Abstract

Background

Sorafenib and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) are recommended therapies for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), but their combined efficacy remains unclear.

Methods

Between August 2004 and November 2014, 104 patients with BCLC stage B/C HCC were enrolled at the Affiliated Tumor Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, China. Forty-eight patients were treated with sorafenib alone (sorafenib group) and 56 with TACE plus sorafenib (TACE + sorafenib group). Baseline demographic/clinical data were collected. The primary outcomes were median overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). Secondary outcomes were overall response rate (ORR) and sorafenib-related adverse events (AEs). Baseline characteristics associated with disease prognosis were identified using multivariate Cox hazards regression.

Results

The mean age of the 104 patients (94 males; 90.38%) was 49.02 ± 12.29 years. Of the baseline data, only albumin level (P = 0.028) and Child-Pugh class (P = 0.017) differed significantly between groups. Median OS did not differ significantly between the sorafenib and TACE + sorafenib groups (18.0 vs. 22.0 months, P = 0.223). Median PFS was significantly shorter in the sorafenib group than that in the TACE + sorafenib group (6.0 vs. 8.0 months, P = 0.004). Six months after treatments, the ORRs were similar between the sorafenib and TACE + sorafenib groups (12.50% vs. 18.75%, P = 0.425). The rates of grade III–IV adverse events in sorafenib and TACE + sorafenib groups were 29.2% vs. 23.2%, respectively. TACE plus sorafenib treatment (HR = 0.498, 95% CI = 0.278–0.892), no vascular invasion (HR = 0.354, 95% CI = 0.183–0.685) and Child-Pugh class A (HR = 0.308, 95% CI = 0.141–0.674) were significantly associated with better OS, while a larger tumor number was predictive of poorer OS (HR = 1.286, 95% CI = 1.031–1.604). TACE plus sorafenib treatment (HR = 0.461, 95% CI = 0.273–0.780) and no vascular invasion (HR = 0.557, 95% CI = 0.314–0.988) were significantly associated with better PFS.

Conclusions

Compared with sorafenib alone, combining TACE with sorafenib might prolong survival and delay disease progression in patients with advanced HCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer in the world [1], and a variety of treatments are available [2,3,4]. Surgery is a potentially curative therapy for HCC [5], but many patients are not eligible for surgery because they are diagnosed with HCC at a very late stage [6, 7]. According to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) Group, patients with BCLC stage B/C HCC are not suitable for surgery [5]. Suitable alternative treatments for patients with BCLC stage B and C HCC are transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and sorafenib, respectively.

TACE is widely used as a palliative treatment for patients with advanced HCC and has been reported to prolong survival [8, 9]. TACE consists of two procedures: embolization of the tumor-feeding artery to cause tumor necrosis, and local delivery of antitumor drugs to the tumor-feeding artery to enhance tumor necrosis [10]. Previously, we found that embolization is the most important part of the TACE procedure [11, 12], with tumor necrosis initiated after the feeding blood supply has been shut down. Some studies [13, 14] have observed that the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) level increases after TACE, suggesting that a pharmacologic intervention that impairs VEGF signaling and thus the development of new blood vessels could be a clinically useful adjuvant therapy for TACE.

Sorafenib is a small-molecule inhibitor of several tyrosine protein kinases that are thought to play an important role in tumor progression, including platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-β, Raf serine/threonine kinases and VEGF receptors (VEGFRs) [15, 16]. Since sorafenib suppresses VEGF signaling by inhibiting VEGFRs, it would be expected to enhance the efficacy of TACE by inhibiting angiogenesis and thereby promoting tumor apoptosis [17].

Patients with portal vein tumor thrombus (PVTT) are defined as BCLC stage C and are recommended to receive sorafenib therapy, while TACE is the recommended therapy for patients with BCLC stage B HCC. Several studies have suggested that the combination of TACE with sorafenib can provide a survival benefit in patients with PVTT, as compared with TACE mono-therapy [18,19,20]. However, whether the addition of TACE would enhance the efficacy of sorafenib therapy in these patients remains controversial.

