Abstract

Background

ATLAS evaluated the efficacy and safety of the PARP inhibitor rucaparib in patients with previously treated locally advanced/unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (UC).

Methods

Patients with UC were enrolled independent of tumor homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) status and received rucaparib 600 mg BID. The primary endpoint was investigator-assessed objective response rate (RECIST v1.1) in the intent-to-treat and HRD-positive (loss of genome-wide heterozygosity ≥10%) populations. Key secondary endpoints were progression-free survival (PFS) and safety. Disease control rate (DCR) was defined post-hoc as the proportion of patients with a confirmed complete or partial response (PR), or stable disease lasting ≥16 weeks.

Results

Of 97 enrolled patients, 20 (20.6%) were HRD-positive, 30 (30.9%) HRD-negative, and 47 (48.5%) HRD-indeterminate. Among 95 evaluable patients, there were no confirmed responses. However, reductions in the sum of target lesions were observed, including 6 (6.3%) patients with unconfirmed PR. DCR was 11.6%; median PFS was 1.8 months (95% CI, 1.6–1.9). No relationship was observed between HRD status and efficacy endpoints. Median treatment duration was 1.8 months (range, 0.1–10.1). Most frequent any-grade treatment-emergent adverse events were asthenia/fatigue (57.7%), nausea (42.3%), and anemia (36.1%). Of 64 patients with data from tumor tissue samples, 10 (15.6%) had a deleterious alteration in a DNA damage repair pathway gene, including four with a deleterious BRCA1 or BRCA2 alteration.

Conclusions

Rucaparib did not show significant activity in unselected patients with advanced UC regardless of HRD status. The safety profile was consistent with that observed in patients with ovarian or prostate cancer.

Trial registration

This trial was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03397394). Date of registration: 12 January 2018. This trial was registered in EudraCT (2017–004166-10).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bladder cancer is one of the most common cancer types [1], with urothelial carcinoma (UC) accounting for > 90% of the cases [2]. In 2018, there were approximately 549,000 estimated new bladder cancer cases and 200,000 deaths worldwide [3]. The prognosis for advanced disease is poor, with a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of only 5% in those diagnosed with distant metastases [4].

Platinum-based chemotherapy (PBC) has been the standard upfront treatment for patients with locally advanced/unresectable or metastatic UC [5]. Single chemotherapy agents, such as taxanes, gemcitabine, pemetrexed, or vinflunine (European Union only), are used in patients whose disease progressed on or after a PBC [6, 7]. However, these second-line treatments are associated with modest objective response rates (ORRs, 14–32%), with a median OS of 7–8 months [6, 8]. In the post-platinum setting, single-agent immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) have provided clinical benefit in patients with platinum-refractory UC (ORRs, 13–21%) [9, 10]. Notably, in the Keynote-045 trial, pembrolizumab demonstrated an OS advantage and a more favorable toxicity profile versus second-line chemotherapy [10]. However, many patients continue to have early progression and/or toxicity with current therapies, emphasizing the need for additional therapeutic options and research into validated biomarkers that can identify patients who are more likely to derive enduring therapeutic benefit [11, 12].

Rucaparib is a potent, oral, small-molecule inhibitor of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) enzymes [13], which play a role in DNA damage repair (DDR). Rucaparib recently received accelerated approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as single-agent therapy for patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer and is approved in the United States and the European Union for treatment or maintenance treatment of patients with recurrent ovarian cancer [14, 15]. Although data on PARP inhibitors in UC have been limited [16, 17], the following evidence suggests that a subset of urothelial tumors may be susceptible to PARP inhibition. Alterations in DDR genes (e.g. BRCA1 or BRCA2 [BRCA]) have been observed in 11% of patients with UC [18], and approximately 60% of patients with UC exhibit homologous recombination deficiency (HRD; e.g. high genome-wide loss of heterozygosity [LOH] or deleterious DDR gene alteration). Moreover, patients with UC are usually sensitive to PBC [19, 20], and platinum sensitivity in other indications has been associated with response to PARP inhibitors [21]. In clinical trials, the benefit of rucaparib was observed in both HRD-positive and HRD-negative ovarian tumors [22,23,24,25]. Based on these data, we hypothesized that rucaparib monotherapy could potentially be safe and effective in patients with locally advanced/unresectable or metastatic UC independent of tumor HRD status. Unselected enrollment of patients would also facilitate feasible accrual of patients with DDR gene alterations that are uncommon in UC, while allowing the study to be a priori powered to assess the efficacy of rucaparib in patients with HRD-positive tumors.

Here we report the final efficacy and safety results from the ATLAS study, which evaluated rucaparib in patients with locally advanced/unresectable or metastatic UC. In addition, we report the tumor genomic features of patients enrolled in this study.

Methods

Study design

ATLAS (NCT03397394; EudraCT 2017–004166-10) was an international, open-label, phase 2 study that evaluated the efficacy and safety of single-agent rucaparib for patients with locally advanced/unresectable or metastatic UC previously treated with one or two anticancer systemic regimens. The study was approved by national or local institutional review boards and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines of the International Council for Harmonisation. Patients provided written informed consent before participation.

