Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate prognostic significance of human papillomavirus (HPV) in hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma patients, and to investigate the effect of p53 and TP53 mutations on the prognosis of patients.

Methods

A total of 111 patients were enrolled in our retrospective study. HPV infection status was detected in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue by real-time multiplex PCR test. p53 expression was evaluate by immunohistochemical staining. TP53 exon mutations were analyzed by PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing. HPV infection status, p53 expression and TP53 mutation were compared with clinical outcome including overall survival and recurrence-free survival by Kaplan-Meier method and Log-rank test.

Results

Of the 111 investigated patients, 18 (16.22%) were positive for HPV infection. HPV(-) patients have a worse clinical outcome than HPV(+) patients. TP53 mutations have similar mutation rates in patients with and without HPV (55.56% vs. 41.94%). p53 and TP53 mutation were not associated with prognosis of patients in HPV(-) patients. TP53 disruptive mutations were found both in patients with or without HPV infection. Furthermore, TP53 non-disruptive mutation had a significantly better clinical outcome than those with disruptive mutation in HPV(-) patients.

Conclusion

Our results showed that HPV infection status is a strong prognostic indicator of survival. p53 and TP53 mutations do not appear to significantly impact survival in HPV(-) patients. TP53 disruptive mutation is associated with reduced survival in HPV(-)/TP53 mutation patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is one of the most common cancers in the world which is heterogeneous in tumor site, pathogenesis and cause with 890,000 new cases and 450,000 deaths in 2018 [1]. Hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (HPSCC) is a subtype of HNSCC, which 70% to 85% of cases are already in advanced stage when diagnosed due to the hidden location of the onset [2, 3]. The pathogenesis of HPSCC is multifactorial and is linked to smoking, alcohol consumption and infection with the human papillomavirus (HPV) [4,5,6]. Multimodality therapies, including surgery, chemotherapy, biologic therapy, and radiotherapy, particularly intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), are the current treatments for patients [7]. Despite recent advances in these treatment modalities, the overall survival remains poor over the past years.

Although HPV infection status has been identified as a risk factor in HNSCC, especially oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) [8], prognostic significance of HPV in non-OPSCC HNSCC is still disputable [9]. Li et al. showed that HPV status was the greatest factor in survival outcome between the HPV-positive and -negative cohorts at the hypopharynx subsites through a large-sample analysis [10]. However, several studied reported that HPV does not appear to significantly impact survival or disease control in HPSCC patients [11,12,13,14,15,16].

In addition, the abrogation of p53 function is one of the most common molecular alterations in HNSCC [17, 18] through the mutation of its gene, TP53 [4], the loss of heterozygosity of TP53 [6] or interaction with viral proteins [19]. The involvement of p53 in apoptosis and cell cycle control, making it a reasonable prognostic biomarker [18]. In addition, the TP53 mutation profile observed in tumor samples suggests that these mutations differ in their impact on prognosis [20, 17]. The role of p53 or TP53 as a prognostic marker of HNSCC is controversial. As compared with wild-type TP53, the presence of any TP53 mutation was associated with decreased overall survival in HNSCC patients [20]. However, the results were inconsistent for specific HNSCC subtypes. Singh et al. reported that survival of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) patients was not affected by HPV and p53 status [21]. Moreover, Hong et al. did not show any evidence that p53 mutation could modify the effect of HPV status on outcomes from their study [22]. For now, no relation between HPV infection status, TP53 mutation and prognosis of HPSCC patients is currently well established.

Herein, we sought to evaluate the effect of HPV status on HPSCC survival, to determine the incidence of TP53 mutation in HPSCC and to seek associations among TP53 status, HPV status and survival.

Methods and materials

Patient tissue and ethics approval

A cohort of 111 formalin fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) HPSCC tissues were collected from patients diagnosed with HPSCC pathologically after surgery in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Eye & ENT Hospital of Fudan University from January 2015 to January 2018. All participants provided written informed consent forms. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Eye & ENT Hospital of Fudan University (No. 2018036).