In the present study, we compared efficacy and safety between sorafenib mono-therapy and TACE combined with sorafenib in patients with BCLC stage B/C HCC. In addition, multivariate regression analysis was used to identify clinical factors predicting overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), and further analyses were undertaken to determine whether tumor size influenced OS and PFS.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Guangxi Medical University and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and internationally accepted ethical guidelines. During their admission for surgery, the patients enrolled in this study provided written informed consent for their information to be stored in hospital databases and used for research. During data collection, patient records were anonymized. Patient admission and consent procedures have been described previously [21].

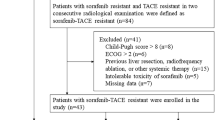

Patient enrollment

This retrospective study included 104 patients with HCC between August 2004 and November 2014. Patients treated with TACE and sorafenib were included in the TACE + sorafenib group (n = 56); patients who were treated only with sorafenib were included in the sorafenib group (n = 48). All patients were diagnosed with HCC based on the criteria of the European Association for the Study of the Liver [22].

The inclusion criteria were: (a) 18–75 years old; (b) HCC classified as either unresectable BCLC stage B or BCLC stage C [23]; and(c) liver function classified as Child-Pugh class A or B.

Patients were excluded from the study if they had any of the following: (a) malignant tumors of other organ systems; (b) HCC of Child-Pugh class C; or (c) any contraindication for therapy with TACE (e.g., complete obstruction of the portal vein) or sorafenib (e.g., allergy to sorafenib).

Collection of baseline data

The following information was obtained for all patients included in the analysis: disease history; physical examination findings; results of serum laboratory tests (total bilirubin, TBil; albumin, ALB; alanine aminotransferase, ALT; platelet count, PLT; prothrombin time, PT; α-fetoprotein level, AFP; and hepatitis B virus surface antigen, HBsAg); and results of radiologic investigations (computed tomography, CT; magnetic resonance imaging, MRI; and/or Doppler ultrasound).

PVTT was confirmed by radiologic investigations (a filling defect sign in CT or MRI images; or ultrasonographic features of a mass in the portal vein). PVTT type was defined according to a previous study [24] as follows: type I, tumor thrombus (TT) involving segmental branches of the portal vein or above; type II, TT involving the right/left portal vein; type III, TT involving the main portal vein trunk; or type IV, TT involving the superior mesenteric vein or inferior vena cava.

Portal vein hypertension (PVH) was defined as the presence of esophageal varices and/or a platelet count <100,000 /μL in association with splenomegaly.

Transarterial chemoembolization

We used the Seldinger technique [25] and introduced a 4.1-French RC1 catheter into the tumor feeding artery. Afterwards, we carefully identified the number, location, size and branches of the tumor. A mixture of 10–20 mL iodized oil, gelfoam particles with 30–50 mg doxorubicin and 50–100 mg cisplatinum were injected into the arterial branches. The number of TACE cycles administered ranged from 1 to 6, with TACE repeated at 1-month intervals, depending on the patients’ liver function and tumor shrinkage.

Sorafenib

Sorafenib was administered orally from the beginning of the treatment period (i.e. treatment was initiated before TACE was performed in those receiving combination therapy) at a dosage of 400 mg twice daily (Bayer HealthCare AG, 200 mg/pill). The sorafenib dose was adjusted if adverse drug events (ADEs) developed. If grade I or 2 ADEs (National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0; [26]) occurred, we adopted a wait-and-see policy. Usually these ADEs disappeared spontaneously, but if they persisted the drug was either reduced in dosage or discontinued. When grade 3 or 4 ADEs occurred, the oral dose was reduced to 200 mg per day. If the ADEs had not disappeared or decreased in severity 1 week after dose adjustment, it was recommended that the patient stop receiving sorafenib until the symptoms had alleviated or disappeared. In patients receiving combination therapy, treatment with sorafenib was continued during and after the performance of TACE.

