Abstract

Background

There is no consensus regarding the optimal time to initiate adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery for stage III colon cancer, and the relevant postoperative complications that cause delays in adjuvant chemotherapy are unknown.

Methods

Eligible patients aged ≥66 years who were diagnosed with stage III colon cancer from 1992 to 2008 were identified using the linked Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare database. Kaplan-Meier analysis and a Cox proportional hazards model were utilized to evaluate the impact of the timing of adjuvant chemotherapy on overall survival (OS).

Results

A total of 18,491 patients were included. Delayed adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with worse OS (9–12 weeks: hazard ratio [HR] = 1.222, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.063–1.405; 13–16 weeks: HR = 1.252, 95% CI = 1.041–1.505; ≥ 17 weeks: HR = 1.969, 95% CI = 1.663–2.331). The efficacies of adjuvant chemotherapy within 5–8 weeks and ≤4 weeks were similar (HR = 1.045, 95% CI = 0.921–1.185). Compared with the non-chemotherapy group, chemotherapy initiated at ≥21 weeks did not significantly improve OS (HR = 0.882, 95% CI = 0.763–1.018). Patients with postoperative complications, particularly cardiac arrest, ostomy infection, shock, and septicemia, had a significantly higher risk of a 4- to 11-week delay in adjuvant chemotherapy (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Adjuvant chemotherapy initiated within 8 weeks was acceptable for patients with stage III colon cancer. Delayed adjuvant chemotherapy after 8 weeks was significantly associated with worse OS. However, adjuvant chemotherapy might still be useful even with a delay of approximately 5 months. Moreover, postoperative complications were significantly associated with delayed adjuvant chemotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Colon cancer is an important cause of cancer-related incidence and mortality and remains a major public health problem worldwide [1]. The current clinical practice guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommend adjuvant chemotherapy following surgical resection as a standard treatment for patients with stage III colon cancer because of the benefit of chemotherapy in reducing the risk of recurrence and death by eradicating micrometastases [2].

Several studies have reported that the surgical resection of a primary tumor might induce angiogenesis and proliferation of dormant micrometastases by releasing growth-stimulating factors and triggering immunosuppression that leads to tumor growth [3,4,5,6,7]. Moreover, Harless et al. reported that the effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy was inversely proportional to the time from adjuvant chemotherapy initiation to surgical resection [8]. Therefore, it is a reasonable hypothesis that there may be a time-dependent cut-off point after surgery after which the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy is not significant because of the failure to eradicate micrometastases. However, the NCCN and ESMO guidelines do not specify an optimal time to initiate adjuvant chemotherapy after surgical resection. Most clinical trials of adjuvant chemotherapy in colon cancer require adjuvant chemotherapy initiation within 6 to 8 weeks after surgical resection [9,10,11,12]. Routine preclinical and clinical data suggest that adjuvant chemotherapy in colon cancer should be initiated earlier rather than later, but, in real practice, the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy in colon cancer is often delayed [13, 14].

There is no direct and high-quality evidence regarding the importance of the timing of adjuvant chemotherapy in colon cancer. Although two meta-analyses demonstrated that delays in the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy were detrimental to survival in colorectal cancer [15, 16], these meta-analyses included both rectal and colon cancer, and it was thus not clear whether the conclusions could be applied to the treatment of colon cancer because of the biological differences between colon cancer and rectal cancer. To date, few retrospective studies evaluated the impact of the timing of adjuvant chemotherapy on survival in colon cancer, and the results were inconsistent [17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Moreover, the relevant postoperative complications that cause delays in adjuvant chemotherapy are unknown.

