Abstract

Background

A variety of screening tools and criteria are used for the diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). As a result, the prevalence rate of GDM varied from 4.41% to 57.90% among studies from Pakistan. Beside this disagreement, similar multi-centric studies, community surveys and pooled evidence were lacking from the country. Therefore, this first systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to measure the overall and subgroup pooled estimates of GDM and explore the methodological variations among studies for any inconsistency.

Methods

Using the PRISMA guidelines, seventy studies were identified from PubMed, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar and PakMediNet database. Of them, twenty-four relevant studies were considered for systematic review and nine eligible studies selected for meta-analysis. AXIS was used for measuring quality of reporting, I^2 statistics for heterogeneity among studies and subgroups, funnel plot for reporting potential publication bias and forest plot for presenting pooled estimates.

Results

The pooled sample of nine studies was 27,034 (126 – 12,450) pregnant women, of any gestational age, from all four provinces of Pakistan. Overall pooled estimate of GDM was 16.7% (95% CI 13.1 – 21.1). The highest subgroup pooled estimate of GDM observed in studies from Balochistan (35.8%), followed by Islamabad (23.9%), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (17.2%), Sindh (13.2%), and Punjab (11.4%). The studies that adopted 75g 2-h OGTT had a little lower pooled estimate (16.3% vs. 17.3%); and that adopted diagnostic cut-off values [≥ 92 (F), ≥ 180 (1-h) and ≥ 153 (2-h)] had a greater pooled estimate (25.4% vs. 15.8%). The studies that adopted Carpenter criteria demonstrated the highest subgroup pooled estimate of GDM (26.3%), after that IADPSG criteria (25.4%), and ADA criteria (23.9%).

Conclusions

Along with poor quality of reporting, publishing in non-indexed journals and significant disagreement between studies, the prevalence rate of GDM is high in Pakistan. Consensus building among stakeholders for recommended screening methods; and continuous medical education of the physicians are much needed for a timely detection and treatment of GDM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is considered as hyperglycemia during pregnancy among women without prior history of diabetes [1]. It can adversely affect the perinatal outcomes [2]; therefore, an early diagnosis and treatment is a key to improve the prognosis and reduce the adverse outcomes [3]. Universal screening for GDM does not seem cost effective in high-income countries. However, it might be valuable in low and middle income countries [4]. A 75g 2-h oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) during 24 to 28 weeks is recommended as a gold standard method for the detection of GDM [5]. According to the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) [6], the World Health Organization (WHO) [7], and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) [5] criteria, the cut-off values for the diagnosis of GDM are ≥ 92 mg/dl after fasting, ≥ 180 mg/dl after one-hour and ≥ 153 mg/dl after two-hour. A variety of other screening tools and criteria are used for the diagnosis of GDM.

In the last two decades, several research studies have been conducted in Pakistan that measured the prevalence of GDM or compared the diagnostic accuracy of GDM screening tools. These single-center hospital-based studies utilized one of the standard or non-standard screening methods and derived a prevalence rate varying from 4.41% to 57.90% [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Beside this disagreement, similar multi-centric studies, community surveys and pooled evidence were lacking from the country. Therefore, the current study aimed to measure the overall and subgroup pooled estimates of GDM and explore the methodological variations among studies for any inconsistency.

Methods

Protocol and registration

The study protocol was not prepared or registered. However, the review is done in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [31].

Eligibility criteria

In consideration of the study outcome i.e. prevalence of GDM in Pakistan, the criteria for eligible studies were prospective observational studies, published as original research paper, in the English language, in any journal and on any date. Similarly, the criteria for eligible subjects were pregnant women of any age and gestational age, without any medical condition or history, from any socioeconomic class and any region of Pakistan.

Information sources and search process

The first author searched in PubMed, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar and PakMediNet database for eligible records during the period from December 2022 to January 2023. In PubMed advanced search, using search field title/abstract and affiliation Pakistan, the keywords “gestational diabetes mellitus or GDM” and “oral glucose tolerance test or OGTT” were entered to find the eligible records. Then the search was further refined by using the filters as follows: observational study, specie human and language English. After that the filtered studies were ordered by “best match”; and their titles were assessed for relatedness. Similar searches were made on PakMediNet, Google Scholar and ScienceDirect databases.