Post-therapy evaluation and follow-up

Patients were asked to return to the hospital for follow-up every 1–2 months after discharge. During each follow-up, blood tests and radiologic investigations were performed as at baseline. Tumor response was recorded during every follow-up and classified (based on the best response) after 6 months, according to the Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors for HCC (mRECIST) [27, 28], as either complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD) or progressive disease (PD). Patients lost to follow-up were excluded from the final analysis.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures in our study were OS and PFS.PFS was defined as the duration from patient discharge to disease progression (according to mRECIST guideline). Secondary outcome measures were tumor response and the occurrence of ADEs.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 18.0 (IBM, Chicago, USA) was used for statistical analysis. A P value <0.05 was defined as the threshold of statistical significance. Normally distributed data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), non-normally distributed data are expressed as median (range), and enumeration data are expressed as n (%). Differences in outcomes between the two therapy groups were assessed for significance using independent-samples t-tests or χ2 tests. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to evaluate the effects of patient characteristics on OS and PFS. Factors significantly associated with OS or PFS were identified by multivariate analysis using a stepwise Cox model, with calculation of hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In addition to the type of therapy used (TACE + sorafenib versus sorafenib), the other factors entered into the multivariate analysis were patient age, patient gender (male versus female), tumor number, tumor diameter, vascular invasion (present versus absent), metastasis (present versus absent), Child-Pugh stage (A versus B), and AFP level (< 400 ng/mL versus ≥400 ng/mL). These other parameters were chosen so as to be representative of factors known to be associated with HCC progression or patient survival. Additional variables related to these factors were not included in the multivariate analysis (for example, other parameters related to liver function were excluded as they are related to Child-Pugh stage). A subgroup analysis based on PVTT status was conducted to try and identify whether a subset of patients might benefit more from combination therapy with TACE and sorafenib. An additional analysis was also performed to determine whether tumor size influenced OS and PFS.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

From August 2004 to November 2014, a total of 104 patients with HCC (mean age, 49.02 ± 12.29 years) were included in this retrospective study, including 94 males and 10 females. All patients’ data are attached in the Additional file 1 (organized file). Forty-eight patients received sorafenib mono-therapy while 56 patients received sorafenib plus TACE therapy. The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between the two treatment groups, except that patients in the TACE + sorafenib group had a significantly higher level of ALB (P = 0.028) and proportionally more patients with Child-Pugh class A disease (P = 0.017). There were no therapy-related deaths, and in-hospital mortality was zero (Table 1).

Comparisons of efficacy between TACE/sorafenib combination therapy and sorafenib mono-therapy

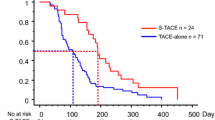

Median OS was 22.0 months (95% CI: 14.1–29.9 months) in the TACE + sorafenib group and 18.0 months (95% CI: 11.8–24.2 months) in the sorafenib group, with no significant difference between groups (P = 0.223; Fig. 1 and Table 2). However, median PFS was significantly longer in the TACE + sorafenib group (8.0 months; 95% CI: 3.4–12.6) than in the sorafenib group (6.0 months; 95% CI: 3.3–8.7 months; P = 0.004; Fig. 1 and Table 2), indicating that combination therapy was more effective than sorafenib mono-therapy at limiting disease progression.

Tumor response

Data for tumor response at 6 months were available for 40 patients in the sorafenib group and 48 patients in the TACE + sorafenib group (Table 3). There were no significant differences between treatment groups in the CR rate (P = 1.000), PR rate (P = 0.502), SD rate (P = 0.574), PD rate (P = 0.906) and OR rate (P = 0.425). Furthermore, subgroup analysis on the basis of the presence (i.e., types I, II, III or IV) or absence of PVTT also showed no statistical differences between the sorafenib and TACE + sorafenib groups in the tumor response 6 months after treatments (all P > 0.05; Table 4). This suggests that the two treatment regimens were similar with regard to reducing tumor size.

Adverse events

There were no significant differences between the sorafenib and TACE + sorafenib groups in the incidences of grade I, II, III and IV ADEs (all P > 0.05), and all ADEs were tolerable. Grade III ADEs occurred in 14 patients in the sorafenib group and 13 patients in the TACE + sorafenib group, while no Grade IV ADEs were observed (Table 5). Symptoms in patients with grade III ADEs disappeared or were alleviated following adjustment of the sorafenib dose or administration of symptomatic supportive treatments. These findings indicate that the addition of TACE to sorafenib therapy does not result in a notable increase in the incidence or severity of ADEs.