Patients

Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years, had locally advanced/unresectable or metastatic UC with measurable disease per Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1), and had confirmed radiographic progression following one or two prior treatment regimens (e.g. cisplatin- or carboplatin-containing chemotherapy, ICI, and/or investigative agent). No more than one prior PBC was permitted for advanced disease. Patients who had never received platinum must have been ineligible for or refused cisplatin at the time of study entry. Patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1, and adequate organ function. Patients were enrolled independent of tumor HRD status as defined by genome-wide LOH [26]. However, tumor tissue collected prior to treatment was required for molecular profiling. Patients with prior PARP inhibitor treatment were excluded. Patients provided written informed consent before participating in the study. Additional inclusion criteria are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Procedures

Tumor tissue samples obtained within 28 days prior to initiating rucaparib, or within 6 months if no intervening therapy, were mandatory at baseline. If available, archival tumor samples from earlier time points were also collected. Tumor HRD status and DDR gene alterations were identified using the DX1 next-generation sequencing (NGS) assay from Foundation Medicine, Inc. (Cambridge, MA, USA) [25]. In the ARIEL2 study of rucaparib in ovarian cancer, sensitivity to platinum-containing chemotherapy and high genomic LOH (thought to be a biomarker of HRD) were associated with rucaparib benefit in ovarian cancer [25, 27]. To prospectively define HRD-positive status in the ATLAS trial, we analyzed a subset of patients from The Cancer Genome Atlas Urothelial Bladder Carcinoma (TCGA-BLCA) dataset [26] who were treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. Survival benefit was analyzed in platinum-treated patients at all possible genomic LOH cut-offs. In patients with genomic LOH ≥10%, platinum-based chemotherapy showed a statistically significant survival benefit compared to patients with genomic LOH < 10%. This cut point resulted in a favorable hazard ratio, p-value, sensitivity, and specificity. Therefore, we defined HRD-positive status as genomic LOH ≥10% for the ATLAS study.

Details of the TCGA-BLCA dataset analyses are described in the Supplementary Methods. Blood samples were also collected at baseline and various time points for circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis.

Patients received oral rucaparib 600 mg twice daily until confirmed radiographic disease progression by investigator assessment, unacceptable toxicity, or other reason for discontinuation. Dose reduction criteria are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Disease assessments were conducted by the investigator based on clinical examination and appropriate imaging technique using RECIST v1.1 [28]. The first postbaseline radiographic scan was to be performed at 8 weeks (±7 days). If a patient had signs of progression prior to the initial radiographic tumor assessment, the treating investigator could choose to perform imaging at an earlier time point. Assessments were conducted every 8 weeks for up to 18 months, then every 12 weeks thereafter, including for patients who discontinued treatment for reasons other than disease progression. Radiographic tumor assessments were continued until confirmed radiographic disease progression, loss to follow-up, withdrawal from the study, study closure, or initiation of subsequent treatment.

Patients were monitored for adverse events (AEs), serious AEs, and AEs of special interest during study participation and until 28 days after the last dose of rucaparib. AEs and laboratory abnormalities were graded according to the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grading system version 4.03 or later.

Plasma samples were collected for trough level pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis of rucaparib 1 h before the morning dose on days 29, 57, and 85.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was ORR per investigator assessment using RECIST v1.1 in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population (all patients who received ≥1 dose of rucaparib) and in patients with HRD-positive tumors. Key secondary endpoints included duration of response, progression-free survival (PFS), safety and tolerability, and the steady-state PK of rucaparib. Disease control rate (DCR), defined post-hoc as the proportion of patients with a confirmed complete or partial response, or stable disease lasting ≥16 weeks, was also assessed. Exploratory endpoints included assessing tumor tissue- and blood-based biomarkers that correlate with response to rucaparib and molecular changes over time in tumor samples. Safety was assessed by monitoring AEs and vital signs, physical examination, and laboratory testing.

Statistical analysis

ATLAS was designed to enroll approximately 200 patients. Details of sample size calculation are described in the Supplementary Methods. An adaptive study design was used, in which interim efficacy and safety analyses were performed to determine whether to continue enrollment. Two interim efficacy analyses were planned after efficacy data (defined as a documented objective response per RECIST v1.1, disease progression, or at least 4 months of disease assessments) were available for 60 and 120 patients. Enrollment was halted following the data monitoring committee’s review for the first interim analysis. We present the final results from the database lock date of February 20, 2020.

Efficacy analyses were performed using the ITT population and subgroups based on tumor HRD status (HRD-positive [genomic LOH ≥10%], HRD-negative [genomic LOH < 10%], and HRD-indeterminate). ORR and safety endpoints are summarized using descriptive statistics and PFS using Kaplan-Meier methodology. PK parameters are summarized using descriptive statistics.

Results

Patients

Ninety-seven patients were enrolled between June 1, 2018, and April 9, 2019, across 70 sites in six countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States; Fig. 1). Baseline demographics and disease characteristics of patients are provided in Table 1. Overall, 44/97 (45.4%) patients had received two prior therapies for advanced disease; 93/97 (95.9%) patients had received prior PBC, 71/97 (73.2%) patients prior ICI, and 67/97 (69.1%) patients both a PBC and an ICI (separately or combined). Of 97 patients, 77 (79.4%) provided tumor-containing tissue samples that underwent genomic testing. The majority (68/77 [88.3%]) of the samples in the analyzed dataset were obtained within 6 months of initiating rucaparib with no intervening therapy. LOH was determined for 50/97 patients (51.5%). Of 97 patients, 20 (20.6%) had HRD-positive tumors (LOH ≥10%), 30 (30.9%) HRD-negative tumors (LOH < 10%), and 47 (48.5%) indeterminate HRD status (i.e. the tumor sample was not provided or the sample quantity/quality was insufficient). The median genome-wide LOH was 8.6% (interquartile range, 5.9–12.3), consistent with data from the TCGA-BLCA dataset (10.0% [interquartile range, 5.6–14.3]; Fig. 2).

