fact, it is not easy to differentiate primary sarcopenia from secondary sarcopenia. Sarcopenia has been reported to lead to worse prognosis [6], especially for those with malignant tumours [7,8,9,10,11]. Similarly, sarcopenia has also been evaluated in CRC in a few studies, and sarcopenia has been identified as a negative prognostic factor for CRC [12, 13].

However, studies investigating the prognostic significance of preoperative sarcopenia among CRC patients are still scarce. Previous studies have included fewer patients. Additionally, it has been reported that right-sided colon cancer is significantly different from left-sided colon and rectal cancer in terms of long-term prognosis and cancer biology [14,15,16]. However, to the best of our knowledge, studies investigating the prognostic significance of sarcopenia among patients with left-sided colon or rectal cancer remain scarce. Therefore, the present study was performed to investigate the impacts of preoperative sarcopenia on the short-term and long-term outcomes of patients with left-sided colon or rectal cancer.

Methods

Patients and ethical approval

Patients with pathologically diagnosed left-sided colon or rectal cancer who had undergone curative surgery between January 2008 and December 2014 at The Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine were retrospectively reviewed. However, patients suffering from complete obstruction, perforation and hemorrhage had been excluded from this study since these patients were usually dealt with by emergent surgeries. And emergent surgeries were more likely to result in higher morbidity rate. Before surgery, all the patients, especially those diagnosed with rectal cancer, were discussed by experts of different disciplines (i.e., MDT mode). Patients with rectal cancer routinely received magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess the depth of invasion and lymph node metastasis. Preoperatively, for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer identified by MRI, medical oncologists and radiotherapists were consulted to assess indications and contraindications for neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Similarly, after curative surgery, medical oncologists and radiotherapists were consulted to evaluate the adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy given. The exclusion criteria adopted in this study were as follows: palliative surgery, systematic inflammation due to aetiologies other than colorectal cancer, insufficient follow-up information, synchronous or heterochronous colorectal cancer and malignant tumours of other organs. This study was approved by The Ethics Committee, The First Affiliated Hospital, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (approval number: K2022-077). All the patients included in this study provided informed consent in written form. The following variables were included in this study: body mass index (BMI), age, gender, hypertension, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, comorbidity, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [17, 18], weight loss (more than 3 kg in the last three months), intestinal obstruction (preoperative), tumour size, tumour location, gross morphology, tumour grading, histological component, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, depth of invasion, lymph node metastasis, the number of harvested lymph nodes, Union Internationale Against cancer and American joint Committee on cancer(AJCC/UICC) stage, CEA, CA19.9, adjuvant chemotherapy, and postoperative complications. Postoperative complications were graded by the Clavien Dindo system [19]. The present study was in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki during the whole process [20].

Measurement of the psoas muscle index (PMI) and definition of sarcopenia

The cross-sectional areas of the psoas muscles at the level of the third lumbar vertebra (L3) on computed tomography (CT) were measured using IntelliSpace Portal (Version 10, Philips Health System, Best, Netherlands; Licence number 85954) (Fig. 1A-D). The PMI of each patient was obtained by dividing the area of the psoas muscle by the square of the height (m). Hamaguchi proposed that the PMI should be adopted as a diagnostic criterion for sarcopenia, and he proposed that a PMI < 6.36 cm2/m2 for male patients and a PMI < 3.92 cm2/m2 for female patients should be adopted to diagnose sarcopenia [21]. Similarly, the criteria proposed by Hamaguchi et al. were also adopted in this study. According to the PMI, each patient was assigned to the sarcopenia group (SG) or nonsarcopenia group (NSG).

