Abstract

Background

A majority of prostate cancer cells are in a non-proliferating, G0 (quiescent) phase of the cell cycle and may lie dormant for years before activation into a proliferative, rapidly progressing, disease phase. Many mechanisms which influence proliferation and quiescence choices remain to be elucidated, including the role of non-coding RNAs. In this study, we investigated the role of a long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), SNHG1, on cell proliferation, quiescence, and sensitivity to docetaxel as a potential factor important in prostate cancer biology.

Methods

Publically available, anonymous, clinical data was obtained from cBioPortal for analysis. RNAi and prostate cancer cell lines were utilized to investigate SNHG1 in vitro. We measured G0 cells, DNA synthesis, and cell cycle distribution by flow cytometry. Western blotting was used to assess G2 arrest and apoptosis. These parameters were also investigated following docetaxel treatment.

Results

We discovered that in prostate cancer patients from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data set, high SNHG1 expression in localized tumors correlated with reduced progression-free survival, and in a data set of both primary and metastatic tumors, high SNHG1 expression was associated with metastatic tumors. In vitro analysis of prostate cancer cell lines showed SNHG1 expression correlated with a quiescent versus proliferative phenotype. Knockdown of SNHG1 by RNAi in PC3 and C4-2B cells resulted in an accumulation of cells in the G0 phase. After knockdown, 60.0% of PC3 cells were in G0, while control cultures had 13.2% G0. There were reciprocal decreases in G1 phase, but little impact on the proportion of cells in S and G2/M phases, depending on cell line. DNA synthesis and proliferation were largely halted- decreasing by 75% and 81% in C4-2B and PC3 cells, respectively. When cells were treated with docetaxel, SNHG1-depleted C4-2B and PC3 cells were resistant to G2 arrest, and displayed reduced apoptosis, as indicated by reduced cyclin B1 and cleaved caspase 3, suggesting SNHG1 levels may modulate drug response.

Conclusions

Overall, these results indicate SNHG1 has complex roles in prostate cancer, as it stimulates cell cycle entry and disease progression, but sensitizes cells to docetaxel treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Prostate cancer is characterized by slow progression, and seeding of metastatic sites, most commonly the bone. Clinical dormancy of metastatic prostate cancer may extend for years before reactivation and progression [1]. It is known that prostate cancer tissue contains few proliferating (Ki67+) cells [2], which may indicate a significant proportion of cells are quiescent (G0 phase). Regulation of quiescence and/or cell cycle (cellular dormancy) likely contributes to clinical dormancy and the response to treatment. However, some cases of prostate cancer proliferate rapidly and follow an aggressive course [3]. The participation of lncRNAs in regulation of cellular quiescence has been little-studied, but is not without precedent. GAS5 is a lncRNA in which high expression causes pancreatic cancer cells to enter a quiescent state and when expression decreases, cells re-enter a cycling state [4].

SNHG1 is a 1037 nt lncRNA which was originally described to be upregulated by x-rays in lymphoblastoid cells [5]. Data in prostate cancer has shown SNHG1 is regulated by dihydrotestosterone treatment, and there is a correlation between high SNHG1 expression and pathological stage, Gleason score, and time to biochemical recurrence [6]. This indicates a role in prostate cancer, which we expand on here. In neuroblastoma, high SNHG1 expression is associated with poor survival and is upregulated by MYCN amplification [7]. SNHG1 has been detected in serum and proposed as a biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma and lung cancer [8, 9]. In limited studies in non-small cell lung cancer, SNHG1 knockdown reduced proliferation [10]. SNHG1 may be part of a feedback loop with p53 through the action of miRNAs derived from the precursor SNHG1 RNA [11]. SNHG1 has also been shown to interact with the RNA-binding matrix protein, matrin-3 (MATR3) in neuroblastoma [12], and PP2A-c in bladder cancer [13]. The significance of these activities have not been determined. Further information regarding the biological activity of SNHG1 in cancer is difficult to ascertain, due to the literature being corrupted by fabrication of papers for profit [14, 15]. In fact, the current studies grew from a now retracted paper connecting SNHG1 to YAP1 [16]. While those experiments were not reproducible, we discovered SNHG1 impacted quiescence and chose to pursue those observations to result in the present work.

Cellular quiescence is a so-called “resting” state in which cells are non-dividing, but poised to re-enter the cell cycle when called to do so by external or internal stimuli [17]. Quiescent cells (compared to cycling cells) may be resistant to chemotherapy and radiation due to decreased reactive oxygen species, increased capacity to repair DNA, altered metabolism, differential gene expression, and lack of DNA synthesis/mitosis [17]. Elucidation of quiescent cell mechanisms will aid in targeting this phenotype for cancer treatment, or altering the chemotherapy resistance profile.

The biology of lncRNAs such as SNHG1 in cancer is an area that requires increased study. As we show here, SNHG1 is involved in prostate cancer outcome, and can have an outsized effect on cellular quiescence and docetaxel response. High SNHG1 expression in patient tumors was associated with decreased progression-free survival, compared to low SNHG1 expression. In prostate cancer cell lines, SNHG1 silencing inhibited DNA synthesis and arrested cells in G0. When treated with docetaxel, SNHG1-deficient cells were rescued from G2 arrest and apoptosis.

Methods

Cell culture

C4-2B (#CRL-3315), DU-145 (#HTB-81), LNCaP (#CRL-1740), and PC3 (#CRL-1435) prostate cancer cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). PNT2 (#95012613) benign prostate cells were obtained from Millipore-Sigma. The use of mVenus-p27K− mutant and mCherry-CDT1 peptide to identify G1 and G0 phases was first described in mammalian cell culture by Oki et al. [18] and then used by us in PC3 cells to form the PC3/VC line [19]. C4-2B/VR cells were constructed by transduction of a p27K−-mVenus MMLV vector and a CDT1-RFP709 Lentiviral vector (gift of L. Buttitta) into parental C4-2B cells. All cell lines were grown in RPMI 1640 (#11875135, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (#SH3039603HI, HyClone, Cytiva, Marlborough, MA) and 2 mM l-glutamine (#25030164, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were grown at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. All cell lines have been authenticated and confirmed Mycoplasma negative.