Clinical factors influencing OS and PFS

Multivariate Cox regression analysis identified use of TACE + sorafenib combination therapy (HR = 0.498, 95% CI = 0.278–0.892, P = 0.019), no vascular invasion (HR = 0.354, 95% CI = 0.183–0.685, P = 0.002) and Child-Pugh class A (HR = 0.308, 95% CI = 0.141–0.674, P = 0.003) as independent factors predicting better OS, while tumor number (HR = 1.286, 95% CI = 1.031–1.604, P = 0.026) was an independent factor predicting poorer OS (Table 6). Similarly, use of TACE + sorafenib combination therapy (HR = 0.461, 95% CI = 0.273–0.780, P = 0.004) and no vascular invasion (HR = 0.557, 95% CI = 0.314–0.988, P = 0.045) were independent factors predicting a better PFS (Table 7).

Further analyses of OS and PFS based on tumor diameter

The observation that tumor diameter was not an independent predictor of OS and PFS in the multivariate analysis was perhaps unexpected. One possibility we considered was that OS and PFS might only be influenced by tumor size once the tumor exceeded a certain diameter. To explore this possibility, OS and PFS were further analyzed based on different tumor diameters (Table 8 and Fig. 2); the cutoff value of5 cm was based on that used in the TNM classification, while the additional higher cutoff value of 7 cm was arbitrarily chosen. Median OS was 44.0 months (95% CI: 21.624–66.376) in patients with a tumor diameter < 5 cm and 17.0 months (95% CI: 11.806–22.194) in patients with a tumor diameter ≥ 5 cm (P = 0.004; Fig. 2a); in contrast, PFS did not differ between the two groups (8.0 months versus 7.0 months, respectively, P = 0.268; Fig. 2b). Patients with a tumor diameter < 7 cm had a median OS of 38.0 months (95% CI: 20.228–55.772) and a median PFS of 9.0 months (95% CI: 6.003–11.997), while patients with a tumor diameter ≥ 7 cm had a median OS of 14 months (95% CI: 10.409–17.591) and a median PFS of 5.0 months (95% CI: 3.007–6.993); both OS and PFS differed significantly between the two groups (P < 0.05; Fig. 2c and d).

Comparison of survival outcomes between patients with different tumor diameters. a Overall survival (OS, months) in patients with a tumor diameter < 5 cm and those with a tumor diameter ≥ 5 cm. b Progression-free survival (PFS, months)in patients with a tumor diameter < 5 cm and those with a tumor diameter ≥ 5 cm. c Overall survival (OS, months) in patients with a tumor diameter < 7 cm and those with a tumor diameter ≥ 7 cm. d Progression-free survival (PFS, months)in patients with a tumor diameter < 7 cm and those with a tumor diameter ≥ 7 cm

Discussion

The main finding of the present study was that both TACE combined with sorafenib and sorafenib alone were safe and effective treatments for patients with BCLC stage B/C HCC. Although there were no significant differences between treatment groups in OS or tumor response at 6 months, patients treated with TACE/sorafenib combination therapy showed a significantly longer PFS than patients treated with sorafenib alone. Multivariate analysis indicated that TACE/sorafenib combination therapy (versus sorafenib mono-therapy), no vascular invasion and Child-Pugh stage A (versus B) were independent predictors of better OS, while tumor number was a predictor of poorer OS. Furthermore, TACE/sorafenib combination therapy and no vascular invasion were independent predictors of better PFS. Importantly, the addition of TACE to sorafenib therapy was not associated with a significant increase in the occurrence of ADEs. We conclude that, compared with sorafenib alone, TACE plus sorafenib combination therapy in patients with BCLC stage B/C HCC may improve PFS and be associated with improved OS, without a notable increase in adverse events.

Numerous clinical studies have reported that mono-therapy with sorafenib can provide survival benefits over placebo [29,30,31,32,33] or conservative management strategies [34] in patients with advanced HCC. The median OS and PFS in our study (18.0 and 6.0 months, respectively) were longer than those reported in previous studies (6.5–10.7 months and 2.8–5.5 months, respectively) [29,30,31,32,33,34] and may reflect differences between studies in the baseline clinical characteristics of the patients, such as BCLC stage, Child-Pugh stage, vascular invasion and extrahepatic spread.