Detection of HPV genotype

Detection of HPV genotypes were analyzed by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using formalin fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) HPSCC tumor samples. Briefly, after deparaffinization and rehydration, DNA was isolated from FFPE tissue using QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR amplifications were performed in a Thermal Cycler (ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System, Life Technologies, Shanghai, China) using HPV Genotyping Real-time PCR Kit (Hybribio Limited, China) which is a real-time multiplex PCR test for the detection of 23 HPV genotypes (HPV6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 42, 43, 44, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73, 81 and 82), in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions [23, 24]. An HPV-positive tumor was defined as a tumor for which there was specific positive amplification of either HPV subtype.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining and assessment

Tumor p53 protein expression was evaluated by means of immunohistochemical analysis with a mouse monoclonal antibody (1:200, Gene Tech, Shanghai) visualized with use of BenchMark Autostainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, USA). Positive p53 expression was defined as strong and diffuse nuclear staining. All sections were graded from level 0 to level 4 according to the following assessment: level 0, less than 1% positive cells; level 1, 1-9% positive cells; level 2, 10–49% positive cells; and level 3, ≥50% positive cells. Level 0 to level 1 was defined as low expression, and level 2 to level 3 was defined as high expression. The staining results were checked independently by two senior pathologists, and the discrepancies in immunostaining reviewing were solved by consensus.

Database information

The Gene_Outcome module in TIMER2.0 (http://timer.cistrome.org/) [25] was used to evaluate the outcome significance of TP53 gene expression.

TP53 mutation analysis

DNA extracted from FFPE tissue was used to analyze mutations in the TP53 gene. Three sets of primers were used to amplify genomic DNA sequences of exons 5, 6 and 8 with the most frequent TP53 mutations (Table 1). The PCR was conducted in a 20 μl reaction mix containing 1 μl of DNA, 10 μl of PremixTaq polymerase (Vazyme), 7 μl of ddH2O, and 2 μl of primers. The thermal cycling conditions were an initial denaturation at 94 ℃ for 5 min, followed by 28 cycles of denaturation at 94 ℃ for 30 seconds, primer annealing at 58 ℃ for 30 seconds, and extension at 72 ℃ for 1 min, and then a final extension at 72 ℃ for 10 min. The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis using a 2% agarose gel. PCR products were purified with Universal DNA Purification Kit (Tiangen Biotech), and submitted to a commercial company for Sanger sequencing. Sequencing was performed using ABI 3730 XL sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Sequencing results were analyzed with DNA Sequencing analysis software, interpreted with Sequencing analysis 5.2.0 software, and compared with Sequencher 5.1 software package.

Polymorphisms and mutations were determined based on the reference sequences available from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) TP53 database (http://p53.iarc.fr). The genetic mutations were described in accordance with the nomenclature rules of the Human Genome Variation Society (http://www.HGVS.org/varnomen). The hotspot mutation of TP53 was confirmed according to the TP53 Database (R20, July 2019, https://tp53.isb-cgc.org). TP53 mutations were grouped as ‘‘disruptive’’ and ‘‘non-disruptive’’ according to available information about the functional differences of various TP53 mutations [20]. Disruptive mutations were defined as stop mutations, frameshift mutations, or nonconservative mutations occurring within the key DNA-binding domain L2/L3. All other mutations were defined as non-disruptive mutations (excluding stop codons) [26].

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS), defined as the time from diagnosis to death. Secondary end point was recurrence-free survival (RFS), defined as the time from diagnosis to death or the first documented relapse. The Chi-square test was used to compare demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 22.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), and graphed using GraphPad Prism (version 8; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). OS and RFS were evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method and Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Differences were considered significant if the p value was <0.05.

Results

Overview of main clinical features of the cohort and prevalence of HPV

Collectively, a cohort of consecutive 111 HPSCC patients was included in the current study from January 2015 to January 2018 in Eye & ENT Hospital, Fudan University. The tumors mainly originated from the pyriform sinus (n=97, 87.39%), followed by the postcricoid region (n=7, 6.31%) and the posterior pharyngeal region (n=7, 6.31%). According to the 8th AJCC staging system, most of patients were in advanced stage (104/111, 93.69%). During the 5-year follow-up period, 36.94% (41/111) patients developed regional tumor recurrence. The 5-year OS and RFS rate of the cohort was 65.77% and 63.06%, respectively. The mean OS time and RFS time was 40.85±17.40 and 37.36±19.59 months, respectively.

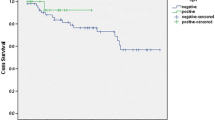

Of the 111 investigated patients, 18 (16.22%) were positive for HPV infection (all types combined). Among them, HPV16 was the most prevalent subtype which accounted for 77.78%. In addition, there was 1 case of HPV56, 6 and 82 subtype, respectively. Of note, there was 1 case of HPV81 and 58 subtype double infection. By using Kaplan-Meier method, although it did not reach statistical significance, HPV(+) HPSCC patients had better OS than those of the HPV(-) patients (88.89 % vs 61.29%, p=0.0741, Fig. 1A). Furthermore, HPV(+) HPSCC patients had significant better RFS than those of the HPV(-) patients (88.89 % vs 58.06%, p=0.0353, Fig. 1B).