Genome-wide LOH in TCGA-BLCA dataset and tumor tissue samples. Each circle represents a tissue sample, and the bars represent the median and interquartile range. Black circles in the ATLAS dataset highlight samples with deleterious alterations in DDR pathway genes BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, or RAD51C. DDR DNA damage response; IQR interquartile range; LOH loss of heterozygosity; TCGA-BLCA The Cancer Genome Atlas Urothelial Bladder Carcinoma

By February 20, 2020, all patients had discontinued treatment, primarily due to radiographic or clinical disease progression (72/97 [74.2%]). The remaining patients discontinued due to withdrawal of consent (10/97 [10.3%]), AEs (9/97 [9.3%]), physician decision (5/97 [5.2%]), or other reason (discontinued based on new information about the effectiveness of rucaparib; 1/97 [1.0%]; Fig. 1).

After discontinuation of rucaparib, subsequent anticancer therapy was administered to 12/97 (12.4%) patients. The most frequently administered subsequent therapies were docetaxel, paclitaxel, pembrolizumab, and vinflunine, each of which was administered to 2/12 (16.7%) patients.

Efficacy outcomes

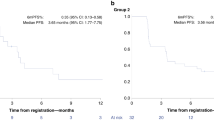

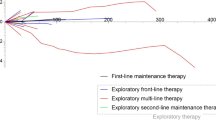

Of 97 patients enrolled, 95 had measurable disease at baseline. There were no confirmed investigator-assessed objective responses (0%; 95% CI, 0–3.8%) in the overall population or the HRD-positive subgroup. However, reductions in tumor size were observed in a number of patients, including 6/95 (6.3%) patients who had a PR that was not confirmed on subsequent tumor assessment (Fig. 3a). Tumor size reductions were observed in target lesions in lung, kidney, liver, lymph nodes (multiple anatomic sites), and peritoneal metastases, in addition to primary bladder tumors. Among these six patients, two were HRD-positive and four were HRD-indeterminate. Four of the six patients had received ICI as part of their last treatment regimen prior to rucaparib. In addition, 22/95 (23.2%) patients had a best overall response of SD, including a patient in the HRD-indeterminate subgroup with a heterozygous ATM alteration who had SD lasting 32 weeks. A similar proportion of patients across the HRD subgroups had a best overall response of SD or better (HRD-positive, 4/19 [21.1%]; HRD-negative, 7/29 [24.1%]; HRD-indeterminate, 17/47 [36.2%]).

Efficacy outcomes. Investigator-assessed best response in target lesions per RECIST v1.1 in the ITT population (a) and Kaplan-Meier estimates of progression-free survival as assessed by the investigator in the overall ITT population and HRD subgroups (b). Data cutoff: February 20, 2020. The ITT population only includes patients with measurable disease at baseline and one or more postbaseline tumor assessment (n = 69); each bar represents data from a single patient with 0% change from baseline shown as 0.5% for visual clarity; patients with a deleterious mutation in DDR pathway genes CHEK2, ATM, RAD51C, PALB2, and BRCA1 are indicated. HRD homologous recombination deficiency; ITT intent-to-treat; PFS progression-free survival; RECIST v1.1 Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1

The DCR in the overall population was 11.6% (11/95): 15.8% (3/19) in the HRD-positive subgroup, 6.9% (2/29) in the HRD-negative subgroup, and 12.8% (6/47) in the HRD-indeterminate subgroup.

Median PFS was 1.8 months (95% CI, 1.6–1.9) in the ITT population, and was similar across HRD subgroups (Fig. 3b).

Safety

The safety population included 97 patients who received ≥1 dose of rucaparib. The overall median (range) treatment duration was 1.8 months (0.1–10.1), and median (range) follow-up duration was 2.7 months (0.5–11.1).

A treatment-emergent AE (TEAE) of any grade was reported in 95/97 (97.9%) patients, the most frequent of which (≥25% of patients) were asthenia/fatigue, nausea, anemia, and decreased appetite (Table 2). Furthermore, 71/97 (73.2%) patients had a grade ≥3 TEAE; anemia and thrombocytopenia were the most frequent (Table 2). A total of 76/97 (78.4%) patients reported having at least one treatment-related AE (Supplementary Table S1). While myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia are considered AEs of special interest for rucaparib and other PARP inhibitors, no incidences of these AEs were reported.

Treatment was interrupted due to a TEAE for 50/97 (51.5%) patients, most frequently due to anemia (14/97 [14.4%]) and asthenia/fatigue (13/97 [13.4%]). Dose reduction due to a TEAE occurred in 23/97 (23.7%) patients, most commonly due to asthenia/fatigue (9/97 [9.3%]) and anemia (6/97 [6.2%]). Treatment discontinuation due to a TEAE (other than disease progression) occurred in 9/97 (9.3%) patients, with no specific TEAE reported in more than one patient. TEAEs other than disease progression resulted in death in three patients (3/97 [3.1%]): one each due to cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, and respiratory failure. All three TEAEs were considered unrelated to rucaparib. Twenty additional deaths due to disease progression were reported.

Pharmacokinetics

Mean (coefficient of variation) trough plasma concentration of rucaparib was 2130 ng/mL (86%; n = 47) at day 29, 1647 ng/mL (65%, n = 18) at day 57, and 2033 ng/mL (33%; n = 11) at day 85 (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Genomic characteristics

To better understand the genomic features of this patient population with advanced UC, genomic profiling data was generated from 64 patients with adequate tumor tissue samples (see Supplementary Methods for detailed methodology for genomic analyses). Of those collected samples, 18.8% were from the sites of primary disease (bladder, renal pelvis, or ureter) and 81.2% were from the sites of local or distant metastases, the majority of which came from lymph node, liver, and lung. The median tumor mutational burden (TMB) was 6.3 mutations/megabase (n = 60) across the entire dataset, and all samples with known status were microsatellite stable (n = 59).

