Abstract

Background

The incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has been increasing among the elderly populations. Trans-arterial chemoembolization (TACE), a widely used first-line non-curative therapy for HCCs is an issue in geriatrics. We investigated the prognosis of elderly HCC patients treated with TACE and determined the factors that affect the overall survival.

Methods

We included 266 patients who were older than 65 years and had received TACE as initial treatment for HCC. We analyzed the skeletal muscle index (SMI) and visceral-to-subcutaneous fat ratio (VSR) around the third lumbar vertebrae using computed tomography scans. Muscle depletion with visceral adiposity (MDVA) was defined by falling below the median SMI and above the median VSR value sex-specifically. We evaluated the overall survival in association with MDVA and other clinical factors.

Results

The mean age was 69.9 ± 4.5 years, and 70.3% of the patients were men. According to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system, 29, 136, and 101 patients were classified as BCLC 0, A, and B stages, respectively, and 79 (29.7%) had MDVA. During the median follow-up of 4.1 years, patients with MDVA had a shorter life expectancy than those without MDVA (P = 0.007) even though MDVA group had a higher objective response rate after the first TACE (82.3% vs. 75.9%, P = 0.035). Multivariate analysis revealed that MDVA (Hazard ratio [HR] 1.515) age (HR 1.057), liver function (HR 1.078), tumor size (HR 1.083), serum albumin level (HR 0.523), platelet count (HR 0.996), tumor stage (stage A, HR 1.711; stage B, HR 2.003), and treatment response after the first TACE treatment (HR 0.680) were associated with overall survival.

Conclusions

MDVA is a critical prognostic factor for predicting survival in the elderly patients with HCC who have undergone TACE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Along with increased socio-economic development and improvement in medical care, the number of aged patients newly diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has been increasing [1, 2]. However, there is limited data regarding anti-HCC treatments for the elderly population and available evidence suggests that widely used Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status or Karnofsky Performance Status are insufficient predictors for elderly cancer patients [3, 4].

Trans-arterial chemoembolization (TACE), which involves injecting chemotherapeutic agents with embolic material to vessels that contribute to HCC, is the most frequently used treatment for HCC in real-world practice [5]. The indication of TACE is broad. TACE is the standard therapy for patients in the intermediate stage of HCC [6, 7], whereas for patients with early-stage HCC in whom surgery or local ablation is not feasible and in patients with advanced-stage HCC, TACE is an alternative [8]. TACE techniques are diverse according to the interventional methods and chemotherapeutic agents used; accordingly, TACE is classified as 1) conventional TACE, 2) drug-eluting bead TACE (DEB-TACE), wherein chemotherapeutic agents mixed with beads embolize the feeding vessel and release the drug slowly, and 3) trans-arterial radioembolization (TARE), in which microspheres loaded with a radioisotope are delivered to the target tumor [6]. The response to TACE is often unpredictable. For example, the median survival of intermediate stage HCC patients is estimated to be 2.5 years but, it is quite different from 5 to 25 months according to the liver function, number and size of tumors, or performance status [9]. TACE can sometimes cause serious complications, such as hepatic failure, duodenal perforation, pulmonary embolism, bile duct complications, acute renal failure, leukopenia, and even death, and the effects vary from person to person [10, 11].

The importance of body composition has been emphasized for HCC patients undergoing liver resection, transplantation, and systemic chemotherapy as proper body composition improves treatment tolerance [12,13,14,15]. Reduced muscle mass decreases functional capacity, worsens the quality of life, and eventually results in poor clinical outcomes [14]. Increased visceral adiposity is associated with insulin resistance and inflammation-promoting carcinogenesis [15]. However, the prognostic role of body composition for TACE, particularly in the aged population, is controversial [16,17,18].

It is often challenging for clinicians to make treatment plans, considering the relatively shorter life expectancy of older patients and the high possibility of serious adverse events because evidence regarding the safety and efficacy of TACE for older HCC patients is limited. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to investigate the factors affecting the survival of HCC patients over 65 years of age who were treated with TACE, with special focus on their body composition, as an objective health status evaluation method.

