Abstract

Background

High perioperative morbidity, mortality, and uncertain outcome of surgery in octogenarians with proximal gastric carcinoma (PGC) pose a dilemma for both patients and physicians. We aim to evaluate the risks and survival benefits of different strategies treated in this group.

Methods

Octogenarians (≥80 years) with resectable proximal gastric carcinoma who were recommended for surgery were identified from National Cancer Database during 2004–2013.

Results

Patients age ≥ 80 years with PGC were less likely to be recommended or eventually undergo surgery compared to younger patients. Patients with surgery had a significantly better survival than those without surgery (5-year OS: 26% vs. 7%, p < 0.001), especially in early stage patients. However, additional chemotherapy (HR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.82–1.08, P = 0.36) or radiotherapy (HR: 0.97, 95% CI: 0.84–1.13, P = 0.72) had limited benefits. On multivariate analysis, surgery (HR: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.51–0.86, P = 0.002) was a significant independent prognostic factor, while extensive surgery had no survival benefit (Combined organ resection: HR: 1.88, 95% CI: 1.22–2.91, P = 0.004; number of lymph nodes examined: HR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.97–1.00, P = 0.10). Surgery performed at academic and research (AR) medical center had the best survival outcome (5-year OS: 30% in AR vs. 18–27% in other programs, P < 0.001) and lowest risk (30-day mortality: 1.5% in AR vs. 3.6–6.6% in other programs, P < 0.001; 90-day mortality: 6.2% in AR vs. 13.6–16.4% in other programs, P < 0.001) compared to other facilities.

Conclusions

Less-invasive approach performed at academic and research medical center might be the optimal treatment for elderly patients aged ≥80 yrs. with early stage resectable PGC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

As the fifth most common malignancy, gastric carcinoma is the third leading cause of cancer deaths in man and fifth in women in the world [1, 2]. Gastric carcinoma is most frequently diagnosed between 65 to 74 years of age [3], with the highest percentage of deaths among people aged 75–84 years [4]. While surgery combined with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy offers the only curative treatment option, the decision to undergo an aggressive treatment approach for elderly patients is complex [5, 6]. Performance status, comorbidities, and high mortality and morbidity [7, 8], often make both patients and physicians hesitant to pursue radical surgery [9].

Previous studies have reported conflicting outcomes for patients age 80 years and older (≥80 yrs) with gastric carcinoma who undergo surgery [10,11,12,13]. A recent study utilizing data from National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) showed that advanced age (≥80 yrs) was associated with major complications and increased mortality [14]. However, studies from Asia have reported that surgery for gastric carcinoma in the elderly has acceptable perioperative morbidity and mortality [15, 16], and have further demonstrated a survival benefit of surgical resection compared to the non-operative management in elderly patients with stage I-III gastric carcinoma [17]. While most carcinomas arise in the distal stomach in Asian countries, nearly 50% of gastric carcinomas arise in the proximal stomach including cardia, fundus and gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) in Western countries [18]. Proximal gastric carcinomas often require an esophagogastrectomy with either an esophagojejunostomy or esophagogastrostomy reconstruction, which are considered to be higher risk procedures associated with higher morbidity and mortality [19,20,21]. In addition, due to variability of life expectancy, functional reserve of organ systems, social support, and personal preference, the benefit of chemotherapy and radiotherapy remains unclear [22]. As the incidence of proximal gastric carcinoma continues to rise, this is a challenging treatment dilemma that requires urgent attention [11].

Given the underrepresentation of octogenarians in clinical trials, limited evidence has been established to recommend an optimal strategy of treatment for this group of patients. Instead of evaluating the safety and efficacy of surgery between older and younger patient groups [15, 23], our study chose all octogenarians who were considered resectable (stage 0-III, and surgery was recommended by physicians), and aimed to compare the survival outcomes between different treatment strategies for this patients group.

