Abstract

Background

Over than one third (28–58%) of pregnancy-associated breast cancer (PABC) cases are characterized by positive epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2) expression. Trastuzumab anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody is still the benchmark treatment of HER2-positive breast tumors. However, FDA has categorized Trastuzumab as a category D drug for pregnant patients with breast cancer. This systemic review aims to synthesize all currently available data of trastuzumab administration during pregnancy and provide an updated view of the effect of trastuzumab on fetal and maternal outcome.

Methods

Eligible articles were identified by a search of MEDLINE bibliographic database and ClinicalTrials.gov for the period up to 01/09/2020; The algorithm consisted of a predefined combination of the words “breast”, “cancer”, “trastuzumab” and “pregnancy”. This study was performed in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines.

Results

A total of 28 eligible studies were identified (30 patients, 32 fetuses). In more than half of cases, trastuzumab was administered in the metastatic setting. The mean duration of trastuzumab administration during gestation was 15.7 weeks (SD: 10.8; median: 17.5; range: 1–32). Oligohydramnios or anhydramnios was the most common (58.1%) adverse event reported in all cases. There was a statistically significant decrease in oligohydramnios/anhydramnios incidence in patients receiving trastuzumab only during the first trimester (P = 0.026, Fisher’s exact test). In 43.3% of cases a completely healthy neonate was born. 41.7% of fetuses exposed to trastuzumab during the second and/or third trimester were born completely healthy versus 75.0% of fetuses exposed exclusively in the first trimester. All mothers were alive at a median follow-up of 47.0 months (ranging between 9 and 100 months). Of note, there were three cases (10%) of cardiotoxicity and decreased ejection fraction during pregnancy.

Conclusions

Overall, treatment with trastuzumab should be postponed until after delivery, otherwise pregnancy should be closely monitored.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pregnancy-associated breast cancer (PABC) is defined as any breast carcinoma diagnosed during pregnancy or during the first postpartum year [1]. It occurs in 1 to 3000 pregnancies while it has been estimated that up to 3% of breast cancers may be diagnosed in pregnant women [1, 2]. The incidence of PABC is also increasing due to advanced maternal age in today’s society. Median age of disease is 33 years (23–47 years), while there is a 2- to 3-fold decreased risk of PABC in women younger than 30 [1]. Interestingly enough, there is an increased incidence (54–80%) of estrogen receptor (ER) – negative tumors in pregnancy-related tumors [1]. This could be explained by downregulation of the receptors as a negative feedback effect of estrogen and progesterone upon hormonal receptor expression. The greater incidence of ER-negative breast cancer in pregnant women mainly stems from the young age of onset. However, some studies demonstrated that the percentage of ER-positive pregnancy-associated breast cancers was not significantly different from that of non-pregnant age-matched patients [3, 4]. On the other hand, epidermal growth factor receptor 2 -positive (HER2) tumors compose the 28–58% of PABC [3,4,5]. Although Elledge et al. found 7 out of 12 pregnant patients (58%) to be positive for HER2, Middleton et al. found no difference in the HER2 expression rate (28%) between pregnant and young nonpregnant women [3, 4]. Amant et al. reported an 31.8% incidence of HER2-positive tumors in pregnant women which is consistent with the results provided by Cardonick et al (27%) [6, 7]. Overall, the incidence of HER2-positive tumors was approximately equal to this of patients with breast cancer younger than 35 years old (39%), although it still remains a significant proportion [8].

Treatment of pregnant women with breast cancer represents a clinically challenging case in terms of maternal and fetal safety. Treatment of HER-2 positive PABC relies on the administration of trastuzumab anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody which remains the standard-of-care for all HER2-positive breast tumors. Trastuzumab binds HER2 on the C-terminal portion of domain IV and inhibits HER2 proteolytic cleavage and release of the extracellular domain in breast cancer cells [9]. Cells treated with trastuzumab undergo arrest during the G1 phase of the cell cycle leading to reduced proliferation. Trastuzumab exerts its antitumor activity through antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. However, our knowledge remains limited on the use and safety of trastuzumab during pregnancy because of its cytotoxic nature. Adverse effects of trastuzumab treatment include hematological and gastrointestinal disorders as well as cardiovascular effects that could potentially threaten pregnancy outcome.

In vivo studies conducted in cynomolgus monkeys at doses up to 25 times that of the weekly human maintenance dose of 2 mg/kg Herceptin revealed no evidence of harm to the fetus. However, trastuzumab transfer through the placenta has been observed during the early (days 20–50 of gestation) and late (days 120–150 of gestation) pregnancy period [10]. A warning about trastuzumab administration during pregnancy states that administration should be avoided during gestation unless it is mandatory for mother’s health. As for patients with breast cancer that become pregnant while receiving Trastuzumab or within 7 months after the last dose, close monitoring is indispensable.