Methods

Patients

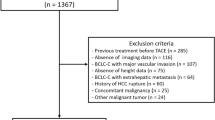

In this retrospective study, we screened the data of 649 HCC patients, aged 65 years or older, who were treated at the Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Republic of Korea, between January 2007 and December 2015, and followed up until December 2020. We defined “patients older than 65 years” as elderly because long-term care insurance is applicable from the age of 65 years in Korea [19]. All of these patients were treatment naïve. Among these silent HCC patients, we excluded the following: 1) 334 who were initially treated with interventions other than TACE (177 patients underwent hepatectomy; 134 patients, locoregional therapy; 13 patients, supportive care; 7 patients, systemic chemotherapy; and 3 patients, liver transplantation) and 2) 49 patients who were classified as having Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage C, advanced HCC, at the time of diagnosis. Finally, we enrolled 266 patients initially treated with TACE for HCC (Supplementary Fig. 1). The diagnosis of HCC was based on typical contrast-enhanced imaging criteria or histopathological confirmation according to global practice guidelines [6, 7]. All data were anonymized and obtained from the electronic medical records of the Asan Medical Center. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Republic of Korea (2019–0986).

Definitions of body composition

We analyzed cross-sectional computed tomography (CT) images at the third lumbar vertebra using AsanJ-Morphometry™ software to measure muscle and fat surface areas. The total abdominal muscle area included major large muscles and functional muscles, including the psoas, paraspinal, and abdominal wall muscles. We discriminated tissue using Hounsfield unit (HU) thresholds: muscle as − 29 to + 150 HU and fat as − 190 to − 30 HU (Fig. 1) [20]. The skeletal muscle index (SMI) was calculated as the total abdominal muscle area divided by the height squared in meters (cm2/m2). The visceral adipose tissue index and subcutaneous adipose tissue index were defined as the adipose tissue areas divided by the height squared in meters (cm2/m2). Muscle depletion was defined as a sex-specific SMI value less than the median value for all participants (as body composition differs greatly between the sexes). The visceral-to-subcutaneous fat ratio (VSR) was the ratio of the visceral fat area to the subcutaneous fat area. Visceral adiposity was defined as a sex-specific VSR greater than the median. Muscle depletion with visceral adiposity (MDVA) was defined as the presence of both muscle depletion and visceral adiposity. Patients were also grouped according to the body mass index (BMI). Sex-specific BMI values above the median were classified as the high BMI group and those below the median as the low BMI group.

Cross-sectional computed tomography of two patients, body composition evaluated at the third lumbar vertebral level. Two patients with similar BMI values (24.4 vs. 24.8 kg/m2); one (A) had more skeletal muscle and less visceral adiposity than the other (B) (SMI, 63.7 vs.42.9 cm2/m2; VSR, 1.01 vs. 1.83). BMI, body mass index; SMI, skeletal muscle index; VSR, visceral-to-subcutaneous fat ratio

Clinicopathological variables

The following variables were examined as clinical and pathological predictors of prognosis: 1) patient-related factors, including age; sex; and history of diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular incidence, other malignancy, renal failure needing dialysis, alcohol consumption, and smoking; 2) underlying liver disease-related factors, including laboratory data, ascites, variceal bleeding, and the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score; 3) tumor-related factors, including the number of tumors, maximal tumor size, serum alpha-fetoprotein level, infiltrative type of HCC, BCLC stage, and treatment response after the first TACE; and 4) body composition-related factors, including BMI, SMI, VSR, and the average HU of muscular and adipose tissue. Treatment response was evaluated via CT or magnetic resonance imaging 4 to 8 weeks after the first TACE according to the modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumors [21]. The objective tumor response rate (ORR) refers to the ratio of patients who have a complete or partial response [22]. To minimize inter-operator variability and enhance concordance among experts, the treatment response after TACE was evaluated by two hepatologists and two radiologists who have 7 to 20 years of experience [23].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistic for Windows, version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Baseline characteristics are presented as proportions for categorical variables and the mean ± standard deviations for continuous variables. Chi-squared analysis was used for categorical variables, and t-tests were used for continuous variables. The end date was the date of death or the date of the last follow-up. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidential intervals (CIs) for overall survival were estimated using Cox regression analysis. Variables with probability thresholds (P) < 0.05 from the univariate analysis were included in multivariate regression models and backward elimination. A multivariate P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank testing were used to analyze the overall survival data.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

