Abstract

Background

Maternal multiple long-term conditions are associated with adverse outcomes for mother and child. We conducted a qualitative study to inform a core outcome set for studies of pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions.

Methods

Women with two or more pre-existing long-term physical or mental health conditions, who had been pregnant in the last five years or planning a pregnancy, their partners and health care professionals were eligible. Recruitment was through social media, patients and health care professionals’ organisations and personal contacts. Participants who contacted the study team were purposively sampled for maximum variation. Three virtual focus groups were conducted from December 2021 to March 2022 in the United Kingdom: (i) health care professionals (n = 8), (ii) women with multiple long-term conditions (n = 6), and (iii) women with multiple long-term conditions (n = 6) and partners (n = 2). There was representation from women with 20 different physical health conditions and four mental health conditions; health care professionals from obstetrics, obstetric/maternal medicine, midwifery, neonatology, perinatal psychiatry, and general practice. Participants were asked what outcomes should be reported in all studies of pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions. Inductive thematic analysis was conducted. Outcomes identified in the focus groups were mapped to those identified in a systematic literature search in the core outcome set development.

Results

The focus groups identified 63 outcomes, including maternal (n = 43), children’s (n = 16) and health care utilisation (n = 4) outcomes. Twenty-eight outcomes were new when mapped to the systematic literature search. Outcomes considered important were generally similar across stakeholder groups. Women emphasised outcomes related to care processes, such as information sharing when transitioning between health care teams and stages of pregnancy (continuity of care). Both women and partners wanted to be involved in care decisions and to feel informed of the risks to the pregnancy and baby. Health care professionals additionally prioritised non-clinical outcomes, including quality of life and financial implications for the women; and longer-term outcomes, such as children’s developmental outcomes.

Conclusions

The findings will inform the design of a core outcome set. Participants’ experiences provided useful insights of how maternity care for pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions can be improved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Women with long-term conditions are at higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes [1, 2]. Pregnancy can also impact on women’s underlying long-term conditions [3]. These challenges are likely to be multiplied in women who have two or more long-term conditions, also known as multimorbidity or multiple long-term conditions [4]. They may have to take multiple medications [5] or attend appointments with different health care teams to manage their multiple long-term conditions [6]. Recent studies suggest that maternal multiple long-term conditions are associated with higher risk of adverse outcomes such as preterm birth [7, 8]. This is significant as one in five pregnant women has multiple long-term conditions in the United Kingdom (UK) [9]. Current health care systems and guidelines are configured for single health conditions [10]. Therefore maternal multiple long-term conditions present a unique challenge to pregnancy and is a priority for maternity research [11].

An outcome is a measurement or observation used to assess the effect of an intervention or an exposure (in this case maternal multiple long-term conditions) to the health and well-being of the population of interest [12, 13]. The MuM-PreDiCT consortium is developing a core outcome set for studies of pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions [14]. This minimum set of outcomes is recommended to be reported in all studies in this field to enable comparison between studies and combining of information in systematic reviews and meta-analyses [15]. To ensure its relevance, the core outcome set is being developed with multiple stakeholders, including pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions and health care professionals.

The study protocol for the core outcome set has been reported elsewhere, [14] but briefly it involves a four stage process: systematic literature search and focus groups to generate an initial list of outcomes, followed by prioritisation through Delphi surveys and a consensus setting meeting [14].

Systematic reviews of outcomes reported in previous literature may not represent the views of key stakeholders, especially service users [13]. Our systematic literature search did not identify qualitative studies of pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions. The Core Outcome Measures for Effectiveness Trials (COMET) Handbook recommends supplementing the initial list of outcomes with qualitative studies involving key stakeholders [13]. The words participants used to describe their views and experiences can subsequently be used to label and explain outcome items in the Delphi surveys [13, 16].

This focus group study aims to explore outcomes that women, partners and health care professionals feel should be reported in all studies of pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions. The findings will inform the design of a Delphi survey for a core outcome set for studies or pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions.

Methods

Study design

Interviews and focus groups have been used as qualitative methods to inform core outcome sets [16]. As the experience and outcomes of pregnancy may vary depending on the women’s unique combination of health conditions, we chose to conduct focus groups for synergistic discussions [16].

Inclusivity statement

Where the words ‘women’, ‘maternal’, or ‘mother’ are used, these also include people who do not identify as women but have been pregnant, planning to be pregnant or have given birth.

Inclusion criteria

Participants were eligible for the focus groups if they were women with two or more pre-existing long-term physical or mental health conditions, who have been pregnant in the last 5 years or are planning a pregnancy; their partners; and health care professionals who look after pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions and their children. Participants had to be able to converse in English and based in the UK.

Recruitment

We planned to conduct three focus groups, one for health care professionals, one for women, and one for women with or without their partners. After discussion with our patient and public involvement (PPI) advisory group, we aimed to recruit eight participants per focus group to facilitate optimal discussion and to account for dropouts. The PPI advisory group also recommended inviting partners to attend alongside their pregnant partner, instead of a focus group for partners only. This would help focus the discussion on outcomes relevant to studies of pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions.

Recruitment and sampling was guided by a sampling matrix prespecified in the core outcome set protocol, based on physical or mental health conditions, ethnicity, under-served populations and specialties of health care professionals [14]. We additionally aimed for representation from all four devolved nations in the UK and partners.