A Measuring the cross-sectional area of the psoas muscles at the level of the third lumbar vertebra for a patient with sarcopenia and sigmoid colon cancer. B Representative CT image of a patient diagnosed with sigmoid colon cancer and sarcopenia. C Measuring the cross-sectional area of the psoas muscles at the level of the third lumbar vertebra for a patient with sigmoid colon cancer but without sarcopenia. D Representative CT image of a patient diagnosed with sigmoid colon cancer but without sarcopenia

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared using the t test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test, while categorical variables were compared by Fisher’s exact test. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time length between curative surgery and death regardless of the cause, while the duration between curative surgery and cancer recurrence was recorded as recurrence-free survival (RFS). The Kaplan‒Meier method was used to calculate OS and RFS. The statistical significance of each comparison between SG and NSG was identified by the log-rank test. Cox regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictive factors for OS and RFS. The SG was compared with the NSG in terms of preoperative variables and postoperative outcomes. All the tests performed in this study were two-sided, and P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The aforementioned statistical analyses were accomplished by the Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) software package (Version 22, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the SG and NSG are summarized in Table 1. The SG included significantly more patients who had a remarkably lower body mass index, which was consistent with previous studies [22, 23]. The SG included 574 patients, while there were 365 patients in the NSG. The SG was not significantly different from the NSG in terms of most of the baseline characteristics except for a significantly lower BMI (P < 0.001), a larger tumour size (P < 0.001), and more weight loss (more than 3 kg in the last three months) (P = 0.033).

Short-term outcomes

Subsequently, we compared the SG and NSG regarding intraoperative and postoperative outcomes, the results of which demonstrated that the SG had more intraoperative blood transfusions (P = 0.035), a higher incidence of hypoalbuminemia (P = 0.022), anastomotic fistula (P = 0.027) and surgical site infection (SSI) (P = 0.037) and a longer hospital stay (P = 0.040) (Table 2). Additionally, it was revealed that SG (19, 12–92) was not significantly different from NSG (19, 12–55) regarding the number of harvested lymph nodes (Z = -0.790, P = 0.430). Since anastomotic fistula was the most terrifying complications after curative surgeries for CRC, we then compared SG and NSG regarding re-operation rate after anastomotic fistula. Of the 38 patients suffering from anastomotic fistula in SG, 12 ones underwent reoperation while 4 patients of the 12 ones in NSG suffering from anastomotic fistula had undergone reoperation.

Since 30-day mortality and 90-day mortality is the most important parameter indicating safety and quality of curative surgery, we then assessed the impacts of sarcopenia on 30-day mortality and 90-day mortality and it was revealed that SG had significantly higher 30-day mortality (P = 0.042) and 90-day mortality (P = 0.041). For the 11 patients experiencing 30-day mortality, 4 ones died due to anastomotic fistula while anastomotic fistula caused 7 deaths occurring within 90 days after surgery.

Impacts of sarcopenia on chemotherapy-related adverse effects

According to Chinese guidelines, patients with stage III CRC or stage II CRC but with high risk factors (such as LVI and PNI) should undergo chemotherapy. Then we assessed the impacts of sarcopenia on incidence of chemotherapy-related adverse effects and revealed that patients with sarcopenia were significantly more likely to suffer from anemia (P = 0.020), mucositis or stomatitis (P = 0.043) and alopecia (P = 0.024) (Table 3).

Long-term outcomes: survival analysis

The Kaplan‒Meier method was used to calculate OS and RFS. The overall five-year OS rates and five-year RFS rates were 75.8% and 72.2%, respectively. The five-year OS rate of the SG was 73.6%, while that for the NSG was 79.4%. The five-year RFS rate of the SG was 70.2%, while that for the NSG was 75.3%. Survival curves were plotted by Kaplan‒Meier analysis, revealing that the SG was associated with significantly worse OS (P = 0.016) (Fig. 2A) and RFS (P = 0.036) (Fig. 2B).