Therefore, this population-based study was conducted to assess the impact of the timing of adjuvant chemotherapy on survival in stage III colon cancer and to assess whether postoperative complications were associated with the timing of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Methods

Data source

This study was conducted utilizing the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program and Medicare-linked databases. The SEER program is a comprehensive source of population-based data on patient demographics, tumor characteristics, cancer-related treatments, and causes of death that covers approximately 28% of the population of the United States [24]. The Medicare database contains individual health insurance claims for approximately 97% of the population aged ≥65 years in the United States and complements the SEER with diagnoses, cancer-related treatments, and outcomes. In the Medicare database, Part A provides health-insurance data about hospitals, skilled-nursing facilities, hospices, and home health care, and Part B provides data about physician and outpatient services [25, 26]. The SEER-Medicare database was described in our previous study [27].

The access to the SEER-Medicare database was approved by National Cancer Institute and Information Management Services, Inc. (D6-MEDIC-821), and this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the First Hospital of China Medical University.

Study population

This study included eligible patients aged ≥66 years from SEER-Medicare database who were diagnosed with primary colon adenocarcinoma from 1992 to 2008 (SEER cancer site codes 18.0, and 18.2 to 18.9). The participating patients fulfilled the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging criteria for stage III colon cancer and underwent primary tumor resection with curative intent within 180 days of diagnosis. The adjuvant chemotherapy regimens were 5-fluorourcil (5-FU)/capecitabine alone or 5-FU/capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (FOLFOX/CapeOX). The non-chemotherapy group included patients with no record of chemotherapy within one year of surgery. The FOLFOX/CapeOX group included patients with any record of 5-FU/capecitabine plus oxaliplatin within 4 weeks of their first chemotherapy dose.

The exclusion criteria were the following: (1) patients who previous non-colon cancer or a diagnosis of non-colon cancer within 1 year of the colon cancer diagnosis, (2) those with incomplete pathological stage entries or diagnostic data, (3) those who received adjuvant chemotherapy only after tumor relapse or metastasis, (4) those who received preoperative neoadjuvant treatments or other adjuvant chemotherapy regimens, (5) those who died within 30 days of diagnosis, and (6) those lacked full coverage from Medicare Parts A and B from 12 months before diagnosis to 9 months after diagnosis or were enrolled in a health maintenance organization.

The National Drug Codes for the drugs and the Health Care Financing Administration Common Procedure Coding System have been previously reported [27].

Study variables

We obtained the patient demographics from the SEER patient entitlement and diagnosis summary file, including gender, age at diagnosis, race, marital status, residence location, household income, education level, and year of diagnosis. The disease characteristics, including primary tumor site (right-side or left-side colon), histologic grade (well differentiated, moderately differentiated, or poorly differentiated/undifferentiated), histologic type (adenocarcinoma, mucinous carcinoma, or signet-ring cell carcinoma), tumor stage, presence of preoperative obstruction or perforation, and number of examined lymph nodes (≥12 or < 12) were also studied. The tumor stage was assessed based on the seventh edition of the AJCC TNM staging system [28, 29]. The time to the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy was defined as the interval between the curative surgery and the administration of the first chemotherapy.

For the evaluation of the comorbidities, we used the Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) risk score to summarize the health care problems and predict the future health care cost of the population compared with the average Medicare beneficiary (HCC = 1.0), and the HCC risk score was derived from the Medicare inpatient and outpatient claims for various comorbidities within 12 months before the colon cancer diagnosis [30]. The postoperative complications were identified by assessing the discharge diagnoses within 1 month of surgery.

Statistical analysis

For the descriptive analysis, the categorical variables were compared using χ2 tests and the continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U tests. In the univariate analysis of survival, Kaplan–Meier survival curves for overall survival (OS) were generated according to the chemotherapy regimen and timing of adjuvant chemotherapy, and these curves were compared using log-rank tests. A spline-based hazard ratio (HR) curve with the corresponding confidence limits was used to evaluate the effect of the continuous covariate of interest (i.e., the timing of adjuvant chemotherapy) on the outcome (OS) [31, 32]. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to determine the relationships of multiple survival-related variables with survival.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), STATA version 12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA), SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS, Inc., Somers, NY, USA), and R version 3.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). For all analyses, a two-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