Screening of abstracts and full-text articles

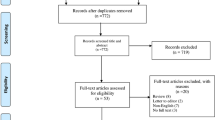

After excluding irrelevant or duplicate records (n = 46) from identified records (n = 70), the relevant studies (n = 24) were considered for systematic review. However, their abstracts were screened and the studies (n = 05) that enrolled women with hepatitis C infection, hyperuricemia, obesity or IGT were excluded. Then, their full-text manuscripts (n = 19) were screened and the studies (n = 10) that measured GDM in GCT positive cases, or had a different objective such as diagnostic accuracy studies or could not achieve the AXIS quality score > 10 were excluded. As a result, nine observational, hospital-based studies were selected for the meta-analysis, see Fig. 1. With 100% agreement (Cohen kappa = 1), both authors agreed to include/ exclude the studies in this systematic review & meta-analysis.

Quality assessment

The appraisal tool for cross-sectional studies (AXIS) [32] was adopted for measuring the quality and risk of bias within relevant studies (n = 24). The tool had twenty questions, and each question had three responses (yes, no & don’t know), increasing the score by one for each yes. Each study received a score between 0 and 20. Based on the AXIS score, the individual studies were categorized as good (> 15), fair (10—15) and poor (< 10). In addition, indexation of journals that published individual studies was evaluated for Web of Science, Scopus and Medline; and their recognition by HEC Pakistan.

Data items and collection process

The data retrieved were as follows: last name of the first author, publication date, study design & setting, sample size, screening tool, GDM diagnostic criteria, prevalence of GDM, age & gestational age of the study population, AXIS score and indexation status of the journal. The first author retrieved and extracted the data and repeated the process several times for any inconsistency. The extracted data were neither combined nor transformed. None of the authors of selected articles was approached to seek the data.

Data analysis

The data were entered using Microsoft Excel, and forest plots for overall and subgroup pooled estimates of GDM were created using the Meta-Analyst version 3.13 βeta [33]. Funnel plot for potential publication bias was created using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) [34]. The heterogeneity among studies and subgroups was measured using I^2 statistics [35]. Overall and subgroup pooled estimates of GDM were calculated using the random effects model [36].

Results

Selection process of eligible studies

Out of identified records (n = 70), the relevant studies (n = 24) were considered for systematic review. However, only 09 studies could meet the eligibility criteria, achieved AXIS quality score > 10 and selected for meta-analysis. The PRISMA flow diagram was used to indicate the methods for selecting studies, see Fig. 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

The year of publication of studies (n = 24) considered for systematic review ranged from 2002 to 2022; and of studies (n = 09) included in the meta-analysis ranged from 2015 to 2022. All included studies (n = 09) were prospective, observational, hospital-based studies published in the English language. The assessment of journals for indexation (n = 09) revealed that seven studies were published in Scopus indexed journals (two discontinued), four in WoS indexed journals, one in Medline indexed journal, six in HEC-Pak recognized journals, and two in non-indexed journals.

Six studies did not report inclusion criteria for age of study population. Four studies reported gestational age (24 to 28 weeks) of study population. Five studies reported adoption of 75g 2-h OGTT. The IADPSG and DIPSI criteria were adopted in two studies each, and the WHO, ADA, Carpenter and ACOG criteria in one study each. Noteworthy, five studies reported using the WHO, IADPSG or ADA criteria but only two of them actually adopted their cut-off values, see Table 1.

Quality/ risk of bias

All studies (n = 09) included in the meta-analysis were hospital-based, observational, with a clear objective of quantifying the burden of GDM in pregnant women without any comorbidity, and used OGTT as a screening tool. In addition, all of them achieved AXIS quality score > 10. Thus, the selection process minimized the heterogeneity among studies and subgroups to an insignificant level (I^2 < 50.0%). The publication bias was not seen in the funnel plot, see Fig. 2.