Prognostic significance of HPV infection status in 111 advanced HPSCC patients Kaplan-Meier estimates of (A) OS and (B) RFS among the 18 HPV(+) HPSCC patients (of whom 2 died) and the 93 HPV(-) HPSCC patients (of whom36 died). The mean OS and RFS among HPV(+) patients were 41.06 and 39.78 years, as compared with 40.81 and 36.89 years among HPV(-) patients. p=0.0741 for OS, p=0.0353 for RFS (Log-rank test)

Prognostic significance of p53 protein and TP53 gene expression in HPV-negative advanced HPSCC

Since HPV(-) HPSCC patients have worse prognosis, we aimed to investigate whether tumor suppressor gene TP53 and its encoded p53 protein could be a prognostic indicators for HPV(-) HPSCC patients. By IHC staining, we found that most of p53 protein exist in the cellular nuclear of tumor cells, rather than in the stroma area (Fig. 2A-B). As shown in Fig. 2C-D, the results showed no statistical difference in OS and RFS between the HPV(-) patients with high and low expression of p53 protein (69.23% vs 58.14%, p=0.2771; 64.10% vs 55.81%, p=0.3715). Similarly, there was no difference in HPV(+) HPSCC patients (data not shown). Moreover, the expression level of p53 is not associated with the clinicopathologic features of HPSCC patients, regardless of HPV infection status (Table 2).

Patterns of p53 protein expression and prognostic significance of p53 protein and TP53 gene in HPV(-) advanced HPSCC patients (A) Complete absence or low expression (<50% of the tumour cells) of staining in the tumour. B Uniform strong nuclear staining in at least 50% of the tumour cells. Scale bar: 100 μm. Kaplan-Meier estimates of (C) OS and (D) RFS among the 39 HPSCC patients with HPV(-)/p53high (of whom 12 died) and the 43 HPSCC patients with HPV(-)/p53low (of whom 18 died). The mean OS and RFS among patients with HPV(-)/p53high were 44.46 and 41.33 years, as compared with 39.86 and 35.63 years among patients with HPV(-)/p53low. p=0.2771 for OS, p=0.3715 for RFS (Log-rank test). Eleven patients did not undergo IHC staining due to sample reasons. E Kaplan-Meier curves shows outcome significance of TP53 gene expression among 522 head and neck cancer (HR=0.97, p=0.632). F Kaplan-Meier curves shows outcome significance of TP53 gene expression among 98 HPV(+) head and neck cancer (HR=0.65, p=0.0157). G Kaplan-Meier curves shows outcome significance of TP53 gene expression among 422 HPV(-) head and neck cancer (HR=1.04, p=0.555). Data available from Gene_Outcome module in TIMER2.0 (http://timer.cistrome.org/)

Then, we aimed to evaluate the outcome significance of TP53 gene in head and neck cancer by online database analysis which is performed by Cox proportional hazard model (Fig. 2E-G). We found that the expression of TP53 is not an indicator of prognosis in total HNSCC and HPV(-) HNSCC patients (HR=0.97, p=0.632; HR=1.04, p=0.555), but is significant only in HPV(+) patients (HR=0.65, p=0.0157).

Distribution and prognostic significance of TP53 mutation in HPV-negative advanced HPSCC

Due to frequent mutation of TP53 in HNSCC patients, we then aimed to estimate the outcome significance of TP53 exon mutation. It was found that 41.94% (39/93) HPV(-) HPSCC patients had TP53 exon mutation (Fig. 3A). Among them, exon 5 had the most mutation events (21.11%), followed by exon 8 and exon 6 (17.78% and 13.33%). The mutation of any TP53 exon was defined as TP53 mutation, and we evaluated the significance of TP53 mutation for the prognosis of patients. However, there was no statistical difference in OS and RFS between the HPV(-) patients with wild and mutation TP53 (64.71% vs 56.41%, p=0.5798; 60.78% vs 53.85%, p=0.6264; Fig. 3B-C). Furthermore, to reduce the interference factor of index mixing, the outcome significance of every single exon mutation was evaluated. Unfortunately, not a single exon mutation was associated with prognosis in patients with HPV(-) HPSCC (p>0.05; Fig. 3D-I). Similarly, there was no difference in HPV(+) HPSCC patients (data not shown).