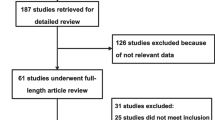

A total of 18,491 patients with stage III colon cancer who underwent surgical resection between 1992 and 2008 were identified using the SEER-Medicare database. Among these, 8058 patients received 5-FU or capecitabine alone, 1664 patients received FOLFOX, and 8769 patients did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. With respect to the timing of adjuvant chemotherapy, 746 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy within 4 weeks after surgery, 6165 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy within 5–8 weeks after surgery, 1883 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy within 9–12 weeks after surgery, 466 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy within 13–16 weeks after surgery, and 462 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy ≥17 weeks after surgery. The patient profiles and disease characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Overall comparison of the timing of chemotherapy

We used a spline-based HR curve to explore the impact of the timing of adjuvant chemotherapy on overall survival in patients with stage III colon cancer. The results indicated that a minimum risk of mortality was achieved at 4 weeks after surgery, and the survival benefits decreased with a delay in the timing of adjuvant chemotherapy of more than 4 weeks (Fig. 1). Therefore, we used the value of ≤4 weeks as a reference for the survival analysis, and the results of univariate analyses indicated that delayed chemotherapy was significantly associated with worse OS (9–12 weeks: HR = 1.169, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.019–1.341, p = 0.026; 13–16 weeks: HR = 1.237, 95% CI = 1.031–1.483, p = 0.022; ≥ 17 weeks: HR = 2.207, 95% CI = 1.870–2.604, p < 0.001). However, chemotherapy that was initiated within 5–8 weeks after surgery did not significantly increase the risk of mortality (HR = 0.982, 95% CI = 0.867–1.113, p = 0.780). A Kaplan–Meier survival curve that was stratified by the timing of chemotherapy is presented in Fig. 2. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models produced results similar to those of the univariate analyses (5–8 weeks: HR = 1.045, 95% CI = 0.921–1.185, p = 0.498; 9–12 weeks: HR = 1.222, 95% CI = 1.063–1.405, p = 0.005; 13–16 weeks: HR = 1.252, 95% CI = 1.041–1.505, p = 0.017; ≥ 17 weeks: HR = 1.969, 95% CI = 1.663–2.331, p < 0.001, Table 2). Moreover, the survival benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy was statistically insignificant when adjuvant chemotherapy was initiated ≥21 weeks after resection compared with the non-chemotherapy group (HR = 0.882, 95% CI = 0.763–1.018, p = 0.087, Fig. 3), and chemotherapy initiated ≥25 weeks after surgery did not elicit an OS benefit compared with the non-chemotherapy group (HR = 1.019, 95% CI = 0.863–1.204, p = 0.821, Fig. 3).

Comparison of the timing of FOLFOX/CapeOX chemotherapy

Our results indicated that the survival benefit from FOLFOX/CapeOX chemotherapy was more evident than that from 5-FU alone in patients with stage III colon cancer (HR = 0.615, 95% CI = 0.555–0.683, p < 0.001, Fig. 4), although both chemotherapy regimens significantly improved the OS (p < 0.001) compared with the non-chemotherapy group. Therefore, the relationship between the timing of FOLFOX/CapeOX chemotherapy and OS was further evaluated. The results of the multivariate analysis indicated that FOLFOX/CapeOX chemotherapy that was initiated within 5–8 weeks did not increase the risk of mortality compared with FOLFOX/CapeOX chemotherapy that was initiated ≤4 weeks after surgery (HR = 1.009, 95% CI = 0.619–1.644, p = 0.971, Table 3). However, FOLFOX/CapeOX chemotherapy initiated within 9–12, 13–16, and ≥17 weeks tended to produce worse OS (9–12 weeks: HR = 1.640, 95% CI = 0.990–2.717, p = 0.055; 13–16 weeks: HR = 1.422, 95% CI = 0.788–2.566, p = 0.243; ≥ 17 weeks: HR = 2.482, 95% CI = 1.354–4.549, p = 0.003, Table 3). Indeed, the spline-based HR curve for FOLFOX/CapeOX chemotherapy indicated that the survival benefit of FOLFOX/CapeOX chemotherapy was not statistically significant when it was initiated at ≥19 weeks compared with the non-chemotherapy group (HR = 0.672, 95% CI = 0.441–1.024, p = 0.064, Fig. 5).