Study adverts were shared through social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and websites) of charities and organisations for patients, pregnancy, mothers, and health care professionals, and with personal contacts of the multidisciplinary research team. The recruitment campaign took place in October 2021 for health care professionals and January 2022 for women and partners, and lasted for two to three months. Potential participants contacted the research team directly and were provided with the participant information sheets. They completed a sampling questionnaire which iteratively informed the recruitment strategy [14]. We then undertook maximum variation purposive sampling from the pool of eligible potential participants [16].

Data collection

The initial topic guide was developed based on the study aim and previous qualitative studies for core outcome set development in obstetrics [16,17,18]. This was then reviewed by and pilot tested (test run of a group discussion) with our patient and public involvement (PPI) advisory group. The discussion in the pilot test focused on maternity care experiences and proposed solution. In order to efficiently draw out discussions on outcomes, the PPI advisory group advised that the topic guide was simplified to an open question of what outcomes are important to stakeholders, and included a case vignette to illustrate what is an outcome. The topic guide was then revised based on their feedback (Supplementary Material 1).

Three focus groups were conducted from December 2021 to March 2022, one for each of the following groups:

-

(1)

health care professionals,

-

(2)

women with multiple long-term conditions, and

-

(3)

women with multiple long-term conditions with or without their partners.

Due to difficulties with face-to-face meetings during the COVID-19 pandemic, the focus groups were conducted virtually using Zoom and audio recorded.

The lead facilitator (SIL) is a female doctoral student, public health specialist trainee and qualified as a general practitioner. She has previously undertaken qualitative data analysis and training in qualitative research. The supporting team included researchers with expertise in qualitative research in health service, public health and maternity.

The health care professionals’ focus group was planned for one hour to increase participation rate, based on feedback from potential participants. There were two facilitators: one led the discussion whilst one monitored the chat function. To build rapport with the participants, the lead facilitator shared her clinical background.

The two women and partners’ focus groups each lasted two hours. There were three facilitators, the additional clinical facilitator was designated to provide support should participants become distressed. Women and partners were emailed a £25 e-voucher each for reimbursement. The lead facilitator shared her medical history (long-term condition) and characteristics of under-served populations (physical disability and ethnic minority) with the participants. To encourage participants to speak freely, the facilitators did not share their clinical background. After each focus group, the facilitators debriefed and reflected on their initial impressions.

Analysis

Thematic analysis was conducted with an inductive approach [19]. The analysis focused on research outcomes discussed or inferred by participants. The stages of pregnancy were used as a prompt to facilitate the focus group discussions. Therefore, we pre-specified that themes (outcomes) will be provisionally categorised by the different stages of pregnancy (before, during and after pregnancy) and by maternal and children’s outcomes.

The audio recordings of the focus groups were transcribed verbatim by SIL. This allowed for familiarisation with the data. Two researchers coded the transcripts independently, the initial codes were collated into potential themes using NVivo 12 and Microsoft Word. The codes and themes / outcomes were then compared and discussed. Themes identified from the focus groups of health care professionals and women/partners were compared and contrasted in tabular form.

Further checking was conducted by a multidisciplinary team, including MB (obstetrician), ZV (midwife) and RP (woman’s representative) who read the transcripts and reviewed the developed themes. The key themes with extracted quotes were presented to our PPI advisory group, with their opinions sought on key queries, especially on the labelling of themes. This approach helped maintain researcher reflexivity [20] and enriched the analysis. The outcomes identified in the focus groups were then compared with the list of outcomes identified in a systematic literature search.

Patient and public involvement

The PPI advisory group advised on the study design and recruitment strategy, design of the recruitment materials (e.g. participant information sheets and study poster) and shared the study advert through their networks. They pilot tested the topic guide and was involved in interpreting the data analysis. A PPI co-investigator (RP) reviewed the anonymised transcripts against the key themes identified. The final manuscript was reviewed by PPI co-investigators (RP and NM).

Results

Characteristics of study participants

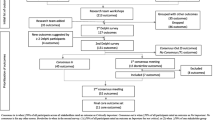

Supplementary Material 2 presents the participant flow chart. Nineteen health care professionals expressed interest and were eligible, 10 were available on the scheduled focus group date and were invited to participate. Three health care professionals who expressed interest thereafter were kept on the waiting list and all were eventually invited to participate as five original participants could not attend. Twenty-five women expressed interest and were available on the focus group dates, 18 were invited to participate based on the sampling frame, subsequently six could not attend. Overall, eight health care professionals, 12 women and two partners participated in one of the three focus groups. Table 1 presents the characteristics of study participants for each focus group. There was representation from health care professionals from obstetrics, obstetric/maternal medicine, midwifery, neonatology, perinatal psychiatry, and general practice; and women with 20 different physical health conditions and four mental health conditions.

Thematic categories

Table 2 presents the coding tree consisting of thematic categories, themes / outcomes and subthemes. Five thematic categories were identified: (i) Care Outcomes, (ii) Clinical Outcomes, (iii) Role as mothers or parents, (iv) Other outcomes, and (v) Consideration for future studies. An overview of the thematic categories is presented here with selected quotes, with supplementary quotes in Supplementary Material 3.

Care outcomes

Participants highlighted stages of pregnancy where input from health and social care professionals were important. Preconception counselling was important to plan whether women have to change or stop medications they take for their long-term conditions. Women and health care professionals felt that postnatal support should be longer than the conventional six weeks given the complexity of women’s multiple long-term conditions. Women may need support looking after their newborn baby, whilst managing their multiple long-term conditions that may have been adversely impacted by the pregnancy. Key care outcomes were whether the relevant components of care were provided and of good quality.