Deleterious alterations in genes associated with cell cycle, fibroblast growth factor (FGF)/FGF receptor (FGFR), phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT, Ras/receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK), metabolic pathways, and chromatin remodeling pathways were frequently observed (Fig. 4). The most common genes with deleterious alterations within this patient population included the TERT promoter (75%), CDKN2A (52%), TP53 (52%), CDKN2B (50%), MTAP (38%), KDM6A (31%), CCND1 (19%), FGF19 (19%), FGFR3 (19%), MLL2 (19%), and RB1 (19%) (Fig. 4).

Genetic alterations in select pathways. Oncoprint generated from 64 tumor samples with sequencing data. Percentages shown indicate the deleterious gene alteration frequencies. *Only FGFR1 and FGFR3 alterations were identified; no FGFR2 alterations were observed. †Only one alteration type is presented when multiple alteration types were found within a single gene. ‡Includes truncating rearrangements. DDR DNA damage repair; HRD homologous recombination deficiency; PD progressive disease; PR partial response; NA not applicable; NE not evaluable; SD stable disease

In an exploratory analysis, we assessed the frequency of alterations in 15 DDR genes (ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, CDK12, CHEK2, FANCA, NBN, PALB2, RAD51, RAD51B, RAD51C, RAD51D, RAD54L). In total, 10/64 (15.6%) patients had a deleterious alteration in one of these 15 genes (three BRCA1, two ATM, two CHEK2, one each for BRCA2, PALB2, RAD51C; Supplementary Table S2). Deleterious alterations in genes that are thought to be most strongly associated with PARP inhibitor sensitivity (BRCA1, BRCA2, RAD51C, RAD51D, PALB2) were observed in 6/64 (9.4%) patients (Supplementary Table S2). Alterations in these DDR genes were not associated with the antitumor activity of rucaparib for these patients. Additional genomic data, including zygosity and germline characteristics, and co-occurring alterations, are described in the Supplementary Results.

Interestingly, five patients provided genomic data from both recent and previously obtained archival tumor tissue samples that were acquired approximately 3 months to 2 years apart (Supplementary Table S3). In the paired samples, most of the deleterious genomic alterations were present in both samples. A substantial number of novel genomic alterations were observed in the recent specimen compared to the archival sample in only one of the five patients; the interval between the two sample collections was longest for this patient (763 days).

Discussion

In the final analysis of ATLAS, although a number of patients with advanced UC had reductions in the sum of target lesions while receiving rucaparib, there were no confirmed radiographic responses. Notably, 45.4% of the patients had received two prior therapies for advanced UC. The safety and PK profile of rucaparib in patients with advanced UC were consistent with that observed in patients with ovarian, prostate, and other solid tumors [23, 30]. This suggests that the lack of observed efficacy was not likely due to changes in drug metabolism. Taken together, the results suggest that monotherapy treatment with rucaparib does not provide a meaningful benefit to unselected patients with previously-treated, advanced UC.

Among 50 ATLAS patients whose tumor tissue samples could be assessed for genomic LOH, 40% had HRD-positive tumors. Median percent genome-wide LOH of tumors from ATLAS patients was consistent with the data from TCGA-BLCA samples, suggesting that patients in this study were representative of a broader patient population with advanced UC in terms of their genomic characteristics despite the differences in the tumor sample tissue of origin (largely metastatic versus mostly primary), tumor sample heterogeneity, treatment history (one or two prior therapies versus chemotherapy-naive), and sequencing methodology (hybrid capture-based targeted gene panel versus whole-exome sequencing/single nucleotide polymorphism arrays). Many of the most frequently altered genes across the ATLAS samples also demonstrated substantial alteration frequency in the TCGA-BLCA dataset [26, 31], suggesting that many genomic alterations observed in the ATLAS patients may have occurred early in the evolution of UC. Similarly, the median TMB and microsatellite instability status of the ATLAS tumors were similar to those reported in other studies despite their inclusion of more heterogeneous samples [32, 33]. Deleterious alterations in DDR genes associated with increased sensitivity to PARP inhibitors in other tumor types (e.g. BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, RAD51C and RAD51D) were infrequent (9.4%) in ATLAS. This alteration frequency was similar to the frequencies in the TCGA-BLCA (7.9%) and in other reports in patients with UC (5.2–6.7%) [34, 35].

In clinical studies, rucaparib has shown antitumor activity in ovarian and prostate carcinomas with a deleterious germline or somatic BRCA mutation [24]. Rucaparib has also demonstrated benefit as switch maintenance treatment in patients with HRD-negative recurrent ovarian cancer [22]. However, no difference in response was observed among the HRD subgroups in our study, suggesting that tumor HRD status, as defined by genome-wide LOH, may not be a predictive biomarker of response for patients with metastatic UC. Given the small number of deleterious DDR gene alterations observed, there were insufficient data to determine a relationship between rucaparib activity and DDR gene alterations in metastatic UC. Prior research has suggested that sensitivity to PARP inhibition in patients with BRCA alterations may depend on the zygosity status of the alteration and/or tumor type [36]. Unfortunately, the significance of inactivating homozygous DDR gene alterations in metastatic UC for sensitivity to PARP inhibitor remains unclear because the majority of DDR gene alterations characterized in this study were heterozygous or the zygosity was unknown/not reported. The effect of rucaparib in multiple tumor types (including UC) with selected DDR gene alterations shown to be sensitive to PARP inhibition is being further evaluated in the LODESTAR trial (NCT04171700). Additionally, the effect of the PARP inhibitor olaparib for patients with metastatic UC with DNA-repair gene defects is being investigated in a phase 2 trial (NCT03375307).