Synthesis of results

The pooled sample of nine studies was 27,034 (126 – 12,450) pregnant women, of any gestational age, from different districts of all four provinces of Pakistan. The weight allocated to individual studies varied from 0.248 to 28.006. The prevalence of GDM among included studies ranged between 8.42% and 35.80%, see Table 1. The overall pooled estimate of GDM was 16.7% (95% CI 13.1 – 21.1), which was greater than GDM reported in five individual studies and less than of four studies, see Fig. 3.

Subgroup analysis

The studies (n = 5) that adopted 75g 2-h OGTT had a little lower subgroup pooled estimate of GDM as compared to the studies (n = 4) that did not adopt or report standard OGTT (16.3% vs. 17.3%), see Fig. 4A. The studies (n = 2) that adopted diagnostic cut-off values [≥ 92 (F), ≥ 180 (1-h) and ≥ 153 (2-h)] by IADPSG, ADA and WHO had a higher subgroup pooled estimate of GDM as compared to the studies (n = 7) that adopted other or did not report diagnostic cut-off values (25.4% vs. 15.8%), see Fig. 4B. The studies that adopted Carpenter criteria demonstrated the highest subgroup pooled estimate of GDM (26.3%), after that IADPSG criteria (25.4%), and ADA criteria (23.9%), see Fig. 4C. The studies from Balochistan demonstrated the highest subgroup pooled estimate of GDM (35.8%), after that ICT Islamabad (23.9%), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (17.2%), Sindh (13.2%), and Punjab (11.4%), see Fig. 4D.

GDM in GCT positive cases

There were four studies that first utilized GCT for screening purposes and then performed 75g 2-h or 100g 3-h OGTT to diagnose GDM in GCT positive cases. Only two of them were published in HEC-Pak recognized journals and none of them could achieve AXIS score > 10. Among these studies, the prevalence of GDM ranged from 7.69% to 17.39%. Other characteristics are shown in Table 2.

GDM in women with comorbidity

There were five studies that diagnosed GDM in pregnant women having a medical condition such as hepatitis C infection, obesity, hyperuricemia or IGT. Only three of them were published in HEC-Pak recognized journals and two of them could achieve AXIS score > 10. Among these studies, surprisingly higher prevalence of GDM was observed in cases with hyperuricemia (57.90%), followed by hepatitis C (35.53%) and obese (23.70%). Other characteristics are shown in Table 3.

GDM in Diagnostic accuracy studies

There were five studies that compared the diagnostic accuracy of different screening tools including GCT, OGTT (DIPSI) or HbA1c with a 75g 2-h OGTT or 100g 3-h OGTT taking as the gold standard method for diagnosing GDM. Though all of them were published in HEC-Pak recognized journals; however, none of them could achieve AXIS score > 10. Among these studies, the prevalence of GDM ranged from 4.41% to 27.71% by OGTT (tool 1); and from 12.80% to 31.46% by other methods (tool 2). Other characteristics are shown in Table 4.

Discussion

GDM can adversely affect the pregnancy related maternal and neonatal outcomes [2]; therefore, pregnant women undergo screening for GDM during pregnancy. A variety of screening tools and criteria are used for the diagnosis of GDM. As a result, the prevalence rate of GDM varied from 4.41% to 57.90% among studies from Pakistan [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Beside this disagreement, similar multi-centric studies, community surveys and pooled evidence were lacking from the country. Therefore, this meta-analysis measured the overall pooled estimate of GDM, which was 16.7% (95% CI 13.1 – 21.1). In a meta-analysis measuring GDM prevalence in Eastern Mediterranean region, Badakhsh et al. included four studies from Pakistan and reported an equivalent subgroup pooled estimate of GDM 15.3% (95% CI 9.4 – 21.2) [37]. However, in another meta-analysis measuring GDM prevalence in Asia, Lee et al. selected two studies from Pakistan and reported a pooled prevalence 7.7% (95% CI 6.4 – 9.0) [38] that was less than half of the GDM estimated in current study. This review also revealed that the highest prevalence of GDM 57.90% was observed in pregnant women with hyperuricemia [24], which is regarded as a novel and significant risk factor of GDM [39]. Similarly, a higher prevalence of GDM 35.53% in HCV positive women [21], and ≥ 22.0% in obese women [22, 23] demonstrated that HCV infection [40] and obesity [41] had a greater risk of developing GDM. These findings suggested that pregnant women with a comorbid condition should get more attention for having higher risk of GDM.

