Abstract

Background

Colorectal cancer is the third most diagnosed cancer globally and the second leading cause of cancer death. We examined colon and rectal cancer treatment patterns in Australia.

Methods

From cancer registry records, we identified 1,236 and 542 people with incident colon and rectal cancer, respectively, diagnosed during 2006-2013 in the 45 and Up Study cohort (267,357 participants). Cancer treatment and deaths were determined via linkage to routinely collected data, including hospital and medical services records. For colon cancer, we examined treatment categories of “surgery only”, “surgery plus chemotherapy”, “other treatment” (i.e. other combinations of surgery/chemotherapy/radiotherapy), “no record of cancer-related treatment, died”; and, for rectal cancer, “surgery only”, “surgery plus chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy”, “other treatment”, and “no record of cancer-related treatment, died”. We analysed survival, time to first treatment, and characteristics associated with treatment receipt using competing risks regression.

Results

86.4% and 86.5% of people with colon and rectal cancer, respectively, had a record of receiving any treatment ≤2 years post-diagnosis. Of those treated, 93.2% and 90.8% started treatment ≤2 months post-diagnosis, respectively. Characteristics significantly associated with treatment receipt were similar for colon and rectal cancer, with strongest associations for spread of disease and age at diagnosis (p<0.003). For colon cancer, the rate of “no record of cancer-related treatment, died” was higher for people with distant spread of disease (versus localised, subdistribution hazard ratio (SHR)=13.6, 95% confidence interval (CI):5.5-33.9), age ≥75 years (versus age 45-74, SHR=3.6, 95%CI:1.8-7.1), and visiting an emergency department ≤1 month pre-diagnosis (SHR=2.9, 95%CI:1.6-5.2). For rectal cancer, the rate of “surgery plus chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy” was higher for people with regional spread of disease (versus localised, SHR=5.2, 95%CI:3.6-7.7) and lower for people with poorer physical functioning (SHR=0.5, 95%CI:0.3-0.8) or no private health insurance (SHR=0.7, 95%CI:0.5-0.9).

Conclusion

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, most people with colon or rectal cancer received treatment ≤2 months post-diagnosis, however, treatment patterns varied by spread of disease and age. This work can be used to inform future healthcare requirements, to estimate the impact of cancer control interventions to improve prevention and early diagnosis, and serve as a benchmark to assess treatment delays/disruptions during the pandemic. Future work should examine associations with clinical factors (e.g. performance status at diagnosis) and interdependencies between characteristics such as age, comorbidities, and emergency department visits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer globally, and the second leading cause of cancer death [1, 2]. CRC incidence and mortality rates have been decreasing in high income countries, which has been largely attributed to the early detection of pre-cancerous lesions (polyps) or early-stage cancer through screening and advancements in treatment [3,4,5]. However, the numbers of cases and deaths remain high due to an ageing population, leading to substantial healthcare requirements and costs. Moreover, in high-income countries, CRC incidence rates are increasing in adults aged <50 years [6].

In Australia, a high-income country with universal healthcare supplemented by private health insurance, cancer accounts for the third highest disease expenditure to the health system [7], and CRC was the costliest cancer type to treat in 2013 [8]. CRC treatment costs are particularly high in the first year after diagnosis compared to other cancer types [8], and healthcare costs and utilisation are higher for those with advanced spread of disease [9]. Understanding CRC treatment patterns and their association with specific characteristics of people with colon and rectal cancer (e.g. age, cancer stage at diagnosis) is important for estimating future healthcare requirements and the current and future impact of cancer control interventions.

To date, Australian data on colon and rectal cancer treatment patterns are limited and focus on specific treatments [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Moreover, most existing studies have examined colon and rectal cancers combined, while the management and treatment of these cancer types differ [17,18,19]. There are also limited Australian data on the time from a CRC diagnosis to first cancer treatment. A recent systematic review found that system-level delays in cancer treatment are associated with increased cancer mortality [20]. In view of treatment disruptions that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, benchmarks of pre-pandemic time to treatment are important to estimate the impact of treatment delays.

In this study, we examined cancer treatment patterns for people with incident colon cancer and separately, incident rectal cancer in the 45 and Up Study, a large cohort of Australian residents. We describe treatment patterns for specific treatment combinations by spread of disease at diagnosis, estimate time from diagnosis to first treatment received, and identify associations between characteristics of people with colon and rectal cancer and treatment receipt.

Methods

Study cohort

We utilised the Sax Institute’s 45 and Up Study cohort of 267,357 participants from New South Wales (NSW), Australia, recruited from 2005 to 2009 [21, 22]. Briefly, adults aged ≥45 years were randomly sampled from the Services Australia Medicare enrolment database (MEDB) if they had received medical care within the previous two years [22]. MEDB has near-complete coverage of the population. People living in remote and rural areas and those aged ≥80 years were oversampled. Overall, the response rate was ~19% and the cohort represents ~11% of the NSW population aged ≥45 years. Participants completed a questionnaire containing health, lifestyle and sociodemographic information at baseline [23], and consented to be followed-up through questionnaires and linkage to routinely collected administrative health databases.

Baseline questionnaire information was linked to health databases to identify incident cancers, deaths, and cancer treatment received (i.e., surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy), as well as clinical, sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics of people with cancer. We linked to available data at the time of linkage, including: (a) NSW Cancer Registry (NSWCR; Jan-1994 to Dec-2013) to ascertain colon and rectal cancers diagnosed after baseline according to the International Classification of Diseases 10 Australian Modification (ICD-10 AM) [24], some characteristics of people with cancer (see below), and cause of death after diagnosis; (b) Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages (RBDM; Jan-2006 to Jun-2017) to identify deaths after diagnosis; (c) Emergency Department Data Collection (EDDC; Jan-2005 to Dec-2013) to identify emergency department visits pre-diagnosis; (d) Admitted Patient Data Collection (APDC; Jul-2001 to Dec-2015) to identify comorbidities pre-diagnosis and cancer treatment received in hospital post-diagnosis; (e) Medicare Benefits Schedule (Jan-2006 to Dec-2016) to identify other cancer treatment received post-diagnosis and (f) Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (Jan-2006 to Dec-2016) to identify government-subsidised chemotherapy received post-diagnosis. Databases (a)-(d) were probabilistically linked by the Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL) [25]. Databases (e)-(f) were supplied by Services Australia and deterministically linked by the Sax Institute using a unique identifier provided by Services Australia.