To further evaluate the impacts of sarcopenia on OS and RFS, we then performed Cox regression analysis to demonstrate whether sarcopenia independently affected OS and RFS. Initially, univariate Cox regression analysis was performed to identify factors significantly associated with OS, demonstrating that age (P = 0.003, HR = 1.448, 95% CI: 1.131–1.854), tumour location (P = 0.003, HR = 0.745, 95% CI: 0.611–0.907), tumour grading (P = 0.006, HR = 0.345, 95% CI: 0.163–0.732), histological component (P < 0.001, HR = 2.504, 95% CI: 1.778–3.526), depth of invasion (P < 0.001, HR = 1.681, 95% CI: 1.412–2.001), lymph node metastasis (P < 0.001, HR = 2.087, 95% CI: 1.799–2.422), AJCC/UICC stage (P < 0.001, HR = 2.269, 95% CI: 1.856–2.774), lymphovascular invasion (P < 0.001, HR = 3.137, 95% CI: 2.117–4.648), perineural invasion (P < 0.001, HR = 4.311, 95% CI: 2.465–7.540), adjuvant chemotherapy (P = 0.006, HR = 0.708, 95% CI: 0.553–0.906), CEA (P < 0.001, HR = 1.598, 95% CI: 1.249–2.044), CA19.9 (P < 0.001, HR = 2.024, 95% CI: 1.505–2.722) and sarcopenia (P = 0.017, HR = 1.379, 95% CI: 1.060–1.794) were significantly associated with OS (Table 4). Then, these variables that were significantly associated with OS, as proven by the univariate Cox regression analysis, were included in the multivariate Cox regression analysis to identify independent predictive factors for OS, and the multivariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that age (P < 0.001, HR = 1.622, 95% CI: 1.258–2.091), tumour location (P = 0.001, HR = 0.714, 95% CI: 0.585–0.871), histological component (P = 0.001, HR = 1.799, 95% CI: 1.263–2.561), depth of invasion (P = 0.012, HR = 1.309, 95% CI: 1.062–1.614), lymph node metastasis (P = 0.001, HR = 1.620, 95% CI: 1.231–2.131), perineural invasion (P = 0.044, HR = 1.840, 95% CI: 1.017–3.332), CA19.9 (P = 0.029, HR = 1.423, 95% CI: 1.037–1.952) and sarcopenia (P = 0.0211, HR = 1.367, 95% CI: 1.049–1.782) were independent predictive factors (Table 4).

Similarly, independent predictive factors for RFS were identified by the Cox regression analysis. Initially, univariate Cox regression was performed to identify variables significantly associated with RFS, revealing that age (P = 0.030, HR = 1.305, 95% CI: 1.026–1.659), tumour location (P = 0.008, HR = 0.774, 95% CI: 0.641–0.934), tumour grading (P = 0.009, HR = 0.390, 95% CI: 0.193–0.787), histological component (P < 0.001, HR = 2.195, 95% CI: 1.578–3.054), depth of invasion (P < 0.001, HR = 1.542, 95% CI: 1.311–1.813), lymph node metastasis (P < 0.001, HR = 2.136, 95% CI: 1.848–2.469), AJCC/UICC stage (P < 0.001, HR = 2.367, 95% CI: 1.940–2.889), lymphovascular invasion (P < 0.001, HR = 3.041, 95% CI: 2.079–4.449), perineural invasion (P < 0.001, HR = 3.878, 95% CI: 2.219–6.778), adjuvant chemotherapy (P < 0.001, HR = 0.623, 95% CI: 0.488–0.794), CEA (P < 0.001, HR = 1.617, 95% CI: 1.271–2.056), CA19.9 (P < 0.001, HR = 1.960, 95% CI: 1.460–2.631) and sarcopenia (P = 0.037, HR = 1.310, 95% CI: 1.017–1.689) were significantly associated with RFS (Table 5). Then, these variables that were significantly associated with RFS, as proven by the univariate Cox regression analysis, were included in the multivariate Cox regression analysis, revealing that age (P = 0.002, HR = 1.465, 95% CI: 1.145–1.873), tumour location (P = 0.002, HR = 0.743, 95% CI: 0.615–0.897), histological component (P = 0.015, HR = 1.536, 95% CI: 1.088–2.168), lymph node metastasis (P = 0.001, HR = 1.558, 95% CI: 1.194–2.034), CEA (P = 0.023, HR = 1.339, 95% CI: 1.041–1.722), CA19.9 (P = 0.026, HR = 1.421, 95% CI: 1.043–1.936) and sarcopenia (P = 0.045, HR = 1.299, 95% CI: 1.006–1.677) were independent predictive factors for RFS (Table 5).