Distribution and prognostic significance of TP53 mutation in HPV(-) advanced HPSCC (A) Distribution of exon 5, 6 and 8 mutations of TP53. Kaplan-Meier estimates of (B) OS and (C) RFS among the 51 HPSCC patients with HPV(-)/TP53wt (of whom 18 died) and the 39 HPSCC patients with HPV(-)/TP53mut (of whom 17 died). The mean OS and RFS among patients with HPV(-)/TP53wt were 41.10 and 36.78 years, as compared with 41.95 and 38.33 years among patients with HPV(-)/TP53mut. p=0.5798 for OS, p=0.6264 for RFS (Log-rank test). Three patients did not undergo TP53 mutation detection due to sample reasons. wt, wild type; mut, mutation. OS (D-F) and RFS (G-I) of each exon among the HPV(-)HPSCC patients. E, exon

Detailed TP53 exon mutation events and its prognostic significance in HPV-negative advanced HPSCC

Altogether, 65 different types of variants (70 times) of TP53 were found in this study (Table 3), of which 47 variants have been reported as hot-spot mutations in previous studies. C:G > T:A was the most frequent pattern of substitution observed across all subject groups. Nearly half (36/70, 51.43%) of the variants were missense mutation, and 14 of 70 times (20%) resulted in stop codon. The location and amino acid changes are shown in Table 4. The most frequently found variants, detected in 111 subjects, was located at 637 codon in exon 6 resulting in a stop codon change (3 times), followed by variants at codon 452 in exon 5 (proline-to-leucine), and variants at codon 586 and 916 in exon 6 and 8 resulting in a stop codon change (2 times). The majority (36/49, 73.47%) of subjects with TP53 mutations had a mutation at only one spot, while one subject had mutations at four spots, four subjects had mutations at three spots and eight subjects had mutations at two spots (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the proportion of patients with TP53 mutation was similar among HPSCC cases with or without HPV infection (10/18, 55.56% vs. 39/93, 41.94%, p=0.2868, Fig. 5).

Distribution of TP53 exon mutation events and prognostic significance of disruptive mutation of TP53 in HPSCC patients (A) Histogram of number of cases with TP53 mutations by TP53 codon position and the top 4 most frequently mutated TP53 codons located in the DNA-binding domain in HPSCC patients. Kaplan-Meier estimates of (B) OS and (C) RFS among the 33 HPSCC patients with HPV(-)/TP53disruptive mut and the 6 HPSCC patients with HPV(-)/TP53non-disruptive mut. p=0.0492 for OS, p=0.0411 for RFS (Log-rank test)

As a transcription factor, p53 mutation in the domain of DNA binding region, which is called disruptive mutation, lead to loss of p53 protein DNA binding and gene expression regulation. We then aimed to estimate the outcome significance of disruptive mutation in HPV(-)/TP53mut HPSCC patients. As shown in Fig. 4B-C, when compared with the patients with disruptive mutation (33 cases), we found that patients without disruptive mutation (6 cases) had a significantly better OS (51.52% vs. 83.33%, p=0.0492) and RFS (48.48% vs. 83.33%, p=0.0411).

Discussion

In this current study, to address the controversial information regarding the role of HPV infection in HPSCC, the pathological tissues of 111 HPSCC patients were collected, and the relationship between HPV infection status and prognosis of HPSCC patients was proved by detecting HPV genotypes. The prognosis role of p53 in HPV(-) HPSSCC patients was also demonstrated by detecting the p53 protein content and comprehensive landscape of TP53 mutation.

First, we showed that HPV(-) HPSCC patients had worse OS and RFS than those of the HPV(+) patients, despite several reports to the contrary [11,12,13,14,15]. We speculated that this might be related to the differences in sample detection methods and the characteristics of the included population. The World Health Organization and the Union for International Cancer Control recommend the use of p16 IHC to simplify the detection of HPV infection in HNSCC, particularly in OPSCC [27, 28]. However, it is disadvantageous to use the gold standard to diagnose HPV infection in non-OPSCC HNSCC [9, 16, 29]. In this study, we performed p16 IHC staining and tried to detect HPV infection status (data not shown). However, only five of the 111 HPSCC samples were p16 positive (4.50%), and only two of them tested positive for HPV genotype detection. The harmonization of HPV testing method needs to be addressed, and the results of the analysis of different anatomical sites of HNSCC should be interpreted with caution before more large sample data are presented.