The aim of this systematic review is to provide un updated consensus regarding trastuzumab administration during pregnancy after synthesizing all existing data emerging from case reports and individual cases. We previously conducted a relevant systematic review assessing exposure to trastuzumab during pregnancy that was published in 2012 [11]. Since there is new emerging evidence from additional cases during all these years, an updated review of literature would contribute to revision of existing data and reconsideration of current practice.

Methods

This systematic review was performed in accordance with PRISMA guidelines [12]. Eligible articles were identified by a search of MEDLINE bibliographic database and ClinicalTrials.gov for the period up to September 2020. The search algorithm consisted of the following keywords: (breast AND (carcinoma OR carcinomas OR cancer OR cancers OR neoplasm OR neoplasms)) AND (pregnancy OR pregnant OR gestation) AND (trastuzumab OR herceptin). In order to maximize the amount of synthesized information, we meticulously examined the reference lists of the relevant reviews and articles retrieved for potentially eligible papers. Language restrictions were not applied. All studies that examined the efficacy and safety of trastuzumab during pregnancy were eligible for this systematic review, no matter of sample size. All cases where therapeutic or spontaneous abortion occurred were excluded. In addition, articles assessing trastuzumab administration before or after the gestation period were considered ineligible. Eligible studies required the administration of trastuzumab at some point during pregnancy even if treatment commenced prior to pregnancy initiation. Moreover, reviews were ineligible, while all prospective and retrospective studies, as well as case reports, were eligible for this systematic review. In cases where overlapping publications emerging from the same study were identified, the larger size study was included. Two independently working reviewers (FZ and AA) performed the selection of studies and any disagreements were resolved by team consensus.

Data extraction comprised the following: general information (first author’s name, study year, journal, title), patient age at pregnancy, patient age at breast cancer diagnosis, histopathological diagnosis, clinical stage at times of disease and pregnancy diagnosis, treatment regimens administered during pregnancy, gestational age (GA) at trastuzumab initiation and withdrawal, gestational age at delivery, way of delivery and birth weight, adverse effects of chemotherapy during pregnancy, fetal and mother outcome. The quantitative synthesis of the all the recruited articles was divided in two parts. First, the descriptive statistics regarding the age of breast cancer patients at pregnancy and at BC diagnosis, GA at delivery, GA at breast cancer diagnosis, GA at trastuzumab administration, stage of disease, duration of trastuzumab administration during pregnancy, birth weight of the neonate and way of delivery were calculated. Second, the association between the occurrence of oligohydramnios/anhydramnios and the following parameters was examined: (1) exposure to trastuzumab during the second/third trimester (vs. exclusive exposure during the first trimester), (2) duration of trastuzumab administration (in weeks). Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 24.0 statistical software.

Results

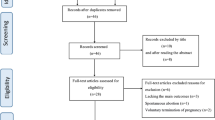

Figure 1 presents the successive steps of the selection of eligible studies. Overall, the search algorithm recruited 66 articles. Two articles were reviews examining trastuzumab administration during pregnancy [11, 13], while 31 articles were deemed irrelevant. There were 5 additional cases where the patient declined chemotherapy during pregnancy and thus treatment with trastuzumab was withhold until after delivery [14,15,16,17,18]. These articles were not eligible for our study. In a case report by Berveiller et al trastuzumab treatment was not administered during gestation and thus was excluded [19]. One article by Azim H.A. et al reported all pregnancy events in patients enrolled in HERA trial during or after exposure to trastuzumab [20]. There is no detailed information regarding each one case and therefore the study was not included in our analysis. However, this important study is discussed extensively in the discussion section. Two additional articles were retrieved from the thorough search of the reference lists of eligible articles [21, 22]. From the three clinical trials identified in ClinicalTrials.gov only one study was considered eligible (MOTHER trial), although results are not yet published [23]. Taken as a whole, 28 articles were finally included in our systematic analysis (Table 1).

Overall, 30 patients and 32 fetuses were exposed to trastuzumab during pregnancy [21, 22, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49] Table 1. Trastuzumab was administered during pregnancy as a monotherapy regimen in most cases [22, 25, 27, 28, 31, 32, 34, 36, 39, 43, 45,46,47,48] or in combination with pertuzumab [24], vinorelbine [26, 35], paclitaxel [21, 49], docetaxel [33, 41], docetaxel and carboplatin [44], tamoxifen [29, 30, 37], tamoxifen and lapatinib [42], docetaxel and cyclophosphamide [40], doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide and paclitaxel [38] and also concurrently with brain RT in one case [42]. The mean age of patients at pregnancy was 31.1 years (SD: 3.96; median: 31.5; range 23–38) [21, 22, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37, 39, 41, 43, 44, 46,47,48,49], while the mean age at breast cancer diagnosis was 29.9 years (SD: 4.21; median: 30.0; range: 22–38) [20,21,22, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37, 39, 41, 43,44,45,46, 48, 49]. In more than half of cases, trastuzumab was administered in the metastatic setting [21, 24,25,26,27, 31,32,33, 35, 38, 39, 41, 42, 45, 47,48,49], while in the remaining cases it was administered in the adjuvant setting [22, 28,29,30, 34,35,36,37, 39, 43,44,45,46].