Methods

Patient selection

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) is a joint project of the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. Based on the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Revision histology codes (ICD-O-3), patients with gastric carcinoma coded in the range of 8010–8012, 8014–8033, 8042–8148, 8170–8231, and 8252–8576 were eligible for screening in this study. With the approval of the institutional review board, 144,933 patients diagnosed with gastric carcinoma were identified between 2004 and 2013 from the NCDB. Data dictionary Participant User File (PUF) 2014 was used for reference [24]. Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index (CDCI) was used to measure the risk of the patients’ comorbidities.

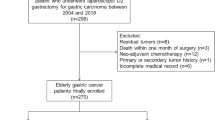

Patients aged ≥80 yrs. with proximal gastric carcinoma were selected according to the site codes of ICD-O-3 with cardia (C16.0), GEJ (C16.0) and fundus (C16.1). The potential reasons for not undergoing a cancer-related surgery were recorded in the NCDB (Surgery was not recommended by physicians or surgery was recommended by physicians but was refused by patient, patient’s family member or guardian, or patient died prior to planned surgery). Patients with stage IV disease, those who were not recommended for surgery (Surgery was not recommended/performed because it was not part of the planned first course treatment or Surgery was not recommended/performed, contraindicated due to patient risk factors) and patients with missing data of treatment strategy were excluded. The stepwise process of data extraction is depicted in Fig. 1.

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics were compared using the Pearson’s χ2 test for categorical variables and student T test for continuous variables (Age is being analyzed as a continuous variable, and interval increment is 1-year). The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate overall survival (OS) with comparison by log-rank test. Associations between potential prognostic variables and survival were estimated by Cox proportional hazard model. Other Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS package (Version 22, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All statistical tests were two-sided, with a P-value of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Overall trend of surgery in elderly patients

A total of 59,698 patients with proximal gastric carcinoma identified from NCDB were initially screened into three age groups (< 60 yrs.: n = 16,766; 60–79 yrs.: n = 32,931; and ≥ 80 yrs.: n = 10,001). Among patients age ≥ 80 yrs., 2484 patients were recommended for surgery, with a significantly decreased proportion compared to the younger age groups (Fig. 2a, ≥ 80 yrs.: 30% vs. 60–79 yrs.: 50% vs. < 60 yrs.: 50%, P < 0.001). Among patients who were recommended for surgery, the proportion who ultimately underwent surgery decreased significantly in groups age ≥ 80 yrs. (86% vs. 97% for 60–79 yrs. vs. 98% < 60 yrs. groups, P < 0.001, Fig. 2b).

Patient characteristics

A total of 2484 patients age ≥ 80 yrs. with resectable proximal gastric carcinoma identified from NCDB were eligible for the final analysis. Patients’ characteristics of the surgery group and no surgery group are summarized in Additional file 1: Table S1. Patients who underwent surgery were more likely to be younger, male gender, white race (P < 0.001). However, CDCI, tumor size, differentiation grade, and TNM stage did not significantly differ between the two groups. Patients who underwent surgery were less likely to receive chemotherapy (P < 0.001) or radiotherapy (P < 0.001). Detailed therapeutic strategies of the patients were summarized in Additional file 2: Table S2.

Survival comparison between surgical and non-surgical groups (all recommended for surgery)

For patients who were recommended for surgery, there was no significant difference in CDCI, and TNM stage between surgical and non-surgical groups. It showed that these two group patients were comparable, and the selection bias was well controlled. Our data showed that patients who underwent surgery had a significantly better survival than those who did not undergo surgery (1-year OS: 68% vs. 48%; 3-year OS: 39% vs. 15%; 5-year OS: 26% vs. 7% respectively, P < 0.001, Fig. 3a), especially in stage 0-I patients (5-year OS: 37% vs. 14%, P < 0.001, Fig. 3b). No significant difference was observed in stage II (5-year OS: 18% vs. 18%, P = 0.11, Fig. 3c) and III patients (5-year OS: 11% vs. 0%, P = 0.08, Fig. 3d). A significant survival benefit was observed in both healthy patients (CDCI score = 0, 5-year OS: 29% vs. 7%, P < 0.001, Fig. 3e) and those with comorbidities (CDCI score = 1, 5-year OS: 21% vs. 11%, P < 0.001, Fig. 3f; and CDCI score ≥ 2, 5-year OS: 18% vs. 0%, P = 0.001, Fig. 3g). Interestingly, treatment with chemotherapy or radiotherapy did not significantly impact prognosis (HR: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.80–1.01, P = 0.08 for chemotherapy, and HR: 1.00, 95% CI: 0.88–1.13, P = 0.98 for radiotherapy). After adjustment for known factors including age, gender, CDCI, tumor size, differentiation grade, TNM stage using multivariable Cox proportional hazard model, surgery (HR: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.51–0.86, P = 0.002) remained a significant independent prognostic factor for elderly surgical candidates with resectable proximal gastric carcinoma (Table 1).