Indexation of a journal is taken as a measure of its quality and indexed journals are regarded as having more scientific quality than non-indexed journals [42]. However, it is of a serious concern that majority of the studies included in this review could not achieve a good (> 15) quality score and were published in the non-indexed journals. Several studies did not even mention institutional ethical approval, sample size justification, sampling method, diagnostic criteria, cut-off values and/ or study limitations. Surprisingly, none of them talked about non-response rate, non-response bias and non-respondent characteristics [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30].

It is evident from the present study that there was great variation across studies in terms of study population, study design, sample selection, screening tool and diagnostic criteria. Similar concerns had been raised in other studies from Pakistan. In a nationwide cross-sectional survey, Askari et al. indicated major differences for screening, diagnosis and management of GDM among physicians, gynecologists and endocrinologists. Where 52.9% of them were practicing universal screening and 47.1% were in favor of selective screening of GDM. For the diagnosis of GDM, 40.4% of them were using estimation of plasma glucose fasting/ random, followed by 75g OGTT (25.1%), 50g GCT (20.0%), urine glucose (8.0%), HbA1c (5.2%) and 100g OGTT (1.3%) [43]. Similar results were reported by Riaz et al., where 51.43% healthcare professionals were using estimation of plasma glucose fasting (26.19%) & random (25.24%) for the diagnosis of GDM, followed by 75g OGTT (24.29%), hemoglobin A1c (9.52%), and 50g OGTT (4.29%). In addition, the authors observed lack of agreement for screening methods and management of GDM and suggested that the doctors need to be educated to adopt standard diagnostic methods and management guidelines [44].

Conclusions

Along with poor quality of reporting, publishing in non-indexed journals and significant disagreement between studies, the prevalence rate of GDM is high in Pakistan. Consensus building among stakeholders for recommended screening methods; and continuous medical education of the physicians are much needed for a timely detection and treatment of GDM.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, it is the first systematic review and meta-analysis on the topic from Pakistan. The purposive inclusion of studies having AXIS score > 10 minimized the heterogeneity among studies and subgroups to an insignificant level (I^2 < 50.0%). The study protocol was not prepared or registered. The first author retrieved and extracted the data and repeated the process several times for any inconsistency. The extracted data were neither combined nor transformed. None of the authors of selected articles was approached to seek the data.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Diagnostic criteria and classification of hyperglycaemia first detected in pregnancy: a World Health Organization Guideline. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103(3):341–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2013.10.012.

Buchanan TA, Xiang AH, Page KA. Gestational diabetes mellitus: risks and management during and after pregnancy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(11):639–49. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2012.96.

Zhuang W, Lv J, Liang Q, Chen W, Zhang S, Sun X. Adverse effects of gestational diabetes-related risk factors on pregnancy outcomes and intervention measures. Exp Ther Med. 2020;20(4):3361–7. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2020.9050.

Fitria N, van Asselt ADI, Postma MJ. Cost-effectiveness of controlling gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Eur J Health Econ. 2019;20(3):407–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-018-1006-y.

American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(Suppl 1):S20–42. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc24-S002.

International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups Consensus Panel; Metzger BE, Gabbe SG, Persson B, Buchanan TA, Catalano PA, et al. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(3):676–82. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-1848.

World Health Organization. Diagnostic criteria and classification of hyperglycaemia first detected in pregnancy. World Health Organization; 2013. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/85975.

Atta J, Das K, Yousfani ZA, Yousfani S, Bala M, Aftab S. Frequency of gestational diabetes mellitus in pregnant women: a cross-sectional study. Ann Romanian Soc Cell Biol. 2022;26(01):472–9. http://annalsofrscb.ro/index.php/journal/article/view/10819.