Docetaxel (DTX) was obtained from Cayman Chemical Company (#11637, Ann Arbor, MI) and dissolved in DMSO. For treatment, cells were treated with the specified concentrations of DTX for 2 d, starting the day following siRNA transfection.

In the cell proliferation experiment, daily cell counts were done on an Invitrogen Countess II instrument after initial seeding of 104 cells/well of a 24-well plate.

EdU assay

EdU (5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine) labeling and staining was carried out using a Click-iT Plus EdU Alexa Fluor 647 Flow Cytometry Kit (#C10634, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were cultured in 6-well plates at a seeding density of 5 × 105/well for C4-2B, PC3, and DU-145 cells, and 3.6 × 105/well for LNCaP cells. The following day, cells were transfected with siRNA. Two days after transfection, cells were pulse labeled with 10 μM EdU for 2 h, then trypsinized (#25200114, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific), washed with 0.5% BSA in PBS, fixed in 100 μl 0.9% NaCl, 1 ml ice cold methanol, and stored at -20 °C. Following a wash with 0.5% BSA in PBS, the Click-iT EdU reaction was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Co-staining with propidium iodide was then done as described below and the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting

Five hundred thousand cells were seeded into a 6-well plate the day before siRNA transfection. Three days after transfection, and following DTX treatment, cells were lysed inside the wells with RIPA buffer (#89900) containing 1:100 Halt Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail and 1:100 0.5 M EDTA (#784400), and scraping with a cell scraper (reagents all Pierce, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Lysates were sonicated with a probe sonicator and centrifuged at 17,200 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Protein concentration of supernatants were determined by BCA Assay (#23227, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Samples were prepped for SDS-PAGE by adding 4 × Laemmli Sample Buffer (#161–0747, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) containing 10% β-mercaptoethanol to 20 μg of protein and heating at 85 °C for 10 min. Samples were run on a 4-15% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Stain-Free precast gel (#4568083, Bio-Rad) and transferred to PVDF. Membrane was blocked in EveryBlot Blocking Buffer (#12010020, Bio-Rad) for 20 min., then incubated in primary antibody diluted in EveryBlot overnight at 4 °C. Blot was then washed 3 × in Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.4, 0.05% Tween-20 (TBS/T). Blot was incubated in secondary antibody diluted in EveryBlot for 1 h at room temperature and washed 3 × in TBS/T. Proteins were visualized with Supersignal West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent substrate (#34580, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Some blots were stripped with Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (#21059, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and reprobed with additional antibodies following blocking, as above. Images were taken with a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc Touch Gel Imaging System and quantified with Bio-Rad Image Lab 6.1 software.

Antibodies used in these studies are as follows: anti-β-actin (clone 13E5, #4970S), anti-caspase 3 (clone 3G2, #9668S), anti-PARP (#9542S), all rabbit monoclonals, and anti-cyclin B1 (clone V152, #4135S), a mouse monoclonal (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Anti-β-actin and anti-cyclin B1 antibodies were used at 1:2000 dilution, other primary antibodies at 1:1000. Secondary antibodies were anti-mouse IgG-HRP (#7076S) used at 1:2000 dilution, and anti-rabbit IgG1-HRP (#7074S) used at 1:3000 dilution (Cell Signaling Technology).

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was done at the Microscopy, Imaging and Cytometry Resources Core at Wayne State University, School of Medicine. EdU-Alexa Fluor 647 × PI dual stained cells, PI-only stained cells for cell cycle analysis, and C4-2B/VR cells were analyzed on a Cytek Biosciences Northern Lights instrument. PC3/VC cells were analyzed on a Becton-Dickinson LSR II instrument. Compensation controls consisted of parental PC3 cells labeled with anti-human HLA-A, B, C-FITC (#311404) and anti-human HLA-A, B, C-PE/Dazzle 594 (#311440) antibodies (Biolegend). All viable cell analyses included the addition of dapi for gating out dead cells. Data was analyzed using FlowJo v10.8.0 software (FlowJo, Ashland, OR). Final dot plots or histograms were obtained after gating on the main population from side scatter-forward scatter, plus singlets, minus dead cells.

PC3/VC cells from a confluent plate were split 1/5 to achieve a low density. The next day, media was replaced with serum-free OptiMEM (#31985070, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Then the following day, cells were trypsinized, washed in PBS containing 2% FBS, and sorted on a Sony SH800 Cell Sorter into complete RPMI media. Cells were then centrifuged, and Qiagen RNeasy lysis buffer was added to the cell pellet for subsequent RNA isolation.

RT-qPCR

RNA was isolated from cells using an RNeasy Mini-Prep kit (#74106, Qiagen, Germantown, MD). RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a SuperScript IV First Strand Synthesis System (#18090010, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was done using a TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (#4369016, Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the following TaqMan Gene Expression Assays: SNHG1 (Hs00411543), ACTB (Hs99999903_m1), and GAPDH (Hs99999905_m1). SNHG1 expression was determined relative to the housekeeping genes ACTB and GAPDH. PCR was performed on a Bio-Rad CFX Connect Real Time PCR machine.

RNAi

Cells were seeded into 24-well (105 cells) or 6-well (5 × 105 cells) the day before siRNA transfection. The day of transfection, media was replaced with OptiMEM and siRNA was combined with Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (#13778150, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and added to each well according to the manufacturer’s instructions. If cells were not harvested the next day, the OptiMEM was replaced with complete RPMI for the duration of the experiment.