Discussion

Globally, CRC remains a huge health burden with remarkable recurrence risks. Factors resulting in sarcopenia and the possible reasons why sarcopenia could significantly affect short-term and long-term outcomes of patients with colorectal cancer have not been fully investigated. It has been hypothesized that sarcopenia identified by CT could be used as a reliable but modifiable factor for postoperative complications, deaths and cancer recurrence after curative surgery. By improving the nutritional status of patients before surgery, postoperative outcomes could be significantly improved [24, 25]. Left-sided colon cancer and rectal cancer are the most common types of CRC. It is known that left-sided colon cancer and rectal cancer are different from right-sided colon cancer in terms of postoperative complications and long-term survival. However, studies solely investigating the impacts of sarcopenia on short-term and long-term outcomes of patients with left-sided colon cancer or rectal cancer remain scarce. Thus, the present study was performed to investigate whether sarcopenia significantly affects the short-term and long-term outcomes of patients with left-sided colon cancer or rectal cancer.

First, it was demonstrated that the SG had a longer hospital stay after surgery, more intraoperative blood transfusions, and higher incidence of anastomotic fistula, SSI and hypoalbuminemia. Additionally both 30-day mortality and 90-day mortality for SG were also significantly higher than those for NSG. Second, Kaplan‒Meier analysis revealed that the patients in the SG had worse long-term survival and that sarcopenia was an independent predictive factor for both OS and RFS. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is one of the few studies systematically investigating the impacts of sarcopenia on the short-term and long-term outcomes of patients with left-sided colon cancer or rectal cancer after curative surgery.

The results of this study were consistent with those of some previous studies. In fact, sarcopenia has been reported as a risk factor for patients with various cancers, such as hepatocellular carcinoma [7], gastric cancer [9], bladder cancer [10], breast cancer [11], and pancreatic cancer [25]. A series of studies have investigated the impacts of preoperative sarcopenia on the short-term and long-term outcomes of patients with CRC. Deng CY et al. reported that progressive sarcopenia after the diagnosis of CRC had a significant negative prognostic association with overall and progression-free survival [26]. According to Trejo-Avila M et al., for patients with CRC, sarcopenia was a strong predictor of increased postoperative complications and worse survival outcomes [27]. In a study by Chai VW et al., sarcopenia was an objective, available predictive factor that is superior to the current biochemical and clinical measures of nutritional and functional status in predicting complications and cancer recurrence after curative resection for CRC [28]. Xie H et al. argued that preoperative CT-assessed sarcopenia could be employed as an effective predictor of complications and long-term prognosis for patients with CRC [29]. However, to date, there are no adequate studies investigating its significance among patients with left-sided colon cancer or rectal cancer. Therefore, our study could provide more knowledge into the significance of sarcopenia in CRC.

Despite the fact that sarcopenia has been proven to be a reliable predictor of short-term and long-term outcomes of patients with CRC, the reasons why sarcopenia leads to worse short-term and long-term outcomes have not been fully clarified. Sarcopenia has been proposed as a reflection of increased metabolic activity caused by more aggressive cancer biology, systemic inflammatory reaction and muscle depletion [30], which might in part explain why sarcopenia is a predictive factor for poorer prognosis. According to Hu WH et al., sarcopenia was significantly associated with higher IL-23 concentrations, and the combination of sarcopenia and IL-23 could more efficiently predict prognosis, suggesting that IL-23 and systemic inflammation were the possible mechanisms leading to worse survival [31]. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying sarcopenia are obviously complex, and it is almost impossible for us to raise both reproducible and sound explanations for all the recorded effects, the primary reason for which is that almost all components of the innate immune system are been involved in sarcopenia, including the catecholamine-cortisol system, chemokine signalling, interferons, complement cascades, immune-competent cells and other somatic cells [32]. These components of the innate system do not independently affect the occurrence of sarcopenia but communicate with and influence each other in a web-like manner [32]. Therefore, it is not easy for us to design persistently effective methods to reverse sarcopenia. However, some strategies have been proposed. First, daily exercise was recommended since it prevents the atrophy of muscle disuse. Additionally, it was reported that daily exercise would help reduce the concentrations of inflammation markers [32]. However, exercise is not always appropriate. Therefore, other interventions should be considered. Second, dietary or intravenous nutritional supplementation could improve nutritional status and then improve sarcopenia. Third, drugs targeting the inflammatory response are being investigated. However, their efficacy and persistence need to be improved. As a methylxanthine phosphodiesterase inhibitor drug initially used to treat asthma and COPD, theophylline has been investigated in alleviating systematic inflammation and sarcopenia [32]. However, the precise mechanisms through which theophylline alleviates sarcopenia remain to be determined. It was reported that after the application of theophylline, the production of pro-inflammatory IL-1, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF was significantly reduced [32,33,34]. Despite this finding, the application of theophylline among patients with sarcopenia caused by cancer should be prudent. Apart from theophylline, other potential drugs include infliximab, corticosteroids, thalidomide and related drugs, 4-aminoquinoline drugs (chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine and amodiaquine), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, beta-adrenergic receptor blockers, statins, metformin, and hormonal treatment [32]. However, similar to theophylline, these drugs should be prudently used among patients with sarcopenia caused by cancer.