Postoperative complications and the timing of chemotherapy

We examined the correlation of postoperative complications with the delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy. The results indicated that patients with postoperative complications had a significantly higher risk of delayed adjuvant chemotherapy (p < 0.05; Fig. 6). Among the postoperative complications, cardiac arrest (19.50 vs. 8.22 weeks; Δ = 11.28 weeks), ostomy infection (14.60 vs. 8.22 weeks; Δ = 6.38 weeks), shock (13.69 vs. 8.18 weeks; Δ = 5.51 weeks), and septicemia (12.02 vs. 8.13 weeks; Δ = 3.89 weeks) had strong influences on chemotherapy delay with a delay of approximately 4–11 weeks. Additionally, disruption of the operation wound (Δ = 3.11 weeks), peritonitis (Δ = 3.07 weeks), fistula of the gastrointestinal tract (Δ = 2.97 weeks), acute renal failure (Δ = 3.34 weeks), postoperative infection (Δ = 2.85 weeks), intestinal perforation (Δ = 2.02 weeks), acute myocardial infarction (Δ = 1.88 weeks), and stroke (Δ = 1.96 weeks) could result in delays in the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy of approximately 2–3 weeks. In turn, hemorrhage, pneumonia, urinary infection, pulmonary embolism, respiratory disease, gastrointestinal disorder, anemia, vein disease, gastrointestinal disease, nausea and vomiting, and obstruction had relatively weak impacts on the chemotherapy delay (a delay of approximately 0.5–1.5 weeks), although the differences were significant.

Association between postoperative complications and timing of adjuvant chemotherapy (AC) after surgical resection. Orange color bars present the timing of AC among patients with postoperative complications. Blue color bars present the timing of AC among patients without postoperative complications. “**” present a significant difference with p value < 0.01

Discussion

There is no evidence about the optimal time to initiate adjuvant chemotherapy after surgical resection, or whether there is an ideal timing for adjuvant therapy after which treatment benefit decreases. This population-based study based on the SEER-Medicare databases was conducted to evaluate the relationship between the timing of adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in stage III colon cancer. The results indicated that adjuvant chemotherapy that was initiated within 5–8 weeks after surgery did not increase the risk of mortality compared with chemotherapy initiated at ≤4 weeks after surgery, and the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy within 8 weeks after surgery was thus feasible. However, adjuvant chemotherapy after 8 weeks of surgery was significantly associated with worse OS. The survival benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy became statistically insignificant when chemotherapy was initiated after 21 weeks compared with the non-chemotherapy group, thus, adjuvant chemotherapy might be still useful even with a delay of approximately 5 months (Fig. 3). Our results indicated that the survival benefits of the FOLFOX/CapeOX chemotherapy regimen within 5–8 weeks and ≤4 weeks were similar, and chemotherapy initiated ≥19 weeks did not have a significant OS benefit compared with the non-chemotherapy group.

The favorable effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on survival primarily involves the eradication of residual disease and micrometastases. However, the relationship between the timing of adjuvant chemotherapy and survival is unclear. Several studies reported that primary tumor removal could accelerate angiogenesis and growth of residual disease and micrometastases by releasing growth-stimulating factors and promoting immunosuppression [3,4,5,6,7]; thus, a delay in adjuvant chemotherapy might favor tumor angiogenesis and growth, and a long delay could lead to tumor recurrence or metastasis and a consequent failure to achieve the curative potential of adjuvant chemotherapy. Furthermore, Goldie et al. suggested that the drug sensitivity of a tumor was related to the spontaneous mutation rate toward phenotypic drug resistance, which was a function of time [33]. Moreover, the mathematical model by Harless et al. demonstrated that the effectiveness of chemotherapy was inversely proportional to the tumor burden that had to be eradicated, which, in turn, was a function of the time of the initiation of chemotherapy after surgery [8]. Therefore, the survival benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy was time-dependent. Studies have also reported that delayed chemotherapy might reflect poor patient and disease characteristics and increase comorbidity, which would be associated with poor prognoses [13, 34].