TACE has also been shown to be an effective treatment option for advanced HCC [8, 9]. There have been a number of investigations comparing the efficacy of TACE plus sorafenib with TACE alone, and most have suggested that combination therapy has superior efficacy to TACE mono-therapy [35,36,37,38,39], although a minority have reported no additional benefit [40]. In our study, the median OS and PFS in patients treated with TACE/sorafenib combination therapy were 22.0 months and 8.0 months, respectively, which are broadly in agreement with values reported previously (12–29 months and 6.3–16.4 months, respectively) [38, 39, 41].

However, fewer studies have compared sorafenib mono-therapy with TACE/sorafenib combination therapy in patients with advanced HCC. Zhang et al. [42] reported that, compared with sorafenib alone, combination therapy resulted in a better OS (15.0 months versus 5.0 months) and PFS (6.0 months versus 2.5 months). Similar results were obtained by Choi et al. [43], who found that the addition of TACE to sorafenib yielded improvements in OS (8.9 months versus 5.9 months) and PFS (2.5 months versus 2.1 months). In agreement with these studies, we also observed a significantly longer PFS in patients treated with combination therapy than in those receiving sorafenib mono-therapy. Although our univariate analysis found no significant difference between groups in OS, the multivariate analysis did identify combination therapy (versus sorafenib alone) as a predictor of longer OS. This apparent inconsistency may have been due to one or more confounding factors (which were accounted for in the multivariate analysis) influencing the results of the direct comparisons of outcome measures between groups. Taken together, these data support the use of TACE/sorafenib combination therapy in patients with advanced HCC.

The most common ADEs noted in our study were hand-foot skin reactions, vomiting and diarrhea, and the majority were grade 1 adverse events, consistent with previous research [39, 44, 45]. Importantly, no serious ADEs were reported in patients with TACE combined with sorafenib, indicating that this therapy is safe. Our observations are in agreement with previous studies reporting that the combination of TACE and sorafenib is not associated with a significantly greater incidence/severity of adverse events than TACE or sorafenib mono-therapy [42, 46].

Our multivariate analysis indicated that Child-Pugh class A, no vascular invasion and lower tumor number were predictors of better OS. In addition, further analysis showed that tumor size ≥7 cm was also associated with poorer OS and PFS. These findings are in agreement with previous investigations that have identified Child-Pugh class, vascular invasion, tumor size, as well as BCLC stage, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status and alanine transaminase, as independent predictors of prognosis [47,48,49]. Although the tumor number and tumor size are both recognized as being associated with prognosis [50], a recent study has suggested that total tumor volume may be a better predictor of outcomes [51].

In our study, the median survival of patients with PVTT treated with sorafenib alone was 9 months, which is longer than that reported previously for patients receiving conservative therapy (3.6–3.8 months) or TACE (7.0–7.3 months) [25, 52]. One study demonstrated that sorafenib mono-therapy had similar efficacy to TACE/sorafenib combination therapy in patients with PVTT [53], while another reported that the addition of sorafenib to TACE improved survival in patients with PVTT [20]. This may indicate that sorafenib therapy may be superior to TACE in the management of patients with advanced HCC and PVTT, and that sorafenib mono-therapy may be sufficient in this subset of patients.

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study, hence selection and reporting bias cannot be excluded. Although the baseline characteristics were similar between the two treatment groups, suggesting that the degree of bias may not have been large, it was notable that the TACE + sorafenib group contained a significantly higher proportion of patients with liver disease classed as Child-Pugh A. This was a retrospective study in which the treatment regimen was usually chosen by the doctor; since TACE is an invasive procedure, it is more likely to have been recommended to patients with better liver function. Although this potential selection bias may have influenced the results of direct comparisons between groups, any potential bias would have been accounted for by the multivariate regression analysis, which found that TACE/sorafenib combination therapy was an independent predictor of both OS and PFS. Second, tumor response was only evaluated at one time point, whereas sequential monitoring over the period of the study would have provided more detailed information regarding the efficacies of the treatment regimens. Third, our sample size was relatively small, so the study may have been underpowered to detect real differences for some comparisons. Fourth, this was a single-center study, so the findings may not be generalizable to other regions of China or other countries. Therefore, multi-center, prospective, randomized, controlled trials are required to confirm and extend our observations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, both TACE combined with sorafenib and sorafenib alone were safe and effective treatments for patients with BCLC stage B/C HCC.TACE/sorafenib combination therapy may have advantages over sorafenib mono-therapy in terms of progression-free survival and possibly OS, without a notable increase in adverse events.