The main demographic and clinical data are shown in Table 1. Of the 266 patients, 187 were male, and the mean age was 69.9 ± 4.5 years. The most common cause of HCC was hepatitis B virus (HBV, 58.3%), and the MELD score was 8.4 ± 2.3. Half of the patients (54.8%) had multiple HCCs at the time of diagnosis, and the mean of maximal HCC tumor size was 3.7 ± 2.8 cm. Most patients (96.6%) were treated with conventional TACE. Among 266 patients, 29 (11%), 136 (51%), and 101 (38%) were classified as BCLC stage 0 (very early), A (early stage), and B (indeterminate state), respectively. Body compositions according to sex are presented in Supplementary Table 1. The median for SMI were 49.6 and 43.1 for men and women, respectively, and 0.34 and 0.22 for VSR for men and women, respectively. Patients with MDVA had larger tumors than patients without MDVA (4.3 ± 3.8 vs. 3.4 ± 2.3 cm, respectively; P = 0.046). However, there were no other clinicopathological differences between the two groups.

Treatment response after TACE and overall survival

The treatment responses were evaluated by CT or MRI after the first TACE (median 46 days), and the results were shown in Table 2. The overall response rate (complete response and partial response) of the entire cohort was 77.8, and 75.9% and 82.3% in non-MDVA and MDVA groups, respectively (P = 0.035). Four patients could not undergo evaluation; one patient with MDVA diad 10 days after TACE, and 3 patients (2 with MDVA, and 1 without MDVA) were unable to get further evaluation nor anti-cancer treatment because of poor general condition.

During the median follow-up of 4.1 years (range, 2.0–6.8 years), 76.7% were dead, among which 73.8 and 83.5% were from the non-MDVA and MDVA groups (P = 0.119). The patients with MDVA had a shorter life expectancy than those without MDVA (83.5% vs. 91.4% at 1 year; 30.4% vs. 49.7% at 5 years, respectively; P = 0.007; Fig. 2). The first quartiles of both SMI and VSR groups were compared with others, and the relationship with body composition and overall survival showed significant difference (P = 0.041; Supplementary Fig. 2). Meanwhile, BMI was not related to long-term survival (P = 0.570; Supplementary Fig. 3).

The presence of MDVA (HR 1.501, P = 0.007) and the following variables were significantly associated with poor survival in the univariate analysis; increased age (HR 1.060, P < 0.001), underlying cause of liver disease (HCV, HR 1.802; other than HBV and HCV, HR 1.314, P = 0.002); presence of ascites (HR 1.910, P = 0.030); higher MELD score (HR 1.100, P < 0.001); larger size of the tumor (HR 1.060, P = 0.006); lower serum albumin level (HR 0.467, P < 0.001); lower platelet count (HR 0.996, P = 0.004); higher BCLC grade (stage A, HR 1.691; stage B, HR 2.062; P = 0.022); and poor response after first TACE (objective tumor response HR 0.614, P = 0.003) (Table 3). A further multivariate model revealed that the presence of MDVA was an independent predictor for the survival of elderly patients with HCC after TACE (HR 1.515, P = 0.009). In addition, increased age (HR 1.057, P < 0.001), higher MELD score (HR 1.078, P = 0.027), bigger tumor size (HR 1.083, P = 0.004), lower serum albumin level (HR 0.523, P < 0.001), lower platelet level (HR 0.996, P = 0.006), more advanced BCLC stage (stage A, HR 1.711; stage B, HR 2.003; P = 0.015), not obtaining objective response (HR 0.680, P = 0.023) were significant prognostic factors for short life expectancy (Table 3).

Subgroup analysis of overall survival according to the BCLC stages

Patients with BCLC stage 0 had the longest expected survival compared with those with stage A or stage B (stage 0 vs. stage A vs. stage B; 96.6% vs. 89.7% vs. 87.1% at 1 year; 69.0% vs. 44.1% vs. 36.6% at 5 years, respectively; P = 0.020) (Fig. 3).