Alterations in genes mapping to the cell cycle, RTK, TP53, PI3K, metabolic, and chromatin remodeling pathways were commonly seen in ATLAS patient samples, at frequencies similar to that in prior reports [31,32,33, 37]. Our data are in line with retrospective studies [38, 39] that assessed the landscape of genomic alterations in patients with UC who had similar characteristics to those in ATLAS. Alterations in cell cycle regulatory genes were also detected in the tumor DNA of patients enrolled in the phase Ib BISCAY trial, in which 15% of patients with UC carried an amplification in RICTOR or a deleterious alteration in TSC1/TSC2 [37]. In a phase 2 study, genomic sequencing of archival tumor tissues from patients who developed advanced UC detected frequent alterations within TP53 (52%), CDKN2A/B (34%), ARID1A (31%), and other cell cycle regulatory genes [40]. Actionable genetic alterations (e.g. PIK3CA, ERBB2, FGFR3) identified across many of these studies could possibly be targeted by various agents and may provide information about the specific outcomes of the treatment [26, 35, 39, 41]. Understanding more about the genomic landscape of advanced UC and the genomic characteristics of individual cases will aid in the development of putative biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Since the initiation of the ATLAS study, several novel agents have been approved for use in the United States in patients with previously treated metastatic UC, including targeted agents, such as erdafitinib and antibody-drug conjugates, such as enfortumab vedotin [42, 43]; the targeted agent larotrectinib has also been approved for tissue-agnostic use in the United States and European Union [44, 45]. However, more treatment options are still needed for patients with metastatic UC, including those ineligible for any platinum therapy. Olaparib had previously reported cases of activity in a small set of patients with advanced UC and a DDR gene alteration [16, 17], while ATLAS enrolled a large unselected patient population. Recent studies have evaluated ICI in combination with PARP inhibitors with the aim of improving efficacy versus ICI or PARP inhibitor monotherapy. Responses have been observed in studies evaluating olaparib with durvalumab in patients with advanced UC: a response rate of 35.7% was observed among patients with DDR gene alterations in the BISCAY trial, and a pathologic complete response rate of 44.5% was seen in a single-arm phase 2 neoadjuvant trial [37, 46]. These data suggest that PARP inhibitors in combination with ICI may have antitumor activity in patients with UC. Evaluation of PARP inhibitor monotherapy and combination treatment for patients with UC is ongoing in other trials (NCT03459846, NCT03534492, NCT02546661, and EudraCT 2015–003249-25). The recent FDA approval of avelumab (with level I evidence) as switch maintenance treatment in patients with advanced UC with response or stable disease after PBC [47, 48] may also generate new opportunities for the evaluation of PARP inhibitors as combination therapy in this disease.

ATLAS is the largest study of PARP inhibitor treatment in patients with UC to-date. However, the study had several limitations. ATLAS was a single-arm, nonrandomized study with potential bias in patient selection and confounding factors associated with patient eligibility. For example, enrolled patients had advanced disease and most had received prior PBC, which could have reduced sensitivity to subsequent PARP inhibitor treatment. It should also be noted that patients were not selected based on genomic characteristics that may have differential sensitivities to treatment with a PARP inhibitor, such as tumor HRD status, alterations in DDR pathway genes, zygosity status of specific alterations, or germline alterations. Regarding the safety profile of rucaparib, while it was overall similar to that seen with rucaparib in other tumor types, median follow-up was limited to 2.7 months. Finally, although the study had a robust biomarker program to assess putative biomarkers of sensitivity to rucaparib, tumor tissue samples were not available from all enrolled patients. In addition, not all samples were sequenced successfully because of inadequate tumor content or volume, highlighting the challenges of genomic characterization. Future NGS-based genomic profiling of ctDNA samples collected from the patients in this study just prior to the start of treatment may be a complementary approach to identify contemporaneous genomic alterations that could impact outcomes of patients with this disease [49,50,51].

Conclusions

Although rucaparib did not show confirmed responses in unselected patients with previously treated advanced UC, reductions in the sum of target lesions were observed in a number of patients. The safety profile of rucaparib in patients with advanced UC was consistent with that observed in patients with other solid tumors. Genomic profiling of tumor tissue samples has provided further insight into the molecular characterization of metastatic UC and showed that the median genome-wide LOH and deleterious genomic alterations in the ATLAS dataset were similar to the TCGA-BLCA dataset. Future studies should evaluate potential synergy of PARP inhibitors in combination with other therapies such as ICI, particularly in patients with metastatic UC associated with a DDR alteration.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

adverse event

- ALT:

-

alanine aminotransferase

- AST:

-

aspartate aminotransferase

- BRCA:

-

BRCA1 or BRCA2

- ctDNA:

-

circulating tumor DNA

- DCR:

-

disease control rate

- DDR:

-

DNA damage repair

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- ECOG PS:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- FGF:

-

fibroblast growth factor

- FGFR:

-

fibroblast growth factor receptor

- HRD:

-

homologous recombination deficiency

- ICI:

-

immune checkpoint inhibitor

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- ITT:

-

intent-to-treat

- LOH:

-

loss of heterozygosity

- NA:

-

not applicable

- NGS:

-

next-generation sequencing

- ORR:

-

objective response rate

- OS:

-

overall survival

- PARP:

-

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- PBC:

-

platinum-based chemotherapy

- PD:

-

progressive disease

- PFS:

-

progression-free survival

- PI3K:

-

phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase

- PK:

-

pharmacokinetic

- PR:

-

partial response

- RECIST v1.1:

-

Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors version 1.1

- SD:

-

stable disease

- TCGA-BLCA:

-

The Cancer Genome Atlas Urothelial Bladder Carcinoma

- TEAE:

-

treatment-emergent adverse event

- TMB:

-

tumor mutational burden

- RTK:

-

Ras/receptor tyrosine kinase

- UC:

-

urothelial carcinoma

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492.