Ascertainment of people with cancer

We excluded cohort participants who withdrew, were part of the pilot study, <45 years old, a Department of Veterans' Affairs client (as their available treatment data are incomplete), had a self-reported cancer diagnosed prior to 1994, or with linkage errors. We identified incident colon cancers (ICD-10 AM code C18) and rectal cancers (C19-20) using NSWCR records, and excluded those with multiple cancer diagnoses, a cancer diagnosis before or at baseline, exact month of diagnosis not recorded, or cancer diagnosis based on death certificate only.

Characteristics of people with cancer

A total of 16 characteristics were examined. We obtained age, spread of disease, place of residence (using the Accessibility and Remoteness Index of Australia plus [ARIA+] [26]) and area-level socioeconomic status (SES; using the Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage (IRSD) [27]) from NSWCR, all at time of cancer diagnosis. From the self-reported baseline questionnaire, we obtained sex, smoking status, body mass index (kg/m2), highest educational qualification, private health insurance status, marital status, language other than English spoken at home, Medical Outcomes Study Physical Functioning 10 (MOSPF-10) score [28, 29], faecal occult blood testing (FOBT) history (ever/never), and sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy history (ever/never). Charlson’s Comorbidity Index was derived from APDC records using the ICD-10-AM codes specified by [30] and conditions scored as in [31], capturing conditions in the 5 years pre-diagnosis (Additional file 1). Emergency department visits from EDDC records were captured for the 31 days pre-diagnosis.

Cancer treatment utilisation

We focused on surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatment in the 0-2 years after diagnosis (codes are listed in Additional file 2). We considered all treatment combinations, or no record of these cancer-related treatments ≤2 years post-diagnosis. Treatment combinations were grouped into five categories for each cancer type to ensure a sufficient sample size (Additional file 3). For colon cancer, categories included “surgery only” and “surgery plus chemotherapy”; and for rectal cancer, “surgery only” and “surgery plus chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy”.

Treatment combinations containing smaller sample sizes were grouped into the “other treatment” category: for colon and rectal cancer, this included i) chemotherapy only, ii) radiotherapy only, iii) chemotherapy plus radiotherapy; for colon cancer, it additionally included iv) surgery plus radiotherapy, v) surgery plus chemotherapy plus radiotherapy. For both cancers, we also considered categories of “no record of cancer-related treatment, died”, and “no record of cancer-related treatment, alive” based on the same period (2 years post-diagnosis), hereafter referred to as “no treatment, died” and “no treatment, alive” categories, respectively.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Stata version 17.0 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX).

We estimated survival using the cumulative incidence function, applied with the SAS macro %CIF. The survival function is defined as 1 minus the cumulative incidence function (CIF). 1-,2-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival after a colon or rectal cancer diagnosis, by spread of disease, were estimated using RBDM records. Individuals alive at the end of the follow-up (for this analysis, 30 June 2017) were censored. 1- and 2-year cancer-specific survival after diagnosis, by spread of disease, were estimated using NSWCR records. Death from other causes (i.e., codes other than C18 for colon cancer and C19-20 for rectal cancer) were competing events, censoring those alive at the end of follow-up (for this analysis, 31 December 2013).

We examined frequencies of treatment categories based on treatment received in the 0-2 years post-diagnosis (with sensitivity analyses based on the 0-1 and 0-5 years post-diagnosis, Additional file 3).

We carried out two time-to-treatment analyses based on treatment 0-2 years post-diagnosis. In the first analysis, we considered all cases with colon cancer or, separately, rectal cancer, and measured time from the date of diagnosis to date of first treatment, date of death, or end of follow-up (2 years post-diagnosis) using Fine and Gray’s competing risks cumulative incidence function (CIF) [32, 33] with the SAS macro %CIF. We used the CIF rather than the Kaplan-Meier method as the presence of competing risks may violate the assumption of non-informative censoring of the Kaplan-Meier method. The competing events were all treatment categories other than the treatment category of interest, in addition to the category “no treatment, died”. Those assigned to “no treatment, alive” were censored. In the second analysis, we considered only those cases who had a record of treatment receipt, and used the empirical cumulative distribution function (ECDF) to estimate time to first treatment receipt for these cases, by treatment category (with categories based on all treatment 0-2 years post-diagnosis). As an additional analysis, we used the ECDF to examine time to first treatment for those who received treatment, by spread of disease.

For people with “no record of cancer-related treatment, alive” at 2 years post-diagnosis, we considered records of procedures that could indicate potential CRC surveillance following definitive treatment not captured in the linked data (e.g. all tumour tissue excised through the initial biopsy). In particular, we calculated the proportion of these people who had records of computed tomography (CT) scan and/or colonoscopy ≤2 years post-diagnosis (see Additional file 2 for procedure codes) [34].

For the association analyses between treatment receipt and clinical/sociodemographic/lifestyle characteristics, we used Fine and Gray’s competing risks subdistribution hazard model and the SAS procedure PHREG with ‘eventcode’ and ‘rl’ options to obtain subdistribution hazard ratios (SHRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For each treatment category, other treatment categories and death were competing events. For the outcome “no treatment, died”, the treatment categories were the competing events. For all models, those with “no treatment, alive” at 2-years post-diagnosis were censored. Estimates were fully adjusted for all characteristics in the model. For characteristics with missing data for ≥5% of people with cancer, missing values were treated as a separate “unspecified” category. For characteristics with missing data for <5% of people with colon or rectal cancer, individuals with missing values were excluded from the association analyses. The number of people with colon and rectal cancer, by each characteristic and treatment category, is shown in Additional file 4. The proportional subdistribution hazard assumption was assessed using the STATA package STCRREG with ‘tvc’ option. Significance was defined using Bonferroni adjustment for 16 tests (i.e., p<0.003, accounting for 16 characteristics).