Kaplan-Meier analysis for survival in geriatric HCC patients. Kaplan-Meier analysis for survival in geriatric HCC patients treated with TACE (A) according to the BCLC and that according to MDVA in each stage; (B) stage 0, (C) stage A, and (D) stage B. Life expectancy was different depending on the cancer stage; patients with BCLC stage 0 had the longest survival expectancy. In BCLC stages A and B, MDVA was important for survival. BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MDVA, muscle depletion with visceral adiposity; TACE, trans-arterial chemoembolization.

As shown in Fig. 3, there was no significant survival difference between MDVA and non-MDVA group in BCLC stage 0; but patients with MDVA had shorter life expectancy than non-MDVA patients in BCLC stage A and B, respectively. In BCLC stage A, the survival rates according to the presence of MDVA were 91.1% vs. 85.7% at 1 year, and 49.5% vs. 28.6% at 5 years in non-MDVA vs. MDVA patients (P = 0.038). Likewise, in BCLC stage B, non-MDVA patients showed higher survival rates (90.9% vs. 80.0% at 1 year, 42.4% vs. 25.7% at 6 years, respectively; P = 0.046). The univariate analysis also showed that MDVA was associated with survival in BCLC stage A (HR 1.562, P = 0.040) and B (HR 1.566, P = 0.048). When early to intermediate stage of HCC (BCLC stage A and B) patients are considered, those with MDVA tended to have a poorer outcome than those without MDVA even for the different cancer stages; patients with BCLC stage A with MDVA had shorter life expectancy than those with BCLC stage B without MDVA (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Discussion

We investigated the factors that affect the overall survival for newly diagnosed older HCC patients treated with TACE. We demonstrated that chronological age, poor liver function with higher MELD score, tumor size, lower albumin and platelet level, higher cancer stage, non-response to the TACE, as well as MDVA were major risk factors for poor survival outcomes. The number of older HCC patients is on the rise, but physicians have a hard time assessing the frailty or geriatric conditions of these patients. Our findings, especially MDVA, offer a more objective assessment paradigm.

TACE is a well-established treatment, but its adverse events have always been a concern for older patients as they are more vulnerable to external stresses [6, 24,25,26]. Therefore, TACE should be reserved for select patients, and the treatment should be performed using a customized approach based on the tumor stage, liver function, and health condition [27]. Simple observation of body weight or BMI in older patients have been used to evaluate the general condition; however, they are not enough to reflect the actual body composition, as patients with similar BMI do not necessarily have similar body composition. In our study, we did not find a relationship between BMI and survival probability.

In our study, MDVA was found to be an important prognostic factor in older HCC patients treated with TACE. Muscle depletion and visceral adiposity are important predictors of overall health and clinical outcomes for various diseases [14, 28, 29]. In terms of malignancies, the diminished muscle mass makes patients more vulnerable to chemotherapy toxicities [30, 31]. Liver disease and muscle wasting impact one another. Liver cirrhosis accelerates muscle wasting by altering the processes of protein turnover and energy disposal, leading to metabolic changes. It impairs immune responses, aggravates ascites, and worsens the quality of life [32,33,34]. Adipose tissue distribution is influenced by sex, age, race, diet, and physical activity levels [35, 36]. Visceral adiposity is known to be distinctly associated with metabolic syndrome, risk of cancers, and mortality [1, 37, 38]. This is because visceral adipose tissue releases pro-inflammatory factors, such as adiponectin, tumor necrosis factor, interleukin 6, and free fatty acids [39]. These substances directly flow into the liver through the portal vein, and it causes liver inflammation, cirrhosis, and even HCC [29].

One of the interesting findings of our study was that the clinical significance of MDVA to survival was maintained in the entire cohort, in each early and intermediate stage. Further, the treatment response after the first TACE was better in the MDVA than in the non-MDVA group. The objective response has substantial importance for HCC patients undergoing TACE because it correlates well to overall survival [22]. In our study, even if MDVA patients had a higher objective response rate, their survival period was shorter than non-MDVA patients. This demonstrates the importance of MDVA in geriatrics with HCC undergoing TACE. MDVA is one of the parameters of frailty [40]. As frail patients are more vulnerable to stress and have diminished physiological reserve, they suffer more from treatment-related complications and are intolerant to chemotherapy than non-frail patients [41]. Indeed, 15.2% of MDVA patients did not undergo any further anti-cancer treatment after the first TACE, while only 5.3% of non-MDVA patients underwent supportive care. Impaired immune system owing to MDVA makes patients more susceptible to infection, which is the common cause of non-cancer-related death among HCC patients [42].