Specific components of care were discussed at length. Examples relevant to women with multiple long-term conditions included: multidisciplinary coordination of care, holistic care and continuity of care. Health care professionals said that women want to know whether they or their baby will need to have more appointments or tests than routine care. Women described the burden of having to attend multiple appointments with different specialties and want more coordinated care. Continuity of care included transfer of information as women and their baby transitioned through different teams (e.g., specialist team to general team) and different stages of pregnancy. They valued seeing the same health care professionals throughout pregnancy:

“I had a fantastic consultant…he was there throughout ...an advocate who knew all my health conditions, he led on one of them, but he knew the others and linked up with my other doctors.” (FG2, women [W]4)

Feeling informed of their care and conditions was an outcome that was frequently discussed. Women and partners valued honest communication of potential risk to their pregnancy and baby. They want to be informed of: what is happening during birth, the side effects of medication in pregnancy, actions they can take for self-care, and support or services available for their specific needs. Being sufficiently informed was crucial in helping them mentally prepare to face adverse outcomes.

“…I needed to prepare myself, psychologically for the possibility that the baby might not be able to stay with me [after birth]…having that information before…made it easier for me to manage ...” (FG3, W4)

Women shared accounts of when they experienced discrimination due to health care professional’s attitudes, to illustrate respectful care as an important outcome.

“…they said…how are you going to manage to look after your child…because disabled women are seen as…not basically being suitable for having children that we just get completely bypassed.” (FG2, W2)

Having maternity services that were accessible was an important structural measure of care. One participant shared experiences of encountering physical (e.g., lack of wheelchair access), social (e.g., domestic violence) and communication barriers (e.g., lack of sign language interpreters).

Health care professionals and women spoke about women’s desire to have minimal intervention during pregnancy and to their baby. However, the care needs arising from pregnant women’s multiple long-term conditions may limit their birthing and care options. Women described the devastation of being separated from their newborn who required additional support after birth. These are outcomes that health care professionals would like to see being studied so they can counsel women. Despite the limitations of options, feeling involved in their care decision is an important outcome, as one participant shared her experience when this did not happen:

“…the consultant…goes, we just had a meeting and we decided that you cannot have a [type of birth]…I go…all…of you should be in here now, because you made decisions without me.” (FG2, W1)

Women spoke about the importance of measuring their experience of care, throughout the pregnancy and specifically during birth, and whether there was any birth injuries. Despite being involved in their birth plans, non-adherence by the care team can lead to women having negative birth experience. One disabled participant spoke about how difficult births may not relate to the obstetric factors, but stemmed from the women not being listened to.

“…the main outcomes that need to be looked at are satisfaction with experience…birth satisfaction…I know a lot of people who’ve been through some very difficult births and it’s not related to the difficulties. It’s related to…not being listened to, not being allowed adequate pain relief…not having their physical or mental health concerns taken into account.” (FG2, W2)

Clinical outcomes

Participants spoke about clinical outcomes such as maternal death, stillbirth, infant mortality and preterm birth. Clinical outcomes that were specific to pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions included the impact of pregnancy on the women’s long-term conditions (e.g., improvement in or worsening pain in inflammatory arthritis), the development of new health conditions (e.g., type 2 diabetes), and whether children inherited their mothers’ long-term conditions.

One area of particular interest was the impact of medication in pregnancy. Availability of information on medication safety in pregnancy was important to women. Health care professionals felt it was important to measure the extent of non-adherence to medications as some women may stop their regular medications when pregnant or breastfeeding because of concerns about how the medications may affect their baby. Women struggled to articulate specific outcomes they were concerned about, but mentioned miscarriage, birth defects and baby’s condition at birth. Health care professionals emphasised the importance of balanced discussion with women:

“…it’s helpful to know the effects of…untreated…disease on the outcomes of the children so that you can weigh up the benefits and the risks of taking medication...” (FG1, health care professionals [HCP]1)

Perinatal mental illness, emotional and mental wellbeing, and satisfaction with perinatal mental health support were identified as important outcomes. Health care professionals and women discussed how mental and physical health conditions are interlinked and can influence each other. They spoke about the emotional stress that women experienced long after the birthing event and hence the importance of receiving good perinatal mental health support. One participant highlighted that mental illness is a taboo in some ethnic minority groups, which may impede access to diagnoses and support. Women shared their experience of not having satisfactory perinatal mental health support:

“I’ve had serious and complicated mental health issues, since our…[child] was born and I still have never been referred to community psychiatry. I got a very reluctant acceptance through [the] perinatal mental health [team]…” (FG3, W2)

Role as mothers or parents

Both health care professionals and women participants spoke about the pressure women felt to be the perfect mother and to breastfeed. Where there were adverse child outcomes, health care professionals and women participants spoke of the guilt some pregnant women experienced, as they attributed the adverse child outcomes to their own long-term conditions or the medications they have to take. Women spoke about how circumstances around birth may disrupt parent (including the father) and infant bonding. Health care professionals discussed that mother and infant bonding and the ability to engage with parental roles could be outcomes to measure when evaluating an intervention. For example, in perinatal psychiatry:

“destabilization of [the women’s] mental health [can lead to] potential disruption to mum, to baby, to the bond…[disruption to] establishing feeding…” (FG1, HCP8).

Other outcomes

One of the key themes in this category was how the pregnancies of women with multiple long-term conditions impacted on their partner. Women described the carer role that their partner take on, to help them with their activities of daily living or managing their long-term conditions. Partners want to be informed of actions they can take to look after mother and baby. Women spoke of the emotional stress their partner experienced during the childbirth process, as they were fearful of what might happen to the women. Partners shared contrasting experience of their involvement in the care of the pregnant women.