Secondly, although Hong et al. showed that HPV+ patients were significantly less likely to have p53 mutations than HPV-negative patients [22], our results showed that 41.94% (39/93) of HPV(-) HPSCC patients developed TP53 mutations, while 55.56% (10/18) of HPV(+) HPSCC patients developed TP53 mutations (p=0.287). Moreover, although previous study [30] found the significant correlation between a high expression of p53 and a histological grade of well differentiation, advanced tumor (T) and TNM stage in HPSCC patients, we found that p53 expression level, similarly like TP53 mutation, was not associated with prognosis of HPSCC patients, regardless of HPV infection status. We speculated that this is related to sample size differences and inconsistent antibodies used in IHC staining. Similar to our results, Singh et al. [21] and Hong et al. [22] found that survival of patients was not affected by p53 status. However, Ernoux-Neufcoeur et al. found that the 5-year disease-free survival rate was 73% in p53- HPSCC tissues versus 48% in p53+ HPSCC tissues[14]. This suggests that larger sample sizes and better postoperative follow-up are needed to clarify the role of controversial p53 status as an indicator of patient prognosis.

Finally, our dichotomous categorization based on protein folding and certain features of the gene classified HPV(-) patients into disruptive mutation and non-disruptive mutation groups, finding that patients with non-disruptive mutation had a significantly better OS and RFS than those with disruptive mutation. Several studies showed that the disruptive mutation is only found in HPV-negative HNSCC which suggest the absence of TP53 disruptive mutations may underlie the improved patient outcome of HPV-positive HNSCC [26, 31, 32]. However, TP53 mutations were found in 10 of the 18 HPV(+) HPSCC patients in our study, all of which were disruptive mutations. Considering the complexity of p53 interactions, the functional properties of each mutation may uniquely affect pathways for maintaining genomic integrity that involve p53. The biologic effects of TP53 mutations may also be influenced by the presence or absence of the remaining wild-type allele and by the gain of function of some mutants [20].

Overall, our results suggest that HPSCC patients without HPV have a worse clinical outcome than patients with HPV. TP53 mutations have similar mutation rates in HPSCC patients with and without HPV. Moreover, p53 and TP53 mutation were not associated with prognosis of HPSCC patients in HPV(-) HPSCC patients. TP53 disruptive mutations were found in HPSCC patients with or without HPV. Furthermore, TP53 non-disruptive mutation had a significantly better clinical outcome than those with disruptive mutation in HPV(-) HPSCC patients.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical issues, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Johnson DE, Burtness B, Leemans CR, Lui VWY, Bauman JE, Grandis JR. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):92.

Chow LQM. Head and neck cancer. N Eng J Med. 2020;382(1):60–72.

Huang Q, Ye M, Li F, Lin L, Hu C. Prognostic and clinicopathological significance of transcription factor c-Jun in hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a 3-year follow-up retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2022;22:1019.

Chaudhary S, Ganguly K, Muniyan S, et al. Immunometabolic alterations by HPV infection: new dimensions to head and neck cancer disparity. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(3):233–44.

Anna Szymonowicz K, Chen J. Biological and clinical aspects of HPV-related cancers. Cancer Biol Med. 2020;17(4):864–78.

Solomon B, Young RJ, Rischin D. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: genomics and emerging biomarkers for immunomodulatory cancer treatments. Semin Cancer Biol. 2018;52:228–40.

Lindemann A, Takahashi H, Patel AA, Osman AA, Myers JN. Targeting the DNA damage response in OSCC with TP 53 mutations. J Dent Res. 2018;97(6):635–44.

Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):24–35.

D’Souza G, Westra WH, Wang SJ, et al. Differences in the prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in head and neck squamous cell cancers by sex, race, anatomic tumor site, and HPV detection method. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(2):169.

Li H, Torabi SJ, Yarbrough WG, Mehra S, Osborn HA, Judson B. Association of human papillomavirus status at head and neck carcinoma subsites with overall survival. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144(6):519.

Chen L, Dong P, Yu Z. Detection of human papillomavirus infection in laryngeal and hypopharyngeal carcinoma using droplet digital PCR and its correlation with prognosis. Postgrad Med. 2021;133(6):619–25.

Hughes RT, Beuerlein WJ, O’Neill SS, et al. Human papillomavirus-associated squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx or hypopharynx: clinical outcomes and implications for laryngeal preservation. Oral Oncol. 2019;98:20–7.

Dahm V, Haitel A, Kaider A, Stanisz I, Beer A, Lill C. Cancer stage and pack-years, but not p16 or HPV, are relevant for survival in hypopharyngeal and laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275(7):1837–43.