In clinical practice, the BCLC staging system is widely used for predicting outcomes; however, early-stage (BCLC A) patients treated with TACE have a slightly better or similar survival rate compared with intermediate stage (BCLC B) patients treated with TACE in other studies [6, 43,44,45,46]. It suggests that there might be crucial factors, other than the BCLC stage, that affect prognosis in early- or intermediate-stage HCC patients treated with TACE. Our cohort of elderly HCC patients showed that body composition, which comprehensively reflects the geriatric health status, might be one of the important prognostic factors for HCC patients treated with TACE [13]. It demonstrates that lifestyle modification to build up the muscle and reduce visceral fat would be helpful for aged HCC patients treated with TACE, in addition to the appropriate anti-cancer treatment. Healthy lifestyle modifications for cancer patients, such as resistance training exercise or aerobic exercise, proved their role for increasing muscle mass and decreasing visceral fat [47,48,49]. In our institution, we are trying to properly manage in-hospital patients with poor body conditions. For example, we have a nutrition support team comprising doctors, nurses, and nutritionists. The team screens malnourished in-hospital patients based on the BMI as well as rapid change of body weight and makes proper interventions such as intravenous nutritional supplements and tailored diets. We also have a rehabilitation and exercise program for bed-ridden patients. We’d like to broaden this program to outpatient clinics as we do not have a clinical program for outpatients yet.

The effect of body composition of HCC patients is suggested in many studies. Muscle depletion or visceral fat was related to the prognosis of not only TACE, but also of other treatments such as hepatectomy, liver transplantation, radiofrequecy ablation, radiotherapy, or systemic chemotherapy including sorafenib [50,51,52,53,54]. A study from Germany revealed that sarcopenia, defined as psoas muscle volume divided by height square, as well as rapid reduction of muscle volume were poor prognostic factors for 56 TACE-treated HCC patients. A previous American study suggested that visceral fat density appeared to predict the 1-year survival and hepatic decompensation after treatment for 75 HCC patients who underwent TACE, although the study included a heterogenous population including various ages, tumor stages, and liver function, which might affect the visceral fat [50]. In our study, we particularly focused on 266 intermediate stage HCC patients aged 65 years or over to reduce the body composition bias, inevitably caused by disease status or age [55]. Personalized treatments are essential to deal with elderly HCC patients as tailored medicine is more fundamental than ever. It has always been a challenge to identify high-risk patients with poor outcomes. Here, we revealed the importance of body composition for TACE-treated elderly HCC patients, which helps the hepatologists to make more effective management strategies against these types of patients with HCC. Simple evaluation for MDVA would be useful to establish tailored therapeutic and intervention plans for elderly HCC patients, as MDVA status was associated with poor survival.

This study has several limitations. First, MDVA was defined by the median value within our cohort, as there is no internationally accepted standardized value. Body composition is largely different within and among populations; hence, it would be inappropriate to apply our absolute values for other races or ethnicities [56]. Second, muscle function and power are as important as muscle mass; however, these factors were omitted from the analysis, as these details were unavailable for retrospective study design [57]. We plan to further investigate muscle function and power by measuring handgrip strength and walking speed. However, there might be a concern that MDVA at the diagnosis is affected by not only general physical status but also the malignancy. For our study, all patients were early- or intermediate-stage at the time of diagnosis and they had relatively preserved liver function; hence, body composition would be more strongly influenced by geriatric conditions. The long-term clinical courses of our patients were not evaluated in this study; however, we aimed to determine the prognostic factors for survival at the time of diagnosis.