“…We’re just the people who drive them there… we’re constantly left where we may have to pick up the pieces of whatever has happened…I’ve just been ignored by doctors.” (FG3, Partner [P]1)

“…the nurses were keeping me well assured about what was going on…Even though you were freaking out… you’re always well informed…” (FG3, P2)

Consequently, whether partners felt they were involved and supported, in addition to their emotional and mental wellbeing were identified as important outcomes.

Considerations for future studies

Health care professionals raised some considerations for future studies of pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions. This included assessing how outcomes may differ by ethnicity.

One health care professional spoke about framing outcomes in a positive way:

“…the impacts that we’re considering for multiple morbidities are always negative…I wonder if we could have positive impacts. Having had a baby, people feel so much happier and better. They didn’t think it was going to go well, but actually it did…” (FG1, HCP3)

Health care professionals discussed that maternal and children’s outcomes will vary greatly, depending on the women’s long-term conditions. Sometimes women’s outcome expectations may not be achievable. Therefore, core outcomes for studies of pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions should reflect experiences and not just binary outcomes:

“…I may recommend you not to get pregnant, because your risk…is so high, you may choose to get pregnant, but the satisfaction should be… you felt supported… whether your expectation has been met or not.” (FG1, HCP4)

Outcomes by stakeholder groups

Table 3 tabulates the 63 outcomes by stakeholder groups. These were presented by maternal (43 outcomes) and children’s outcomes (16 outcomes), health care utilisation (4 outcomes) and by the stages of pregnancy.

Comparison with outcomes reported in the literature

For the core outcome set development, our systematic literature search [14] included two core outcome sets for maternity care, pregnancy and childbirth, [21, 22] one core outcome set for multiple long-term conditions [23] and 26 studies of pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions, [7, 8, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47] which reported 185 outcomes. When mapped to these outcomes reported in the literature, this focus group study identified an additional 28 outcomes (Table 4).

Discussion

Main findings

We explored research outcomes that are important to women with multiple long-term conditions who have been pregnant or who are planning a pregnancy, partners and health care professionals. In comparison to outcomes identified from a systematic literature search, our focus groups identified an additional 28 outcomes. Outcomes considered important were generally similar across stakeholder groups. Women emphasised on outcomes related to care processes and wanted to feel informed of the risks to their pregnancy, their health conditions and their baby. Partners said it was important to be informed of risks to the pregnant women and what they can do to look after mother and baby, and to feel involved in their care. Health care professionals additionally prioritised non-clinical outcomes, such as quality of life and financial implications for the women; and longer-term outcomes, especially for children, such as developmental outcomes.

Comparison with the literature

Medication in pregnancy

Medication in pregnancy may be a particular challenge for pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions as they may have to take many different medications [48]. In the focus groups, women specifically wanted information on medication safety in pregnancy and were concerned about the general risks on their babies. This is consistent with findings from studies of pregnant women with single long-term conditions [49,50,51,52,53,54]. However, within the focus groups, it was difficult to elicit specific outcomes that women were worried about for their children in relation to medication use. Other qualitative studies about medication in pregnancy have reported that women are concerned specifically about the effect of medication on fetal development, congenital anomalies and developmental disability [51, 53,54,55]. Our health care professional participants expressed concerns about attributing observed adverse outcomes to fetal exposures in utero; or to suboptimal management of maternal health conditions.

Aspects of care

Previous literature on single long-term condition in pregnant women reveal several aspects of care that were also important to our participants. Women with inflammatory arthritis spoke about needing to time their conception and to adjust their medications, [51] highlighting the importance of preconception planning.

Earlier work on women with long-term conditions described their feeling of abandonment by health care professionals after giving birth [6]. They felt that their long-term conditions affected their ability to look after their babies [51,52,53]. The need for longer postnatal support was discussed both by women and health care professionals.

Studies suggest that women with long-term conditions may be more likely to develop perinatal mental illness [28, 56]. Here, health care professionals discussed the importance of providing perinatal mental health support because of their understanding of the link between maternal mental illness and maternal bonding with the baby.

Women with long-term conditions described their experience of fragmented clinical care, meaning they took on the role of relaying information between different health care professionals [6]. Women also shared experiences of feeling discriminated against by health care professionals through the language used and how they were treated. In Rebić et al’s systematic review on key challenges of pregnancy with inflammatory arthritis, women described facing ‘judgement’ from the community and health care professionals for their pregnancy intention and ability to fulfil parental responsibility [51].

Single versus multiple long-term conditions

Our focus group did not include pregnant women with no or single long-term conditions for comparison with pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions. However, the findings in this study is likely to be common to all women who have been pregnant or given birth, with or without multiple long-term conditions. This is reflected by the overlap of findings with existing core outcome sets for all pregnancies in general [21, 22] and with studies of pregnant women with single condition [49,50,51,52,53,54]. A few of our findings are specific to pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions, such as quality of life, number of appointments and hospital admission (treatment burden), and development of new long-term conditions, as observed in the core outcome set for multimorbidity [23].

There is currently no qualitative study specific to pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions. Hansen et al. interviewed pregnant women with one or more long-term conditions in Denmark [6]. Although just under half of the study participants had two or more long-term conditions, it was not possible to disentangle the findings for those with (two or more conditions) and without (single conditions) multiple long-term conditions. Their experience is likely to be similar as even pregnant women with single condition still have to see multiple health care professionals (e.g. obstetrics, anaesthetist, and specialist for their long-term conditions) and balance the risk to their long-term conditions, pregnancy, and unborn child. However, the complexity and treatment burden is likely to be heighten when there are more than one long-term conditions to account for in the pregnancy care plan.