Abbreviations

- AEs:

-

Adverse events

- BCLC:

-

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- CIs:

-

Confidence intervals

- CR:

-

Complete response

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HRs:

-

Hazard ratios

- mRECIST:

-

Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- ORR:

-

Overall response rate

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PD:

-

Progressive disease

- PDGFR:

-

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- PR:

-

Partial response

- PVH:

-

Portal vein hypertension

- PVTT:

-

Portal vein tumor thrombus

- SD:

-

Stable disease

- TACE:

-

Transarterial chemoembolization

- TT:

-

Tumor thrombus

- VEGFRs:

-

VEGF receptors

References

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi:10.3322/caac.21262.

Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362(9399):1907–17. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14964-1.

Llovet JM, Fuster J, Bruix J. Barcelona-clinic liver cancer G. The Barcelona approach: diagnosis, staging, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2004;10(2 Suppl 1):S115–20. doi:10.1002/lt.20034.

Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2012;379(9822):1245–55. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61347-0.

Bruix J, Gores GJ, Mazzaferro V. Hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical frontiers and perspectives. Gut. 2014;63(5):844–55. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306627.

Poon RT, Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, Wong J. Long-term survival and pattern of recurrence after resection of small hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with preserved liver function: implications for a strategy of salvage transplantation. Ann Surg. 2002;235(3):373–82.

Chen MF, Hwang TL, Jeng LB, Wang CS, Jan YY, Chen SC. Postoperative recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Two hundred five consecutive patients who underwent hepatic resection in 15 years. Arch Surg. 1994;129(7):738–42.

Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, Liu CL, Lam CM, Poon RT, et al. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;35(5):1164–71. doi:10.1053/jhep.2002.33156.

Llovet JM, Real MI, Montana X, Planas R, Coll S, Aponte J, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9319):1734–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08649-X.

Bruix J, Llovet JM, Castells A, Montana X, Bru C, Ayuso MC, et al. Transarterial embolization versus symptomatic treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: results of a randomized, controlled trial in a single institution. Hepatology. 1998;27(6):1578–83. doi:10.1002/hep.510270617.

Xie ZB, Ma L, Wang XB, Bai T, Ye JZ, Zhong JH, et al. Transarterial embolization with or without chemotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(9):8451–9. doi:10.1007/s13277-014-2340-z.

Xie ZB, Wang XB, Peng YC, Zhu SL, Ma L, Xiang BD, et al. Systematic review comparing the safety and efficacy of conventional and drug-eluting bead transarterial chemoembolization for inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2015;45(2):190–200. doi:10.1111/hepr.12450.

Bao Y, Feng WM, Tang CW, Zheng YY, Gong HB, Hou EG. Endostatin inhibits angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma after transarterial chemoembolization. Hepato-Gastroenterology. 2012;59(117):1566–8. doi:10.5754/hge12138.

Poon RT, Lau C, Yu WC, Fan ST, Wong J. High serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor predict poor response to transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study. Oncol Rep. 2004;11(5):1077–84.

Jia L, Kiryu S, Watadani T, Akai H, Yamashita H, Akahane M, et al. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus: assessment based on clinical and computer tomography characteristics. Acta Med Okayama. 2012;66(2):131–41.

Wang B, Xu H, Gao ZQ, Ning HF, Sun YQ, Cao GW. Increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Acta Radiol. 2008;49(5):523–9. doi:10.1080/02841850801958890.