Ernoux-Neufcoeur P, Arafa M, Decaestecker C, et al. Combined analysis of HPV DNA, p16, p21 and p53 to predict prognosis in patients with stage IV hypopharyngeal carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137(1):173–81.

Zhu G, Amin N, Herberg ME, et al. Association of tumor site with the prognosis and immunogenomic landscape of human papillomavirus-related head and neck and cervical cancers. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;148(1):70–9.

Fakhry C, Westra WH, Wang SJ, et al. The prognostic role of sex, race, and human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal and nonoropharyngeal head and neck squamous cell cancer: role of sex, race, and HPV in HNSCC prognosis. Cancer. 2017;123(9):1566–75.

Kobayashi K, Yoshimoto S, Ando M, et al. Full-coverage TP53 deep sequencing of recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma facilitates prognostic assessment after recurrence. Oral Oncol. 2021;113:105091.

Donehower LA, Soussi T, Korkut A, et al. Integrated analysis of TP53 gene and pathway alterations in the cancer genome atlas. Cell Rep. 2019;28(5):1370-1384.e5.

Freed-Pastor WA, Prives C. Mutant p53: one name, many proteins. Genes Dev. 2012;26(12):1268–86.

Poeta ML, Forastiere A, Ridge JA, Saunders J, Koch WM. TP53 mutations and survival in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Eng J Med. 2007;357(25):2552–61.

Singh V, Husain N, Akhtar N, Khan MY, Sonkar AA, Kumar V. p16 and p53 in HPV-positive versus HPV-negative oral squamous cell carcinoma: do pathways differ? J Oral Pathol Med. 2017;46(9):744–51.

Hong A, Zhang X, Jones D, et al. Relationships between p53 mutation, HPV status and outcome in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2016;118(2):342–9.

Bian ML, Cheng JY, Ma L, et al. Evaluation of the detection of 14 high-risk human papillomaviruses with HPV 16 and HPV 18 genotyping for cervical cancer screening. Exp Ther Med. 2013;6(5):1332–6.

Yang H, Li LJ, Xie LX, et al. Clinical validation of a novel real-time human papillomavirus assay for simultaneous detection of 14 high-risk HPV type and genotyping HPV type 16 and 18 in China. Arch Virol. 2016;161(2):449–54.

Li T, Fu J, Zeng Z, et al. TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(W1):W509–14.

Westra WH, Taube JM, Poeta ML, Begum S, Sidransky D, Koch WM. Inverse relationship between human papillomavirus-16 infection and disruptive p53 gene mutations in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(2):366–9.

Ndiaye C, Mena M, Alemany L, et al. HPV DNA, E6/E7 mRNA, and p16INK4a detection in head and neck cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):1319–31.

Biesaga B, Mucha-Małecka A, Janecka-Widła A, et al. Differences in the prognosis of HPV16-positive patients with squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck according to viral load and expression of P16. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2018;144(1):63–73.

Lechner M, Chakravarthy AR, Walter V, et al. Frequent HPV-independent p16/INK4A overexpression in head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2018;83:32–7.

Chien CY, Huang CC, Cheng JT, Chen CM, Hwang CF, Su CY. The clinicopathological significance of p53 and p21 expression in squamous cell carcinoma of hypopharyngeal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2003;201(2):217–23.

Maruyama H, Yasui T, Ishikawa-Fujiwara T, et al. Human papillomavirus and p53 mutations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma among Japanese population. Cancer Sci. 2014;105(4):409–17.

Boscolo-Rizzo P, Schroeder L, Sacchetto V, et al. Absence of disruptive TP53 mutations in high-risk human papillomavirus-driven neck squamous cell carcinoma of unknown primary. Head Neck. 2019;41(11):3833–41.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from Shanghai Sailing Program (23YF1404700).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and analysis were performed by Qiang Huang and Feiran Li. Data collection was performed by Mengyou Ji. IHC staining and assessing were performed by Lan Lin and Chunyan Hu. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Qiang Huang and Feiran Li and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The current study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Eye & ENT Hospital of Fudan University (No. 2018036) and performed in strict accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants in this study signed informed consent documentation before sample collection. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Q., Li, F., Ji, M. et al. Evaluating the prognostic significance of p53 and TP53 mutations in HPV-negative hypopharyngeal carcinoma patients: a 5-year follow-up retrospective study. BMC Cancer 23, 324 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-10775-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-10775-9