Latif M, Ayaz SB, Anwar M, Manzoor M, Aamir M, Bokhari SARS, et al. Frequency of gestational diabetes mellitus in pregnant women reporting to a public sector tertiary care hospital of Quetta. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2022;72(6):2095–8. https://doi.org/10.51253/pafmj.v72i6.4073.

Gul B, Mehboob S, Qayuom S, Daud M. The prevalence of gestational diabetes in women of child bearing age belonging to KPK. Khyber J Med Sci. 2021;14(4):243–8. https://kjms.com.pk/index.php/kjms/article/view/309.

Faisal M, Bakar MA, Hussain Z, Abbas K. The frequency of gestational diabetes mellitus among pregnant mothers admitted in gynaecology/obstetrics ward of Sheikh Zayed Hospital Rahim Yar Khan, Pakistan. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2018;7(7):2608–11. https://doi.org/10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20182506.

Khan N, Farooq N, Batool A, Altaf A. Frequency of gestational diabetes mellitus and associated risk factors. Rawal Med J. 2018;43(3):459–61. http://www.rmj.org.pk/fulltext/27-1511803407.pdf

Riaz M, Nawaz A, Masood SN, Fawwad A, Basit A, Shera AS. Frequency of gestational diabetes mellitus using DIPSI criteria, a study from Pakistan. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2019;7(2):218–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2018.06.003.

Ahmad NM, Shahid MA, Gulzar A, Ahmad M, Khan AS. Frequency of gestational diabetes mellitus among pregnant women. Pak J Med Health Sci. 2018:12(4):1720–2. https://pjmhsonline.com/2018/oct_dec/pdf/1720.pdf

Fatima SS, Rehman R, Alam F, Madhani S, Chaudhry B, Khan TA. Gestational diabetes mellitus and the predisposing factors. J Pak Med Assoc. 2017;67(2):261–5. https://jpma.org.pk/PdfDownload/8088.

Bibi S, Saleem U, Mahsood N. The frequency of gestational diabetes mellitus and associated risk factors at Khyber teaching hospital Peshawar. J Postgrad Med Inst. 2015;29(1):43–6. https://www.jpmi.org.pk/index.php/jpmi/article/view/1670.

Sohag AA, Memon S, Bhutto A. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus and its association with risk factors. Medical Channel. 2013;19(2):30–2.

Jaleel R. Gestational diabetes mellitus: Selective versus universal screening. Pak J Surg. 2009;25(4):290–4. https://www.pjs.com.pk/journal_pdfs/oct_dec09/18-Diabetes%20Mellitus.pdf

Hassan A. Screening of pregnant women for gestational diabetes mellitus. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2005;17(2):54–8. http://www.demo.ayubmed.edu.pk/index.php/jamc/article/view/4168/2551.

Javaid K, Sohail R, Zaman F. Screening for gestational diabetes. J Surg Pak. 2002;7(4):5–7. http://old.jsp.org.pk/Issues/Old%20Issues%20from%201996%20to%202007/JSP%20PDF%202002/JSP%207%20(3)%20October%20%20-%20December%202002.pdf#page=6

Qamar TA, Naz U, Hira AK, Naz U, Jabbar S, Kazi S. Frequency of gestational diabetes in pregnant women with hepatitis C in Civil Hospital Karachi. Pak J Med Health Sci. 2022;16(10):603–5. https://doi.org/10.53350/pjmhs221610603.

Hafeez S, Shakeel S, Shakeel T. Frequency of pregnancy induced gestational diabetes mellitus and hypertension in obstetrics. World J Pharm Med Res. 2020;6(1):251–4. https://www.wjpmr.com/home/article_abstract/2549.

Sahibzada H, Ullah I, Yousaf S, Rehana T. Frequency of gestational diabetes in obese patients. Khyber J Med Sci. 2020;13(2):300–3. https://kjms.com.pk/old/content/volume-13-may-august-2020-no-2.

Ismail A, Amin N, Baqai S. To measure the frequency of gestational diabetes mellitus in patients with raised serum uric acid level in first trimester of pregnancy. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2019;69(3):545–8. https://www.pafmj.org/index.php/PAFMJ/article/view/3024.