Strebel BM, Dufour JF. Combined approach to hepatocellular carcinoma: a new treatment concept for nonresectable disease. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2008;8(11):1743–9. doi:10.1586/14737140.8.11.1743.

Hu H, Duan Z, Long X, Hertzanu Y, Shi H, Liu S, et al. Sorafenib combined with transarterial chemoembolization versus transarterial chemoembolization alone for advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a propensity score matching study. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96620. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096620.

Pan T, Li XS, Xie QK, Wang JP, Li W, Wu PH, et al. Safety and efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal venous tumour thrombus. Clin Radiol. 2014;69(12):e553–61. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2014.09.007.

Zhu K, Chen J, Lai L, Meng X, Zhou B, Huang W, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus: treatment with transarterial chemoembolization combined with sorafenib--a retrospective controlled study. Radiology. 2014;272(1):284–93. doi:10.1148/radiol.14131946.

Zhong JH, Li H, Xiao N, Ye XP, Ke Y, Wang YY, et al. Hepatic resection is safe and effective for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and portal hypertension. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e108755. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0108755.

European Association For The Study Of The L, European Organisation For R, Treatment Of C. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56(4):908–43. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001.

Zhong JH, Ke Y, Gong WF, Xiang BD, Ma L, Ye XP, et al. Hepatic resection associated with good survival for selected patients with intermediate and advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2014;260(2):329–40. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000000236.

Quirk M, Kim YH, Saab S, Lee EW. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein thrombosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(12):3462–71. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i12.3462.

Ye JZ, Zhang YQ, Ye HH, Bai T, Ma L, Xiang BD, et al. Appropriate treatment strategies improve survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with portal vein tumor thrombus. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(45):17141–7. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i45.17141.

National Cancer Institute. Common terminology criteria for adverse events, version 3.0. 2006. http://ctep.cancer.gov/reporting/ctc.html. Accessed 18 June 2009.

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(3):205–16.

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–47. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026.

Bruix J, Raoul JL, Sherman M, Mazzaferro V, Bolondi L, Craxi A, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: subanalyses of a phase III trial. J Hepatol. 2012;57(4):821–9. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2012.06.014.

Cheng AL, Guan Z, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma according to baseline status: subset analyses of the phase III Sorafenib Asia-Pacific trial. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(10):1452–65. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2011.12.006.

Rimassa L, Santoro A. Sorafenib therapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: the SHARP trial. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9(6):739–45. doi:10.1586/era.09.41.

Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(1):25–34. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7.

Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):378–90. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0708857.

Kane RC, Farrell AT, Madabushi R, Booth B, Chattopadhyay S, Sridhara R, et al. Sorafenib for the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncologist. 2009;14(1):95–100. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0185.

Yang M, Yuan JQ, Bai M, Han GH. Transarterial chemoembolization combined with sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep. 2014;41(10):6575–82. doi:10.1007/s11033-014-3541-7.

Zhang L, Hu P, Chen X, Bie P. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) plus sorafenib versus TACE for intermediate or advanced stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100305. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0100305.

Fu QH, Zhang Q, Bai XL, Hu QD, Su W, Chen YW, et al. Sorafenib enhances effects of transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140(8):1429–40. doi:10.1007/s00432-014-1684-5.

Yao X, Yan D, Zeng H, Liu D, Li H. Concurrent sorafenib therapy extends the interval to subsequent TACE for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2016;113(6):672–7. doi:10.1002/jso.24215.

Abdel-Rahman O, Elsayed ZA. Combination trans arterial chemoembolization (TACE) plus sorafenib for the management of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(12):3389–96. doi:10.1007/s10620-013-2872-x.

Muhammad A, Dhamija M, Vidyarthi G, Amodeo D, Boyd W, Miladinovic B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of traditional chemoembolization with or without sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2013;5(7):364–71. doi:10.4254/wjh.v5.i7.364.

Erhardt A, Kolligs F, Dollinger M, Schott E, Wege H, Bitzer M, et al. TACE plus sorafenib for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: results of the multicenter, phase II SOCRATES trial. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74(5):947–54. doi:10.1007/s00280-014-2568-8.