In conclusion, our results underscore the clinical implication for body composition in the elderly HCC patients undergoing TACE. Body composition, especially muscle depletion and visceral adiposity, should be considered as an important prognostic parameter in clinical practice, and increased attention to these factors might lead to better clinical outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

The raw data of the current study are not publicly available due to the protection of the participants’ personal information but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HCC:

-

hepatocellular carcinoma

- TACE:

-

trans-arterial chemoembolization

- SMI:

-

skeletal muscle index

- VSR:

-

visceral-to-subcutaneous fat ratio

- MDVA:

-

muscle depletion with visceral adiposity

- BCLC:

-

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- HU:

-

hounsfield unit

- MELD:

-

model for end-stage liver disease

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- CI:

-

confidential interval

- HBV:

-

hepatitis B virus

References

Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(17):2758–65. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983.

Kim BH, Park JW. Epidemiology of liver cancer in South Korea. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2018;24(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2017.0112.

Decoster L, Van Puyvelde K, Mohile S, Wedding U, Basso U, Colloca G, et al. Screening tools for multidimensional health problems warranting a geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: an update on SIOG recommendations. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(2):288–300. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu210.

VanderWalde N, Jagsi R, Dotan E, Baumgartner J, Browner IS, Burhenn P, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: older adult oncology, version 2.2016. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2016;14(11):1357–70. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2016.0146.

Park J-W, Chen M, Colombo M, Roberts LR, Schwartz M, Chen P-J, et al. Global patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma management from diagnosis to death: the BRIDGE study. Liver Int. 2015;35(9):2155–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.12818.

Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, Zhu AX, Finn RS, Abecassis MM, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68(2):723–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29913.

Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, Sirlin CB, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):358–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29086.

Han K, Kim JH. Transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma treatment: Barcelona clinic liver cancer staging system. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(36):10327–35. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i36.10327.

Giannini EG, Moscatelli A, Pellegatta G, Vitale A, Farinati F, Ciccarese F, Piscaglia F, Rapaccini GL, Di Marco M, Caturelli E et al: Application of the intermediate-stage subclassification to patients with untreated hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 2016, 111(1):70–77, 1, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2015.389.

Malagari K, Pomoni M, Moschouris H, Bouma E, Koskinas J, Stefaniotou A, et al. Chemoembolization with doxorubicin-eluting beads for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: five-year survival analysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2012;35(5):1119–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-012-0394-0.

Xia J, Ren Z, Ye S, Sharma D, Lin Z, Gan Y, et al. Study of severe and rare complications of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for liver cancer. Eur J Radiol. 2006;59(3):407–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.03.002.

Marasco G, Serenari M, Renzulli M, Alemanni LV, Rossini B, Pettinari I, et al. Clinical impact of sarcopenia assessment in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing treatments. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55(10):927–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-020-01711-w.

Baumgartner RN. Body composition in healthy aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;904(1):437–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06498.x.

Martin L, Birdsell L, Macdonald N, Reiman T, Clandinin MT, McCargar LJ, et al. Cancer cachexia in the age of obesity: skeletal muscle depletion is a powerful prognostic factor, independent of body mass index. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(12):1539–47. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2722.

Huffman DM, Barzilai N. Role of visceral adipose tissue in aging. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790(10):1117–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.01.008.

Kobayashi T, Kawai H, Nakano O, Abe S, Kamimura H, Sakamaki A, et al. Rapidly declining skeletal muscle mass predicts poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transcatheter intra-arterial therapies. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):756. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4673-2.

Fujita M, Takahashi A, Hayashi M, Okai K, Abe K, Ohira H. Skeletal muscle volume loss during transarterial chemoembolization predicts poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2019;49(7):778–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.13331.

Loosen SH, Schulze-Hagen M, Bruners P, Tacke F, Trautwein C, Kuhl C, et al. Sarcopenia is a negative prognostic factor in patients undergoing Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for hepatic malignancies. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(10):1503. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11101503.

Long-term care insurance act [https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/lawView.do?hseq=49788&lang=ENG].

Lee K, Shin Y, Huh J, Sung YS, Lee IS, Yoon KH, et al. Recent issues on body composition imaging for sarcopenia evaluation. Korean J Radiol. 2019;20(2):205–17. https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2018.0479.

Llovet JM, Lencioni R. mRECIST for HCC: performance and novel refinements. J Hepatol. 2020;72(2):288–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.09.026.