Our spline-based HR model revealed that the efficacies of adjuvant chemotherapy within 5–8 weeks and ≤4 weeks were similar, although the minimum risk of mortality was achieved at 4 weeks after surgery. Bos et al. demonstrated that adjuvant chemotherapy within 5–6 weeks or 7–8 weeks after surgery did not decrease OS compared to the initiation of chemotherapy within 4 weeks, and the start of chemotherapy 8 weeks after surgery was associated with a decreased OS [35]. In clinical practice, it is important to note that the toxicity of chemotherapy may be maximized due to poor immune and performance statuses after surgery, and thus, initiating chemotherapy early may cause severe chemotherapy-related adverse events and even death [36]. Therefore, an additional survival benefit of excess-early adjuvant chemotherapy may be difficult to detect because of the severe adverse events caused by chemotherapy. The initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy within 8 weeks after surgery was feasible. However, adjuvant chemotherapy that was initiated ≥21 weeks after surgery did not have a significant survival OS benefit compared with the non-chemotherapy group, and conversely, this delay may cause additional chemotherapy-related adverse events. Further studies are needed to explore the optimal timing for adjuvant chemotherapy, for example, identifying the time at which the survival benefit from chemotherapy maximally outweighs the risks of chemotherapy-related adverse events and death.

Several studies reported that patient and disease characteristics, including older age, low income, and high comorbidity, were associated with delayed adjuvant chemotherapy [13, 34]. Cheung et al. reported that the determinants of delayed adjuvant chemotherapy might be primarily influenced by their relationships with the postoperative complications that ultimately resulted in chemotherapy delay, and these complications seemed to be a more important driver for chemotherapy delay [37]. Therefore, the relationship between postoperative complications and delayed adjuvant chemotherapy was evaluated, and the results indicated that patients with postoperative complications had a significantly higher risk of delayed adjuvant chemotherapy (p < 0.05). Specifically, cardiac arrest, ostomy infection, shock, and septicemia had strong influences on delayed chemotherapy and caused delays of 4–11 weeks. Moreover, disruption of the operation wound, peritonitis, fistula of the gastrointestinal tract, acute renal failure, postoperative infection, intestinal perforation, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke could cause delays of 2–3 weeks. These results were expected because patients with severe postoperative complications were likely to require more time for recovery. Therefore, multidisciplinary treatment strategies are needed to reduce postoperative complications and promote timely adjuvant chemotherapy.

This study has limitations. First, this was a retrospective SEER-Medicare study, and thus the potential for confounding based on patient selection could not be completely eliminated. Second, the data on the patient/disease characteristics and treatments were obtained from a fee-for-service insurance database. Some clinical variables were not available, and the presence of other important confounding factors could not be discarded. Third, the use of adjuvant chemotherapy may decrease in older patients mainly because older patients are more likely to have high comorbidity and poor performance statuses, and oncologists may be less willing to use adjuvant chemotherapy [38, 39]. In our study, the results demonstrated that the use of adjuvant chemotherapy was common in older patients with stage III colon cancer (9722/18,491, 52.6%), and adjuvant chemotherapy significantly improved the prognoses compared with the non-chemotherapy group. Additionally, several studies have also demonstrated that older patients with stage III colon cancer gain a significant survival benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy [40,41,42,43]. Therefore, further large-scale, high-quality studies are needed to evaluate the interactions of age and the timing of adjuvant chemotherapy with survival in stage III colon cancer. Fourth, disease-free survival was also an appropriate measure for assessing the survival benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy; however, disease-free survival could not be evaluated because the data on disease-free survival was not available in the SEER-Medicare database. Further studies are required to investigate the impact of the timing of adjuvant chemotherapy on disease-free survival. Moreover, it was not feasible to conduct a randomized controlled trial to specifically address the impact of the timing of adjuvant chemotherapy on survival in colon cancer. Thus, larger-scale and well-designed retrospective studies are needed to explore the optimal timing of adjuvant chemotherapy after surgical resection.