Kaplan-Meier survival curve of elderly patients who did or did not undergo surgery with resectable proximal gastric carcinoma from NCDB dataset. a All elderly patients with resectable proximal gastric carcinoma. b TNM stage 0 and I subgroup of patients; c TNM stage II subgroup of patients. d TNM stage III subgroup of patients; e CDCI score 0 subgroup of patients. f CDCI score 1 subgroup of patients. g CDCI score ≥ 2 subgroup of patients. CDCI: Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index

Survival analyses in patients who underwent surgery

Univariable Cox analyses in the subgroup who underwent surgery demonstrated that older age, male gender, higher CDCI, larger tumor size, lower differentiation grade, positive lymphovascular invasion, positive surgical margin, more number of lymph nodes (LNs) examined (continuous variable), and advanced TNM stage were associated with worse overall survival (Table 2). In addition, patients who underwent surgery with combined organ resection had a significantly worse survival (HR: 1.63, 95% CI: 1.33–2.00, P < 0.001), while those who underwent local excisions had a significantly better survival (HR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.52–0.70, P < 0.001) when comparing with subtotal gastrectomy as reference. After adjustment using multivariable Cox regression, only age, CDCI, TNM stage, surgery type remained significant as independent factors for prognosis. Notably, neither chemotherapy (HR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.82–1.08, P = 0.36), radiotherapy (HR: 0.97, 95% CI: 0.84–1.13, P = 0.72) nor the sequence of treatments (HR: 1.05, 95% CI: 0.77–1.43, P = 0.76) had an impact on survival in patients undergoing surgery (Table 2).

Surgical risk and outcome related to facility

Nearly half of the elderly patients underwent surgery in academic/research program (AR-program, 992/2134, 46.5%). Compared to younger patients, 30-day and 90-day mortality rate was higher in patients age ≥ 80 yrs. (Additional file 3: Figure S1a, and S1b), however, the mortality rate was much lower for elderly patients who underwent surgery at academic and research (AR) program than that in integrated network cancer program, comprehensive community cancer program or community cancer program (30-day mortality: 1.5% in AR-program vs. 4.7, 3.6 and 6.6% in other three programs, P < 0.001; 90-day mortality: 6.2% in AR-program vs. 14.6, 13.6 and 16.4% in other three programs, P < 0.001) (Additional file 3: Figure S1c, and S1d). Consistent with the result of surgical risk, the survival outcome was also significantly better in patients underwent surgery in AR-program than those treated in integrated network cancer program, comprehensive community cancer program or community cancer program (5-year OS: 30% vs. 27% vs. 22% vs. 18% respectively, P < 0.001) (Table 2, and Additional file 4: Figure S2).

Discussion

Gastric carcinoma in the elderly patients represents a distinct entity with specific clinicopathological characteristics and treatment response. Previous studies reported that elderly patients tend to have higher American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status scores, more advanced stage, less resectability, as well as a poorer prognosis [11,12,13, 25]. On the other hand, proximal gastric carcinoma tends to be more common in elderly patients [12], and usually requires more complex and high risk procedures such as an esophagogastrectomy with esophagojejunostomy, or esophagogastrostomy. As a result, treatment strategies including surgical resection, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy are always controversial in elderly gastric carcinoma patients, especially for proximal tumors.

Most of previous studies reported similar risks and benefits of surgery for elderly GC patients when compared to their younger counterparts [25, 26], or reported comparable outcome between elderly GC patients who received surgery or not in all tumor locations [17]. However, no previous studies have focused on elderly proximal GC entity. Our study addresses this issue using the NCDB database.