Vincenzi B, Di Maio M, Silletta M, D'Onofrio L, Spoto C, Piccirillo MC, et al. Prognostic relevance of objective response according to EASL criteria and mRECIST criteria in hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with loco-regional therapies: a literature-based meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133488. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133488.

Tovoli F, Renzulli M, Negrini G, Brocchi S, Ferrarini A, Andreone A, et al. Inter-operator variability and source of errors in tumour response assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(9):3611–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-018-5393-3.

European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines on nutrition in chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2019;70(1):172–93.

Chu KKW, Chok KSH. Is the treatment outcome of hepatocellular carcinoma inferior in elderly patients? World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(27):3563–71. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i27.3563.

Chung JW, Park JH, Han JK, Choi BI, Han MC, Lee HS, et al. Hepatic tumors: predisposing factors for complications of transcatheter oily chemoembolization. Radiology. 1996;198(1):33–40. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.198.1.8539401.

Takayasu K, Arii S, Ikai I, Omata M, Okita K, Ichida T, et al. Prospective cohort study of transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in 8510 patients. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(2):461–9. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.021.

Prado CM, Lieffers JR, McCargar LJ, Reiman T, Sawyer MB, Martin L, et al. Prevalence and clinical implications of sarcopenic obesity in patients with solid tumours of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(7):629–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70153-0.

Fujiwara N, Nakagawa H, Kudo Y, Tateishi R, Taguri M, Watadani T, et al. Sarcopenia, intramuscular fat deposition, and visceral adiposity independently predict the outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2015;63(1):131–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2015.02.031.

Prado CM, Baracos VE, McCargar LJ, Mourtzakis M, Mulder KE, Reiman T, et al. Body composition as an independent determinant of 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy toxicity. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(11):3264–8. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3067.

Nishikawa H, Nishijima N, Enomoto H, Sakamoto A, Nasu A, Komekado H, et al. Prognostic significance of sarcopenia in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing sorafenib therapy. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(2):1637–47. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2017.6287.

Dasarathy S, Merli M. Sarcopenia from mechanism to diagnosis and treatment in liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;65(6):1232–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2016.07.040.

Roubenoff R. Sarcopenia: effects on body composition and function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(11):1012–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/58.11.M1012.

Shiraki M, Nishiguchi S, Saito M, Fukuzawa Y, Mizuta T, Kaibori M, et al. Nutritional status and quality of life in current patients with liver cirrhosis as assessed in 2007-2011. Hepatol Res. 2013;43(2):106–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.12004.

Kyle UG, Genton L, Hans D, Karsegard L, Slosman DO, Pichard C. Age-related differences in fat-free mass, skeletal muscle, body cell mass and fat mass between 18 and 94 years. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001;55(8):663–72. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601198.

Wu CH, Yao WJ, Lu FH, Yang YC, Wu JS, Chang CJ. Sex differences of body fat distribution and cardiovascular dysmetabolic factors in old age. Age Ageing. 2001;30(4):331–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/30.4.331.

Ritchie SA, Connell JM. The link between abdominal obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;17(4):319–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2006.07.005.

Oh TH, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Yang SK, Choi KS, Chung JW, et al. Visceral obesity as a risk factor for colorectal neoplasm. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(3):411–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05125.x.

Shuster A, Patlas M, Pinthus JH, Mourtzakis M. The clinical importance of visceral adiposity: a critical review of methods for visceral adipose tissue analysis. Br J Radiol. 2012;85(1009):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr/38447238.

Bauer JM, Sieber CC. Sarcopenia and frailty: a clinician’s controversial point of view. Exp Gerontol. 2008;43(7):674–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2008.03.007.

Kirkhus L, Šaltytė Benth J, Rostoft S, Grønberg BH, Hjermstad MJ, Selbæk G, et al. Geriatric assessment is superior to oncologists’ clinical judgement in identifying frailty. Br J Cancer. 2017;117(4):470–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.202.

Couto OFM, Dvorchik I, Carr BI. Causes of death in patients with Unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(11):3285–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-007-9750-3.