Conclusions

The survival benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy within 5–8 weeks and ≤4 weeks were similar, and thus, initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy within 8 weeks in patients with stage III colon cancer was feasible. Adjuvant chemotherapy 8 weeks after surgical resection was significantly associated with worse OS. However, adjuvant chemotherapy might still be useful even with a delay of approximately 5 months, although the survival benefit was reduced. Additionally, postoperative complications were significantly associated with the delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with stage III colon cancer.

Abbreviations

- 5-FU:

-

5-fluorourcil

- AJCC:

-

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- CIs:

-

Confidence intervals

- ESMO:

-

The European Society for Medical Oncology

- HCC:

-

Hierarchical Condition Category.

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio.

- NCCN:

-

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

- OS:

-

Overall survival.

- SEER:

-

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

References

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108.

Gill S, Loprinzi CL, Sargent DJ, Thome SD, Alberts SR, Haller DG, Benedetti J, Francini G, Shepherd LE, Francois Seitz J, et al. Pooled analysis of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy for stage II and III colon cancer: who benefits and by how much? Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(10):1797–806.

Hensler T, Hecker H, Heeg K, Heidecke CD, Bartels H, Barthlen W, Wagner H, Siewert JR, Holzmann B. Distinct mechanisms of immunosuppression as a consequence of major surgery. Infect Immun. 1997;65(6):2283–91.

Baum M, Demicheli R, Hrushesky W, Retsky M. Does surgery unfavourably perturb the "natural history" of early breast cancer by accelerating the appearance of distant metastases? European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2005;41(4):508–15.

Fisher B, Gunduz N, Coyle J, Rudock C, Saffer E. Presence of a growth-stimulating factor in serum following primary tumor removal in mice. Cancer Res. 1989;49(8):1996–2001.

Gunduz N, Fisher B, Saffer EA. Effect of surgical removal on the growth and kinetics of residual tumor. Cancer Res. 1979;39(10):3861–5.

Stalder M, Birsan T, Hausen B, Borie DC, Morris RE. Immunosuppressive effects of surgery assessed by flow cytometry in nonhuman primates after nephrectomy. Transplant international : official journal of the European Society for Organ Transplantation. 2005;18(10):1158–65.

Harless W, Qiu Y. Cancer: a medical emergency. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67(5):1054–9.

Andre T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, Navarro M, Tabernero J, Hickish T, Topham C, Zaninelli M, Clingan P, Bridgewater J, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(23):2343–51.

Andre T, Boni C, Navarro M, Tabernero J, Hickish T, Topham C, Bonetti A, Clingan P, Bridgewater J, Rivera F, et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(19):3109–16.

Van Cutsem E, Labianca R, Bodoky G, Barone C, Aranda E, Nordlinger B, Topham C, Tabernero J, Andre T, Sobrero AF, et al. Randomized phase III trial comparing biweekly infusional fluorouracil/leucovorin alone or with irinotecan in the adjuvant treatment of stage III colon cancer: PETACC-3. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(19):3117–25.

Wolmark N, Bryant J, Smith R, Grem J, Allegra C, Hyams D, Atkins J, Dimitrov N, Oishi R, Prager D, et al. Adjuvant 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin with or without interferon alfa-2a in colon carcinoma: National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and bowel project protocol C-05. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(23):1810–6.

Xu F, Rimm AA, Fu P, Krishnamurthi SS, Cooper GS. The impact of delayed chemotherapy on its completion and survival outcomes in stage II colon cancer patients. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107993.

Chan A, Woods R, Kennecke H, Gill S. Factors associated with delayed time to adjuvant chemotherapy in stage iii colon cancer. Current oncology (Toronto, Ont). 2014;21(4):181–6.