Knowles MA, Hurst CD. Molecular biology of bladder cancer: new insights into pathogenesis and clinical diversity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;15:25–41.

World Health Organization. Cancer today. Available at https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/30-Bladder-fact-sheet.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2020.

National Cancer Institute (NCI). SEER cancer statistics factsheets: bladder cancer. Available at https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/urinb.html. Accessed March 31, 2020.

Dietrich B, Siefker-Radtke AO, Srinivas S, Yu EY. Systemic therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma: current standards and treatment considerations. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018:342–53.

Raggi D, Miceli R, Sonpavde G, Giannatempo P, Mariani L, Galsky MD, et al. Second-line single-agent versus doublet chemotherapy as salvage therapy for metastatic urothelial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(1):49–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv509.

Javlor® (vinflunine). Solution for infusion [summary of product characteristics]. Boulogne: Pierre Fabre Médicament; 2018.

Sonpavde G, Sternberg CN, Rosenberg JE, Hahn NM, Galsky MD, Vogelzang NJ. Second-line systemic therapy and emerging drugs for metastatic transitional-cell carcinoma of the urothelium. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(9):861–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70086-3.

Powles T, Duran I, van der Heijden MS, Loriot Y, Vogelzang NJ, De Giorgi U, et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (IMvigor211): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10122):748–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33297-X.

Bellmunt J, Bajorin DF. Pembrolizumab for advanced urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2304.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Bladder cancer (version 5.2020). Available at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/bladder.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2000.

Witjes J, Compérat E, Cowan N, De Santis M, Gakis G, Lebrét T, et al. EAU guidelines on muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer Available at https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/EAU-Guidelines-Muscle-invasive-and-Metastatic-Bladder-Cancer-Guidelines-2016.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2018.

Robillard L, Nguyen M, Harding T, Simmons A. In vitro and in vivo assessment of the mechanism of action of the PARP inhibitor rucaparib. Cancer Res. 2017;77(suppl 13):Abst 2475.

Rubraca® (rucaparib) tablets [prescribing information]. Boulder, CO: Clovis Oncology, Inc.; 2018.

Rubraca® (rucaparib) tablets [summary of product characteristics]. Swords: Clovis Oncology Ireland Ltd.; 2019.

Necchi A, Raggi D, Giannatempo P, Alessi A, Serafini G, Colecchia M, et al. Exceptional response to olaparib in BRCA2-altered urothelial carcinoma after PD-L1 inhibitor and chemotherapy failure. Eur J Cancer. 2018;96:128–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2018.03.021.

Sweis R, Heiss B, Segal J, Ritterhouse L, Kadri S, Churpek J, et al. Clinical activity of olaparib in urothelial bladder cancer with DNA damage response gene mutations. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;(2):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1200/PO.18.00264.

Teo MY, Bambury RM, Zabor EC, Jordan E, Al-Ahmadie H, Boyd ME, et al. DNA damage response and repair gene alterations are associated with improved survival in patients with platinum-treated advanced urothelial carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(14):3610–8. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2520.

Sternberg CN, de Mulder P, Schornagel JH, Theodore C, Fossa SD, van Oosterom AT, et al. Seven year update of an EORTC phase III trial of high-dose intensity M-VAC chemotherapy and G-CSF versus classic M-VAC in advanced urothelial tract tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(1):50–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2005.08.032.

von der Maase H, Hansen SW, Roberts JT, Dogliotti L, Oliver T, Moore MJ, et al. Gemcitabine and cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in advanced or metastatic bladder cancer: results of a large, randomized, multinational, multicenter, phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(17):3068–77. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3068.

Morgan RD, Clamp AR, Evans DGR, Edmondson RJ, Jayson GC. PARP inhibitors in platinum-sensitive high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2018;81(4):647–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-018-3532-9.

Coleman RL, Oza AM, Lorusso D, Aghajanian C, Oaknin A, Dean A, et al. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10106):1949–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32440-6.

Kristeleit R, Shapiro GI, Burris HA, Oza AM, LoRusso P, Patel MR, et al. A phase I-II study of the oral PARP inhibitor rucaparib in patients with germline BRCA1/2-mutated ovarian carcinoma or other solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(15):4095–106. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2796.

Oza AM, Tinker AV, Oaknin A, Shapira-Frommer R, McNeish IA, Swisher EM, et al. Antitumor activity and safety of the PARP inhibitor rucaparib in patients with high-grade ovarian carcinoma and a germline or somatic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation: integrated analysis of data from study 10 and ARIEL2. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;147(2):267–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.08.022.

Swisher EM, Lin KK, Oza AM, Scott CL, Giordano H, Sun J, et al. Rucaparib in relapsed, platinum-sensitive high-grade ovarian carcinoma (ARIEL2 part 1): an international, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):75–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30559-9.

Robertson AG, Kim J, Al-Ahmadie H, Bellmunt J, Guo G, Cherniack AD, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cell. 2017;171(3):540–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.007.

Konecny GE, Oza AM, Tinker AV, Coleman RL, O'Malley DM, Maloney L, et al. Rucaparib in patients with relapsed, primary platinum-sensitive high-grade ovarian carcinoma with germline or somatic BRCA mutations: integrated summary of efficacy and safety from the phase II study ARIEL2. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145:Abst 190.

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47.

Bellmunt J, Choueiri TK, Fougeray R, Schutz FA, Salhi Y, Winquist E, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract experiencing treatment failure with platinum-containing regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(11):1850–5. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4599.