Kaplan‒Meier and Cox regression analyses demonstrated that preoperative sarcopenia was significantly associated with worse OS and RFS, which was consistent with previous studies. Dolan DR et al. reported that sarcopenia predicted worse 30-day mortality and 1-year survival [35]. According to Miyamoto Y et al., sarcopenia was a negative predictor for the survival of patients with stage I-III CRC undergoing curative surgery [13]. Furthermore, Takiguchi K et al. argued that preoperative sarcopenia was associated with prognosis and that prognosis would significantly improve after sarcopenia had been alleviated [36]. Additionally, they also reported that not only preoperative but also postoperative nutritional interventions were important for improving sarcopenia, which might thereby improve patient survival [36]. It was also reported by some other studies that short-term and long-term outcomes of patients with rectal cancer were negatively affected by sarcopenia [37,38,39,40,41,42].However, Sergei Bedrikovetski et al. reported that sarcopenia was not a predictor of poor neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy response in locally advanced rectal cancer [43]. However, most studies reported the negative impacts of sarcopenia on short-term or long-term outcomes of patients with rectal cancer. Whereas studies assessing the impacts of sarcopenia on outcomes of patients with left-sided colon cancer have not been found. More studies were needed to further investigate the impacts of sarcopenia on left-sided colon cancer or rectal cancer. Takiguchi K et al. proposed several reasons why sarcopenia led to worse survival of patients with CRC. First, improved sarcopenia might increase muscle mass and activity, and better muscle activity was associated with better survival [36]. Second, improved sarcopenia was likely to result in a better course of other diseases, such as chronic heart failure, cirrhosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [44,45,46,47]. The mortality risk due to these chronic diseases might be reduced after sarcopenia is improved. It seemed that the reduced mortality risk due to improved sarcopenia was attributable to the associations between sarcopenia and immune senescence and the fact that sarcopenia impaired cancer immunity [48,49,50]. Additionally, immunity against inflammation and the inflammatory tumour microenvironment are involved in the occurrence and progression of cancer [51,52,53]. For patients with extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, it was reported that sarcopenia negatively affected systemic and localized immune responses and led to poorer postoperative prognosis [54]. Third, sarcopenia leads to worse tolerance for various treatments, such as surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, especially when cancer recurrence occurs. Moreover, treatment intensity significantly affects prognosis after cancer recurrence [55]. However, the treatment alternatives for individual patients should be decided by the physicians in charge after the physicians consider the patient’s general status, daily activity and organ functions. Additionally, sarcopenia also affects toxicity and reactivity after chemotherapy [56, 57]. Better nutritional status and improvements in sarcopenia when chemotherapy was applied were significantly associated with a better response and fewer severe side effects. Recently, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been widely used to treat cancers. Of these ICIs, programmed death-1 (PD-1) is the common target adopted in immune therapy. It was reported in non-small cell lung cancer that patients with sarcopenia had significantly poorer responses to programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitors [58, 59]. However, so far, there have been no studies investigating the impacts of sarcopenia on the responses of patients with CRC to PD-1 inhibitors. PD-1 inhibitors are commonly used among patients with high-frequency microsatellite instability. Thus, studies investigating the associations between sarcopenia and microsatellite status and the impacts of sarcopenia on the responses of patients with CRC to PD-1 inhibitors are warranted.