We found that both the rate of surgery recommendation and the rate of surgery ultimately performed for elderly patients with proximal gastric carcinoma decreased dramatically (aged ≥80 yrs. vs. younger: 30% vs 50, and 86% vs 98%, respectively). This may be explained by that clinicians were reluctant to perform radical surgery for this group of patients due to comorbidities, high risk of perioperative morbidity and mortality, high proportion of late stage or metastasis, and short life expectancy [11]. Additionally, patients themselves may also contributed to this situation due to limited evidence of surgical benefit [27, 28].

More importantly, we found that within the group of elderly patients age ≥ 80 yrs., surgery could significantly improve OS, especially for early stage patients with resectable proximal gastric carcinoma. This finding is consistent with previous reports focusing on overall elderly patients with gastric cancer, regardless of tumor sites [17, 29, 30]. Moreover, the survival benefit of surgery was observed in both healthy and less healthy patients with certain comorbidities (CDCI ≥1), indicating that age-associated comorbidities should not be considered as absolute contraindication for surgery [13, 31, 32]. The gradually expanded indications for surgical treatment in elderly patients might attributed to the improvement of surgical techniques and postoperative intensive care treatments [33]. According to recent research, no significant differences in complications, morbidity, and hospital stay duration after surgery were found between younger patients and those older than 80 yrs. by using laparoscopy assisted gastrectomy [34]. Similar results were also reported that when surgery was performed safely, the survival rate of elderly patients was similar to that of the general population [26, 35, 36]. It is important to emphasize that our results are based on the patients who were deemed surgical candidates by treating clinicians. The treating clinicians play a pivotal role in assessing medical fitness, comorbidities, and the functional status of the elderly patient in order to determine the optimal treatment plan that will preserve the best possible quality and quantity of life [12].

Given the fear of the potential risks of surgery, it is generally claimed that elderly patients are often undertreated [37]. Although radical gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection has been widely accepted as the standard surgical approach for patient with gastric carcinoma, this aggressive approach has been questioned for elderly patients. While there are a limited number of studies reporting that higher lymph node examination could prolong survival without an increased postoperative mortality [38], most prior reports have demonstrated that extended lymph node dissection did not improve the 5-year OS of elderly patients and was associated with increased mortality and morbidity [17, 26, 39,40,41]. In our study, we found increased lymph node examination was a reverse prognostic factor, though it was not an independent risk factor in multivariable analyses. Moreover, patients undergoing extensive surgery with combined organ resection did not have an expected favorable survival outcome.

There are a few additional interesting findings from our study. We found that patients who were treated in academic or research program had a significantly lower 30-day mortality than a community cancer program. This might due to the surgical volume effect [42, 43] as shown in pancreatic surgery. The academic medical center usually has much more experience, comprehensive infrastructure and ready available services (intensive care unit, geriatric, cardiac, interventional radiology services) in taking care of complicated elderly population that usually has less physiological reserve.

In addition, while many randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated that chemotherapy may improve 5-year OS for gastric carcinoma patients [44], patients age ≥ 80 yrs. were generally excluded or underrepresented by RCTs. As a result, the usefulness of applying chemotherapy or radiotherapy in elderly patients remains controversial. Our results also indicated that chemotherapy or radiotherapy had limited benefits in this elderly group, regardless if used in neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting if they received a curative surgical resection. This result was consistent with previous small cohort studies which demonstrated that elderly patients did not benefit from neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment [45,46,47,48], especially for patients older than 80 years [49]. There are a limited number of studies that have reported a survival benefit for adjuvant chemoradiation therapy [50, 51]. The oncologic benefit of neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy must be balanced with the potentially increased toxicities and decreased quality of life in elderly patients.

As this is a large population-based study, it has several potential limitations. First, given the retrospective design, all analyses are subject to selection biases and imbalances in unquantified variables. Second, this analysis is restricted to the evaluation of OS rather than disease-specific survival, and lacks relevant information such as the postoperative complications.