Strengths and limitations

Representation of stakeholders

This focus group study involved a wide range of stakeholders, including health care professionals from different specialties, women with different long-term conditions, both who have had experience of pregnancy, childbirth and those who are planning a pregnancy, and their partners. In line with other qualitative studies in core outcome set development, we have included more service users than health care professionals to identify outcomes [57]. This is to ensure outcomes preferred by service users are included in subsequent prioritisation methods [57].

This study included the perspective of partners, who may be a family member or take on the role of a carer. Previous studies have also included the perspectives of carers as ‘involved witnesses’ [16]. The presence of partners may enhance or inhibit the disclosure by women participants and vice versa. To partially account for this, one focus group was dedicated to women participants only. We did not conduct a focus group for partners only, and therefore may not have fully captured their views. However, in the focus group where two partners participated, there were discussions specifically around the impact of pregnancies of women with multiple long-term conditions, on partners and the family unit.

A key limitation of this study is the small sample size. As this study is part of a mixed-method core outcome set development and wider work of the MuM-PreDiCT consortium, within the available resources and project timeline, we only conducted three focus groups. The number of focus groups was not guided by data saturation. Despite using a maximum variation sampling strategy, it was not possible to have representation from all health conditions. It was also challenging to recruit partners. Therefore, it is possible that we have not captured all outcomes that are important to key stakeholders.

However, the literature search has already identified a long comprehensive list of reported outcomes. It included core outcome sets of pregnancy, childbirth and maternity care in general, [21, 22] which were developed with service users and overlapped with many outcomes identified in this focus group. In addition, there will be opportunities for participants to suggest missing outcomes in the Delphi survey.

Participants were limited to those that could converse in English and in the UK. This limits the transferability of the study findings to non-English speaking pregnant women within the UK and other countries with different health care system, especially low-middle income countries.

Data collection

Qualitative methods used to inform core outcome set development included interviews, focus groups and secondary analysis of archived qualitative studies [16, 17]. In this focus group study, we observed that participants were empowered to share their feelings and experiences after listening to other participant’s stories, especially those with under-served characteristics or negative care experiences. However, some participants may find focus groups to be intimidating and inhibitive [16]. To overcome this, we harnessed the advantages of an online platform. Two participants chose to communicate using the chat function and had their camera turned off. A distress protocol was in place and a designated facilitator checked in on participants when required.

The online platform also helped overcome the logistic challenges of convening a group from different geographical location, people with clinical duties or childcare responsibilities. However, this together with the social media focused advertisement, may have led to digital exclusion.

A short video designed by the COMET group, explaining what a core outcome set is, [15] was shared with study participants before the focus groups. Based on pilot testing with our PPI advisory group, we used a case scenario to illustrate the concept of outcome. Nevertheless, the focus group discussions still focused on care experiences and processes. This issue was also encountered in other studies [16]. Through reflections after each focus group, the lead facilitator reframed participant’s views or experiences into follow up questions about outcomes.

Data analysis

The lead facilitator, who also analysed the data, is medically trained. This may have biased her views in favour of health care professional’s position, when interpreting themes relating to participant’s perceived quality of care. She also conducted the systematic literature search compiling outcomes reported in the literature. This exposure to the literature may have influenced how she labelled the outcomes identified in this study. However, these potential biases are counter balanced by her dual role of having lived experience of a long-term condition, the input of a second facilitator and data analyst with no medical training and no prior exposure to the literature search, and extensive involvement of the PPI advisory group in interpreting the data.

Previous qualitative studies in core outcome set development have used different analyses approaches, including thematic analysis, framework approach and approach informed by grounded theory [57,58,59,60,61]. Recent studies used interpretive evidence synthesis methods to transform participants’ experiences and views into measurable outcomes [62, 63]. We undertook thematic analysis using a data driven approach but also ensured we addressed the research question. The term ‘outcomes’ was used in a broad way to capture some aspects of experience that were important to stakeholders, even if they are not easily measurable with existing measurement tools, or do not fit with traditional medical understandings of ‘outcomes’.

When designing the Delphi survey, there was further deliberations with the multidisciplinary research team on combining outcome categories and labelling outcomes. Where possible, when preparing the plain English summary of the Delphi survey, we used the subthemes and words used by participants in this focus group study.

Implications for future research

The outcomes identified in this focus group will inform the design of a Delphi survey to develop a core outcome set for future studies of pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions.

Future studies should explore ethnic inequality in pregnancy outcomes as suggested by one participant. Another participant suggested considering positive outcomes. This concept was previously discussed by Smith et al. who examined salutogenically focused outcomes of intrapartum interventions in systematic reviews [64]. The authors suggested shifting towards optimum or positive outcomes (health and wellbeing) instead of focusing on averting adverse outcomes [64].

Although we focused on research outcomes, the rich description of women’s experience of maternity care provided pointers of good clinical practice for health care professionals providing care to pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions and their children. This will be explored further in MuM-PreDiCT’s upcoming interview study on the experience of maternity care of pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions.

Conclusions

Women with multiple long-term conditions emphasised outcomes related to the maternity care they received. Both women and their partners prioritised how better involvement in their care through enhanced communication and information sharing would help their experiences at different stages of pregnancy. These findings will inform the design of a standardised core outcome set for studies of pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions. However, women’s experiences also provide useful insights into broader ways in which maternity care for pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions can be improved without additional costs.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary materials.