Evaluating available histologies, invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) was diagnosed in all known cases [21, 22, 24,25,26,27, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39, 41, 43, 44, 46, 48], while in one case invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) co-existed [32]. The tumor was estrogen receptor (ER) - positive in 23% of the cases [25, 29, 30, 32, 37, 44] and progesterone receptor (PR) - positive in 20,8% of the cases [22, 25, 37, 44, 49]. Breast cancer was human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) – positive in all included cases [21, 22, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49].

The mean duration of trastuzumab administration during gestation was 15.7 weeks (SD: 10.8; median: 17.5; range: 1–32) [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39, 41, 43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. Overall, 23.3% of patients were exposed to trastuzumab during all trimesters of pregnancy [25, 27, 30,31,32, 39, 43]. Importantly, 20.0% of patients with breast cancer were exposed to trastuzumab exclusively during the first trimester [22, 34, 42, 45, 46] while trastuzumab was also administered during the second or third trimester in 80.0% of the cases [21, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41, 43,44,45, 47,48,49].

Oligohydramnios or anhydramnios was the most common (58.1%) adverse event reported in all cases [22, 24,25,26,27, 29,30,31,32,33, 35, 36, 38, 39, 43, 44, 47, 49]. Only one of the six cases (16.7%) of trastuzumab exposure exclusively during the first trimester of gestation was complicated with oligohydramnios or anhydramnios. In contrast, seventeen out of 24 pregnancies (70.8%) where trastuzumab was administered during the second or/and third trimester were complicated with oligohydramnios or anhydramnios. The difference was statistically significant (P = 0.026, Fisher’s exact test). The trend pointing to a positive association between the duration of trastuzumab treatment and the development of oligohydramnios or anhydramnios did not reach statistical significance (OR = 1.05, 95% CI: 0.96–1.14, increment: 1 week, P = 0.316).

In 67.9% of cases, delivery was performed via a cesarean section [21, 22, 25, 26, 29, 30, 32, 33, 37, 39, 41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49], while in nine pregnancies (32.1%) there a vaginal delivery occurred [27, 28, 31, 34,35,36, 38, 40, 45]. The mean gestational age at delivery was 34.6 weeks (SD: 3.26; median: 35.4; range: 27–39) [22, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49], whereas the mean birth weight at delivery was 2371 g (SD: 771.2; median: 2490; range: 1015–3820) [22, 25,26,27,28, 30,31,32,33, 35,36,37, 39,40,41, 43, 45, 46, 48, 49].

In thirteen cases (43.3%), a completely healthy neonate (thirteen out of 32 neonates) was born [21, 25, 26, 31, 33,34,35,36,37,38, 41, 45, 46]. In the remaining cases, neonates presented with: renal agenesis/hypoplasia (2 cases) [24, 47], mild transient tachypnoea (three cases) [27, 28, 48], respiratory distress syndrome (six cases) [22, 39, 40, 43, 45, 49], respiratory failure (two cases) [29, 32], renal failure (three cases) [29, 47, 49], transient respiratory failure and elevated creatinine (one case) [29], severe pulmonary hypoplasia (one case) [30], capillary leak syndrome and necrotizing enterocolitis (one case) [32], pulmonary hypertension and persistence of arterial canal (one case) [39], prematurity-related disorders (two cases) [44, 47], conductive hearing loss and mild hypertonia/hyperreflexia (one case) [45], bacterial sepsis (one case) [49] and cardiorespiratory arrest (one case) [22].

Of note, 41.7% (10 out of 24) of fetuses exposed to trastuzumab during the second and/or third trimester were born completely healthy [21, 25, 26, 31, 33, 35,36,37,38, 41] in contrast with 75.0% of fetuses exposed exclusively in the first trimester [34, 45, 46]. However, the sizeable numerical statistical significance was not achieved (P = 0.311; Fisher’s exact test). Once again, the trend pointing to a negative association between the duration of trastuzumab administration and the delivery of a completely healthy neonate did not reach statistical significance (OR = 0.921, 95% CI: 0.85–1.00, P = 0.061).