Previous studies indicate that the subdistribution hazard model is the recommended method for estimating incidence in the presence of competing risks, whereas Cox’s cause-specific hazard model is recommended when the focus is on addressing aetiological questions [32, 35]. To allow for a comprehensive understanding of all event dynamics, we additionally 1) estimated hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs using separate Cox’s cause-specific hazards models for each outcome [35], and 2) used the joint Cox model [36, 37] to examine the association between each characteristic and all outcomes in the same model. For both analyses, we used the SAS procedure PHREG. Detailed descriptions of all three models are shown in Additional file 5.

Results

We included 1,236 and 542 participants in the 45 and Up Study with a new colon and rectal cancer diagnosis in 2006-2013, respectively (Additional file 6).

People with incident colon cancer had a median age of 72 years at diagnosis (interquartile range (IQR) 65-80). 33.4% had localised spread of disease, 40.6% had regional and 20.4% had distant disease at diagnosis, similar to all people diagnosed with colon cancer in NSW and Australia during 2010-2017 (Additional file 7). 1-, 2- and 5-year overall survival was 84.2%, 76.4% and 63.7%, respectively (Additional file 8). We found substantial variation by spread of disease, e.g. 5-year overall survival was 85.3%, 68.6% and 15.9% for people with localised disease, regional and distant spread of disease, respectively. 1- and 2-year cancer-specific survival was 86.4% and 79.8%, respectively (Additional file 9).

People with rectal cancer had a median age of 68 years at diagnosis (IQR 61-77). 33.2% had localised disease and 16.4% had distant disease, similar to all people diagnosed with rectal cancer in NSW and Australia (Additional file 7), with a slightly larger proportion of people in the 45 and Up Study with regional disease (42.1% versus 32.5% for all people with incident rectal cancer in NSW). 1-, 2- and 5-year overall survival was 87.1%, 81.2% and 66.7%, respectively (Additional file 8), also with strong differences by spread of disease (e.g. 5-year overall survival was 84.0%, 71.0% and 15.7% for people with localised disease, regional and distant spread of disease, respectively). 1- and 2-year cancer-specific survival was 90.4% and 84.3%, respectively (Additional file 9).

Receipt of cancer treatment

Colon cancer

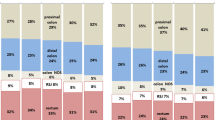

In the 0-2 years after diagnosis, 50.2% of all people with colon cancer had “surgery only”, 27.7% “surgery plus chemotherapy”, 8.6% “other treatment”, and 6.3% “no treatment, died” (Fig. 1A and Additional file 3). 7.3% were assigned to “no treatment, alive”; of these people, 73.3% had a CT scan and/or colonoscopy in the 2 years post-diagnosis, indicating potential surveillance for CRC, possibly following definitive treatment not captured by the linked data. Treatment receipt varied greatly by spread of disease. A higher proportion of people with localised disease had “surgery only” (78.9%), compared to 44.2% and 15.1% of people with regional and distant spread of disease, respectively. A similar proportion of people with regional and distant disease had “surgery plus chemotherapy” (42.6% and 38.1%, respectively). Treatment receipt for people with distant disease was more heterogenous (15.1% had “surgery only”, 23.8% “other treatment” and n~58 (23.0%) “no treatment, died”).

Cancer treatment received by 45 and Up Study participants with incident colon cancer (left; n=1,236) or rectal cancer (right; n=542) after baseline. A Treatment received in the 0-2 years after the cancer diagnosis, by spread of disease at diagnosis. Exact percentages and estimates based on the 0-1 and 0-5 years after diagnosis are provided in Additional file 3. B Time from diagnosis to first cancer treatment, by treatment category based on all treatment in the 0-2 years after diagnosis. The figure includes only people who received treatment within 2 years after their cancer diagnosis (n=1068 for colon cancer, n=469 for rectal cancer). The cumulative percentage was obtained using the empirical cumulative distribution function

86.4% of all people with colon cancer received treatment (Additional file 10). Of those treated, 75.8%, 93.3% and 97.8% received their first treatment within 1, 2 and 3 months after diagnosis, respectively (Fig. 1B). Time to treatment receipt differed by treatment category. For example, 97.7% of people who had “surgery plus chemotherapy” received their first treatment ≤2 months post-diagnosis, compared to 75.5% of people with final treatment in the “other treatment” category. Time to treatment receipt was similar by spread of disease (Additional file 11).

Rectal cancer

In the 0-2 years after diagnosis, 31.7% of all people with rectal cancer had “surgery only”, 44.5% “surgery plus chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy”, 10.3% “other treatment”, and 5.0% “no treatment, died” (Fig. 1A and Additional file 3). 8.5% of people with rectal cancer were assigned to “no treatment, alive”; of these, 76.1% had a CT scan and/or colonoscopy in the 2 years post-diagnosis, indicating potential surveillance for CRC (as for colon cancer above). Similar to colon cancer, the treatment received varied by spread of disease. A higher proportion of people with localised disease had “surgery only” compared to distant disease (56.1% versus 11.2%, respectively), more people with regional or distant spread disease had “surgery plus chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy” (67.5% and 41.6%, respectively), and a larger proportion of those with distant disease were assigned to “no treatment, died” (n~16 (18.0)% versus n<5 (≤3%) of people with localised disease and regional spread).

86.5% of all people with rectal cancer received treatment (Additional file 10). Of those treated, 61.4%, 90.8% and 97.0% received their first treatment within 1, 2 and 3 months after diagnosis, respectively (Fig. 1B). Time to treatment for rectal cancer also differed by treatment category. For example, 96.3% of people who had “surgery plus chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy” received their first treatment within 2 months after diagnosis, compared to 69.6% of people with final treatment in the “other treatment” category. Time to treatment receipt was similar by spread of disease (Additional file 11).

Characteristics associated with treatment receipt

The association analyses included 1,149 and 499 people with colon and rectal cancer, respectively (see Methods).