Conclusions

Octogenarians with proximal gastric cancer appear to be undertreated in the US. Less-invasive approach (gastrectomy with less extensive lymph node dissection, and without joint organ resection) should be offered to patients who are considered potential surgical candidates in academic medical center, especially for those early stage patients. More evidence is needed to advocate or discourage the use of chemotherapy or radiotherapy in this group of patients.

Availability of data and materials

The data used in this study are available from National Cancer Database, which are used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. However, the statistic codes used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AR:

-

Academic and research

- CDCI:

-

Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- GC:

-

Gastric cancer

- GEJ:

-

Gastroesophageal junction

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- NCDB:

-

National cancer database

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PGC:

-

Proximal gastric cancer

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30.

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2017. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2017.

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/stomach.html, 2009-2013. Accessed 11 Nov 2019.

Dudeja V, Habermann EB, Zhong W, Tuttle TM, Vickers SM, Jensen EH, Al-Refaie WB. Guideline recommended gastric cancer care in the elderly: insights into the applicability of cancer trials to real world. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:26–33.

Biondi A, Cananzi FC, Persiani R, Papa V, Degiuli M, Doglietto GB, D'Ugo D. The road to curative surgery in gastric cancer treatment: a different path in the elderly? J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:858–67.

Al-Refaie WB, Parsons HM, Henderson WG, Jensen EH, Tuttle TM, Vickers SM, Rothenberger DA, Virnig BA. Major cancer surgery in the elderly: results from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Ann Surg. 2010;251:311–8.

Townsley C, Pond GR, Peloza B, Kok J, Naidoo K, Dale D, Herbert C, Holowaty E, Straus S, Siu LL. Analysis of treatment practices for elderly cancer patients in Ontario, Canada. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3802–10.

Eguchi T, Fujii M, Takayama T. Mortality for gastric cancer in elderly patients. J Surg Oncol. 2003;84:132–6.

Kunisaki C, Akiyama H, Nomura M, Matsuda G, Otsuka Y, Ono HA, Shimada H. Comparison of surgical outcomes of gastric cancer in elderly and middle-aged patients. Am J Surg. 2006;191:216–24.

Saif MW, Makrilia N, Zalonis A, Merikas M, Syrigos K. Gastric cancer in the elderly: an overview. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:709–17.

Lu Z, Lu M, Zhang X, Li J, Zhou J, Gong J, Gao J, Li Y, Shen L. Advanced or metastatic gastric cancer in elderly patients: clinicopathological, prognostic factors and treatments. Clin Transl Oncol. 2013;15:376–83.

Park HJ, Ahn JY, Jung HY, Lee JH, Jung KW, Kim DH, Choi KD, Song HJ, Lee GH, Kim JH, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of gastric cancer patients aged over 80 years: a retrospective case-control study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0167615.

Teng A, Bellini G, Pettke E, Passeri M, Lee DY, Rose K, Bilchik AJ, Attiyeh F. Outcomes of octogenarians undergoing gastrectomy performed for malignancy. J Surg Res. 2017;207:1–6.

Lim JH, Lee DH, Shin CM, Kim N, Park YS, Jung HC, Song IS. Clinicopathological features and surgical safety of gastric cancer in elderly patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29:1639–45.

Nakanoko T, Kakeji Y, Ando K, Nakashima Y, Ohgaki K, Kimura Y, Saeki H, Oki E, Morita M, Maehara Y. Assessment of surgical treatment and postoperative nutrition in gastric cancer patients older than 80 years. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:511–5.

Gong CS, Yook JH, Oh ST, Kim BS. Comparison of survival of surgical resection and conservative treatment in patients with gastric cancer aged 80 years or older: a single-center experience. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2016;91:219–25.

Strong VE, Song KY, Park CH, Jacks LM, Gonen M, Shah M, Coit DG, Brennan MF. Comparison of gastric cancer survival following R0 resection in the United States and Korea using an internationally validated nomogram. Ann Surg. 2010;251:640–6.

Ahn SH, Lee JH, Park DJ, Kim HH. Comparative study of clinical outcomes between laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy (LAPG) and laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy (LATG) for proximal gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:282–9.