Zhang YQ, Yang JY, Wang Y, Huang YH, Fan WZ, Li JP. The analysis of the efficacy and safety of combined transarterial chemoembolization with sorafenib in patients with large hepatocellular carcinoma. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2013;93(13):987–91.

Choi GH, Shim JH, Kim MJ, Ryu MH, Ryoo BY, Kang YK, et al. Sorafenib alone versus sorafenib combined with transarterial chemoembolization for advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: results of propensity score analyses. Radiology. 2013;269(2):603–11. doi:10.1148/radiol.13130150.

Chao Y, Chung YH, Han G, Yoon JH, Yang J, Wang J, et al. The combination of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and sorafenib is well tolerated and effective in Asian patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: final results of the START trial. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(6):1458–67. doi:10.1002/ijc.29126.

Cabrera R, Pannu DS, Caridi J, Firpi RJ, Soldevila-Pico C, Morelli G, et al. The combination of sorafenib with transarterial chemoembolisation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(2):205–13. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04697.x.

Geschwind JF, Gholam PM, Goldenberg A, Mantry P, Martin RC, Piperdi B, et al. Use of Transarterial Chemoembolization (TACE) and Sorafenib in patients with Unresectable Hepatocellular carcinoma: US regional analysis of the GIDEON registry. Liver Cancer. 2016;5(1):37–46. doi:10.1159/000367757.

Zheng J, Shao G, Luo J. Analysis of survival factors in patients with intermediate-advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization combined with sorafenib. Clin Transl Oncol. 2014;16(11):1012–7. doi:10.1007/s12094-014-1189-3.

Uchino K, Obi S, Tateishi R, Sato S, Kanda M, Sato T, et al. Systemic combination therapy of intravenous continuous 5-fluorouracil and subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2a for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47(10):1152–9. doi:10.1007/s00535-012-0574-3.

Ohki T, Sato K, Yamagami M, Ito D, Yamada T, Kawanishi K, et al. Erratum to: efficacy of Transcatheter arterial Chemoembolization followed by Sorafenib for intermediate/advanced Hepatocellular carcinoma in patients in Japan: a retrospective analysis. Clin Drug Investig. 2016;36(1):93–6. doi:10.1007/s40261-015-0363-x.

Martins A, Cortez-Pinto H, Marques-Vidal P, Mendes N, Silva S, Fatela N, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2006;26(6):680–7.

Lee YH, Hsia CY, Hsu CY, Huang YH, Lin HC, Huo TI. Total tumor volume is a better marker of tumor burden in hepatocellular carcinoma defined by the Milan criteria. World J Surg. 2013;37(6):1348–55.

Fan J, Zhou J, Wu ZQ, Qiu SJ, Wang XY, Shi YH, et al. Efficacy of different treatment strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(8):1215–9.

Zhang Y, Fan W, Wang Y, Lu L, Fu S, Yang J, et al. Sorafenib with and without Transarterial Chemoembolization for advanced Hepatocellular carcinoma with main portal vein tumor thrombosis: a retrospective analysis. Oncologist. 2015;20(12):1417–24. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0196.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

The study was supported by Key Laboratory of Early Prevention and Treatment for Regional High Frequency Tumor, Ministry of Education, China (GKZ201604); Scientific Research Fund of Ministry of Health of Guangxi Province (S201513); Key project of Guangxi science and technology department (GuiKe AB16380242).

Availability of data and materials

The dataset(s) supporting the conclusions of this article is(are) included within the article and supplementary files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FXW, JC and TB contributed to study design, manuscript preparation and drafting the manuscript. SLZ, TBY, LNQ, LZ, ZHL, JZY and LQL participated in data collection, data analysis, follow-up and revising the manuscript for important contents. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Guangxi Medical University and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and internationally accepted ethical guidelines. During their admission for surgery, the patients enrolled in this study provided written informed consent for their information to be stored in hospital databases and used for research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

HCC Organized Data. The data organized from original data and used for data analysis. (XLS 55 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, FX., Chen, J., Bai, T. et al. The safety and efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization combined with sorafenib and sorafenib mono-therapy in patients with BCLC stage B/C hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer 17, 645 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3545-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3545-5