Colon cancer

Characteristics significantly associated with colon cancer treatment receipt include age at diagnosis, spread of disease and emergency presentation (all p≤0.003, Fig. 2 and Additional file 12; here and below, after adjusting for all other characteristics). Compared to people with colon cancer aged 45-75 years, those aged ≥75 years had a higher rate of “no treatment, died” (SHR=3.6, 95%CI:1.8-7.1) or “surgery only” (SHR=1.5, 95%CI:1.3-1.8), and a lower rate of “surgery plus chemotherapy” (SHR=0.4, 95%CI:0.3-0.6). People with regional or distant spread of disease had a higher rate of “surgery plus chemotherapy” (SHR=11.6, 95%CI:7.4-18.3 and SHR=9.0, 95%CI: 5.5-14.7, respectively) or “other treatment” (SHR=3.5, 95%CI:1.6-7.6 and SHR=15.1, 95%CI: 6.8-33.2, respectively), and a lower rate of “surgery only” (SHR=0.4, 95%CI:0.3-0.5 and SHR=0.1, 95%CI:0.1-0.2, respectively), than people with localised disease. People with distant spread of disease had a higher rate of “no treatment, died” (SHR=13.6, 95%CI:5.5-33.9) compared to those with localised disease. An emergency department visit ≤1 month pre-diagnosis was significantly associated with “no treatment, died” (SHR=2.9, 95%CI:1.6-5.2).

Association between characteristics of colon cancer cases and cancer treatment received in the 0-2 years after the cancer diagnosis, separately for each treatment category. Subdistribution hazard ratios were adjusted for all characteristics shown in the figure. Bars show 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). Numbers of cases in each category are shown in Additional file 4; subdistribution hazard ratio estimates, 95%CIs and p-values are detailed in Additional file 12

Characteristics with only nominally significant associations with colon cancer treatment receipt (0.003<p≤0.05) include sex, Charlson’s comorbidity index, level of physical functioning, place of residence and private health insurance. Females had a lower rate of “no treatment, died” (SHR=0.6, 95%CI:0.3-1.0). People with a Charlson’s comorbidity index score 1 had a lower rate of “surgery plus chemotherapy" (SHR=0.5, 95%CI: 0.3-1.0) than those with score 0. People with unspecified physical functioning (i.e. missing responses to some questionnaire items) had a higher rate of “surgery plus chemotherapy” (SHR=1.7, 95%CI:1.2-2.4) than those with high physical functioning. People with colon cancer living outside major cities had a higher rate of “surgery only” (SHR=1.2, 95%CI:1.0-1.5) and people with no private health insurance had a lower rate of “surgery plus chemotherapy” (SHR=0.7, 95%CI:0.6-0.9).

Rectal cancer

Characteristics significantly associated with rectal cancer treatment receipt were age at diagnosis, spread of disease and level of physical functioning at baseline (all p≤0.003, Fig. 3 and Additional file 13). People with rectal cancer aged ≥75 years had a higher rate of “no treatment, died” (SHR=6.6, 95%CI:1.9-23.0), and lower rate of “surgery plus chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy” (SHR=0.6, 95%CI:0.4-0.8) than people aged 45-74 years. People with regional or distant spread of disease had a higher rate of “surgery plus chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy” (SHR=5.2, 95%CI:3.6-7.7 and SHR=2.7, 95%CI: 1.6-4.4, respectively) and lower rate of “surgery only” (SHR=0.3, 95%CI:0.2-0.4 and SHR=0.1, 95%CI:0.1-0.3, respectively) than people with localised disease. People with distant spread of disease had a higher rate of “no treatment, died” (SHR=19.1, 95%CI:2.1-177.4) or “other treatment” (SHR=8.4, 95%CI:3.1-22.4) than people with localised disease. People with lower physical functioning at baseline had a lower rate of “surgery plus chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy” than people with higher physical functioning (e.g., 0-59 low functioning versus 90-100 high functioning SHR=0.5, 95%CI:0.3-0.8).

Association between characteristics of rectal cancer cases and cancer treatment received in the 0-2 years after the cancer diagnosis, separately for each treatment category. Subdistribution hazard ratios were adjusted for all characteristics shown in the figure. Bars shows 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). Numbers of cases in each category are shown in Additional file 4; subdistribution hazard ratio estimates, 95%CIs and p-values are detailed in Additional file 13

Characteristics with only nominally significant associations with rectal cancer treatment receipt include sex, emergency presentation, private health insurance and language other than English spoken at home (0.003<p≤0.05). Females had a higher rate of “surgery only” (SHR=1.4, 95%CI:1.0-2.0). An emergency department visit ≤1 month pre-diagnosis was associated with “no treatment, died” (SHR=4.0, 95%CI:1.3-12.5), “other treatment” (SHR=2.7, 95%CI:1.3-5.6), and “surgery plus chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy” (SHR=0.5, 95%CI:0.2-0.9). People with rectal cancer and no private health insurance had a higher rate of “other treatment” (SHR=2.1, 95%CI:1.1-3.9) and lower rate of “surgery plus chemotherapy and or radiotherapy” (SHR=0.7, 95%CI:0.5-0.9). People who spoke a language other than English at home had a lower rate of “surgery plus chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy” (SHR=0.5, 95%CI:0.3-0.9).

The additional analyses using cause-specific and joint Cox hazard model indicate there was high agreement across all models on the characteristics most strongly associated with treatment receipt (p<0.003; Additional files 12 and 13). All three models also consistently produced effect estimates indicating the same direction of effect.

Discussion

This study provides detailed insights into the treatment patterns of incident colon and rectal cancer cases in Australia. Our results highlight that 86.4% of colon and 86.5% of rectal cancer cases had a record of receiving treatment within 2 years post-diagnosis, and of those treated, 93.2% and 90.8% received their first treatment within 2 months after diagnosis, respectively. Characteristics significantly associated with treatment receipt were generally similar for both cancers; the strongest associations were with spread of disease and age at diagnosis.