Ali A, Munir AH, Rafiq A. Gestational diabetes in women presenting to teaching hospitals in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. J Med Sci. 2018;26(1):14–7. https://jmedsci.com/index.php/Jmedsci/article/view/485.

Ismail S, Perveen S, Jabbar S, Sheikh AH. Predictive value of diabetes in pregnancy study group of India test for gestational diabetes mellitus. J Surg Pak. 2022;27(2):41–5. http://jsp.org.pk/index.php/jsp/article/view/314.

Masood SN, Lakho N, Saeed S, Masood Y. Non-fasting OGTT versus fasting OGTT for screening of hyperglycaemia in pregnancy (HIP). Pak J Med Sci. 2021;37(4):1008–13. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.37.4.3979.

Arif A, Nazar S, Arif S. Efficacy of 50g glucose challenge test as a screening tool for gestational diabetes mellitus. J Bahria Univ Med Dent Coll. 2016;6(1):14–7. https://jbumdc.bahria.edu.pk/index.php/ojs/article/view/151.

Khan SH, Manzoor R, Baig AH, Tariq B, Ayub N, Sarwar S, et al. Role of HbA1c in diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus. J Pak Med Assoc. 2020;70(10):1731–6. https://jpma.org.pk/article-details/10156?article_id=10156.

Fatima A, Tanveer Q, Naz M. Accuracy of glucose challenge test in screening of gestational diabetes mellitus. J Univ Med Dent Coll. 2018;9(3):31–5. https://www.jumdc.com/index.php/jumdc/article/view/88.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):89. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4.

Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open. 2016;6(12): e011458. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458.

Wallace BC, Schmid CH, Lau J, Trikalinos TA. Meta-Analyst: software for meta-analysis of binary, continuous and diagnostic data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:80. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-80.

Borenstein M. Comprehensive meta-analysis software. In: Egger M, Higgins JP, Smith GD, editors. Systematic Reviews in Health Research: Meta-analysis in Context. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119099369.ch27

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. https://www.bmj.com/content/327/7414/557.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(2):97–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.12.

Badakhsh M, Daneshi F, Abavisani M, Rafiemanesh H, Bouya S, Sheyback M, et al. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in Eastern Mediterranean region: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine. 2019;65(3):505–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-019-02026-4.

Lee KW, Ching SM, Ramachandran V, Yee A, Hoo FK, Chia YC, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of gestational diabetes mellitus in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):494. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2131-4.

Zhao Y, Zhao Y, Fan K, Jin L. Serum uric acid in early pregnancy and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a cohort study of 85,609 pregnant women. Diabetes Metab. 2022;48(3):101293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2021.101293.

Rezk M, Omar Z. Deleterious impact of maternal hepatitis-C viral infection on maternal and fetal outcome: a 5-year prospective study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;296(6):1097–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-017-4550-2.

Yen IW, Lee CN, Lin MW, Fan KC, Wei JN, Chen KY, et al. Overweight and obesity are associated with clustering of metabolic risk factors in early pregnancy and the risk of GDM. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(12):e0225978. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225978.

Balhara YP. Indexed journal: What does it mean? Lung India. 2012;29(2):193. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-2113.95345.

Askari S, Riaz M, Basit A. Health care professionals perspective regarding gestational diabetes mellitus in Pakistan: Are clinicians on the right track?. Pak J Med Res. 2019;58(3):127–33. https://www.pjmr.org.pk/index.php/pjmr/article/view/8.

Riaz SH, Khan MS, Jawa A, Hassan M, Akram J. Lack of uniformity in screening, diagnosis and management of gestational diabetes mellitus among health practitioners across major cities of Pakistan. Pak J Med Sci. 2018;34(2):300–4. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.342.12213.

Funding

This research study received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AdM: Concept; Data extraction, entry, & interpretation; Manuscript writing, review and revision; Read, approve and accountable for final submission. AaM: Data analysis & interpretation; Manuscript review and revision; Read, approve and accountable for final submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Adnan, M., Aasim, M. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in Pakistan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 24, 108 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-024-06290-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-024-06290-9