Cell cycle

We seeded 2.5 × 105 C4-2B, DU-145, or PC3 cells, or 5 × 105 LNCaP cells, into 6-well plates the day before siRNA transfection. The day after transfection, media was replaced with complete RPMI. Cells were treated with 0 or 20 nM DTX for 2 d as described above. Then cells were trypsinized and washed with PBS containing 0.5% BSA. Cells were centrifuged and pellets resuspended in 100 μl cold 0.9% NaCl. Then, 1 ml ice cold 100% methanol was added to fix the cells. The day of flow cytometry, cells were washed with 0.5% BSA, PBS and resuspended in FxCycle PI/RNase Staining Solution according to the manufacturer’s instructions (#F10797, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data was analyzed using FlowJo software to determine the proportion of apoptotic cells, and the proportion in G1, S, and G2/M phases using the cell cycle tool and Watson model within the software.

For discrimination of G0 cells from other phases, live cell flow cytometry on PC3/VC or C4-2B/VR cells was performed, with dual positive (p27K−-mVenus x CDT1-mCherry or p27K−-mVenus x CDT1-RFP709) cells indicating G0 phase, single positive CDT1-mCherry or CDT1-RFP709 indicating G1, and dual negative cells comprised of S, G2, and M phases.

Docetaxel IC50 determinations

We plated 5,000 cells of each cell line (C4-2B, PC3, LNCaP, 22Rv1, and DU-145) into wells of a 96-well plate. The day after plating, we added 0, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, or 20 μM docetaxel to quadruplicate wells. Cell were incubated 5 days and proliferation was determined using a CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (#G3580, Promega, Madison, Wisconsin). Data was graphed in Graphpad Prism using an inhibitor versus response (3 parameters) model, which determined IC50 values.

Clinical data analysis

The TCGA Prostate Adenocarcinoma cohort with 494 patients (PanCancer Atlas) was utilized to assess the relationship of SNHG1 expression and patient outcomes. The mRNA expression was batch normalized from illumine HiSeq_RNASeqV2 prior to release on cBioPortal. SNHG1 expression was stratified into two groups, high and low, at the median of expression values. Patient progression free survival (PFS) was estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method. Death without tumor progression was censored at time of death. As a total of four death events out of 494 patients (< 1%) occurred without tumor progression, competing risk analysis was not performed. Relationship between the SNHG1 high/low expression and PFS was modeled with Cox multivariable regression, adjusted for age, stage, and tumor burden. Other clinical variables such as race had 68% missing values, which will not generate meaningful statistics, and were not included in the model. R (version 4.1.0) was used for statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis for non-clinical data was done using Graphpad Prism (v8.4.2) software (Graphpad Software, LLC, San Diego, CA). Paired or unpaired Student t test (as appropriate) was used as indicated in Figure legends. An exponential growth equation was used to fit cell count data. Some clinical data was analyzed using a Chi-squared test, or unpaired Student t test, as indicated. A Deming model II linear regression was used to fit data in Fig. 8.

Results

Clinical correlates of SNHG1 expression

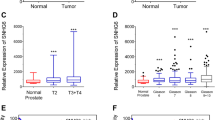

We utilized publically available clinical data with no personally identifiable information (N = 494) from cBioPortal [20, 21] to investigate SNHG1 association with clinical features of prostate cancer. When we compared PFS in the TCGA dataset (N = 493, due to one patient missing SNHG1) [22] between the low and high SNHG1-expressing groups, we found that SNHG1 was an independent prognostic factor for PFS, adjusted for age at diagnosis, stage, and tumor burden, with an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of 1.97 (P = 0.0024; Fig. 1A).

High SNHG1 expression correlates with reduced PFS and a metastatic phenotype. A PFS stratified by SNHG1 high/low expression in the TCGA prostate adenocarcinoma PanCancer Atlas data set. Median PFS was estimated with Kaplan-Meier method. Adjusted HR was estimated with the multivariable Cox model adjusted for age, stage, and tumor burden. B SNHG1 expression in primary and metastatic tumors from patients in the MSKCC data set. Line is mean, N = 122. Statistical analysis by Student’s t test: P = 0.0003. C Comparison of the number of patients with ‘altered’ SNHG1 expression in primary and metastatic tumors, from the MSKCC data set. Statistical analysis by Chi-squared test: P = 0.0003

We next compared primary versus metastatic tumors from 126 patients in the MSKCC dataset [23]. Metastatic tumors showed higher SNHG1 expression than primary tumors (P = 0.0003; Fig. 1B). Among the 22% of samples with altered SNHG1 levels in the dataset, all but one showed SNHG1 overexpression. The proportion of altered (over- or under-expression) SNHG1 in primary versus metastatic tumors was also analyzed. In primary tumors, 17% showed altered SNHG1, however, in metastatic tumors, the proportion of altered SNHG1 was 58% (P = 0.0003; Fig. 1C).

These data show that SNHG1 expression plays a role in prostate cancer progression and overexpression associates negatively with outcome. In addition, SNHG1 overexpression is more commonly associated with metastatic tumors, suggesting a contribution to metastasis biology.

Effect of SNHG1 on proliferation

A limited study of non-small cell lung cancer showed that SNHG1 knockdown resulted in reduced proliferation [10]. To assess the impact of SNHG1 on proliferation in prostate cancer cells, we performed SNHG1 RNAi in p53 (TP53) null PC3 cells, and p53 wild-type C4-2B cells and measured cell counts over 7 d. Wild type and null p53 status cells were chosen because of the effect of p53 on cancer cell biology and cell cycle, and we wanted to consider the possibility that knockdown of SNHG1 might have differential effects based on p53 status. We used two different SNHG1 siRNAs to achieve knockdown in PC3 cells of 51-64% and 24-43% using siSNHG1 #1 and siSNHG1 #2, respectively. In C4-2B cells, we achieved 54-74% and 41-52% knockdown using siSNHG1 #1 and siSNHG1 #2, respectively (Fig. 2A). A modest knockdown of 32% continued at 7 d after transfection (not shown). PC3 cells undergoing SNHG1 RNAi ceased to proliferate, or had a doubling time of 25 d, using siSNHG1 #1 or siSNHG1 #2 siRNAs, respectively, while respective control cells had a doubling time of 2.0 d and 1.8 d (Fig. 2B). Likewise, control C4-2B cells had a doubling time of 1.8 d or 2.6 d, but after SNHG1 knockdown, cell proliferation slowed and the doubling time increased to 3.7 d and 279 d, using siSNHG1 #1 and siSNHG1 #2, respectively (Fig. 2B).