As far as maternal outcome is concerned, all patients with breast cancer were alive at a median follow-up of 47.0 months (ranging between 9 and 100 months), while only two patients relapsed during follow-up according to existing data. It should be noted that there were three cases (10%) of cardiotoxicity and decreased ejection fraction during pregnancy [21, 28, 48].

Detailed information of all eligible studies is provided in Table 1.

Discussion

PABC is a rare but complex entity which demands multidisciplinary management. Amant et al. reported similar survival rates between pregnant patients with breast cancer and the matched non-pregnant population, despite the preceding belief that PABC is associated with a poor outcome [6]. The finding that survival rates of pregnant BC patients are comparable to those of nonpregnant is essential for mother counselling and optimization of PABC management. Breast cancer treatment during pregnancy does not jeopardize maternal prognosis.

Specific guidelines have been developed for PABC treatment. Surgery is not contraindicated during pregnancy and the type of surgery chosen should be based on usual criteria (mastectomy versus breast conserving surgery) [50]. The lack of wound complications in pregnant BC patients supports surgical management of PABC. Despite the concern of milk fistulae development and that of postoperative hematoma due to the hypervascularization of the breasts, there was no apparent increase in surgical complications between pregnant and nonpregnant patients [50].

Chemotherapy should be started after the first trimester and should be stopped 2–3 weeks prior to delivery for a chemotherapy-free interval. The teratogenicity of chemotherapy depends on time of exposure, dose administered and placental transfer. During the first 2 weeks of pregnancy, spontaneous abortion is more common after chemotherapy treatment, rather than teratogenic effects on the fetus. However, as organogenesis happens from 2nd to 8th gestational week, the embryo is more vulnerable to congenital malformations during this period. The risk of chemotherapy-induced congenital malformations during the 1st trimester is 20%, whereas it declines to 1–2% during the 2nd and 3d trimester [51,52,53].

Regarding trastuzumab administration during pregnancy, we report that in approximately two third of cases oligohydramnios or anhydramnios were developed. The risk for intrauterine complications and oligohydramnios/anhydramnios development was minimal in pregnancies were fetal exposure to trastuzumab occurred exclusively during the first trimester (16.7% vs 70.8%; P = 0.026). In addition, a completely healthy neonate was born in 75% of cases that trastuzumab treatment affected only the first trimester in contrast with 41.7% of cases where the fetus was exposed during second and/or third trimester as well, although this association failed to reach statistical significance (P = 0.311; Fisher’s exact test). Our results are consistent with existing knowledge. Fetal exposure to trastuzumab is considered to be low during the first trimester while it gradually increases during the second half of gestation to reach mother levels at delivery [54]. Trastuzumab in an IgG1 monoclonal antibody with a molecular mass that does not permit transport across the placenta via simple diffusion. Active transport of these antibodies require binding to the Fc receptor of the syncytiotrophoblast, however Fc receptor is hardly detectable before the 14th week of gestation. Therefore, placental transfer of trastuzumab during the first trimester is minimal [54]. Antibody transfer to fetal endocrine organs has been reported from 4th to 6th week of development, although concentration was rather low [55]. Indeed, fetuses exposed to trastuzumab exclusively in the 1st trimester tend to be healthy at delivery. This observation is important for the correct consultation of women diagnosed with pregnancy while being on trastuzumab treatment.

US FDA has categorized Trastuzumab as a category D drug due to fetal complications [56]. No congenital malformations or teratogenic effects were reported in our review, apart from some prematurity-related problems [44, 47]. Indeed, animal studies did not reveal any teratogenic effects even at doses up to 25 times the recommended weekly human dose [56].

The most common fetal complication observed in our study was oligohydramnios or anhydramnios during second or third trimester. This is a result of EGFR receptor blockade in fetal renal epithelium by trastuzumab, where EGFR receptors are highly expressed [57]. Indeed, EGFR binding affinity in human fetal kidney between 6 and 11th GA week is 4–5 times greater than in normal renal tissue. This abundance of EGFR binding sites in fetal kidney falls rapidly in the postnatal period to low levels observed in adult renal epithelium [57]. EGF increases DNA synthesis in human fetal kidney cells, while anti-EGFR antibody leads to the opposite result. Therefore, trastuzumab attenuates the important role of EGFR receptors in fetal renal cell proliferation and nephrogenesis resulting in the aforementioned cases of oligo−/anhydramnios, fetal renal failure [29, 47, 49] and renal agenesis [24, 47] reported in our study. In addition, even in the presence of normal kidneys, this receptor blockade leads to decreased urinary output and empty fetal bladder visualization. Another explanation of the trastuzumab-induced oligohydramnios is the decreased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). VEGF regulates amniotic fluid production and absorption via modulation of the rate of intramembranous absorption of amniotic fluid by both passive and nonpassive mechanisms [58]. Trastuzumab downregulates VEGF expression and may affect the amniotic fluid level.