Guo H, Wu T, Lu Q, Li M, Guo JY, Shen Y, et al. Surgical resection improves long-term survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma across different Barcelona clinic liver Cancer stages. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:361–9. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S152707.

Yang ZW, He W, Zheng Y, Zou RH, Liu WW, Zhang YP, et al. The efficacy and safety of long- versus short-interval transarterial chemoembolization in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer. 2018;9(21):4000–8. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.24250.

Vitale A, Burra P, Frigo AC, Trevisani F, Farinati F, Spolverato G, et al. Survival benefit of liver resection for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma across different Barcelona clinic liver Cancer stages: a multicentre study. J Hepatol. 2015;62(3):617–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.037.

Burrel M, Reig M, Forner A, Barrufet M, de Lope CR, Tremosini S, et al. Survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) using drug eluting beads. Implications for clinical practice and trial design. J Hepatol. 2012;56(6):1330–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2012.01.008.

Keilani M, Hasenoehrl T, Baumann L, Ristl R, Schwarz M, Marhold M, et al. Effects of resistance exercise in prostate cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(9):2953–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3771-z.

Zhu G, Zhang X, Wang Y, Xiong H, Zhao Y, Sun F. Effects of exercise intervention in breast cancer survivors: a meta-analysis of 33 randomized controlled trails. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:2153–68. https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S97864.

Brown JC, Zemel BS, Troxel AB, Rickels MR, Damjanov N, Ky B, et al. Dose-response effects of aerobic exercise on body composition among colon cancer survivors: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Cancer. 2017;117(11):1614–20. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.339.

Parikh ND, Zhang P, Singal AG, Derstine BA, Krishnamurthy V, Barman P, et al. Body composition predicts survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with Transarterial chemoembolization. Cancer Res Treat. 2018;50(2):530–7. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2017.156.

Imai K, Takai K, Hanai T, Ideta T, Miyazaki T, Kochi T, et al. Skeletal muscle depletion predicts the prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with Sorafenib. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(5):9612–24. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms16059612.

Kim YR, Park S, Han S, Ahn JH, Kim S, Sinn DH, et al. Sarcopenia as a predictor of post-transplant tumor recurrence after living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):7157. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25628-w.

Yeh WS, Chiang PL, Kee KM, Chang CD, Lu SN, Chen CH, et al. Pre-sarcopenia is the prognostic factor of overall survival in early-stage hepatoma patients undergoing radiofrequency ablation. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(23):e20455. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000020455.

Lee J, Cho Y, Park S, Kim JW, Lee IJ. Skeletal Muscle Depletion Predicts the Prognosis of Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treated With Radiotherapy. Front Oncol. 2019;9(1075). https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2019.01075.

Nishikawa H, Shiraki M, Hiramatsu A, Moriya K, Hino K, Nishiguchi S. Japan Society of Hepatology guidelines for sarcopenia in liver disease (1st edition): recommendation from the working group for creation of sarcopenia assessment criteria. Hepatol Res. 2016;46(10):951–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.12774.

Heymsfield SB, Peterson CM, Thomas DM, Heo M, Schuna JM Jr. Why are there race/ethnic differences in adult body mass index-adiposity relationships? A quantitative critical review. Obes Rev. 2016;17(3):262–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12358.

Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung TW, Chou MY, Iijima K, et al. Asian working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(3):300–7 e302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.12.012.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (No. HI18C1216) and by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI18C1216).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JHL, DL, and IYJ were responsible for the conception and design of the study; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and the drafting of the manuscript. KWK and YSK measured image data. JHL, JGC, and DBL performed the statistical analysis. YSL, YHC, HCL, YSL, KMK, and JHS critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We analyzed the data from Asan Medical Center, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea (No. 2019–0986) and all study protocols were conducted as approved. Owing to the retrospective nature of the study, we did not obtain informed consent from patients, but the study was conducted in accordance with the approved study protocol (IRB of Asan Medical Center, No. 2019–0986) which waived the need for an informed consent. We complied with the ethical rules for human experimentation stated in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lim, J., Kim, K.W., Ko, Y. et al. The role of muscle depletion and visceral adiposity in HCC patients aged 65 and over undergoing TACE. BMC Cancer 21, 1164 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08905-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08905-2