Among 45 and Up Study participants with colon and rectal cancer, the distribution for spread of disease at diagnosis was similar to that reported for all people with colon and rectal cancer in NSW in 2013-2017 [38]. Moreover, the 5-year relative survival for Australians aged ≥50 years who were diagnosed with colorectal cancer in 2011 was 69.6% [39], broadly consistent with the 5-year overall survival estimates from this study (63.6% for colon cancer and 66.7% for rectal cancer, noting the difference in survival measures).

Time from diagnosis to treatment

Recommendations for timelines from diagnosis to cancer treatment exist in multiple countries [17, 20]. In Australia, the optimal care pathway guidelines [17, 18, 40] suggest an optimal timeframe of up to 7-9 weeks from a colon or rectal cancer diagnosis to first treatment, broadly similar to the National Health Service UK guidelines [41]. In our study, of the colon and rectal cancer cases who received treatment, 93.2% and 90.8% had their first treatment ≤2 months post-diagnosis, respectively, indicating the majority of cases received treatment within the optimal timeframe. However, this varied by treatment category. 97.7% and 96.3% of people with colon and rectal cancer with a final category of “surgery plus chemotherapy” or “surgery plus chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy”, respectively, received treatment ≤2 months after diagnosis. By contrast, only 75.5% and 69.6% of people with colon and rectal cancer with final categories of “other treatment” received treatment in this same timeframe (though this might be partially due to “other treatment” also including mainly palliative treatments, in which case earlier care may not necessarily represent optimal care). In general, timeliness of treatment is an important factor of cancer care, and important to benchmark to assess the long-term consequences of cancer care delays and disruptions. This necessity has been highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the emerging impact on cancer outcomes [42, 43].

Characteristics associated with different treatment categories

Spread of disease was the strongest predictor of treatment received ≤2 years after diagnosis. People with localised disease had a higher rate of “surgery only”. People with distant spread of disease had a higher rate of “no treatment, died”. People with colon cancer and regional or distant spread of disease had a higher rate of “surgery plus chemotherapy” or “other treatment”, and people with rectal cancer and with regional or distant spread of disease had a higher rate of “surgery plus chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy”. These results are broadly consistent with the previous and current guidelines for the treatment of CRC [17,18,19, 44]. For example, for stage I disease, surgery is the main treatment, whereas there are several different treatment pathways for stage IV disease. This emphasises the complexity of treating advanced-stage disease, and the importance of early diagnosis. Detection at early stages can improve survival and lessen the demand for more complex treatment and reduce associated treatment cost [8]; in Australia, screening provided by the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program has been shown to improve CRC outcomes [45, 46].

People with colon and rectal cancer and older at diagnosis had a higher rate of no treatment record and death, an association well documented in Australia [9, 14] and worldwide [3, 5]. Colon and rectal cancer treatment decisions for older and often frailer patients are complex. Older patients are underrepresented in clinical trials, creating an evidence gap which makes it even more challenging for physicians to make optimal treatment decisions for this group [47, 48]. With ageing populations in high-income countries, it is important to address this evidence gap.

People with colon and rectal cancer and private health insurance and/or better overall health (e.g. higher physical functioning at baseline and fewer comorbidities) had a higher rate of the treatment categories “surgery plus chemotherapy” or “surgery plus chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy”, respectively. Previous research found 45 and Up Study participants with private health insurance at baseline were more likely to have higher education, be health conscious, and have higher income at baseline [49]. This may suggest different health-seeking behaviours for individuals with private health insurance. People with rectal cancer who spoke a language other than English at home were also less likely to receive “surgery plus chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy”. The combination of these factors suggest specific groups may have different access to cancer treatment services, warranting further investigation.

We also found 22.8% and 10.4% of people with colon and rectal cancer, respectively, visited an emergency department in the month prior to diagnosis; this was associated with the “no treatment, died” category. However, we cannot determine if the emergency department visit was related to the cancer diagnosis (see Additional file 14 for further discussion). Moreover, there may be interdependencies between emergency department visits and other characteristics, especially the presence of comorbidities (which in turn is also related to age). In-depth investigation of such complex relationships and their impact on treatment receipt would require large sample sizes. This was beyond the scope of the current study and could be the subject of future work.

Implications

The estimates reported here will add to the understanding of colon and rectal cancer treatment patterns in Australia and inform future research on optimising CRC outcomes. The study findings can be used to inform the inclusion of treatment pathways in predictive models of CRC, previously used to evaluate the health outcomes and cost-effectiveness of screening and other interventions targeted at reducing the burden of colon and rectal cancer [46, 50,51,52,53]. For example, Policy1-Bowel is a comprehensive, calibrated and validated microsimulation modelling platform for colon and rectal cancer in Australia that incorporates multiple aspects of cancer control and has already informed several national policy decisions [46, 50,51,52].

Limitations and strengths

Our study has some limitations. We did not have detailed TNM staging of disease and were unable to examine alignment of treatment patterns with the clinical practice guidelines, or to which extent patients’ preferences or specific clinical considerations influenced treatment decisions. Data on Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status at diagnosis was not available. Characteristics obtained at baseline may have changed before cancer diagnosis. There is also the potential for residual confounding in the analyses examining characteristics associated with treatment receipt. The 45 and Up Study cohort does not include participants <45 years old, for whom treatment patterns may be different [54]. Cohort participants are also generally more socioeconomically advantaged, healthier and more health conscious, therefore, estimates from this study may not be entirely representative of the Australian population. The examined treatment categories were defined based on all treatment records in the 0-2 years post-diagnosis, which may have included treatment for stage progression and/or recurrence. However, sensitivity analyses based on the treatment in the 0-6 months or 0-1 years post-diagnosis showed very similar frequencies of all treatment categories (see Additional file 3). Some of the treatment categories had small sample sizes, including “no treatment, died” category; thus some hazard ratio estimates have wide confidence intervals and may not be robustly estimated. However, our study also has notable strengths, including extensive linkage to routinely collected health data, which enabled detailed insights into treatment patterns and the associations between different characteristics and treatment receipt. Our study includes a larger sample than previous Australian studies, allowing us to separately examine colon and rectal cancer. Finally, we considered different treatment combinations rather than single types of treatment, which allowed for separate examination of more complex treatment approaches, e.g. distinguishing surgery only and surgery plus chemotherapy.