Another possible mechanism of trastuzumab-mediated reduction of amniotic fluid may be through altering the function of aquaporins, a family of cell membrane water channels responsible for intramembranous fluid exchange in various tissues as proposed by Sekar and Stone [33]. More specifically, Aquaporin-3 is expressed in placenta, chorion, and amnion and regulation of its expression may contribute to amniotic fluid homeostasis [59]. Moreover, it was shown that Aquaporin-8 and Aquaporin-9 levels were significantly decreased in amnion and increased in placenta in fetuses suffering from oligohydramnios, further supporting the effect of aquaporins in amniotic fluid levels [60].

Whatever the mechanism, there is increased evidence that oligohydramnios induced by trastuzumab is reversible upon discontinuation of treatment [25, 27, 29]. The mean half-life elimination time for trastuzumab weekly schedule is 6 days (range: 1–32 days) and for the 3-week schedule 16 days (range: 11–23 days) [53]. This may indicate the time required for recovery of oligo−/anhydramnios after trastuzumab treatment. Moreover, it has been shown that the risk of oligo/anhydramnios is analogous to the duration of exposure to trastuzumab during pregnancy. Trastuzumab exposure for a relatively short period does not seem to substantially affect the pregnancy outcome. In contrast, a more prolonged period of exposure is associated with increased risk of fetal harm. In our study, there was a trend to a positive association between the duration of trastuzumab treatment and the development of oligohydramnios or anhydramnios, although not statistically significant (OR = 1.05, 95% CI: 0.96–1.14, increment: 1 week, P = 0.316).

Berveiller et al. reported one case of ectopic cervico-isthmic pregnancy while on trastuzumab treatment [19]. ErbB2 is required embryo implantation process [61]. On days 1–4 ErbB2 mRNA is expressed in uterine epithelial cells, while on days 6–8 the mRNA was accumulated in both implantation and interimplantation sites [61]. Given the crucial role of HER2 in embryo implantation process, it could be postulated that trastuzumab was responsible for the incidence of this ectopic pregnancy.

Azim et al explored the effect of previous or concurrent trastuzumab administration on pregnancy outcome based on data emerging from HERA trial, one of the largest Phase III trials evaluating trastuzumab treatment in the adjuvant setting [20]. Azim et al. reported that 25% of pregnancies that occurred while on trastuzumab treatment resulted in spontaneous abortions. In consistence with our results, no congenital anomalies were reported in the study. However, there were also no cases of oligohydramnios or anhydramnios recorded in the study. The study demonstrated that women that conceived after a period of 3 months after trastuzumab cessation had an uneventful pregnancy, a finding that contributes significantly to the existing knowledge [20]. Of note, results from the very interesting MOTHER trial are anticipated [23].

Conclusions

Overall, medical oncologists encounter the dilemma of choosing between the optimal therapy for the mother and survival of the fetus. Considering that trastuzumab is equally effective when administered within 6 months from breast cancer diagnosis, it may be delayed until after delivery [62]. However, if trastuzumab administration is inevitable as in the case of metastatic disease, close monitoring of both mother and the fetus is required. It should be noted that inadvertent conception while taking Herceptin during the first trimester only is not an indication for termination.

NR: Not reported.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting our findings can be found in PubMed bibliographical database and ClinicalTrials.gov website. Links providing these data are listed below:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25853260/

https://www.wjpmr.com/home/article_abstract/1874

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30110018/

https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/abstract/10.1055/s-0035-1559647

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22381111/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21806575/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2853413/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19398090/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19274553/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18349415/

https://europepmc.org/article/med/18084047

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17666645/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16401684/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16277887/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15738038/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32729389/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31488880/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30153764/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30335191/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28255521/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26825868/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5624665/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3290009/

https://casesjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1757-1626-2-9329

https://europepmc.org/article/med/19483741

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18396008/

Change history

17 December 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-09087-7

Abbreviations

- PABC:

-

Pregnancy-associated breast cancer

- HER2:

-

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- FDA:

-

Food and drug administration

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- GA:

-

Gestational age

- BC:

-

Breast cancer

- AE:

-

Adverse event

- IDC:

-

Invasive ductal carcinoma

- ER:

-

Estrogen receptor

- PR:

-

Progesterone receptor

- ILC:

-

invasive lobular carcinoma

- DCIS:

-

Ductal carcinoma in Situ

- LNs:

-

Lymph nodes

- Gr:

-

Grade

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- CHF:

-

Congestive heart failure

- EGFR:

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- ErbB2:

-

Erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- RT:

-

Radiation therapy

- IUGR:

-

Intrauterine growth restriction

- RDS:

-

Respiratory distress syndrome

- PROM:

-

Premature rupture of membranes

- CPAP:

-

Continuous positive airway pressure

- SCN:

-

Special care nursery

- IgG1:

-

Immunoglobulin G1

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- OR :

-

Odds ratio

- SD :

-

Standard deviation

- NR:

-

Not reported

References

Navrozoglou I, Vrekoussis T, Kontostolis E, Dousias V, Zervoudis S, Stathopoulos EN, et al. Breast cancer during pregnancy: a mini-review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34(8):837–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2008.01.029.