SNHG1 knockdown suppresses cell proliferation. A Using RT-qPCR, SNHG1 expression was assessed for 3 d following transfection with siRNAs #1 and #2 targeting SNHG1 in PC3 and C4-2B cells, relative to control siRNA-transfected cells. B PC3 and C4-2B cells were transfected with siCTRL, siSNHG1 #1, or siSNHG1 #2 siRNA, and counted for up to 7 d. Data was fit to an exponential growth curve. C Photographs of C4-2B and PC3 cells 2d after SNHG1 knockdown. All data points represent mean ± SD with N = 3–6. All statistical analysis done using Student’s t test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001

Analysis of cell morphology after SNHG1 knockdown revealed no difference between siCTRL and siSNHG1 transfected C4-2B and PC3 cells (Fig. 2C). There were no obvious indications of toxicity, change in epithelial phenotype, attachment, granularity, or changes associated with senescence. A senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity assay was negative for senescence (not shown).

Since proliferation was reduced or eliminated after SNHG1 silencing, we next investigated whether DNA synthesis was affected in C4-2B and PC3 cells, and the benign prostate cell line, PNT2. Analysis of DNA synthesis by EdU labeling 2 d after siRNA transfection showed a substantial decrease in the proportion of EdU-labeled cells in both cancer cell lines (Fig. 3B). C4-2B transfected with siCTRL had an average of 24% EdU+ cells while silencing of SNHG1 resulted in 6.0% EdU+ cells (P < 0.03; Fig. 3C). Silencing SNHG1 in PC3 cells caused the proportion of EdU+ cells to go from 32% to 6.1% (P < 0.03; Fig. 3C). Equivalent results were obtained with DU-145 and LNCaP cells (Additional file 1). We then investigated DNA synthesis in PNT2 cells. SNHG1 knockdown efficiency of 46-67% was obtained (Fig. 3A). We found there was little effect on DNA synthesis following SNHG1 knockdown, with controls cells having 37% EdU+ cells and SNHG1-deficient cells having 30% EdU+ cells (Fig. 3B, C).

SNHG1 knockdown reduces DNA synthesis in cancer cells. A RNAi efficiency of siSNHG1 #1 siRNA was assessed in PNT2 cells by RT-qPCR. B Representative flow cytometry density plots of C4-2B, PC3, and PNT2 cells analyzed by flow cytometry following transfection with siCTRL or siSNHG1 siRNA, and a pulse with EdU to determine ongoing DNA synthesis. C Quantitation of cells labeled with EdU and analyzed by flow cytometry for DNA synthesis. C4-2B and PC3 data represent mean ± SD. N = 3. Statistical analysis done using Student’s t test: *, P < 0.05. PNT2 data represent N = 1–2

These data show that knockdown of SNHG1 halted, or nearly halted, prostate cancer proliferation independent of p53. DNA synthesis was dramatically reduced under conditions of incomplete SNHG1 knockdown. The effect was not observed in benign prostate cells.

SNHG1 RNAi induces quiescence

Since cell proliferation and DNA synthesis were reduced, we investigated whether cells had shifted into a quiescent, G0 state. To accomplish this, we utilized PC3/VC cells containing fluorescent protein markers mVenus and mCherry to indicate endogenous p27 (CDKN1B) and CDT1 (FUCCI cell system) expression, respectively, and C4-2B/VR cells containing mVenus and RFP709 to indicate p27 and CDT1 expression, respectively [18, 23]. CDT1 is expressed in G1 and G0 cells, while p27 is expressed in G0 cells. In PC3/VC cells undergoing SNHG1 silencing, there was a large shift of cells into G0 phase, from as few as 9.09% in control cells to 76.6% following SNHG1 knockdown with siSNHG1 #1 siRNA (Fig. 4A). Using a second siRNA (siSNHG1 #2), the percentage of G0 cells increased to 31.5%, indicating the effect was specific (Fig. 4A). The smaller increase in G0 cells was likely due to the reduced knockdown efficiency of siSNHG1 #2 (Fig. 2A). The average percentage of G0 in cells transfected with siSNHG1 #1 was 60.0%, while control cells had an average of 13.2% in the G0 phase, a 5.1-fold increase (P = 0.048; Fig. 4B). Using siSNHG1 #2, we similarly found the average proportion of G0 cells to increase from 8.8% in siCTRL to 31.9% in siSNHG1 #2, a 3.6-fold increase (P < 0001; Fig. 4B). In C4-2B/VR cells, SNHG1 silencing caused an increase in G0 cells from an average 49.6% in siCTRL cells to 81.7% and 75.0% in cells transfected with siSNHG1 #1 and siSNHG1 #2, respectively (P < 0.001, Fig. 4C, D).

SNHG1-deficient cells accumulate in G0 phase. A Representative flow cytometry density plots of PC3/VC cells following SNHG1 knockdown, or not (siCTRL), with two different siRNAs, siSNHG1 #1 and #2. B The proportion of G0 cells in siCTRL, siSNHG1 #1, or siSNHG1 #2-transfected PC3/VC cells. C Representative flow cytometry histograms of C4-2B/VR cells following SNHG1 knockdown with siSNHG1 #1 and #2 siRNA. D The proportion of G0 cells in siCTRL, siSNHG1 #1, or siSNHG1 #2-transfected C4-2B/VR cells. All graphed data represent mean ± SD, N = 3-6. All statistical analysis done using Student t test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001

While a significant proportion of SNHG1 depleted cells were found to be in G0 phase, the lack of DNA synthesis and cell growth suggested there may be effects on other cell cycle phases, or an increase in apoptosis. We analyzed apoptosis and cell cycle using PI staining and flow cytometry. We found the cell cycle distribution (G0/G1, S, or G2/M) between control and SNHG1 knockdown cells to be the same in C4-2B cells (Fig. 6A, B). Apoptosis was 1.0% or less in control cells, with no significant difference following SNHG1 knockdown (Fig. 6B). Similar data were obtained with DU-145 and LNCaP cells (Additional file 2). LNCaP and DU-145 cells showed a small decrease in S and G2/M phase cells following knockdown that, in some cases, reached statistical significance (Additional file 2). We could not quantify cell cycle distribution by PI in PC3 cells due to excessive polyploidy. However, histogram traces seemed to indicate some reduction in G2 cells after SNHG1 silencing (Fig. 6A).