Hoshikawa T, Denno R, Ura H, Yamaguchi K, Hirata K. Proximal gastrectomy and jejunal pouch interposition: evaluation of postoperative symptoms and gastrointestinal hormone secretion. Oncol Rep. 2001;8:1293–9.

An JY, Youn HG, Choi MG, Noh JH, Sohn TS, Kim S. The difficult choice between total and proximal gastrectomy in proximal early gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2008;196:587–91.

Balducci L, Extermann M. Management of cancer in the older person: a practical approach. Oncologist. 2000;5:224–37.

Yang JY, Lee HJ, Kim TH, Huh YJ, Son YG, Park JH, Ahn HS, Suh YS, Kong SH, Yang HK. Short- and long-term outcomes after Gastrectomy in elderly gastric cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:469–77.

Surgeons ACo: National cancer data base participant use data file (PUF) data dictionary version: PUF 2014 – containing cases diagnosed in 2004–2014. 2014.

Arai T, Esaki Y, Inoshita N, Sawabe M, Kasahara I, Kuroiwa K, Honma N, Takubo K. Pathologic characteristics of gastric cancer in the elderly: a retrospective study of 994 surgical patients. Gastric Cancer. 2004;7:154–9.

Takeshita H, Ichikawa D, Komatsu S, Kubota T, Okamoto K, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Otsuji E. Surgical outcomes of gastrectomy for elderly patients with gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2013;37:2891–8.

Sohn IW, Jung DH, Kim JH, Chung HS, Park JC, Shin SK, Lee SK, Lee YC. Analysis of the Clinicopathological characteristics of gastric cancer in extremely old patients. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49:204–12.

Roviello F, Marrelli D, De Stefano A, Messano A, Pinto E, Carli A. Complications after surgery for gastric cancer in patients aged 80 years and over. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1998;28:116–22.

Matsushita I, Hanai H, Kajimura M, Tamakoshi K, Nakajima T, Matsubayashi Y, Kanek E. Should gastric cancer patients more than 80 years of age undergo surgery? Comparison with patients not treated surgically concerning prognosis and quality of life. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:29–34.

Isobe T, Hashimoto K, Kizaki J, Miyagi M, Aoyagi K, Koufuji K, Shirouzu K. Surgical procedures, complications, and prognosis for gastric cancer in the very elderly (>85): a retrospective study. Kurume Med J. 2012;59:61–70.

Lambert R. Treatment of early gastric cancer in the elderly: leave it, cut out, peel out? Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:872–4.

Lu J, Huang CM, Zheng CH, Li P, Xie JW, Wang JB, Lin JX, Chen QY, Cao LL, Lin M. Short- and long-term outcomes after laparoscopic versus open Total Gastrectomy for elderly gastric cancer patients: a propensity score-matched analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1949–57.

Lee SR, Kim HO, Yoo CH. Impact of chronologic age in the elderly with gastric cancer. J Korean Surg Soc. 2012;82:211–8.

Yamada H, Kojima K, Inokuchi M, Kawano T, Sugihara K. Laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy in patients older than 80. J Surg Res. 2010;161:259–63.

Katai H, Sasako M, Sano T, Fukagawa T. Gastric cancer surgery in the elderly without operative mortality. Surg Oncol. 2004;13:235–8.

Kim MS, Kim S. Outcome of gastric cancer surgery in elderly patients. J Gastric Cancer. 2016;16:254–9.

Schlesinger-Raab A, Mihaljevic AL, Egert S, Emeny R, Jauch KW, Kleeff J, Novotny A, Nussler NC, Rottmann M, Schepp W, et al. Outcome of gastric cancer in the elderly: a population-based evaluation of the Munich cancer registry. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:713–22.

Brenkman HJ, Goense L, Brosens LA et al. A High Lymph Node Yield is Associated with Prolonged Survival in Elderly Patients Undergoing Curative Gastrectomy for Cancer: A Dutch Population-Based Cohort Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:2213–23.

Nashimoto A. Current status of treatment strategy for elderly patients with gastric cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2013;18:969–70.