Ring AE, Smith IE, Ellis PA. Breast cancer and pregnancy. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(12):1855–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdi388.

Elledge RM, Ciocca DR, Langone G, McGuire WL. Estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER-2/neu protein in breast cancers from pregnant patients. Cancer. 1993;71(8):2499–506. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19930415)71:8<2499::AID-CNCR2820710812>3.0.CO;2-S.

Middleton LP, Amin M, Gwyn K, Theriault R, Sahin A. Breast carcinoma in pregnant women: assessment of clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical features. Cancer. 2003;98(5):1055–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.11614.

Shousha S. Breast carcinoma presenting during or shortly after pregnancy and lactation. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124. https://doi.org/10.1043/0003-9985(2000)124<1053:BCPDOS>2.0.CO;2.

Amant F, Von Minckwitz G, Han SN, Bontenbal M, Ring AE, Giermek J, et al. Prognosis of women with primary breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy: results from an international collaborative study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(20):2532–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.45.6335.

Cardonick E, Dougherty R, Grana G, Gilmandyar D, Ghaffar S, Usmani A. Breast cancer during pregnancy: maternal and fetal outcomes. Cancer J. 2010;16(1):76–82. https://doi.org/10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181ce46f9.

Colleoni M, Rotmensz N, Robertson C, Orlando L, Viale G, Renne G, et al. Very young women (<35 years) with operable breast cancer: features of disease at presentation. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(2):273–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdf039.

Cho HS, Mason K, Ramyar KX, Stanley AM, Gabelli SB, Denney DW, et al. Structure of the extracellular region of HER2 alone and in complex with the Herceptin fab. Nature. 2003;421(6924):756–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01392.

Herceptin 150mg Powder for concentrate for solution for infusion - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc). https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/3856/smpc#gref. Accessed 12 Nov 2020.

Zagouri F, Sergentanis TN, Chrysikos D, Papadimitriou CA, Dimopoulos MA, Bartsch R. Trastuzumab administration during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137(2):349–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-012-2368-y.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. In: Journal of clinical epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol; 2009. p. e1–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006.

Goller SS, Markert UR, Fröhlich K. Trastuzumab in the treatment of pregnant breast Cancer patients - an overview of the literature. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2019;79(06):618–25. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0880-9295.

Sharma A, Nguyen HS, Lozen A, Sharma A, Mueller W. Brain metastases from breast cancer during pregnancy. Surg Neurol Int. 2016;7(24):S603–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/2152-7806.189730.

Morris PG, King F, Kennedy MJ. Cytotoxic chemotherapy for pregnancy-associated breast cancer: single institution case series. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2009;15(4):241–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078155209103096.

Pirvulescu C, Mau C, Schultz H, Sperfeld A, Isbruch A, Renner-Lützkendorf H, et al. Breast cancer during pregnancy: an interdisciplinary approach in our institution. Breast Care. 2012;7(4):311–4. https://doi.org/10.1159/000341383.

Székely B, Langmár Z, Somlai K, Szentmártoni G, Szalay K, Korompay A, et al. A várandósság alatti emlorák kezelése. Orv Hetil. 2010;151(32):1299–303. https://doi.org/10.1556/OH.2010.28886.

Yukiko Hazama, Yuichiro Nakai, Shiori Sugawara, Tsunehisa Nomura, Keiko Matsumoto, Ryou Matsumoto, et al. [A Case Report of Surgery and Chemotherapy for a Patient with Rapidly Progressing Breast Cancer during Pregnancy] - PubMed. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho . 2018;45:847–50. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30026449/. Accessed 12 Nov 2020.

Berveiller P, Mir O, Sauvanet E, Antoine EC, Goldwasser F. Ectopic pregnancy in a breast cancer patient receiving trastuzumab. Reprod Toxicol. 2008;25(2):286–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.11.004.

Azim HA, Metzger-Filho O, De Azambuja E, Loibl S, Focant F, Gresko E, et al. Pregnancy occurring during or following adjuvant trastuzumab in patients enrolled in the HERA trial (BIG 01-01). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133(1):387–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-012-1996-6.

Shweta Gupta, Prantesh Jain, Susan McDunn. Breast cancer with brain metastases in pregnancy - PubMed. J Community Support Oncol. 2014;12(10):378–80. https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0081.