Since knockdown of SNHG1 led to accumulation of cells in G0, we postulated that SNHG1 expression may be lower in quiescent cells, and higher in cycling cells under normal culture conditions. To investigate this, we plated PC3/VC cells for 2 d and then FACS-sorted them based on the p27K−-mVenus and CDT1-mCherry markers into G0, G1, and S/G2/M populations (Fig. 5A). We then quantified SNHG1 levels by RT-qPCR and found that the G0 population expressed 44% lower levels of SNHG1 than the G1 population (P = 0.031, Fig. 5B). Expression in the S/G2/M population was similar to G1, with 3% lower expression.

Quiescent cells express low SNHG1. PC3/VC cells were FACS sorted into G0, G1, and S/G2/M populations. A Representative flow cytometry dot plot showing the gates used in sorting populations for subsequent RT-qPCR. B Sorted cells were subjected to RT-qPCR to quantify SNHG1 levels. Data represent mean ± SD, N = 4. Statistical analysis done using Student t test: *, P < 0.05

Overall, these data show that SNHG1 expression is associated with a proliferation phenotype and that loss of SNHG1 results in accumulation of cells in a quiescent, G0 state. Knockdown of SNHG1 in multiple prostate cancer cell lines prevented cells from exiting G0, or suppressed cycling cells such that they entered G0, as determined by expression of the quiescent cell marker p27. Cell cycle analysis showed small disruptions in S and G2/M populations according to DNA content, following SNHG1 knockdown.

Effect of SNHG1 on cell cycle and docetaxel response

Docetaxel is used to treat metastatic prostate cancer and exerts its activity through stabilization of microtubules and induction of BCL-2 phosphorylation, resulting in G2/M arrest, mitotic catastrophe, and apoptosis [24]. SNHG1 expression is associated with cell cycle progression. We thus investigated the impact of SNHG1 on cell cycle and apoptosis responses to docetaxel treatment in vitro.

Treatment of C4-2B and PC3 cells with 20 nM docetaxel for 2 d led to a G2 arrest and an increase in apoptosis (Fig. 6A). However, when SNHG1 was silenced by RNAi, the G2 arrest was significantly decreased, and apoptosis showed a trend toward reduction. The increase in G0/G1 in treated SNHG1-knockdown cells compared to treated control cells was significant, as was the reduction in the G2/M population (Fig. 6B), indicating that knockdown of SNHG1 abrogated the docetaxel-mediated G2 arrest. We quantified cell cycle phase in C4-2B, but not PC3 cells because PC3 cells contain a significant number of multi-nucleated and polyploid cells, confounding cell cycle quantitation by DNA content. However, similar results were obtained in LNCaP and DU-145 cells (Additional file 2). In some cases, the docetaxel-induced G2/M arrest was almost completely negated. After docetaxel treatment, the proportion of G2/M cells in siCTRL-transfected C4-2B increased from 9.7% to 37.7% (P < 0.03; Fig. 6B). Silencing of SNHG1, however, abrogated this increase, with 23.0% in C4-2B cells (P < 0.05, compared to treated siCTRL; Fig. 6B). PC3 cells also clearly showed a reduction in the size of the 8N G2 peak. Changes in the G2/M population were reflected in changes in the G0/G1 population. The proportion of G0/G1 cells in untreated siCTRL, treated siCTRL, and treated siSNHG1 C4-2B was 63.0%, 31.7%, and 53.8%, respectively, indicating a near return to normal levels of G0/G1 after SNHG1 silencing (Fig. 6B). Similar results were obtained in DU-145 and LNCaP cells (Additional file 2). Apoptosis was reduced in treated siSNHG1 cells, compared to treated siCTRL, however, the decrease was not statistically significant in this assay. PC3 cells show what appears to be a large reduction in apparent apoptotic cells according to the PI histograms.

SNHG1 silencing is protective against DTX. We treated C4-2B and PC3 cells with DTX and analyzed changes in cell cycle and apoptosis. A Representative histograms of PI-stained cells with or without SNHG1 knockdown and with or without treatment with 20 nM DTX. B Results of quantitation of apoptotic, G0/G1, S, and G2/M populations in untreated or DTX treated, SNHG1 silenced or not, C4-2B cells. Data represent mean ± SD, N = 3-4. Statistical analysis was done using Student’s t test: ns, not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01

We then performed Western blots on PC3 and C4-2B cells to further analyze G2 phase effects and apoptosis due to docetaxel. Expression of the G2 marker, cyclin B1, increased with increasing dose of docetaxel in siCTRL for both cell lines, signifying a G2 arrest in response to drug (Fig. 7). After SNHG1 knockdown, the level of cyclin B1 decreased, with 0.20 and 0.36 as much as siCTRL in 50 nM docetaxel treated PC3 and 20 nM docetaxel treated C4-2B, respectively. Apoptosis was reduced in treated cells undergoing SNHG1 silencing (Fig. 7). Caspase 3 cleavage became evident at 50 nM and 20 nM docetaxel in siCTRL PC3 and C4-2B. Following SNHG1 knockdown, the degree of caspase 3 cleavage decreased in response to docetaxel, with 0.58 and 0.21 as much observed than in siCTRL PC3 and C4-2B, respectively (Fig. 7). We obtained similar results in DU-145 (Additional file 3), and observed reduced PARP1 cleavage in C4-2B and DU-145 (Additional files 3 and 4) Thus, apoptosis is decreased in docetaxel treated cells deficient in SNHG1.