However, some shortcomings of this study should be discussed. First, this study was retrospective in nature, suggesting that selection bias was not absolutely avoidable. Therefore, prospective studies are needed to further verify the findings of this study. Second, a relatively small number of patients were included in this study, warranting studies with larger sample sizes. Third, since this study utilized data from a single country, the conclusions from this study should not be directly applied to patients from other countries since patients from different countries may have different backgrounds.

Despite these shortcomings of our study, it could still provide some guidance for future clinical practice. To the best of our knowledge, our study is one of the few studies assessing the impacts of sarcopenia on the short-term and long-term results of patients undergoing curative surgery. By improving sarcopenia and nutritional status, we could thereby remarkably improve their short- and long-term outcomes after curative surgery.

Conclusion

In conclusion, preoperative sarcopenia identified on CT was an independent predictive factor for worse OS and RFS in patients with left-sided colon or rectal cancer after curative surgery. Preoperative CT scans are mandatory to assess whether sarcopenia exists since preoperative nutritional supplementation could improve short- and long-term outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PMI:

-

Psoas muscle index

- SG:

-

Sarcopenia group

- NSG:

-

Nonsarcopenia group

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- RFS:

-

Recurrence-free survival

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- MDT:

-

Multidisciplinary teamwork

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- CCI:

-

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- ICIs:

-

Immune checkpoint inhibitors; surgical site infection (SSI)

- PD-1:

-

Programmed death-1

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.

Gupta A, Gupta E, Hilsden R, et al. Preoperative malnutrition in patients with colorectal cancer. Can J Surg. 2021;64(6):E621–9.

Papadopoulou SK. Sarcopenia: A Contemporary Health Problem among Older Adult Populations. Nutrients. 2020; 12(5):1293.

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Sayer AA. Sarcopenia. Lancet. 2019;393(10191):2636–46.

Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020; 21(3):300–7 e302.

Beaudart C, Zaaria M, Pasleau F, Reginster JY, Bruyere O. Health outcomes of sarcopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1): e0169548.

Marasco G, Serenari M, Renzulli M, et al. Clinical impact of sarcopenia assessment in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing treatments. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55(10):927–43.

Chindapasirt J. Sarcopenia in cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(18):8075–7.

Kuwada K, Kuroda S, Kikuchi S, et al. Clinical Impact of sarcopenia on gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(5):2241–9.

Fukushima H, Takemura K, Suzuki H, Koga F. Impact of sarcopenia as a prognostic biomarker of bladder cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(10):2999.

Zhang XM, Dou QL, Zeng Y, Yang Y, Cheng ASK, Zhang WW. Sarcopenia as a predictor of mortality in women with breast cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):172.

Hopkins JJ, Reif RL, Bigam DL, Baracos VE, Eurich DT, Sawyer MB. The impact of muscle and adipose tissue on long-term survival in patients with stage I to III colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62(5):549–60.

Miyamoto Y, Baba Y, Sakamoto Y, et al. Sarcopenia is a negative prognostic factor after curative resection of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(8):2663–8.

Lee MS, Menter DG, Kopetz S. Right versus left colon cancer biology: integrating the consensus molecular subtypes. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(3):411–9.

Wang S, Xu X, Guan J, et al. Better survival of right-sided than left-sided stage II colon cancer: a propensity scores matching analysis based on SEER database. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2020;31(11):805–13.

Chen Y, Hou W, Zhong M, Wu B. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of colon cancer tissue revealed the reason for the worse prognosis of right-sided colon cancer and mucinous colon cancer at the protein level. Curr Oncol. 2021;28(5):3554–72.

Boccardi V, Marano L. The geriatric surgery: the importance of frailty identification beyond chronological age. Geriatrics (Basel). 2020;5(1):12.