Abbreviations

- COMET:

-

Core Outcome Measures for Effectiveness Trials

- FG:

-

Focus group

- HCP:

-

Health care professionals

- PPI:

-

Patient and public involvement

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- W:

-

Women

References

Roos-Hesselink J, Baris L, Johnson M, De Backer J, Otto C, Marelli A, Jondeau G, Budts W, Grewal J, Sliwa K, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women with cardiovascular disease: evolving trends over 10 years in the ESC Registry of pregnancy and cardiac disease (ROPAC). Eur Heart J. 2019;40(47):3848–55.

Viale L, Allotey J, Cheong-See F, Arroyo-Manzano D, McCorry D, Bagary M, Mignini L, Khan KS, Zamora J, Thangaratinam S. Epilepsy in pregnancy and reproductive outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet (London England). 2015;386(10006):1845–52.

Wiles K, Webster P, Seed PT, Bennett-Richards K, Bramham K, Brunskill N, Carr S, Hall M, Khan R, Nelson-Piercy C, et al. The impact of chronic kidney disease stages 3–5 on pregnancy outcomes. Nephrol Dialysis Transplantation. 2020;36(11):2008–17.

The Academy of Medical Sciences. : Multimorbidity: a priority for global health research. In.; 2018.

Subramanian A, Azcoaga-Lorenzo A, Anand A, Phillips K, Lee SI, Cockburn N, Fagbamigbe AF, Damase-Michel C, Yau C, McCowan C, et al. Polypharmacy during pregnancy and associated risk factors: a retrospective analysis of 577 medication exposures among 1.5 million pregnancies in the UK, 2000–2019. BMC Med. 2023;21(1):21.

Hansen MK, Midtgaard J, Hegaard HK, Broberg L, de Wolff MG. Monitored but not sufficiently guided – a qualitative descriptive interview study of maternity care experiences and needs in women with chronic medical conditions. Midwifery. 2022;104:103167.

Admon LK, Winkelman TNA, Heisler M, Dalton VK. Obstetric outcomes and delivery-related Health Care utilization and costs among pregnant women with multiple chronic conditions. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:E21.

D’Arcy R, Knight M, Mackillop L. A retrospective audit of the socio-demographic characteristics and pregnancy outcomes for all women with multiple medical problems giving birth at a tertiary hospital in the UK in 2016. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2019;126:128.

Lee SI, Azcoaga-Lorenzo A, Agrawal U, Kennedy JI, Fagbamigbe AF, Hope H, Subramanian A, Anand A, Taylor B, Nelson-Piercy C, et al. Epidemiology of pre-existing multimorbidity in pregnant women in the UK in 2018: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):120.

NICE guideline [NG121]. : Intrapartum care for women with existing medical conditions or obstetric complications and their babies [https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng121].

Beeson JG, Homer CSE, Morgan C, Menendez C. Multiple morbidities in pregnancy: time for research, innovation, and action. PLoS Med. 2018;15(9):e1002665.

Ferreira JC, Patino CM. Types of outcomes in clinical research. J Bras Pneumol. 2017;43(1):5.

Williamson PR, Altman DG, Bagley H, Barnes KL, Blazeby JM, Brookes ST, Clarke M, Gargon E, Gorst S, Harman N, et al. The COMET handbook: version 1.0. Trials. 2017;18(Suppl 3):280.

Lee SI, Eastwood K-A, Moss N, Azcoaga-Lorenzo A, Subramanian A, Anand A, Taylor B, Nelson-Piercy C, Yau C, McCowan C, et al. Protocol for the development of a core outcome set for studies of pregnant women with pre-existing multimorbidity. BMJ Open. 2021;11(10):e044919.

Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials. [https://www.comet-initiative.org/].

Keeley T, Williamson P, Callery P, Jones LL, Mathers J, Jones J, Young B, Calvert M. The use of qualitative methods to inform Delphi surveys in core outcome set development. Trials. 2016;17(1):230.

Duffy J, Thompson T, Hinton L, Salinas M, McManus RJ, Ziebland S. What outcomes should researchers select, collect and report in pre-eclampsia research? A qualitative study exploring the views of women with lived experience of pre-eclampsia. BJOG. 2019;126(5):637–46.

Viau-Lapointe J, D’Souza R, Rose L, Lapinsky SE. Development of a core outcome set for research on critically ill obstetric patients: a study protocol. Obstetric Med. 2018;11(3):132–6.

Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Chapter 9: analysis. In: Pope C, Mays N, editors. Qualitative research in Health Care. 4th ed. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell; 2020.

Berger R. Now I see it, now I don’t: researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Res. 2015;15(2):219–34.

Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M, Horey D, C OB. Evaluating maternity care: a core set of outcome measures. Birth (Berkeley Calif). 2007;34(2):164–72.

Nijagal MA, Wissig S, Stowell C, Olson E, Amer-Wahlin I, Bonsel G, Brooks A, Coleman M, Devi Karalasingam S, Duffy JMN, et al. Standardized outcome measures for pregnancy and childbirth, an ICHOM proposal. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):953.

Smith SM, Wallace E, Salisbury C, Sasseville M, Bayliss E, Fortin M. A Core Outcome Set for Multimorbidity Research (COSmm). Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(2):132–8.

Easter SR, Bateman BT, Sweeney VH, Manganaro K, Lassey SC, Gagne JJ, Robinson JN. A comorbidity-based screening tool to predict severe maternal morbidity at the time of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(3):271e271–271e210.

Salahuddin M, Mandell DJ, Lakey DL, Eppes CS, Patel DA. Maternal risk factor index and cesarean delivery among women with nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex deliveries, Texas, 2015. Birth (Berkeley Calif). 2019;46(1):182–92.