SNHG1 silencing results in reduced G2 phase and apoptosis markers after DTX treatment. Representative Western blots showing the apoptosis marker, cleaved caspase 3, and the G2 marker, cyclin B1. β-actin is loading control. For PC3, two separate blots are shown. For C4-2B, a single blot was probed for multiple proteins. Numbers indicate band density versus siCTRL, normalized to β-actin. Full length blots are presented in Additional file 3

These data show that eliminating the activity of SNHG1 protects cells from the cell cycle effects of docetaxel, and may reduce cytotoxicity. When SNHG1 is present, cells treated with docetaxel display a G2 arrest and increased apoptosis. When SNHG1 levels are suppressed by RNAi, the G2 arrest is eliminated and apoptosis is decreased.

Correlation between SNHG1 levels and docetaxel sensitivity

We determined endogenous SNHG1 levels in a panel of prostate cancer cell lines and correlated expression to measured docetaxel IC50 values (Fig. 8). We found SNHG1 levels between the lowest (22Rv1) and highest (C4-2B) expressing cell line to vary by as much as 2.5-fold. There was a small, but statistically significant, inverse correlation between SNHG1 expression and docetaxel IC50 (P = 0.035; Deming model II regression). This supports the hypothesis that increased SNHG1 expression leads to increased sensitivity to docetaxel.

Discussion

Here we observe and characterize the biological effects of SNHG1 on prostate cancer cells through selectively suppressing its expression using RNAi. The data show that SNHG1 is involved in cell cycle and proliferation, partly through blocking G0 entry. When SNHG1 is suppressed, even incompletely, cells reduce or cease proliferation, reduce or cease DNA synthesis, and accumulate in G0 phase. Meanwhile, cell cycle distribution in other phases (S, G2/M) is largely unchanged in C4-2B. Cell cycle distribution cannot be quantified by PI in PC3 cells due to polyploidy, but our supplemental data with DU-145 and LNCaP cells show similar results to C4-2B after SNHG1 silencing. Interestingly, silencing SNHG1 in benign prostate cancer cells (PNT2) has just a minor impact on DNA synthesis.

SNHG1 expression varies with cell cycle under normal culture conditions. The quiescent (G0) population expresses lower levels of SNHG1 than the G1 or S/G2/M populations, suggesting SNHG1 has a function in cycling cancer cells. Quiescent and slowly dividing cells are resistant to chemotherapy [25, 26]. SNHG1-deficient cells treated with docetaxel showed decreased apoptosis and absence of the distinctive G2 arrest that normally occurs after treatment with this drug, indicating resistance. Remarkably, these effects are observed under RNAi conditions that result in a roughly 60% SNHG1 knockdown. Furthermore, there is a small, but significant negative correlation between SNHG1 expression and docetaxel IC50 in a panel of prostate cancer cell lines, which is consistent with our data indicating reduced apoptosis after SNHG1 knockdown.

Our data is supportive of previous limited findings. You et al. [10] showed knockdown of SNHG1 results in fewer colonies in a colony assay, suggesting a role in colony formation that could be attributed to cell cycle. Wan et al. analyzed prostate cancer in the TCGA database to find results similar to ours [6]. High SNHG1 expression was associated with higher pathological stage and Gleason score, with a significantly reduced time to biochemical recurrence. These authors also found SNHG1 to be androgen responsive- levels decreased after treatment with dihydrotestosterone, and increased when the androgen receptor was silenced by RNAi. However, these authors also found SNHG1 levels to increase after dyhydrotestosterone treatment in a microarray experiment. Further investigation of this is clearly warranted, given the importance of the androgen receptor in prostate cancer progression and treatment, and that SNHG1 levels dramatically affect quiescence and cell cycle as we have shown here.

These activities we describe for SNHG1 have not previously been legitimately characterized in detail. The majority of literature on SNHG1 focuses on proposed sponging activity, where SNHG1 binds various miRNAs to affect specific gene expression. However, the literature lists interactions with at least 72 unique miRNAs, which are proposed to regulate at least 60 unique mRNAs. Many of these publications have been reported to have concerning data [27], or have been retracted, including the first report of SNHG1 sponging activity in 2016. To our knowledge, none of the SNHG1-miRNA-mRNA interactions have been confirmed by a subsequent study by any group. This body of literature follows a consistent template which we suspect to be the result of commercialized production of fictional papers for profit (paper mills) as discussed by Else et al. and J. Christopher [14, 15].

SNHG1 may exert its activity through direct RNA–protein interactions. Yang et al. used an RNA pulldown assay followed by mass spectrometry to identify proteins interacting with SNHG1 in neuroblastoma cells [12]. One protein, matrin-3, was validated by a RIP (RNA immunoprecipitation) assay using anti-matrin-3 antibody. Matrin-3 is involved in RNA splicing and processing, suggesting a role for SNHG1 in this process. SNHG1 was also found to interact with PP2A-c to promote bladder cancer invasion [13]. SNHG1 inhibited the interaction between PP2A-c and c-Jun to promote c-Jun phosphorylation and increased expression of MMP2, a protein important for cell invasion. SNHG1 also promoted autophagy, resulting in increased miR-34a instability. MiR-34a is a miRNA which binds the 3’ UTR of MMP2 mRNA. This resulted in less miRNA-mediated inhibition of MMP2 mRNA, and therefore increased MMP2 protein. Notably, there was no demonstration of direct SNHG1 binding to miR-34a, suggesting an indirect mechanism possibly related to the autophagy process.