Conclusion

The characterisation of colon and rectal cancer treatment patterns and their considerable variation by spread of disease and age can help estimate future healthcare requirements with rising colon and rectal cancer burden, and help model the health and economic impacts of cancer control interventions to improve prevention and early diagnosis. The assessment of time to treatment prior to the COVID-19 pandemic can also be used as a benchmark against which to assess the extent of treatment delays and disruptions during the pandemic.

Availability of data and materials

The 45 and Up Study data that support the findings of this study are available from the Sax Institute (see https://www.saxinstitute.org.au/our-work/45-up-study/for-researchers/ for details) but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Therefore, the authors cannot on-provide the data to other researchers. However, researchers are able to access these data from the relevant data custodians for approved research projects, and enquiries for data access can be made to the Sax Institute.

Abbreviations

- APDC:

-

Admitted Patient Data Collection

- ARIA:

-

Accessibility and Remoteness Index of Australia

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- CIF:

-

Cumulative Incidence Function

- CRC:

-

Colorectal Cancer

- CT:

-

Computed Tomography

- ECDF:

-

Empirical Cumulative Distribution Function

- EDDC:

-

Emergency Department Data Collection

- FOBT:

-

Faecal Occult Blood Test

- MOSPF-10:

-

Medical Outcomes Study Physical Functioning 10

- NSW:

-

New South Wales

- NSWCR:

-

New South Wales Cancer Registry

- RBDM:

-

Registry of Births, Death and Marriages

- SEIFA:

-

Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas

- SES:

-

Socio-Economic Status

- SHR:

-

Subdistribution Hazard Ratio

- TNM:

-

Tumour, Nodes, Metastases

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer data in Australia. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-data-in-australia/contents/summary. Accessed 15 Apr 2021.

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

Araghi M, Arnold M, Rutherford MJ, Guren MG, Cabasag CJ, Bardot A, et al. Colon and rectal cancer survival in seven high-income countries 2010–2014: variation by age and stage at diagnosis (the ICBP SURVMARK-2 project). Gut. 2021;70(1):114–26.

Feletto E, Yu XQ, Lew JB, St John DJB, Jenkins MA, Macrae FA, et al. Trends in Colon and Rectal Cancer Incidence in Australia from 1982 to 2014: Analysis of Data on Over 375,000 Cases. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2019;28(1):83–90.

Chawla N, Butler EN, Lund J, Warren JL, Harlan LC, Yabroff KR. Patterns of colorectal cancer care in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2013;2013(46):36–61.

Siegel RL, Torre LA, Soerjomataram I, Hayes RB, Bray F, Weber TK, et al. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence in young adults. Gut. 2019;68(12):2179–85.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health system expenditure on cancer and other neoplasms in Australia. 2015-2016. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/health-system-expenditure-cancer-other-neoplasms/summary. Accessed 15 Apr 2021.

Goldsbury DE, Yap S, Weber MF, Veerman L, Rankin N, Banks E, et al. Health services costs for cancer care in Australia: Estimates from the 45 and Up Study. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0201552.

Goldsbury DE, Feletto E, Weber MF, Haywood P, Pearce A, Lew JB, et al. Health system costs and days in hospital for colorectal cancer patients in New South Wales, Australia. PLoS One. 2021;16(11):e0260088.

Semira C, Wong HL, Field K, Lee M, Lee B, Nott L, et al. Chemotherapy and biologic use in the routine management of metastatic colorectal cancer in Australia: is clinical practice following the evidence? Intern Med J. 2019;49(4):446–54.

Roder D, Karapetis CS, Olver I, Keefe D, Padbury R, Moore J, et al. Time from diagnosis to treatment of colorectal cancer in a South Australian clinical registry cohort: how it varies and relates to survival. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e031421.

Young JM, Durcinoska I, DeLoyde K, Solomon MJ. Patterns of follow up and survivorship care for people with colorectal cancer in new South Wales, Australia: a population-based survey. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):339.

Adelson P, Fusco K, Karapetis C, Wattchow D, Joshi R, Price T, et al. Use of guideline-recommended adjuvant therapies and survival outcomes for people with colorectal cancer at tertiary referral hospitals in South Australia. J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24(1):135–44.

Parakh S, Wong HL, Rai R, Ali S, Field K, Shapiro J, et al. Patterns of care and outcomes for elderly patients with metastatic colorectal cancer in Australia. J Geriatr Oncol. 2015;6(5):387–94.

Jorgensen ML, Young JM, Dobbins TA, Solomon MJ. Does patient age still affect receipt of adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer in New South Wales, Australia? J Geriatr Oncol. 2014;5(3):323–30.

Beckmann KR, Bennett A, Young GP, Roder DM. Treatment patterns among colorectal cancer patients in South Australia: a demonstration of the utility of population-based data linkage. J Eval Clin Pract. 2014;20(4):467–77.

Cancer Council Victoria. Optimal care pathways for people with colorectal cancer second edition. 2021. https://www.cancer.org.au/assets/pdf/colorectal-cancer-optimal-cancer-care-pathway. Accessed 1 Apr 2021.

Cancer Council Australia. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, early detection and management of colorectal cancer. 2017. https://wiki.cancer.org.au/australia/Guidelines:Colorectal_cancer. Accessed 15 Apr 2021.

Australian Cancer Network and the Cancer Council Australia. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the prevention, early detection and management of colorectal cancer. 2005. p. 369.

Hanna TP, King WD, Thibodeau S, Jalink M, Paulin GA, Harvey-Jones E, et al. Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;371:m4087.

45 and Up Study Collaborators, Banks E, Redman S, Jorm L, Armstrong B, Bauman A, et al. Cohort profile: the 45 and up study. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(5):941–7.

Bleicher K, Summerhayes R, Baynes S, Swarbrick M, Navin Cristina T, Luc H, et al. Cohort Profile Update: The 45 and Up Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2022:dyac104. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyac104.