Somerville NJ, Nielsen TC, Harvey E, Easter SR, Bateman B, Diop H, Manning SE. Obstetric comorbidity and severe maternal morbidity among Massachusetts Delivery Hospitalizations, 1998–2013. Maternal & Child Health Journal. 2019;23(9):1152–8.

Bliddal M, Moller S, Vinter CA, Rubin KH, Gagne JJ, Pottegard A. Validation of a comorbidity index for use in obstetric patients: a nationwide cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(3):399–405.

Brown CC, Adams CE, George KE, Moore JE. Associations between comorbidities and severe maternal morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136(5):892–901.

Cao S, Dong F, Okekpe CC, Dombrovsky I, Valenzuela GJ, Roloff K. Prevalence of the number of pre-gestational diagnoses and trends in the United States in 2006 and 2016. J Maternal Fetal Neonatal Med 2020.

Field CP, Stuebe AM, Verbiest S, Tucker C, Ferrari R, Jonsson-Funk M. 917: early identification of women likely to be high utilizers of perinatal acute care services. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:567–S568.

Fresch R, Stephens KK, DeFranco E. 1193: the combined influence of multiple maternal medical conditions on incidence of primary cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:734–S735.

Fresch RJ, DeFranco E, Stephen K. The combined influence of maternal medical conditions on the risk of fetal growth restriction. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:154S–5.

Leonard SA, Kennedy CJ, Carmichael SL, Lyell DJ, Main EK. An expanded Obstetric Comorbidity Scoring System for Predicting severe maternal morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136(3):440–9.

Liu V, Hedderson M, Greenberg M, Kipnis P, Escobar GJ, Ruppel H. Development of an obstetrics comorbidity risk score for clinical and operational use. J Women’s Health. 2020;29:A14.

Main EK, Leonard SA, Menard MK. Association of maternal comorbidity with severe maternal morbidity: a cohort study of California mothers delivering between 1997 and 2014. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(11):11–S18.

Ranjit A, Olufajo O, Zogg C, Robinson JN, Luo G. To determine if maternal adverse outcomes predicted by obstetric comorbidity index (OBCMI) varies according to race. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:37S–8.

Salahuddin M, Mandell DJ, Lakey DL, Ramsey PS, Eppes CS, Davidson CM, Ortique CF, Patel DA. Maternal comorbidity index and severe maternal morbidity during delivery hospitalizations in Texas, 2011–2014. Birth (Berkeley Calif). 2020;47(1):89–97.

Sutton D, Oberhardt M, Oxford-Horrey CM, Prabhu M, aubey J, Riley LE, D’Alton ME, Goffman D. 711 obstetric comorbidity index corresponds with racial disparity in maternal morbidity providing insight for risk reduction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:445–S446.

Clapp MA, James KE, Kaimal AJ. The effect of hospital acuity on severe maternal morbidity in high-risk patients. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 2018, 219(1):111.e111-111.e117.

Metcalfe A, Wick J, Ronksley P. Racial disparities in comorbidity and severe maternal morbidity/mortality in the United States: an analysis of temporal trends. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97(1):89–96.

Aoyama K, D’Souza R, Inada E, Lapinsky SE, Fowler RA. Measurement properties of comorbidity indices in maternal health research: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth. 2017;17(1):372.

Cunningham SD, Herrera C, Udo IE, Kozhimannil KB, Barrette E, Magriples U, Ickovics JR. Maternal medical complexity: impact on prenatal Health Care spending among women at low risk for Cesarean Section. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(5):551–8.

Hehir MP, Ananth CV, Wright JD, Siddiq Z, D’Alton ME, Friedman AM. Severe maternal morbidity and comorbid risk in hospitals performing < 1000 deliveries per year. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 2017, 216(2):179.e171-179.e112.

Oberhardt M, Sutton D, Oxford-Horrey C, Prabhu M, Sheen JJ, Riley L, D’Alton M, Goffman D. 8 augmenting or replacing Obstetric Comorbidity Index with Labor & Delivery features improves prediction of Non-Transfusion severe maternal morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:5.

Bateman BT, Mhyre JM, Hernandez-Diaz S, Huybrechts KF, Fischer MA, Creanga AA, Callaghan WM, Gagne JJ. Development of a comorbidity index for use in obstetric patients. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):957–65.

Metcalfe A, Lix L, Johnson J-A, Currie G, Lyon A, Bernier F, Tough S. Validation of an obstetric comorbidity index in an external population. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2015;122(13):1748–55.

Knight M, Bunch K, Tuffnell D, Shakespeare J, Kotnis R, Kenyon S, Kurinczuk JJ, editors. On behalf of MBRRACE-UK: saving lives, improving mothers’ care - Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into maternal deaths and morbidity 2016-18. In. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford; 2020.

Subramanian A, Azcoaga- Lorenzo A, Phillips K, Lee SI, Anand A, Fagbamigbe AF, Damase-Michel C, McCowan C, O’Reilly D, Hope H et al. Trends in the prevalence of polypharmacy during pregnancy in the UK 2000–2019. In: BJOG vol. 129; 2022: 111–112.

Admiraal LAC, Rosman AN, Dolhain RJEM, West RL, Mulders AGMGJ. Facilitators and barriers of preconception care in women with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatic diseases: an explorative survey study in a secondary and tertiary hospital. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):238.

Ackerman IN, Jordan JE, Van Doornum S, Ricardo M, Briggs AM. Understanding the information needs of women with rheumatoid arthritis concerning pregnancy, post-natal care and early parenting: a mixed-methods study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:194.