Marano L, Carbone L, Poto GE, et al. Handgrip strength predicts length of hospital stay in an abdominal surgical setting: the role of frailty beyond age. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022;34(4):811–7.

Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):187–96.

World Medical A. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–4.

Hamaguchi Y, Kaido T, Okumura S, et al. Proposal for new diagnostic criteria for low skeletal muscle mass based on computed tomography imaging in Asian adults. Nutrition. 2016;32(11–12):1200–5.

Broughman JR, Williams GR, Deal AM, et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia in older patients with colorectal cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2015;6(6):442–5.

Baracos VE, Arribas L. Sarcopenic obesity: hidden muscle wasting and its impact for survival and complications of cancer therapy. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(suppl_2):ii1–9.

Tamagawa H, Aoyama T, Iguchi K, et al. Preoperative evaluation of skeletal muscle mass in the risk assessment for the short-term outcome of elderly colorectal cancer patients undergoing colectomy. Mol Clin Oncol. 2018;8(6):779–84.

Jalal M, Campbell JA, Wadsley J, Hopper AD. Computed tomographic sarcopenia in pancreatic cancer: further utilization to plan patient management. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2021;52(3):1183–7.

Deng CY, Lin YC, Wu JS, et al. Progressive sarcopenia in patients with colorectal cancer predicts survival. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018;210(3):526–32.

Trejo-Avila M, Bozada-Gutierrez K, Valenzuela-Salazar C, Herrera-Esquivel J, Moreno-Portillo M. Sarcopenia predicts worse postoperative outcomes and decreased survival rates in patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36(6):1077–96.

Chai VW, Chia M, Cocco A, Bhamidipaty M, D’Souza B. Sarcopenia is a strong predictive factor of clinical and oncological outcomes following curative colorectal cancer resection. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91(5):E292–7.

Xie H, Wei L, Liu M, Yuan G, Tang S, Gan J. Preoperative computed tomography-assessed sarcopenia as a predictor of complications and long-term prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2021;406(6):1775–88.

Dodson S, Baracos VE, Jatoi A, et al. Muscle wasting in cancer cachexia: clinical implications, diagnosis, and emerging treatment strategies. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:265–79.

Hu WH, Chang CD, Liu TT, et al. Association of sarcopenia and expression of interleukin-23 in colorectal cancer survival. Clin Nutr. 2021;40(10):5322–6.

Allen SC. Systemic inflammation in the genesis of frailty and sarcopenia: an overview of the preventative and therapeutic role of exercise and the potential for drug treatments. Geriatrics (Basel). 2017;2(1):6.

Neuner P, Klosner G, Schauer E, et al. Pentoxifylline in vivo down-regulates the release of IL-1 beta, IL-6, IL-8 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Immunology. 1994;83(2):262–7.

Mascali JJ, Cvietusa P, Negri J, Borish L. Anti-inflammatory effects of theophylline: modulation of cytokine production. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1996;77(1):34–8.

Dolan DR, Knight KA, Maguire S, Moug SJ. The relationship between sarcopenia and survival at 1 year in patients having elective colorectal cancer surgery. Tech Coloproctol. 2019;23(9):877–85.

Takiguchi K, Furuya S, Sudo M, et al. Prognostic effect of sarcopenia in colorectal cancer recurrence. Nutrition. 2021;91–92: 111362.

Abe S, Kawai K, Nozawa H, et al. Preoperative sarcopenia is a poor prognostic factor in lower rectal cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy: a retrospective study. Int J Clin Oncol. 2022;27(1):141–53.

Choi MH, Oh SN, Lee IK, Oh ST, Won DD. Sarcopenia is negatively associated with long-term outcomes in locally advanced rectal cancer. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2018;9(1):53–9.

Jochum SB, Kistner M, Wood EH, et al. Is sarcopenia a better predictor of complications than body mass index? Sarcopenia and surgical outcomes in patients with rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2019;21(12):1372–8.

Chen WZ, Chen XD, Ma LL, et al. Impact of visceral obesity and sarcopenia on short-term outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(6):1620–30.

van Kooten RT, Ravensbergen CJ, van Buseck SCD, et al. Computed tomography-based preoperative muscle measurements as prognostic factors for anastomotic leakage following oncological sigmoid and rectal resections. J Surg Oncol. 2023;127(5):823–30.