Sax Institute. The 45 and Up Study Baseline Questionnaires. https://www.saxinstitute.org.au/our-work/45-up-study/questionnaires/. Accessed 20 Apr 2021.

Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority. Classification of diseases and interventions. https://www.ihacpa.gov.au/health-care/classification/icd-10-amachiacs. Accessed 16 Sept 2021.

NSW Ministry of Health. Centre for Health Record Linkage. https://www.cherel.org.au/. Accessed 16 Sept 2021.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 1270.0.55.005 - Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): Volume 5 - Remoteness Structure, July 2016. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/1270.0.55.005. Accessed 10 Sept 2021.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2033.0.55.001 - Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/2033.0.55.001~2016~Main%20Features~SEIFA%20Basics~5. Accessed 16 Sept 2021.

Haley SM, McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr. Evaluation of the MOS SF-36 physical functioning scale (PF-10): I. Unidimensionality and reproducibility of the Rasch item scale. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(6):671–84.

Stewart A, Ware J. Measuring functioning and well-being: the medical outcomes study approach: Duke University Press. 1992.

Sundararajan V, Henderson T, Perry C, Muggivan A, Quan H, Ghali WA. New ICD-10 version of the Charlson comorbidity index predicted in-hospital mortality. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(12):1288–94.

Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, Fushimi K, Graham P, Hider P, et al. Updating and Validating the Charlson Comorbidity Index and Score for Risk Adjustment in Hospital Discharge Abstracts Using Data From 6 Countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–82.

Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the Analysis of Survival Data in the Presence of Competing Risks. Circulation. 2016;133(6):601–9.

Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496–509.

Cancer Council Australia. Clinical practice guidelines for surveillance colonoscopy. 2018. https://wiki.cancer.org.au/australia/Guidelines:Colorectal_cancer/Colonoscopy_surveillance. Accessed 3 Mar 2022.

Latouche A, Allignol A, Beyersmann J, Labopin M, Fine JP. A competing risks analysis should report results on all cause-specific hazards and cumulative incidence functions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(6):648–53.

Putter H, Fiocco M, Geskus RB. Tutorial in biostatistics: competing risks and multi-state models. Stat Med. 2007;26(11):2389–430.

Lunn M, McNeil D. Applying Cox regression to competing risks. Biometrics. 1995;51(2):524–32.

Cancer Institute NSW. Cancer Statistics NSW. https://www.cancer.nsw.gov.au/research-and-data/cancer-data-and-statistics/cancer-statistics-nsw#//analysis/incidence/. Accessed 7 Apr 2022.

Australian Government Cancer Australia. National Cancer Control Indicator. Relative survival by stage at diagnosis (colorectal cancer). https://ncci.canceraustralia.gov.au/outcomes/relative-survival-rate/relative-survival-stage-diagnosis-colorectal-cancer. Accessed 7 Apr 2022.

Baxter NN, Kennedy EB, Bergsland E, Berlin J, George TJ, Gill S, et al. Adjuvant Therapy for Stage II Colon Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(8):892–910.

Cancer Research UK. Cancer waiting times. 2021. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cancer-in-general/treatment/access-to-treatment/waiting-times-after-diagnosis. Accessed 9 Oct 2021.

Richards M, Anderson M, Carter P, Ebert BL, Mossialos E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care. Nat Cancer. 2020;1(6):565–7.

Jazieh AR, Akbulut H, Curigliano G, Rogado A, Alsharm AA, Razis ED, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Cancer Care: A Global Collaborative Study. JCO Global Oncol. 2020;6:1428–38.

Brown KGM, Solomon MJ, Mahon K, O’Shannassy S. Management of colorectal cancer. BMJ. 2019;366:l4561.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Bowel Cancer Screening Program monitoring report. 2021. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer-screening/nbcsp-monitoring-report-2021/summary. Accessed 10 Apr 2021.

Lew JB, St John DJB, Xu XM, Greuter MJE, Caruana M, Cenin DR, et al. Long-term evaluation of benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program in Australia: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(7):e331–40.

Sedrak MS, Freedman RA, Cohen HJ, Muss HB, Jatoi A, Klepin HD, et al. Older adult participation in cancer clinical trials: A systematic review of barriers and interventions. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):78–92.

Millan M, Merino S, Caro A, Feliu F, Escuder J, Francesch T. Treatment of colorectal cancer in the elderly. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015;7(10):204–20.

Banks E, Jorm L, Lujic S, Rogers K. Health, ageing and private health insurance: baseline results from the 45 and Up Study cohort. Aust N Z Health Policy. 2009;6:17.

Worthington J, Feletto E, Lew JB, Broun K, Durkin S, Wakefield M, et al. Evaluating health benefits and cost-effectiveness of a mass-media campaign for improving participation in the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program in Australia. Public Health. 2020;179:90–9.

Lew J-B, St. John DJB, Macrae FA, Emery JD, Ee HC, Jenkins MA, et al. Evaluation of the benefits, harms and cost-effectiveness of potential alternatives to iFOBT testing for colorectal cancer screening in Australia. Int J Cancer. 2018;143(2):269–82.

Lew J-B, St John DJB, Macrae FA, Emery JD, Ee HC, Jenkins MA, et al. Benefits, Harms, and Cost-Effectiveness of Potential Age Extensions to the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program in Australia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(12):1450–61.

Cenin DR, St John DJ, Ledger MJ, Slevin T, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I. Optimising the expansion of the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program. Med J Aust. 2014;201(8):456–61.

Schell D, Ullah S, Brooke-Smith ME, Hollington P, Yeow M, Karapetis CS, et al. Gastrointestinal Adenocarcinoma Incidence and Survival Trends in South Australia, 1990–2017. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(2):275.