“Walking into the unknown… key challenges of pregnancy and early parenting with inflammatory arthritis: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Arthritis Research & Therapy 2021, 23(1):123.

Williams A-J, Karimi N, Chari R, Connor S, De Vera MA, Dieleman LA, Hansen T, Ismond K, Khurana R, Kingston D, et al. Shared decision making in pregnancy in inflammatory bowel disease: design of a patient orientated decision aid. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21(1):302.

Flanagan EK, Richmond J, Thompson AJ, Desmond PV, Bell SJ. Addressing pregnancy-related concerns in women with inflammatory bowel disease: insights from the patient’s perspective. JGH open: an open access journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2021;5(1):28–33.

Joung WJ. Pregnancy and childbirth experiences of women with Epilepsy: a Phenomenological Approach. Asian Nurs Res. 2019;13(2):122–9.

Lynch MM, Squiers LB, Kosa KM, Dolina S, Read JG, Broussard CS, Frey MT, Polen KN, Lind JN, Gilboa SM, et al. Making decisions about medication use during pregnancy: implications for communication strategies. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(1):92–100.

Brown HK, Qazilbash A, Rahim N, Dennis C-L, Vigod SN. Chronic Medical Conditions and Peripartum Mental illness: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(9):2060–8.

Jones JE, Jones LL, Keeley TJ, Calvert MJ, Mathers J. A review of patient and carer participation and the use of qualitative research in the development of core outcome sets. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(3):e0172937.

Alkhaffaf B, Blazeby JM, Bruce IA, Morris RL. Patient priorities in relation to surgery for gastric cancer: qualitative interviews with gastric cancer surgery patients to inform the development of a core outcome set. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2):e034782.

Carroll JH, Martin-McGill KJ, Cross JH, Hickson M, Williams E, Aldridge V, Collinson A. Core outcome set development for childhood epilepsy treated with ketogenic diet therapy: results of a scoping review and parent interviews. Seizure. 2022;99:54–67.

Gonçalves A-C, Marques A, Samuel D, Demain S. Outcomes of physical activity for people living with dementia: qualitative study to inform a Core Outcome Set. Physiotherapy. 2020;108:129–39.

Quirke F, Ariff S, Battin M, Bernard C, Bloomfield FH, Daly M, Devane D, Haas DM, Healy P, Hurley T, et al. Core outcomes in neonatal encephalopathy: a qualitative study with parents. BMJ Paediatrics Open. 2022;6(1):e001550.

Hall C, D’Souza RD. Patients and Health Care Providers identify important outcomes for research on pregnancy and heart disease. CJC Open. 2020;2(6):454–61.

Kaufman J, Ryan R, Hill S. Qualitative focus groups with stakeholders identify new potential outcomes related to vaccination communication. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8):e0201145.

Smith V, Daly D, Lundgren I, Eri T, Benstoem C, Devane D. Salutogenically focused outcomes in systematic reviews of intrapartum interventions: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Midwifery. 2014;30(4):e151–156.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following organisations for helping with recruitment for the focus groups: 4 M Project, Beat (Eating Disorders), British Thyroid Foundation, Bump2Baby Parent and Public Involvement Group (Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit), Caribbean Nurses and Midwives Association (UK), Crohn’s and Colitis UK, Diabetes UK (forum), Elly Charity, Epilepsy Action, General Practitioners Championing Perinatal Care, Health and Care Research Wales, Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia Support for UK HSP’rs, Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, Katie’s Team, Kidney Patient Involvement Network, Kidney Research UK, Multiple Sclerosis Society UK, Mums Like Us, National Childbirth Trust, National Kidney Federation, Perinatal Mental Health Research (Facebook), Polycystic Kidney Disease Charity, Positive Birth Edinburgh, Positive Birth Scotland: Hypnobirthing and Birth Preparation, Psoriasis Association, Raham Project, Rare Autoinflammatory Conditions Community – UK, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Women’s Voices Involvement Panel, West Bromwich African Caribbean Resource Centre, Somerville Heart Foundation, The Birth and Baby Space (Facebook), The Migraine Trust, The Voice for Epilepsy, The Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia Support Group, Versus Arthritis, Women Connect First.

Funding

This work was funded by the Strategic Priority Fund “Tackling multimorbidity at scale” programme (grant number MR/W014432/1) delivered by the Medical Research Council and the National Institute for Health Research in partnership with the Economic and Social Research Council and in collaboration with the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. BT was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) West Midlands Applied Research Collaboration. The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the funders, the NIHR or the UK Department of Health and Social Care. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SIL: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review and editing, Project administration. SH: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - review and editing.ZV: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing - review and editing, Funding acquisition. RP: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Resources, Formal analysis, Writing - review and editing, Funding acquisition. AAL, CNP, CM, DOR, KMA, KAE, NM, SB: Conceptualisation, Resources, Writing - review and editing, Funding acquisition. BT, LL, HH: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Writing - review and editing, Funding acquisition. MS: Project administration, Writing - review and editing. KN: Conceptualisation, Resources, Writing - review and editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. ST: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Resources, Writing - review and editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. MB: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Resources, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing -review and editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has received ethical approval from the University of Birmingham Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics Ethical Review Committee (ERN_20-1264) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. An electronic copy of the consent form was email to participants, a signed copy was emailed back to the research team. Informed written and verbal consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable as no identifying information is included in this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, S.I., Hanley, S., Vowles, Z. et al. Key outcomes for reporting in studies of pregnant women with multiple long-term conditions: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23, 551 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05773-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05773-5