Shapiro GI, Kristeleit RS, Burris HA, LoRusso P, Patel MR, Drew Y, et al. Pharmacokinetic study of rucaparib in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2019;8(1):107–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpdd.575.

National Cancer Institute (NCI). The cancer genome atlas program. Available at https://cancergenome.nih.gov/. Accessed March 17, 2020.

Chalmers ZR, Connelly CF, Fabrizio D, Gay L, Ali SM, Ennis R, et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med. 2017;9:1–14.

Necchi A, Madison R, Raggi D, Jacob JM, Bratslavsky G, Shapiro O, et al. Comprehensive assessment of immuno-oncology biomarkers in adenocarcinoma, urothelial carcinoma, and squamous-cell carcinoma of the bladder. Eur Urol. 2020;77(4):548–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2020.01.003.

Nassar AH, Abou Alaiwi S, AlDubayan SH, Moore N, Mouw KW, Kwiatkowski DJ, et al. Prevalence of pathogenic germline cancer risk variants in high-risk urothelial carcinoma. Genet Med. 2020;22(4):709–18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-019-0720-x.

Teo MY, Seier K, Ostrovnaya I, Regazzi AM, Kania BE, Moran MM, et al. Alterations in DNA damage response and repair genes as potential marker of clinical benefit from PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in advanced urothelial cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(17):1685–94. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.75.7740.

Jonsson P, Bandlamudi C, Cheng ML, Srinivasan P, Chavan SS, Friedman ND, et al. Tumour lineage shapes BRCA-mediated phenotypes. Nature. 2019;571(7766):576–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1382-1.

Powles T, Balar A, Gravis G, Jones R, Ravaud A, Florence J, et al. An adaptive, biomarker directed platform study in metastatic urothelial cancer (BISCAY) with durvalumab in combination with targeted therapies. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(suppl 5):Abst 9020.

Millis SZ, Bryant D, Basu G, Bender R, Vranic S, Gatalica Z, et al. Molecular profiling of infiltrating urothelial carcinoma of bladder and nonbladder origin. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2015;13(1):e37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clgc.2014.07.010.

Ross JS, Wang K, Khaira D, Ali SM, Fisher HA, Mian B, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of 295 cases of clinically advanced urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder reveals a high frequency of clinically relevant genomic alterations. Cancer. 2016;122(5):702–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29826.

Grivas P, Mortazavi A, Picus J, Hahn NM, Milowsky MI, Hart LL, et al. Mocetinostat for patients with previously treated, locally advanced/metastatic urothelial carcinoma and inactivating alterations of acetyltransferase genes. Cancer. 2019;125(4):533–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31817.

Van Allen EM, Mouw KW, Kim P, Iyer G, Wagle N, Al-Ahmadie H, et al. Somatic ERCC2 mutations correlate with cisplatin sensitivity in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(10):1140–53. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0623.

Padcev™ (enfortumab vedotin-ejfv) for injection. Prescribing Information. Northbrook: Astellas Pharma US, Inc.; 2019.

Balversa™ (erdafitinib) tablets. Prescribing Information. Horsham: Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies; 2019.

Vitrakvi® (larotrectinib) capsules. Prescribing Information. Horsham: Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies; 2018.

European Medicines Agency. Vitrakvi (larotrctinib). Available at https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/overview/vitrakvi-epar-medicine-overview_en.pdf. Accessed August 11, 2020.

Rodriguez-Moreno J, de Velasco G, Fernandez I, Alvarez-Fernandez C, Fernandez R, Vazquez-Estevez S, et al. Impact of the combination of durvalumab (MEDI4736) plus olaparib (AZD2281) administered prior to surgery in the molecular profile of resectable urothelial bladder cancer: NEODURVARIB Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;37(suppl 7):Abst TPS503.

Bavencio® (avelumab) injection. Prescribing Information. Rockland: EMD Serono; 2020.

Powles T, Park SH, Voog E, Caserta C, Valderrama BP, Gurney H, et al. Avelumab maintenance therapy for advanced or metastatic Urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(13):1218–30. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2002788.

Agarwal N, Pal SK, Hahn AW, Nussenzveig RH, Pond GR, Gupta SV, et al. Characterization of metastatic urothelial carcinoma via comprehensive genomic profiling of circulating tumor DNA. Cancer. 2018;124(10):2115–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31314.

Barata PC, Koshkin VS, Funchain P, Sohal D, Pritchard A, Klek S, et al. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) of cell-free circulating tumor DNA and tumor tissue in patients with advanced urothelial cancer: a pilot assessment of concordance. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(10):2458–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx405.

Grivas P, Lalani AA, Pond GR, Nagy RJ, Faltas B, Agarwal N, et al. Circulating tumor DNA alterations in advanced urothelial carcinoma and association with clinical outcomes: a pilot study. Eur Urol Oncol. 2020;3(5):695–99.

Acknowledgments

Part of the data published here (the median genome-wide LOH, deleterious alteration frequencies in DDR genes) are based upon data generated by the TCGA Research Network: https://www.cancer.gov/tcga.

Support for medical writing and copyediting was paid for by Clovis Oncology and provided by Ritu Pathak, Shelly Lim, and Frederique H. Evans of Ashfield MedComms, an Ashfield Health company.

Funding

The work was supported by Clovis Oncology (no grant number) and was designed by the sponsor, P. Grivas, and S. Chowdhury.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: PG, KW, AS, AL, DN, SC. Development of methodology: PG, KW, DT, AS, AL, RLD, DN, SC. Acquisition of data: PG, YL, RM-B, MYT, YZ, SF, NJV, EG, NA, AA, AN, AR-V, SG, DHJ, SS, SC. Analysis and interpretation of data: PG, KW, AS, AL, RLD, DN, SC. All authors participated in writing, review, and revision of the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines of the International Council for Harmonisation. Patients provided written informed consent before participation.