Giani A, Famularo S, Fogliati A, et al. Skeletal muscle wasting and long-term prognosis in patients undergoing rectal cancer surgery without neoadjuvant therapy. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20(1):51.

Bedrikovetski S, Traeger L, Vather R, Sammour T, Moore JW. Does sarcopenia predict local response rates after chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer? Dis Colon Rectum. 2023;66(7):965–72.

Onoue Y, Izumiya Y, Hanatani S, et al. A simple sarcopenia screening test predicts future adverse events in patients with heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2016;215:301–6.

Jones SE, Maddocks M, Kon SS, et al. Sarcopenia in COPD: prevalence, clinical correlates and response to pulmonary rehabilitation. Thorax. 2015;70(3):213–8.

Hanai T, Shiraki M, Nishimura K, et al. Sarcopenia impairs prognosis of patients with liver cirrhosis. Nutrition. 2015;31(1):193–9.

Ebadi M, Bhanji RA, Mazurak VC, Montano-Loza AJ. Sarcopenia in cirrhosis: from pathogenesis to interventions. J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(10):845–59.

Nelke C, Dziewas R, Minnerup J, Meuth SG, Ruck T. Skeletal muscle as potential central link between sarcopenia and immune senescence. EBioMedicine. 2019;49:381–8.

Lutz CT, Quinn LS. Sarcopenia, obesity, and natural killer cell immune senescence in aging: altered cytokine levels as a common mechanism. Aging (Albany NY). 2012;4(8):535–46.

Zhang X, Li H, He M, Wang J, Wu Y, Li Y. Immune system and sarcopenia: presented relationship and future perspective. Exp Gerontol. 2022;164: 111823.

Greten FR, Grivennikov SI. Inflammation and cancer: triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity. 2019;51(1):27–41.

Diakos CI, Charles KA, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(11):e493–503.

Zhang X, Meng X, Chen Y, Leng SX, Zhang H. The biology of aging and cancer: frailty, inflammation, and immunity. Cancer J. 2017;23(4):201–5.

Kitano Y, Yamashita YI, Saito Y, et al. Sarcopenia affects systemic and local immune system and impacts postoperative outcome in patients with extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2019;43(9):2271–80.

Cavalli-Bjorkman N, Qvortrup C, Sebjornsen S, et al. Lower treatment intensity and poorer survival in metastatic colorectal cancer patients who live alone. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(1):189–94.

Davis MP, Panikkar R. Sarcopenia associated with chemotherapy and targeted agents for cancer therapy. Ann Palliat Med. 2019;8(1):86–101.

Aprile G, Basile D, Giaretta R, et al. The clinical value of nutritional care before and during active cancer treatment. Nutrients. 2021;13(4):1196.

Shiroyama T, Nagatomo I, Koyama S, et al. Impact of sarcopenia in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with PD-1 inhibitors: a preliminary retrospective study. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):2447.

Takada K, Yoneshima Y, Tanaka K, et al. Clinical impact of skeletal muscle area in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with anti-PD-1 inhibitors. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2020;146(5):1217–25.

Acknowledgements

The authors would express their appreciation to Xue Tang from Shenzhen People’s Hospital for her assistance with measuring PMIs.

Funding

The present study did not receive any financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.L. A and Z.J. Y designed this study. L.Z. L, Z.J. Y and T.L. A supervised this study. Q. L, J.B. W and W.Q. L collected the data. Q. L, Y. W and J. L performed statistical analyses in this study. Q. L, L.N. Y and Y.Q. C prepared the manuscript. T.L. A, and L.Z. L revised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final version of this study.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by The Ethics Committee, The First Affiliated Hospital, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, and all the patients included in this study provided informed consent in written form. The present study was in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki during the whole process.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Q., An, T., Wu, J. et al. The impact of sarcopenia on the outcome of patients with left-sided colon and rectal cancer after curative surgery. BMC Cancer 23, 640 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-11073-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-11073-0