Rausei S, Ruspi L, Rosa F, Morgagni P, Marrelli D, Cossu A, Cananzi FC, Lomonaco R, Coniglio A, Biondi A, et al. Extended lymphadenectomy in elderly and/or highly co-morbid gastric cancer patients: a retrospective multicenter study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:1881–9.

Ruspi L, Galli F, Pappalardo V, Inversini D, Martignoni F, Boni L, Dionigi G, Rausei S. Lymphadenectomy in elderly/high risk patients: should it be different? Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:5.

Krautz C, Nimptsch U, Weber GF et al. Effect of Hospital Volume on In-hospital Morbidity and Mortality Following Pancreatic Surgery in Germany. Ann Surg. 2018;267:411–7.

Merrill AL, Jha AK, Dimick JB. Clinical effect of surgical volume. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1380–2.

Paoletti X, Oba K, Burzykowski T, Michiels S, Ohashi Y, Pignon JP, Rougier P, Sakamoto J, Sargent D, Sasako M, et al. Benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:1729–37.

Nienhueser H, Kunzmann R, Sisic L, Blank S, Strowitzk MJ, Bruckner T, Jager D, Weichert W, Ulrich A, Buchler MW, et al. Surgery of gastric cancer and esophageal cancer: does age matter? J Surg Oncol. 2015;112:387–95.

Jeong JW, Kwon IG, Son YG, Ryu SW. Could adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery benefit elderly patients with advanced gastric cancer? J Gastric Cancer. 2016;16:260–5.

Hoffman KE, Neville BA, Mamon HJ, Kachnic LA, Katz MS, Earle CC, Punglia RS. Adjuvant therapy for elderly patients with resected gastric adenocarcinoma: population-based practices and treatment effectiveness. Cancer. 2012;118:248–57.

Chang SH, Kim SN, Choi HJ, Park M, Kim RB, Go SI, Lee WS. Adjuvant chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer in elderly and non-elderly patients: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49:263–73.

Strauss J, Hershman DL, Buono D, McBride R, Clark-Garvey S, Woodhouse SA, Abrams JA, Neugut AI. Use of adjuvant 5-fluorouracil and radiation therapy after gastric cancer resection among the elderly and impact on survival. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:1404–12.

Liu KT, Wan JF, Yu GH, Bei YP, Chen X, Lu MZ. The recommended treatment strategy for locally advanced gastric cancer in elderly patients aged 75 years and older: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143:313–20.

Jo JC, Baek JH, Koh SJ, Kim H, Min YJ, Lee BU, Kim BG, Jeong ID, Cho HR, Kim GY. Adjuvant chemotherapy for elderly patients (aged 70 or older) with gastric cancer after a gastrectomy with D2 dissection: a single center experience in Korea. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2015;11:282–7.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WJP and SYH designed the study, and reviewed the manuscript. ZJJ and WXF analyzed the data, and prepared the manuscript. YTS and FM interpreted the data, and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) is a joint project of the Commission on Cancer (CoC) of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. The CoC’s NCDB and the hospitals participating in the CoC NCDB are the source of the de-identified data used herein; they have not verified and are not responsible for the statistical validity of the data analysis or the conclusions derived by the authors. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Comparison of baseline variables between surgery and no surgery group in the elderly patients with resectable proximal GC from NCDB database.

Additional file 2:

Table S2. Treatment strategy of elderly patients with resectable proximal GC from NCDB database.

Additional file 3:

Figure S1. a-b: Postoperative 30-day and 90-day mortality in different age groups of patients with resectable proximal gastric carcinoma (PGC). c-d: Postoperative 30-day and 90-day mortality of elderly patients with resectable PGC treated in different facility.

Additional file 4

: Figure S2. Kaplan-Meier survival curve of elderly patients with resectable proximal gastric carcinoma treated in different facility.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Zhao, J., Fairweather, M. et al. Optimal treatment for elderly patients with resectable proximal gastric carcinoma: a real world study based on National Cancer Database. BMC Cancer 19, 1079 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-6166-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-6166-3