The study was approved by the following institutional review boards and ethics committees for participating centers: AEMPS (Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios); Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco – OsSC; AIFA (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco); ANSM (Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé); BfArM (Bundesinstitut fur Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte); CCP Ouest II (Angers); CEIm Parc de Salut Mar; Comitato Etico Area Vasta Emilia Centro; Comitato Etico della Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori; Comitato Etico Ospedale San Raffaele; Comitato Etico Universitá Federico II; DUHS IRB; Fondazione del Piemonte per l’Ongologia-IRCCS Candiolo; Georgetown University IRB; Landesärztekammer Baden-Württemberg; Medical College of Wisconsin-Froedtert Hospital IRB; Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center IRB; MHRA Regulatory Medicines and Medical Devices; NHS Health Research Authority; Oregon Health and Science IRB; Oschner Clinic Foundation IRB; Providence Health & Services IRB; Quorum; Research Compliance Office, Stanford University; Roswell Park IRB; UCLA OHRPP; University of California, San Diego Human Research Protections Program; University of Iowa IRB; University of Maryland IRB; University of Utah IRB; US Oncology, Inc. IRB; UT Health Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects; Weill Cornell Medical College IRB; WIRB (Western Institutional Review Board).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

PG has served in a consulting role for and has received fees from Clovis Oncology, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Driver, Dyania Health, EMD Serono, Exelixis, Foundation Medicine, Genentech, Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, Heron Therapeutics, Immunomedics, Infinity Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Merck, Mirati Therapeutics, Pfizer, QED Therapeutics, Roche, and Seattle Genetics; his current institution, University of Washington, received research funding from Clovis Oncology related to this study and from Bavarian Nordic, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Debiopharm, GlaxoSmithKline, Immunomedics, Kure It Cancer Research, Merck, Mirati Therapeutics, Pfizer, and QED Therapeutics unrelated to this study; and his former institution, Cleveland Clinic, received research funding from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Genentech, Merck, Mirati Therapeutics, OncoGenex, and Pfizer unrelated to this study; also acknowledges support from Seattle Translational Tumor Research Program at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. YL has served in a consulting or advisory role for Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Roche, and Seattle Genetics, and has received research funding from Johnson & Johnson, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Sanofi. RM-B has served in a consulting or advisory role and/or on the speakers bureaus for Asofarma, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Sanofi Aventis, and has received travel and accommodation expenses from Clovis Oncology, Astellas, Bayer, Janssen, Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pharmacyclics, Roche, and Sanofi Aventis. MYT has received research funding as principal investigator of clinical trials from Clovis Oncology and Bristol-Myers Squibb. YZ has served on advisory boards for Amgen, Castle Bioscience, Eisai, Exelixis, Johnson & Johnson, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche Diagnostics. SF has served on advisory boards for Aventis, Astellas, and Janssen and received travel and accommodation expenses from Aventis and Janssen. NJV has served on advisory boards for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Fuji, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, and Tolero; is on the speakers bureaus for Bayer, Exelixis, and Sanofi Aventis; has stock options in Caris; has provided legal services to Novartis; and serves on the editorial board of Up-To-Date. EG has received honoraria for advisory boards, meetings, and/or lectures from Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ipsen, Roche, Eisai, EUSA Pharma, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Sanofi-Genzyme, Adacap, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Lexicon and Celgene; has received unrestricted research grants from Pfizer, Astra Zeneca, Molecular Templates/Threshold, Roche, Ipsen, and Lexicon. NA declares no competing interests. AA has served on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Merck, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and has received research funding from Clovis Oncology, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Esanik, Genentech, Ionis, Janssen, Merck, Progenics, and Prometheus. AN has served in a consulting or advisory role for Clovis Oncology, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BioClin Therapeutics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Incyte, Janssen, Merck, and Roche, and has received research funding from AstraZeneca and Merck. AR-V has served in a consulting or advisory role and/or on the speakers bureaus for Clovis Oncology, Astellas, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, and Roche; received honoraria from AstraZeneca and Sanofi Aventis; and received research funding from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, and Takeda. SG declares no competing interests. DHJ has participated in an unbranded educational speaker program with Pfizer, and received travel and accommodation expenses from EUSA Pharma and Ipsen. SS has served in an advisory role for Clovis Oncology. KW, DT, AS, AL, RLD, and DN are employees of Clovis Oncology and may own stock or have stock options in that company. SC has served in a consulting or advisory role and/or on speakers bureaus for Clovis Oncology, Astellas Pharma, Bayer, BeiGene Janssen, Pfizer, and Sanofi; received honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis; and received research funding from Clovis Oncology, Johnson & Johnson, and Sanofi.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table S1.

Most Frequent (≥10% of Patients) Treatment-Related Adverse Events of Any Grade in the Safety Population. Supplementary Table S2. Summary of the Genetic Alterations in Tumor Tissue Samples and Tumor Responses in Patients With DDR Gene Mutation. Supplementary Table S3. Comparison of Genomic Characteristics From Archival and Recently Acquired Tumor Samples. Supplementary Figure S1. Time Profile for Mean (± Standard Deviation) Trough Plasma Concentration of Rucaparib

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Grivas, P., Loriot, Y., Morales-Barrera, R. et al. Efficacy and safety of rucaparib in previously treated, locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma from a phase 2, open-label trial (ATLAS). BMC Cancer 21, 593 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08085-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08085-z