Prostate cancer has a slow clinical course, tumors contain few proliferating (Ki67+) cells, and the disease can become dormant for decades, followed by reactivation and aggressive growth [1, 2]. The mechanism of clinical dormancy, and signals that reactivate tumors, are not thoroughly understood. Cells in G0 phase are considered quiescent, but have the ability to re-enter the cell cycle. Clinical dormancy may be the result of cells entering G0 until stimulated to restart the cell cycle, leading to recurrence. External signals from the bone microenvironment, a common site of prostate cancer metastasis, play a role in quiescence. Bone secretes factors such as TGFβ2, GDF10, and others, which induce cellular quiescence and dormancy in some prostate cancer cell lines [28, 29]. Wnt5a from the bone microenvironment also induces prostate cancer dormancy [30]. Elucidation of mechanisms promoting quiescence or re-activation, may give insight into how cells remain inactive for extended periods.

Other non-coding RNAs have been shown to affect quiescence and cell cycle through diverse mechanisms. In pancreatic cancer, the lncRNA GAS5 regulates quiescence in cancer stem cells, which by extension, affects tumor recurrence [4]. LncRNAs have been shown to be involved in trimethylation of histone H4 at lysine 20, a process associated with quiescence [31]. Our study links SNHG1 to quiescence, but the molecular basis for this activity is currently under investigation.

Conclusions

We show that SNHG1 plays a role in cell proliferation such that loss of SNHG1 blocks cell exit from G0, leading to an accumulation of quiescent cells and a cessation of cell expansion in culture. Furthermore, SNHG1 expression correlates with the quiescent versus cycling state of unmanipulated prostate cancer cells. DNA synthesis in prostate cancer, but not benign, cells virtually ceases in the absence of SNHG1. SNHG1-deficient cells resist G2 arrest when exposed to docetaxel, and the data suggest a decrease in apoptosis, indicating SNHG1 levels influence docetaxel resistance. Elucidation of the molecular mechanism of these effects is important because as we have shown, SNHG1 levels correlate with prostate cancer metastasis and impact clinical outcome. Then, targeting activities SNHG1 is involved in could play a role in prostate cancer treatment, and the biology of tumor dormancy and recurrence.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Clinical data is available from the cBioPortal repository (https://www.cbioportal.org/), specifically, the TCGA, PanCancer Atlas (https://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=prad_tcga_pan_can_atlas_2018) and MSK, Cancer Cell 2010 (https://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=prad_mskcc) datasets.

Abbreviations

- DTX:

-

Docetaxel

- EdU:

-

5-Ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- lncRNA:

-

Long non-coding RNA

- PI:

-

Propidium iodide

- RIP:

-

RNA immunoprecipitation

- TCGA:

-

The cancer genome atlas

References

Cackowski FC, Heath EI. Prostate cancer dormancy and recurrence. Cancer Lett. 2022;524:103–8.

Sadi MV, Barrack ER. Determination of growth fraction in advanced prostate cancer by Ki-67 immunostaining and its relationship to the time to tumor progression after hormonal therapy. Cancer. 1991;67(12):3065–71.

Soundararajan R, Viscuse P, Pilie P, Liu J, Logotheti S, Laberiano Fernandez C, Lorenzini D, Hoang A, Lu W, Soto LMS, et al. Genotype-to-Phenotype Associations in the Aggressive Variant Prostate Cancer Molecular Profile (AVPC-m) Components. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(13):3233.

Sharma NS, Gnamlin P, Durden B, Gupta VK, Kesh K, Garrido VT, Dudeja V, Saluja A, Banerjee S. Long non-coding RNA GAS5 acts as proliferation “brakes” in CD133+ cells responsible for tumor recurrence. Oncogenesis. 2019;8(12):68.

Chaudhry MA. Expression pattern of small nucleolar RNA host genes and long non-coding RNA in X-rays-treated lymphoblastoid cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(5):9099–110.

Wan X, Huang W, Yang S, Zhang Y, Pu H, Fu F, Huang Y, Wu H, Li T, Li Y. Identification of androgen-responsive lncRNAs as diagnostic and prognostic markers for prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(37):60503–18.

Sahu D, Hsu CL, Lin CC, Yang TW, Hsu WM, Ho SY, Juan HF, Huang HC. Co-expression analysis identifies long noncoding RNA SNHG1 as a novel predictor for event-free survival in neuroblastoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(36):58022–37.

Leng Q, Lin Y, Zhan M, Jiang F. An integromic signature for lung cancer early detection. Oncotarget. 2018;9(37):24684–92.

Kim SS, Baek GO, Son JA, Ahn HR, Yoon MK, Cho HJ, Yoon JH, Nam SW, Cheong JY, Eun JW. Early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma via liquid biopsy: panel of small extracellular vesicle-derived long noncoding RNAs identified as markers. Mol Oncol. 2021;15(10):2715–31.

You J, Fang N, Gu J, Zhang Y, Li X, Zu L, Zhou Q. Noncoding RNA small nucleolar RNA host gene 1 promote cell proliferation in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Indian J Cancer. 2014;51(Suppl 3):e99–102.

Yu F, Bracken CP, Pillman KA, Lawrence DM, Goodall GJ, Callen DF, Neilsen PM. p53 Represses the Oncogenic Sno-MiR-28 Derived from a SnoRNA. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129190.

Yang TW, Sahu D, Chang YW, Hsu CL, Hsieh CH, Huang HC, Juan HF. RNA-binding proteomics reveals MATR3 interacting with lncRNA SNHG1 to enhance neuroblastoma progression. J Proteome Res. 2019;18(1):406–16.

Xu J, Yang R, Hua X, Huang M, Tian Z, Li J, Lam HY, Jiang G, Cohen M, Huang C. lncRNA SNHG1 Promotes Basal Bladder Cancer Invasion via Interaction with PP2A Catalytic Subunit and Induction of Autophagy. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2020;21:354–66.

Else H, Van Noorden R. The fight against fake-paper factories that churn out sham science. Nature. 2021;591(7851):516–9.

Christopher J. The raw truth about paper mills. FEBS Lett. 2021;595(13):1751–7.

Gao L, Cao H, Cheng X. A positive feedback regulation between long noncoding RNA SNHG1 and YAP1 modulates growth and metastasis in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma [Retraction]. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10(11):4016.

Marescal O, Cheeseman IM. Cellular mechanisms and regulation of quiescence. Dev Cell. 2020;55(3):259–71.