Des Guetz G, Nicolas P, Perret GY, Morere JF, Uzzan B. Does delaying adjuvant chemotherapy after curative surgery for colorectal cancer impair survival? A meta-analysis. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2010;46(6):1049–55.

Biagi JJ, Raphael MJ, Mackillop WJ, Kong W, King WD, Booth CM. Association between time to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305(22):2335–42.

Bayraktar UD, Chen E, Bayraktar S, Sands LR, Marchetti F, Montero AJ, Rocha-Lima CM. Does delay of adjuvant chemotherapy impact survival in patients with resected stage II and III colon adenocarcinoma? Cancer. 2011;117(11):2364–70.

Haynes A, Chiang Y, Feig B, Xing Y, Chang G, You Y, Cormier J. Association between delays in adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer and increased mortality. J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts). 2012;30(4_suppl):541.

Czaykowski PM, Gill S, Kennecke HF, Gordon VL, Turner D. Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer: does timing matter? Dis colon rectum. 2011;54(9):1082–9.

Yu S, Shabihkhani M, Yang D, Thara E, Senagore A, Lenz HJ, Sadeghi S, Barzi A. Timeliness of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III adenocarcinoma of the colon: a measure of quality of care. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2013;12(4):275–9.

Peixoto RD, Kumar A, Speers C, Renouf D, Kennecke HF, Lim HJ, Cheung WY, Melosky B, Gill S. Effect of delay in adjuvant oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2015;14(1):25–30.

Zeig-Owens R, Gershman ST, Knowlton R, Jacobson JS. Survival and time interval from surgery to start of chemotherapy among colon cancer patients. J Registry Manag. 2009;36(2):30–41. quiz 61-32

Berglund A, Cedermark B, Glimelius B. Is it deleterious to delay the start of adjuvant chemotherapy in colon cancer stage III? Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2008;19(2):400–2.

National Cancer Institute: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. [https://seer.cancer.gov/index.html].

Potosky AL, Riley GF, Lubitz JD, Mentnech RM, Kessler LG. Potential for cancer related health services research using a linked Medicare-tumor registry database. Med Care. 1993;31(8):732–48.

SEER-Medicare Linked Database. [https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/seermedicare/].

Gao P, Song YX, Sun JX, Chen XW, Xu YY, Zhao JH, Huang XZ, Xu HM, Wang ZN. Which is the best postoperative chemotherapy regimen in patients with rectal cancer after neoadjuvant therapy? BMC Cancer. 2014;14:888.

Edge SBBD, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010.

Sobin LHGM, Wittekind C. UICC: TNM classification of malignant tumours. 7th ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009.

Ash AS, Ellis RP, Pope GC, Ayanian JZ, Bates DW, Burstin H, Iezzoni LI, MacKay E, Yu W. Using diagnoses to describe populations and predict costs. Health care financing review. 2000;21(3):7–28.

Meira-Machado L, Cadarso-Suarez C, Gude F, Araujo A. smoothHR: an R package for pointwise nonparametric estimation of hazard ratio curves of continuous predictors. Computational and mathematical methods in medicine. 2013;2013:745742.

Zhang Z. Semi-parametric regression model for survival data: graphical visualization with R. Annals of translational medicine. 2016;4(23):461.

Goldie JH, Coldman AJ. A mathematic model for relating the drug sensitivity of tumors to their spontaneous mutation rate. Cancer treatment reports. 1979;63(11–12):1727–33.

Hershman D, Hall MJ, Wang X, Jacobson JS, McBride R, Grann VR, Neugut AI. Timing of adjuvant chemotherapy initiation after surgery for stage III colon cancer. Cancer. 2006;107(11):2581–8.

Bos AC, van Erning FN, van Gestel YR, Creemers GJ, Punt CJ, van Oijen MG, Lemmens VE. Timing of adjuvant chemotherapy and its relation to survival among patients with stage III colon cancer. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2015;51(17):2553–61.