Diakité K, Bouzid N, Zabroug S, Darfaoui M, Eddaoualline H, Ismaili N, Lalya I, Elomrani A, Belbaraka R, Kouchani M. The fetal toxicity of trastuzumab (herceptin) during a twin pregnancy in breast cancer: about a case. World J Pharm Med Res. 2019;5(3):187–8.

A Study of Pregnancy and Pregnancy Outcomes in Women With Breast Cancer Treated With Trastuzumab, Pertuzumab in Combination With Trastuzumab, or Ado-Trastuzumab Emtansine. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00833963.

Yildirim N, Bahceci A. Use of pertuzumab and trastuzumab during pregnancy. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2018;29(8):810–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/CAD.0000000000000658.

Rasenack R, Gaupp N, Rautenberg B, Stickeler E, Prömpeler H. Fallbericht einer Trastuzumab-Therapie während der Schwangerschaft bei metastasiertem Mammakarzinom. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2016;220(02):81–3. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1559647.

El-Safadi S, Wuesten O, Muenstedt K. Primary diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer in the third trimester of pregnancy: a case report and review of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012;38(3):589–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01745.x.

Mandrawa CL, Stewart J, Fabinyi GC, Walker SP. A case study of trastuzumab treatment for metastatic breast cancer in pregnancy: fetal risks and management of cerebral metastases. Aust New Zeal J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;51(4):372–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828X.2011.01314.x.

Roberts NJ, Auld BJ. Trastuzamab (Herceptin®)-related cardiotoxicity in pregnancy. J R Soc Med. 2010;103(4):157–9. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2009.090260.

Beale JMA, Tuohy J, McDowell SJ. Herceptin (trastuzumab) therapy in a twin pregnancy with associated oligohydramnios. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(1):e13–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2009.02.017.

Warraich Q, Smith N. Herceptin therapy in pregnancy: continuation of pregnancy in the presence of anhydramnios. J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore). 2009;29(2):147–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443610802643774.

Pant S, Landon MB, Blumenfeld M, Farrar W, Shapiro CL. Treatment of breast cancer with trastuzumab during pregnancy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(9):1567–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.16.0309.

Witzel ID, Müller V, Harps E, Janicke F, Dewit M. Trastuzumab in pregnancy associated with poor fetal outcome. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(1):191–2. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdm542.

Sekar R, Stone PR. Trastuzumab use for metastatic breast cancer in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 II):507–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000267133.65430.44.

Waterston AM, Graham J. Effect of adjuvant trastuzumab on pregnancy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(2):321–2. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.04.6607.

Fanale MA, Uyei AR, Theriault RL, Adam K, Thompson RA. Treatment of metastatic breast cancer with trastuzumab and vinorelbine during pregnancy. Clin Breast Cancer. 2005;6(4):354–6. https://doi.org/10.3816/CBC.2005.n.040.

Watson WJ. Herceptin (trastuzumab) therapy during pregnancy: association with reversible anhydramnios. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(3):642–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000141570.31218.2b.

Berwart J, Buonomo B, Peccatori FA, Marioni A, Lescano J, Pressel CE. Management of HER2-positive breast cancer during pregnancy: a case report and literature review. Tumori. 2020;106(6):NP33–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300891620944218.

Shlensky V, Hallmeyer S, Juarez L, Parilla B. Management of Breast Cancer during pregnancy: are we compliant with current guidelines? Am J Perinatol Rep. 2017;07(01):e39–43. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1599133.

De Andrade JM, Brito LGO, Moises ECD, Amorim AC, Rapatoni L, Carrara HHA, et al. Trastuzumab use during pregnancy: long-term survival after locally advanced breast cancer and long-term infant follow-up. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2016;27(4):369–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/CAD.0000000000000344.

Safi N, Anazodo A, Dickinson JE, Lui K, Wang AY, Li Z, et al. In utero exposure to breast cancer treatment: a population-based perinatal outcome study. Br J Cancer. 2019;121(8):719–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-019-0563-x.

Aktoz F, Yalcin AC, Yüzdemir HS, Akata D, Gültekin M. Treatment of massive liver metastasis of breast cancer during pregnancy: first report of a complete remission with trastuzumab and review of literature. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2020;33(7):1266–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2018.1517308.

Lambertini M, Martel S, Campbell C, Guillaume S, Hilbers FS, Schuehly U, et al. Pregnancies during and after trastuzumab and/or lapatinib in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive early breast cancer: analysis from the NeoALTTO (BIG 1-06) and ALTTO (BIG 2-06) trials. Cancer. 2019;125(2):307–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31784.