Oki T, Nishimura K, Kitaura J, Togami K, Maehara A, Izawa K, Sakaue-Sawano A, Niida A, Miyano S, Aburatani H, et al. A novel cell-cycle-indicator, mVenus-p27K-, identifies quiescent cells and visualizes G0–G1 transition. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4012.

Pulianmackal AJ, Sun D, Yumoto K, Li Z, Chen YC, Patel MV, Wang Y, Yoon E, Pearson A, Yang Q, et al. Monitoring spontaneous quiescence and asynchronous proliferation-quiescence decisions in prostate cancer cells. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:728663.

Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(5):401–4.

Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6(269):pl1.

Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. The molecular taxonomy of primary prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;163(4):1011–25.

Taylor BS, Schultz N, Hieronymus H, Gopalan A, Xiao Y, Carver BS, Arora VK, Kaushik P, Cerami E, Reva B, et al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(1):11–22.

Pienta KJ. Preclinical mechanisms of action of docetaxel and docetaxel combinations in prostate cancer. Semin Oncol. 2001;28(4 Suppl 15):3–7.

Zeuner A, Francescangeli F, Contavalli P, Zapparelli G, Apuzzo T, Eramo A, Baiocchi M, De Angelis ML, Biffoni M, Sette G, et al. Elimination of quiescent/slow-proliferating cancer stem cells by Bcl-XL inhibition in non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21(12):1877–88.

Quayle LA, Ottewell PD, Holen I. Chemotherapy resistance and stemness in mitotically quiescent human breast cancer cells identified by fluorescent dye retention. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2018;35(8):831–46.

Zielske SP, Cackowski FC. Critical analysis of the hypothesized SNHG1/miR-195-5p/YAP1 axis. Funct Integr Genomics. 2022;23(1):2.

Yu-Lee LY, Lee YC, Pan J, Lin SC, Pan T, Yu G, Hawke DH, Pan BF, Lin SH. Bone secreted factors induce cellular quiescence in prostate cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):18635.

Yu-Lee LY, Yu G, Lee YC, Lin SC, Pan J, Pan T, Yu KJ, Liu B, Creighton CJ, Rodriguez-Canales J, et al. Osteoblast-secreted factors mediate dormancy of metastatic prostate cancer in the bone via activation of the TGFbetaRIII-p38MAPK-pS249/T252RB pathway. Cancer Res. 2018;78(11):2911–24.

Ren D, Dai Y, Yang Q, Zhang X, Guo W, Ye L, Huang S, Chen X, Lai Y, Du H, et al. Wnt5a induces and maintains prostate cancer cells dormancy in bone. J Exp Med. 2019;216(2):428–49.

Bierhoff H, Dammert MA, Brocks D, Dambacher S, Schotta G, Grummt I. Quiescence-induced LncRNAs trigger H4K20 trimethylation and transcriptional silencing. Mol Cell. 2014;54(4):675–82.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Program Physician Research Award (W81XWH2010394, F. Cackowski), startup funds from the Karmanos Cancer Institute (F. Cackowski), and a Michigan Prostate SPORE (P50CA186786) Career Enhancement Project award (S. Zielske). The Microscopy, Imaging and Cytometry Resources Core is supported, in part, by NIH Center grants P30 CA22453 to the Karmanos Cancer Institute and R50 CA251068-01 to Dr. Moin, Wayne State University, and the Perinatology Research Branch of the National Institutes of Child Health and Development. The Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Core is supported, in part, by NIH Center grant P30 CA022453 to the Karmanos Cancer Institute at Wayne State University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SZ: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, writing – original draft, writing-review & editing, visualization, project administration, and funding acquisition. WC: Formal analysis and writing – original draft. KI: Resources. FC: Conceptualization, writing – review & editing, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Knockdownof SNHG1reduces DNA synthesis in LNCaPand DU-145 cells. (A) Assessmentof SNHG1knockdown in LNCaPand DU-145 cells. (B) Flow cytometryplot of EdUlabeled cells with or without SNHG1knockdown. (C) Quantitationof the proportion of EdU+cells after transfection with siCTRLor siSNHG1.All graphs depict mean±SD, N=3. Statistical analysis done using Studentt test: *P<0.05; **, P<0.01.

Additional file 2.

SNHG1silencing is protective against DTX in LNCaPandDU-145 cells. (A) Representative histograms of PI stained LNCaPandDU-145 with or without SNHG1knockdown and with or without treatment with20 nMDTX. (B) Results of quantitation of apoptotic, G0/G1,S, and G2/Mpopulations in untreated or DTX treated, SNHG1silenced or not, cells.Data represent mean ±SD, N=4. Statistical analysis was done usingStudent’s t test: ns, not significant; *P<0.05; **, P<0.01.

Additional file 3.

SNHG1silencing results in reduced G2phaseand apoptosis markers in DU-145 cells after DTX treatment. Western blotsshowing the apoptosis marker, cleaved caspase 3 and cleaved PARP1, and the G2marker,cyclin B1. β-actin is loading control. In (A), displayed is the sameblot reprobedfor different proteins. In (B), displayed are differentexposures of the same blot probed for caspase 3 (full length and cleavagefragment) and β-actin. Numbers indicate band density versus siCTRL, normalizedto β-actin.

Additional file 4.

Original,full-length images from Western blotting, corresponding to cropped images shownin Fig. 7. SNHG1silencing results in reduced G2phaseand apoptosis markers after DTX treatment. Western blots showing the apoptosismarkers, cleaved caspase 3 and cleaved PARP1, and the G2marker,cyclin B1. β-actin is loading control. For PC3 (A), two separate blotsare shown. For C4-2B (B), a single blot was probed for multipleproteins. Numbers indicate band density versus siCTRL, normalized to β-actin.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zielske, S.P., Chen, W., Ibrahim, K.G. et al. SNHG1 opposes quiescence and promotes docetaxel sensitivity in prostate cancer. BMC Cancer 23, 672 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-11006-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-11006-x