Acknowledgements

This research was completed using data collected through the 45 and Up Study (www.saxinstitute.org.au). The 45 and Up Study is managed by the Sax Institute in collaboration with major partner Cancer Council NSW; and partners: the Heart Foundation; NSW Ministry of Health; NSW Department of Communities and Justice; and Australia Red Cross Lifeblood. We thank the many thousands of people participating in the 45 and Up Study, the Centre for Health Record Linkage for the record linkage and Services Australia, the NSW Ministry of Health and Cancer Institute NSW for the use of their data. We thank Dianne O’Connell for contributing to the study design, interpretation of data and editing of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) - Preventive and Public Health Initiative - 2019 Target Health System and Community Organisation Research Grant Opportunity (grant number: MRFF1200535). KC and JBL is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (APP1194679 and APP1194784, respectively). The funders had no involvement in the design, analysis, interpretation or publishing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SY contributed to the design, conducted the analysis and interpreted the data, and wrote the initial manuscript. JS contributed to the conception and design, guided the analyses and interpretation of data, and the writing of the initial manuscript. EF contributed to the conception, design, interpretation of data and editing of the manuscript. KC contributed to the conception, interpretation of data and editing of the manuscript. EH, SE, DEG, JBL, PJN, JW, HR, JZ, JC and RLW contributed to the design, interpretation of data and editing of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The conduct of the 45 and Up Study was approved by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee. The conduct of this study was approved by the NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee (approval number 2014/08/551). 45 and Up Study participants gave written informed consent to take part in the study, including consent to follow-up through repeated data collection, linkage of their data to routinely collected population-wide health databases and publication of study data. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

SY, EH , SE, DEG, JBL, PJN, JW, HR, JC, RLW, EF, and JS have no competing interests to declare.

KC is co-PI of an investigator-initiated trial of cervical screening, Compass, run by the Australian Centre for Prevention of Cervical Cancer (ACPCC), which is a government-funded not-for-profit charity; the ACPCC has received equipment and a funding contribution from Roche Molecular Diagnostics, and operational support from the Australian Government. She is also co-PI on a major investigator-initiated implementation program Elimination of Cervical Cancer in the Western Pacific (ECCWP) which will receive support from the Minderoo Foundation, the Frazer Family Foundation and equipment donations from Cepheid Inc. Neither Karen Canfell nor her institution on her behalf receives direct funding from industry for any project. No other conflicts of interest are declared.

JZ has a leadership role at the ICON Group; owns stock in Biomarin, Opthea, Amarin Corporation, Concert Pharmaceuticals, Frequency Therapeutics, Gilead Sciences, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals, UniQure, Zogenix, Orphazyme, Moderna Therapeutics, Twist Bioscience and Novavax; has received honoraria from Specialised Therapeutics, Merck Serono, Targovax, Halozyme, Gilead Sciences, and Deciphera; serves in an advisory/consultancy role for Merck Serono, Targovax, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Halozyme, Lipotek, Specialized Therapeutics, CEND Therapeutics, Deciphera, Revolution Medicine, FivePHusion, Genor Biopharma, Globe Health Institute and Novotech; and his institution has received research funding from Merck Serono, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, IQvia, Mylan, Ipsen, Eisai, Medtronic, and MSD Oncology; and has received travel, accommodations, expenses from Merck Serono, AstraZeneca, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Deciphera and Sanofi.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Diagnosis codes used to identify conditions in the Admitted Patient Data Collection and derive Charlson’s comorbidity index score. The total index score was calculated as the total sum of updated weights for conditions captured in the 5 years prior to diagnosis.

Additional file 2.

Codes used to identify cancer treatment procedures in the different health datasets.

Additional file 3.

Colon and rectal cancer cases assigned to each treatment category based on treatment received in the 0-1, 0-2, and 0-5 years after diagnosis, by spread of disease.

Additional file 4.

Characteristics of colon cancer and rectal cancer cases by type of cancer treatment received in the 0-2 years after diagnosis.

Additional file 5.

Detailed information on the subdistribution, separate Cox’s cause-specific and joint Cox hazard model and application of each method using the SAS procedure PHREG.

Additional file 6.

Selection of colon and rectal cancer cases from the 45 and Up Study cohort for inclusion in this study.

Additional file 7.

Age and spread of disease at diagnosis of colon and rectal cancer cases in the 45 and Up Study, and of all cases in NSW and Australia.

Additional file 8.

Overall 1-, 2-, 3- and 5-year survival after a diagnosis of colon or rectal cancer, by spread of disease, based on RBDM data to June 2017.

Additional file 9.

Cancer-specific 1- and 2-year survival after a diagnosis of colon or rectal cancer, by spread of disease, based on NSWCR data to 31 December 2013.

Additional file 10.

Time from diagnosis to first cancer treatment received in the 0-2 years after diagnosis, by treatment category. The cumulative percentage was obtained using the cumulative incidence function (CIF).

Additional file 11.

Time from diagnosis to first cancer treatment received in the 0-2 years after diagnosis, by spread of disease. The cumulative percentage was obtained using the empirical cumulative distribution function (ECDF).

Additional file 12.

Multivariable adjusted hazard ratios for associations between characteristics of colon cancer cases and cancer treatment received within 2 years after cancer diagnosis. Subdistribution hazard ratios (SHRs) from the competing risks Fine-Gray model, and hazard ratios (HRs) from the cause-specific Cox hazard and joint Cox model were adjusted for all characteristics shown in the table. P-values with two asterisks (**) are significant after Bonferroni adjustment for 16 tests (i.e., p<0.003), while those with one asterisk (*) are significant at a nominal level of p<0.05.

Additional file 13.

Multivariable adjusted hazard ratios for associations between characteristics of rectal cancer cases and treatment received within 2 years from the cancer diagnosis. SHRs from the competing risks Fine-Gray model, and HRs from the cause-specific Cox hazard and joint Cox model were adjusted for all characteristics in the table. P-values with two asterisks (**) are significant after Bonferroni adjustment for 16 tests (i.e., p<0.003), while those with one asterisk (*) are significant at a nominal level of p<0.05.

Additional file 14.

Details on an emergency presentation prior to cancer diagnosis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yap, S., He, E., Egger, S. et al. Colon and rectal cancer treatment patterns and their associations with clinical, sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics: analysis of the Australian 45 and Up Study cohort. BMC Cancer 23, 60 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-10528-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-10528-8