Pianca N, Shafiei M, George M. Trastuzumab exposure in early pregnancy for a young lady with locally invasive breast cancer. World J Oncol. 2015;6:381–2. https://doi.org/10.14740/wjon919w.

Gottschalk I, Berg C, Harbeck N, Stressig R, Kozlowski P. Fetal renal insufficiency following trastuzumab treatment for breast cancer in pregnancy: case report und review of the current literature. Breast Care. 2011;6(6):475–8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000335202.

Goodyer MJ, Ismail JRM, O’Reilly SP, Moylan EJ, Ryan CAM, Hughes PAF, et al. Safety of trastuzumab (Herceptin®) during pregnancy: two case reports. Cases J. 2009;2(1):9329. https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-1626-2-9329.

Azim HA, Peccatori FA, Liptrott SJ, Catania C, Goldhirsch A. Breast cancer and pregnancy: how safe is trastuzumab? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6(6):367–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.48.

Weber-Schoendorfer C, Schaefer C. Letter to the editor. Reprod Toxicol. 2008;25(3):390–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.02.002.

Shrim A, Garcia-Bournissen F, Maxwell C, Farine D, Koren G. Favorable pregnancy outcome following Trastuzumab (Herceptin®) use during pregnancy-case report and updated literature review. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;23(4):611–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.02.003.

Bader AA, Schlembach D, Tamussino KF, Pristauz G, Petru E. Anhydramnios associated with administration of trastuzumab and paclitaxel for metastatic breast cancer during pregnancy. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(1):79–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(06)71014-2.

Dominici LS, Kuerer HM, Babiera G, Hahn KME, Perkins G, Middleton L, et al. Wound complications from surgery in pregnancy-associated breast cancer (PABC). Breast Dis. 2010;31(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.3233/BD-2009-0289.

Doll DC, Ringenberg QS, Yarbro JW. Antineoplastic agents and pregnancy. Semin Oncol. 1989;16(5):337–46. https://doi.org/10.5555/uri:pii:009377548990002X.

Ebert U, Löffler H, Kirch W. Cytotoxic therapy and pregnancy. Pharmacol Ther. 1997;74(2):207–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0163-7258(97)82004-9.

NTP Monograph: Developmental Effects and Pregnancy Outcomes Associated With Cancer Chemotherapy Use During Pregnancy; NTP Monogr. 2013;(2):i–214. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24736875/.

Azim HA, Azim H, Peccatori FA. Treatment of cancer during pregnancy with monoclonal antibodies: a real challenge. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2010;6(6):821–6. https://doi.org/10.1586/eci.10.77.

Gurevich P, Elhayany A, Ben-Hur H, Moldavsky M, Szvalb S, Zandbank J, et al. An immunohistochemical study of the secretory immune system in human fetal membranes and decidua of the first trimester of pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2003;50(1):13–9. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0897.2003.01201.x.

HERCEPTIN (trastuzumab) Label – FDA. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/103792s5250lbl.pdf.

Goodyer PR, Cybulsky A, Goodyer C. Expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor in fetal kidney. Pediatr Nephrol. 1993;7(5):612–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00852567.

Cheung CY. Vascular endothelial growth factor activation of intramembranous absorption: a critical pathway for amniotic fluid volume regulation. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2004;11(2):63–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsgi.2003.09.002.

Wang S, Amidi F, Beall M, Gui L, Ross MG. Aquaporin 3 expression in human fetal membranes and its up-regulation by cyclic adenosine monophosphate in amnion epithelial cell culture. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2006;13(3):181–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsgi.2006.02.002.

Wang S, Chen J, Beall M, Zhou W, Ross MG. Expression of aquaporin 9 in human chorioamniotic membranes and placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(6):2160–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.089.

Lim H, Dey SK, Das SK. Differential expression of the erbB2 gene in the periimplantation mouse uterus: potential mediator of signaling by epidermal growth factor-like growth factors. Endocrinology. 1997;138(3):1328–37. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo.138.3.4991.

Gallagher CM, More K, Kamath T, Masaquel A, Guerin A, Ionescu-Ittu R, et al. Delay in initiation of adjuvant trastuzumab therapy leads to decreased overall survival and relapse-free survival in patients with HER2-positive non-metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;157(1):145–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-3790-3.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AA and CS searched the literature and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. KA conducted the statistical analysis. EZ and BG contributed to manuscript drafting. FZ and MAD critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript. FZ is the corresponding author and guarantor of the review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MAD has received honoraria from participation in advisory boards from Amgen, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Takeda. FZ has received honoraria for lectures and has served in an advisory role for Astra-Zeneca, Eli-Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Andrikopoulou, A., Apostolidou, K., Chatzinikolaou, S. et al. Trastuzumab administration during pregnancy: an update. BMC Cancer 21, 463 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08162-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08162-3