Goldman LI, Lowe S, al-Saleem T: Effect of fluorouracil on intestinal anastomoses in the rat. Arch Surg.(Chicago, Ill : 1960) 1969, 98(3):303–304.

Cheung WY, Neville BA, Earle CC. Etiology of delays in the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy and their impact on outcomes for stage II and III rectal cancer. Dis colon rectum. 2009;52(6):1054–1063; discussion 1064.

van Erning FN, Creemers GJ, De Hingh IH, Loosveld OJ, Goey SH, Lemmens VE. Reduced risk of distant recurrence after adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with stage III colon cancer aged 75 years or older. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2013;24(11):2839–44.

van den Broek CBM, Puylaert C, Breugom AJ, Bastiaannet E, de Craen AJM, van de Velde CJH, Liefers GJ, Portielje JEA. Administration of adjuvant chemotherapy in older patients with stage III colon cancer: an observational study. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2017;19(10):O358–64.

Sanoff HK, Carpenter WR, Sturmer T, Goldberg RM, Martin CF, Fine JP, McCleary NJ, Meyerhardt JA, Niland J, Kahn KL, et al. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on survival of patients with stage III colon cancer diagnosed after age 75 years. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(21):2624–34.

van Steenbergen LN, Lemmens VE, Rutten HJ, Wymenga AN, Nortier JW, Janssen-Heijnen ML. Increased adjuvant treatment and improved survival in elderly stage III colon cancer patients in The Netherlands. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2012;23(11):2805–11.

Kim KY, Cha IH, Ahn JB, Kim NK, Rha SY, Chung HC, Roh JK, Shin SJ. Estimating the adjuvant chemotherapy effect in elderly stage II and III colon cancer patients in an observational study. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107(6):613–8.

van Erning FN, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Creemers GJ, Pruijt JF, Maas HA, Lemmens VE. Recurrence-free and overall survival among elderly stage III colon cancer patients treated with CAPOX or capecitabine monotherapy. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2017;140(1):224–33.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Clinical Capability Construction Project for Liaoning Provincial Hospitals (LNCCC-A01-2014), Program of Education Department of Liaoning Province (L2014307), and the National Key R&D Program of China (MOST-2016YFC1303200, MOST-2016YFC1303202). The authors thank the department of Surgical Oncology of First Hospital of China Medical University for technical assistance. The corresponding author had full access to all the data and analyses.

Funding

This work was funded by Clinical Capability Construction Project for Liaoning Provincial Hospitals (LNCCC-A01–2014), Program of Education Department of Liaoning Province (L2014307), and the National Key R&D Program of China (MOST-2016YFC1303200, MOST-2016YFC1303202). The sponsors had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from SEER-Medicare database but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of SEER-Medicare database.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PG: Design of the work, data acquisition, data analysis, data interpretation, writing-original draft, and writing-review and editing. XZH: Design of the work, data acquisition, data interpretation, writing-original draft, and writing-review and editing. YXS: Data acquisition, data analysis, data interpretation, writing-original draft, and writing-review and editing. JXS: Data acquisition, data analysis, data interpretation, writing-original draft, and writing-review and editing. XWC: Data acquisition, data interpretation, writing-original draft, and writing-review and editing. YS: Data acquisition, data interpretation, writing-original draft, and writing-review and editing. YMJ: Data acquisition, data interpretation, writing-original draft, and writing-review and editing. ZNW: Responsible for conception and design of the work, data acquisition, data analysis, data interpretation, writing-original draft, and writing-review and editing. All authors read and approve the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Because the SEER-Medicare data are de-identified and are based on registry data, no prior informed consent was required. The access to the SEER-Medicare database was approved by the National Cancer Institute and Information Management Services, Inc. (D6-MEDIC-821), while this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the First Hospital of China Medical University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, P., Huang, Xz., Song, Yx. et al. Impact of timing of adjuvant chemotherapy on survival in stage III colon cancer: a population-based study. BMC Cancer 18, 234 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4138-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4138-7